#roger ackroyd

Text

the murder of roger ackroyd spoilers under the cut

doodles of my doc sheppard design from when i first read the book. i legit haven’t drawn him since then so it’s making me very happy to look at the improvement :]

(ft. bonus video that i made 3 years ago cause i still think it’s kinda funny lmao ⬇️)

#the murder of roger ackroyd#doctor james sheppard#roger ackroyd#hercule poirot#agatha christie#i have a thing for the medical people in these books i think#i was reading 12bms recently and istg when poirot described the killer (spoilers) like becoming a dentist#i was like OH MY GOOOODD🥶…. oh my gooood……🥵#i might draw him at some point too i have a design in mind#i am currently working on an mv for the 48< murders tho so#you can look forward to me butchering THOSE guys too!!! ✌️✌️✌️

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

today i made two loaves of bread, finished an agatha christie novel, and repaired my singer manual sewing machine. im in my great depression era

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Agatha Christie

Chapter 5-6

CHAPTER V

MURDER

I got out the car in next to no time, and drove rapidly to Fernly. Jumping out, I pulled the bell impatiently. There was some delay in answering, and I rang again.

Then I heard the rattle of the chain and Parker, his impassivity of countenance quite unmoved, stood in the open doorway.

I pushed past him into the hall.

“Where is he?” I demanded sharply.

“I beg your pardon, sir?”

“Your master. Mr. Ackroyd. Don’t stand there staring at me, man. Have you notified the police?”

“The police, sir? Did you say the police?” Parker stared at me as though I were a ghost.

“What’s the matter with you, Parker? If, as you say, your master has been murdered——”

A gasp broke from Parker.

“The master? Murdered? Impossible, sir!”

It was my turn to stare.

“Didn’t you telephone to me, not five minutes ago, and tell me that Mr. Ackroyd had been found murdered?”

“Me, sir? Oh! no indeed, sir. I wouldn’t dream of doing such a thing.”

“Do you mean to say it’s all a hoax? That there’s nothing the matter with Mr. Ackroyd?”

“Excuse me, sir, did the person telephoning use my name?”

“I’ll give you the exact words I heard. ‘Is that Dr. Sheppard? Parker, the butler at Fernly, speaking. Will you please come at once, sir. Mr. Ackroyd has been murdered.’”

Parker and I stared at each other blankly.

“A very wicked joke to play, sir,” he said at last, in a shocked tone. “Fancy saying a thing like that.”

“Where is Mr. Ackroyd?” I asked suddenly.

“Still in the study, I fancy, sir. The ladies have gone to bed, and Major Blunt and Mr. Raymond are in the billiard room.”

“I think I’ll just look in and see him for a minute,” I said. “I know he didn’t want to be disturbed again, but this odd practical joke has made me uneasy. I’d just like to satisfy myself that he’s all right.”

“Quite so, sir. It makes me feel quite uneasy myself. If you don’t object to my accompanying you as far as the door, sir——?”

“Not at all,” I said. “Come along.”

I passed through the door on the right, Parker on my heels, traversed the little lobby where a small flight of stairs led upstairs to Ackroyd’s bedroom, and tapped on the study door.

There was no answer. I turned the handle, but the door was locked.

“Allow me, sir,” said Parker.

Very nimbly, for a man of his build, he dropped on one knee and applied his eye to the keyhole.

“Key is in the lock all right, sir,” he said, rising. “On the inside. Mr. Ackroyd must have locked himself in and possibly just dropped off to sleep.”

I bent down and verified Parker’s statement.

“It seems all right,” I said, “but, all the same, Parker, I’m going to wake your master up. I shouldn’t be satisfied to go home without hearing from his own lips that he’s quite all right.”

So saying, I rattled the handle and called out, “Ackroyd, Ackroyd, just a minute.”

But still there was no answer. I glanced over my shoulder.

“I don’t want to alarm the household,” I said hesitatingly.

Parker went across and shut the door from the big hall through which we had come.

“I think that will be all right now, sir. The billiard room is at the other side of the house, and so are the kitchen quarters and the ladies’ bedrooms.”

I nodded comprehendingly. Then I banged once more frantically on the door, and stooping down, fairly bawled through the keyhole:—

“Ackroyd, Ackroyd! It’s Sheppard. Let me in.”

And still—silence. Not a sign of life from within the locked room. Parker and I glanced at each other.

“Look here, Parker,” I said, “I’m going to break this door in—or rather, we are. I’ll take the responsibility.”

“If you say so, sir,” said Parker, rather doubtfully.

“I do say so. I’m seriously alarmed about Mr. Ackroyd.”

I looked round the small lobby and picked up a heavy oak chair. Parker and I held it between us and advanced to the assault. Once, twice, and three times we hurled it against the lock. At the third blow it gave, and we staggered into the room.

Ackroyd was sitting as I had left him in the arm-chair before the fire. His head had fallen sideways, and clearly visible, just below the collar of his coat, was a shining piece of twisted metalwork.

Parker and I advanced till we stood over the recumbent figure. I heard the butler draw in his breath with a sharp hiss.

“Stabbed from be’ind,” he murmured. “’Orrible!”

He wiped his moist brow with his handkerchief, then stretched out a hand gingerly towards the hilt of the dagger.

“You mustn’t touch that,” I said sharply. “Go at once to the telephone and ring up the police station. Inform them of what has happened. Then tell Mr. Raymond and Major Blunt.”

“Very good, sir.”

Parker hurried away, still wiping his perspiring brow.

