#the first point is mainly directed at fans who like. for example find in-universe explanations for fucked up things authors write

Note

thoughts on evil Forrest 😈

We are going to start out by apologizing. This is very very late. I’m sure when you sent this ask, you meant it to be in the same joking tone that I approach all of my other propaganda posts. Sadly, this is actually going to be a deep dive into a few Evil Forrest related things, including the moment I feel they changed directions, the perfect wasted build-up, and the implications of the change/how it then negatively impacted the story. As I’m sure you already know, by being on my blog at all, I don’t think the story was good to begin with, so we are going to focus on the weird hoops they made themselves jump through to make that story still work. Additionally, I am only going to mention once, right now, how much of a waste it was to not have Forrest ‘fall for his mark’ and complete one of my absolute favorite tropes. Honestly, I think “because I want it” is a completely valid reason to like Evil Forrest. But, the question was “Thoughts on Evil Forrest” and these thoughts have been developing for over a year and a half. So, I apologize in advance.

The majority of this is under a cut, with highlights in the abstract. If no one wants to read this, I understand completely. Go ahead, skip it.

Note: it pains me greatly to not actually have full sources for this essay. Just know that in my heart I am using proper APA citations, I just absolutely do not feel like digging through tweets to find sources to properly cite.

Abstract:

Previous research indicates that Roswell New Mexico has a history of repeating excuses to explain mid-season changes to plots. This essay explores how those excuses are not only loads of crap, but how they hinder the show’s ability to tell a coherent story, misuse the multiple-plot structure to enhance the themes being explored, and lead to decisions that mean the show continuously goes over budget. This also means that characters are not used to their full potential and has led to what some fans consider to be “out of character” behaviors. While these behaviors are not universally agreed on, evidence can be shown that these behaviors directly contradict emotionally important character arc/plot points in the show.

The author of this paper acknowledges that the show took some strides to mend this problem. However, once again no consensus could be found on whether Forrest was a low-level member of Deep Sky and thus just allowed to fuck off on a bus, or his job was recruitment because he did a piss poor job of making Alex not join.

The concept of Evil Forrest has been with the fandom as early as New York Comic Con (NYCC) in 2019, when it was revealed that Alex had a new “blue-haired love interest”. Speculation abounded within the fandom, with some people, including the author, going “yeah, he’s evil” while others rejoiced in the concept of Alex having a loving partner. Speculation increased as fans discussed Tyler Blackburn’s seeming disinterest in his new love interest, prompting some once again to scream “EVIL” at the top of their lungs to anyone who would listen. Very little was revealed, beyond the fact that the new character would show up somewhere around episode 3 of the second season.

Episode 2.04 aired with some commenting on how he barely interacted with Alex- prompting more evil speculation- and others excited to see the characters interact more. The character appears again in 2.06, where he invites Alex to dubious spoken word poetry (which Alex attends); 2.08, where they have a paintball date and go to The Wild Pony; 2.10, where the two are seen writing together briefly at the beginning of the episode; and 2.13, where Alex performs his song at open mic night, tells Forrest his relationship with the person in the song was long over, and they kiss. Forrest was not revealed to be evil during season 2.

Amidst the season airing, Word of God via Twitter post announced that yes, Forrest had originally been planned as a villain, though not the main villain, but it was changed as filming progressed.

The Word of God Twitter post revealed that Forrest had originally been planned as a villain, but they decided that they could not make their “blue-haired gay man” a villain. This mirrors a similar situation and excuse used the previous season, where the character of Jenna Cameron was originally planned to work with Jesse Manes against the aliens, before it was changed because they just “loved Riley [the actress] too much”. Both of these examples occurred while already filming and reflect on a larger problem with the show. Though not the topic of this essay, it is important to note that both characters are white, both in the show and by virtue of being played by white actors. The fact that they couldn’t be villains for one reason or another is not a courtesy extended to the male villains who are all the most visibly brown, and thus ‘other’, members of the cast.

This also highlights the fact that, via Twitter, it has been revealed two other times that occurrences that were reported in season 1 also occurred in season 2. During the airing of episode 1.02, it was revealed that the single best build-up of tension in the show- when Alex walks to the Airstream not saying a word to Michael after a dramatic declaration- happened because one actor was sick at the time and they had to go back and film the kisses later. At the point of airing for episode 2.08, it was revealed that one of the actors were sick and unable to film a kissing scene. Allegedly, this caused the writers to retool the entire scene and deviate from the plan to make that subplot about Coming Out. The execution of this subplot will be explored later in this essay.

The last occurrence revealed via Twitter also revealed larger issues within the show: lack of planning and poor budgeting. During the airing of season 1, Tyler Blackburn was needed for an extra episode beyond his contracted 10. A full explanation was never given, but speculation about poor planning and to fill in because Heather Hemmens had to miss one of her 10 episodes due to scheduling conflicts for another project. During the airing of season 2, yet another tweet came out saying they made a mistake and Tyler would once again be in an additional episode. No explanations beyond “a mistake” were given, though once again speculation occurred. It is the opinion of the author that this was due to changing plot points over halfway through writing, while episodes were already in production. It has been speculated by some that these changes occurred during the writing of 2.08, which was being finished/pre-production was occurring roughly around the time of NYCC 2019.

Previous Literature:

A brief look at different theories of plots and subplots

Many people have written on the subject of plotting, for novels and screen alike. The author is more familiar with film writing than tv, but a lot of the concepts carry over. Largely, the B- and C- (and D- and E-… etc) plots should reinforce the theme of the A-plot. This can be through the use of a negative example, where the antithesis of the theme is explored to reinforce the theme presented by the A plot, or through other examples of the theme, generally on a small scale.

