#writing tip

Text

WRITING TIP:

Actually write. Don't plagiarize or steal from writers.

#writing tips#writing tip#writerblr#anti ai#generative ai#fuck ai everything#writers on tumblr#this is my career and if i lose it i will personally make sure those most responsible lose everything also#idc. writing is my life's work. you should be ashamed of yourself

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

#let’s write#writing tips#writing help#writing tips and tricks#writing tip#writer#writeblr#fanfic#writing

7K notes

·

View notes

Note

I don't know if you've done this before but what are some good ways to describe speech?

Ways to Describe Speech

-> feel free to edit and adjust pronouns as you see fit.

His voice was deep like the rumbling of the earth.

She had the voice of a singer, smooth and rich like chocolate.

Their voice reminded him of spring rain.

He often paused in his speaking, like a car radio that had lost signal.

She had a lilt to her voice that made it seem like she was asking a question.

Their voice was monotonous, threatening to put her to sleep with every word.

He couldn't put her voice into words. It was... otherworldly.

Her voice was brittle, as if she were on the verge of tears.

Their voice was authoritative. Their words carried like a loud command.

His voice, unapologetic and unwavering, made her shrink back.

Her voice was barely above a whisper.

Their words were cold with anger.

Other Words to Use to Describe Voice:

Firm

Formal

Frank

Hesitant

Humorous

Passionate

Playful

Professional

Respectful

Serious

Sympathetic

Smug

Superior

Croaky

Dry

Forceful

Grating

Hateful

Insincere

Nasally

Snarky

Tuneless

Wavering

Breaking

Coarse

Flat

Hoarse

High Pitched

Husky

Mellow

Raspy

Rough

Scratchy

Strong

Trembling

Boisterous

Booming

Screeching

Faint

Feeble

Frail

Penetrating

Piercing

Quiet

Raised

Shrill

Soft

Weak

Whisper

Captivating

Deep

Feathery

Hypnotic

Lilting

Mesmerizing

Rich

Smoky

Soothing

Breathy

Delicate

Warbling

If you like what I do and want to support me, please consider donating! I also offer editing services and other writing advice on my Ko-fi!

#writing prompts#creative writing#writeblr#prompt list#ask box prompts#how to describe speech#how to describe voice#how to write#writing help#writing inspiration#writing tip#writing ideas

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

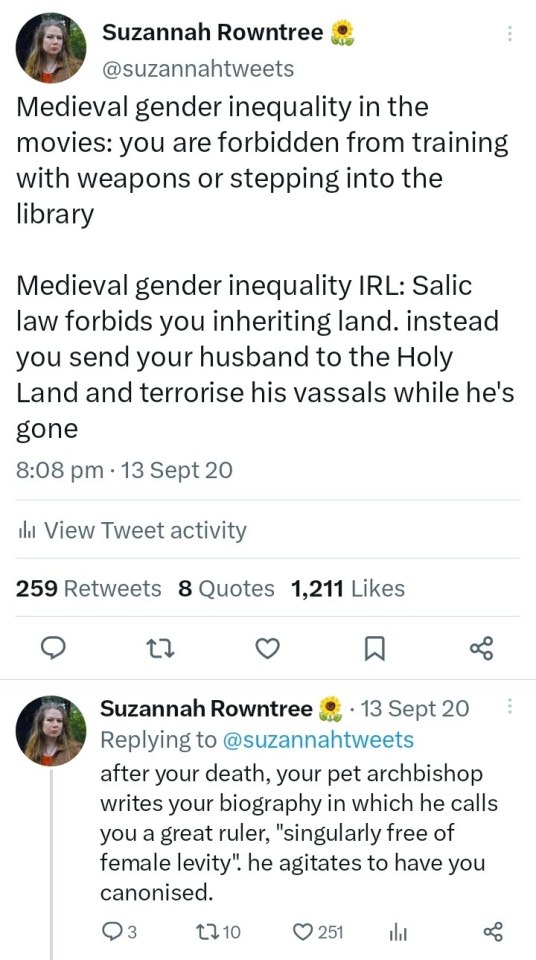

all RIGHT:

Why You're Writing Medieval (and Medieval-Coded) Women Wrong: A RANT

(Or, For the Love of God, People, Stop Pretending Victorian Style Gender Roles Applied to All of History)

This is a problem I see alllll over the place - I'll be reading a medieval-coded book and the women will be told they aren't allowed to fight or learn or work, that they are only supposed to get married, keep house and have babies, &c &c.

If I point this out ppl will be like "yes but there was misogyny back then! women were treated terribly!" and OK. Stop right there.