I did what little had to be done. I was careful not to disturb the position of the body, and not to handle the dagger at all. No object was to be attained by moving it. Ackroyd had clearly been dead some little time.

Then I heard young Raymond’s voice, horror-stricken and incredulous, outside.

“What do you say? Oh! impossible! Where’s the doctor?”

He appeared impetuously in the doorway, then stopped dead, his face very white. A hand put him aside, and Hector Blunt came past him into the room.

“My God!” said Raymond from behind him; “it’s true, then.”

Blunt came straight on till he reached the chair. He bent over the body, and I thought that, like Parker, he was going to lay hold of the dagger hilt. I drew him back with one hand.

“Nothing must be moved,” I explained. “The police must see him exactly as he is now.”

Blunt nodded in instant comprehension. His face was expressionless as ever, but I thought I detected signs of emotion beneath the stolid mask. Geoffrey Raymond had joined us now, and stood peering over Blunt’s shoulder at the body.

“This is terrible,” he said in a low voice.

He had regained his composure, but as he took off the pince-nez he habitually wore and polished them I observed that his hand was shaking.

“Robbery, I suppose,” he said. “How did the fellow get in? Through the window? Has anything been taken?”

He went towards the desk.

“You think it’s burglary?” I said slowly.

“What else could it be? There’s no question of suicide, I suppose?”

“No man could stab himself in such a way,” I said confidently. “It’s murder right enough. But with what motive?”

“Roger hadn’t an enemy in the world,” said Blunt quietly. “Must have been burglars. But what was the thief after? Nothing seems to be disarranged?”

He looked round the room. Raymond was still sorting the papers on the desk.

“There seems nothing missing, and none of the drawers show signs of having been tampered with,” the secretary observed at last. “It’s very mysterious.”

Blunt made a slight motion with his head.

“There are some letters on the floor here,” he said.

I looked down. Three or four letters still lay where Ackroyd had dropped them earlier in the evening.

But the blue envelope containing Mrs. Ferrars’s letter had disappeared. I half opened my mouth to speak, but at that moment the sound of a bell pealed through the house. There was a confused murmur of voices in the hall, and then Parker appeared with our local inspector and a police constable.

“Good evening, gentlemen,” said the inspector. “I’m terribly sorry for this! A good kind gentleman like Mr. Ackroyd. The butler says it is murder. No possibility of accident or suicide, doctor?”

“None whatever,” I said.

“Ah! A bad business.”

He came and stood over the body.

“Been moved at all?” he asked sharply.

“Beyond making certain that life was extinct—an easy matter—I have not disturbed the body in any way.”

“Ah! And everything points to the murderer having got clear away—for the moment, that is. Now then, let me hear all about it. Who found the body?”

I explained the circumstances carefully.

“A telephone message, you say? From the butler?”

“A message that I never sent,” declared Parker earnestly. “I’ve not been near the telephone the whole evening. The others can bear me out that I haven’t.”

“Very odd, that. Did it sound like Parker’s voice, doctor?”

“Well—I can’t say I noticed. I took it for granted, you see.”

“Naturally. Well, you got up here, broke in the door, and found poor Mr. Ackroyd like this. How long should you say he had been dead, doctor?”

“Half an hour at least—perhaps longer,” I said.

“The door was locked on the inside, you say? What about the window?”

“I myself closed and bolted it earlier in the evening at Mr. Ackroyd’s request.”

The inspector strode across to it and threw back the curtains.

“Well, it’s open now anyway,” he remarked.

True enough, the window was open, the lower sash being raised to its fullest extent.

The inspector produced a pocket torch and flashed it along the sill outside.

“This is the way he went all right,” he remarked, “and got in. See here.”

In the light of the powerful torch, several clearly defined footmarks could be seen. They seemed to be those of shoes with rubber studs in the soles. One particularly clear one pointed inwards, another, slightly overlapping it, pointed outwards.

“Plain as a pikestaff,” said the inspector. “Any valuables missing?”

Geoffrey Raymond shook his head.

“Not so that we can discover. Mr. Ackroyd never kept anything of particular value in this room.”

“H’m,” said the inspector. “Man found an open window. Climbed in, saw Mr. Ackroyd sitting there—maybe he’d fallen asleep. Man stabbed him from behind, then lost his nerve and made off. But he’s left his tracks pretty clearly. We ought to get hold of him without much difficulty. No suspicious strangers been hanging about anywhere?”

“Oh!” I said suddenly.

“What is it, doctor?”

“I met a man this evening—just as I was turning out of the gate. He asked me the way to Fernly Park.”

“What time would that be?”

“Just nine o’clock. I heard it chime the hour as I was turning out of the gate.”

“Can you describe him?”

I did so to the best of my ability.

The inspector turned to the butler.

“Any one answering that description come to the front door?”

“No, sir. No one has been to the house at all this evening.”

“What about the back?”

“I don’t think so, sir, but I’ll make inquiries.”

He moved towards the door, but the inspector held up a large hand.

“No, thanks. I’ll do my own inquiring. But first of all I want to fix the time a little more clearly. When was Mr. Ackroyd last seen alive?”

“Probably by me,” I said, “when I left at—let me see—about ten minutes to nine. He told me that he didn’t wish to be disturbed, and I repeated the order to Parker.”

“Just so, sir,” said Parker respectfully.

“Mr. Ackroyd was certainly alive at half-past nine,” put in Raymond, “for I heard his voice in here talking.”

“Who was he talking to?”

