#wittstock family

Text

ROYAL NEWS!!!

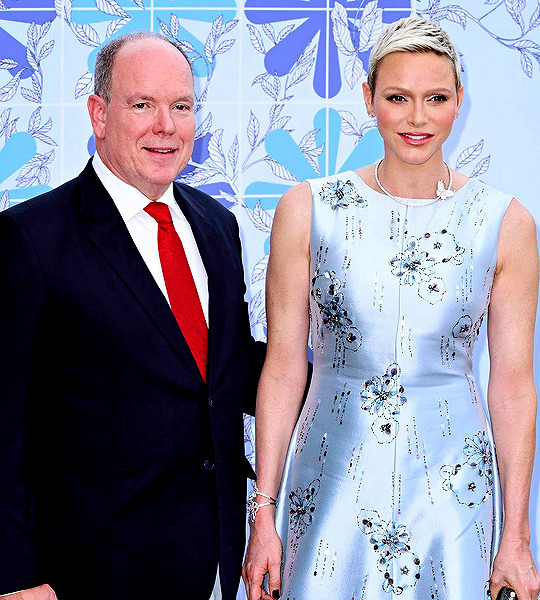

Prince Albert of Monaco officially confirms he and Princess Charlene will attend King Charles' Coronation. He had said months ago, he expected to attend.

#royaltyedit#theroyalsandi#albert ii#prince albert ii#princess charlene#charlene wittstock#monegasque princely family#charles coronation#coronation 2023#my edit#royal news

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summer 2023

#Monaco#prince albert ii#princess charlene#charlene wittstock#prince jacques#princess gabriella#monegasque princely family#house of grimaldi#royals on vacation#candid

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Jacques of Monaco, Princess Gabriella of Monaco and Kaia-Rose Wittstock attend the Monaco's National Day 2023, at The Prince's Palace in Monaco -November 19th 2023.

#prince jacques#princess gabriella#kaia rose wittstock#monegasque princely family#monaco#2023#november 2023#monaco's national day#monaco's national day 2023#royal children#my edit

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would love for you to do an episode on royal adjacent people and them being public personalities. On one hand i get why they would cash in on their association but I also understand why some people might find it tacky. But it is even tackier imo to try to control the lives and earning capabilities of people not even tax payer funded or with titles(tessy, leah behn, amelia windsor). As long as they aren't Martha Louise levels of crazy, I think it's fine.

It's definitely on our list now so we'll get around to it at some point! We talked about similar things in Episode 44 but that was mostly about reality TV, sparked by Mike Tindall, so I think there are other interesting things to explore like Prince Michael's connection to the Russians, the scrutiny of Chris's finances, the families with royal connections like the Midds or the Wittstocks etc. I always enjoy anything about corruption, power, and ethics!

Also I actually had to cut this out because it was a tangent but in the recent episode I talked about ML's beliefs and you know, she's not as kooky as we often think. The example I gave was if you've ever had that experience where you don't really know someone, you've never had a proper conversation with them. But you get a sense from them that they aren't quite right or you don't gel with them. If I had that situation I would say that it's a result of human beings learning to pick up on subconscious cues - body language, tone of voice, the way other people react to someone - after thousands of years of evolution because it benefited our ancestors to be attuned to things without having to consciously recognise them. If ML had that situation she would say that it's a result of someone's aura which comes from another plane of existence. I have a scientific interpretation, she has a spiritual one. I think her views are not things I necessarily agree with but actually lots of royals are into similar stuff to her. She's a bit weird but for a long time she was mostly harmless.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Lesley Chamberlain

The horror of a functioning democracy turning into a brutal dictatorship in a single month is etched into the German psyche. While Nazism claimed millions of victims at home and abroad, it also disfigured the national literary fabric. No biographer, critic or historian of the outstandingly creative 1920s and 1930s can ignore the moment when Hitler’s party, the NSDAP, tore apart the culture of the permissive Weimar Republic by targeting Jews, homosexuals, communists and “degenerate” expressionists. Writers and artists confronted a nightmare, with beatings in the street and storm troops at the door. For the 500 or so who eventually fled, the question was how long to hang on; where to go; how to survive. The panic strained families and ripped lovers apart. Personal loyalties were not always steadfast.

Uwe Wittstock, a prizewinning journalist whose late mother was two years old in 1933, suggests that while we struggle to grasp the catastrophe now, it was all the more unimaginable to its contemporary victims. February 1933: The Winter of Literature revisits moments in those well-documented lives by way of diaries, letters and public events. The personal routines, giddy socializing and creative obsessions belong to some of the best-known names in German culture of the last century, from the monumental novelist Thomas Mann and his brilliant, provocative adult children Erika and Klaus to the communist playwright Bertolt Brecht, the fabulous jazz-age composer Kurt Weill, who was Brecht’s collaborator, and the unforgettable satirical painters Otto Dix and George Grosz.

That transformative February Mann loftily decried his intellectual enemies as “hideous, violent little creatures”. His “Avowal of Socialism” (1922) had made him an enemy of the new regime. Yet he waged a curious battle in his last days in Germany, with his attachment to the high cultural past prompting persistent equivocations. Brecht, meanwhile, had recently written an “instructional play” – one of several such Lehrstücke for revolutionaries – which also made him radically unacceptable. In Erfurt the premiere of Die Maßnahme (The Measures Taken) was prevented by the police. Brecht demanded a bodyguard as he considered ways of escape.

The Nazis targeted not only individuals, but also the democratic institutions they served. Heinrich Mann, Thomas’s brother, fellow novelist and a staunch supporter of the Republic, was eased out of the Prussian Academy of Arts in what struck everyone as a scandal. Fellow academicians, ashamed, found themselves powerless to object. He was a huge name on the literary scene, thanks to Der Untertan and, Professor Unrat, soon to be filmed with Marlene Dietrich as The Blue Angel. Yet so vulnerable was his position that the French ambassador offered him his embassy should he need refuge.

But it is on figures less familiar outside Germany, such as the writer Else Lasker-Schüler, the left-wing editor Carl von Ossietzky and the anarchist poet and playwright Erich Mühsam, that the perverted age extracted particularly brutal revenge. Lasker-Schüler, born in 1869, aged sixty-three in January 1933, was occupying a tiny room in a Berlin hotel when Hitler was elected chancellor. “For a couple of years she [had been] the undisputed queen of Berlin’s bohemian society, boyishly slight, her black hair cut noticeably short, garbed mostly in baggy clothes and velvet jackets with glass-bead necklaces, clattering bangles and rings on every finger.” As Hitler began targeting every aspect of German life, her play Arthur Aronymus was blocked. It had won a coveted award, as the Nazi rag the Völkischer Beobachter fumed: “The daughter of a Bedouin sheikh receives the Kleist Prize!”. As if her clothes were not enough, her latest play featured conflicts between Jews and Christians. The avant-garde director Gustav Hartung was already in trouble with the NSDAP in Darmstadt over plans to produce Brecht’s Saint Joan. To put on the Lasker-Schüler play in Berlin seemed just too provocative. The author, knocked to the ground in her hotel foyer, bit her tongue so hard that she needed stitches.

Ossietzky, meanwhile, as editor of Die Weltbühne (“The World Stage”), the sharpest political and social weekly of the Weimar Republic, had already served two years in prison for decrying German military violations of the Versailles treaty. As the “winter of literature” closed in his friends begged him to flee, but this brave man insisted he would stay “to watch history unfold”.

On February 17 Mühsam rushed to the pub where Ossietzky was speaking that evening and spread the newspaper out on the table. Henceforth Reichsminister Hermann Goering was permitting the police to shoot to kill. “We will probably never see one another again”, Ossietzky responded, but “let us promise … to remain true to ourselves and to stand up with our body and our lives for what we have believed in and fought for”. Meanwhile, on February 18 the disruptive Brownshirts of the SA, Hitler’s Sturmabteilung, broke up the premiere of Kurt Weill’s musical The Silver Lake. Weill, the genius who had set Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera to music, was Jewish. The playwright Georg Kaiser was not – indeed, he was only vaguely leftist – but the Nazis went after him nonetheless. Wittstock doesn’t make the point, but it was a reflection of how politically powerful theatre had been in Germany since the time of the French Revolution that it represented such a threat. Overall, the Nazis feared “Bolshevization” – and their fear of socialist radicalism and artistic modernism stirring up Germany in the Soviet wake was in many ways well founded. The German Communist Party (KPD) would win eighty-one seats in the March 5 election (though its mandates would be annulled three days later). The Nazis especially hated the Jewish Mühsam for his involvement in the briefly established Soviet Bavarian Republic of 1918.

Ossietzky and Mühsam were both arrested in Berlin on February 28, the night after the Reichstag fire, together with the Czechoslovak Communist journalist Egon Erwin Kisch. Kisch, eventually released after ten days because of his foreign passport, witnessed abominable tortures administered to homosexual men at police headquarters. Mühsam held out, but died in a concentration camp in 1934. Ossietzky survived a while longer. The Nobel peace prize for 1935, organized by the future West German president Willy Brandt and awarded to Ossietzky the following year, recognized the courage of his spirit, but his body gave out shortly after the publicity that brought his release.

Throughout that February of 1933, blacklists of every kind grew longer. At her provocative Pfeffermühle (“Pepper Mill”) show in Munich, Erika Mann spotted three sombre figures in the audience taking notes on myriad sexual transgressions and political innuendo. Sex was always an issue for the Nazis (despite the culture minister Joseph Goebbels’s own secret adventures) and cabaret, particularly in Berlin, was an easy target.

Wittstock’s present-tense chronicle is packed with detail, from the crowd that formed a human pyramid so that someone could hand Hitler a rose at his window to the first book-burning in Dresden on March 8. As orgies of destruction spread across the country, university students lined up to pronounce “fire verdicts” on chosen works. “I consign to the flames…”, they chanted, naming Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, essays by the country’s foremost drama critic, Alfred Kerr, and anything by Ossietzky and his outstanding predecessor, the journalist and poet Kurt Tucholsky. Wittstock was mindful of the Capitol riots of January 2021 as he researched his book. He knows that history can repeat itself.

Each of Wittstock’s thirty-five days ends with brief newspaper reports of violent incidents around the country – including news of two brave souls who cut the cable during the broadcast of a Hitler speech – and there is a glossary of what happened to the main characters subsequently. My only criticism is that all this detail doesn’t actually build tension on the page. This reader had to work hard to bring the drama together.

