#studies in matrilineal descent

Note

what are your personal thoughts on claiming Jewish identity? I know you do not speak for all Jewish people but I am curious on your personal take. I just discovered I am matrilineally Jewish but I was raised in a (casually) christian upbringing. I am interested in studying Judaism more deeply as well. but would it be improper to say that I am Jewish?

Who constitutes as a Jew is incredibly complicated, and a rabbi would be much better equipped at answering your question than I am. If your mother's Jewish identity is in question, you should bring your knowledge and evidence to a rabbi, preferably one that is in a movement you could see yourself being involved in. I recently learned that the reform movement denies matrilineal descent in certain cases (if your great grandmother on your mother's side was Jewish but either she or her daughter converted "out" of Judaism, leading to your mother not being raised Jewish). So, the question of whether you're Jewish or not is up in the air and more information is needed.

All that being said, if you still identify as Christian, this could cause a lot of tension should you start claiming a Jewish identity within Jewish spaces. That has nothing to do with whether you are halachically Jewish, but just a warning.

As for my own personal opinions about who constitutes as a Jew, it isn't my place to say them (unless it is regarding messianics). Only HaShem has the true answers for who is a Jew and who isn't, and I trust He will decide.

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indeed, if one looks at the writings of those women who were articulating cultural feminism in this period, it is clear that they were motivated in part by a desire to put an end to the painful and often immobilizing discussions about women's differences. Their hostility toward the left derived in large measure from its obvious commitment to analyzing class and race differences. Thus we find Robin Morgan and Kathleen Barry, two women who played a very important role in the articulation of cultural feminism, assailing feminists who wanted to explore questions of class, race, and sexual preference. For instance, at the schismatic 1973 West Coast Women's Studies Conference in Sacramento, California, Robin Morgan pleaded with the audience to recognize that "the point is that we as feminists must search . . . for the connectives between women. It is The Man who looks for the differences, " Barry, who helped organize the conference, denounced the women who raised the issues of class, race, and imperialism as saboteurs who "must be treated as the enemy from within" the movement. Barry was especially upset with Rita Mae Brown, whom the organizers had very reluctantly asked to lead a workshop on class:

“What does it mean when Rita Mae Brown, in a class workshop at this Women's Studies Conference, asks women to separate themselves into groups based on their class? It is perhaps the most hideous form of mimicry of the male class system of thought and politics. It is presuming that women are somehow responsible for the class men have provided for them. And above all, it negates the reason for us being together—to identify female first, with ourselves, with each other.”

Barry counseled feminists to bury their differences and concentrate instead on building a female culture. In a rehash of Alpert's recently published "Mother Right," Barry contended

“We must look to our matriarchal past for guidance in defining a culture that is a logical extension of nature. With the essence of motherhood and a sense of the preservation of life imprinted in our genes, matrilineal descent will naturally become the organization of the society we envision.”

Morgan had assumed the same stance earlier that year at the West Coast Lesbian Feminist Conference in Los Angeles in April 1973. Here, Morgan railed against leftist women, especially members of the Socialist Workers Party. According to one of the conference organizers, Morgan even tried to prevent the socialist-feminist workshop from meeting. Devoting much of her key-note talk to the gay-straight split, Morgan argued that the split had been "created by our collective false consciousness" and had been exacerbated and exploited by “The Man.” For some time, Morgan had been trying to mitigate tensions between heterosexual and lesbian feminists by emphasizing their commonalities. For instance, in a spring 1972 speech to D.C. feminists, she declared that "a lesbian is any woman who has ever loved another woman. By that definition every women in this room is a lesbian." At the Los Angeles conference, Morgan, repeating what Atkinson had argued in 1971, maintained that the real test of feminist commitment was not whether one slept with women, but whether one would be at the barricades. Morgan also argued that the real enemy facing the feminist movement was neither heterosexual women nor lesbians, but rather "the epidemic of male style among women." She contended that those lesbian feminists who advocated nonmonogamy, accepted transvestites and trans sexuals as allies, and listened to the rock group The Rolling Stones had adopted a “male style [which] could be a destroyer from within” the women's movement. Of course, the conjoining of masculinity and lesbianism was still sufficiently prevalent at least outside the movement that this accusation seemed almost calculated to stir up feelings of guilt. By defining the pursuit of relationships as female and the pursuit of sex as male, Morgan then tried to intimidate her lesbian audience back into the familiar terrain of romantic love:

“Every woman here knows in her gut the vast differences between her sexuality and that of any patriarchally trained male's—gay or straight. That has, in fact, always been a source of pride to the lesbian community, even in its greatest suffering. That the emphasis on genital sexuality, objectification, promiscuity, emotional noninvolvement, and coarse invulnerability was the male style, and that we, as women, placed greater trust in love, sensuality, humor, tenderness, commitment.” [her emphasis]

Morgan was trying not only to forestall the spread of "maleness" throughout the lesbian community, but also to persuade lesbians that they shared a consciousness and political agenda with heterosexual feminists. Morgan concluded her speech by calling upon women to create a "gynocratic" society:

“If we can open ourselves to ourselves and each other, as women, only then can we begin to fight for and create, in fact reclaim, not "Lesbian Nation" or "Amazon Nation"—let alone some false state of equality—but a real Feminist Revolution, a proud gynocratic world that runs on the power of women.” [her emphasis]

Although Morgan's critique of egalitarianism was quite cryptic, it was a significant statement. Tentatively, but increasingly, Morgan was suggesting that the left was dangerous not only because it was sexist and posited the primacy of class, but because it promoted egalitarianism. By the summer of 1972, Alpert maintains that Morgan was "beginning to reject not just the sexism of leftist men, but the very social democratic principles from which the [left] movement had developed."

-Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America: 1967-75

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

should i be finishing up studies in matrilineal descent? yes. am i doing that? no. no i am not. i am in full brad bakshi trauma brainrot. i will be writing about that an nothing else for the foreseeable future ✨thank you✨

#studies in matrilineal descent#my writing#my fics#mythic quest#brad bakshi#community#abed nadir#trobed#troy barnes

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

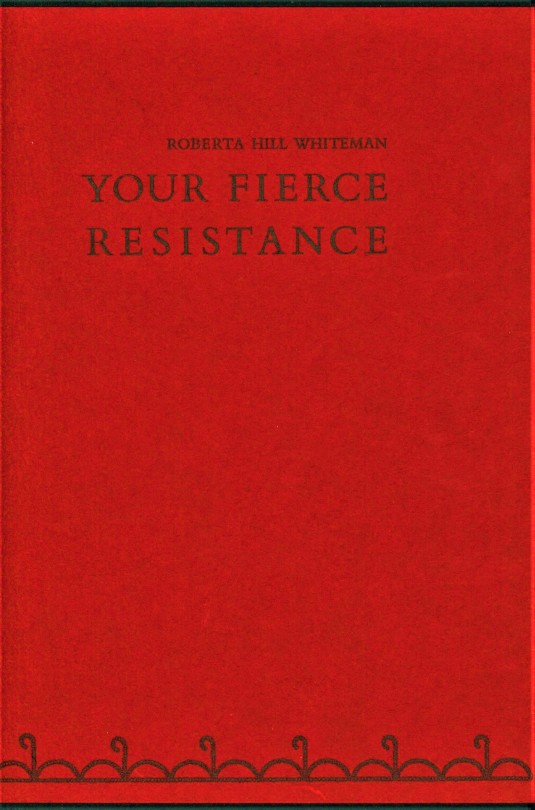

First Nations Fine Press Friday

Roberta Hill

In association with our post this week on Roberta Hill, we present the fine press printing of an excerpt from Hill’s 1993 poem, Your Fierce Resistance. Printed in an edition of 150 copies at the Minnesota Center For Book Arts (MCBA) in conjunction with literary center The Loft for the Inroads: Writers of Color series,Your Fierce Resistance is an excerpt of a longer poem of the same title. The full-length poem can be found in Roberta J. Hill’s (then, Roberta Hill Whiteman) second poetry book collection, Philadelphia Flowers: Poems, published by the Holy Cow! Press in 1996. The edition was was printed by Robert Johnson of the Melia Press and wood engraver, printer, designer, poet, and illustrator Gaylord Schanilec using Bembo type on Mohawk Superfine paper, with Fabriano Italia endsheets and Moriki Over Arches covers, supported in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

Hill completed her PhD with a biographical study of her paternal grandmother, Dr. Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill—the second American Indian woman to earn an M.D. in the United States. Minoka was of Mohawk descent, but had moved with her husband to the Wisconsin Oneida Reservation where she opened a “kitchen clinic” to serve the Oneida peoples. She’s said to have been adopted by the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin—the only person in the 20th century to be officially adopted by them—and was given the name Yo-da-gent, meaning “she who saves” or “she who carries help”.