“That I don’t know. Of course, at the time I took it for granted that it was Dr. Sheppard who was with him. I wanted to ask him a question about some papers I was engaged upon, but when I heard the voices I remembered that he had said he wanted to talk to Dr. Sheppard without being disturbed, and I went away again. But now it seems that the doctor had already left?”

I nodded.

“I was at home by a quarter-past nine,” I said. “I didn’t go out again until I received the telephone call.”

“Who could have been with him at half-past nine?” queried the inspector. “It wasn’t you, Mr.—er——”

“Major Blunt,” I said.

“Major Hector Blunt?” asked the inspector, a respectful tone creeping into his voice.

Blunt merely jerked his head affirmatively.

“I think we’ve seen you down here before, sir,” said the inspector. “I didn’t recognize you for the moment, but you were staying with Mr. Ackroyd a year ago last May.”

“June,” corrected Blunt.

“Just so, June it was. Now, as I was saying, it wasn’t you with Mr. Ackroyd at nine-thirty this evening?”

Blunt shook his head.

“Never saw him after dinner,” he volunteered.

The inspector turned once more to Raymond.

“You didn’t overhear any of the conversation going on, did you, sir?”

“I did catch just a fragment of it,” said the secretary, “and, supposing as I did that it was Dr. Sheppard who was with Mr. Ackroyd, that fragment struck me as distinctly odd. As far as I can remember, the exact words were these. Mr. Ackroyd was speaking. ‘The calls on my purse have been so frequent of late’—that is what he was saying—‘of late, that I fear it is impossible for me to accede to your request….’ I went away again at once, of course, so did not hear any more. But I rather wondered because Dr. Sheppard——”

“——Does not ask for loans for himself or subscriptions for others,” I finished.

“A demand for money,” said the inspector musingly. “It may be that here we have a very important clew.” He turned to the butler. “You say, Parker, that nobody was admitted by the front door this evening?”

“That’s what I say, sir.”

“Then it seems almost certain that Mr. Ackroyd himself must have admitted this stranger. But I don’t quite see——”

The inspector went into a kind of day-dream for some minutes.

“One thing’s clear,” he said at length, rousing himself from his absorption. “Mr. Ackroyd was alive and well at nine-thirty. That is the last moment at which he is known to have been alive.”

Parker gave vent to an apologetic cough which brought the inspector’s eyes on him at once.

“Well?” he said sharply.

“If you’ll excuse me, sir, Miss Flora saw him after that.”

“Miss Flora?”

“Yes, sir. About a quarter to ten that would be. It was after that that she told me Mr. Ackroyd wasn’t to be disturbed again to-night.”

“Did he send her to you with that message?”

“Not exactly, sir. I was bringing a tray with soda and whisky when Miss Flora, who was just coming out of this room, stopped me and said her uncle didn’t want to be disturbed.”

The inspector looked at the butler with rather closer attention than he had bestowed on him up to now.

“You’d already been told that Mr. Ackroyd didn’t want to be disturbed, hadn’t you?”

Parker began to stammer. His hands shook.

“Yes, sir. Yes, sir. Quite so, sir.”

“And yet you were proposing to do so?”

“I’d forgotten, sir. At least I mean, I always bring the whisky and soda about that time, sir, and ask if there’s anything more, and I thought—well, I was doing as usual without thinking.”

It was at this moment that it began to dawn upon me that Parker was most suspiciously flustered. The man was shaking and twitching all over.

“H’m,” said the inspector. “I must see Miss Ackroyd at once. For the moment we’ll leave this room exactly as it is. I can return here after I’ve heard what Miss Ackroyd has to tell me. I shall just take the precaution of shutting and bolting the window.”

This precaution accomplished, he led the way into the hall and we followed him. He paused a moment, as he glanced up at the little staircase, then spoke over his shoulder to the constable.

“Jones, you’d better stay here. Don’t let any one go into that room.”

Parker interposed deferentially.

“If you’ll excuse me, sir. If you were to lock the door into the main hall, nobody could gain access to this part. That staircase leads only to Mr. Ackroyd’s bedroom and bathroom. There is no communication with the other part of the house. There once was a door through, but Mr. Ackroyd had it blocked up. He liked to feel that his suite was entirely private.”

To make things clear and explain the position, I have appended a rough sketch of the right-hand wing of the house. The small staircase leads, as Parker explained, to a big bedroom (made by two being knocked into one) and an adjoining bathroom and lavatory.

The inspector took in the position at a glance. We went through into the large hall and he locked the door behind him, slipping the key into his pocket. Then he gave the constable some low-voiced instructions, and the latter prepared to depart.

“We must get busy on those shoe tracks,” explained the inspector. “But first of all, I must have a word with Miss Ackroyd. She was the last person to see her uncle alive. Does she know yet?”

Raymond shook his head.

“Well, no need to tell her for another five minutes. She can answer my questions better without being upset by knowing the truth about her uncle. Tell her there’s been a burglary, and ask her if she would mind dressing and coming down to answer a few questions.”

It was Raymond who went upstairs on this errand.

“Miss Ackroyd will be down in a minute,” he said, when he returned. “I told her just what you suggested.”

In less than five minutes Flora descended the staircase. She was wrapped in a pale pink silk kimono. She looked anxious and excited.

The inspector stepped forward.

“Good-evening, Miss Ackroyd,” he said civilly. “We’re afraid there’s been an attempt at robbery, and we want you to help us. What’s this room—the billiard room? Come in here and sit down.”

Flora sat down composedly on the wide divan which ran the length of the wall, and looked up at the inspector.

