#vocabulary

Note

whats up?? would you mind giving prompts for “movement”? take for example: “She walks over to the boy”. Instead of saying “She walks”, i would like something more creative?

Synonyms for "Walk"

stroll

saunter

amble

trudge

plod

march

stride

wander

ramble

advance

make one's way

traipse

prowl

skip

Synonyms for "run"

dart

sprint

rush

dash

hurry

scurry

scuttle

charge

gallop

bound

fly

scamper

sprint

race

jog

trot

I hope this helps! Let me know if I got what you wanted :)

#writers and poets#writing#creative writing#creative writers#helping writers#writers on tumblr#writeblr#let's write#poets and writers#resources for writers#writer on tumblr#writer stuff#writer problems#writer community#writer things#writerscommunity#writblr#writers of tumblr#writers life#writers block#writers community#vocabulary#writing practice#writing prompt#writing inspiration#writing advice#on writing#writing community#writing tips#writer

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

How do you know when a story is worth telling?

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare English Words

Epoch -- a particular period of time in history or a person’s life

Intransigent -- refusing to agree or compromise

Beamish -- bright, cheerful, optimistic

Insouciant -- free from worry, concern, or anxiety

Veridical -- truthful

Effulgent -- shining forth brilliantly; radiant

Venetus -- having the color of the deep blue sea

Orphic -- mysterious and entrancing; beyond ordinary understanding

Eldritch -- eerie; weird; spooky

Esoteric -- intended for or likely to be understood by only a select few; private; secret

Rout -- to howl as the wind; make a roaring noise

Aeonian -- eternal; everlasting

Verendus -- to be feared; worthy of reverence; giving an appearance of aged goodness

#langblr#language#writing#writeblr#writers#resource#resources#writing resources#vocabulary#vocab#english vocab#english vocabulary#rare english words#rare words

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

We ask your questions so you don’t have to! Submit your questions to have them posted anonymously as polls.

#polls#incognito polls#anonymous#tumblr polls#tumblr users#questions#polls about language#submitted nov 20#language#definitions#vocabulary

827 notes

·

View notes

Photo

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Colon didn't reply. I wish Captain Vimes were here, he thought. He wouldn't have known what to do either, but he's got a much better vocabulary to be baffled in.

Terry Pratchett, Guards! Guards!

#fred colon#sam vimes#samuel vimes#guards! guards!#discworld#terry pratchett#character description#chain of command#authority#faking it#vocabulary#wishful thinking#baffled#what do i do

535 notes

·

View notes

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

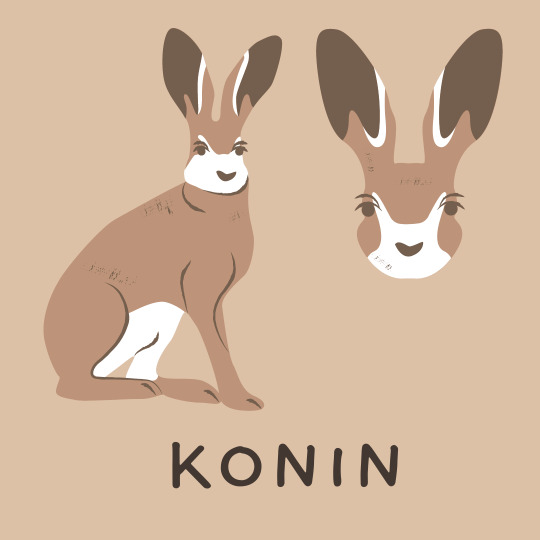

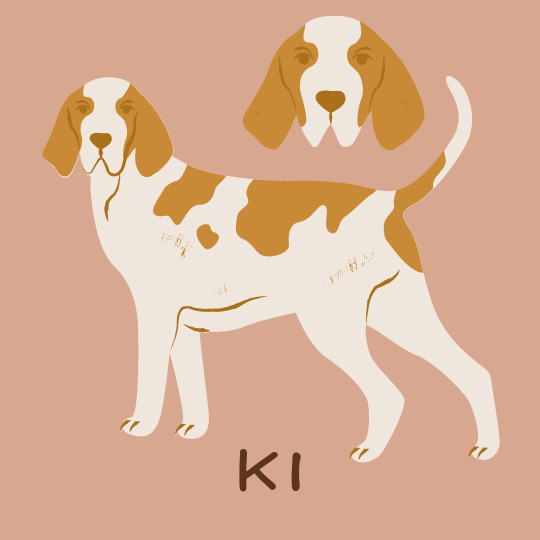

Photo

Bestys yn Kernewek “Beasties in Cornish”

#cornish#kernewek#kernowek#teangacha ceilteacha#mo fhoilseachán#languages#langblr#vocabulary#language tumblr#celtic languages

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

ancient greek words for colors:

On the whole, the Greeks were not really concerned with giving names to specific colors. Their color terms were vague, often had more to do with shade than color difference, and drew in a sort of dynamic physicality that is honestly incredibly interesting.

