#tune in

Text

A BEATLE DIDN’T SAY THAT! Lewisohn’s lab-created quotes

“One of the things about this book that is a strength is it’s not me saying anything, it’s them or other people. I shape the text, I plot where it goes, I weave it, but the quotes are theirs. And so when I’ve got Paul McCartney behaving in a way some readers might think, ‘Whatever, oh dear,’ it’s actually him saying it. So you end up thinking that to his own credit he said that. It’s not me saying it.” (Mark Lewisohn, ‘Noted,’ (October 7, 2013) Somerset, Guy.)

This is hella long, and that's because it's actually a full blog post. (In case you want it in a less monstrous form.)

A lot of people for a long time have put a lot of trust in Mark Lewisohn’s footnotes. Or at least in the fact of those footnotes. Because once you dig through them for any length of time you quickly discover that Mark Lewisohn’s footnotes hold secrets that would get him expelled from any undergraduate program. They reveal a “history” often contrived through a mass of Frankenquotes, ala carte creations, Lewisohn rephrased ‘paraphrases,’ and worse. For some parts of the narrative things aren’t too bad, yet in others monsters lurk around every corner. But this is not the sort of thing that’s graded on a curve, and it is past time to have a conversation about what standards should be accepted in Beatles’ scholarship.

Lewisohn lists his sources unlike most others. And his footnotes alone are more insightful than some other writers’ books. (Reddit, r/beatles)

I do not judge footnotes based on their insightfulness, nor do I want to single out a redditor, but I grabbed the comment because it’s an opinion that is widely shared and even accepted as canon. At least by people who have not combed those freakish footnotes. And while the pages of piled up sources do look fearsome en masse, a closer inspection reveals an offense to the truth, a threat to the record, and a blight on Beatles’ historiography.

“The rules for writing history are obvious. Who does not perceive that its chief law is never to dare say anything false, and never dare withhold anything true? The slightest suspicion of hatred or favor must be avoided. That such should be the foundations is known to all; the materials with which the building will be raised consist of facts and words.” –Cicero

A Look at Lewisohn’s Lab-created Frankenquotes

FIRST, WHAT ARE QUOTES? AND WHY ARE QUOTES?

Quotes are the soul and center of recorded—and recording— history.

And the rules around quotes and quotation marks are pretty simple. Most people, even if they’ve never written anything beyond a term paper, understand what quotation marks represent.

A set of quotation marks means, “This person said or wrote ‘these exact words’ at some given time.” You can smash a quote from two hours before or two years before right up against a separate quote to make your point—although it might get your grade lowered—but what you cannot do is take two different statements from two different times and make them seem like they are one statement.

When you put words inside one set of quotation marks you are stating, in black and white, that the identified person made this statement. That they said all those words together—or if you want to excise a reasonable part and use ellipses to represent that— as part of the same statement.

Look, combining two separate quotes that are not part of the same thought or topic is not a subjective issue. It is not an issue of controversy. Quotes are the bone marrow of written history. Quotes are the alpha and omega. In academic work or journalism they have to be, which makes sense as soon as you think about it. If it was cool for me to take a transcript and grab half a sentence from page 2 and half a sentence from page 17, push them together as if those words were spoken one after the other in a single thought, I bet I can manage to get those words to say almost anything I want.

Separate thoughts must be in two separate quotation marks. Separate. Somewhere between four sentences and a paragraph is widely accepted as the “two separate quotes” line, and there can be some ethical and technical wiggle room in a long rant by a person, but what makes all that subjective nonsense go out the window is if the quotes come from two separate questions. Or two separate days. That’s two quotes. Not hard.

Which again, makes sense if the point is conveying information to the reader and lessening the chance of a writer manipulating someone else’s words to express something that the person didn’t mean.

This is the contract inherent in a quote. These are the rules we all agree to and understand, and these are the reasons why. And there’s no reason to break them.

Why do you want me to believe that John said these two things at one time? What was wrong with what he did say?

THE FOUR MOST COMMON WAYS MARK LEWISOHN MAULS THE MEANING OF THE QUOTE:

The Basic Lewisohn Frankenquote 🧟♂️

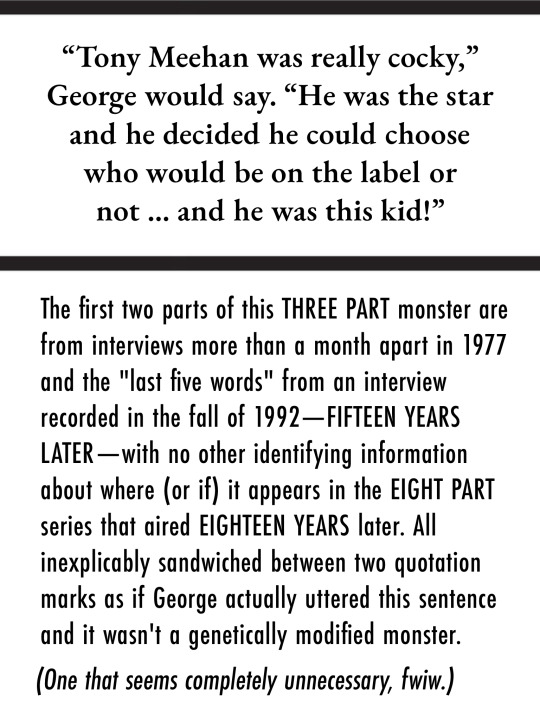

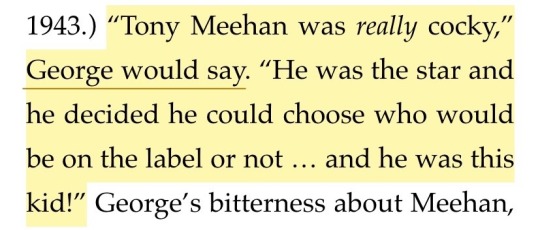

(“CONCLUDING FIVE WORDS FROM—” – I cannot even see the point of this THREE PART monster. Full footnote reads: 9) Author interview with Tony Meehan, September 6, 1995. (“I met George again in 1968 and for some reason he was harboring a grudge against me. He was very, very uptight about it—’You blocked us getting a recording contract …’ ”) First part of George quote from interview by Terry David Mulligan, The Great Canadian Gold Rush, CBC radio, May 30 and June 6, 1977; concluding five words from interview for The Beatles Anthology)

This three-headed monster attributed to George Harrison is a very dull little guy. Not particularly venomous. Just convenient, I guess. For whatever reason, Mark Lewisohn decided it was worth rummaging through the quote buffet until he collected enough pieces for George Harrison to say this thing. “…concluding five words from…” What are we even doing here? No, really. Please tell me.