“I don’t quite understand. What has been stolen? What do you want me to tell you?”

“It’s just this, Miss Ackroyd. Parker here says you came out of your uncle’s study at about a quarter to ten. Is that right?”

“Quite right. I had been to say good-night to him.”

“And the time is correct?”

“Well, it must have been about then. I can’t say exactly. It might have been later.”

“Was your uncle alone, or was there any one with him?”

“He was alone. Dr. Sheppard had gone.”

“Did you happen to notice whether the window was open or shut?”

Flora shook her head.

“I can’t say. The curtains were drawn.”

“Exactly. And your uncle seemed quite as usual?”

“I think so.”

“Do you mind telling us exactly what passed between you?”

Flora paused a minute, as though to collect her recollections.

“I went in and said, ‘Good-night, uncle, I’m going to bed now. I’m tired to-night.’ He gave a sort of grunt, and—I went over and kissed him, and he said something about my looking nice in the frock I had on, and then he told me to run away as he was busy. So I went.”

“Did he ask specially not to be disturbed?”

“Oh! yes, I forgot. He said: ‘Tell Parker I don’t want anything more to-night, and that he’s not to disturb me.’ I met Parker just outside the door and gave him uncle’s message.”

“Just so,” said the inspector.

“Won’t you tell me what it is that has been stolen?”

“We’re not quite—certain,” said the inspector hesitatingly.

A wide look of alarm came into the girl’s eyes. She started up.

“What is it? You’re hiding something from me?”

Moving in his usual unobtrusive manner, Hector Blunt came between her and the inspector. She half stretched out her hand, and he took it in both of his, patting it as though she were a very small child, and she turned to him as though something in his stolid, rocklike demeanor promised comfort and safety.

“It’s bad news, Flora,” he said quietly. “Bad news for all of us. Your Uncle Roger——”

“Yes?”

“It will be a shock to you. Bound to be. Poor Roger’s dead.”

Flora drew away from him, her eyes dilating with horror.

“When?” she whispered. “When?”

“Very soon after you left him, I’m afraid,” said Blunt gravely.

Flora raised her hand to her throat, gave a little cry, and I hurried to catch her as she fell. She had fainted, and Blunt and I carried her upstairs and laid her on her bed. Then I got him to wake Mrs. Ackroyd and tell her the news. Flora soon revived, and I brought her mother to her, telling her what to do for the girl. Then I hurried downstairs again.

CHAPTER VI

THE TUNISIAN DAGGER

I met the inspector just coming from the door which led into the kitchen quarters.

“How’s the young lady, doctor?”

“Coming round nicely. Her mother’s with her.”

“That’s good. I’ve been questioning the servants. They all declare that no one has been to the back door to-night. Your description of that stranger was rather vague. Can’t you give us something more definite to go upon?”

“I’m afraid not,” I said regretfully. “It was a dark night, you see, and the fellow had his coat collar well pulled up and his hat squashed down over his eyes.”

“H’m,” said the inspector. “Looked as though he wanted to conceal his face. Sure it was no one you know?”

I replied in the negative, but not as decidedly as I might have done. I remembered my impression that the stranger’s voice was not unfamiliar to me. I explained this rather haltingly to the inspector.

“It was a rough, uneducated voice, you say?”

I agreed, but it occurred to me that the roughness had been of an almost exaggerated quality. If, as the inspector thought, the man had wished to hide his face, he might equally well have tried to disguise his voice.

“Do you mind coming into the study with me again, doctor? There are one or two things I want to ask you.”

I acquiesced. Inspector Davis unlocked the door of the lobby, we passed through, and he locked the door again behind him.

“We don’t want to be disturbed,” he said grimly. “And we don’t want any eavesdropping either. What’s all this about blackmail?”

“Blackmail!” I exclaimed, very much startled.

“Is it an effort of Parker’s imagination? Or is there something in it?”

“If Parker heard anything about blackmail,” I said slowly, “he must have been listening outside this door with his ear glued against the keyhole.”

Davis nodded.

“Nothing more likely. You see, I’ve been instituting a few inquiries as to what Parker has been doing with himself this evening. To tell the truth, I didn’t like his manner. The man knows something. When I began to question him, he got the wind up, and plumped out some garbled story of blackmail.”

I took an instant decision.

“I’m rather glad you’ve brought the matter up,” I said. “I’ve been trying to decide whether to make a clean breast of things or not. I’d already practically decided to tell you everything, but I was going to wait for a favorable opportunity. You might as well have it now.”

And then and there I narrated the whole events of the evening as I have set them down here. The inspector listened keenly, occasionally interjecting a question.

“Most extraordinary story I ever heard,” he said, when I had finished. “And you say that letter has completely disappeared? It looks bad—it looks very bad indeed. It gives us what we’ve been looking for—a motive for the murder.”

I nodded.

“I realize that.”

“You say that Mr. Ackroyd hinted at a suspicion he had that some member of his household was involved? Household’s rather an elastic term.”

“You don’t think that Parker himself might be the man we’re after?” I suggested.

“It looks very like it. He was obviously listening at the door when you came out. Then Miss Ackroyd came across him later bent on entering the study. Say he tried again when she was safely out of the way. He stabbed Ackroyd, locked the door on the inside, opened the window, and got out that way, and went round to a side door which he had previously left open. How’s that?”

“There’s only one thing against it,” I said slowly. “If Ackroyd went on reading that letter as soon as I left, as he intended to do, I don’t see him continuing to sit on here and turn things over in his mind for another hour. He’d have had Parker in at once, accused him then and there, and there would have been a fine old uproar. Remember, Ackroyd was a man of choleric temper.”