μέλας and λευκός, which were commonly used to refer to black and white respectively, were still more involved with shade than the particular colors that we perceive as black and white. μέλας also meant dark, murky, and swarthy. λευκός was light, bright and clear, referred to any white color from a pure white to a light grey, and could also refer to someone with lighter skin.

χλωρός meant pale green or greenish yellow, but also commonly meant pale or pallid when referring to people and fresh or blooming when referring to plants and liquids (including blood and tears).

πορφύρεος is where we get the color term purple. And when it was referring to clothes or things, it did mean purple. But when it was describing people, especially their complexions, it meant bright red or flushed. This definition originates from the basic meaning of the word: heaving, surging, gushing, coming from the verb πορφύρω.

ξανθός and ἐρυθρός are perhaps the only straightforward terms, meaning yellow or golden and red respectively. ξανθός was typically used to describe blonde (ish) people; Achilles is described as having ξανθή κόμη (golden hair).

γλαυκός was commonly used to refer to the color grey, or simply to describe something as gleaming. When it refers to eyes, it usually describes the color; the most famous example being Athena and her epithet of γλαυκῶπις or grey-eyed (or gleaming eyed).

And now let's talk about κυάνεος. We get the color term cyan from it, and the word is popularly considered to refer to a dark blue. But that isn't exactly accurate. If we look at what this word typically described: hair, people, etc., it is clear that the concept of blue that we have nowadays wasn’t really coming into play. In fact, the more general translation is dark or black, conveying a shade rather than a color, like μέλας. If I were to attribute a color term to this word at all, I would probably say blue-black, or a cool black, to convey the depth of that shade, which is probably what the Greeks were describing.

#ancient greek#vocab#vocabulary#language learning#greek language#greek vocab#classical literature#classics#colors#words for colors#how to describe colors#dys blurbs#i had to make my own list because every other one i've seen has colors that aren't referred to by texts with as much frequency#achilles#athena#the iliad#the odyssey

519 notes

·

View notes

Text

Basic quantifiers in Japanese

台 (だい) - used for cars, bicycles, machines, mechanical devices, household appliances

杯 (はい) - used for cups and glasses

匹 (ひき) - used for small animals

本 (ほん) - used for long and thin objects

階 (かい) - used for floors

回 (かい) - used for occurrences, numer of times

個 (こ) - used for things that are small and round

枚 (まい) - used for thin and flat objects

人 (にん) - used for people (but we say 一人 (ひとり) for one person and 二人(ふたり)for two

冊 (さつ) - used for books

歳 (さい) - used for age

Plus general quantifiers:

一つ (ひとつ)

二つ (ふたつ)

三つ (みっつ)

四つ (よっつ)

五つ (いつつ)

六つ (むっつ)

七つ (ななつ)

八つ (やっつ)

九つ (ここのつ)

十 (とお)

#japanese#langblr#japanese langblr#vocabulary#japanese language#studyblr#japanese vocabulary#food vocabulary#vocabulary list#learning japanese#mine