And like a lot of the footnotes for these bespoke quotations, there are further problems. “[F]rom interview for Beatles Anthology”? An interview that aired? In one of the episodes? Can you narrow it down? I guess I’ll just have to listen very closely to them all and hope I don’t miss the five words.

But if we got bogged down in the sorts of trivial details that would immediately lose a college student a letter grade off a History 101 paper we would never get anywhere. We have to stick to the violent felonies.

*Love the "George would say——" Uh, would he? Well, I guess after all that trouble you went to, he would now. It's really incredible how cavalier Lewisohn is about a Beatle's words.

These sorts of reconstituted, lab-engineered, made up “quotes” are shot throughout Tune In. “Quotes” made up of words from two, three, and even four sources, spoken months or often years apart.

Ala Carte Creations 🍱

It really is a buffet, and these ala carte creations come in all shapes and sizes. They might just be words that have been plucked up and glued back together to make something more useful to a particular narrative. (Ellipses or dash optional.)

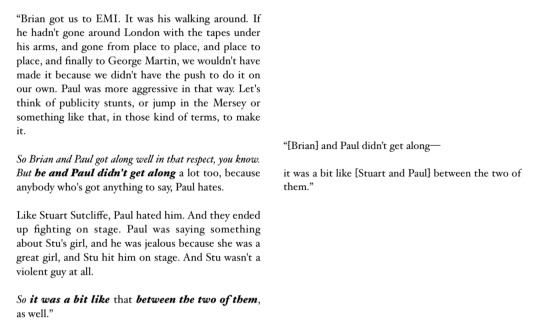

TUNE IN: “John saw a bigger picture, and it would be surprising if it wasn’t equally obvious, or made obvious, to Brian and George. He likened Paul’s enduring snag with Brian to his other long-standing difficulty: ‘[Brian] and Paul didn’t get along—it was a bit like [Stuart and Paul] between the two of them.’” (Footnote 37: Interview by Peter McCabe and Robert D. Schonfeld, September 1971)

Bonus 🍒 Phoebe's dramatic reading of John's original quote:

The Donut 🍩

Then there are a seemingly uncountable number of “quotes” with a sentence or three ripped out from the middle, but with zero representation that more words were ever there. (And in most of these particular deceptions, the simple representation of something excised (. . .) would make the quote fine. There are a lot of these, but they are also the easiest to fix.)

Chapter 10: “I was in a sort of blind rage for two years. [I was e]ither drunk or fighting. **It had been the same with other girlfriends I’d had.** There was something the matter with me.”

And then there are the true buffet bonanzas, words lifted and twisted beyond recognition until they say something brand spanking new.

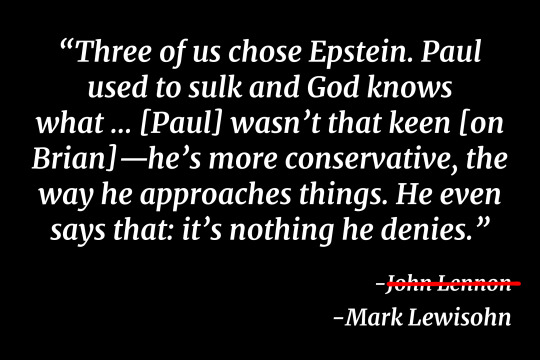

However, John remembered Paul’s attitude to Brian being very different. John was always emphatic that Paul didn’t want Brian as the Beatles’ manager and presented obstacles to destabilize him, to make his job difficult … like turning up late for meetings. “Three of us chose Epstein. Paul used to sulk and God knows what … [Paul] wasn’t that keen [on Brian]—he’s more conservative, the way he approaches things. He even says that: it’s nothing he denies.”

The Lewisohn Remixes 🍸

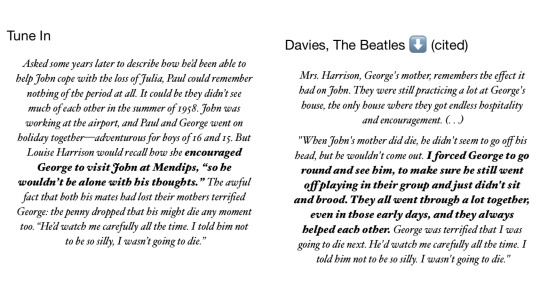

And then there are the “paraphrases.” I couldn’t even begin to guess how many of these there are, and often they aren’t even paraphrases, but whole new Mark Lewisohn re-interpretations with quotation marks slapped around them. But if you don’t check, you probably won’t know, because like this Lewisohn rewrite of a well-known Mrs. Harrison quote, there’s a good chance you’ll recognize the bulk of it, making it less likely that you’ll catch the scalpel work excising Paul. And while I don’t want to get caught in the nooks and crannies of intent in an example like this one I have to say, just this once, that what has to be a purposeful excising of Paul to create a slightly new quote on one side, combined with a badly acted, bad faith—(or bad scholar)—“Where was Paul when John’s mom died?” on the other, is par for the course.

George Harrison’s mom’s made up Lewisohn rephrase which coincidentally removes Paul from the imagery.] ❦ LEWISOHN:“ Asked some years later to describe how he’d been able to help John cope with the loss of Julia, Paul could remember nothing of the period at all. It could be they didn’t see much of each other in the summer of 1958. John was working at the airport, and Paul and George went on holiday together—adventurous for boys of 16 and 15. But Louise Harrison would recall how she encouraged George to visit John at Mendips, “so he wouldn’t be alone with his thoughts.” ❦ DAVIES: “They were still practicing a lot at George’s house, the only house where they got endless hospitality and encouragement. . . . I forced George to go round and see him, to make sure he still went off playing in their group and just didn’t sit and brood. They all went through a lot together, even in those early days, and they always helped each other.”

Why do you have to slice and dice and reconstitute people’s words? No writer, and certainly no historian, should ever feel empowered to take words from a historical figure from two or three different places and topics and times, splice them together, and tell us, “Winston Churchill said this.” No he didn’t! Why are you so intent on changing the words of the people you’re writing about? What’s wrong with just using two different quotes?

You cannot take two or three quotes from two or three or even four separate statements, stick them between one set of quotation marks and say John or Paul or George or Joe Smith said this.

No they didn’t. They never said that. Why do you want me to think they did??

All these words are Abraham Lincoln’s, but this is not a Lincoln quote:

“Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of — making a most discreditable exhibition of myself.”

(I kept it ridiculous, although I didn’t have to.)