A movie example of this would be Hidden Figures (2016), where the A-plot explores how race and gender impact the main character (Katherine Johnson) in her new job. The B-plots explore the other characters navigating the same concepts in different settings and ways- learning a new skill as to not become obsolete and breaking boundaries there (Dorothy Vaugn) and being the first black woman to complete a specific degree program and the fight it took to get there (Mary Jackson). A TV example that utilizes this concept of plot and theme is the 911 shows. Each of the rescues in a given episode will directly relate to the overall theme of the episode and the overall plot for the focus character. This example is extremely blunt. It does not use any tools to hide the connection, to the point you can often guess the outcome for that A-plot fairly quickly.

This is not the only way to explore themes within visual media. Moonlight (2016) looks at three timestamps in the life of Chiron. Each timestamp has a plot even if they feel more like individual scenes or moments rather than plots as some are more used to in films. Each time stamp deals with rejection, isolation, connection, and acceptance in different ways. So while there is no clear A-, B-, or C-Plot, each time stamp works as their own A-Plot to explore the themes in a variety of ways, particularly by starting out in a place of rejection and moving to acceptance or a place of connection to isolation.

Please note that there are many ways to write multiple plots, there are just two examples.

While there are flaws within season 1 of RNM, overall the themes stayed consistent throughout the season, mainly the theme of alienation. The theme threads through the Alien’s isolation/alienation from humanity which is particularly seen through Michael’s unwillingness to participate and Isobel’s over participation. There is Rosa’s isolation from others, how her friendship with “Isobel” ended up compounding her existing alienation from her support system due to her mental illness and coping mechanisms. We see how Max and Liz couldn’t make connections. This theme presented itself over and over in season 1. While this essay is not an exploration of the breakdown of themes in season 2, it should be noted that there were some threads that followed throughout the season. The theme of mothers/motherhood was woven throughout season 2, with some elements more effective than others. Please contact the author for additional thoughts on Helena Ortecho and revenge plots.

One of the largest problems within season 2 was the sheer number of plots jammed into the season. These plot threads often ended up hindering the effectiveness of the themes and made the coherence of the season suffer. Additionally, a lot of them were convoluted and difficult to follow.

Thesis:

Essentially, season 2 was a mess. To look at it holistically is almost an exercise in futility. Either you grow angry about the dropped plots and premises, you hand wave them off, or you fill them in for yourself. Instead, this essay proposes to look at individual elements to explain why Forrest should have stayed evil.

We first meet Forrest in 2.04 when he is introduced on the Long Family Farm, which we later learn was the location where our past alien protagonists had their final standoff. He’s introduced. He’s largely just there. The audience learns he has more of a history with Michael. In 2.06, we meet him again with his dog Buffy (note: poor Buffy has not been seen again and we miss a chunky queen). There’s mild flirting, Alex is invited to an open mic night, which he attends. For the purpose of this essay, the author’s thoughts on the poetry will not be expressed. Readers can take a guess.

It is after this point that the author speculates the Decision was made. This choice to make Forrest not evil- paired with the aforementioned ‘can’t kiss, someone’s sick’- impacted the plot. We have Alex have a scene with his father- which the author believes could have been pushed to a different episode- and then have Alex go on a date and then not kiss Forrest at the end of the night. Here, the audience sees Forrest hit Alex in the leg, allegedly not knowing he had lost his leg despite ‘looking him up’, which parallels the shot to the leg that happens to Charlie. Besides wasting this ABSOLUTELY TEXTBOOK SET UP WTF, it also takes Alex away from the main plot and then forces a new plot for him. Up to this point, Alex’s plot was discovering more about the crash and his family’s involvement. Turning Alex’s date from a setup for evil Forrest to a Coming Out story adds yet another plot thread to a packed season. It is also the author’s thought that this is where the convoluted kidnapping plot comes in. With Forrest already in 2.10 for a moment, a plot where Alex is evil has Forrest attack him for Deep Sky rather than Jesse abduct him for a piece of alien glass Alex was going to give him anyway and then for Flint to abduct Alex from Jesse. It’s messy. In a bad way. Evil Forrest would have been a cleaner set up: no taking back a piece of alien glass Alex gave to Michael in a touching moment. No double abduction. Instead, there is only Forrest, who Alex trusts, breaking that trust to take him as leverage over Michael.

Implications:

Now, Alex has two plots (Tripp & Coming Out). The Coming Out plot is largely ineffective, as they are only relevant to scenes with Forrest and have the undercurrent of there only being a certain acceptable way to be out. This could have been used for Alex to discover his comfort levels, mirroring Isobel’s self discovery, but there was not enough screen time for that. Additionally, Isobel’s coming out story was about her allowing herself the freedom to explore. Alex’s story was about the freedom to… act like this dude wanted him to. Alex’s internalized homophobia played out often in the series but it was also informed by the violence he experienced at Jesse’s hands and the literal hate crime he and his high school boyfriend experienced. With that in mind, the “kissing to piss off bigots” line comes off poorly. This is a character who experienced what a pissed off bigot could do- reluctance to kiss in public is not the same as not being out. There is more to be said on this topic, but as it is not actually the focus of the essay, it will be put on hold. To surmise: Alex’s coming out is attempted to be framed as being himself, but it is actually the conformity to someone else’s ideals. It does not work as an antithetical to Isobel’s story, as the framing indicates that the conformity/right was to be out contradicts Isobel’s theme.