760 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vocabulary

Words to Describe Sound

✷

↠ bang

↠ bark

↠ beep

↠ bellow

↠ blare

↠ blast

↠ bong

↠ boom

↠ buzz

↠ cackle

↠ cheep

↠ chime

↠ chirp

↠ clack

↠ clang

↠ clank

↠ clap

↠ clatter

↠ click

↠ clink

↠ cluck

↠ clunk

↠ crack

↠ crackle

↠ crash

↠ creak

↠ crinkle

↠ drip

↠ drum

↠ fizz

↠ gnash

↠ gobble

↠ grate

↠ grind

↠ groan

↠ growl

↠ grumble

↠ grunt

↠ gurgle

↠ hiss

↠ hoot

↠ howl

↠ hum

↠ jangle

↠ jingle

↠ knock

↠ moan

↠ neigh

↠ patter

↠ peep

↠ ping

↠ pop

↠ pound

↠ pow

↠ pulse

↠ purr

↠ rap

↠ rattle

↠ ring

↠ ripple

↠ roar

↠ rumble

↠ rustle

↠ scream

↠ screech

↠ scrunch

↠ shriek

↠ sizzle

↠ slam

↠ snap

↠ snarl

↠ snort

↠ splash

↠ sputter

↠ squak

↠ squeal

↠ squeek

↠ squish

↠ stamp

↠ swish

↠ swoosh

↠ tap

↠ tear

↠ throb

↠ thud

↠ thump

↠ thunder

↠ tick

↠ tinkle

↠ toot

↠ trill

↠ twang

↠ twitter

↠ wail

↠ wheeze

↠ whine

↠ whisper

↠ yap

↠ yelp

↠ zap

#writing#writing tips#story ideas#reference#knowledge#writing reference#vocabulary#synonyms#writing help#writing words#writing fiction#writing inspiration#writing advice#senses#creative writing

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vocabulary List for Kiss Scenes

Ways to Kiss

gently

softly

lovingly

affectionately

tenderly

briefly

quickly

passionately

seductively

sensually

sincerely

slowly

frantically

shamelessly

Adjectives for Kisses

amazing

wonderful

memorable

loving sweet

tender

innocent

warm

romantic

lingering

spicy

breathtaking

seductive

affectionate

dreadful

terrible

awful

wet

sloppy

soft

moist

slobbering

drunken

clumsy

uncomfortable

awkward

passionless

Verbs for Kiss Scenes

pulse

flare

overwhelm

stun

stagger

flutter

coax

encourage

brush

bite

nip

nibble

taste

feast

savor

devour

delve

explore

worship

fuse

drown

invade

capture

imprison

swirl

massage

cuddle

caress

cup

pet

rub

trace

skim

trail

graze

hiss

growl

murmur

come apart

Nouns for Kiss Scenes

flavor

tang

embrace

sensation

ectasy

rush

greed

frenzy

euphoria

elation

rpture

jolt

rhythm

velvet

goosebumps

lobe

nape

mess

Types of Kisses +

a song

a smooch

a peck

french kiss

single lip kiss

lizzy kiss

ice kiss

lip trace kiss

butterfly kiss

air kiss

eskimo kiss

hickey

lovebite

If you like my blog, buy me a coffee☕ and find me on instagram! 📸

References

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/relationships/love-sex/how-to-kiss-in-7-different-ways/articleshow/55049549.cms

https://www.wattpad.com/408233278-vocabulary-word-lists-for-writers-words-for-love/page/6

http://getintoenglish.com/they-smooched-on-the-balcony-kissing-vocabulary/

#writer#writers#creative writing#writing#writing community#writers of tumblr#creative writers#writing inspiration#writeblr#writing tips#writers corner#writers community#poets and writers#writing advice#writing resources#writers on tumblr#writers and poets#helping writers#writing help#writing tips and tricks#how to write#writing life#let's write#resources for writers#references for writers#writers block#writerscommunity#writer stuff#romance#vocabulary

409 notes

·

View notes

Text

Descriptive words for the exoskeletons of ants:

striate - with many parallel grooves

tuberculate - with little protrusions covering the surface

reticulate - split into irregular cells

opaque - light cannot pass through

translucent - light can pass through

shiny - reflects light, has visible reflections on the surface

matte - textured to absorb and prevent visible reflections.

glabrous - smooth

punctate/foveolate - covered in little round depressions

rugulose - wrinkled

pilosity - the degree of pilosity refers to how hairy the ant is

reclinate hairs - hairs that lay flat

tomentum - wooly hairs

clavate hairs - hairs that are club-shaped

#ants#vocabulary#ant vocabulary#descriptive words#exoskeletons#myrmecology#antposting#insects#bugblr#bugs#invertebrates#antblr#entomology

440 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wild vs. Feral, Domesticated vs. Tame, Native vs. Invasive, and Why Words Matter

Originally posted on my website at https://rebeccalexa.com/wild-vs-feral/

Recently a post crossed my dash on Facebook featuring a small group of llamas in the forests of the Olympic Peninsula. The caption described them as “wild” llamas (Lama glama). That may seem pretty innocuous to the average person, but to a naturalist it’s a gross mischaracterization. For one thing, llamas are completely domestic animals, no more wild than a cow or dog; they are descended from the guanaco (Lama guanacoe), which is a truly wild camelid. So this means that the llamas on the peninsula are feral, not wild. But why does the distinction of wild vs. feral matter so much?

The terms we use to describe various species help us to understand their origin and, perhaps more importantly, their current ecological status. These concepts aren’t just relevant to scientists, however. Everyday people are constantly making decisions that can affect the ecosystems around them, and often these decisions are made without having a full understanding of their impact.