By & large, what we as a culture think of as misogyny & patriarchy is the expression prevalent in Victorian times - not medieval. (And NO, this is not me blaming Victorians for their theme park version of "medieval history". This is me blaming 21st century people for being ignorant & refusing to do their homework).

Yes, there was misogyny in medieval times, but 1) in many ways it was actually markedly less severe than Victorian misogyny, tyvm - and 2) it was of a quite different type. (Disclaimer: I am speaking specifically of Frankish, Western European medieval women rather than those in other parts of the world. This applies to a lesser extent in Byzantium and I am still learning about women in the medieval Islamic world.)

So, here are the 2 vital things to remember about women when writing medieval or medieval-coded societies

FIRST. Where in Victorian times the primary axes of prejudice were gender and race - so that a male labourer had more rights than a female of the higher classes, and a middle class white man would be treated with more respect than an African or Indian dignitary - In medieval times, the primary axis of prejudice was, overwhelmingly, class. Thus, Frankish crusader knights arguably felt more solidarity with their Muslim opponents of knightly status, than they did their own peasants. Faith and age were also medieval axes of prejudice - children and young people were exploited ruthlessly, sent into war or marriage at 15 (boys) or 12 (girls). Gender was less important.

What this meant was that a medieval woman could expect - indeed demand - to be treated more or less the same way the men of her class were. Where no ancient legal obstacle existed, such as Salic law, a king's daughter could and did expect to rule, even after marriage.

Women of the knightly class could & did arm & fight - something that required a MASSIVE outlay of money, which was obviously at their discretion & disposal. See: Sichelgaita, Isabel de Conches, the unnamed women fighting in armour as knights during the Third Crusade, as recorded by Muslim chroniclers.

Tolkien's Eowyn is a great example of this medieval attitude to class trumping race: complaining that she's being told not to fight, she stresses her class: "I am of the house of Eorl & not a serving woman". She claims her rights, not as a woman, but as a member of the warrior class and the ruling family. Similarly in Renaissance Venice a doge protested the practice which saw 80% of noble women locked into convents for life: if these had been men they would have been "born to command & govern the world". Their class ought to have exempted them from discrimination on the basis of sex.

So, tip #1 for writing medieval women: remember that their class always outweighed their gender. They might be subordinate to the men within their own class, but not to those below.

SECOND. Whereas Victorians saw women's highest calling as marriage & children - the "angel in the house" ennobling & improving their men on a spiritual but rarely practical level - Medievals by contrast prized virginity/celibacy above marriage, seeing it as a way for women to transcend their sex. Often as nuns, saints, mystics; sometimes as warriors, queens, & ladies; always as businesswomen & merchants, women could & did forge their own paths in life

When Elizabeth I claimed to have "the heart & stomach of a king" & adopted the persona of the virgin queen, this was the norm she appealed to. Women could do things; they just had to prove they were Not Like Other Girls. By Elizabeth's time things were already changing: it was the Reformation that switched the ideal to marriage, & the Enlightenment that divorced femininity from reason, aggression & public life.

For more on this topic, read Katherine Hager's article "Endowed With Manly Courage: Medieval Perceptions of Women in Combat" on women who transcended gender to occupy a liminal space as warrior/virgin/saint.

So, tip #2: remember that for medieval women, wife and mother wasn't the ideal, virgin saint was the ideal. By proving yourself "not like other girls" you could gain significant autonomy & freedom.

Finally a bonus tip: if writing about medieval women, be sure to read writing on women's issues from the time so as to understand the terms in which these women spoke about & defended their ambitions. Start with Christine de Pisan.

I learned all this doing the reading for WATCHERS OF OUTREMER, my series of historical fantasy novels set in the medieval crusader states, which were dominated by strong medieval women! Book 5, THE HOUSE OF MOURNING (forthcoming 2023) will focus, to a greater extent than any other novel I've ever yet read or written, on the experience of women during the crusades - as warriors, captives, and political leaders. I can't wait to share it with you all!