Further Research:

MAKE FORREST EVIL YOU COWARDS

Author Acknowledgements:

The author of this paper acknowledges that the show took some strides to mend this problem. However, once again no consensus could be found on whether Forrest was a low-level member of Deep Sky and thus just allowed to fuck off on a bus, or his job was recruitement because he did a piss poor job of making Alex not join.

#anti forrest long#i guess#evil forrest propaganda#I asked and no one said don't post it so...#here it is#I started writing this roughly 7 months ago

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

I want to express an unpopular opinion. I hope for your understanding, because such things don't like to listen. Why does everyone think that Hawks is a bird? I couldn' fit my logical arguments into the askbox :( (about how he sits on a pole "like a bird", supposedly likes jewelry and so on). Even his quirk is called Fierce Wings, not a Hawk, not a Red Bird. Do you remember the names of the quirks of Hound Dog and Tsuyu-chan? We haven't evidence to believe that Hawks is behaves like a bird.

I do believe very much he’s a bird, and if you would let me friend, I would love to try and prove it to you because I think the evidence is overwhelming. I’ll make a TL;DR at the end but I’d really like to take the opportunity to perhaps teach others at least one method for literary analysis since it can be a really dry and boring subject to learn in school but is SO useful not only for getting good grades but getting into colleges as well as interpreting both entertainment and genuinely important information like the news, history, laws, and scientific papers. Using fiction - especially such a rich, engaging one like HeroAca - is a great way to try it out without the pressure of a grade. I don’t have the qualifications to teach in any formal capacity, but as a “peer” tutor I hope I can be helpful.

I’m going to put everything under the cut from here because this is going to get LONG, but I promise the TL;DR at the end will be very easy to read. If you liked this sort of unofficial tutorial please let me know. I’d love to help make “academic” skills like this more accessible for those who might benefit from it and enjoy it, but it doesn’t make sense to put in all that effort moving forward if I’m garbage at it.

Before we get too into things, I want to lay out a few notes to keep in mind as we go.

I will only be using the official translations from Viz’s Shonen Jump website when available. Fan translations are more than close enough to casually enjoy and follow the story, but professional translators are paid to know and get various nuances correct and some of the trickier cultural background behind certain phrases (for example, the phrase “where the rubber meets the road” might make zero sense in a foreign language if translated literally, so an equal cultural phrase should be used instead) that give more exact information. Rarely is this too important, but sometimes it helps, plus it supports the source material.

If you’ve followed my blog for a while you might know I’m very fond of doing this kind of thing in my spare time and that I’m a huge fan of YouTube channels like Game/Film Theory, Overly Sarcastic Productions, Extra Credits, and Wisecrack that do this kind of thing with popular media as well. If you like this sort of content, may I encourage you to check them out after this to see how else you can apply these kinds of analytical skills to things that aren’t homework.

My writing style tends to meander, but I do my best to cut out the fat and only include relevant information so even though there’s a lot of information here, please know that I’m trying to be thorough and explain things to the best of my ability. If I seem to go off on a tangent, I’m trying to set up or contextualize information to explain why it’s relevant and then come back to the point. In other words, please be patient and bear with me as I go.

Now, to start, I want to explain at least my method for analyzing a text/piece of media. There is a set order and number of steps to take, and it’s as follows:

Read the material all the way through.

Come up with a hypothesis about something you’ve noticed when reading it. (In this case, it’s “Is Hawks actually supposed to be a bird?”)

Collect as much relevant information as possible and test the evidence to see if it supports the hypothesis we’ve made.

Step back and look at everything again with those points in mind.

Determine if we were right or wrong with the evidence we have.

If we were wrong, go back to step 3 to figure out what fell apart and see if we need to go back to step 2.

If that sequence sounds familiar it’s because it’s the scientific method! Aha, didn’t think we’d be pulling science into all this, did you? Don’t worry, we won’t be putting numbers or formulas anywhere near this discussion - the scientific method is just a way we can observe something and test if what we thought about it is actually true; and it applies to almost everything we as humans can observe - from the laws of the universe, to arts and crafts, to philosophy and religion, and so on! When you think about it that way, whole new possibilities can open up for you when it comes to understanding how the world works.

So with that set let’s (finally) begin!

Steps 1 and 2 are already done. We’ve read the manga and want to prove that Hawks is a bird. (We’re going to try and prove he IS a bird because in the context of the series there’s a lot that *isn’t* a bird and less stuff that *is* which will make our job easier.) So now, we’re onto:

Step 3 - collect data and see what conclusions we can get just from our evidence.

Now, to pause again (I know, bear with me!) there’s a few different kinds of information and considerations we have to keep in mind as we collect. There are four kinds of information that are important to know about in order to determine if it’s good data that will help us with the testing phase in Step 4. The kinds of information to keep in mind are:

Explicit information - this is information that is directly spelled out for us. For example, Hawks says, “I like my coffee sweet.” and his character sheet says “Hawk’s favorite food is chicken.” That’s all there is to it, and it’s pretty hard to argue with. This is the easiest type of info to find.

Implicit information - this is info that isn’t directly spelled out but is noticeable either in the background or as actions, patterns, or behaviors that can be observed. For example, Hawks has mentioned in at least three very different places his concerns over people getting hurt while he tries to get in with the League:

Chapter 191 when confronting Dabi about the Nomu he says, “You said you’d release it in the factory on the coast, not in the middle of the damn city!”

Chapter 191 again in a flashback with the Hero Commission he asks, “What about the people who might be hurt while I’m infiltrating the League?”

Chapter 240 when discovering how much influence and power the League has gained, “If someone had taken down the League sooner, all those good citizens wouldn’t have had to die!”