But I want you, the reader, to be saying to yourself, “Okay, enough already. I get it!” Because in the last few days I have wandered too far into the weeds too many times and written far too many words detailing the multiplicity of ways Mr. Lewisohn does violence to each and every law of reporting historical facts, and could write many more. And I will post a more detailed list of the crimes against the quote that I am charging Mark Lewisohn with as we go forward, but I don’t think we need that now. The fact is that every fair-minded person knows what quotation marks represent, and there is no more fair-minded group of people than serious Beatles fans and scholars. And it is those fair-minded scholars who I want most to hear me. Whether you’ve written books or host a podcast or just know that you know a whole lot of stuff and take seriously your part of the trust in preserving the truth about The Beatles for us and future generations, it is you I am really talking to. My Cicero quoting-freaks. The ones who care about getting it right.

“The chief, the only, aim of style is to put facts in a clear light, with no concealment.”

- Lucian of Samosata

What footnotes can do, and what footnotes can’t.

You can list multiple sources in a single footnote. That’s not only fine, it’s correct. If I want to tell part of a story based on several sources, that often means several sources in a footnote. But not for one, single quote.

The problem isn’t the footnote, it’s the bioengineered quote on the page that you swept under a footnote hoping I wouldn’t notice.

Which leads us to what a footnote is not. A footnote is not a post-hoc fixative for your textual sins. You cannot do whatever you want as long as you confess it in a footnote. A footnote is not a magic spell. A footnote is not the universally understood symbol for “I have my fingers crossed behind my back.” You cannot fix lies and misrepresentations in the footnotes. Footnotes aren’t for trying to chase down three different sources to match up which part of a manufactured “quote” someone said on which date. Footnotes are not the picture on the front of a puzzle box. I should not need to find corner pieces to figure out which of these George Harrison words were actually spoken together.

Footnotes are a truthful and independently verifiable record of primary sources. It’s that simple.

And taking Mark Lewisohn completely out of the picture for a moment, I feel sure we can all agree that neither John Lennon nor Paul McCartney nor George Harrison nor Ritchie Starkey would want anyone rearranging their words as if they were guitar chords. You wouldn’t take three-quarters of Penny Lane and one-quarter of Across the Universe, put them together and call it a Beatles‘ song. So don’t take three quarters of John to Jann Wenner and one-quarter of John to Lisa Robinson, put them together and call it a Beatle’s quote.

MY PERSONAL STANDARD IS THAT IF SOMEONE REPRESENTS, “A BEATLE SAID THIS,” IT BETTER DAMN WELL BE SOMETHING A BEATLE SAID.

None of the Beatles, dead or alive, would be cool with their words being taken out of context at all, let alone two or three different statements on god knows what being combined into one. This isn’t hard, though. Use two or three separate quotation marks, and don’t take statements out of context. Don’t mix and match their words, but don’t twist them, either. If a person said something, it is the historian’s duty to represent those words to the best of your ability, and then use them to tell a factual story focused on what you feel is important. Staying true to the original words and true to their meaning. If you can’t use those words without twisting them, then change your story to fit their words, not the other way around. If their statement helps tell the story your way, use it! For goodness sake, John Lennon said at least two opposing things about almost every topic on earth, so there should be enough to choose from without being deceptive. I actually want the truth. Don’t you?

Biography is story based around accurately represented, trustworthy and verifiable facts. And look, Beatles fans, whoever your favorite is: we are not going to get the truth about his history if we don’t learn to take these things seriously. Let’s have—if not high standards—at least the lowest generally accepted standards. In the mid-term we need a lot more Beatles scholars with a lot more points of view, and now—right now—we need experienced Beatles scholars to prioritize searching out and finding smart, interested people to mentor. And we simply must ensure that we aren’t allowing to solidify into stone “facts” that are not facts and statements no one ever made. I don’t think any honest Beatles fan—(which rounds up to all of them)—wants any question around that issue.

The record is the most important thing. Now, and always. This is not about John versus Paul. John versus Paul may live on always in our hearts, but for Beatles history, it’s the wrong question. I’d rather someone be up front about their loves, but in the end the focus should be on representing the primary facts in their most pristine form. Love who you love most, but place truth above all. Pristine facts. Pristine quotes. Nothing hidden. Nothing misrepresented.

Let the historical actors speak for themselves. That is their right.

And the historian’s duty.

NEXT, WE DISSECT A MONSTER.

Final note: I became frustrated and (maybe strangely) offended by Lewisohn's obscene pretenses in 2020, but my frustrations were nebulous and unfocused until this incredible AKOM series. I feel much better now. Angrier. But better. They worked their asses off. 🥂

#lewisohn#akom#the beatles#tune in#fine tuning#frankenquotes#lewisohn's monsters#historiography#paul mccartney#john lennon#george harrison#ringo starr#mark lewisohn#a beatle never said that#beatles#brian epstein#allen klein#Spotify

161 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things Fall Apart continues tomorrow

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘John fascinated me the most because he exuded rocker,’ says Jürgen [Vollmer]. ‘I was a little disappointed when later I got to know him because he was a softie, but he carried off the rocker image perfectly. At the time, though, I never felt comfortable in his presence.’

Tune In by Mark Lewisohn.

Love that he was uncomfortable, until he was disappointed.

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a fun collection of quotes from the Let It Be Beatles Interview with Mark Lewisohn conducted on August 20, 2018. This is mostly for @mythserene's enjoyment, but it's also a fun lil supplement to this comment by @talking-perfectly-loud on a post by @anotherkindofmindpod, which includes some revealing, deeply salty quotes by Lewisohn from an episode of Nothing Is Real.

The below soundbites focus on Lewisohn's feelings towards the Harrison estate, particularly Olivia, though Lewisohn also lets us know that he considered suing George at one point. Italics used to indicate tone; bold font is added emphasis by me.

This is from ~1hr8min into the interview, after a discussion of Mal Evans diaries. Here's a partial transcript:

"No, no, Olivia Harrison doesn't want anything to do with me at all. Yeah, so it's very frustrating because I just want to make the history better and better and better and more and more correct, especially more and more correct in terms of balance on all four Beatles, but whatever."

This is a longer clip (6:26) from ~1hr23min in the original interview. They're discussing Lewisohn's falling out with Apple/the Beatles/George in particularly, which came about because he was falsely accused of bootlegging, or something like that. He's told a few variations of this story.

The first 3ish minutes give some flavor and backstory. Some choice quotes (they're at about 2:50, 4:35, and 5:42 in this clip):

“To the day he died, George blocked me, and Olivia blocks me in George’s name, and so it still carries on.”