#watchers of outremer#medieval history#the lady of kingdoms#the house of mourning#writing#writing fantasy#female characters#medieval women#eowyn#the lord of the rings#lotr#history#historical fiction#fantasy#writing tip#writing advice

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

“the opening sentence of a fic is one of the most important parts, since it tells readers the tone, the setting and the writing style of the entire fic”

me trying not to be nervous as I write the opening sentence of my fic:

#writing#writer#writeblr#ao3#archive of our own#whump#writing challenge#writing memes#ao3 memes#ao3 meme#writing advice#writing tip#writing tips#whumpblr#angst#writing inspo#writing inspiration#meme#memes#writing community#whump community#whump blog#writing tropes#tropes#trope#whump tropes#writing trope#whump trope#prompt#prompts

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

50 WORDS TO USE INSTEAD OF “SAID”

Do you ever find yourself over-using the word “said” in your writing? Try using these words/phrases instead:

stated

commented

declared

spoke

responded

voiced

noted

uttered

iterated

explained

remarked

acknowledged

mentioned

announced

shouted

expressed

articulated

exclaimed

proclaimed

whispered

babbled

observed

deadpanned

joked

hinted

informed

coaxed

offered

cried

affirmed

vocalized

laughed

ordered

suggested

admitted

verbalized

indicated

confirmed

apologized

muttered

proposed

chatted

lied

rambled

talked

pointed out

blurted out

chimed in

brought up

wondered aloud

(NOTE: Keep in mind that all of these words have slightly different meanings and are associated with different emotions/scenarios.)

#words to use instead of#said#words#writing prompt#prompt#writing#prompts#writing prompts#creative writing#writing advice#verbs#verb#word#synonym#synonyms#writing tip#writing tips#writing help#word choice#writer

62K notes

·

View notes

Text

What to give a fuck about,while writing your first draft!

I`ve posted a list about things you don´t need to give a fuck about while writing your first draft. Here are things you NEED TO CARE about! (in my opinion)

Your Authentic Voice: Don't let the fear of judgment or comparison stifle your unique voice. I know it´s hard,but try to write from your heart, and don't worry about perfection in the first draft. Let your authenticity shine through your words.

Your Story, Your Way: It's your narrative, your world, and your characters. Don't let external expectations or trends dictate how your story should unfold. Write the story you want to tell.

Progress Over Perfection: Your first draft is not the final product; it's the raw material for your masterpiece. Give a fuck about making progress, not achieving perfection. Embrace imperfections and understand that editing comes later.

Consistency and Routine: Discipline matters. Make a commitment to your writing routine and stick to it.

Feedback and Growth: While it's essential to protect your creative space during the first draft, be open to constructive feedback later on. Giving a f*ck about growth means you're willing to learn from others and improve your work.

Self-Compassion: Mistakes, writer's block, and self-doubt are all part of the process. Give a f*ck about being kind to yourself. Don't beat yourself up if the words don't flow perfectly every time. Keep pushing forward and remember that writing is a journey.

Remember, the first draft is your canvas, your playground. Don't bog yourself down with unnecessary worries.

#writing#writblr#writing advice#writers block#just writer things#creative writing#fanfiction writing#writing motivation#writeblr#original writing#writing reference#writing tips#writers on tumblr#writing resources#writing tip#writing encouragement#writing community#writers#world building#point of view#editing#character creation#dialogue#mine.#words#writingtips#writingadvice

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Encouragment for writers that I know seems discouraging at first but I promise it’s motivational-

• Those emotional scenes you’ve planned will never be as good on page as they are in your head. To YOU. Your audience, however, is eating it up. Just because you can’t articulate the emotion of a scene to your satisfaction doesn’t mean it’s not impacting the reader.

• Sometimes a sentence, a paragraph, or even a whole scene will not be salvagable. Either it wasn’t necessary to the story to begin with, or you can put it to the side and re-write it later, but for now it’s gotta go. It doesn’t make you a bad writer to have to trim, it makes you a good writer to know to trim.

• There are several stories just like yours. And that’s okay, there’s no story in existence of completely original concepts. What makes your story “original” is that it’s yours. No one else can write your story the way you can.

• You have writing weaknesses. Everyone does. But don’t accept your writing weaknesses as unchanging facts about yourself. Don’t be content with being crap at description, dialogue, world building, etc. Writers that are comfortable being crap at things won’t improve, and that’s not you. It’s going to burn, but work that muscle. I promise you’ll like the outcome.

#hope that helps!#writers on tumblr#writing help#writing advice#writing tumblr#writer tips#writing blog#writing tips#writing tip#writblr#writing#fanfic writers#writeblr#writer blog#writers of tumblr#ya novels#fanfiction#original fiction

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

Pro Tip: The Way You End a Sentence Matters

Here is a quick and dirty writing tip that will strengthen your writing.

In English, the word at the end of a sentence carries more weight or emphasis than the rest of the sentence. You can use that to your advantage in modifying tone.

Consider:

In the end, what you said didn't matter.

It didn't matter what you said in the end.

In the end, it didn't matter what you said.

Do you pick up the subtle differences in meaning between these three sentences?

The first one feels a little angry, doesn't it? And the third one feels a little softer? There's a gulf of meaning between "what you said didn't matter" (it's not important!) and "it didn't matter what you said" (the end result would've never changed).