Hawks never says in so many words, “I never want innocent people to get hurt under any circumstances!” but the pattern of behavior and concern is consistent enough to form a pattern and clue us in that this is a key part of his character to keep in mind.

Peripheral information - this is information that isn’t directly to do with Hawks or maybe even the series as a whole but is still relevant to keep in mind for his character and the questions we’re asking. This may include extra content that isn’t the “series” proper, but is still an official source like interviews with Horikoshi, etc. but it can go even further. For example, while we try to prove that he’s a bird, we should have some knowledge about what makes a bird a bird, some specific and notable birdlike habits/behaviors/features, etc. This is just to show how wide-ranging we need to cast our informational net.

Contextual information - this will be important when we get to Step 4, but it’s good to keep in mind now. This is when we compare evidence against the broader scope of the series and consider the circumstances under which we find the information. For example, if I told you, “Harry kicked a dog.” you might think “What a jerk! What decent person kicks a dog?”; but if I said, “Harry kicked a dog while trying to keep it from biting his kid.” suddenly it re-frames the story. “Is the kid ok? Why was that dog attacking? Harry put himself in danger to keep his kid safe - what a great dad!”

I’ll go chronologically to make it easier to follow my evidence as I gather and give references as to where I found that information. I’ll go through the manga first, and then any peripheral sources that are either direct informational companions to the series (like character books or bonus character information sheets) and interviews with Horikoshi. Please note the categories these details fall into may vary based on opinion/interpretation, but I did my best to list them out for reference.

Chapter 185 - Explicit Type: Feathered wings - regardless of the specifics of his quirk it’s undeniable his wings are made up of feathers which is a distinctly birdlike quality. There are many mythical creatures and even dinosaurs that also have feathered wings, but this is our first big piece of evidence.

Chapter 186 - Peripheral Type: Large appetite - birds have an incredibly fast metabolism because flying takes so much energy. They’re constantly eating. Plenty of young men are big eaters, but it was specifically pointed out and works towards our hypothesis so we’ll keep it in our back pocket for now.

Chapter 186 - Implicit/Peripheral Type: Fantastic vision - Hawks senses the Nomu coming before the audience even is able to make out what’s headed their way. It could be implied his wings caught it first, which might be the case, but he looks directly at the Nomu and brings Endeavor’s attention to it. Birds have fantastic long-range vision, especially birds of prey that mainly swoop in from high in the air to ambush highly perceptive prey. Also good to add to the pile.

Chapter 192 + Volume 20 Cover - Implicit/Peripheral type: Wears jewelry and bright colors - birds are well documented to be drawn to bright colors and are known for decorating their nests with trinkets. Scientists actually have to be careful when tagging birds with tracking bracelets because they can accidentally make him VASTLY more popular with the ladies by giving him a brightly colored band to the point they can’t resist him! Male birds are also known for having bright, colorful displays for attracting and wooing mates. While Hawks isn’t the only male character to wear jewelry in the series, he’s the only one (to my recollection) that wears as MUCH jewelry so often both during and outside of work. It may not be obvious, but the illustration on Volume 20 is actually an advertisement for his line of (presumably) luxury jewelry. In other words, Hawks on some level is synonymous with style and flair to the point he can make money by selling jewelry with his name on it.

Chapter 20 Volume Cover - Explicit Type: Hawk emblem on the watch face - If the name “Hawks” didn’t give it away, he’s very clearly trying to align himself with more avian qualities if his merch has bird motifs. In other words Hawk = “Hero Hawks” and “Hero Hawks” = bird.

Chapter 192, 244, clear file illustration - Peripheral Type: birdlike posture. Chapter 244 isn’t quite released yet on the official site as of writing this, but when Hawks swoops in and beats the kids to the punch apprehending the criminals trying to subdue Endeavor, his hands are clenched in a very talon-like manner similar to a swooping eagle. When walking with Endeavor in 192, he holds his resting hand in a similar fashion. On the clear file illustration he’s not only perched on his tippy toes in a pose that has been famously called “owling” (remember that trend/meme, y’all?) but his wings are slightly outstretched to catch the breeze to keep from falling over which a lot of birds can be seen doing when they don’t have great purchase on a surface in a place that’s a little windy. The fact that he seems to gravitate to high places like birds are often seen doing might also be a noteworthy indication.

Extra sources:

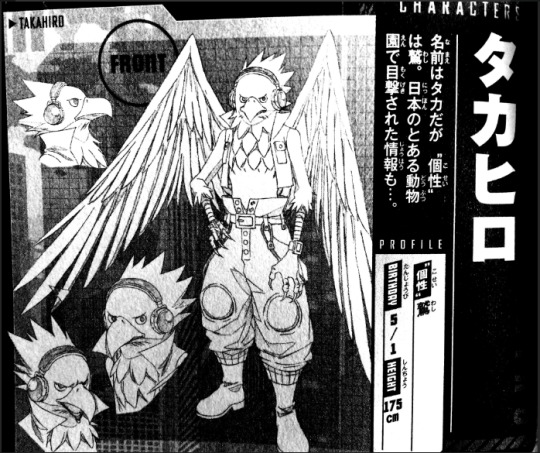

Hawks Shifuku: Horikoshi describes Hawks as a “bird person” and says that his initial design was based off of Takahiro from his old manga.

Takahiro’s design:

Current character design: The banner image on my blog was commissioned from a friend of mine who doesn’t follow the series. When I showed her reference images of Hawks, you know what she said? “Oh! His hair is feathers!” Even his eyebrows have that fluffy/scruffy texture to them that his hair has. The markings on his eyes can also be seen on him as a young child in Chapter 191 which means it isn’t makeup meant to tie in a theme or look. He has those dark, pointed eye markings like many birds do. So on some genetic level he resembles a bird.