“I’ve never, ever leaked, and that was why it was so galling to be accused of being a bootlegger. George Harrison accused me of being a bootlegger to my face in front of a whole film crew, the bastard. I mean, really. A horrible, horrible thing to do. I really should have done him for slander, and in fact at one point I was tempted, believe it or not. Because, you know, I’m a professional, I’m on a shoot, I’ve got a whole unit with me, and he’s accusing me of being a bootlegger in front of everybody, which was- he had no evidence for because there wasn’t any, but that didn’t matter. He was accusing me without evidence, and it was wrong, and um, you just have to put up with these things. These people, they can get away with murder. Celebrities, you know?”

Lest we think George was wilding out solely because of the bootlegging, Lewisohn helpfully clarifies that it was also Paul's Fault:

“The irony of that was that I actually had started off really well with George. I knew George from ’87, personally, and we’d had nice times, and it was- one of the things that flipped it was when I began working regularly for Paul.”

This was the part of the podcast that really took me aback, from around the 1hr43min mark. There's some chatter about Let It Be (the film), and then Lewisohn goes off once again about Olivia Harrison. He's quite impassioned, and then seems to make a conscious effort to talk himself down.

“I don’t know Olivia Harrison. I’ve never met her, which makes her- just- [angry] blocking of everything I do so ridiculous, because she doesn’t even know me. But if, as it would appear, she’s taken it upon herself to perpetuate George’s wishes, which is something that you might expect a spouse to do when their partner’s died, if the partner says, ‘Don’t ever allow this’, then she would take it as her duty not to allow it.”

This is followed by some hedging.

There are several other choice tidbits in this two hour Lewisohn marathon, but Olivia Harrison was foremost in his mind. But don't worry, guys, he's not biased!

#george harrison's last words were fuck mark lewisohn. hare krishna#CONFIRMED#olivia harrison get behind me#next substantiative post coming soon#just a bit of fun for now~#mark lewisohn#tune in#lewi-sins

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

“[August 1960, the morning of the Beatles' departure for Hamburg] In Allerton, at 20 Forthlin Road, Jim Mac ensured his son had enough cod liver oil capsules for two months, and enquired (as he did most mornings) whether the boy’s bowels had moved, then he gave him an Englishman’s pep talk, making him promise to be a good lad, stay out of trouble, eat proper meals and write often.”

– Mark Lewisohn in The Beatles – All These Years – Extended Edition: Volume One: Tune In (Chapter 19)

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

buckhead1111

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

The chapter of Royston Ellis meeting the Beatles is so wild.

He first hits on George at the Jacaranda. George responds to this with a casual “oh, you’d love my friends” and brings him to Gambier Terrace:

Also dropping into the Gambier Terrace pit was a special guest, Royston Ellis, “King of the Beatniks.” The bearded bard, who featured in TV documentaries and press articles whenever an offbeat teenage angle was needed, was in Liverpool to read his poetry at the university on June 24/25, and he swiftly found himself drawn into the Beatles’ company. The conduit was George, who (with nothing else to do while John, Stu and Paul were in school) was hanging around the Jac when the wandering coffee-bar poet traipsed in, drawn by hip radar to “the happening place.” Avowedly “trying everything,” Ellis was an active bisexual in this period of his life and he took an immediate fancy to George: “He looked fabulous with his long hair and matelot-style striped T-shirt, very modern, which is why I deliberately spoke to him. I was nineteen and he was seventeen and we clicked right away.”15

George took Ellis, his typewriter and his duffel bag back to Gambier Terrace to meet John and Stu. A rapport was quickly established and Ellis was invited to “crash” for a few days—yet another occupant for the filthy back room.

Then Ellis hits it off with John and Stu and wants them as a backing band:

Ellis says he developed a particular rapport with John and Stuart and that they discussed poetry, art and London. When he left, they spoke of doing it again sometime: “We were talking about how I wanted a band to come to London and back me on my Rocketry performances, and they were thrilled at the idea.” Art school studies finished the following Friday, July 1, marking the end of Stu’s fourth year and John’s third and last because the college was waving him goodbye. The exam results, when they came through on August 1, were just as expected: John failed and was out, Stuart passed the NDD, for which he received a certificate. The option was there for him to do a fifth year and attain the highest available qualification, the Art Teacher’s Diploma (ATD), akin to a degree and entitling him to become a teacher … but both he and John were pondering a period as prospectors, and doing something again with Ellis was a definite possibility.

So much so, Ellis is responsible for the first* two mentions of the band in the newspaper:

As for Ellis, so much was he enthused by the possibility of appearing with them again that he soon got the Beatles their first mention in a music paper. It was the July 9 edition of Record and Show Mirror, where a supercilious little article about “the bearded sage of the coffee bars” ended “he’s thinking of bringing down to London a Liverpool group which he considers is most in accord with his poetry. Name of the group? ‘The Beetles’”

….A born publicist, Royston Ellis knew how to manipulate a follow-up, writing a letter for publication that clarified a point in the first. He expressed his intention to find a group that would join him on TV appearances with Bert Weedon and the Shadows, and reiterated, “For some time I have been searching for a group to use regularly, and I feel that the ‘Beetles’ (most of them are Liverpool ex-art students) fill the bill.”

John and Stu decide to go to London on their own to join Ellis…but then chicken out:

By July 10, at the end of his three-year art school vacation, John had arrived at a key decision in his life: he would try to earn his living from the guitar. “I became a professional musician the day I got a red letter from the art college saying ‘Don’t bother coming back next September,’ ” he later said.31 Cyn would remember, “John decided that this [music] was very definitely the life for him. All the ideas that everyone else had for him of making an impact on the art world faded into the back of beyond with incredible rapidity, and with almost no regret at all. Aunt Mimi was distraught. Her view of his future couldn’t have been blacker at that time.”32

These events coinciding, it seems John and Stu decided to head south and hang out with Royston Ellis. Allan Williams is emphatic on the matter: he says John and Stu “split the Beatles and went down to London.”33 Norman Chapman would remember Stu asking him for a lift through the Mersey Tunnel one day so he (or he and John) could hitchhike to London—“They wanted to go down to London and become involved in this poetry-music scene.” Beat poets led a nomadic life by definition. Ellis lived for periods in all sorts of places, but his main base was still his parents’ house, at 31 Clonard Way, Hatch End, Pinner, Middlesex, a pleasant detached villa with the name Denecroft. This was the address he gave John while staying at Gambier Terrace. When Ellis arrived home one day his mother said he’d missed a visit from his “beatnik friends from Liverpool.” He never knew how many or who had come, but—as insane as it appears—John and Stu (and/or as Ellis always thought—hoped—George) had hitched the best part of two hundred miles, taken the trouble of locating his house in leafy Metroland, not stayed or left a message and then gone home again, never returning or making further contact. It makes no sense, but there it sits, illogical and incomplete.