Let's try it again:

When her mother died, she couldn't even cry.

She couldn't even cry when her mother died.

That first example seems to kind of side with her, right? Whereas the second example seems to hold a little bit of judgment or accusation? The first phrase kind of seems to suggest that she was so sad she couldn't cry, whereas the second kind of seems to suggest that she's not sad and that's the problem.

The effect is super subtle and very hard to put into words, but you'll feel it when you're reading something. Changing up the order of your sentences to shift the focus can have a huge effect on tone even when the exact same words are used.

In linguistics, this is referred to as "end focus," and it's a nightmare for ESL students because it's so subtle and hard to explain. But a lot goes into it, and it's a tool worth keeping in your pocket if you're a creative writer or someone otherwise trying to create a specific effect with your words :)

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

how to write fight scenes

many people have told me that Chum has good fight scenes. a small subset of those people have asked me on advice for how to write fight scenes. i am busy procrastinating, so i have distilled my general ethos on fight scenes into four important points. followed by a homework assignment.

Fight scenes take place on two axii - the physical and the intellectual. For the most interesting fight scenes, neither character should have a full inventory of the other's abilities, equipment, fighting style, etc. This gives you an opportunity to pull out surprises, but, more importantly, turns each fight into a jockeying of minds, as all characters involved have to puzzle out what's going on in real time. This is especially pertinent for settings with power systems. It feels more earned if the characters are trying to deduce the limitations and reach of the opponent's power rather than the opponent simply explaining it to them (like in Bleach. Don't do that).

1a. Have characters be incorrect in their assumptions sometimes, leading to them making mistakes that require them to correct their internal models of an opponent under extreme pressure.

1b. If you really have to have a character explain their powers to someone there should be a damn good reason for it. The best reason is "they are lying". The second best reason is "their power requires it for some reason".

Make sure your blows actually have weight. When characters are wailing at each other for paragraphs and paragraphs and nothing happens, it feels like watching rock 'em sock 'em robots. They beat each other up, and then the fight ends with a decisive blow. Not interesting! Each character has goals that will influence what their victory condition is, and each character has a physical body that takes damage over the course of a fight. If someone is punched in the gut and coughs up blood, that's an injury! It should have an impact on them not just for the fight but long term. Fights that go longer than "fist meets head, head meets floor" typically have a 'break-down' - each character getting sloppier and weaker as they bruise, batter, and break their opponent, until victory is achieved with the last person standing. this keeps things tense and interesting.

I like to actually plan out my fight scenes beat for beat and blow for blow, including a: the thought process of each character leading to that attempted action, b: what they are trying to do, and c: how it succeeds or fails. In fights with more than two people, I like to use graph paper (or an Excel spreadsheet with the rows turned into squares) to keep track of positions and facings over time.

Don't be afraid to give your characters limitations, because that means they can be discovered by the other character and preyed upon, which produces interesting ebbs and flows in the fight. A gunslinger is considerably less useful in a melee with their gun disarmed. A swordsman might not know how to box if their sword is destroyed. If they have powers, consider what they have to do to make them activate, if it exhausts them to use, how they can be turned off, if at all. Consider the practical applications. Example: In Chum, there are many individuals with pyrokinetic superpowers, and none of them have "think something on fire" superpowers. Small-time filler villain Aaron McKinley can ignite anything he's looking at, and suddenly the fight scenes begin constructing themselves, as Aaron's eyes and the direction of his gaze become an incredibly relevant factor.

if you have reached this far in this essay I am giving you homework. Go watch the hallway fight in Oldboy and then novelize it. Then, watch it again every week for the rest of your life, and you will become good at writing fight scenes.

as with all pieces of advice these are not hard and fast rules (except watching the oldboy hallway fight repeatedly) but general guidelines to be considered and then broken when it would produce an interesting outcome to do so.

okay have a good day. and go read chum.

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

How do I describe a character when they’re angry and just “so done”? How would they act?

A Quick Guide to Writing Anger

It’s the hot-blooded, ever-challenging, angry character that often steals a scene and captivates readers’ hearts. From the brooding protagonist to the volatile villain, anger introduces a heightened element of emotive dynamism. Anger is a powerful emotion that can define a character's behaviour, interactions, body language, and attitude.

How Do They Behave?

Make impulsive decisions

Have a short fuse and react explosively

Hold grudges

Be physically aggressive

Be motivated by revenge

Exhibit self-destructive tendencies

Speak at an increased volume

Speak unexpectedly fast or slow

How Do They Interact?

Have issues with authority

Struggle to follow orders or instructions

Confrontational or verbally abusive

Overuse of swear words or insults

Struggle to focus or listen to others

Dominate conversations and interrupt often

Become isolationist

Short-tempered and accusatory

Describe Their Body Language

Clenched fists and tight jaw

Rigid and defensive posture

Maintained eye contact

Pacing or fidgeting

Aggressive movements

Increased muscle tension

Point and jab when speaking

Invade others’ personal space

Describe Their Attitude

A sense of dissatisfaction and frustration

Overly sceptical and distrustful of others

Impatient and easily annoyed

Confrontational and arrogant

Feelings of powerlessness

Motivated by vengeance or justice

Hostile and irritable

Blunt, direct, and stubborn

A lack of empathy

Positive Outcomes

Be a motivator for change

Inspire others with their passion for justice

Can be a motivator for personal growth

Learn to articulate their needs and set boundaries

Develop resilience and strength by managing their anger

Increased assertiveness

Experience catharsis and emotional release

Improved problem-solving skills

Negative Outcomes

Damaging to their relationship with others

Can lead to chronic stress or health issues

Become isolated, leading to loneliness and depression

Develop a reputation for being difficult or aggressive

Can cause legal troubles or social rejection

Lower self-esteem and sense of self-worth

Become violent or cause physical harm

Exhibit impaired judgement or decision-making

Useful synonyms

Furious

Enraged

Wrathful

Incensed

Infuriated

Livid

Raging

Fuming

Irate

Outraged

Vexed

Irritated

Resentful

Indignant

Seething

Mad

Hostile

Incensed

Cross

Huffy

#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writeblr#writerblr#writing inspiration#writing tips#writblr#writing anger#writers corner#writing advice#writing resources#writing characters#writing tips and tricks#how to write#writing tip#writing help#creative writing resources#writer resources#let's write#learn to write#writing quick tips#character reference#character development

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Do Your Research

This phrase is regularly thrown around writeblr and for good reason. It's important to research what you are writing about to know what to include, what can be fudged, and how to depict whatever you're writing. I see "do your research" most thrown around by well-meaning and highly traditionally educated writers. It's solid advice, after all!

But how do you research?

For those writers who don't already have the research skills necessary to write something comfortably already downloaded into your brain, I put this guide together for you.

Where do I even start?

It's a daunting task, research. But the best place to start is with the most basic, stupidest question you can think of. I'm going to talk about something that I already know a lot about: fighting.

When researching fight scenes, a great way to start is to look up what different weapons are. There are tons out there! So ask the stupid questions. What is a sword? What is a gun? How heavy are they?

Google and Wikipedia can help you a lot with these basic-level questions. They aren't great sources for academic articles, but remember, this is fiction. It doesn't need to be perfect, and it doesn't need to be 100% accurate if you don't want it to be. But knowing what is true to life will help you write well. Just like knowing the rules of writing will help you break them.

You may find in your basic research sweep that you have a lot more specific questions. Write them all down. It doesn't matter if they seem obvious. Write them down because they will be useful later.

How To Use Wikipedia Correctly

Wikipedia is a testament to cooperative human knowledge. It's also easy to edit by anonymous users, which means there is a lot of room for inaccuracies and misleading information. Wikipedia is usually pretty good about flagging when a source is needed or when misleading language is obvious, but Wikipedia itself isn't always the most accurate or in-depth source.

Wikipedia is, however, an excellent collection of sources. When I'm researching a subject that I know nothing about, say Norse mythology, a good starting point is the Wikipedia page for Odin. You'll get a little background on Odin's name and Germanic roots, a little backstory on some of the stories, where they appear, and how they are told.

When you read one of the sentences, and it sparks a new question, write the question down, and then click on the superscript number. This will take you directly to the linked source for the stated fact. Click through to that source. Now you have the source where the claim was made. This source may not be a primary source, but a secondary source can still lead you to new discoveries and details that will help you.

By "source-hopping," you can find your way across the internet to different pieces of information more reliably. This information may repeat itself, but you will also find new sources and new avenues of information that can be just as useful.

You mean I don't need a library?

Use your library. Libraries in many parts of the US are free to join, and they have a wealth of information that can be easily downloaded online or accessed via hardcopy books.

You don't, however, need to read every source in the library for any given topic, and you certainly don't need to read the whole book. Academic books are different from fiction. Often their chapters are divided by topic and concept and not by chronological events like a history textbook.

For example, one of my favorite academic books about legislative policy and how policy is passed in the US, by John Kingdon, discusses multiple concepts. These concepts build off one another, but ultimately if you want to know about one specific concept, you can skip to that chapter. This is common in sociological academic books as well.