Step 4: Testing our hypothesis with the gathered evidence.

There’s already a lot of compelling evidence that already closely aligns him to birds which is promising. However, to really prove our point we should try to prove beyond a shadow of a doubt he is a bird. To do that this time around I’m going to see how the series treats people with animal-based quirks and see if it’s consistent with the way Hawks is portrayed.

You bring up Hound Dog and Tsuyu, and they’re fantastic examples. Let’s start with Hound.

He’s pretty straight forward - he’s like a dog. He has a dog face, has dog-like tendencies, and dog-like abilities. Superpower: dog.

And in Tsuyu’s case - quirk: frog, just frog. She’s stated explicitly to have frog-like features, frog-like tendencies, have frog-like abilities, and even comes from a “froggy family.”

So with these two very explicitly animal-like characters the common theme seems to be “If they’re considered to be like a specific animal, they have to physically resemble that animal, act like that animal at times, and have abilities like that animal.” Let’s see if another animal-quirk character matches up and then put Hawks to the test.

Spinner’s quirk is Gecko. Based on our criteria, is he a gecko?

Does he look like a gecko, even vaguely?

Yes, he’s covered head to toe in scales, and his face is very lizard-like.

Does he occasionally act like a gecko?

Unclear. We haven’t really seen any evidence of this, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t. For the sake of our argument, we’ll just say no and move on.

Does he have gecko-like abilities?

Yes! Though most of his abilities are limited to things like being able to stick to walls, it’s still gecko-like in origin and qualifies.

Spinner hits clearly hits ⅔ criteria and our standards seem pretty consistent, so let’s see how Hawks stands up.

Does he look like a bird?

Not all of his features may explicitly scream “avian” at first, but upon closer observation and with his clear previous inspiration this is a resounding yes.

Does he act like a bird?

Many of the mannerisms and behaviors he displays can just be chalked up to him being a little eccentric, but with the sheer number of them that also parallel birds in some way this is also a pretty convincing yes.

Does he have bird-like abilities?

While most of the emphasis is on his wings and what they can do, it does seem that he not only possesses things like heightened senses which could be attributed to avian abilities but he also very much possess high intelligence and incredibly fast reaction times which birds are also known for.

Even if we only gave Hawks a “maybe/half a point” for those last two, he still meets the 2⁄3 that Spinner did. So we have another question to ask: Does a character have to have an explicitly named “animal” quirk to be considered to be/resemble a specific animal? Let’s look at Ojirou and Tokoyami for reference.

Ojirou’s quirk is just “tail,” but he’s been described by his peers and classmates as a monkey and does seem to share some more monkey-like features. It isn’t lumped in with his quirk because the only notable monkey-like quality he possesses is a tail. He doesn’t have fangs or an opposable toe - he just has a tail. For quirk classification as far as hero work goes, that’s the only important thing to note.

Tokoyami, on the other hand has an entire literal bird head, but nothing else. He has a beak, feathers, and even in illustrations of him as a baby he had fluffier feathers on his head. Even with only those details, he just screams “bird!” However, his quirk is classified as “Dark Shadow” because that’s what sets him apart for hero work.

Back at Hawks we see his quirk classified as “fierce wings” but like Ojirou and especially like Tokoyami, the emphasis on his wings is what sets his abilities as a hero apart. Otherwise, he’s just a guy who looks and acts a LOT like a bird.

But astute observers may have noticed I’ve left out a detail that’s more or less a nail in the coffin on the whole matter, so let me ask a question: Tsuyu in particular has something else of note that solidifies in our minds that she is, indeed, a frog - she explicitly calls herself a frog. Could we say the same about Hawks?

Chapter 199 - Explicit Type

Bingo. Hawks has known himself for as long as he’s been alive. He knows his habits, his impulses, his family/genes, and so on. If he calls himself a bird, are we going to call him a liar? In fact, he calls himself a bird not once, but twice!

That’s pretty much it. With the evidence stacked to that degree, I’d be hard pressed to NOT believe he’s a bird.

That was a long amount of text to get through, so if you’re here at the end thank you for sticking out with me to this point. I really appreciate it. This is more or less the process I use when analyzing anything and everything whether it be HeroAca related or not. Maybe it’ll help you if you’ve struggled with literary analysis, or at the very least I hope you got some enjoyment out of it.

TL;DR If Hawks looks like a bird, walks (acts) like a bird, is based on a bird (character), and calls himself a bird, he’s probably a bird.

#hawks bnha#bnha hawks#hawks#hawks mha#mha hawks#she writes#let's talk hawks#bnha meta#bnha spoilers#mha spoilers#manga spoilers

366 notes

·

View notes

Link

The tale of Halloween in Haddonfield, Illinois, has been told and retold: the night in 1963 that an angelic 6-year-old Michael Myers, dressed in a clown suit, brutally murdered his teenage sister, followed by the night 15 years later, again on Halloween, when he broke out of a mental institution in his famously mutilated William Shatner mask to terrorize the virginal babysitter Laurie Strode, a.k.a. Jamie Lee Curtis in the role that would make her the ultimate scream queen.

As Laurie, Curtis has battled the unkillable, silent but single-minded Michael Myers across five of the 11 films in John Carpenter’s Halloween franchise — including the newest entry, a sort-of sequel, sort-of remake directed by David Gordon Green that’s out this weekend.