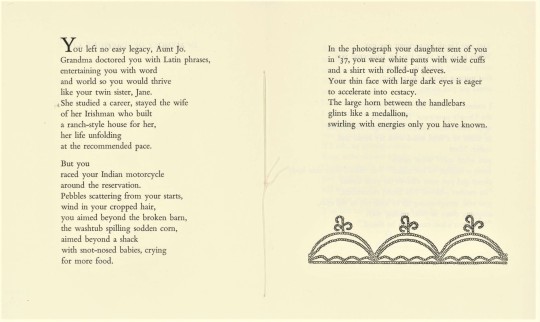

The book, however is dedicated to another family member, Josephine Coté, Hull’s matrilineal aunt. Nonconformity must run in the women of this family, as Hill’s writing honors her aunt’s outward resistance to all pressures of assimilatory expectations, both inside and outside the Oneida reservation. Hill recalls a conversation with Coté, in Your Fierce Resistance,

Then

you asked me, “What passes

from a mother to her child?” You shifted your thin body

closer and put your elbows on your knees.

“Its mother’s blood. The blood remembers,”

you said, straightening up to look me in the eyes,

snapping them in your teasing way.

“Whatever’s lost can often be found.”

Roberta Hill’s three poetry collections revolve around the communal feeling of disconnection within the Oneida Nation’s people, where she utilizes nature-centric Native American/First Nations ideals to take a firm stance against the capitalistic consumption polluting our environment. Hill has read her poems throughout the United States and at International Poetry Festivals in Medellin, Columbia and Poesia Do Mundo in Coimbra, Portugal, as well as in China, Australia, and New Zealand. Hill has retired from her position as a Professor of English and American Indian Studies, affiliated with the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, in May of 2020, and now lives in the Driftless area of Wisconsin.

View more Fine Press Friday posts.

–Isabelle, Special Collections Undergraduate Writing Intern

We acknowledge that in Milwaukee we live and work on traditional Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk, and Menominee homelands along the southwest shores of Michigami, part of North America’s largest system of freshwater lakes, where the Milwaukee, Menominee, and Kinnickinnic rivers meet and the people of Wisconsin’s sovereign Anishinaabe, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Oneida, and Mohican nations remain present.

#Fine Press Friday#Fine Press Fridays#Fine Press#Your Fierce Resistance#Roberta Hill#Josephine Cote#Lillie Rosa Minoka-Hill#Robert Johnson#Gaylord Schanilec#Minnesota Center for Book Arts#The Loft#Inroads#Writers of Color series#Mohawk#Philadelphia Flowers#Oneida Nation of Wisconsin#Native American Poets#Indigenous Writers#Bembo#Fabriano#Moriki Over Arches#National Endowment for the Arts#Limited Edition#Isabelle

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

I recently discovered my paternal grandmother’s family were sephardi jews who fled from Portugal to Brazil and then were forced to convert to Christianity. This caused be to start reading about Judaism out of curiosity about my heritage, however I’m unsure how to try to reconnect with the culture my family was coerced to leave behind and at the same time not appropriating something that is not mine. I’m aware that, at least to most jewish communities, I’m still goy since I do not have matrilineal descent. So, I should be careful to not invade and appropriate jewish culture. But I still feel sad about my line having “lost” it’s roots. Do you have any counsel about how to proceed?

A lot of Jews today don't care which side of the family was Jewish so long as you were raised Jewishly, but it sounds like you still have a few degrees of separation from that. I would definitely reach out to your local Rabbi! At the very least they can recommend fantastic resources for your study and let you know about all the local community events the temple/shul hosts throughout the year, that way you can keep touch with the local community :) We typically LOVE having guests. (My Jew Crew has a few honorary members who aren't Jewish, but support us and celebrate with us all the time because we're just pals. One of them is even our go-to hamentashen maker for Purim.)

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

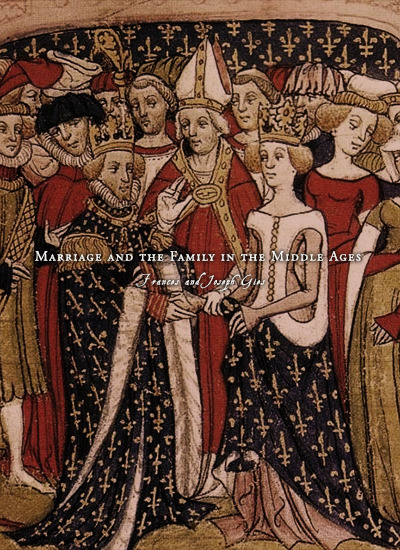

Favorite History Books || Marriage and the Family in the Middle Ages by Frances and Joseph Gies ★★★★☆

A general approach to the subject of marriage and the family in the Middle Ages poses fundamental questions that may be summarized under ten somewhat arbitrary headings. These will supply the basic lines of inquiry for the present book.

First, concept: What was the contemporary perception of the family? How was it viewed and defined? Outside forces such as economic pressures and mortality rates might govern the actual size and shape of the family, but the “ideal” type, expressed in custom and inheritance law, exerted crucial influence on attitudes and relationships, as well as on actions: who married and at what age, who stayed home, who held a position of authority in the family.

Second, function: Sociologists define the function of the modern family as twofold: the “socialization” of the child, and the channeling of the adult’s sexual and emotional needs. In the past, however, the family had other very important roles. It functioned as a defense organization, a political unit, a school, a judicial system, a church, and a factory. Over the centuries these functions have been surrendered one by one to the great external institutions of modern society, the State, the Church, and industry.

Third, kind of kinship system :to which the family belongs. In Western society today the larger kinship groups—the ancestral lineage and the network of living relatives—are of limited importance. In the Middle Ages, as in most societies of the past, they loomed large. The kinship vocabulary adapted by historians from anthropology is not yet entirely fixed or entirely satisfactory, but a large descent group that claims a common ancestor is generally called a clan; a smaller descent group in which ancestry can actually be traced, a lineage. The network of an individual’s relatives is called a kindred. A clan exists independently of its members and can own land and exert political power. A kindred, in contrast, has no existence as a separate body. It exists and acts only in relation to the individual. Kindred and clan (or lineage) can, and in the Middle Ages often did, co-exist. Clans or lineages are patrilineal if descent is traced through the male line, matrilineal if through the female. The network of kindred is said to be “ego-centered,” since its composition differs for all individuals except siblings. The kindreds existing in a given community form a series of overlapping circles. Kindreds may for certain purposes be defined as bilateral or cognatic if they include relatives on both father’s and mother’s sides, or as patrilateral (father’s side) or matrilateral (mother’s side). In pre-industrial society, the two kinds of kinship groups played important, often determinative roles in the transmission of property, the choice of marriage partners, the protection of the individual and the family, legal disputes, and many other aspects of daily life.

Fourth, size and structure: This is a subject to which historians have devoted a great deal of attention, making attempts to classify principal types. At one time it was assumed that the family had undergone a “progressive nuclearization” from the early Middle Ages to the present, a straight-line evolution from the clan to the extended family to the nuclear family. Recent studies have shown quite a different picture. ...