Florian Illies has a more engaging – indeed, at times sensational – style. In Love in a Time of Hate the time span is ten years rather than one month, but many of the characters are the same, shown here in intensely private moments of their suddenly besieged lives. Like Wittstock, Illies immerses us in a stream of gossip (exchanged not least at the Romanisches Café in Berlin), and political rumour, in love affairs past and present, somehow carried on amid great personal achievements and terrible folly. There is a Freudian element and no little writerly brilliance in the way Illies implicitly asks: what did these people mean by love? The question lies at the heart of this racy catalogue raisonée of private passions.

Illies’s entries range beyond Germany to include the outrageous Black dancer Josephine Baker, the cold-hearted young Jean-Paul Sartre and his tortured new partner, Simone de Beauvoir, the Berlin-based fugitives from the Bolshevik Revolution Vladimir Nabokov and his wife, Véra, Picasso and his serial mistresses, and the surrealist painter Salvador Dalí and his devoted Gala (once the wife of the poet Paul Éluard, and still occasionally to be found in his bed). The catalogue of love affairs includes the extravagant bisexual adventures of Marlene Dietrich in America and even the infidelities of Charlie Chaplin, while Christopher Isherwood and Henry Miller look for extreme sex in Berlin and Paris respectively. All these characters and their antics belong to the same era as Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, established in Berlin to clear up, on a wave of post-Freudian enthusiasm, any problems with inhibition and malfunction. This, then, was Europe in love.

Key figures in Illies’s German story are once again Klaus and Erika Mann, their choices homosexual and occasionally incestuous. The serial heterosexual loves of their uncle Heinrich also feature, though it’s his poor taste in women that upsets the family when they reunite in exile. (The erratic behaviour of his alcoholic wife, Nelly Kröger, he tries to blame on a fall.) Well known but worth repeating is the record-breaking callousness of Brecht as anti-lover of the decade. Unlike the novelist Hermann Hesse, who only left his bride to honeymoon alone, Brecht left his actual wedding to the actress Helene Weigel to spend the evening with his mistress. “Here you have someone on whom you can’t rely”, he told each new conquest, perhaps believing that exculpated him. Illies has some astonishing vignettes, all related, like Wittstock, in the present tense. One was the moment when Baker was bowled over by the modernist architect Le Corbusier. Soon they were dressing up as each other, an erotic encounter culminating in the shower, with Josephine washing the black make-up off Corb’s white skin. Another was the plight of Thea Sternheim, whose ex-husband, the playwright Carl, was raving with tertiary syphilis while Klaus Mann introduced their untameable daughter Mopsa to cocaine. Thea rented adjacent flats to house her loved ones. But then Pamela Wedekind, daughter of the playwright Frank, former lover of Erika Mann and now fiancée of the dying Carl, moved in too. Thea, distraught, begged for opiate injections from her ex’s carer.

If this was the age of “the New Objectivity” in Germany, it was also, in Erich Kästner’s variation on the theme, the age of Reasonable Romance. It seems to have been a value-free erotic zone stretching from Munich to Berlin, Vienna to Paris. Its actors had little concern for politics, except when it spoilt the fun. Nightclubs and foreign travel, great villas built on some of Europe’s most beautiful coasts: such were the backdrops to their realized dreams. When numerous leading intellectuals were forced to bed down for a short idyllic summer beside the Mediterranean, it didn’t seem like the Hitler emergency at all. When the Mann family held court at Sanary-sur-Mer from June to September 1933, Aldous Huxley and Sybille Bedford, as well as the German writer Lion Feuchtwanger in his mansion on the cliffs, were their near neighbours.

Only the expressionist poet Gottfried Benn complained, in a letter to Klaus Mann: “Do you think history is particularly active in French seaside resorts?”. This is an odd question, because it sounds as if Benn had really had too much of Marxist-inclined German writers occupying the moral high ground. But it does have some critical force, helping to pinpoint two European ways of being culturally modern – a New Man, a New Woman – in the early twentieth century. You could be a ruthless communist theoretician. Or you could be a sun-worshipping, god-building, car-driving, sex-crazed, drug-addled individualist.

Or, indeed, you could be Benn, a practising doctor and brilliant poet who, back in a Berlin he would never leave, was setting a new standard for the merciless “objective” coldness of the age. “Life is the building of bridges over rivers that seep away” seems like decent enough German pessimism; “Love is a crisis of the organs of touch” is simply cruel. Benn still attracted a steady stream of women, one of whom, invited for a drink to his flat for the first time, felt that, dressed in his medical white coat, he was going to dissect her with surgical instruments. Was it Benn’s coldness that led him to invest emotionally in the Nazi vision of a new civilization? His fellow writers tried to dissuade him from advancing his uncongenial views, as if they didn’t really take him seriously. The Nazis left him alone because they didn’t want the support of an expressionist degenerate. When his muse returned he wrote some of the greatest poems of the century.

In his novel Mephisto Klaus Mann had based the main character on Gustaf Gründgens, the former husband of his lesbian sister. The three made a foursome, on occasion, with Pamela Wedekind. Illies’s book is full of such permutations, as if all the sexual taboos dictated by culture had vanished in a new age. Many of the heterosexual Weimar-era men believed that their creativity depended on pain, violence and new conquest, at whatever cost to their discarded partners. Neither of these books analyses the extremes it chronicles, but one remembers the strange and ambivalent role played by sexuality in Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (originally drafted in 1944), where the culture of Reason, now apparently reaching its apotheosis in Hitler, was somehow the product of rechannelled sexual aggression. A kind of sexuality hitherto underground had become a new extreme cultural and political force.

So what of love, in the end? Some of the most moving stories here concern children and pets. When sex was out of the way everyone behaved better. Ex-spouses helped each other in extremis. Wittstock has the marvellous story of how Brecht and Helene Weigel had their daughter, Barbara, smuggled out of Augsburg with the help of a German nanny and an Englishwoman living in Vienna. Irene Grant, with her four-year-old son on her passport, crossed the border and brought Barbara, two and a half, dressed as a boy, to her parents. (My own husband had a similar escape six years later.) The singer Lotte Lenya had divorced Kurt Weill, but then he helped her to escape Germany and eventually they got back together. Other friends made sure that Weill was reunited in exile with his dog. Back in Berlin, much worry went into not abandoning Gründgens’s sheepdog, Haari.

They were all enemies of Nazism, certainly. But what kind of politics, what kind of society, would have best suited this licentious, aesthetic-minded generation, with its gigantic artistic talents and potential for deep moral waywardness? Presumably, our ultra-liberal own. Perhaps that’s why Illies remains so reserved in his moral judgements, finding the antisemitic vamp Alma Mahler pretty nasty, but only the Hitler-loving film-maker Leni Riefenstahl (“there was a strong streak of elitism to her nymphomania”) “diabolical”. He’s rather lenient, to this reviewer’s mind, and rather hard on Thomas Mann’s “noun-heavy moralizing”. I would have liked to hear him call Brecht not only a great artist, but also a pernicious moral fraud. Illies engages with some relish in his tale, where Wittstock, two generations older, is outraged and sad. In m

aking these observations, though, I may be the product of a staider generation. So let me conclude by saying that, for all the compelling studies on the Weimar Republic, no one will want to miss either of these well-translated books on Weimar writers and Weimar in love.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh, GCVO, GCStJ, CD (born Sophie Helen Rhys-Jones, 20 January 1965)

20 January 2024

Today is a special day in the calendar of the British royal family as Sophie, Duchess of Edinburgh, celebrates her 59th birthday.

The Duchess of Edinburgh has earned herself many loyal watchers over the years as she has attended charity events, made visits to organisations that matter to her, and been spotted at historic royal events.

Prince Edward's wife has worn some supremely elegant looks over the years.

We are sure that as she enters her 59th year and her first full years as the Duchess of Edinburgh, she will continue to pull out the stops in all the public outings to come.

A Regal Vision

The state visit of the president of the Republic Of Korea in 2023 was a momentous occasion.

The Duchess did not disappoint, in fact, she stunned in a glorious white Suzannah London dress.

The elegant gown featured a sheer embroidered panel on the shoulders and up the neck for an ethereal touch.

It also had long sleeves that were cuffed at the wrist. The royal styled the piece with the breathtaking aquamarine tiara and a modest silver clutch.

A Barbie Moment

In June 2022, the then-Countess of Wessex stunned in a block colour moment next to her sister-in-law, the then-Duchess of Cambridge.

The royal ladies attended the Order of The Garter service at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, where Sophie stunned in a bubblegum pink A-line dress with long fluted sleeves and a rounded neck.

She paired the knee-length piece with a pair of nude heels, a beige floral and feathered fascinator, and a beige croc-print clutch.

Festive Blues

The Duchess attended the Christmas Day church service at Church of St Mary Magdalene on the Sandringham estate in 2018.

She pulled out one of her numerous fabulous dress coats. Sophie rocked the cornflower blue belted piece with a pair of navy tights, black platform heels, and a pair of chic black leather gloves.

Peeking out from the top of the coat was a blue and black ditsy floral printed dress with a ruffled neckline. Her black netted fascinator completed the look.

A Bronzey Moment

In 2021, Sophie once again embraced blue but in a totally different way.

The royal was seen arriving at the biennial Rifles Awards Dinner at the City of London Guildhall wearing a stunning aquamarine floor-length evening dress with a square neckline and cinched waistline.

The bronzed Duchess teamed the dress with a glitzy clutch in blue and black sequins and flesh-coloured shiny pointed-toe heels.

The perfect finishing touches were added in the form of a diamond-encrusted brooch and coordinating drop earrings that were shown off by her hair being styled in an elegant updo.

The Picture-Perfect Wedding Guest

In 2021, Sophie was photographed alongside her husband, the then-Earl of Wessex, at the wedding of Flora Ogilvy, granddaughter of Princess Alexandra, to Timothy Vesterberg, at St James's Church in Piccadilly, London.

The Duchess looked stunning in a rosy pink shin-length A-line dress, which featured cinching around the neck and on the cut-off sleeves.

She coordinated the pink dress with a cream clutch adorned with pink raffia flowers, a pair of cream patent heels with a buckle around the ankle, and the pièce de résistance was a cream lace fascinator with a corsage detail.

Trendy Taupe

The Duchess is known for getting out her best looks when she attends a special wedding.

In 2011, she was seen with her husband Prince Edward leaving the Hotel de Paris to attend the religious ceremony of the royal wedding of Prince Albert II of Monaco to Charlene Wittstock in Monaco.

The royal opted for a taupe aesthetic that with the 90s fashion revival we have seen over the last year and the wearing of trendy browns is a look that would go down well today.

The then-46-year-old Sophie paired the taupe piece with a cowl neckline with a coordinating feathered fascinator, ruched clutch, and peep-toe heels.

A Classic LBD

In 2014, Sophie switched it up entirely and opted for a classic little black dress that exuded glamour.

The royal was pictured alongside Strictly host Tess Daly at the star-studded St John Ambulance Everyday Heroes celebration of the nation's life savers at the Royal Lancaster Hotel in 2014.

The Duchess's floor-length gown had a diamanté-encrusted halterneck and she swept her hair over to one side for an effortless look.

#Duchess of Edinburgh#Sophie Duchess of Edinburgh#Sophie Helen Rhys-Jones#British Royal Family#Countess of Wessex#fashion#style

1 note

·

View note

Text

By Lesley Chamberlain

The horror of a functioning democracy turning into a brutal dictatorship in a single month is etched into the German psyche. While Nazism claimed millions of victims at home and abroad, it also disfigured the national literary fabric. No biographer, critic or historian of the outstandingly creative 1920s and 1930s can ignore the moment when Hitler’s party, the NSDAP, tore apart the culture of the permissive Weimar Republic by targeting Jews, homosexuals, communists and “degenerate” expressionists. Writers and artists confronted a nightmare, with beatings in the street and storm troops at the door. For the 500 or so who eventually fled, the question was how long to hang on; where to go; how to survive. The panic strained families and ripped lovers apart. Personal loyalties were not always steadfast.

Uwe Wittstock, a prizewinning journalist whose late mother was two years old in 1933, suggests that while we struggle to grasp the catastrophe now, it was all the more unimaginable to its contemporary victims. February 1933: The Winter of Literature revisits moments in those well-documented lives by way of diaries, letters and public events. The personal routines, giddy socializing and creative obsessions belong to some of the best-known names in German culture of the last century, from the monumental novelist Thomas Mann and his brilliant, provocative adult children Erika and Klaus to the communist playwright Bertolt Brecht, the fabulous jazz-age composer Kurt Weill, who was Brecht’s collaborator, and the unforgettable satirical painters Otto Dix and George Grosz.

That transformative February Mann loftily decried his intellectual enemies as “hideous, violent little creatures”. His “Avowal of Socialism” (1922) had made him an enemy of the new regime. Yet he waged a curious battle in his last days in Germany, with his attachment to the high cultural past prompting persistent equivocations. Brecht, meanwhile, had recently written an “instructional play” – one of several such Lehrstücke for revolutionaries – which also made him radically unacceptable. In Erfurt the premiere of Die Maßnahme (The Measures Taken) was prevented by the police. Brecht demanded a bodyguard as he considered ways of escape.

The Nazis targeted not only individuals, but also the democratic institutions they served. Heinrich Mann, Thomas’s brother, fellow novelist and a staunch supporter of the Republic, was eased out of the Prussian Academy of Arts in what struck everyone as a scandal. Fellow academicians, ashamed, found themselves powerless to object. He was a huge name on the literary scene, thanks to Der Untertan and, Professor Unrat, soon to be filmed with Marlene Dietrich as The Blue Angel. Yet so vulnerable was his position that the French ambassador offered him his embassy should he need refuge.

But it is on figures less familiar outside Germany, such as the writer Else Lasker-Schüler, the left-wing editor Carl von Ossietzky and the anarchist poet and playwright Erich Mühsam, that the perverted age extracted particularly brutal revenge. Lasker-Schüler, born in 1869, aged sixty-three in January 1933, was occupying a tiny room in a Berlin hotel when Hitler was elected chancellor. “For a couple of years she [had been] the undisputed queen of Berlin’s bohemian society, boyishly slight, her black hair cut noticeably short, garbed mostly in baggy clothes and velvet jackets with glass-bead necklaces, clattering bangles and rings on every finger.” As Hitler began targeting every aspect of German life, her play Arthur Aronymus was blocked. It had won a coveted award, as the Nazi rag the Völkischer Beobachter fumed: “The daughter of a Bedouin sheikh receives the Kleist Prize!”. As if her clothes were not enough, her latest play featured conflicts between Jews and Christians. The avant-garde director Gustav Hartung was already in trouble with the NSDAP in Darmstadt over plans to produce Brecht’s Saint Joan. To put on the Lasker-Schüler play in Berlin seemed just too provocative. The author, knocked to the ground in her hotel foyer, bit her tongue so hard that she needed stitches.

Ossietzky, meanwhile, as editor of Die Weltbühne (“The World Stage”), the sharpest political and social weekly of the Weimar Republic, had already served two years in prison for decrying German military violations of the Versailles treaty. As the “winter of literature” closed in his friends begged him to flee, but this brave man insisted he would stay “to watch history unfold”.

On February 17 Mühsam rushed to the pub where Ossietzky was speaking that evening and spread the newspaper out on the table. Henceforth Reichsminister Hermann Goering was permitting the police to shoot to kill. “We will probably never see one another again”, Ossietzky responded, but “let us promise … to remain true to ourselves and to stand up with our body and our lives for what we have believed in and fought for”. Meanwhile, on February 18 the disruptive Brownshirts of the SA, Hitler’s Sturmabteilung, broke up the premiere of Kurt Weill’s musical The Silver Lake. Weill, the genius who had set Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera to music, was Jewish. The playwright Georg Kaiser was not – indeed, he was only vaguely leftist – but the Nazis went after him nonetheless. Wittstock doesn’t make the point, but it was a reflection of how politically powerful theatre had been in Germany since the time of the French Revolution that it represented such a threat. Overall, the Nazis feared “Bolshevization” – and their fear of socialist radicalism and artistic modernism stirring up Germany in the Soviet wake was in many ways well founded. The German Communist Party (KPD) would win eighty-one seats in the March 5 election (though its mandates would be annulled three days later). The Nazis especially hated the Jewish Mühsam for his involvement in the briefly established Soviet Bavarian Republic of 1918.

Ossietzky and Mühsam were both arrested in Berlin on February 28, the night after the Reichstag fire, together with the Czechoslovak Communist journalist Egon Erwin Kisch. Kisch, eventually released after ten days because of his foreign passport, witnessed abominable tortures administered to homosexual men at police headquarters. Mühsam held out, but died in a concentration camp in 1934. Ossietzky survived a while longer. The Nobel peace prize for 1935, organized by the future West German president Willy Brandt and awarded to Ossietzky the following year, recognized the courage of his spirit, but his body gave out shortly after the publicity that brought his release.

Throughout that February of 1933, blacklists of every kind grew longer. At her provocative Pfeffermühle (“Pepper Mill”) show in Munich, Erika Mann spotted three sombre figures in the audience taking notes on myriad sexual transgressions and political innuendo. Sex was always an issue for the Nazis (despite the culture minister Joseph Goebbels’s own secret adventures) and cabaret, particularly in Berlin, was an easy target.

Wittstock’s present-tense chronicle is packed with detail, from the crowd that formed a human pyramid so that someone could hand Hitler a rose at his window to the first book-burning in Dresden on March 8. As orgies of destruction spread across the country, university students lined up to pronounce “fire verdicts” on chosen works. “I consign to the flames…”, they chanted, naming Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, essays by the country’s foremost drama critic, Alfred Kerr, and anything by Ossietzky and his outstanding predecessor, the journalist and poet Kurt Tucholsky. Wittstock was mindful of the Capitol riots of January 2021 as he researched his book. He knows that history can repeat itself.

Each of Wittstock’s thirty-five days ends with brief newspaper reports of violent incidents around the country – including news of two brave souls who cut the cable during the broadcast of a Hitler speech – and there is a glossary of what happened to the main characters subsequently. My only criticism is that all this detail doesn’t actually build tension on the page. This reader had to work hard to bring the drama together.

Florian Illies has a more engaging – indeed, at times sensational – style. In Love in a Time of Hate the time span is ten years rather than one month, but many of the characters are the same, shown here in intensely private moments of their suddenly besieged lives. Like Wittstock, Illies immerses us in a stream of gossip (exchanged not least at the Romanisches Café in Berlin), and political rumour, in love affairs past and present, somehow carried on amid great personal achievements and terrible folly. There is a Freudian element and no little writerly brilliance in the way Illies implicitly asks: what did these people mean by love? The question lies at the heart of this racy catalogue raisonée of private passions.

Illies’s entries range beyond Germany to include the outrageous Black dancer Josephine Baker, the cold-hearted young Jean-Paul Sartre and his tortured new partner, Simone de Beauvoir, the Berlin-based fugitives from the Bolshevik Revolution Vladimir Nabokov and his wife, Véra, Picasso and his serial mistresses, and the surrealist painter Salvador Dalí and his devoted Gala (once the wife of the poet Paul Éluard, and still occasionally to be found in his bed). The catalogue of love affairs includes the extravagant bisexual adventures of Marlene Dietrich in America and even the infidelities of Charlie Chaplin, while Christopher Isherwood and Henry Miller look for extreme sex in Berlin and Paris respectively. All these characters and their antics belong to the same era as Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, established in Berlin to clear up, on a wave of post-Freudian enthusiasm, any problems with inhibition and malfunction. This, then, was Europe in love.

Key figures in Illies’s German story are once again Klaus and Erika Mann, their choices homosexual and occasionally incestuous. The serial heterosexual loves of their uncle Heinrich also feature, though it’s his poor taste in women that upsets the family when they reunite in exile. (The erratic behaviour of his alcoholic wife, Nelly Kröger, he tries to blame on a fall.) Well known but worth repeating is the record-breaking callousness of Brecht as anti-lover of the decade. Unlike the novelist Hermann Hesse, who only left his bride to honeymoon alone, Brecht left his actual wedding to the actress Helene Weigel to spend the evening with his mistress. “Here you have someone on whom you can’t rely”, he told each new conquest, perhaps believing that exculpated him. Illies has some astonishing vignettes, all related, like Wittstock, in the present tense. One was the moment when Baker was bowled over by the modernist architect Le Corbusier. Soon they were dressing up as each other, an erotic encounter culminating in the shower, with Josephine washing the black make-up off Corb’s white skin. Another was the plight of Thea Sternheim, whose ex-husband, the playwright Carl, was raving with tertiary syphilis while Klaus Mann introduced their untameable daughter Mopsa to cocaine. Thea rented adjacent flats to house her loved ones. But then Pamela Wedekind, daughter of the playwright Frank, former lover of Erika Mann and now fiancée of the dying Carl, moved in too. Thea, distraught, begged for opiate injections from her ex’s carer.

If this was the age of “the New Objectivity” in Germany, it was also, in Erich Kästner’s variation on the theme, the age of Reasonable Romance. It seems to have been a value-free erotic zone stretching from Munich to Berlin, Vienna to Paris. Its actors had little concern for politics, except when it spoilt the fun. Nightclubs and foreign travel, great villas built on some of Europe’s most beautiful coasts: such were the backdrops to their realized dreams. When numerous leading intellectuals were forced to bed down for a short idyllic summer beside the Mediterranean, it didn’t seem like the Hitler emergency at all. When the Mann family held court at Sanary-sur-Mer from June to September 1933, Aldous Huxley and Sybille Bedford, as well as the German writer Lion Feuchtwanger in his mansion on the cliffs, were their near neighbours.

Only the expressionist poet Gottfried Benn complained, in a letter to Klaus Mann: “Do you think history is particularly active in French seaside resorts?”. This is an odd question, because it sounds as if Benn had really had too much of Marxist-inclined German writers occupying the moral high ground. But it does have some critical force, helping to pinpoint two European ways of being culturally modern – a New Man, a New Woman – in the early twentieth century. You could be a ruthless communist theoretician. Or you could be a sun-worshipping, god-building, car-driving, sex-crazed, drug-addled individualist.

Or, indeed, you could be Benn, a practising doctor and brilliant poet who, back in a Berlin he would never leave, was setting a new standard for the merciless “objective” coldness of the age. “Life is the building of bridges over rivers that seep away” seems like decent enough German pessimism; “Love is a crisis of the organs of touch” is simply cruel. Benn still attracted a steady stream of women, one of whom, invited for a drink to his flat for the first time, felt that, dressed in his medical white coat, he was going to dissect her with surgical instruments. Was it Benn’s coldness that led him to invest emotionally in the Nazi vision of a new civilization? His fellow writers tried to dissuade him from advancing his uncongenial views, as if they didn’t really take him seriously. The Nazis left him alone because they didn’t want the support of an expressionist degenerate. When his muse returned he wrote some of the greatest poems of the century.

In his novel Mephisto Klaus Mann had based the main character on Gustaf Gründgens, the former husband of his lesbian sister. The three made a foursome, on occasion, with Pamela Wedekind. Illies’s book is full of such permutations, as if all the sexual taboos dictated by culture had vanished in a new age. Many of the heterosexual Weimar-era men believed that their creativity depended on pain, violence and new conquest, at whatever cost to their discarded partners. Neither of these books analyses the extremes it chronicles, but one remembers the strange and ambivalent role played by sexuality in Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (originally drafted in 1944), where the culture of Reason, now apparently reaching its apotheosis in Hitler, was somehow the product of rechannelled sexual aggression. A kind of sexuality hitherto underground had become a new extreme cultural and political force.

So what of love, in the end? Some of the most moving stories here concern children and pets. When sex was out of the way everyone behaved better. Ex-spouses helped each other in extremis. Wittstock has the marvellous story of how Brecht and Helene Weigel had their daughter, Barbara, smuggled out of Augsburg with the help of a German nanny and an Englishwoman living in Vienna. Irene Grant, with her four-year-old son on her passport, crossed the border and brought Barbara, two and a half, dressed as a boy, to her parents. (My own husband had a similar escape six years later.) The singer Lotte Lenya had divorced Kurt Weill, but then he helped her to escape Germany and eventually they got back together. Other friends made sure that Weill was reunited in exile with his dog. Back in Berlin, much worry went into not abandoning Gründgens’s sheepdog, Haari.

They were all enemies of Nazism, certainly. But what kind of politics, what kind of society, would have best suited this licentious, aesthetic-minded generation, with its gigantic artistic talents and potential for deep moral waywardness? Presumably, our ultra-liberal own. Perhaps that’s why Illies remains so reserved in his moral judgements, finding the antisemitic vamp Alma Mahler pretty nasty, but only the Hitler-loving film-maker Leni Riefenstahl (“there was a strong streak of elitism to her nymphomania”) “diabolical”. He’s rather lenient, to this reviewer’s mind, and rather hard on Thomas Mann’s “noun-heavy moralizing”. I would have liked to hear him call Brecht not only a great artist, but also a pernicious moral fraud. Illies engages with some relish in his tale, where Wittstock, two generations older, is outraged and sad. In m

aking these observations, though, I may be the product of a staider generation. So let me conclude by saying that, for all the compelling studies on the Weimar Republic, no one will want to miss either of these well-translated books on Weimar writers and Weimar in love.

0 notes

Text

Erstmals seit Genesung Charlène zeigt sich wieder in Öffentlichkeit

30.04.2022, 21:16 Uhr

Monatelang muss Charlène von Monaco in einer Klinik behandelt werden. Mitte April kehrt die Fürstin schließlich zu ihrer Familie in den Palast zurück. Am Wochenende tritt sie erstmals wieder öffentlich auf.

Zum ersten Mal seit ihrer Rückkehr nach Monaco zeigte sich Fürstin Charlène in der Öffentlichkeit. Bei der FIA-Formel-E-Weltmeisterschaft, einem Rennen für elektrobetriebene Formelwagen, zeigte sie sich am Wochenende in Monaco mit Ehemann Fürst sowie ihren Zwillingen Jacques und Gabriella. Fotos zeigten sie mit kurzen hellblonden Haaren und dunkelgrauem Anzug. Erst Mitte März war Charlène nach einem Klinikaufenthalt wieder nach Monaco zurückgekehrt. Zu Beginn des vergangenen Jahres reiste sie in ihre Heimat Südafrika, um den Kampf gegen die Nashorn-Wilderei zu unterstützen. Schon bald saß sie dann aber mit Gesundheitsproblemen am Kap fest. Wegen einer Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Entzündung durfte sie nicht reisen. Mehrfach musste Charlène dann am Südzipfel Afrikas stundenlang unter Vollnarkose operiert werden, hielt sich wegen des schleppenden Heilungsprozesses zeitweilig auch in einer Klinik auf. Mitte November kehrte due Fürstin endlich nach Monaco zurück - nur um kurz darauf zur medizinischen Behandlung in eine Klinik außerhalb des Fürstentums zu reisen. Zuhause soll sie sich noch immer erholen. Charlènes Trennung von der Familie war ungewöhnlich lang und hatte zunächst für viele Spekulationen gesorgt. Der Palast schrieb damals von einem Zustand allgemeiner Erschöpfung, später nannte das Haus auch Zahnprobleme als Grund für den rund vier Monate langen Klinikaufenthalt. Fürst Albert II. sagte in einem Interview, seine Frau leide unter körperlicher und emotionaler Erschöpfung.

Die frühere Karriereschwimmerin Charlène Wittstock wurde 1978 im heutigen Simbabwe geboren, mit zwölf Jahren zog sie mit ihrer Familie nach Südafrika. Ihren späteren Mann lernte sie im Jahr 2000 bei einem Schwimmwettkampf in Monaco kennen. 2007 siedelte sie dann in den Stadtstaat am Mittelmeer über. Seit 2011 ist sie Fürstin.

0 notes

Text

Prince Albert of Monaco thoughts on the Oprah interview.

“This kind of display of public dissatisfaction, to say the least, these type of conversations should be held within the intimate quarters of the family. It doesn't really have to be laid out in the public sphere like that,' he says. 'So it did bother me a little bit. I can understand where they are coming from in a certain way but I think it wasn't the appropriate forum to be able to have these kinds of discussions.'

#prince harry#prince albert#uk#monaco#charlene wittstock#royals#duchess of sussex#duke of sussex#harry and meghan#meghan and harry x oprah#oprah#oprah interview#opinion#thoughts#royal family#the royal family#fridaymood#usa#news#breaking news

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

✵ July 2, 2011 ✵

Charlene Wittstock & Prince Albert II of Monaco, Sovereign Prince of Monaco

#charlene wittstock#princess charlene#Prince Albert II#Albert#Prince Albert#Albert II#armani#armani wedding dress#royal wedding dress#beaded wedding dress#embroidered wedding dress#royal wedding veil#military uniform#Monegasque Princely Family#Monegasque Royal Family#monegasque princely wedding#monegasque royal wedding#Monaco#Monaco Royal Family#princes palace of monaco#monaco princely family#monaco royal wedding#monaco princely wedding#House of Grimaldi#Royal Wedding

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Princess Charlene visited the Residence a Qietüdine retirement home in Monaco. | July 26, 2022

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

#denmark#crown princess mary#mary donaldson#danish royal family#house of glucksburg#monaco#princess charlene#charlene wittstock#monagasque princely family#house of grimaldi#who wore it best

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Albert II of Monaco, Princess Charlène of Monaco, Prince Jacques of Monaco, Princess Gabriella of Monaco, Raigen Wittstock and Aiva-Grace Wittstock participate in the late Prince Rainier III's 100th birth anniversary celebrations in Monaco -May 31st 2023.

#prince albert#prince albert ii#princess charlene#prince jacques#princess gabriella#raigen wittstock#aiva grace wittstock#monegasque royal family#monaco#2023#may 2023#prince rainier#prince rainier iii's 100th birth anniversary#royal children#my edit

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

8th May 2021 // Prince Jacques and Princess Gabriella having the time of their life at the Monaco E-Prix with their cousin Kaia-Rose Wittstock

90 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ocean Tiara ♕ Princess Charlene

#charlene wittstock#princess charlene#Charlene of Monaco#ocean tiara#sapphire tiara#Diamond Tiara#Diamond Jewelry#diamond jewels#sapphire jewelry#personal property#personal jewelry#royal wedding gift#royal gift#necklace tiara#Monaco#Monaco Royal Family#monaco princely family#monaco princely jewels#monaco royal jewels#Monegasque Royal Family#Monegasque Princely Family#monegasque royal jewels#monegasque princely jewels#House of Grimaldi#crown jewels

55 notes

·

View notes

Photo

❃ ✯ ❃ Ten Favorites ❃ ✯ ❃

Royal Wedding Dress Trains

Charlene Wittstock wearing Armani Prive

#ten favorites#charlene wittstock#princess charlene#armani#royal wedding dress#Royal Wedding Dress Train#Wedding Dress Train#Monegasque Royal Family#Monaco Royal Family#Royal Fashion#royal weddings

13 notes

·

View notes