Of all iconic horror franchises, none is quite as quirky and erratic as this one. Though the original film, Halloween (1978), is Carpenter’s signature film, it’s the only one in the series he directed. He then co-wrote and co-produced a sequel with his collaborator Debra Hill, but their subsequent attempt to keep the series from becoming formulaic would end up sending it meandering off in random, truncated directions.

As a result, where most horror franchises stick to their main story concept and expand it over time, the Halloween franchise keeps getting lost and restarting itself — hence the shaky continuity of the latest film. The only thing we can say for sure about the timeline is that the first two films are paired and occur in sequential order on the very same night. After that, the franchise goes haywire, spinning through one-offs, sequels, and remakes that perpetually overwrite each other.

Of course, this cyclical quality may also be why Halloween is so enduringly popular — you definitely don’t need to have seen every film in the franchise to understand what’s happening, or to enjoy the next one.

Of course, there’s another facet of the series’ enduring popularity that can’t be overlooked, and that’s the cat-and-mouse game between Laurie and horror’s most implacable killer. So if you’re a fan of Michael Myers, you came to the right place: Let us walk you through the movies and tell you which are indispensable for the casual Halloween fan and which are skippable (most of them).

Before we get started: With a franchise this inconsistent, it’s good to establish which parts of the films are consistent. That way, when you brush up on your Halloween movies, it won’t matter if you skip a few. Here are the main rules of the franchise — all of which, unsurprisingly, involve its iconic villain.

1) Michael Myers always wears his mask — and he never, ever speaks.

You rarely see him without his mask in any of the films. The Shatner masks have become the stuff of horror film legend. As for his voice, you only hear him speak in one film in which his childhood is explored — before he became a monster. Beyond that? Nada.

2) Michael is usually credited as “The Shape” and is always referred to at some point as the Boogeyman.

A crediting tradition begun in the first two films and intermittently revived over the years, “The Shape” is back for the 2018 sequel. The Boogeyman has remained a constant.

3) Michael is always obsessed with Laurie Strode or her nearest relations.

The reason for this is revealed in the second film, and all the following films have retained this explanation for their connection.

4) Michael never runs. He always walks slowly after his victims, and he’s never in a hurry.

Part of the terrifying thing about Michael is that he’s surely the most casual serial killer in history. He never picks up the pace beyond a leisurely stroll, and he often seems to be nearly lackadaisical in his attempts to off his prey. Of course, he nearly always gets them in the end.

5) Michael can’t be killed.

This one is obvious, but it bears stating for the record. Throughout the franchise, he will survive multiple gunshots, stabbings, explosions, car crashes, electrocution, being run over, having his skull bashed in, being set on fire multiple times, and (sorta) being decapitated.

Got all that? Great. Let’s go trick-or-treating!

The Shape having some fun.

Tagline: “The night HE came home!”

Is it a trick or a treat? Definitely a treat.

Halloween is famous for lots of reasons. It singlehandedly launched the era of the slasher film. It’s John Carpenter’s debut film, a low-budget indie that made an astronomical profit and launched his career. It’s got one of the most famous film scores and horror themes in history, written by Carpenter himself. It remains an incredibly creepy film, full of lingering and now-iconic shots of its killer stalking through idyllic suburbia, biding his time or casually observing his kills. And, most crucially, it introduced us to one of horror’s most famous villains, destined to be eternally mentioned in the same breath as Freddy and Jason.

Halloween is often credited as being the first example of the slasher subgenre of horror, and for introducing the world to the concept of the Final Girl: the one girl, usually singled out for her virginal qualities, who gets to survive the cinematic massacre of all her counterparts.

Except neither of those things is true. The slash-happy Giallo genre of Italian noir thrillers predates Halloween by about a decade, and two earlier slasher movies gave us the prototypical Final Girls: Tobe Hooper’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre and the Canadian cult classic Black Christmas, which were released a few months apart from each other in 1974.

However, Carpenter’s tale did serve to mainstream both the slasher film and the Final Girl, thanks largely to the magnetism of Jamie Lee Curtis as the canny, if mostly helpless, Laurie Strode.

Laurie typified the Final Girl trope from the start: She was “too smart” for boys and dressed like a dowdy homemaker, in contrast to the other girls with their trendy fashion and sexual exploration; in other words, she embodied the kind of chaste virtue that ensured her survival. But Curtis managed to pull off this role with a kind of fierce, gleaming shrewdness beneath the passive exterior — and two decades later, in her return to the franchise after a long hiatus, she would really throw off the helpless act once and for all.

The other main character of Halloween is an unlikely one, but nonetheless a fan favorite: Michael’s zealous therapist Dr. Loomis, played by the ever-zany Donald Pleasence, who would remain the heart of the franchise until his death.

Then there’s the specter of Michael himself, who’s played mainly by the actor (and later established director) Nick Castle. As horror villains go, Michael is ranked very high on the “too unbelievable to be effective” meter, but there’s something truly and indelibly terrifying about him, from the moment he shows up for his first killing spree as a kid, dressed in a Harlequin costume, to the time he returns to skulk silently around Laurie’s suburban neighborhood, dangling a knife and wearing a mask that’s dirty, mottled, and still creepy as hell.

It’s a little-known fact that the Halloween franchise is actually sponsored by jack-o’-lanterns. Universal/IMDB

Tagline: “More of the night HE came home.” (I guess modern horror was still working out how to really market this franchise thing, huh.)

Is it a direct sequel? Yes.

Is it a trick or a treat? For true Halloween fans, it’s a treat, albeit a plodding one.

Halloween 2, also written by Carpenter and Hill, picks up immediately after the first film, still on the same Halloween night. With Loomis leading police all over town looking for Michael, our killer naturally hightails it to the hospital where Laurie is recuperating from her injuries and proceeds to kill everyone on staff in order to get to her. The movie concludes with the shocking revelation that Laurie is Michael’s other sister, born too young to know him and sheltered from the truth all her life — until, of course, her past literally catches up with her on Halloween.