“Mightn’t have had time to go on with the letter just then,” suggested the inspector. “We know some one was with him at half-past nine. If that visitor turned up as soon as you left, and after he went, Miss Ackroyd came in to say good-night—well, he wouldn’t be able to go on with the letter until close upon ten o’clock.”

“And the telephone call?”

“Parker sent that all right—perhaps before he thought of the locked door and open window. Then he changed his mind—or got in a panic—and decided to deny all knowledge of it. That was it, depend upon it.”

“Ye-es,” I said rather doubtfully.

“Anyway, we can find out the truth about the telephone call from the exchange. If it was put through from here, I don’t see how any one else but Parker could have sent it. Depend upon it, he’s our man. But keep it dark—we don’t want to alarm him just yet, till we’ve got all the evidence. I’ll see to it he doesn’t give us the slip. To all appearances we’ll be concentrating on your mysterious stranger.”

He rose from where he had been sitting astride the chair belonging to the desk, and crossed over to the still form in the arm-chair.

“The weapon ought to give us a clew,” he remarked, looking up. “It’s something quite unique—a curio, I should think, by the look of it.”

He bent down, surveying the handle attentively, and I heard him give a grunt of satisfaction. Then, very gingerly, he pressed his hands down below the hilt and drew the blade out from the wound. Still carrying it so as not to touch the handle, he placed it in a wide china mug which adorned the mantelpiece.

“Yes,” he said, nodding at it. “Quite a work of art. There can’t be many of them about.”

It was indeed a beautiful object. A narrow, tapering blade, and a hilt of elaborately intertwined metals of curious and careful workmanship. He touched the blade gingerly with his finger, testing its sharpness, and made an appreciative grimace.

“Lord, what an edge,” he exclaimed. “A child could drive that into a man—as easy as cutting butter. A dangerous sort of toy to have about.”

“May I examine the body properly now?” I asked.

He nodded.

“Go ahead.”

I made a thorough examination.

“Well?” said the inspector, when I had finished.

“I’ll spare you the technical language,” I said. “We’ll keep that for the inquest. The blow was delivered by a right-handed man standing behind him, and death must have been instantaneous. By the expression on the dead man’s face, I should say that the blow was quite unexpected. He probably died without knowing who his assailant was.”

“Butlers can creep about as soft-footed as cats,” said Inspector Davis. “There’s not going to be much mystery about this crime. Take a look at the hilt of that dagger.”

I took the look.

“I dare say they’re not apparent to you, but I can see them clearly enough.” He lowered his voice. “Fingerprints!”

He stood off a few steps to judge of his effect.

“Yes,” I said mildly. “I guessed that.”

I do not see why I should be supposed to be totally devoid of intelligence. After all, I read detective stories, and the newspapers, and am a man of quite average ability. If there had been toe marks on the dagger handle, now, that would have been quite a different thing. I would then have registered any amount of surprise and awe.

I think the inspector was annoyed with me for declining to get thrilled. He picked up the china mug and invited me to accompany him to the billiard room.

“I want to see if Mr. Raymond can tell us anything about this dagger,” he explained.

Locking the outer door behind us again, we made our way to the billiard room, where we found Geoffrey Raymond. The inspector held up his exhibit.

“Ever seen this before, Mr. Raymond?”

“Why—I believe—I’m almost sure that is a curio given to Mr. Ackroyd by Major Blunt. It comes from Morocco—no, Tunis. So the crime was committed with that? What an extraordinary thing. It seems almost impossible, and yet there could hardly be two daggers the same. May I fetch Major Blunt?”

Without waiting for an answer, he hurried off.

“Nice young fellow that,” said the inspector. “Something honest and ingenuous about him.”

I agreed. In the two years that Geoffrey Raymond has been secretary to Ackroyd, I have never seen him ruffled or out of temper. And he has been, I know, a most efficient secretary.

In a minute or two Raymond returned, accompanied by Blunt.

“I was right,” said Raymond excitedly. “It is the Tunisian dagger.”

“Major Blunt hasn’t looked at it yet,” objected the inspector.

“Saw it the moment I came into the study,” said the quiet man.

“You recognized it then?”

Blunt nodded.

“You said nothing about it,” said the inspector suspiciously.

“Wrong moment,” said Blunt. “Lot of harm done by blurting out things at the wrong time.”

He returned the inspector’s stare placidly enough.

The latter grunted at last and turned away. He brought the dagger over to Blunt.

“You’re quite sure about it, sir. You identify it positively?”

“Absolutely. No doubt whatever.”

“Where was this—er—curio usually kept? Can you tell me that, sir?”

It was the secretary who answered.

“In the silver table in the drawing-room.”

“What?” I exclaimed.

The others looked at me.

“Yes, doctor?” said the inspector encouragingly.

“It’s nothing.”

“Yes, doctor?” said the inspector again, still more encouragingly.

“It’s so trivial,” I explained apologetically. “Only that when I arrived last night for dinner I heard the lid of the silver table being shut down in the drawing-room.”

I saw profound skepticism and a trace of suspicion on the inspector’s countenance.

“How did you know it was the silver table lid?”

I was forced to explain in detail—a long, tedious explanation which I would infinitely rather not have had to make.

The inspector heard me to the end.

“Was the dagger in its place when you were looking over the contents?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I can’t say I remember noticing it—but, of course, it may have been there all the time.”