Fifth, economic basis of the family: In the pre-industrial world, the family was the principal production unit, in agriculture, manufacture, and commerce. At the pinnacle of ancient, medieval, and early modern society, the wealthy aristocratic landholding family functioned as a managerial unit, and its control and exploitation of property were related to its household structure and inheritance customs. The peasant family assigned its labors according to age and sex and, like the nobles, controlled and passed on its property in established ways. In the towns, families performed the various tasks of the clothmaking trade—spinning, weaving, finishing—, made leather, wood, and metal goods, and manufactured a variety of handicraft products, with husband and wife usually acting as partners.

Sixth, marriage: The process that forms the family has changed in ways that are visible and reasonably well understood. In the developed countries today only two parties are closely concerned in the marriage process: the bride and groom. Parental consent, though desirable, is not required. The Church may or may not play a part. The state licenses the marriage and imposes conditions of property ownership and inheritance. Private arrangements for the disposal of property, such as marriage contracts, are the exception even among the wealthy.

Seventh, relationships within the family:authority, age roles, sentiment or attachment, and sexuality. The egalitarian family, in which husband and wife share authority and in which democracy extends in some degree to the children, is a modern invention. In the past fathers had unquestioned authority, sometimes even the power of life and death. Wealthy families tended to be more authoritarian, poor ones, in which the economic contributions of the wife were indispensable, less so. Age differentials between husband and wife were also significant, husbands who were several years older than their wives tending to enjoy more authority. ...

Eighth, control of family size: In modern times, this has come to be a widely accepted imperative. In the past, limited economic resources often made it necessary for the mass of people, while inheritance problems sometimes suggested it for the wealthy. Late marriage was a means of shortening reproductive years. Abortion has been widely practiced in past centuries, and infanticide was legal in some societies and practiced in most. Contraception has been practiced or attempted by a variety of means. Finally, continence has been adopted or imposed.

Ninth, attitudes toward aging and death: At the other end of the life cycle, the family’s response in this regard has varied over the centuries. In some cultures, youth has reigned supreme, in others age has been accorded authority and dignity. The disabilities of age have been dealt with in different ways. Outlooks on death have changed radically, from the “tamed death” of traditional society described by Philippe Aries in his little book Western Attitudes Toward Death—death openly anticipated and prepared for—to the “forbidden death” of modern times, unmentioned and unmentionable.

Tenth, physical environment: Here the family has passed through historic changes: domestic architecture has affected the amount of privacy and comfort, the family’s space in its community, and relations with other families. Houses gradually differentiated among living, sleeping, and eating rooms. Dwellings came to provide separate accommodations for parents, children, servants, and animals. Houses of rich and poor, in city as in countryside, sought to integrate work space into living space. How family members interacted was affected by developments in furnishing, heating, and illumination: the bed, the dining table, and other furniture, the fireplace (a notable medieval invention), windows, candles, and oil lamps.

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

any poems on a daughter being rejected by their own mother who only loves the palatable parts of them which they pick and choose. (i'm thinking specifically of homophobia and mary jean chen's poetry but any other scenarios you want to include are very welcome). thank you so much and take care <3

hi! here are some poems for you. i’m swarmed by requests at the moment & my classes are starting, so i didn’t have the most amount of time to put together this compilation, but i’d HIGHLY recommend the book One Secret Thing by Sharon Olds, which revolves almost entirely around the poet’s complex, often toxic, relationship with her mother. i have also made another compilation about strained relationships with one’s mother here.

Chen Chen, “Race to the Tree” | my mother slapped me / after I told her I might be gay. / I didn’t tell him that I hit her back, / that my father tried holding us apart / like the universe’s saddest referee.

Robin Morgan, “Matrilineal Descent” | Not having spoken for years now, / I know you claim exile from my consciousness. / Yet I wear mourning whole nights through

Juliet Kono, “Homeless” | He says he wants to live with me. / I say I can’t live with him— / boy whose words crash like branches in a rain storm.

Jennifer Chang, “Obedience, or the Lying Tale” | Before me / the field, a loose run of grass. I stay / in the river, Mother, I study escape.

Sandra Lim, “Certainty” | I am not a stupid child. I am not even a child any longer, with her hesitant, then terrible certainty, that loss is tragic, not only pointless.

Truong Tran, “what remains two” | my own mother says it was not meant / to be cruel when cruelty she tells me / is a child’s lips torn from breast as proof / back home the women wear teeth marks

#poetry#compilation#web weaving#chen chen#recommendation#reading list#robin morgan#juliet kono#jennifer chang#sandra lim#truong tran#mothers#family#dysfunction

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Bachofen and more recent supporters of his theory such as G. D. Thomson maintain that a matriarchal or matrilineal order prevailed in Rome's monarchic era (which, by Roman reckoning, extended from 753 to 510 B.C.). They suppose as well that this matriarchal or matrilineal order was first associated with Rome's Sabine component and reached its peak during the Etruscan domination of Rome in the late seventh and sixth centuries B.C. According to such a view, therefore, the esteem granted and formidability attributed to so many well-born women of the republican and early imperial periods, the very opposite of what one might expect from their lack of formal civil rights, constitutes a survival of early "mother right," Sabine and Etruscan in provenance.

Yet the hypothesis that matriarchal or matrilineal elements in Sabine, and in particular Etruscan, culture were absorbed into Roman civilization, though a convenient means of accounting for certain seemingly incongruous features of later republican and early imperial Roman society, poses certain problems. In the first place, the identification and isolation of purely Sabine and Etruscan components in pre-republican Roman culture are not only difficult, but fraught with complications. Scholars differ strongly over when Sabine and Etruscan influence was felt in early, "Latin," Rome, and thus where a particular early Roman practice originated.

One must also consider why many practices, if indeed non-Roman in origin, were adopted. For if Roman society of the mon archic period is to be attributed with its own, native, Latin, practices and institutions, which it gradually combined with those of non-Latin (Sabine) and non-Indo- European (Etruscan) peoples, it presumably incorporated solely those foreign elements which fitted its existing needs and adapted those elements to conform with its own pre-existing attitudes and usages. In fact, two of the so-called Sabine and Etruscan practices which Thomson himself remarks upon as significant "matriarchal" features of monarchic Rome as it is portrayed by classical authors such as Livy—royal succession bya son- in-law and by a daughter's son—are also said, by Livy himself, to have first obtained among the Latins.

At 1.1.9-11 Livy depicts Rome's Trojan forefather Aeneas as able to claim the throne of Latium only after wedding the daughter of its king, Latinus; Livy later represents Aeneas' descendant Romulus and his twin brother Remus as claiming their monarchic rights to found a new city because their mother was daughter of Numitor, rightful king of the Latin city Alba Longa. Thus it would seem likely that if the social importance and political influence ascribed to Roman women of the clas sical period are survivals from the years of Sabine and especially Etruscan hegemony at Rome, then the Romans of those early eras must have found the general Sabine and Etruscan view of women as significant individuals compatible with their own. Furthermore, the fact that a practice based on widespread human familial sentiment (such as the respect for motherhood in monarchic Rome discerned by Bachofen and his adherents) "survives" from an earlier period should imply that the sentiment still obtains to some extent in the later period.

Concern for the origins of women's social significance and political influence in classical Roman times does not, therefore, in itself suffice: the reasons why women continued to be regarded as socially significant and politically influential after the monarchic, and through the classical, era deserve equal attention. Although we have relatively little knowledge of earliest Sabine society outside our later Roman literary sources, we do have a large body of independent evidence on the Etruscans in the late seventh and sixth centuries B.C. and in the several centuries thereafter.

Many Etruscan works of art and inscriptions, largely from their grave goods and cemetery decorations, still exist and reveal much about the Etruscans' lifestyle and values. This evidence, moreover, also calls the theory of Bachofen and his adherents seriously into question: it does not suggest that the Etruscans ever exalted older women by ceding to them positions of political leadership denied to men, or that the Etruscans ever reckoned descent solely through the female line. In other words, the terms "matriarchy," signifying rule by mothers, and "matriliny," meaning the reckoning of ancestral descent through mothers, do not accurately represent the Etruscans' political organization or kinship structure in any period.