What makes this film notable among the franchise is that it establishes the central conflict of Michael versus the town of Haddonfield itself. Haddonfield is the only “character” that consistently appears throughout the Halloween series (minus the outlier that is the third film), and its relationship to Michael changes in interesting ways over the decades.

As films go, however, Halloween 2 isn’t very good. Laurie is relegated to an even more useless role than in the first film, spending the movie disabled due to her injuries. And even though we’re only on the second film, the murders already feel formulaic and perfunctory; gone are the creatively displayed bodies and carefully arranged murder tableaus, staged to increase the horror for everyone who finds them.

Perhaps because it’s the same night and he’s been on his feet all day running from the law, and, oh, yeah, at some point he apparently absorbed six bullets to the chest and head, in Halloween II Michael’s pretty “whatever” about how the bodies fall. He does get to fake out a really dumb cop by pretending to be dead, though, and he clearly enjoys that bit, so you do you, Mikey.

I’m angry that this still shot makes this film look so much cooler than it is. Universal/IMDB

Tagline: “The night no one comes home.”

Is it a direct sequel? No, it has nothing to do with any other Halloween movie.

Is it a trick or a treat? This movie is a dirty trick on all Halloween fans, but worth checking out just for the weirdness — especially for John Carpenter completists.

After Halloween 2, Carpenter and Hill had a combined vision for the future of Halloween: turn it into a series of anthology films rather than continuing the story of Michael Myers. As such, Season of the Witch, directed and written by Halloween’s production designer Tommy Lee Wallace, has nothing to do with the prior two films apart from recalling a single vague line in the second film about how Samhain, October 31, was a Druidic holiday often accompanied by ritual sacrifice.

Today, we’re used to horror franchises that expand out from their original storylines and go in different directions, thanks to more recent series like Paranormal Activity and The Conjuring. But Season of the Witch lacked any connective tissue with its predecessors and strayed too far from the formula fans had come to expect. In fact, Season of the Witch actually made the original Halloween a movie that exists within its storyline, which totally destroyed any semblance of continuity.

Season of the Witch instead treads a line between Lovecraftian horror and a corporate sci-fi dystopia, planting itself in California instead of Illinois and insinuating a terrifying global Halloween night conspiracy, all originating in a tiny rural company town. Frequent Carpenter collaborator Tom Atkins stars as a middle-aged doctor drawn into the madness after a patient dies at the hands of mysterious suit-wearing shills for a corporation that sells Halloween masks. Yes, that is a real sentence I just wrote.

The film meanders between Atkins’s frequently far-fetched sleuthing and sinister happenings around the factory and its town, while the company owner, a cross between an evil Willy Wonka and Lord Summerisle, oversees all. The whole ridiculous plot comes to a head with about as much incoherence as you’d expect based on everything I’ve just written.

Predictably, Season of the Witch was a box office flop and ended Carpenter and Hill’s hopes of turning the franchise into an anthology series. But then it gradually became a cult classic among horror fans; you can see its influence on modern horror films like Cabin in the Woods, and its fans argue that if it had been a standalone film called Season of the Witch, its reception would have been much different.

Also, the soundtrack to Season of the Witch, again scored by Carpenter, contains a theme titled “Chariots of Pumpkins,” and it is fantastic.

Donald Pleasence reacts to the news that he has to keep making these films. Universal/IMDB

Taglines: “Tonight, HE’S BACK!”; “Michael lives. AND THIS TIME THEY’RE READY!”; “Terror never rests in peace.”

Are they direct sequels? Yes, very loosely.

Are they tricks or treats? TRICKS, don’t be fooled — we watched these films so you won’t have to.

I need to state for the record that Donald Pleasence is a truly great actor. His performance in the Outback horror Wake in Fright is unforgettable. He was a perfect Bond villain. He was nominated for four Tony Awards! But he also loved to chew the scenery, and the middle period of the Halloween franchise gave him plenty to sink his teeth into.

The fourth and fifth films, churned out in 1988 and ’89, attempt to carry on the saga of the Strodes and Michael Myers without Jamie Lee Curtis. A slew of new writers and directors dropped into the franchise, and the fourth film replaced Laurie Strode after killing her off in a car accident, sight unseen, by inventing her 8-year-old daughter, an annoyingly cherubic little girl named Jamie.

Nothing that happens in Halloween 4, 5, or 6 ultimately matters because they’re all generic teen slashers with Spielbergian little kids and a raving Pleasence at their centers, and because the sixth film promptly kills Jamie to make way for a new set of victims (including Clueless-era Paul Rudd) and a whole lot of wacky new plot: Michael apparently fathered a son by his niece Jamie (wtf) while she was being held hostage for, like, a decade (wtf!) in a full-on goth cult(!!!) as part of yet another vast Druidic conspiracy orchestrated by the head of Michael’s sanitarium to mystically implant Michael with superhuman sociopathy, because HALLOWEEN.

But none of that matters either, because Halloween 6 was widely hated, it flopped at the box office, and then its dumb plot was also totally ignored by every other film to follow.

However, one thing that is interesting in these films is the development of Haddonfield as a self-aware character in the tale of Michael Myers. The police force evolves into an overeager, hapless army pitting itself against Michael’s eventual return, while the townspeople, believing he’s finally gone, turn him into a proper urban legend.