“We’d better get hold of the housekeeper,” remarked the inspector, and pulled the bell.

A few minutes later Miss Russell, summoned by Parker, entered the room.

“I don’t think I went near the silver table,” she said, when the inspector had posed his question. “I was looking to see that all the flowers were fresh. Oh! yes, I remember now. The silver table was open—which it had no business to be, and I shut the lid down as I passed.”

She looked at him aggressively.

“I see,” said the inspector. “Can you tell me if this dagger was in its place then?”

Miss Russell looked at the weapon composedly.

“I can’t say, I’m sure,” she replied. “I didn’t stop to look. I knew the family would be down any minute, and I wanted to get away.”

“Thank you,” said the inspector.

There was just a trace of hesitation in his manner, as though he would have liked to question her further, but Miss Russell clearly accepted the words as a dismissal, and glided from the room.

“Rather a Tartar, I should fancy, eh?” said the inspector, looking after her. “Let me see. This silver table is in front of one of the windows, I think you said, doctor?”

Raymond answered for me.

“Yes, the left-hand window.”

“And the window was open?”

“They were both ajar.”

“Well, I don’t think we need go into the question much further. Somebody—I’ll just say somebody—could get that dagger any time he liked, and exactly when he got it doesn’t matter in the least. I’ll be coming up in the morning with the chief constable, Mr. Raymond. Until then, I’ll keep the key of that door. I want Colonel Melrose to see everything exactly as it is. I happen to know that he’s dining out the other side of the county, and, I believe, staying the night....”

We watched the inspector take up the jar.

“I shall have to pack this carefully,” he observed. “It’s going to be an important piece of evidence in more ways than one.”

A few minutes later as I came out of the billiard room with Raymond, the latter gave a low chuckle of amusement.

I felt the pressure of his hand on my arm, and followed the direction of his eyes. Inspector Davis seemed to be inviting Parker’s opinion of a small pocket diary.

“A little obvious,” murmured my companion. “So Parker is the suspect, is he? Shall we oblige Inspector Davis with a set of our fingerprints also?”

He took two cards from the card tray, wiped them with his silk handkerchief, then handed one to me and took the other himself. Then, with a grin, he handed them to the police inspector.

“Souvenirs,” he said. “No. 1, Dr. Sheppard; No. 2, my humble self. One from Major Blunt will be forthcoming in the morning.”

Youth is very buoyant. Even the brutal murder of his friend and employer could not dim Geoffrey Raymond’s spirits for long. Perhaps that is as it should be. I do not know. I have lost the quality of resilience long since myself.

It was very late when I got back, and I hoped that Caroline would have gone to bed. I might have known better.

She had hot cocoa waiting for me, and whilst I drank it, she extracted the whole history of the evening from me. I said nothing of the blackmailing business, but contented myself with giving her the facts of the murder.

“The police suspect Parker,” I said, as I rose to my feet and prepared to ascend to bed. “There seems a fairly clear case against him.”

“Parker!” said my sister. “Fiddlesticks! That inspector must be a perfect fool. Parker indeed! Don’t tell me.”

With which obscure pronouncement we went up to bed.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘The Murder of Roger Ackroyd’ by Agatha Christie

Genre: Adult Fiction – Crime/Mystery

Published: 1926

Format: Paperback

Rating: ★★★★★

An absolutely brilliant mystery! Agatha Christie hasn’t managed to disappoint me yet and this is the best I’ve read so far. Her plotting of a murder mystery and the development of characters and their involvement in the plot is so intricate and nuanced that sometimes you’re not sure who you’re supposed to be…

View On WordPress

#Agatha Christie#Book#Book Review#Crime#Fiction#Hercule Poirot#Murder#Murder Mystery#murder of roger ackroyd#Mystery#Novel#Poirot#Review#roger ackroyd

0 notes

Text

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Deluxe Edition by Agatha Christie #NetGalley #eARCReview #BookReview #HerculePoirot

One of #AgathaChristie's most famous books is being released in #DEluxeEdition. I can see this as a perfect #Christmasgift for any book lover #TheMurderofRogerAckroyd #HerculePoirot #MurderMystery #ClassicBooks #bookreview #NetGalley #ARCReview #newbook

From Amazon.com: A beautifully produced edition of the world’s greatest crime writer’s best and most influential mystery, which changed the game with an unprecedented plot twistWith its famously shocking ending, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is one of Agatha Christie’s greatest mysteries, and the book that changed her career. One evening the wealthy Roger Ackroyd is discovered slumped in his…

View On WordPress

#1970&039;s Movies#1980&039;s Movies#1990&039;s Television#Agatha Christie#Albert Finney#David Suchet#Funny Little Belgian#Hercule Poirot#Murder Mystery#Mystery#Peter Ustinov#Roger Ackroyd#The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

0 notes

Text

(´ε` )♡

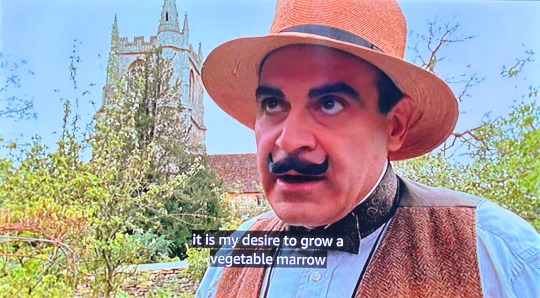

AGATHA CHRISTIE'S POIROT (1989 - 2013)