Indeed, the term "matriarchy" has no descriptive relevance to the political or the kinship structure of any society in which women do not monopolize (or significantly control) government, but have available to them opportunities for political involvement and influence also open (and in some societies only open) to males. The term "matriliny" is similarly uninformative about any society which values maternal lineage, and mothers themselves, but not to the degree that it discounts or devalues paternal lineage and fathers. Etruscan society seems to have provided women with opportunities for public involvement and to have assigned great value to maternal lineage. The social importance the Etruscans accorded women and the Etruscan emphasis on maternal ancestry have even been, as we have noted, enough to earn them a reputation among certain scholars for belief in the principle of "mother right." But as this discussion has observed and will continue to demonstrate, elite Roman society of classical times displayed these very features as well.

Admittedly, the Etruscans differed considerably from the classical Romans in their mode of identifying women and in their definition of acceptable female behavior. Unlike their Roman counterparts, well-born Etruscan women were given individuating names and often commemorated by indications of both their fathers' and their mothers' names. Tomb paintings and objects document that affluent Etruscan women took part in dancing and athletic exercise and indulged themselves at lavish parties and with elaborate attire, behavior which contrasts with that of Roman women. Such artifacts imply, too, that Etruscan women of high birth, in contrast to aristocratic Roman matrons, were not celebrated for wool-spinning and domestic administration. These differences between Etruscan and classical Roman women are not to be dismissed.

They warrant investigation and explanation—through study of each larger society and its values and, more specifically, of how women were integrated into each entire culture and its institutions and beliefs. But these differences should not be exaggerated, particularly by those who would explain the formidable be havior and image of elite Roman women in the classical era as a survival of early "mother right" connected with the Etruscans. By the same token, superficial similarities between later Roman and earlier Etruscan beliefs and practices relating to women do not automatically establish the former as "Etruscan legacies," nor should they be used to account for other features of republican and imperial Roman civilization; rather, they must be understood in the context of their own culture and its entire social structure.

The argument that behavioral patterns associated with early Roman "mother right" survived into the classical era is most thoroughly demolished, however, by actual examination of Roman society during its earliest years, including those in which Sabine and Etruscan culture would have exerted their greatest influence; such an examination reveals the thoroughly and overwhelmingly patriarchal nature of Roman society of that time. The patriarchal nature of earliest Roman society, moreover, seems to have had its roots in the organization of the Roman family. Testimony about the earliest Romans parative materials is kept to a minimum (and restricted to other ancient cultures kindred with and familiar to the Romans them selves). This study does, however, seek to establish the similarities between Roman upper-class family structure and family-related economic institutions, patterns of political behavior, language, and legends—especially those related, by such authors as Livy, Plutarch, and their sources, with a moralistic, "ideological," purpose—in their emphasis on certain female roles, and to argue for the cultural centrality of one, primal, female familial role to explain these similarities.

- Judith P. Hallett, “The Paradox of Elite Roman Women: Patriarchal Society and Female Formidability.” in Fathers and Daughters in Roman Society: Women and the Elite Family

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

OH MY GOD NO I'm not a kaylor I swear I just read something like that about women who convert on Twitter I wanted to get your opinion about it because it was a whole discussion and thread I found under this girl who talks about feminism

I think like I say questioning anyone’s conversion is problematic. No one asks me who convert why they did it. We shouldn’t do it to women.

Also, again, the thing is a Jewish man’s kids will be Jewish whether or not they are so halachically. And a Jewish woman’s kids will be Jewish whether their dad is or not. So for example Mila and Ashton have chosen for him not to convert because it doesn’t affect their children but they’re raising the kids as Jews and Ashton studied it extensively and does all the Shabbas brochas (blessings) and takes on the Jewish patriarch role even though he isn’t halachically Jewish. It doesn’t matter because the kids still are. If the genders were reversed though, that wouldn’t work and considering Judaism is important to their family I’d imagine they’d have converted too.

Understanding why more women convert is bound to the whole matrilineal descent in Judaism tbh - like it is more important for the mother to be Jewish, but even if the mother isn’t the child will be affected by being Jewish you know, so it just makes sense for a lot of inter-faith couples and I don’t think it’s anti-feminist at all.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

HELLO WHICH IS THE FANFIC WHERE ABED HAS A SISTER WHO LOVES MOTHS i must read

Here’s the link to the fanfic! I don’t know this persons’s tumblr so if anyone does know please @ them!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women and Family in Korean History

Selections from A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present, 3rd ed., by Michael J. Seth, 2020

The status of women in Silla [traditionally 57 BCE--935 CE] was higher than in subsequent periods and perhaps higher than it was in Paekche and Koguryŏ. Much of our knowledge of Silla’s family structure and the role of women, however, remains a matter of speculation. It is believed that the status of women was high compared to most contemporary Asian societies, that men and women mingled freely and participated together in social functions, and that families traced their ancestry along both their father’s and mother’s line. Women were able to succeed as the family head, and failure to produce a son was not grounds for divorce. Three women ascended to the throne—the last was Chinsŏng (r. 887–897)—although only when there was no male heir. Among royalty, about whom much more information is available, girls married between sixteen and twenty, and there was often a considerable difference in ages between partners. No strict rule seems to have existed concerning the use of paternal surnames. Succession was not limited to sons, but also included daughters, sons-in-law, and grandsons by sons and daughters. Equal importance was given to the rank of the father and the mother in determining the status of the child.[6] Kings selected their queens from powerful families. A careful reading of the historical records that were edited in later times suggests that Silla queens may have exercised considerable authority.[7] In all these ways, Korean society at this time differed from later periods, in which the position of women weakened considerably. If the above represents an accurate picture of Silla society, then the pattern of the next 1,000 years of Korean history is one of a steady decline in the status of women, of greater segregation of the sexes, and of a shift to a more patrilineal society.

[...]

As historian Martina Deuchler and others have pointed out, compared to later periods, the social position for women in Koryŏ [918--1392] times was high. Women could inherit property, and an inheritance was divided equally among siblings regardless of gender. A woman’s property was hers and could be passed on to her children. Some women inherited homes and estates. Ownership of property often gave upper-class women considerable independence. Korean women remained to a considerable extent members of their natal families, not those of their husbands. For example, if a woman died without children, her property passed on to her siblings, not to her husband. Wives were not merely servants of their husbands. Their importance was reflected in the practice of conducting marriages in the house of the bride. There was no bride wealth or dowry, and men often resided in their wife’s home after marriage. The two sexes mingled freely. The twelfth-century Chinese traveler Xu Jing was surprised by the ease with which men and women socialized, including even bathing together.[23] Recent studies have clarified this picture of the role of women. In private affairs such as marriage, care of parents, and inheritance of land, women had equal rights with men, but they were excluded from public affairs.[24]

We do not yet have a clear picture of marriage in Koryŏ.[25] Evidence suggests that marriage rules were loose. Divorce was possible, but seems to have been uncommon; separation may have been more common. Koreans may have also practiced short-term or temporary marriages; however, the evidence of this is unclear. Remarriage of widows was an accepted practice. Marriage between close kin and within the village was also probably common. Later Korean society was characterized by extreme endogamy in which marriage between people of even the remotest relationship was prohibited, but this was not yet the case in Koryŏ times. Plural marriages may have been frequent among the aristocracy. Xu Jing said that it was common for a man to have three or four wives. Concubinage existed, but it is not known how customary it was. Evidence suggests that upper-class men married at about twenty and women at about seventeen. Men lived with their wife’s family until about the age of thirty. Widows as well as widowers appear to have kept their children. All this is a sharp contrast with later Korean practices (see chapter 7).

The Koryŏ elite was not strictly patrilineal. Instead, members of the elite traced their families along their matrilineal lines as well. This gave importance to the wife’s family, since her status helped to determine that of her children. Although high status and rights of women in Koryŏ were in contrast to later Korean practice, in many ways it was similar to Japan in the Heian period (794–1192). Much less is known about either Sillan or early Koryŏ society than about Heian Japan, but it is likely that the two societies shared a number of common practices relating to family, gender, and marriage. It is possible that these practices may, in fact, be related to the common origins of the two peoples. This is still a matter of speculation; further study is needed before the relationship between Korea and Japan is clearly understood.