Going off of my Norse Mythology example in the last section, a book detailing the Norse deities and the stories connected to them will include chapters on each member of the major pantheon. But if I only care about Odin, I can focus on just the chapters about Odin.

Academic Articles and How To Read Them

I know you all know how to read. But learning how to read academic articles and books is a skill unto itself. It's one I didn't quite fully grasp until grad school. Learn to skim. When looking at articles published in journals that include original research, they tend to follow a set structure, and the order in which you read them is not obvious. At all.

Start with the abstract. This is a summary of the paper that will include, in about half a page to a page, the research question, hypothesis, methods/analysis, and conclusions. This abstract will help you determine if the answer to your question is even in this article. Are they asking the right question?

Next, read the research question and hypothesis. The hypothesis will include details about the theory and why the researcher thinks what they think. The literature review will go into much more depth about theories, what other people have done and said, and how that ties into the research of the present article. You don't need to read that just yet.

Skim the methods and analysis section. Look at every data table and graph included and try to find patterns yourself. You don't need to read every word of this section, especially if you don't understand a lot of the words and jargon used. Some key points to consider are: qualitative vs. quantitative data, sample size, confounding factors, and results.

(Some definitions for those of you who are unfamiliar with these terms. Qualitative data is data that cannot be quantified into a number. These are usually stories and anecdotes. Quantitative data is data that can be transferred into a numerical representation. You can't graph qualitative data (directly), but you can graph quantitative data. Sample size is the number of people or things counted (n when used in academic articles). Your sample size can indicate how generalizable your conclusions are. So pay attention. Did the author interview 300 subjects? Or 30? There will be a difference. A confounding factor is a factor that may affect the working theory. An example of a theory would be "increasing LGBTQ resources in a neighborhood would decrease LGBTQ hate crimes in that area." A confounding factor would be "increased reporting of hate crimes in the area." The theory, including the confounding factor, would look like "increasing LGBTQ resources in a neighborhood would increase the reporting of hate crimes in the area, which increases the number of hate crimes measured in that area." The confounding factor changes the outcome because it is a factor not considered in the original theory. When looking at research, see if you can think of anything that may change the theory based on how that factor interacts with the broader concept. Finally, the results are different from the conclusions. The results tell you what the methods spit out. Analysis tells you what the results say, and conclusions tell you what generalizations can be made based on the analysis.)

Next, read the conclusion section. This section will tell you what general conclusions can be made from the information found in the paper. This will tell you what the author found in their research.

Finally, once you've done all that, go back to the literature review section. You don't have to read it necessarily, but reading it will give you an idea of what is in each sourced paper. Take note of the authors and papers sourced in the literature review and repeat the process on those papers. You will get a wide variety of expert opinions on whatever concept or niche you're researching.

Starting to notice a pattern?

My research methods may not necessarily work for everybody, but they are pretty standard practice. You may notice that throughout this guide, I've told you to "source-hop" or follow the sources cited in whatever source you find first. This is incredibly important. You need to know who people are citing when they make claims.

This guide focused on secondary sources for most of the guide. Primary sources are slightly different. Primary sources require understanding the person who created the source, who they were, and their motivations. You also may need to do a little digging into what certain words or phrases meant at the time it was written based on what you are researching. The Prose Edda, for example, is a telling of the Norse mythology stories written by an Icelandic historian in the 13th century. If you do not speak the language spoken in Iceland in 1232, you probably won't be able to read anything close to the original document. In fact, the document was lost for about 300 years. Now there are translations, and those translations are as close to the primary source you can get on Norse Mythology. But even then, you are reading through several veils of translation. Take these things into account when analyzing primary documents.

Research Takes Practice

You won't get everything you need to know immediately. And researching subjects you have no background knowledge of can be daunting, confusing, and frustrating. It takes practice. I learned how to research through higher formal education. But you don't need a degree to write, so why should you need a degree to collect information? I genuinely hope this guide helps others peel away some of the confusion and frustration so they can collect knowledge as voraciously as I do.

– Indy

#writing advice#writing tips#writing resources#writeblr#amwriting#writblr#writers of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writing help#writing guide#how to research#reading research articles#do some research#do your own research#do your research#research for writers#writing research#writing tip#writing reference#writer tips

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

8K notes

·

View notes

Note

How to write about someone’s appearance? Their physique, styles, face , clothes,?

How to Describe a Character's Appearance

-> dabblewriter.com

-> link to Character Description Prompts

Avoid Over-Describing

Overloading readers with too much information can be overwhelming and make your characters feel flat and one-dimensional. Focus on the details that are the most important to the story and the characters themselves.

If the character's appearance is not central to the story, then you may only need to give a basic description. If it plays a significant role, you may want to go into more detail. Always keep the purpose of your physical descriptions in mind.

Show Don't Tell

Don't blatantly state every little thing about your character's appearance, but rather show it through their actions and behaviors.

example: If they are tall, show that through their actions. They have to duck to get under a doorway, they help someone reach the top shelf, etc.

Include Personality Traits

A character's personality is what makes them memorable. Consider their motivations, values, beliefs, and quirks and give them a well-defined personality.

Avoid Stereotypes

Create characters that are more than just their cultural, racial, ethnic, or gender identity. Give them unique interests, hobbies, and personalities. Allow them to have flaws, contradictions, and diverse perspectives.

External Features

External features include a character's height, weight, body type, and general appearance. You can describe their skin color, hair color, eye color, and any distinctive features like freckles or scars. This type of description gives the reader a basic understanding of what the character looks like, which is helpful in creating a mental image.

Clothing

Describing the type of clothing they wear, including the colors, patterns, and how they fit, can reveal a lot about a character’s personality and social status.

For example, a character who wears tailored suits and expensive shoes might be a little snobby and concerned with their image, while a character who wears ripped jeans and t-shirts might be casual and relaxed.

Facial Features

Facial features can be used to give the reader a more in-depth understanding of a character's personality and emotions. You can describe their smile, the way they frown, their cheekbones, and their jawline. You can also describe their eyebrows, the shape of their nose, and the size and shape of their eyes, which can give the reader insight into their emotions.

Body Language

Body language can be used to give the reader an understanding of a character's emotions and personality without the need for dialogue. Describing the way a character stands, walks, or gestures can reveal a lot about their confidence level, mood, and attitude.

For example, a character who slouches and avoids eye contact is likely to be shy, while a character who stands up straight and makes direct eye contact is likely to be confident.

Words to Describe Various Features

Head and face

Oval: rounded, elongated, balanced, symmetrical

Round: full, plump, chubby, cherubic

Square: angular, defined, strong, masculine

Heart: pointy, triangular, wider at the temples, narrow at the chin

Diamond: angular, pointed, narrow at the forehead and jaw, wide at the cheekbones

Long: elongated, narrow, oval, rectangular

Triangular: angular, wide at the jaw, narrow at the forehead, inverted heart-shape

Oblong: elongated, rectangular, similar to oval but longer

Pear-shaped: narrow at the forehead, wide at the jaw and cheekbones, downward-pointing triangle

Rectangular: angular, defined, similar to oblong but more squared

Facial features

Cheeks: rosy, plump, gaunt, sunken, dimpled, flushed, pale, chubby, hollow

Chin: pointed, cleft, rounded, prominent, dimpled, double, weak, strong, square

Ear: large, small, delicate, flapped, pointed, rounded, lobeless, pierced

Eyes: deep-set, angled, bright, piercing, hooded, wide-set, close-set, beady, slanted, round, droopy, sleepy, sparkling

Forehead: high, broad, wrinkled, smooth, furrowed, low, narrow, receding

Jaw: strong, square, defined, angular, jutting, soft, weak, chiseled

Lips: full, thin, chapped, cracked, puckered, pursed, smiling, quivering, pouty

Mouth: wide, small, downturned, upturned, smiling, frowning, pouting, grimacing

Nose: hooked, straight, aquiline, button, long, short, broad, narrow, upturned, downturned, hooked, snub

Eyebrows: arched, bushy, thin, unkempt, groomed, straight, curved, knitted, furrowed, raised

Hair

Texture: curly, straight, wavy, frizzy, lank, greasy, voluminous, luxurious, tangled, silky, coarse, kinky

Length: long, short, shoulder-length, waist-length, neck-length, chin-length, buzzed, shaven

Style: styled, unkempt, messy, wild, sleek, smoothed, braided, ponytail, bun, dreadlocks

Color: blonde, brunette, red, black, gray, silver, salt-and-pepper, auburn, chestnut, golden, caramel

Volume: thick, thin, fine, full, limp, voluminous, sparse

Parting: center-parted, side-parted, combed, brushed, gelled, slicked back

Bangs: fringed, side-swept, blunt, wispy, thick, thin

Accessories: headband, scarf, barrettes, clips, pins, extensions, braids, ribbons, beads, feathers

Body

Build: slender, skinny, lean, athletic, toned, muscular, burly, stocky, rotund, plump, hefty, portly

Height: tall, short, petite, lanky, willowy, stocky, rotund

Posture: slouching, upright, hunched, stiff, relaxed, confident, nervous, slumped