#poirot#hercule poirot#agatha christie#david suchet#tvedit#perioddramaedit#poirotedit#*edit#poirot 1x06: triangle at rhodes#poirot 1x10: the dream#poirot 3x01: the mysterious affair at styles#poirot 4x01: the abc murders#poirot 5x04: the case of the missing will#poirot 6x01: hercule poirot's christmas#poirot 10x04: taken at the flood#poirot 7x01: the murder of roger ackroyd#HAVE SOME POIROT KISSES <3<3#the way he looks at the lady in the 6th gif *o*#or in the 8th gif when he meets her eyes#EXCUSE ME sir <3

520 notes

·

View notes

Text

Headcannon Virgil likes true crime but it always makes him really anxious before trying to sleep. Logan introduces him to Agatha Christie novels which have just enough murder and crime to keep Virgil's interest, but aren't written in a scary enough way for him to have a panic attack over it. He's downloaded every novel to listen to as he goes to bed

#sanders sides#logan sanders#virgil sanders#headcanon#analogical#platonic or romantic#your choice really#it started after the first q&a where logan said his favourite novel was the murder of roger ackroyd#and virgil really needed to know the ending#so he read it and just slowly got addicted

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the murder of roger ackroyd#agatha christie#crime#book poll#have you read this book poll#polls#tw blood

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd

Agatha Christie

FYI - this is 1 of 12 vintage paperback classics that comprise our current giveaw@y.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by the lovely @lewishcmilton to list my top 9 books, thank you darling!! 🫶🏼

(i also did 10 because I couldn't choose and also i have so many more i couldn't fit them all 😭)

tagging @lewisrises (can't wait to see what you pick!!) @enchantelewis @enchantestuff @lostinlewis @lucent-knight and @grandestrategia to do this if you want <3

#tag games#games#books#beloved#toni morrison#pride and prejudice#jane austen#Agatha christie#the murder of roger ackroyd#crime and punishment#fyodor dostoyevsky bsd#the secret history donna tart#if we were villain#wuthering heights#emily bronte#dead poets society#the silent patient

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Agatha Christie.

Chapter 1-2

CHAPTER I

DR. SHEPPARD AT THE BREAKFAST TABLE

Mrs. Ferrars died on the night of the 16th–17th September—a Thursday. I was sent for at eight o’clock on the morning of Friday the 17th. There was nothing to be done. She had been dead some hours.

It was just a few minutes after nine when I reached home once more. I opened the front door with my latch-key, and purposely delayed a few moments in the hall, hanging up my hat and the light overcoat that I had deemed a wise precaution against the chill of an early autumn morning. To tell the truth, I was considerably upset and worried. I am not going to pretend that at that moment I foresaw the events of the next few weeks. I emphatically did not do so. But my instinct told me that there were stirring times ahead.

From the dining-room on my left there came the rattle of tea-cups and the short, dry cough of my sister Caroline.

“Is that you, James?” she called.

An unnecessary question, since who else could it be? To tell the truth, it was precisely my sister Caroline who was the cause of my few minutes’ delay. The motto of the mongoose family, so Mr. Kipling tells us, is: “Go and find out.” If Caroline ever adopts a crest, I should certainly suggest a mongoose rampant. One might omit the first part of the motto. Caroline can do any amount of finding out by sitting placidly at home. I don’t know how she manages it, but there it is. I suspect that the servants and the tradesmen constitute her Intelligence Corps. When she goes out, it is not to gather in information, but to spread it. At that, too, she is amazingly expert.

It was really this last named trait of hers which was causing me these pangs of indecision. Whatever I told Caroline now concerning the demise of Mrs. Ferrars would be common knowledge all over the village within the space of an hour and a half. As a professional man, I naturally aim at discretion. Therefore I have got into the habit of continually withholding all information possible from my sister. She usually finds out just the same, but I have the moral satisfaction of knowing that I am in no way to blame.

Mrs. Ferrars’ husband died just over a year ago, and Caroline has constantly asserted, without the least foundation for the assertion, that his wife poisoned him.

She scorns my invariable rejoinder that Mr. Ferrars died of acute gastritis, helped on by habitual over-indulgence in alcoholic beverages. The symptoms of gastritis and arsenical poisoning are not, I agree, unlike, but Caroline bases her accusation on quite different lines.

“You’ve only got to look at her,” I have heard her say.

Mrs. Ferrars, though not in her first youth, was a very attractive woman, and her clothes, though simple, always seemed to fit her very well, but all the same, lots of women buy their clothes in Paris and have not, on that account, necessarily poisoned their husbands.

As I stood hesitating in the hall, with all this passing through my mind, Caroline’s voice came again, with a sharper note in it.

“What on earth are you doing out there, James? Why don’t you come and get your breakfast?”

“Just coming, my dear,” I said hastily. “I’ve been hanging up my overcoat.”

“You could have hung up half a dozen overcoats in this time.”

She was quite right. I could have.

I walked into the dining-room, gave Caroline the accustomed peck on the cheek, and sat down to eggs and bacon. The bacon was rather cold.

“You’ve had an early call,” remarked Caroline.

“Yes,” I said. “King’s Paddock. Mrs. Ferrars.”

“I know,” said my sister.

“How did you know?”

“Annie told me.”

Annie is the house parlormaid. A nice girl, but an inveterate talker.

There was a pause. I continued to eat eggs and bacon. My sister’s nose, which is long and thin, quivered a little at the tip, as it always does when she is interested or excited over anything.

“Well?” she demanded.

“A bad business. Nothing to be done. Must have died in her sleep.”