Some changes took place over the nearly five centuries of the Koryŏ period. The adoption of the civil examination system in the tenth century led to careful records of family relations. At the same time, the strengthening of Chinese influences resulted in the gradual adoption of the Chinese practice of forbidding marriage among members of patrilineal kin. As Koreans began to place more importance on direct male descent and the Confucian ideas of the subordination of women to men became more accepted, the position of women declined. The state, for example, enacted laws prohibiting a wife from leaving her husband without his consent. Most major changes in family and gender relations, however, took place only after the Koryŏ period.

[...]

Korea during the Chosŏn (Yi dynasty) period became in many ways a model Confucian society. Confucian ideas shaped family and society in profound ways. Although China was the home of Neo-Confucian ideals and they were embraced by many in Japan and Vietnam, nowhere else was there such a conscientious and consistent attempt to remold society in conformity to them. The zeal and persistence by which Koreans strove to reshape their society in accordance with Neo-Confucian ideals helped to set them apart from their East Asian neighbors. These efforts initially began at the upper levels of society, but by the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries Neo-Confucian norms had prevailed, if to a somewhat lesser degree, among commoners. As Neo-Confucian values penetrated throughout all levels of society, they helped bind the Korean people together as members of a single culture even while sharp class divisions remained. While it moved Korea closer to many Chinese cultural norms, Confucianization was also a creative process of adapting the ideals that originated in China to indigenous social practices. Indeed, it was during this period that many distinctive features of Korean culture, such as its unique writing system, emerged.

The basic ideals of Confucianism centered on proper social relationships. Three cardinal principles (samgang) guided these social relationships: loyalty (ch’ung) of subjects to their ruler, filial piety (hyo) toward one’s parents, and maintaining distinction (yŏl) between men and women. Distinction meant that women had to display chastity, obedience, and faithfulness. Another Confucian formulation that defined the relationships that held society together was the five ethical norms (oryun): ŭi (righteousness and justice), which governed the conduct between ruler and ministers (subjects); ch’in (cordiality or closeness) between parents and children; pyŏl (distinction) between husbands and wives; sŏ (order) between elders and juniors; and sin (trust) between friends.[1] The ethical norms of Confucianism emphasized the importance of family relations, the hierarchical nature of society, the necessity for order and harmony, respect for elders and for authority, the importance of a clear distinction between men and women, and the subordinate status of women. Neo-Confucianists taught that each individual was to strive to cultivate his or her virtue. This was regarded as a lifelong task that involved sincere and persistent effort. Neo-Confucianists placed great importance on rituals and ceremonies, on honoring one’s ancestors, on formality and correctness in relationships, on constant study of the classics as a guide to a virtuous life, and on the importance of public service. They valued frugality, thrift, hard work, and courteousness, along with refraining from indulgence in immoderate behavior. Neo-Confucianists could be prudes, disdainful of spontaneous or sensuous behavior.

It was a philosophy that emphasized rank and status; it was important for everyone to know his or her place and role in society. Concern about rank and hierarchy had always been a feature of Korean society, but Neo-Confucian thought gave that concern ethical purpose. The Korean language reinforced rank consciousness. Lower-class people addressed upper-class persons with honorific forms that Koreans call chondaeŏ or chondaemal. As they addressed their superiors, their sentences concluded with verbal endings that indicated levels of deference. The language contained many synonyms reserved for respectful usage. Superiors in age or social status spoke in turn to their inferiors in a speech style devoid of the elaborate honorific endings and special honorific terms, which came to be called panmal. This use of elaborate speech styles indicating levels of deference, intimacy, and formality is still part of the Korean language.

The Family

Family and lineage were fundamental to the Korean Confucian order. Lineage refers to those people who directly trace their origins to a common ancestor. In Korea these lineages were called munjung. Only those who were in the direct line traced through the eldest son or nearest male relative belonged to a lineage. To keep track of lineage, Koreans began to keep chokpo, books where births, marriages, and deaths were recorded over the generations. This started to become a common practice in the fifteenth century and eventually became a universal custom, so that most Koreans, even today, can usually trace their ancestry back many generations. Families eventually began to keep pulch’ŏnjiwi (never removed tablets) with the names of their immediate ancestors at the home of the lineage heir, normally the eldest son. Many of the ceremonies and practices associated with lineage found their way into the law code, the Kyŏngguk taejŏn, compiled in 1469. Laws required all Koreans to perform the rites to their ancestors known as chesa. In the chesa ancestral rites family members pay homage to chosang (ancestors). This emphasized that the ties of kinship extended to include the dead as well as the living. Ancestral rites became extremely important in establishing family ties. There were three basic types of chesa: kije, or death anniversary commemorations, which were performed at midnight on the eve of the ancestor’s death day; ch’arye, or holiday commemorations, which were performed on certain holidays; and myoje, or graveside commemorations performed on visits to a family member or to an ancestor’s grave (myo).

At the kije and ch’arye rites, the family members offered food and drink to the ancestral spirits. The rites came to symbolize the importance of maintaining order and properly adhering to rituals. Every aspect of the rituals followed a formal procedure. Food had to be arranged on an altar in a special order: fruit in the front row; then vegetables, soups, and meats; rice and thick soups; and spoons and chopsticks in the back. Red fruit was placed on the east and white on the west. Incense was placed in front of the food table, and a tray for wine was placed in front of the incense. Rites were performed by the eldest direct male relative, who began the ceremonies by kneeling and burning incense and then pouring three cups of wine. Others, generally according to rank, followed, prostrating themselves with their heads touching the floor three times. The eldest male then took the cup of wine after rotating it three times in the incense smoke. When the wine offering was completed the family members left and allowed the ancestor to eat. The men returned and bowed and the food was then served to the family. These rituals came to be performed exclusively by men. Chesa rituals emphasized the importance of family, lineage, and maintaining a sense of order and propriety.

Marriage in Chosŏn Korea was characterized by extreme exogamy and a strong sense of status. Koreans generally married outside their communities and were prohibited from marrying anyone within the same lineage, even if that lineage contained up to hundreds of thousands of members, as the largest ones did. Yet the concern for status meant that marriages remained confined within a social class. In early Koryŏ times, marriages between close kin and within a village were probably common, but they became less so in subsequent centuries. The adoption of the civil examination system in the tenth century led to careful records of family relations and to the strengthening of Chinese influences forbidding marriage of patrilineal kin. However, in Koryŏ such marriages still took place. During the Chosŏn period the strict rules prohibiting kin marriages were enforced. Men and women married at younger ages than Western Europeans but not as early as in many Asian societies. In 1471, minimum ages of fifteen and fourteen were legislated for men and women, respectively. Men generally married between sixteen and thirty years of age and women fourteen to twenty; the age gap between husband and wife was often considerable. Commoners often married at younger ages than yangban [aristocracy].

Weddings underwent changes in Korea during the Chosŏn period as a result of the impact of Neo-Confucianism. Zhu Xi’s Family Rituals (Chinese: Jiali, Korean: Karye) became the basis for rules governing marriage ceremonies and practices. Koreans did not always blindly adhere to them, and wedding practices were modified somewhat to conform to Korean customs. For example, Koreans had traditionally married at the bride’s home. But Zhu Xi and other authors stated that it should be done at the groom’s home. Scholars and officials debated whether to follow Chinese custom or kuksok (national practice). A compromise was worked out in which part of the ceremony was performed at the bride’s home, after which the couple proceeded to the groom’s family home to complete the wedding. To this day when marrying, Korean women say they are going to their groom’s father’s house (sijip kanda) and men say they are going to their wife’s father’s house (changga kanda). In Koryŏ times, many if not most newlyweds resided at the wife’s family residence. This custom, contrary to notions of patrilineal family structure, gradually died out, and brides moved into their husband’s home. In many cases, however, young couples lived with whomever’s family was nearest or with whichever parents needed care or had land available to farm.