Allan Williams remembers them being “back in Liverpool within a week, because it didn’t work out,” at which point the Beatles “reformed” as if they’d never been away. With bookings only every Saturday, it’s conceivable they did all this without missing one, and perhaps that was always the intention. However, while three independent witnesses (Ellis, Williams and Chapman) all remember something happening, none of the Beatles ever mentioned it—though in their interviews they talked with candor about everything. So it must remain in doubt, an intriguing puzzle unlikely to be solved.

There are two additional curiosities that may or may not be incidental. One is that, in the last days of July, a group of Liverpool art school students, apparently including John and Stu, went to London (or tried to go) to see a Picasso exhibition at the Tate Gallery. Second, and most fascinatingly, a set of photographs taken at this very time (mid-July 1960) in Stu and John’s studio-bedroom-slum at 3 Gambier Terrace includes several people they knew but not John and Stu themselves—perhaps because they were on the Hatch End trip. It was published on July 24 in the national Sunday rag the People in a sensation-splash headlined THIS IS THE BEATNIK HORROR. It’s as if a man on a flaming pie was pointing down at Flat 3, Hillary Mansions, Gambier Terrace, Liverpool 1. In six months, three Beatles moved in and the fourth was hanging out, the nation’s best-known beat poet had come here to get them high, and now, when a Fleet Street journalist and photographer were looking to substantiate a load of old tosh about dirty beatniks—reportage that could have been cooked up anywhere in the country—they landed in Stu and John’s room.34

Though hugely amusing, the feature had one unfortunate side-effect: because the address was given (a “three-roomed flat in decaying Gambier Terrace in Liverpool”) and some of the occupants (“well-educated youngsters”) were named, the landlord gave the tenant, Rod Murray, notice to quit. On August 15, everyone—Rod, Diz, Ducky, Stuart, John and sundry other bodies who’d joined them—would be out on the street.

—Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In, Ch 15 (May 31–Aug 15, 1960)

And Lewisohn is just like yup nothing to see.

So what the hell happened here? Was it just a school trip? Or was it a deliberate split?

#royston ellis#beat poetry#beatniks#tune in#1960#early liverpool#bug mysteries#i think about this once a week and just found the bit again#mine#mark lewisohn#reading tune in#prebugs#*i think they may have found an earlier mention since tune in printing#i have a june newspaper clip date in my timeline#john and stu#young george#june 1960#queer bugs#reading riding so high#joe mentions the dates of royston’s liverpool university appearance#june 24 1960 and davies says the first beetles mention in the newspaper is june 11#so theres some conflict there when was the first#just learned royston ellis died earlier this year#but kerouac website writers reached him in 2020 and he still claimed they got the BEAT ideat in the name from him#theyve got a clipping from june 5 with silver beetles#but lewisohn references a june 2 clipping with the A (beatles)#so thats too early for royston maybe they were deciding and flipflopping he helped settle on one i can see that#lalala i cant read its first mention in a music paper rather than a general newspaper

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the Beatles returned to Liverpool in December 1960 Stuart Sutcliffe had stayed on in Hamburg. He finally came home around the 15 January 1961 and took his place in the group a day or so later, ready to play the upcoming gigs at Lathom Hall.

The Beatles had all witnessed violence at venues in both Liverpool and Hamburg but the unfamiliar north end of the city around Seaforth was particularly rough. A lot of the Teds in the audience were likely to have worked on the local docks during the day and seemed to have a strong territorial mentality so the Beatles were often looking over their shoulders after a gig in case one of them had said the wrong thing or looked at the wrong girl, or John had done one of his great big winks, which delivered with just the right amount of sarcasm and provocation would really wind the Teds up.

They were right to be wary. Neil Aspinall, a friend of Pete Best who was just starting to drive The Beatles to gigs, and would eventually become their road manager would recall an incident at Lathom Hall in January 1961 where "two troublemakers followed Stu Sutcliffe into the dressing-room muttering things like ‘Get your hair cut, girl!’ John and Pete saw this and went after them. A fight broke out and John broke his little finger…It set crooked and never straightened.”

Pete Best: “When we’d done our session and came off, we changed, which didn’t take an awful lot of time because we basically played in what we stood up in. Stu went out, followed by John and myself.

These lads started a fight with Stu after picking on him. We got to know about it because some people ran back to the side of the stage where we had come from and said, ‘Stu’s getting the living daylights knocked out of him. So John and I dashed out. We threw a couple of punches, sorted things out and pulled Stu back in again. The fact that John and I had pitched in and got involved made (the teds) feel a certain amount of respect for us….as a result of the fight John broke a little finger. He still managed to play for a couple of gigs after that. He hadn’t complained …the next time we saw him he had a splint on it.

Neil had gone home to his studies while the Beatles were playing but when he returned to pick them up they told him "there's been a fight in the bogs". John had broken a finger, Pete had a black eye, Paul had been dancing around and Stuart had been kicked in the head. Apparently Stu had been trapped in the toilets by some Teds because their girls had been screaming, and John had probably done one of his big f*****g winks. (Tune In)

#:(#The Beatles#Stuart Sutcliffe#John Lennon#Pete Best#Neil Aspinall#quotes#John#Stuart#'John had broken a finger Pete had a black eye Paul had been dancing around and Stuart had been kicked in the head'#why'd they have to do Paul like that#Tune In#‘Get your hair cut girl!’ :(

57 notes

·

View notes

Note

What about 'Ask Your Mother'?

Oh I am so excited for this one! Another Dewey centric story! Basically the poor kid has questions and NONE of the adults wanna give him the answers for some reason

Here’s a snippet from the beginning:

#the journey I’m gonna make this poor kid on#will Dewey ever get the answers to his questions?#tune in#wip ask game#korkorali#writebackatya

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Really obsessed with the way Mark Lewisohn frames the Paris trip

John’s 21st birthday was a month away … his idea was to go away with Paul and enjoy it. Bob Wooler was party to their planning, and fought with them:

“They were bored, and decided they would go away for a month. I thought this was disastrous because they would be away from the scene too long and lose their fans. Fans were very capricious: they moved from one group to another. And anyway, what about the other two members, George Harrison and Pete Best? What about them, what do they do? We argued a lot about this …”

… all bookings from September 30 to October 15 had to be broken—an unpleasant job for Pete; he and George had to accept losing up to £50 apiece, as well as being left behind. John said George “was furious because he needed the money,” and it’s unlikely Paul extended George much sympathy …

… The promoters who paid the Beatles over-the-odds to present them every week had to “lump it” … they were incensed by it—but John and Paul hadn’t a care …

It was tough too on Dot and Cyn … That John was taking Paul, no one else, accentuates the renewed closeness since Stu quit the Beatles … [Bob Wooler said] “At times, they reminded me of those well-to-do Chicago lads Leopold and Loeb, who killed someone because they felt superior to him. Lennon and McCartney were ‘superior human beings.’”