For example, look at how many people release unwanted pets into the wild, whether domesticated rabbits, goldfish, snakes, or other, more exotic animals. Some of these unfortunate animals end up dying pretty awful deaths due to starvation, exposure, or predation. But others manage to survive and reproduce, becoming the latest population of non-native–and potentially invasive–species in their ecosystem. This wouldn’t happen if more people understood the impact of non-native species, and how releasing captive animals puts native species at risk.

But it all starts with knowing that there’s a difference, and understanding the terms that explain why that difference exists. So let’s explore some vocabulary that can be used to describe species, whether animal, plant, or otherwise.

Let’s start with domestication, because there often seems to be confusion as to what makes a species domesticated. Domestication is a process that takes many years, often measured in centuries. Humans breed chosen animals for particular traits over a number of generations. As time passes, each subsequent generation becomes more different from the wild species it originated from, and eventually a new, fully domesticated species emerges from this process of artificial selection by humans.

Dogs (Canis familiaris or Canis lupus familiaris) are the first animal humans domesticated in a process that started about 30,000 years ago. They evolved from the now-extinct Pleistocene wolf, a particular lineage of the gray wolf (Canis lupus), and it’s likely that the partnership began as some wolves showed less fear of humans while scavenging from our kills. By 14,000 years ago dogs were a distinct species (or subspecies) from wolves.

Dogs display very different characteristics from wolves. Their faces tend to be shorter with a more pronounced stop (the bump in the forehead where the muzzle meets the rest of the skull.) Floppy ears and curled tails are common, as are patchy-colored coats. Dogs tend to have weaker muscles than wolves of a similar size, shorter legs and smaller feet, smaller teeth, and a smaller size overall. This is a phenomenon known as neoteny, in which domesticated animals have a tendency to retain more juvenile physical traits of their parent wild species, and you can see it in domesticated animals across the board.

But it’s not just physical appearances that matter. Behaviorally dogs are generally more friendly toward humans; in fact, they’ve even developed some human-friendly body language that wolves don’t have, like “puppy dog eyes.” They can be easily trained and, unless poorly socialized, dogs generally enjoy the company of humans.

In many ways, physically and behaviorally, a dog is a wolf that never grew out of its puppy stage. While a young wolf pup may be able to live in someone’s house for a short time, as they grow older they become more destructive and less tolerant of human company. Your dog may love watching out the window during a car ride, but a wolf is going to be much more stressed out by the experience. Even wolf-dog hybrids have to be treated differently than your average domesticated dog because the wolf content has a significant effect on behavior.

This is just one example of how domestication isn’t just a matter of a few generations of selective breeding. You can also compare domesticated horses (Equus ferus caballus) with Przewalski’s horses (Equus ferus przewalskii or Equus przewalskii) or zebras (subgenus Hippotigris), domesticated cows (Bos taurus) with stories of fierce wild aurochs (Bos primigenius), and so forth. In every case the wild and domesticated counterparts are very different in both appearance and behavior.

Now, what about the term “tame”? Many wild animal species have been tamed over the years, either wild-caught individuals or those born in captivity. These tame animals may be more docile in comparison to their fully wild counterparts, but this generally takes a lot of handling and socialization from a young age. Moreover, tame animals retain a lot more wild behaviors than domesticated ones.

Take those supposed “domesticated” foxes that people want to have as pets. Most of the foxes available as pets have no relation to those in the famous Russian fox domestication experiment, but are from modern fur farm lines. And in fact the study foxes came from Russian fur farms, so the researchers were beginning with pre-tamed animals rather than truly wild ones. While some tame foxes may be more amenable to human handling than wild foxes, they are by no means domesticated. They are more prone to wild behaviors like urinating everywhere to mark territory, chewing on anything they can get their jaws on, nipping, and making a LOT of noise. Moreover, whereas dogs adapted to eating an omnivorous diet after millennia of eating alongside us, foxes need a more specialized diet than what you can get at a pet store.

Unfortunately there are unscrupulous people within the exotic pet trade who will advertise their tame (at best) stock as “domesticated.” This often leads consumers to thinking that they’re getting a much more tractable animal that will be as easy to care for as a cat or dog, and sets up everyone involved for disaster (except, of course, the seller with a fatter wallet.)

Next, let's compare wild vs. feral. A wild species is one that has never been domesticated, nor have its ancestors. Generally it will be a native species to its ecosystem, though non-native species can also be introduced to an ecosystem without ever having been domesticated. A feral animal, on the other hand, is a member of a domesticated species that has escaped or been released back into the wild and has survived to reproduce new generations that have never been handled by humans.