A variation of marriage custom was the minmyŏnuri, a girl bride who entered the house as a child, often at the age of six or seven. Koreans never felt entirely comfortable with this custom, boasting that, unlike the Chinese at least, they did not take girls at infancy.[2] The girl bride would be ritually sent back to her home to reenter upon marriage, although this was not always practiced. The Yi government disapproved of the custom and set minimum marriage ages, but these were not enforced. Child marriages were practiced mainly by the poorer members of society who needed the child labor and who could not afford costly weddings. Often the family of the bride could not afford a dowry. One advantage of child marriages was that the girl would be trained to be an obedient daughter-in-law, but in general it was a source of shame and a sign of poverty. Many grooms who were too poor to obtain a bride found this to be their only option. It was not unusual for the groom to be a fully grown adult so that an age gap of as much as thirty years between husband and wife was possible. Korean tales talk of the abuse these child brides received from their mothers-in-law. No doubt for some life was miserable. For much the same economic reasons, some families had terilsawi or boy child grooms, although this was less common.

Great emphasis was placed on direct male descent, usually through the changja (first son). While this was always important in Korea, it was reinforced by Neo-Confucian thought, especially the influence of Zhu Xi. So important was direct male descent that even the posthumous adoption of a male heir (usually a close male relative) was necessary if a man died before leaving a male offspring. Men also took secondary wives, not just to satisfy their lust but to ensure they had male offspring. Inheritance patterns in Korea differed from those of its neighbors. While in China land was divided equally among sons, and in Japan all rights went to a sole heir, in Korea the trend during the Yi was to exclude daughters from inheritance and to give the largest portion to the first son, although all sons had the right to some property. This meant that most of a family’s property was kept intact and not divided, or at least kept in the lineage.

In short, Korean families during the Yi dynasty became increasingly patriarchal in that the authority of the males was enhanced. They became patrilineal in organization in that property was inherited through males, and that descent and the status that came with it was traced primarily through direct father-to-son or nearest male relative lines. The habit of residence in the groom’s family home after marriage reinforced male dominance. Families and lineages were exclusive; nonmembers could not be adopted into families. Nor could they join lineages, although disgraced members such as traitors and criminals could be expelled from them. Family and lineage truly mattered in Korea, as evidenced by the huge number of printed genealogies produced, perhaps unmatched in volume per capita anywhere else in the world.

Women During the Yi Dynasty

The status of women declined during the Chosŏn period. This can be attributed at least in part, if not primarily, to the fact that Neo-Confucianists stressed direct male descent and the subordination of women to men. Women were urged to obey their fathers in youth, their husbands in marriage, and their sons in old age. Books written for women emphasized virtue, chastity, submission to one’s husband, devotion to in-laws, frugality, and diligence. Moral literature, a great deal of which was published under the Yi, emphasized that women should be chaste, faithful, obedient to husbands, obedient to in-laws, frugal, and filial. Some of this literature was published by the state. To promote these values, the state in 1434 awarded honors to women for virtue. Literacy was very low among women, since the village and county schools admitted only men. The small proportion who could write, perhaps amounting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to only 3 or 4 percent at the most, generally did so in han’gŭl, rather than in the more prestigious Chinese characters.

The decline in status was gradual. Households headed by women disappeared early in the Yi dynasty, but women still inherited property until the seventeenth century. Widows were no longer allowed to remarry, since they were supposed to be loyal to their husbands even after their partner’s death. As the marriage customs shifted from earlier practices, brides usually left their families after marriage. A daughter was a todungnyŏ (“robber woman”), since she carried away the family wealth when she married. A married daughter became a ch’ulga oein (“one who left the household and became a stranger”).[3] This contributed to the practice of reducing or eliminating a daughter’s share of her inheritance. Since the daughter was thought to leave her family, there was less reason to bequeath a portion of the family estate to her. Women could not divorce men, but men could divorce women under the principle called ch’ilgŏjiak (seven grounds for divorce), which legitimized the grounds for divorce. The seven grounds for divorce were disobedience to parents-in-law, failure to bear a son, adultery, jealousy, hereditary disease, talkativeness, and larceny. So associated were women with their families that they were generally referred to by their relationship to their male family members rather than by their name. It has been suggested that by late Chosŏn, women became “nameless entities,” being referred to as “the wife of” or as the “mother of (son’s name).” They had, in other words, not only lost their rights to divorce, to property, to participating in public life, they had also lost any identity of their own.

Women could no longer freely mix with men socially, and their lives were restricted in many ways. Nae-oe pǒp, inner-outer laws, sought to keep the sexes strictly separate. The official legal code, the Kyŏngguk Taejŏn, forbade upper-class women from playing games and from partying outdoors, with penalties of up to 100 lashes. Horse riding, a common activity among upper-class Koryŏ women, was forbidden by law in 1402. Women had to seek the permission of husbands or family heads before participating in social activities. Upper-class women were not allowed to attend services at Buddhist temples or any public festivals.[4] In later Chosŏn, women in Seoul were allowed in the street only during men’s curfew hours from 9 p.m. to 2 a.m. At other times it became customary for women to wear veils when entering the street. The segregation and restriction of women became reflected in the architecture of the Korean home, which was divided between the sarang ch’ae, the outer section for men, and the anch’ae, the inner section of the house for women, also called the anbang (inner room). Even poor families often had three rooms: one for men, one for women, and the kitchen. Husbands and wives often lived virtually apart in their own home. Separation of religious functions occurred as well, with the women in charge of kosa, offerings to household gods, and the men chesa, Confucian rites to the ancestors. Unlike in China, women were excluded from the rites to the ancestors. In Korea there was a clear gender division in ritual responsibilities.

Particularly tragic was the position of widows. Since a woman was not allowed to remarry, or head a household, once her husband died she became an inconvenience for her family. There were stories of widows being pressured to commit suicide, but this was probably rare. A widow was sometimes called a mimangin (a person who has not died yet). Among commoners and outcastes widows were sometimes married off to a poor man, sometimes to a widower who needed a wife but could not afford a marriage. The man would enter the house and carry out the woman, supposedly in a big sack, resulting in what was sometimes referred to as a “sack marriage.” This might be arranged by the widow’s family against her will.[5] Also difficult was the life of women in a household where a man took a concubine. This practice was an opportunity for a poor slave or commoner woman to enter an upper-class household. But her life could be made difficult by the jealous first wife and her children, and by the stain of illegitimacy given to her children (see below). First wives could also be made miserable by the entry of a new younger wife with whom they had to compete for their husband’s attention.

The same Confucian demand on loyalty and chastity that made remarriage unacceptable resulted in the custom of presenting a woman with a p’aedo, a suicide knife. This custom, which began among the elite, became common to all social classes in the southern regions. There were reported cases of women using the knife to protect themselves from attackers. In one such case, a government slave girl, Tŏkchi, used her p’aedo to kill a number of Japanese who attempted to rape her during the sixteenth-century invasions. But the purpose of the knife was for a woman to protect her virtue by committing suicide. A particularly sharp knife was called a chamal p’aedo after another slave girl, who after being embraced by her drunken master always kept her knife sharpened.[6] A woman had to not only protect her honor but, most importantly, protect her family from even the slightest hint of scandal. Sometimes even rumors of an indiscretion were enough for a woman to be pressured to commit suicide for the sake of her family’s reputation.

The sign of a married woman was the tchok, long braided hair coiled at the nape and held together with a pinyŏ, a long pin. Single women wore their long hair unpinned. Ideally women were kept from public view, secluded in their women’s quarters and venturing out only in screened sedan chairs or at night. In reality, only the upper class could afford this. Rural women worked in the fields, participating in all the tasks except plowing and threshing, which were men’s work. Women could not engage in business, but women’s loan associations, called kye, were an important source of income for rural women. Commoner and low-caste women mixed with men at festivals. The separate existence of men and women was an ideal most honored at the upper reaches of society.

There were also some exceptions to the restricted roles of women. Mudang (women shamans) were an important part of life since at least Silla. During Chosŏn times the great majority of shamans were women, although their social status declined as a result of the official Confucian disdain of traditional religions. Some women became entertainers. These were generally from outcaste and slave families from whom attractive young girls were often purchased to be trained as entertainers known in Chosŏn times as kisaeng (see photo 7.1).

Women prevailed in some performing arts, such as singers in the nineteenth-century dramatic form p’ansori.

Perhaps the most interesting exception to the restricted lives of women were the kisaeng. The kisaeng were carefully trained female entertainers similar to the Chinese singsong girls and the Japanese geisha. Kisaeng often came from the slaves. Attractive ones would be taught to read and write, appreciate poetry, and perform on musical instruments so that they could entertain men, especially yangban. Since the lives of men and women were increasingly segregated, the kisaeng offered men a chance to enjoy the company of women who were not only attractive but able to engage in learned conversation and witty banter. There were also common prostitutes; however, the kisaeng were considered more virtuous as well as highly educated, fitting companions for upper-class men. Kisaeng were able to engage in conversation with men and be intellectual as well as romantic companions to men in a way that good, virtuous Confucian wives could not. Some kisaeng were official kisaeng, recruited and employed by the state. These were carefully trained in government-regulated houses. During the early dynasty about 100 kisaeng were recruited every three years for the court while others were trained and sent to provincial capitals.

Most kisaeng were privately employed by the hundreds of kisaeng houses throughout the country. There were, however, also medical kisaeng who besides their duty entertaining men also served to treat upper-class women, since women of good families were unable to see male doctors who were not related to them. Others were also trained to sew royal garments. Kisaeng, although never entirely respectable, were often admired and loved by men. Some were celebrated for their wit and intellect as well as their beauty and charm. A few talented kisaeng won fame for their artistic and literary accomplishments, such as the sixteenth-century poet Hwang Chin-i (see below). Another, Non’gae, according to legend, became a heroine when she jumped in the Nam River with a Japanese general during the Hideyoshi invasions. But these were exceptions; most kisaeng led humble lives in which the best they could hope for was to be some wealthy man’s concubine.

[...]

An interesting legacy of Chosŏn was women’s literature. In recent years scholars have rediscovered much of this large body of feminine writing. The percentage of women who were literate was small, since even yangban girls were discouraged from learning. Nonetheless, a small number of women became quite accomplished in letters. Lady Yun, mother of Kim Man-jung (1637–1692), is said to have tutored her two sons to pass the civil exams. Lady Sin Saimdang (1504–1551), mother of Yi I (Yulgok), wrote many works in Chinese. Hŏ Nansŏrhŏn (1563–1589), a beautiful and highly intelligent daughter of a high-ranking official, was so talented as a youth that she attracted the attention of well-known poets who tutored her. Tragically she died at the age of twenty-six and destroyed many of her poems before her death. Her famous brother, Hŏ Kyun, collected what remained. These proved to be enough to earn her a reputation as an accomplished poet not only in Korea but also in China. Another distinguished woman writer was Song Tŏk-pong (1521?–1579), the daughter of a high official who became famous as a poet and was the author of the prose work the Diary of Miam (Miam ilgi).[17] Kisaeng such as Hwang Chin-i were often accomplished poets as well.

As in Japan, Korean women wrote primarily in indigenous script while men stuck to the more prestigious Chinese characters to express themselves. Women, if they learned to write, generally wrote in han’gŭl, which was regarded as fitting for them. Han’gŭl, in fact, was sometimes referred to as amgŭl (female letters). Women, following cultural expectations, generally wrote about family matters. But within these restrictions Korean women produced kyuban or naebang kasa (inner-room kasa). These originated in the eighteenth century and were largely anonymous. They included admonitions addressed to daughters and granddaughters by mothers and grandmothers on the occasion of a young woman’s marriage and departure from home. Young brides would arrive with these kasa copied on rolls of paper. They would pass them to their daughters with their own kasa added. Other inner-room kasa dealt with the success of their sons in taking exams, complaints about their lives, and seasonal gatherings of women relatives.[18]

Another genre of women’s literature was palace literature written by court ladies about the people and intrigues of court. A large body of this literature, much of it still not well studied, survives. Among the best known is the anonymously authored Kyech’uk ilgi (Diary of the Year of the Black Ox, 1613), the story of Sŏnjo’s second queen, Inmok. Queen Inmok is portrayed as a virtuous lady who falls victim to palace politics and jealousies. She struggles to protect her son and is imprisoned by Kwanghaegun. The tale ends when the doors of the palace where she is imprisoned are suddenly opened following Kwanghaegun’s over-throw.[19] Another work, Inhyŏn Wanghu chŏn (Life of Queen Inhyŏn), tells the virtuous life of Queen Inhyŏn, who married King Sukchong in 1681. She too is victimized at the hands of an evil rival, Lady Chang. Today the most read of these palace works is the Hanjungnok (Records Written in Silence) by Lady Hyegyŏng (1735–1815). This is the autobiography of the wife of the ill-fated crown prince Changhŏn. Written in the form of four memoirs, it is a realistic and in most respects accurate story of her mistreatment at court, the tragedy of her husband’s mental illness and death, and the sufferings of her natal family at the hands of political enemies. Her memoirs are a literary masterpiece, and because of their honesty and her astute insights, they are a valuable window into court life in the eighteenth century. Biographical writings by women in East Asia are very rare, and one by a woman of such high intelligence so close to the center of political life is especially important.[20]

[...]

Few social changes [in the early modern period] marked a greater break with tradition than those that concerned women. Many Korena women embraced new ideas and opportunities presented by a modernizing society. Korean progressives in the late nineteenth century saw the humble status of Korean women as symptomatic of the country's low level of civilization. The Kabo Reforms [1894-1896] had abolished some of the legal restrictions on women. They also abolished child marriage and ended the prohibition on widows to remarry. The issues of establishing greater equality for women, begun by the tiny number of Koreans exposed to the outside world in the 1890s, was embraced by much of the intellectual community in colonial times. Many Koreans blamed the Confucian concept of namjon yŏbi (revere men, despise women) as emblematic of both the country's backwardness and its past uncritical adoption of Chinese customs. Of particular concern was the exclusion of women from formal education. They noted that girls attended schools in Western countries and that Japan had drawn up plans in the 1870s to make basic education universal and compulsory for girls as well as boys. An early proponent of women's' education was Sŏ Chae-p'il, whose editorial in the Tongnip sinmun on April 21, 1896, called for equal education for men and women to promote social equality and strengthen the nation. In another editorial in September that year, he argued that gender relations were a mark of a nation's civilization. Conservatives in the late Chosŏn government were less sympathetic to the need for women's education. A petition to the king by a group of women from yangban families to establish a girls' school was ignored.[25] Women's education was established by American missionaries, not Koreans. After an initial slow start, many families began sending their daughters to these new schools, and the enthusiasm for education among Korean women was commented on by foreign missionaries. Women graduates of these schools became active in patriotic organizations, and thousands of women participated in the March First Movement [in 1919]. It was only during the 1920s, however, that the women's movement became a major force in Korea. One of its important figures was Kim Maria. Educated in Tokyo, she formed in April 1919 the Taehan Aeguk Puinhoe (Korean Patriotic Women's Society), an organization to promote national self-determination. The organization worked with the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai and in 1920 claimed some 2,000 members. The activities of this and other, mostly Christian, women's groups helped win respect for women among Korean intellectuals.

In the 1920s men and women participated in discussions about the role of women and gender relations. Feminists included Kim Wŏn-ju, who published Sin yŏja (New Woman); artist Na Hye-sŏk (1896–1948), who wrote for Yŏja kye (Women’s World); and the poet Kim Myŏng-sun. Some members of this small class of women led lives daringly defiant of tradition. They wore Western-style clothes with short skirts and bobbed hair, socialized in public, advocated free love and the right to divorce, and rejected the confinement of women to the roles of housewife and mother. These ideas, however, were too radical for Koreans, including male intellectuals. Moderate nationalists called for an educated, healthy woman who role in society was very much like the "wise mother, good wife" (hyŏnmo yangch’ŏ) ideal promoted by the Japanese government; meanwhile, leftist male nationalists argued for the need to subordinate gender issues to those of class.