-- MARK LEWISOHN, TUNE IN: THE BEATLES: ALL THESE YEARS (2013)

#NOT THE GAY SERIAL KILLERS COMPARISON!!!#i've read that quote before but i hadn't known the context until just now#can't stand mclennon....toxic duo of all time....#tune in#mark lewisohn#the beatles#mclennon#bob wooler#john lennon#paul mccartney

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

AKOM “Fine Tuning,” Episode 6: A prolonged jealousy

Another really excellent episode that I will have to listen to at least two more times to fully ingest, despite having lots of diffuse, unconnected notes where I ranted about most of the same text. They really backed up and gave it context and meaning, including adding a lot of things that I didn’t have and making sense of some of the extras that I did. It was both satisfying and frustrating: more satisfying than I expected, and my frustration feels more coherent and focused now.

I definitely think it’s one of the most important episodes.

There is only one point I would add, and that is just that when you listen to the episode it’s important to realize that Paul’s “jealousy” is the most egregiously non-sourced. There are basically two quotes that Mark Lewisohn uses to support this entire theme. The theme which he so beats into the ground that even if you don’t look at the footnotes it feels excessive.

I’ve mentioned before that when I read “Tune In” I was still very, very new to Beatles’ history. A newborn without any of the historiographical context, no understanding of the long, strange, John-deifying background, and therefore I wasn’t on the lookout for it. And that’s important because I went into the book with implicit trust, loved the writing, and still it was evident to me, fairly quickly, that I was reading an opinion column.

It was the cigarettes that did it

Paul’s care with money was noted—Pete says that while they all passed their ciggies around, Paul would “sneak one of his own to himself”—and he was still needling everyone about the Bambi sleeping arrangements, made all the worse now because he was jealous of Pete getting the best girls.

The second time I read the book I remember thinking, “Surely not that many people spontaneously bitched about Paul being stingy with cigarettes.” And that was my tipoff.

There are two quotes in the book about Paul and cigarettes that appear to be organic—one being Pete’s “sneak one of his own” quote in this episode—but you’d think that half the people Lewisohn talked to about their memories of some of the most famous people ever, and certainly the most famous from Liverpool, just magically thought that one of the most important things about these four guys was that Paul was stingy with cigarettes. And there is just no way that that is true.

But I also know how this works, inside out. You get “an angle” as a reporter. You have a story you want to tell, and then you interview people with that story—that angle—in mind. You ask questions that you think will elicit the responses that back up your thesis. And then, on the other side of the process, you filter the quotes you choose (and don’t choose) that tell the story you want to tell. And to be fair, every reporter and historian does this to some extent. It may just be to organize ideas in a coherent way, or it may be to focus on a theme. But it has also notoriously been used by historians to warp the truth and further a broader historical lie. (A very good example of this and the one closest to me is “the Dunning School” of the US Civil War and Reconstruction, the first real and condensed story of that conflict that injected into US historiography many complete lies, including the especially insane one that after the Civil War the “Radical Republicans” inflicted pain and humiliation on the South, which despite being the exact opposite of the truth is still the story most Americans “know.”)

Mark Lewisohn had a story he wanted to tell, and I believe that story is most obvious in his “jealous Paul” theme because it’s based on nearly thin air and even then is so ludicrously overblown. But I think it was just too tempting a canvas for Lewisohn. Setting up a dead, pretty kid as a sort of saint that Paul persecuted does so much work for everything else he wants to say about Paul, especially in the upcoming books. Hamburg becomes a pressure cooker where Paul’s true colors come out, and if Lewisohn can use Stu—a sort of perfect near-blank slate who never had time to put any of his memories into context—as a foil to Paul and to paint Paul as petty and jealous and seething, then all the rest of his work is easy. Stu is a layup that paves the way to seeing Paul as a bad guy. The concrete dries and everything else falls into place.

And look, there just is no way to see this theme as organic, because it’s not. It just isn’t. It’s not based on quotes or stories. There are a few completely disconnected quotes stretched to breaking that he uses to try to prop all this nonsense up with, but there is simply no defense for even 90% of the primary usage of them, and certainly not of the whole, big-picture story he creates with them.

I’m going to give one example—and there are many—but I admit to liking this one best because it’s all there in one passage based on one quote that doesn’t say any of this.

Passage:

But, as much as Paul liked exhibiting versatility, he was unhappy—he felt he’d been lumbered, that his multi-instrumental ability was tying him down. Who looked at the drummer? By rights, his place was out front, especially with his new guitar. Here he was, paying off the Solid 7 at ten bob a week and hardly getting to play it. Jealousy of Stu was stoked: Paul was in the back line while he remained out front (even if he was hiding and in dark glasses). One thing was for certain: Paul wasn’t going to abandon singing.

The only citation for all that Maca-inhabited resentment is the brief Paul quote already in the text, (FN35) and the next footnote—FN36—is from George on a new topid. There is no citation whatsoever to support any of Lewisohn’s finely-sketched fantasies of Paul’s vanity and jealousy.

FOOTNOTE 35: “I was drumming with my hands, playing the hi-hat and bass drum with my feet and I had a broomstick stuck between my thighs on the end of which was a little microphone, and I’m singing ‘Tell me what’d I say …’ It wasn’t easy!”

*Note: This quote is also in the text right under the ‘lumbered Paul wanted to be out front’ passage, so in some ways it’s an even thinner spread, if that’s possible.

So, according to Lewisohn:

Paul liked “exhibiting versatility” (a whole lot because of the modifier “as much as”)

Paul was unhappy because he felt “lumbered”

He felt he was being punished because he was TOO TALENTED

BY RIGHTS his place was out FRONT

He wanted to be LOOKED AT!

Jealousy of Stu is grabbed from thin air, based on nothing, and “stoked” by Lewisohn.

because, again, Stu was out FRONT

Did you catch the point that Paul is CHEAP?

Again, all of that is cited to this:

“I was drumming with my hands, playing the hi-hat and bass drum with my feet and I had a broomstick stuck between my thighs on the end of which was a little microphone, and I’m singing ‘Tell me what’d I say …’ It wasn’t easy!”