The main draw of this misbegotten middle part of the Halloween saga is Pleasance’s Dr. Loomis. Armed only with a pathetic and paltry pistol, Loomis seems to be the only character capable of facing down Michael again and again and surviving to tell the tale. And Pleasence always manages to walk a line between stone-cold sanity and madness that keeps Loomis vulnerable and endearing even at his campiest.

Unfortunately, Pleasence died after filming but before the release of the sixth film, which is dedicated to his memory. And without him, there really was only one other person who could keep the Halloween flame burning.

We stan a scream queen with a kickass haircut and a survivor’s outlook on life.

Taglines: “The night SHE fought back!”; “This summer, terror won’t be taking a vacation.” (This one makes sense when you realize the film was released in August.)

Is it a direct sequel? Yes, as the title implies.

Is it a trick or a treat? Honestly, this one’s a treat.

Director Steve Miner wisely brought Jamie Lee Curtis back to the franchise for H20 by completely ignoring anything that happened in films 3 through 6 aside from the barely mentioned car accident used to kill off Laurie Strode to begin with. Here we learn she faked her own death, moved out to California, and became a prep school head under an assumed identity. Michael tracks her down anyway, just in time for her son’s 17th birthday, and the madness begins again.

Two things are apparent when you watch H20. The first is how much the ’90s did to advance the treatment of women in horror films, and how markedly different adult Laurie is from her tepid, terrified younger self. Though she’s still clearly traumatized from what happened to her, she’s also built an amazing life for herself as an academic and a mother — and now she’s prepared to do battle to keep that life. H20 is the first film where any of the women targeted by Michael, or indeed any of the victims at all, really attempt to fight back instead of just running around in terror for most of the movie. And the film goes a step further by having Laurie choose to stay and confront Michael even when given the opportunity to escape.

The second is how much of an immediate impact Scream had on horror films of the late ’90s. (At one point, the film shows its group of teenagers watching Scream 2 on Halloween night.) H20 is far more character-driven than any of its predecessors, and it pivots around Laurie and her relationship with her son (Josh Hartnett). This is the moment you can see the Halloween producers finally figuring out that horror franchises can be about more than just horror.

Please, let the white dude cosplaying as Samuel L. Jackson tell you everything you need to know about this movie.

Tagline: “Evil finds its way home.”

Is it a direct sequel? Supposedly it’s a loose sequel to H20, but we reject this premise.

Is it a trick or a treat? The WORST TRICK, stay away unless you like kitschy early internet nostalgia and lots of blurry found-footage trickery.

Halloween: Resurrection is so on-trend for summer 2001 that it’s almost worth watching for the cheesy time capsule aspects: the impact of early reality television, the advent of online relationships, and, of course, the way both Scream and Blair Witch Project had led to a trend of so-meta-it-hurts horror films experimenting with found footage and shaky cams. This one sees a bunch of college students watching and cheering on a bunch of other college students — and Busta Rhymes, for some reason — as they invade the old Myers house for a live televised reality show that of course turns into a house of horrors when Michael shows up for some slice-and-dice.

Where is Laurie during all this, you ask? Gone is the assertive survivor Laurie from H20. The film strips her of her new life and plants her in an institution as a result of the ending of that previous film. Then it kills her off within the first 10 minutes, giving the series its low point when she kisses Michael on the mouth and promises to “see you in hell.”

What Resurrection misses completely is that Halloween just isn’t Halloween without Michael battling a specific set of characters. To the extent that Halloween 4-6 worked, they worked because Michael was still pursuing the Strode family and still combating Dr. Loomis. Take away that connection and you’re left with a formulaic slasher movie that no amount of clever stylization can cover.

Taglines: “Evil has a destiny”; “Family is forever.”

Are they direct sequels? No, these are spiritually faithful remakes of both.

Are they tricks or treats? Very sharp treats.

From the emotionally violent opening scene, in which we gradually realize we’re seeing a picture of Michael Myers’s deeply dysfunctional home life before he snapped and went on his childhood killing spree, Rob Zombie’s take on Halloween announces itself as something different, a cut above all the other films in the franchise, bar the first one.

By giving Michael a backstory similar to the ones that often breed real-life serial killers, the film humanizes him and belies the idyllic “terror comes to suburbia” aspect of all the previous films. The film also delves into an aspect of his story that to this point had only been described after the fact: his psychotherapy sessions with Dr. Loomis, here played by Malcolm McDowell. The second film, Halloween II, also extends this interest in psychology to Laurie Strode (played this time by Scout Taylor-Compton), plumbing the emotional and psychological connection between her and Michael.

Like all Rob Zombie films, these are steeped in violence and obscenity, but the deranged atmosphere does more to make Michael feel interesting than all the previous films — he’s both a superhuman killer and a boy plainly driven by the sociological factors that turn people into sociopaths. As horror films go, these are among the better offerings of the aughts’ crop of gritty slashers, à la Wolf Creek. And because it’s still about Michael Myers, it all feels epic and larger than life in a way few of those other films do.

[embedded content]

Of course, we can’t tell you too much about the new film, except to say that it will feel very familiar to Halloween fans. Curtis’s Laurie is back in full-on survivor (and survivalist) mode. And this time, her whole family has to face down Michael with her — whether they’re ready or not.

This version of Halloween pays direct homage to the original Halloween in numerous ways. It expects its viewers to know and love the original film, and to react to its echoes years later. Above all, this Halloween is fully aware of what Halloween films do best: let Michael Myers terrify viewers as he conducts his regularly scheduled eerie rampage through Haddonfield. So prepare to meet the face of pure evil — for the 10th time in four decades.

Original Source -> Halloween: a complete guide to horror’s quirkiest, most erratic franchise

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes