#societally impaired

Text

a certain type of (typically white lower support needs speaking) autistic people: autism is not a disorder because there’s nothing wrong with me and a disorder implies there’s something wrong with me that needs to be cured😫😫people treat me bad because they see it as a disorder instead of the correct thing of difference or a neurotype!!!

half of this type of people: autism is not a disability because there’s nothing wrong with autism i’m not disabled i can do everything just like a nondisabled person and disability is Bad and i’m not bad

(which. disability is not a bad word and all but i at least applaud you for the consistency??)

other half of this group, somehow: autism is a disability because autism is disabling and there’s nothing wrong with disability! disability isn’t inherently bad it’s how society treat us that disables us!!! —but autism is still not a disorder! it’s not a disorder it’s a disability and a neurotype!

(disability isn’t bad but this group also perpetuated a lot of misinformation about the social model. i only have to fight them on one subject (autism as disorder) instead of two (autism as disability and disorder) but somehow this group is even more frustrating to deal with because the sheer cognitive dissonance is going to explode my brains. like so you can separate disability from societal ableism but you can’t separate disorder from societal ableism???)

bonus. all of them: *will come onto the post of a higher support needs autistic person talking about why autism is a disability AND a disorder and half complain half dissecting why some (lower support needs) autistic people are so fucking keen on speaking over higher support needs autistic experience. and then have the fucking audacity to say “well i don’t think autism is a disorder because” and then performatively say “if i misunderstand you’re welcome to educate me” as if the entire fucking original post isn’t an education and as if i owe explaining my entire experience to you*

for the record and for the last fucking time (narrator: it would not be the last time). disorder is not a bad word it’s not an inherently wrong thing it’s not a bad thing and if you think it is please for the love of god work on your internalized ableism instead of externalizing it to a more marginalized person. yes the construction of disorders especially in the realm of psychiatry is shit and a mess but that doesn’t mean what you think it means please. a disability a disorder an impairment is limiting by definition it’s a fact it can be neutral it doesn’t have to inherently mean the societal stigma associated with it is true. a disorder and how society and ableist people treat that disorder is heavily intertwined but the second is not inherent to the first.

if you don’t see your autism as a disorder i’m not going to argue over your own experience but stop fucking implying or straight up saying all autism is not a disorder. stop trying to erase the disorder part of autism spectrum disorder. please get out of your tunnel vision and actually shut up and listen to higher support needs / nonspeaking autistics for once in your life without adding any of your comments please.

disability is not an inherently bad thing. disorder is not an inherently bad thing. impairment is not an inherently bad thing.

#actually autistic#actuallyautistic#autism#autistic#high support needs#medium support needs#low support needs#anger tw#swearing tw#loaf screm#jesus christ you all test my very thin patience

712 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thing to remember if you are writing anything involving class and working class people, including game design: poverty is a major cause of AND a major result of disability and chronic illness.

If you write something where every working class person, every person who comes from a working class background, or every poor person, is healthy and physically strong, and just as much or more so if you bake that into a game system by giving people from those backgrounds high Health or Strength stats, you are making an active *choice* to erase a substantial part of the experience of and results of poverty.

Disabled people exist *everywhere*. In every setting - even when there’s magical healing or nanobots or whatever, frankly, erasure of disabled people and the experience of disability is an active narrative choice to erase us. So we *certainly* exist in *every* real world present-day and historical setting, and the fact that you don’t think so is due to active cultural erasure of disabled people and the experience of disability.

While disability is *absolutely* present in every strata of society, the experiences of disability and poverty are deeply and inherently entwined. Given that the vast majority of people are workers, and primarily physical workers throughout history - and if you don’t think disability massively impairs your ability to do call centre work, let alone food service, care work, retail work, or most of the other low-paid jobs in our current service economy, even if they are not habitually classified as heavy physical work, you need to massively expand your understanding of what disability actually is.

Poverty is generational in all sorts of ways, but one of them is that gestational and childhood poverty affects a person for their entire life. There are so many illnesses that one is predisposed to by inadequate nutrition during gestation and childhood, or by environmental pollution during those times (most likely in poverty-stricken areas). Disability and illness in parents and family members so often sees young children go without essentials and older ones forced into forgoing education and opportunities so they can care for family members or enter paid work. It’s a generational cycle that has held depressingly true in urban and rural areas, and that’s before even considering the impact of genetic illnesses and predisposition to illnesses.

Not to mention that a great deal of neurodivergence is incredibly disabling in every strata of society - yes, bits of it can be very advantageous in certain places, jobs, roles and positions, but the *universality* of punishment for not intuiting the subtle social rules of place and social environment again and again means most ND folk end up with a massive burden of trauma by adulthood. On top of the poverty that means in loss of access to paid work and other opportunities, trauma is incredibly shitty for your health.

Yeah; it might not be “fun” to write about or depict. But by failing to do so you are actively perpetuating the idea that the class system, whatever it is, is “just”. That poorest people do the jobs they do because they are “best suited for them” instead of because of societal inequality and sheer *bad fortune* without safety nets to catch people. It is very much worth doing the work to put it in.

#disabled#disability#disableism#chronic illness#chronic pain#chronic fatigue#neurodivergence#child poverty#poverty#class#classism#history#writing#game writing#game design#generational poverty

102 notes

·

View notes

Note

thoughts on adhd diagonsis and the rising numbers of it? heard a couple different theories, including a school therapist saying that he thinks children are just getting misdiagnosed because they’re cutting recess times, but interested in your thoughts! lol

yea i talked about this a bit here but i would add for clarity:

this kind of narrative of 'rising rates of' [any dsm diagnosis, in this case adhd] is kind of misleading on the surface because these numbers, and cultural and medical attitudes toward these labels, vary widely. matthew smith gives a very abridged introduction to varying attitudes toward adhd globally, and points out that countries that have 'embraced' the adhd diagnosis and its corresponding drug treatments tend to be countries where pharma companies have pushed to expand their market for these drugs, and have been able to succeed in partnering up with local and regional medical guilds and practitioners' professional interests. which is to say that any 'rise' in 'adhd' should be interpreted with an eye to material factors, meaning, specifically, profit-seeking and broader patterns of imperialism and global market expansion.

none of this is to say that the impairments people experience in adhd are any less real, debilitating, or distressing. however, when we ask about those impairments becoming more widespread or severe, often the conversation becomes rapidly re-routed to cover only a narrative of individual cognitive or neurological 'failures' constituting a distinct 'disorder'. elided from this framing is the idea that an impairment of this sort arises not just from the individual's brain-mind-body, but from the extent to which that person is being accommodated by their social context, specifically demands for productivity, sustained attention, &c in the home / school / workplace.

the core research methodologies & data interpretation in the psy-sciences embed social valences into neuro-psychological investigations, heightening the perceived contrast between, eg, 'normal' and 'adhd' brains / neurotypes / &c. susan hawthorne points out that this is a powerful feedback loop: social values are embedded in the scientific investigations, the results of which are then of further social interest, and together social and scientific values tend to converge, mutually reinforce one another, and strengthen the ideas and data interpretations supporting the concept of a discrete, pharmacologically actionable, transhistorical and cross-societal brain disorder.

i truly cannot overstate the extent to which it matters that when ritalin arrived on the us market in 1955, psychiatric diagnosis of and pharmacological prescription for children's behaviours were in a very different state to how they are today. it is quite common (in psychiatry but also in other branches of medicine!) that diagnostic definitions and categories change, or even come into existence altogether, at the behest of pharmaceutical companies who need a diagnostic label in order to ensure insurance coverage for patients interested in taking their patented drugs. this combined with marketing direct to patients, and paid promotion to physicians, is a critical piece of the history of the adhd diagnosis.

because i always feel the need to make this crystal-clear: i do not oppose or object to people seeking or using stimulant medications lol. i <3 stimulants. that's not what this is about. i want you and me both to be able to use white-market amphetamines whenever we damn well please and you don't need to justify that on any moral or medical grounds. xx

134 notes

·

View notes

Note

All mental illness has the potential to be disabling and I think your other anon doesn't grasp that just because something isn't disabling for them doesn't mean that it isn't for someone else. I think in terms of these polls it shouldn't be looked at as "oh well for ME this doesn't disable me therefore it's not a mental illness that's a disability", it should be looked at as "does this mental illness this character has put them at a disadvantage in some way?" because at the end of the day disability is when something you have impairs your ability to function to societal norms. Which I could get into how BS societal norms are too but I'm trying to stay on the topic specifically of polls here.

Because we can argue all the live long day about what is or isn't a disability but at the end of said day it really does come down to the fact that a lot of chronic mental and physical conditions can and do often present differently and in one person maybe it's not so severe and they can function, but in another it's disabling and they haven't left the house in three days because the idea of having to talk to other people makes them have a panic attack. Or sometimes the severity can even change with or without intervention.

Thanks for the input

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notes on the Radical Model of Disability

I'm seeing a lot of discussion today about different models of disability, and wanted to share my recent reading notes on the radical model of disability, which for me has been a super helpful model for understanding how disability works.

"The radical model defines disability as a social construction used as an oppressive tool to penalize and stigmatize those of us who deviate from the (arbitrary) norm. Disabled people are not problems; we are diverse and offer important understandings of the world that should be celebrated rather than marginalized."

Source: AJ Withers, Disability Politics and Theory. "Looking Back But Moving Forward: The Radical Model of Disability"

Key Points:

The radical disability model was developed by many disability justice activists (including Sins Invalid and the 10 principles of Disability Justice), and was inspired by many different models, including the social model. Withers points out that there are a lot of valuable parts of the social model, but also lots of limitations.

The radical disability model is not the same thing as the social model of disability. It rejects the strict social model separation between "impairment" and "disability." Traditionally, in the strictest versions of the social model, people use "impairment" to describe someone's individual limitations--generally considered the "biological" part of disability. People often use things like chronic pain and hallucinations as examples of "impairment." In the strict social model, disability is described as oppression added on top of the "impairments" people are living with. People usually describe things like inaccessible buildings and strict social norms as examples of the disabling impact of society. Withers points out how sometimes, the social models ideas about the separation of impairment and disability can leave many disabled people feeling excluded and like their experiences aren't represented. This article by Lydia X. Z. Brown talks a little bit more about those topics--using the terms "essentialism" to describe the impairment view and "constructivism" to describe the social view.

Instead, the radical disability model argues that you cannot easily separate impairment and disability, and points out that both "impairment" and disability are always socially contextual. Disability must be analyzed in context to the society we are currently in, both so that we can understand the experience of oppression and so that we can understand the impact it has on our bodies and minds. For example, someone living with chronic pain will still have chronic pain no matter what society they live in. But things like whether they can sit while they work, whether they have to work at all, if they can afford assistive technology, if there is easy access to pain medications, etc, all affect their body and lived experience of pain in a very real way. Ending capitalism would not suddenly take away all the pain they are experiencing, or make them not disabled. But it might change their ability to cope with pain, what treatments are available to them, and what their bodily experience of pain is like. Similarly, someone's experience with hallucinations can be dramatically shaped by the context they are in, whether they are incarcerated, if their community reacts with fear, whether they have stable housing, and more. The radical model of disability looks at how the different contexts we live in can affect our very real experiences of disability. Instead of the medical model, that only looks at disability as a biological, individual problem that can only be fixed through medicine, or the strict social model, which focuses on changing society as the only solution for disability, the radical disability model looks at how different societal contexts change both our biological and social experiences. It acknowledges that disability is a very real experience in our bodies and minds, but looks at how the social environments we live in shape all parts of "impairment" and disability.

Intersectionality is a key concept for the radical disability model. Withers points out how disability studies often ignores intersectionality and only focuses on disability. "Disability politics often re-establish whiteness, maleness, straightness and

richness as the centre when challenging the marginality of disability. Similarly, when disability studies writers discuss other oppressions, they often do so as distinct phenomena in which different marginalities are compared (Vernon, 1996b; Bell, 2010). When oppressions are discussed in an intersectional road it is commonly treated like a country road: two, and only two, separate paths meet at a well-signed, easy-to-understand location. Intersectionality is a multi-lane highway with numerous roads meeting, crossing and merging in chaotic and complicated ways. There are all different kinds of roads involved: paved and gravel roads, roads with shoulders and those without and roads with low speed limits, high speed limits and even no speed limits. There is no map. The most important feature of these intersections, though, is that they look very depending on your location." (Withers pg 100.)

The radical model of disability is inherently political. The radical model of disability looks at who gets labeled as disabled, how definitions of disability change, and how oppressors set up systems that punish disabled citizens. Oppressors set up systems of control, violence, and incarceration that target disabled people, and shift the definitions of disability based on social and economic changes. Withers shares examples of this, talking about the eugenics movement in the United States as an explicitly white supremacist movement that defined "disability" in a way that targeted racialized people, how homosexuality was added and then taken out of the DSM, and many other examples of the way certain people are labeled as "deviant" and impacted by ableism. Disability becomes weaponized by oppressors as a tool of marginalization, and affects many different marginalized groups. This interview of Talila A. Lewis is a really great article that explains more about a broader definition of ableism, and expands on a lot of the topics mentioned here.

Disabled is not a fixed, one-size-fits-all, never changing identity. However, it is an important personal and political identity for many people, because our experiences of disability are real and impact our bodies, minds, and social experiences in many ways. Withers argues that in disabled community, we need to have room to celebrate and have pride in our disabled identity, as well as being able to recognize the pain, distress, and challenges that being disabled can cause us.

Within the radical model of disability, we should work collectively to build access and actively fight to tear down the systematic barriers that prevent a lot of disabled people from participating in our communities. Withers argues that we need to think beyond just changing architecture (although that's important too!) and understand the way things like colonialism and capitalism are also access barriers. Going back to the first point about disability in context, Withers explains that we must also think of access in context--there is no one "universal" way to make some accessible, and we need to be able to adapt our understanding of access based on the political and relational context we are in.

TL;DR: The radical model of disability is similar to the social model of disability, but instead of viewing disability as being only caused by society, it looks at how our real experiences of disability are always shaped by whatever social context we live in. It acknowledges that our disabilities are embodied experiences that wouldn't just suddenly go away if we fixed all of society's ableism. The radical model of disability is a political model that analyzes how definitions of disability shift based on how oppressors use systems of power to marginalize different groups of people. It offers us a framework where we can feel real pride in our disabilities, but still acknowledge the challenges they cause. It points out the importance of organizing politically to dismantle all kinds of access barriers, including things not traditionally thought of as access issues, like colonialism, capitalism, and other forms of oppression. Here's a link to another great summary by Nim Ralph.

other reading recommendations for understanding the radical disability model: “Radical Disability Politics Roundtable.” by Lydia X. Z. Brown, Loree Erickson, Rachel da Silva Gorman, Talila A. Lewis, Lateef McLeod, and Mia Mingus, edited by AJ Withers and Liat Ben-Moshe.

"Work in the Intersections: A Black Feminist Disability Framework.” by Moya Bailey and Izetta Autumn Mobley

"Introduction: Imagined Futures" from Feminist, Queer, Crip by Alison Kafer.

#personal#disability#actually disabled#disability justice#disability studies#chronic illness#radical model of disability#social model of disability#so grateful to all the disabled activists linked here!!!

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

So around a month ago the big NIH study on ME/CFS, in the works for eight years, was finally published and it was immediately met with hostility. I wrote about my initial reaction here and here. These were just some off the cuff remarks after my initial read through, I haven't had the energy to write on the problems with it at any depth, thankfully someone else has. This is a long one, but the criticisms are problems that have plagued research into ME/CFS for years: poor or no controls, loose diagnostic criteria, poor methodology and biased researchers. I want to focus on that last one with some excerpts, because it really is egregious.

As a rheumatologist, Walitt infiltrated and embedded himself into the world of ME (and now also Long COVID and Gulf War Illness) via Fibromyalgia. Although Walitt seemed to be doing a reasonable, though ultimately unconvincing, job feigning compassion toward his Fibromyalcgia patients, whom he paraded around in his presentations like circus attractions, his unhinged views are aggressively hostile toward ME and Fibromyaliga patients; he has been vocal with his conclusory view that both ME and Fibromyalgia are somatoform.

"The discordance between the severity of subjective experience and that of objective impairment is the hallmark of somatoform illnesses, such as fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome."

For well over a decade now, Walitt has been establishing himself as an ME and Fibromyalgia enemy who considers the symptoms of ME and Fibromyalgia as within the “range of normal” and not worthy of validation or treatment because, in his opinion, they do not constitute medical entities. What is abnormal, in his view, is the patients’ beliefs that they are suffering from a disease. As if it is not bad enough that an NIH researcher has been allowed to build a career on such propaganda, Walitt works hard to convert his colleagues whom he claims are relieved that they no longer have to pretend that Fibromyalgia is pathological after he “say[s] [his] message.” This disturbing ten-minute Walitt interview about Fibromyalgia will leave little to the imagination in terms of Walitt’s predisposition. I analyzed the ghastly views he expressed in this interview when independent advocates protested his involvement with the study.

Another good example of Walitt’s disturbed views on Fibromyalgia and ME is an opinion paper that he co-authored with his biopsychosocial soulmate, the late Dr. Frederick Wolfe: “Culture, science and the changing nature of fibromyalgia.” Somebody saved a copy of this paper on the Wayback Machine.

In this paper, in which he quotes Wessely and Shorter, Walitt equates Fibromyalgia with Neurasthenia—i.e., “the vapors,” “depression of spirit,” “hypochondriac affections,” “effort syndrome,” etc. Neurasthenia is a psychologized fatigue concept that had started out as a central-nervous-system disorder and was the predecessor of Holmes’s and Fukuda’s “CFS.” Walitt referred to Wessely’s framing of ME as Neurasthenia in the slick and insidious “Old wine in new bottles: neurasthenia and M.E.” In his paper, Walitt expresses his belief (no science required) that Fibromyalgia is psychocultural, i.e., “shaped primarily by psychological factors and societal influences” and is associated/comorbid with psychological illness. Throughout the paper, Walitt labels Fibromyalgia—in addition to psychocultural—psychological, psychogenic, psychosomatic, a Somatic Symptom Disorder (i.e., somatoform), a social construct, etc. He further claims that Fibromyalgia is related to psychological disorders (including major psychopathologies), psychosomatic symptoms, and personality disorders and that it is a convenient, because socially acceptable, diagnosis for mentally ill patients to hide behind. According to Walitt, Fibromyalgia patients are not to be trusted because they have too many symptoms that are too severe and too unusual while appearing too healthy resulting in physicians’ shunning of them. Walitt laments the failure of Fibromyalgia as a psychological concept and strongly disapproves of what he calls the “success” of Fibromyalgia. He sounds practically paranoid when he blames “powerful societal forces,” which he claims have been “marshalled,” for propping up the “‘real disease’ message.” Walitt frames Fibromyalgia as a con job by patients and patient organizations whom he claims were enabled by other malevolent actors and forces, such the American College of Rheumatology (guilty for naming and defining it), governments, disability and pension systems, physicians, the legal and academic communities, scientific organizations, pharmaceutical companies, the Internet, and ICD codes. That’s an impressive list. Imagine if patients indeed had the allyship of those stakeholders and systems! There is no other characterization of Walitt’s Fibromyalgia views than deranged. And, of course, because ME and Fibromyalgia are basically the same to him, all of this applies to ME according to Walitt’s twisted views.

As sordid as the government’s record regarding ME has been, the intramural NIH study has opened a new, even darker chapter for patients. Putting Walitt in charge of this study despite his unmistakable bias against ME patients is just one item on a long list evidencing an atrocious track record on the part of the federal health agencies, including NIH, when it comes to ME. It warrants a reminder that there have been calls by federal health officials to silence critical patient voices as well as actual threats against members of CFSAC—the since dissolved federal Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee—who refused to toe the party line in addition to many actions by federal officials designed to thwart patient advocacy.

Walitt’s unyielding belief that ME, Fibromyalgia, and other diseases are reflections of an incorrect inner understanding of patient body’s capabilities seems to have grown only stronger over the years. His extremism will likely be weaponized against patients for decades to come unless NIH stops involving him in these studies. So far, NIH has circled the wagons to defend him and even promoted him by moving him from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) to the more prestigious NINDS and making him head of the Interoceptive Disorders Unit.

When you put people like this in charge of your studies, it's because you wanted a certain predetermined outcome. Full stop. The rest of this is really quite good and covers a lot of ground, including the existential risk to ME patients' income this study poses and the implications for Long Covid sufferers.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women are being diagnosed with ADHD at unprecedented rates. Here's why. (Kaelyn Lynch, National Geographic, Jan 16 2024)

"There are three types of ADHD: hyperactive, inattentive, and combined.

Girls and women tend to have the inattentive type, characterized by disorganization, forgetfulness, and struggles with starting and staying on task.

“They’re more likely to be seen as daydreamers, or lost in the clouds,” says Julia Schechter, co-director of Duke University’s Center for Women and Girls with ADHD.

Even hyperactive or combined-type girls often display their symptoms differently than boys—such as excessive talking, twirling their hair or constantly shaking their legs, and emotional reactivity.

“Their symptoms are just as impairing, but can fly under the radar,” Schechter says.

When clinical psychologist Kathleen Nadeau co-authored Understanding Girls with ADHD in 1999—one of the first real attempts to characterize how ADHD appeared in young girls—the research community still thought of ADHD almost exclusively as a “boy disorder.”

“We were laughed at during conferences,” says Nadeau, now recognized as an authority on women with ADHD.

“They said, ‘We’ve got these guys that are in the principal’s office three times a week, getting suspended and throwing spitballs. And you’ve got these quiet girls making honor roll grades and you think they have ADHD?’”

While that attitude has started to change, the overwhelming majority of research on ADHD has been done in boys and men, leading to the hyperactive, disruptive boy stereotype of ADHD.

Many girls with ADHD excel in school, though it comes at a price—they may get an A on a paper but stay up the night before writing it after being unable to focus for weeks.

“Girls work very hard to hide their problems. ‘I don’t want the teacher to be mad at me, I don’t want my parents to be mad at me,’” Nadeau says.

Experts call this masking, or how people socialized as female tend to find ways to compensate for their symptoms due to societal expectations.

“They have to put in at least twice the effort of other people if they’re determined to do well,” Nadeau says.

“You can’t let people know that you’re falling apart,” says Janna Moen, 31, a postdoctoral research scientist at Yale Center for Infection and Immunity with a PhD in neuroscience, who was diagnosed with ADHD in her late 20s.

Like many girls who go untreated, Moen scored top grades in school and went on to have a successful career, but years of masking her symptoms contributed to her developing mental health and self-esteem issues, and struggling in personal relationships.

Like Moen, who showed symptoms of ADHD from childhood, girls and women are more likely to have their symptoms mistaken for emotional or learning difficulties and are less likely to be referred for assessments.

Gender bias also may play a role: in two studies where teachers were presented with vignettes of children with ADHD, when the child’s names and pronouns were changed from female to male, they were more likely to be recommended for treatment and offered extra support.

All these misconceptions mean that girls with ADHD are being overlooked and untreated well into adulthood.

As David Goodman, the director of the Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Center of Maryland and an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, points out, the ratio of boys to girls with ADHD in childhood is about three to one, while in adults, it’s about one to one, suggesting that ADHD prevalence is more equal across genders, with women being diagnosed later. (…)

Compared to their neurotypical peers, women with ADHD are more likely to suffer from anxiety and depression, substance abuse, and eating disorders.

They are also five times more likely to experience intimate partner violence, seven times more likely to have attempted suicide, and have higher rates of unplanned or early pregnancy.

One Danish study showed that the risk of premature death in women with ADHD was more than twice that of men with ADHD, potentially due to women being less likely to be diagnosed and receive treatment."

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Do My Autism, PDs, and DID Interact/Intertwine?

Disorders mentioned in this post: autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), tourette syndrome (TS), fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), dissociative identity disorder (DID), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), narcissistic personality disorder (NPD), and schizotypal personality disorder (STPD)

(This post was requested by a mutual, I hope you find this (somewhat) helpful and I apologize for taking a million years to post it 🙃)

I have a whole host of disorders, pretty much all of which affect my personality, identity, and way I interact with the world around me. A lot of people look at the combinations of disorders I have and tell me I can't possibly have them (this is especially popular with autism and ASPD, as well as autism and STPD), when I do in fact have them and they suck ass.

To begin with, since I have DID, my other disorders vary drastically in symptoms from alter to alter. It is important to note that individuals with DID will likely only be diagnosed with other disorders alongside DID if most or all of the frequently fronting alters show symptoms and those symptoms impair the whole. Disorders like autism, Tourette, ADHD, and FASD are system-wide disorders due to the nature of their development. Personality disorders are usually diagnosed at the discretion of the therapist or psychiatrist who is doing the diagnosis.

My combination of autism, NPD, and ASPD resulted in an individual who lacks essentially all empathy, is very isolated, and is really sensitive to perceived slights or criticisms.

I have the psychopathic subtype of ASPD, which means that even if I didn't have NPD I would have narcissistic traits. Alongside heightened NPD traits, I am also more prone to violence and aggression (it is important to note that most psychopaths and individuals with ASPD are not criminals or extremely aggressive). Features of psychopathy that I display are typical antisocial behaviors (disregard for societal norms and rules, essentially), increased aggression and violence, lack of empathy and remorse/guilt, and manipulative and deceitful behaviors.

When it comes to autism and ASPD, the only real trait my presentation has in common is a lack of empathy. Communication problems can arise for individuals who have both disorders, but for different reasons (my ASPD communication problems are almost exclusively related to my disregard for others and lack of remorse; while my autistic communication problems stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of social norms, sarcasm, facial expressions, gestures, and figurative language). Individuals who have ASPD will not experience any developmental delays like autism (delayed speech, social ineptitude, etc.).

My ASPD and NPD go hand-in-hand pretty well. The earliest memory I have of exhibiting antisocial behaviors is at age 8 when I would repeatedly steal candy from my friend's school locker because I felt I deserved it more than her; the theft just escalated from there. I was very good at getting people angry with me so I could take out my anger on them.

I don't feel that my autism and NPD really have that much in common, honestly.

If you would like to learn more about ASPD, its history, and the psychopathic subtype of ASPD, please visit this site: https://psychopathyis.org/what-is-a-psychopath/

#hope this is helpful people in my screen#also feel free to request elaboration#npd#aspd#autism#comorbidity#did#mmanifold rambles

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Conversation About Demedicalization and Disorders

Let's talk about demedicalization. What is demedicalization? The Open Education Sociology Dictionary defines demedicalization as "The process by which a behavior or condition, once labeled 'sick', becomes defined as natural or normal." It is the process of normalizing a trait of the body or brain or behavior as a normal variance of human existence, rather than a pathological variance in need of treatment or correction.

Put simply, it is no longer looking at something as a sickness in need of treatment, but rather just another way of existing.

Some background info that is needed: the social and medical models of disability.

The medical model posits that the existence of disability is predicated on inherent pathological differences in the bodymind, that it is active physical limitations, some of which can be treated or "corrected", that make a person disabled.

The social model, on the other hand, states that is is a societal lack of access and accommodations that disables a person, and that a person would no longer be functionally disabled were these access barriers to be removed. Keep in mind that this does not mean they believe that people would not still have "impairments" that affect how they are able to function, but that it defines disability as the disadvantages caused by an ableist society treating impairments as needing to be "fixed" rather than accommodated. I defines being abled as being able to participate in society to the full extent an impaired individual wishes to.

I believe in a mixed social-medical model. I believe that some conditions are inherently disabling and that seeking medical treatment for them, while it should be up to disabled individuals, is helpful and good. My ADHD, for example, will still limit my participation in society to the extent I want to, without medication. You could consider medication an accommodation, but there's also the example of my chronic pain and fatigue and POTS that often keeps me housebound or bedbound. There may not be a treatment for that, and I cannot fully participate in the world around me because of that.

"Ultimately, the social model of disability proposes that a disability is only disabling when it prevents someone from doing what they want or need to do."

I am actively prevented from doing what I want or need to do by an inherent feature of my body that no amount of accommodation can allow for. However, some of my conditions would not be disabling with proper accommodation - my autism, for example, I don't generally consider disabling because the people and structures around me DO accommodate for it.

So why is demedicalization helpful or necessary, and how is is applied?

Well, three psychological examples: autism, psychosis, and schizophrenia.

Autism is currently, in the DSM, called autism spectrum disorder. However, autism is a neurotype, and many autistic people do not feel that autism inherently causes them distress or dysfunction, and is therefore not disordered. That is why many of us call ourselves autistic people or say we have autism, rather than ASD. There has been a push for years for the diagnosis itself to be changed to not contain the word "disorder", and to allow for informed self-diagnosis.

Informed self-diagnosis is also an important part of demedicalization, especially of neurodivergence. It says "someone doesn't need a doctorate to know themselves and their own experiences well enough to categorize and classify them. Good research and introspection is enough to trust a person to make the call, and labeling oneself as a specific kind of neurodivergence is harmless, even if they later find out they were wrong.

Psychosis is the next example. There is a growing movement that I've talked about before: the pro-delusion movement. Not everybody experiences distressing delusions, and even when they are distressing, this movement says that only the individual experiencing them has the right to decide whether they should be encouraged or discouraged. It states that it is a violation of autonomy to nonconsensually reality check (tell someone their delusions are not reality) someone, and that as long as a person is not harming others, they can do as they like with their delusions.

This is an example of demedicalization. Treating delusions as something not to be suppressed with medication or ignored or "treated" or "fixed", but as simply another, morally and "healthily neutral" way of existing outside homogenous neurotypical norms.

Finally plurality. Now what's key here is that demedicalization does not mean saying a thing can NEVER be disordered. In fact, that's why I made this post. I saw someone the other day say that they felt their aromantic identity was disordered. Initially, I balked, thinking they were internally arophobic, but I listened to what they had to say. Essentially, they expressed that the identity was never inherently disordered, but that it caused them distress and dysfunction and so they experienced it as such, and crucially, that wasn't a morally bad thing or something they felt they had to correct.

Because here's I think what gets left out of discussions on demedicalization: demedicalization also means no longer treating disorders as something that inherently have to be treated or fixed, that disorders can simply exist as they are if the person with a disorder so chooses; and that anything can be labeled a disorder if it causes distress and dysfunction without being inherently disordered AND without needing to be treated.

And conversely, this means that if you experience something as disordered, demedicalizing it means that you do not have to meet an arbitrary categorical set of requirements to seek treatment, but can do so based on self-reported symptoms. Treatment cannot be gatekept behind a diagnosis that only a "qualified professional" can assign you.

This means if someone wants to, they can label their autism as disordered, but it is never forced on anyone. If someone feels ANY identity - neurodivergent, disabled, queer, alterhuman, paraphilia, whatever - is disordered, they can label it as such, but they also don't have to. There are no requirements to follow through with "treating" anything you label a disorde, either. No strings attached, just the right to self-determination and the right to autonomy hand in hand,

So, back to plurality. You essentially end up with three aspects of demedicalization. You have nondisordered plurality being normalized, you have dissociative disorders that systems can choose not to pursue treatment for without judgment or coercion, and you have disordered systems that can pursue treatment for dissociative symptoms without receiving a difficult-to-access diagnosis. Based on their experiences, they can choose to label themselves as having DID, OSDD, UDD, or related disorders, or to forgo the label and simply seek treatment for whatever distress or dysfunction the disorder is causing.

"But without a specific diagnosis, what if they pursue the wrong treatment and it harms them?"

This is where the importance of recognizing self-reported symptoms as valid comes in. If an OSDD-1b system that hasn't labeled themselves or receives a diagnosis reports that they don't experience amnesia, they won't receive treatment for amnesia.

And since symptoms can mask, if a DID system reports not experiencing amnesia, they simply do not become aware of it or receive treatment for it before they are ready, which is a good thing because recognizing certain symptoms before you are ready to deal with them can be destabilizing and dangerous. More awareness of dissociative disorders will also make it easier for systems to adequately recognize those symptoms, and this isn't saying that someone else can't suggest it to the system experiencing it. It's simply saying the person experiencing a disorder takes the lead and is centered as the most important perspective.

I consider myself to have several disorders and several forms of nondisordered neurodivergence. My BPD is disordered but I am not treating it because I have healthy coping skills already. Same with my schizophrenia. My narcissism, on the other hand, is simply a neurotype. My plurality is both - the plurality itself isn't disordered, but I do have DID on top of it.

A last example, this one physical, of demedicalization: intersex variations. The intersex community has been pushing to recognize that intersex variations are natural variations in human sex, and not medical conditions that need corrected. This doesn't mean that any unpleasant symptoms related to an intersex variation can't ever be treated - in fact, it's important to the community to have that bodily autonomy to access whatever reproductive healthcare is needed - but it does mean treating our sexes as inherently normal and NOT trying to coercively "correct" them.

So in summary, demedicalization is fundamentally about autonomy. It is about considering natural human variations as such, rather than as sickness to be cured, about letting people determine for themselves whether any aspect of themselves is disordered, and the decision on whether or not to pursue treatment for anything being theirs alone. It is about trusting people to be reliable witnesses and narrators of their own subjective internal experiences, and about never forcing anyone to change any aspects of themselves, disordered or not, that aren't harming others. In short, it is about putting power back into the hands of disabled people. And that is what this blog is all about.

#unitypunk#long post#demedicalization#autonomy#social model of disability#medical model#disorders#intersex#self diagnosis

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

One famous skeleton, found in Shanidar cave in Iraq, illustrates particularly well the extent to which evidence for caring behaviours has changed our assumptions about the character of our ancestors. This particular skeleton, Shanidar 1, or ‘Ned’, has been the subject of much debate about the emotional dispositions of Neanderthals (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) and the extent to which they were kind or callous.

Ned had certainly had a very rough life. He lived around 45,000–70,000 years ago and survived a remarkable level of injury and impairment. His bones were excavated between 1957 and 1961, and demonstrated many different injuries. Probably, as a young adult, he had suffered a blow to the left side of his face, resulting in blindness or only partial sight in one eye. He also had a hearing impairment; a withered right arm, the lower part of which had been lost after a fracture, and possible paralysis; deformities in his foot and leg, leading to a painful limp; and advanced degenerative joint disease. How he suffered his eye-watering range of injuries is not entirely clear, though there has been speculation that he may have been injured in a rock fall.

What was remarkable about this individual was not his injuries themselves but the length of time over which he had survived despite them. He had been injured at least 10 to 15 years before his death, with the curvature of his right leg compensating for injuries to the left. Yet Ned lived until he was aged between 35 and 50, relatively old for a Neanderthal, despite his range of debilitating impairments. These restricted mobility, ability to perform manual tasks, and perception. Solecki (1971), and later Trinkaus and Shipman (1993), argued that he could not have survived without daily provision of food and assistance. Trinkaus and Zimmerman even commented (1982: 75) that Neanderthals ‘had achieved a level of societal development in which disabled individuals were well cared for by other members of the social group’. Aside from Ned himself, there are many other cases suggesting care against the odds. We now have a wealth of evidence for Neanderthal care, with more than 20 cases of probable care for illness or injury recorded. In many, it is clear from the severity of illness or injury and evident lack of possibility of recovery that only genuine caring motivations rather than any calculated reasons explain the help the injured received.

After his treatment in life, Ned was also carefully buried after death.

Penny Spikins, Hidden Depths: The Origins of Human Connection

271 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone else with a chronic illness, physical or neurological disability use Undertale (or another fandom) and possibly it’s AUs to cope with and explore your feelings in a safe setting?

Characters like Wine, Black and Razz are powerful and in control. Their bodies facilitate abilities that are commanding and seemingly without limits. In complete comparison to how many physically disabled see and experience their bodies.

Horrortale Sans and Papyrus commonly experience brain / memory impairment and chronic pain respectively. We can explore attitudes in a safer place where the people around them are kind. We can place our struggles into them and view them in a place that’s separate to our own bodies, which then doesn’t constantly remind us of our own selves.

Characters like Blue, Stretch, Cash/Money and Mutt allow us to experience relationships most of us will never have. They would always tell us ‘no, it’s not your fault’, and ‘you do have worth’, always encouraging and validating us.

Our OCs and paras can reflect any number of experiences, thoughts and challenges due to the diverse nature of the series. My para who we will call V is a human/monster hybrid created in a lab, which explores themes like medical negligence, societal attitudes and stigmas as she doesn’t fit into either human or monster bracket fully. In one of the AUs she has sight and neurological-adjacent disabilities which create symptoms similar to some of my own, but I get to experience them through the lens of someone who has a strong support framework behind her now.

I’d love to know if I’m not alone in this and hear from others because my Undertale paracosm and the fandom has done so much for me, helping me through the last 3 or so years of my incurable, untreatable and unsupported mess of a disability. In a world that hurts us, we’ve created a shared world which is there for all of us, and I think that’s absolutely beautiful.

#undertale#undertale au#sans#papyrus#sans undertale#underfell#underswap#horrortale#disability#chronic illness#undertale fandom#disabilities#dps thinks

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

(personal journal thoughts time!!)

was not always this visibly autistic, was not always unable to mask, was not always mostly nonspeaking. but when younger, even though less disabled than now, have at least been semispeaking, at least mid support needs, at least low end of level 2, even though able to speak and relied on speaking primarily, even though able to mask more, even though more functional.

but even with me being better off younger than now, it wild to hear how different even my "better off younger days" are from other late diagnosed, AFAB, speaking, high masking autistics who... i really don't want to assume their support needs or levels, but don't know better ways to say it so am going to make assumption blanket statement... who most likely are lower support needs and level 1.

it's like. i always thought i was not that disabled when younger, not that stereotypically visibly autistic when younger. but then find out while that's still half true, even my "better days" were more visibly autistic more "impaired" (for lack of better term) than i thought i was.

for example, this tiktok. absolutely no hate to the creator or the person who stitched this, not criticizing what they say (have problem with how they generalize their experience to all "autistic girls" as if all have ability to mask but that is not focus of this) just comparing self to them: https://www.tiktok.com/t/ZTRQcsFaR/

the OP talk about experiences as a high masking AFAB person forced to mask to perform femininity. it wild for me to realize that even in younger "better" child years (like elementary middle school and even high school) when i more aware of social things than am now, i didn't do any of the masking behaviors they said they do. even among my "most aware of social things" years i wasn't aware that i as a perceived feminine person was supposed to or expected to do that. i literally wasn't aware.

to think that even when i was "better off" when i was less disabled/less visibly autistic than now, i was still more socially impaired than the common/dominant online autistic community experience.

sorry i repetitive

"the make up the hair the clothes the body posture," all that the OP say that they mask due to expectation as an AFAB person. i never did any of that, i never thought to do any of that, i never changed any of that or known to change any of that. i didn't care about appearance, i didn't think to, i literally didn't perceive this aspect of societal expectations, i didn't know that everyone else was dressing the way they do not because they want to but because they feel pressured to.

"thinking about where the lights come into the room so it can hit my face in a certain way so i can be the most attractive" WHAT?? i was shocked to hear that concrete example because never once in my life have i thought about this.

"pretending to be stupid" "only liking certain things and not other things" i didn't even know to do that!! it make sense now that i hear about it, it make sense why they feel pressured to do that, but i never thought to do that.

"putting on clothes that were uncomfortable" "trying to get boys attention" "hyper fixating on hair and clothes and makeup and magazines and boys" never never did that for others. never thought to?? sometimes i used to wear uncomfortable clothes but only because i like them and i want to wear them for self. never thought to dress for other people.

(and not saying that i am superior for not doing any of these or OP is shallow for doing any of these!)

it's just wild to think about! realizing that your "best" is more "impaired" (again for lack of better term) than the community's average.

#actually autistic#actuallyautistic#high support needs#level 2 autism#level 2/3 autism#🍞.txt#long post

150 notes

·

View notes

Note

probably a silly question, but i was under the impression that mental shutdowns can either kill or put someone in a coma, while psychotic breaks make the victim abandon all societal norms and whatever inhibitions they had. sort of like. it will make them act like their worst self and desires and intrusive thoughts but it won't kill them. is this wrong? :0 i guess even in my interpretation a psychotic break can make someone act in such a way that will cause them serious body harm or death. but can a psychotic break kill on its own?

You have it right, anon! Definitions again:

psychotic breakdown—more literally something like "mental rampage", this is the result of Akechi using Call of Chaos on someone's shadow. The game implies (with statements like "once the chains on [their] heart are broken") that the things people do during a breakdown are things they can't admit they want to do; the things they repress down into their shadow. These result in "accidents and scandals", and (probably?) won't kill you directly.

mental shutdown—the result of Akechi killing someone's shadow, this is haijinka, more literally "cripple-ization" or "making someone a human wreck" (thanks so much, y'all)—note that 廃人 haijin is derogatory and "should be used with caution".

Here's Japanese Wikipedia (via Google Translate bc I'm both lazy and busy this morning) on haijin:

When people are generally called "haijin", most of them refer to cases in which sociality is significantly impaired compared to healthy people . Because of the particularly strong discriminatory elements, it is used when the mind is destroyed or activity is hindered due to congenital (or acquired) mental disorders, or when normal social activities are difficult.

Note that, while these are two very different things, with very different effects, the localisation typically muddies the water by saying shutdown when it means breakdown, or vice versa. Or by turning "shutdowns and breakdowns" into one or the other. Or by describing something else entirely as a mental shutdown—the cases in that post are breakdowns, but they're a specific subset of breakdown. So when you hear these mentioned in English, think about what they're describing, and which definition it meets. The characters are often validly confused about what's going on, but the terminology is also usually muddled, one way or another.

how fatal are they tho

Using @cincosechzehn's original spreadsheet as an indicator, we see five mental shutdowns in canon, as part of the plot: Wakaba, Kayo, Kobayakawa, Okumura and the SIU Director. Out of these five, the only five we see onscreen, four of them die and one recovers.

Those are bad odds. Those are really bad odds. That's an 80% kill rate. Like, the SIU guy and Okumura may not be in good health, but by their nature mental shutdowns are going to tend to target older people in power. Wakaba and Kobayakawa may just in the wrong place at the wrong time—but that's still 40%; going brain dead in the real world is not safe.

On the upside, the only person we hear about having a mental shutdown and not dying immediately does begin to recover in the medium term. But Sae (a reliable source, unlike the TV news) tells us people "lose consciousness, never to recover"—which likely makes those odds a bit worse.

Based on this, I would be really hesitant about saying "mental shutdowns aren't fatal". 80% fatal is essentially "only not murder because I missed". Additionally, it looks like Shido and the SIU Director may sometimes send the Cleaner in to "clean up", when a shutdown victim doesn't die first time—for instance, he may have been responsible for that truck that hit Kobayakawa. Not sure about this one yet.

what about the psychotic breakdowns?

Again, a psychotic breakdown seems to make you rampage and do something you secretly want to do, but are usually restrained from by little things like morality and not hurting others. They often seem so targetted (Akechi gives X a psychotic breakdown to make them do useful thing Y) that I think there must be an interrogation element—like he talks to the shadow to see what it wants to do, and maybe has to take time to find one that will serve his purpose. For instance, if he wants a flashy subway accident, he can't CoC a random train driver who it turns out just wants to slam on the brakes and jerk off.

So the breakdowns are described as "accidents and scandals", because sometimes they're devastating, but sometimes someone just loses their mind and does something weird. Or they start swinging a knife around on a train.

And here we need to get into intent. Akechi doesn't have a death note, after all. He can't just write down "this guy smashes his train through several stations at top speed, eventually derails it with catastrophic effect, and nobody dies." He sends the driver in knowing the likelihood is that the result will be a lot of dead people.

Because that's what happens. Akechi starts the ball rolling, probably with a rough idea that it will serve the purpose he was assigned, and then he has to let it roll and see where it lands.

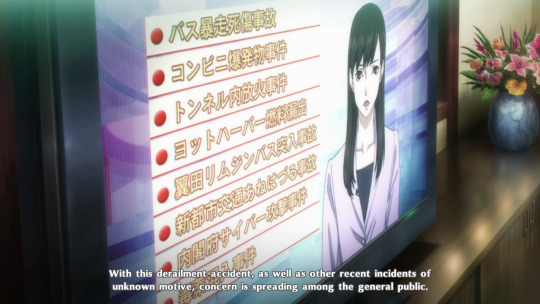

This is why almost the first thing that happens in the game is that we get told about a "rampage accident" that is fatal:

(I figured this list really deserved its own post.)

Here's the top item on that list again:

バス暴走死傷事故

basu bousou shishou jiko

reckless bus driving accident that caused injuries and deaths

This is a really interesting choice for the top item in the list. It's a case of 暴走運転 bousou unten "reckless driving", sure. But Japanese players are going to get very used to that word bousou, very quickly, in the context of the 精神暴走事件 seishin bousou jiken—the psychotic breakdown cases.

This is an explicit link between the word bousou—Akechi's word that describes his unique signature skill and his effect on others and ultimately his combat style—and a fatal accident. And it's right up at the front of the game, when about all we know about "psychotic breakdowns" is that some girls were talking about them as a spooky occult thing, on the train into Shibuya. Like, they could have chosen almost any of the things on this list to make fatal. But it was this one, and IMO that's important. The subway train derailing may not have been fatal, but the first thing the game wants us to know about psychotic breakdowns is that a. that people are terrified by them, b. that they can be extremely dramatic, and c. that people die from them.