There are at least two more things that I want to say but this is long enough so I will put them off. (Hopefully not for long.) ✌🏻

#the beatles#akom#beatles#fine tuning#tune in#paul mccartney#john lennon#lewisohn#jealous paul#cherry picking#mark lewisohn#Spotify

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paul would claim, ‘I wasn’t brilliant at school, I was trouble at school. I used to get caned every frigging day. I was the class naughty boy . I was the one with long hair. I was the equivalent of John, in my school. And George was the other.’

Interview by Richard Williams, for The Times, 16 December 1981. Quoted in Tune In by Mark Lewisohn.

Paul 'No Seriously, I was a Rebel!' McCartney

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

@mythserene's fantastic exposé “A Beatle Didn’t Say That! Lewisohn’s Lab-Created Quotes” exposed several altered, sewn-together, and otherwise doctored quotes from Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In: The Beatles: All These Years (henceforth Tune In). I already had a less-than-favorable view of Lewisohn’s work after @anotherkindofmindpod's mammoth “Fine Tuning” series, a well-researched, often infuriating, always entertaining series that laid out the overarching bias in Tune In, but there can still be value in a biased work, particularly if you consume it with that bias in mind. Doctoring quotes, on the other hand--for a biography of supposed historical import, that's a capital offense. So how could a big-name author, revered for his rigor and devotion to primary sources, put so many barely-concealed doctored quotes into his work? Why would he do it? And if @mythserene could turn up several as part of an initial investigation, just how many of the quotes in Tune In weren’t actually quotes?

Naturally, I’ve chosen to do the sane thing, and check each of his sources, one by one.

I’ve started with David Sheff’s 1980 Playboy interview of John and Yoko, which Lewisohn cites 19 times in Tune In. Of these nineteen citations, sixteen are in some way altered, many in substantial, meaningful ways. I’m working on a longer post with side-by-side comparisons of all sixteen altered quotes, but that’s taking me aaaages to construct. In the meantime, here are two examples that illustrate some of the common ways Lewisohn alters source material.

A note on sources and notation: My numbering system for Tune In's footnotes is Chapter Number-Endnote Number, with "P" used for the prologue. My comparisons were made using All We Are Saying (David Sheff, 2000, St. Martin's Griffin, 229p). Page numbers are given as Sheff 2000. Lewisohn recommends the version of this book contemporaneously published in the UK by Sidgwick & Jackson as "the best available publication of this Q&A" (P-22). Onwards!

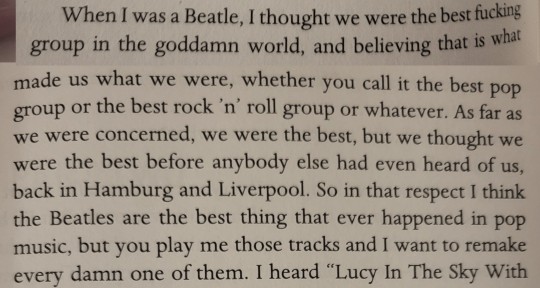

We will start at the end with the quote Lewisohn uses to close out Tune In (36-16). Sheff 2000 (p.72-73) on the top, Lewisohn on the bottom, commentary under a cut.

Highlighted in yellow are changes made by Lewisohn; in pink, a phrase of Lewisohn's invention. Hardly his most egregious work, but it demonstrates four common features you'll find in many of his altered quotes. They are:

First: The misleading use of the ellipsis. An ellipsis can be used to indicate text omitted from the original quote, but Lewisohn uses it here where there is no omission. He does the same thing with brackets in other quotes. This is one of the strangest patterns I've found while fact checking, and I can't figure out why he does it. Is it sloppiness? Or is he using notation that looks correct to give his work the semblance of academic credibility while distracting from parts of the quote he's actually changed?

Second: The pointless switcheroo of "the best rock 'n' roll group" and "the best pop group". Lewisohn frequently flips the order of words in a list, phrases in a sentence, or sentences in a larger quoted passage. Frequently, as here, this has no effect on the quote's meaning. It seems arbitrary.

Third: The glib closing line. I've found a few other examples of Lewisohn inventing a closing line to a quote that wraps up the meaning he wants the reader to take from it with a tidy bow. This line feels out of place, doesn't it? It's a little too tidy, a little too cheesy-dialogue-y.

Fourth: The tonal shift. This line comes from a larger exchange in the original interview where John discusses whether the Beatles will get back together, and what their musical legacy is. He seems proud of the Beatles, but he also seems conflicted, jaded, tormented by constant dissatisfaction with his musical/artistic output. Never satisfied. By adding his final line, Lewisohn turns an emotionally complex statement into the victory lap of a has-been, a high school quarterback reflecting on their glory days. It flattens John Lennon, and it's hardly the only example. Which brings us to...

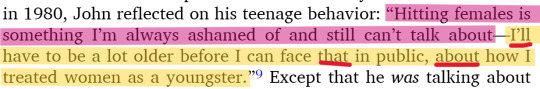

The quoted passage (found on Sheff 2000 p.182) is highlighted in yellow in both the source (above) and Tune In footnote 10-9 (below). In pink, Lewisohn's words, as attributed to John Lennon. Minor changes underlined in red.

This is one of the more well-known quotes in the Playboy 1980 interview, in which John discusses his past violent behavior, particularly his domestic abuse. I’ve included John’s whole answer because what Lewisohn chooses to omit here says as much as what he included/invented.

The changes to the yellow section are minor. The pink section is egregious. We have several sentences of John Lennon admitting to and reflecting on his violence against women, and Lewisohn distills that into “uwu hitting females bad, too sorry to talk about it.” It restates the section Lewisohn did quote, and it shrinks a major stride John took in taking some accountability for his actions.

I can see why Lewisohn would think saying less words, particularly less explicit words on this topic would make John look better, but it really doesn’t. Again, Lennon is flattened, stripped of his emotional complexity and his ability to meaningfully self-reflect.

Also, “females”? Really, Mark?

#mark lewisohn#tune in#the beatles#john lennon#i'm sorry this is so long i promise i don't have this much to say about every non-quote#lewi-sins

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Paul was also still getting together with John to write songs. Though their productivity seems to have slowed by autumn 1958, their ideas were merely branching out. Around October, perhaps during the half-term week at the end of the month, Paul made another visit to Mendips (‘John! Your little friend’s here again’) and was happy to find John typing a new poem. Actually, this one wasn’t a poem, it was more of a lunatic short story. Paul took one look and loved the wordplay, the typical Lennon phrases like ‘a cup of teeth’ and ‘in the early owls of the morecombe’. John called it ‘On Safairy With Whide Hunter’ and its origin was clear: it was from White Hunter, a TV adventure serial being shown by Granada, weekly yarns about ‘the surest and fastest shot in Africa’, overblown scripts brimming in bwana.