Shape: hourglass, pear-shaped, apple-shaped, athletic, bulky, willowy, curvy

Muscles: defined, toned, prominent, ripped, flabby, soft

Fat distribution: chubby, plump, rounded, jiggly, wobbly, flabby, bloated, bloated

Body hair: hairy, smooth, shaven, beard, goatee, mustache, stubble

Weight: light, heavy, average, underweight, overweight, obese, lean, skinny

Body language: confident, nervous, aggressive, submissive, arrogant, timid, confident, relaxed

Body movements: graceful, clunky, fluid, awkward, jerky, smooth, agile, rigid

Build

Muscular: ripped, toned, defined, well-built, buff, brawny, burly, strapping

Athletic: fit, toned, agile, flexible, energetic, muscular, athletic, sporty

Thin: skinny, slender, slim, lanky, bony, gaunt, angular, wiry

Stocky: sturdy, broad-shouldered, compact, muscular, solid, robust, heavy-set

Overweight: plump, chubby, rotund, heavy, portly, corpulent, stout, fleshy

Fat: overweight, overweight, rotund, heavy, bloated, tubby, round, fat

Lean: lanky, slender, skinny, thin, wiry, willowy, spare, underweight

Larger: large, heavy, hefty, substantial, solid, overweight, portly, rotund

Skin

Texture: smooth, soft, silky, rough, bumpy, flaky, scaly, rough

Tone: fair, light, pale, dark, tan, olive, bronze, ruddy, rosy

Complexion: clear, radiant, glowing, dull, blotchy, sallow, ruddy, weathered

Wrinkles: deep, fine, lines, crow's feet, wrinkles, age spots

Marks: freckles, age spots, birthmarks, moles, scars, blemishes, discoloration

Tone: even, uneven, patchy, discolored, mottled, sunburned, windburned

Glow: luminous, radiant, healthy, dull, tired, lifeless

Tautness: taut, firm, loose, saggy, wrinkles, age spots, slack

Condition: healthy, glowing, radiant, dry, oily, acne-prone, sunburned, windburned

Style

Clothing: trendy, stylish, fashionable, outdated, classic, eclectic, casual, formal, conservative, bold, vibrant, plain, ornate

Fabric: silk, cotton, wool, leather, denim, lace, satin, velvet, suede, corduroy

Colors: bright, bold, pastel, neutral, vibrant, muted, monochrome

Accessories: jewelry, hats, glasses, belts, scarves, gloves, watches, necklaces, earrings, bracelets, rings

Shoes: sneakers, boots, sandals, heels, loafers, flats, pumps, oxfords, slippers

Grooming: well-groomed, unkempt, messy, clean-cut, scruffy, neat

Hair: styled, messy, curly, straight, braided, dreadlocks, afro, updo, ponytail

Makeup: natural, bold, minimal, heavy, smokey, colorful, neutral

Personal grooming: clean, fragrant, unkempt, well-groomed, grooming habits

Overall appearance: put-together, disheveled, polished, rough, messy, tidy

If you like what I do and want to support me, please consider buying me a coffee! I also offer editing services and other writing advice on my Ko-fi! Become a member to receive exclusive content, early access, and prioritized writing prompt requests.

#writing prompts#creative writing#writeblr#ask box prompts#how to write#how to describe a character's appearance#how to describe a character#character description#writing help#writing tip#writing tips and tricks#writing advice

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Look in all seriousness you can't redeem a character without showing them being pathetic, deep loser energy. There are no cool redemption arcs. They have to be in the trenches. They have to hate themselves for the mistakes they made. They have to apologize and take whatever is given be it forgiveness or a punch to the jaw. ONLY then will the redemption arc be actually good because it will be cathartic. And then they get to see the good things, they get to be touched gently and held while they sleep.

These things can overlap, even into a circle but without the pathetic loser boy saga your redemption arc will feel hollow.

#redemption arcs#writing#vegas theerapanyakul#kylo ren#anakin skywalker#klaus mikaelson#elijah mikaelson#dameon targeryan#writeblr#am writing#writers on tumblr#writing advice#writing tip#desiblr#writing help#avatar the last airbender#zuko

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

tw: bruises

reference for my fellow whump writers out there

#writing#writer#whump#whumpblr#writing resources#writing research#whump community#angst#writers#writing tips#writing tip#writing prompt#writing challenge#writing inspo#writing inspiration#whump blog#whump prompt#whump prompts#writing prompts#prompt#prompts#writing tropes#writing trope#whump tropes#whump trope#tropes#trope

1K notes

·

View notes