To address your question again, specifically: no, people (probably; see below) don't die just from having a psychotic breakdown. But nobody "just" has a psychotic breakdown. The point is to make them do something—and the thing they do may well be devastating, and cause devastating injuries, up to and including deaths. Or it may just be personally devastating.

but then there are the chats and news stories

There are a lot of in-game rumours about psychotic breakdowns, and a lot of what appears to be misinformation, mainly because the difference between psychotic breakdowns and mental shutdowns is not clear.

One rumour is that breakdowns lead to mental shutdowns: "those people end up going brain dead", "they become haijin during interrogation". Another is that "you suddenly pass out ... [and] die in a lot of pain". Well, rumours are rumours.

But we also hear that "the news is saying the [train] driver couldn't even speak when they tried asking him questions". Of course, we know the news is controlled... but then we have to ask ourself what else they aren't reporting on.

doesn't akechi give himself psychotic breakdowns

The quick answer here is no. You could maybe argue that he does when the only example we had was the engine room, but in the third semester we get his Showtime, when he uses it repeatedly to put himself into a berserker rage. It looks like it gives him a bit of a headache afterwards, or makes him dizzy.

Call of Chaos just doesn't seem to work the same on Akechi (or, for that matter, on the two ordinary shadows he casts it on) as it does on people's shadows, when it goes "up the chain" and controls them in the real world. The immediate thing I'd point out is that Akechi doesn't drool blood (that I've noticed, at least) and his eyes don't roll back in his head (you can see his irises, albeit tiny and extremely crazy). Akechi can still speak, though he doesn't make much sense. He's not entirely out of control (despite being in, seemingly, a blind killing rage, he never attacks Joker in the Showtime—and there's a plot bunny for anyone who wants to pick it up and run with it.)

He is not experiencing exactly what his victims do—though he's experiencing something very similar: a lifting of his "chains", his inhibitions. It really seems like a true psychotic breakdown may be something that lingers with you, that lasts a long time, that probably leaves you in ruins. I'm not sure we ever hear of anyone who had one and was fine afterwards, though I can't swear to this.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like the social model of disability literally started primarily with physically disabled people, but the way a lot of people talk about it now warps it into excluding them. Neurodiversity was never supposed to mean "nobody is actually mentally disabled, just misunderstood by society, not like those people who are really disabled". It's like they took "it's all in your head" and shifted it to "it's all in our collective heads".

And especially with autism I think a lot of people misunderstood the idea of it being a social disability. That doesn't mean all the struggles are imposed from outside, from the social system. It's socially constructed sure, in the same way that all disabilities are. They are defined and understood in ways constructed by the culture and society they're in. But there's nothing intrinsically less real or disabling about the impairments in it than any other disability.

Like constantly now we get people saying that somehow we don't actually struggle to understand social situations, we don't have trouble understanding sarcasm or facial expressions or whatever, that's just neurotypicals misunderstanding us. That we just don't fit into capitalism and all our impairments are about work and we'd all be fine if we just lived on a fucking farm or something. And the semantics of whether "disability" should generally refer to the impairments or the societal barriers affecting people feels like so small and far away when you have to wade through all that crap first.

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

I like Chapter 394, I like that Ochako finally took a chance to try to talk and connect to Toga, I like that Ochako tried to empathize with Toga and to see her as someone worth— maybe not saving, exactly, but worth giving empathy and compassion to, even if she is a Villain, even if she has done terrible things. Someone worth allowing dignity.

I do feel like this realization is a bit… overdue. Ochako acknowledges this herself - it might have been too late for a talk. The signs where there from the beginning, but it took her so long to notice. She had avoid really considering Toga Himiko until the last possible second.

This realization as a climax in a narrative does work, technically. You had:

the problem (What’s the deal with Toga Himiko and how do we stop her),

the rising action (Making a plan to confront Toga Himiko, fighting through to clones to reach Toga Himiko, trying to figure out Toga Himiko),

and so the climax is the solution - We stopped Toga Himiko by talking to her, realizing she’s been afraid that she’s not cute she’s considered not human, and so reassured her that she’s human.

But the way all this has been executed feels… off.

Because there’s very little about the villains that we the audience don’t already know, but there’s a lot about the villains that the Heroes haven’t even got a clue of. The audience have known the basic facts; and then we were just waiting for the Heroes to play catch up, to learn what we learned and to realize what we’ve realized nearly 200 chapters ago. Waiting for the Heroes to gain that knowledge, then use it to win the battle.

As it is, Ochako has finally realized that Toga has a strange instinct for blood that impairs her life and relationships, that Toga has not had an easy life because of it, that Toga wanted and needed human connection. All that is great, it’s exactly what was needed to de-escalate the situation and stop Toga at the moment.

And yet something feels lacking. Ochako still has no knowledge of how Toga’s parents treated her, or how quirk counseling did more harm than good, or even exactly why and how much Jin meant to Toga. She understand a bit of Toga’s problem now, and? How will she solve the rest of the problem?

In a way, I guess this is realistic. You don’t need to know everything about a person to help them. You can’t know everything about a person, and you make do with what you have. And a Hero should be willing to help someone even with limited information.

For a story, though, about flawed systems, and the societal accumulation of pain and injustice, and human connections, it’s rather unsatisfactory. What is Ochako, as a Hero who participates in the system and perpetuates it’s justice, willing to do about the root causes that created Toga Himiko? Will she get angry about the abusive parents and the quirk counseling and the overall intolerance of quirk society, these injustices that she as a Hero should stop? How will she truly stop the threat of ‘Toga Himiko’ - the threat of another ostracized, abused child pushed to the edge and lashing out as a result? Is she even aware of how big this is?

Ochako’s realization here is important! It’s the first step. But it’s a tiny part of a bigger epiphany to be had. It feels like she hasn’t reached the true climax.

36 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is Feedism a mental illness? Whenever I look up feeder stuff on youtube, that's mostly what I see people saying about this fetish

According to the official psychological definition of mental disorders, the answer is No.

There's a lot of jargon here, but to summarize, psychologists only call it an illness ("disorder" is the preferable word these days) when fetishes cause "personal distress or impairment". Essentially, is the fetish disordering your life and causing you unhappiness? Or is it putting other non-consenting people in distress? Then it's a disorder. Are you happy and fulfilled while engaging in consensual, but non-typical sexual practices? Then it's just a preference. One that you're probably being judged for having, by the way.

People love to stigmatize those that don't conform to current societal norms. Remember, up until a few years ago, being gay, trans, or non-binary was considered a mental illness. The same hatred is being unfairly applied to feedism.

There's nothing wrong with having a feedism fetish. You are not mentally ill for what you like. And don't let judgmental critics tell you otherwise.

26 notes

·

View notes