John let Paul join in and the satire became a way-out Lennon-McCartney Original.* Though some lines are characteristically John’s, especially the trademark renaming of the lead character every time he was mentioned (Whide Hunter is also Wipe Hudnose, Whide Hungry, Wheat Hoover and Whit Monday), others are probably Paul’s (‘Could be the Flying Docker on a case’ and also ‘No! but mable next week it will be my turn to beat the bus now standing at platforbe nine’). One imagines the two of them in stitches when they came up with lines like ‘All too soon they reached a cleaner in the jumble and set up cramp’. Another sentence – ‘Jumble Jim, whom shall remain nameless, was slowly but slowly asking his way through the underpants’ – could well have been a reference to Jim McCartney.

*Or as John put it, when it was part of a bestselling book six years later, ‘Written in conjugal with Paul’.”

– Mark Lewisohn in The Beatles – All These Years – Extended Edition: Volume One: Tune In (Chapter 14)

#I was looking through my ebook version of Tune In to check something for my fic#and stumbled across this#and it was so delightful i HAD to share#tune in#john#paul#jp#58#lennon-mccartney#ref

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

#feelings#problem#ignored#feedback#tune in#quotes#words#life lessons#wisdom#inspirational words#philosophy of life#life quotes#growth#healing#self knowledge

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

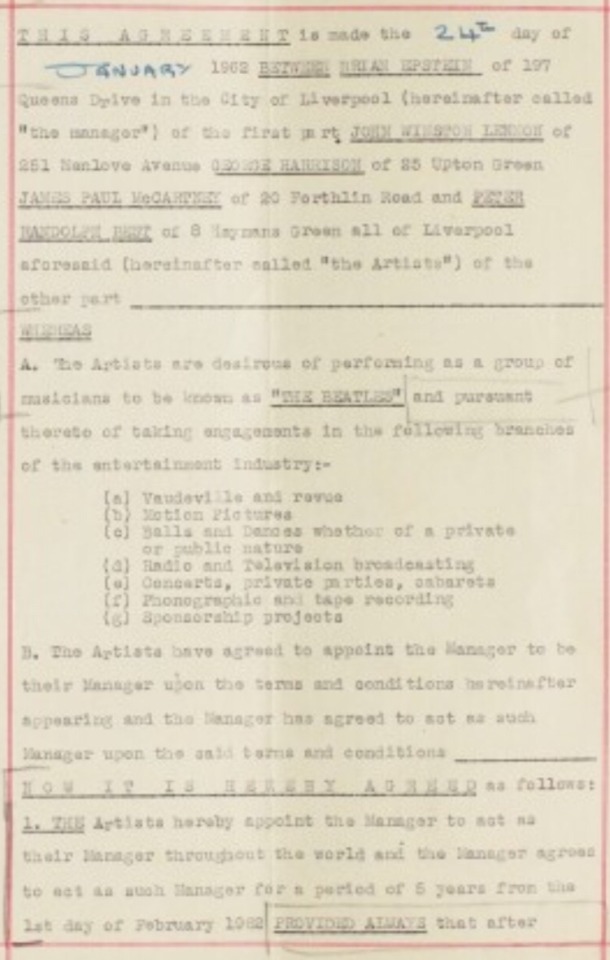

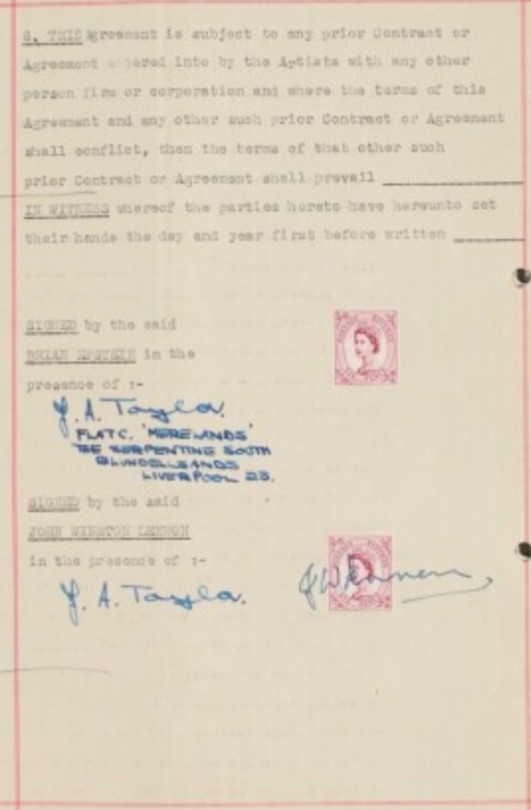

January 24, 1962: The Beatles sign their first contract with Brian Epstein

Paul then raised a late objection to Brian’s commission rate. The typed contract stated 10 percent, rising to 20 if their individual gross annual earnings exceeded £1,500, and Paul would later recall how his objection was based on the old tactic of holding out for less no matter what was being asked.

“He asked for 20 percent and I argued with him. I said, ‘Twenty, man? I thought managers only took 10 percent.’ He said, ‘No, it’s 20 these days.’ I said, ‘OK, maybe I’m not very modern.’”

It was a point on which Brian was prepared to concede. As signed, the contract has a penned amendment: 20 was crossed out and 15 written instead as the upper limit.

At 10 rising to 20 percent this would already have been a generous contract; at 10 rising to 15 it was a steal for the Beatles, and they’d no idea how much. It was standard for artists to pay two sets of commission, having not only a management contract but, separately an agency agreement; the managers took their cut for managing, agents took a further 10 percent for fixing all the paid work. Brian was shooting to do both jobs, providing the Beatles with this ambitious, all-inclusive service for the single 10–15 percent commission.

From Mark Lewisohn’s Tune In (Ch. 24) [x]

#the beatles#brian epstein#tune in#1962#mark lewisohn#management#contracts#negotiation#this is the first one they sign where brian doesnt#the next one is oct with ringo#but I think little changed#any wonder brian felt like paulwas the most difficult with this story??#early bugs#january#eppy and paul#text scans#Lewisohns point about Brian actually assuming two roles for the price of one is a real lightbulb#posting because I want to try to read it one day#the link allows you to zoom in but pages 4 and 5 are upside down#my first look was just trying to spot the amended portion but I don’t see anything crossed out??#looks like there’s a page missing between the first and the secon#reading tune in#also looking at johns signature it doesn’t look like he has the incorporated the mccartney E yet#hmm#mine

517 notes

·

View notes