Two individuals exemplify this new small class of “modern” women. One is Kim Hwal-lan, known to Westerners as Helen Kim. Born in 1899 to Christian parents in Inch’ŏn, she attended mission schools, became active in the YWCA, went on to Boston University, and received a PhD from Teachers College of Columbia University in 1930. After returning, she became president of Ewha College, the most prestigious school of higher education for women in Korea, a position she held from 1939 to 1961, except for a brief period (1944 to 1945) when the school was shut down by the Japanese. Pak Kyŏng-wŏn (1901–1933), daughter of a rich farmer, attended an industrial arts school in Japan and took a job as a technician in the silk reeling industry, an industry dominated by women workers. She then returned to Japan to learn to become a driver, a rarity for a woman, and then became one of the few women to attend an aviation school. Korea’s first woman aviator, she won a number of flying competitions in Japan before perishing in a flight back to her home in Korea.[26]

The women's movement was quite political, since most writers linked the liberation of women with national liberation. While this may have made the belief in women's rights and equality more acceptable to educated Koreans, it meant that feminists subordinated their own social agenda to the nationalist political agenda. It also meant that the women's movement followed the general split between moderate, gradualist reformers and radical leftists that characterized most political and intellectual activity from the early 1920s. Moderate women reformers were associated with the YWCA and various church and moderate patriotic associations, while some thirty women with socialist and Communist leanings established a more radical group, Chosŏn Yŏsŏng Tonguhoe (Korean Women's Friendship Society) in 1924. As part of the united front, in 1927, moderate and radical women worked together to organize the Kŭnuhoe (Friends of the Rose Sharon). By 1929, the Kŭnuhoe had 2,970 members, including 260 in Tokyo.[27]

The colonial legacy for Korean women was mixed. In many ways the "wise mother, good wife" concept promoted by the Japanese and embraced by much of society reinforced the traditional ideas of a sharply defined domestic "inner" sphere for women and "outer" sphere of public life form men. Yet as Sonja Kim writes, this domestic space for women was "infused with new conceptualizations of equality, rights, and humanity."[28] For the vast majority of Korean women, their traditional subordinate social status remained unchanged, but the emergence of a small number of politically active and assertive women among the educated was an important precursor of more radical changes that would take place after 1945.

[...]

An extreme form of coercion [during the wartime colonial period] was the comfort women, or comfort girls. These were young Korean girls who were either recruited or forcibly enrolled as sex slaves to serve the Japanese troops. The so-called comfort girls included Filipinas and Chinese, but most were Koreans. Many of these girls were recruited under false pretenses. They or their parents were told that they were to be given well-paying jobs. In practice, they were treated miserably. After the war, these girls returned home disgraced and were forced to hide their past or live lives as unmarried and unwanted women. Between 100,000 and 200,000 Koreans became comfort women. One examples was Mun Ok-ju, an eighteen-year-old woman from a poor family of casual laborers in Taegu, in southwestern Korea, who was offered "a good job in a restaurant" by two civilian recruiters. Lured by the promise of a good salary to support her family, she went along with a group of seventeen other young women between the ages of fifteen and twenty-one who were shipped off to Burma, where she "serviced" thirty men a day under conditions of virtual imprisonment. Five of the girls in her group died or committed suicide.[38]

The abuse of the comfort women has become one of the most contentious issues in colonial history. In many ways it symbolizes the brutality and exploitation of Japanese colonialism at its worst. It was only one way Koreans were victimized. Koreans also suffered from Allied bombing while working in Japan, for example. Among the more than 2 million Koreans working in wartime Japan, at least 10,000 died form the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[39]

[...]

One of the revolutionary changes the North Korean Communists introduced was the concept of gender equality. Even the sense of womanhood as an identity was an important innovation in the conservative Confucian Korean society. Women enjoyed equality in education and, at least legally, in pay. Women could share equal inheritance, divorce was made easier, taking of concubines was outlawed, and all occupations were in theory open to women.

Women entered the workforce in large numbers. While the ideology of gender equality encouraged this, the prime motivation was a labor shortage. The labor shortage was especially acute after 1953 and remained a problem since so many young men were in the military and because economic growth relied on labor inputs rather than on improving productivity. In 1958, the Cabinet issued a resolution calling for women to join the workforce. Women who did not work were penalized by receiving smaller rations. The effort to free women for labor was accelerated with the 1976 Law on the Nursing and Upbringing of Children. This called for the creation of 60,000 kindergartens and pre-kindergartens that could accommodate three and a half million children virtually all in this age-group.[23] The day care centers also served the function of indoctrinating the young at an early age. They became a great source of pride; a visit to a model day care center was part of the standard tour for foreign visitors.

Another purpose of day care centers was to free women for the workforce. By the 1970s women made up nearly half the labor force, including 70 percent in light industry and 15 percent in heavy industry.[24] But North Koreans were still conservative enough that women were expected to take care of the housework, to cook for their families, and raise children. Married women were often let out of work early to collect children and prepare dinner. According to the 1976 law, women with children under thirteen were to be let out two hours early but paid for eight hours.[25] Most of the jobs filled by women were low-paid, menial ones. Few women enjoyed high-status jobs. It was rare for them to hold jobs as managers. Many were schoolteachers, but by one estimate only 15 percent were university professors. One-fifth of the delegates to the Supreme Peoples' Assembly, the powerless legislature, were women, but there were few women in top positions. The former Soviet intelligence officer Pak Chŏng-ae stood out, until she was purge in the 1960s. Hŏ Chŏng-suk, daughter of prominent leftist intellectual Hŏ Hŏn, served as Minister of Justice for a while, but she too was purged in the early 1960s.[26] Later, Kim Jong Il's sister Kim Kyŏng-hŭi wielded some power, but mainly through her husband, Chang Sŏng-t’aek.

Marriages were commonly arranged using the Korean custom of a chungmae or matchmaker, much as was done in the South. By the 1980s love matches were becoming more common, again reflecting a pattern of change similar to North Korea’s modernizing neighbors.[27] Visitors to North Korea noticed the change, with more young couples appearing together in public. But in many respects it was a puritanical society with premarital sexual relations strongly discouraged. The Law of Equality between the Sexes in 1946 made divorce by mutual consent extremely easy, and for a decade divorce was fairly common. This was a major break from the past. But in the mid-1950s, people were required to go to a People’s Court, pay a high fee, and then adhere to a period of reconciliation. As a result divorce once again became uncommon.[28] Family bonds, between husband and wife and especially between parent and child, came under official praise to an extent not found in other Communist states. The 1972 constitution stated, “It is strongly affirmed that families are the cells of society and shall be well taken care of by the State.”[29] The nuclear family was idealized and supported.

The birth rate was quite high in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, then fell. Partly this was due to government efforts and partly it was part of the normal demographic transition as the country became more industrialized, urbanized, and better schooled. Early marriages were banned. In 1971 the marriage age was recommended at twenty-eight for women and thirty for men. The long years of military service, small apartments, and the entry of women in the workforce all contributed to a decline in the birth rate. By 1990, the birth rate had fallen to the point that the ban on early marriages was lifted.[30]

[...]

The democratization of South Korea was part of a broad social and cultural change that included the rise of the middle class, of an industrial working class, and of Christianity, and the spread of egalitarian ideals. Another important component of the social and cultural change was the movement for greater legal and social equality for women. At first, attitudes about the role of women in society and the nature of the family changed slowly. After liberation, many South Korean officials and intellectuals were more concerned about preserving or restoring what they sometimes called "laudable customs and conduct" (mip'ung yangsok).[27] In part this was a reaction to the attempts by the colonial authorities to modify the Korean family structures to make it conform to Japanese practice.[28] In a nationalist-traditional response, when the South Korean government created the civil law code in the 1950s, the parts that governed family relations, known as the Family Law, were very conservative, adhering to a traditional patrilineal and patriarchal family structure. It included the prohibition of marriage between people with the same surnames and the same pon'gwan; it not only obligated the eldest son to head the extended family but gave him a greater share of inheritance. Women were excluded from heading households and received less inheritance, and at marriage they were required to become legally part of their husbands' family. In divorce, which was uncommon, men generally received custody of children. Maintaining these practices was important, it was argued, to preserve the essential nature of Korea's cultural traditions.