I’ve often heard people refer to the feral swine (Sus domesticus) that have ravaged ecosystems worldwide as “wild pigs”. They may behave in a wild manner, and they certainly look rougher and hairier than your average well-fed domesticated pig on a farm. It’s not uncommon for feral animals to regain some traits of their wild ancestors. However, that does not make them truly wild.

If you manage to wrest away a litter of newborn piglets from a feral sow and bottle-feed them, they are likely to be able to be socialized and kept in captivity, though they may still physically resemble feral pigs. They haven’t lost the deeply-ingrained genes that carry domesticated traits. However, if you try to raise a newborn Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa) or red river hog (Potamochoerus porcus), it will lack the domesticated traits of its farm cousins and show more wild traits as it ages, making it a rather unsuitable pet or farm animal. We also see this return to domestic traits in mustangs and other feral horses captured at a young age. While a mustang born in the wild may be tougher to work with at first than a foal born in captivity and handled from birth, the mustang will be much more calm and easier to train than, say, a zebra.

The problem with referring to feral animals as “wild” is that this suggests they are a natural part of the ecosystem they are in. Because a truly domesticated species (or subspecies) is not the same as the parent species, it has no place to which it is native as a wild animal.

A native species is one that has evolved in a given ecosystem for thousands or even millions of years. In the process it has developed numerous intricate interrelationships with many other species in that ecosystem, creating a careful system of checks and balances. A non-native species is any species that has been taken out of the ecosystem in which it evolved and placed in a different ecosystem where it is not normally found.

For example, here in North America the mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) is a wild native species. While it may resemble domesticated pigeons, it has never been domesticated even when kept in captivity. The Eurasian collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto), on the other hand, was introduced to the Americas after a few dozen individuals were released in the Bahamas in 1974. The feral pigeon (Columba livia domestica) is a domesticated species derived from the rock dove (Columba livia), which is native to Europe, west Asia, and northern Africa. Both the collared dove and pigeon are examples of non-native species. Most non-native species do not offer any benefits to the ecosystems they are introduced to because they do not have established relationships with native species. When they compete with native species for resources, they weaken the ecosystem overall.

Non-native species can be further categorized as naturalized or invasive, or even both. A naturalized species is a non-native one that has managed to establish reproducing populations, rather than going extinct without becoming established. Unfortunately, some people take this to mean that the species has become fully integrated into the new ecosystem. However, this is a process that again takes thousands to millions of years as other species adapt to the newcomer, which itself often also changes as it adapts to its new environment.

Ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) are an example of a naturalized species in North America. Native to Asia and parts of Europe, they were introduced here as a game bird 250 years ago. While captive pheasants are regularly released into the wild to offer more hunting opportunities to humans, this species has likely been naturalized from its first introduction.

Again, “naturalized” doesn’t mean “natural”. Pheasants compete with native birds like northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus) and prairie chickens (Tympanuchus spp.) Not only do they compete for food, nesting sites, and other resources, but they also spread diseases to native birds. Pheasants even engage in brood parasitism, laying their eggs in native birds’ nests and sometimes causing the native birds to abandon the nest and their own young entirely.

This means that the pheasants are also invasive as well as naturalized. Invasive species are non-natives that aggressively compete with, and sometimes displace or extirpate, native species. There are several hundred species that have become seriously invasive here, including both vertebrate and invertebrate animals, and numerous plants. But even the rest of the over 6000 non-native species that have become naturalized here still put pressure on native species, and have the potential to become invasive if their impact increases to a more damaging point.

Hopefully this gives you a clearer understanding of what these terms mean and why it’s important to know the difference. By knowing a little more about how your local ecosystem works and how different species may be contributing to or detracting from its overall health, you have more power to be able to make decisions that can preserve native species and help ecosystems be more resilient. Given that the removal of invasive species is one of the most important ways we can help ecosystems thrive in spite of climate change, it’s more important than ever that we increase nature literacy among the general populace. Consider this article just one small way to move that effort along.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#wildlife#animals#nature#biology#science#scicomm#invasive species#wild animals#domesticated fox#feral hogs#long post#vocabulary#ecology#educational#biodiversity#conservation#environment#environmentalism#climate change#pigeons

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

#words#words words words#vocabulary#books and libraries#bookworm#books and reading#bookstore#books & libraries#booklr#bookblr#reading#dark academia#light academia#chaotic academia#classic academia#book quotes#book#commonplace

173 notes

·

View notes