“I know,” said my sister again.

This time I was annoyed.

“You can’t know,” I snapped. “I didn’t know myself until I got there, and I haven’t mentioned it to a soul yet. If that girl Annie knows, she must be a clairvoyant.”

“It wasn’t Annie who told me. It was the milkman. He had it from the Ferrars’ cook.”

As I say, there is no need for Caroline to go out to get information. She sits at home, and it comes to her.

My sister continued:

“What did she die of? Heart failure?”

“Didn’t the milkman tell you that?” I inquired sarcastically.

Sarcasm is wasted on Caroline. She takes it seriously and answers accordingly.

“He didn’t know,” she explained.

After all, Caroline was bound to hear sooner or later. She might as well hear from me.

“She died of an overdose of veronal. She’s been taking it lately for sleeplessness. Must have taken too much.”

“Nonsense,” said Caroline immediately. “She took it on purpose. Don’t tell me!”

It is odd how, when you have a secret belief of your own which you do not wish to acknowledge, the voicing of it by some one else will rouse you to a fury of denial. I burst immediately into indignant speech.

“There you go again,” I said. “Rushing along without rhyme or reason. Why on earth should Mrs. Ferrars wish to commit suicide? A widow, fairly young still, very well off, good health, and nothing to do but enjoy life. It’s absurd.”

“Not at all. Even you must have noticed how different she has been looking lately. It’s been coming on for the last six months. She’s looked positively hag-ridden. And you have just admitted that she hasn’t been able to sleep.”

“What is your diagnosis?” I demanded coldly. “An unfortunate love affair, I suppose?”

My sister shook her head.

“Remorse,” she said, with great gusto.

“Remorse?”

“Yes. You never would believe me when I told you she poisoned her husband. I’m more than ever convinced of it now.”

“I don’t think you’re very logical,” I objected. “Surely if a woman committed a crime like murder, she’d be sufficiently cold-blooded to enjoy the fruits of it without any weak-minded sentimentality such as repentance.”

Caroline shook her head.

“There probably are women like that—but Mrs. Ferrars wasn’t one of them. She was a mass of nerves. An overmastering impulse drove her on to get rid of her husband because she was the sort of person who simply can’t endure suffering of any kind, and there’s no doubt that the wife of a man like Ashley Ferrars must have had to suffer a good deal——”

I nodded.

“And ever since she’s been haunted by what she did. I can’t help feeling sorry for her.”

I don’t think Caroline ever felt sorry for Mrs. Ferrars whilst she was alive. Now that she has gone where (presumably) Paris frocks can no longer be worn, Caroline is prepared to indulge in the softer emotions of pity and comprehension.

I told her firmly that her whole idea was nonsense. I was all the more firm because I secretly agreed with some part, at least, of what she had said. But it is all wrong that Caroline should arrive at the truth simply by a kind of inspired guesswork. I wasn’t going to encourage that sort of thing. She will go round the village airing her views, and every one will think that she is doing so on medical data supplied by me. Life is very trying.

“Nonsense,” said Caroline, in reply to my strictures. “You’ll see. Ten to one she’s left a letter confessing everything.”

“She didn’t leave a letter of any kind,” I said sharply, and not seeing where the admission was going to land me.

“Oh!” said Caroline. “So you did inquire about that, did you? I believe, James, that in your heart of hearts, you think very much as I do. You’re a precious old humbug.”

“One always has to take the possibility of suicide into consideration,” I said repressively.

“Will there be an inquest?”

“There may be. It all depends. If I am able to declare myself absolutely satisfied that the overdose was taken accidentally, an inquest might be dispensed with.”

“And are you absolutely satisfied?” asked my sister shrewdly.

I did not answer, but got up from table.

CHAPTER II

WHO’S WHO IN KING’S ABBOT

Before I proceed further with what I said to Caroline and what Caroline said to me, it might be as well to give some idea of what I should describe as our local geography. Our village, King’s Abbot, is, I imagine, very much like any other village. Our big town is Cranchester, nine miles away. We have a large railway station, a small post office, and two rival “General Stores.” Able-bodied men are apt to leave the place early in life, but we are rich in unmarried ladies and retired military officers. Our hobbies and recreations can be summed up in the one word, “gossip.”

There are only two houses of any importance in King’s Abbot. One is King’s Paddock, left to Mrs. Ferrars by her late husband. The other, Fernly Park, is owned by Roger Ackroyd. Ackroyd has always interested me by being a man more impossibly like a country squire than any country squire could really be. He reminds one of the red-faced sportsmen who always appeared early in the first act of an old-fashioned musical comedy, the setting being the village green. They usually sang a song about going up to London. Nowadays we have revues, and the country squire has died out of musical fashion.

Of course, Ackroyd is not really a country squire. He is an immensely successful manufacturer of (I think) wagon wheels. He is a man of nearly fifty years of age, rubicund of face and genial of manner. He is hand and glove with the vicar, subscribes liberally to parish funds (though rumor has it that he is extremely mean in personal expenditure), encourages cricket matches, Lads’ Clubs, and Disabled Soldiers’ Institutes. He is, in fact, the life and soul of our peaceful village of King’s Abbot.

Now when Roger Ackroyd was a lad of twenty-one, he fell in love with, and married, a beautiful woman some five or six years his senior. Her name was Paton, and she was a widow with one child. The history of the marriage was short and painful. To put it bluntly, Mrs. Ackroyd was a dipsomaniac. She succeeded in drinking herself into her grave four years after her marriage.

In the years that followed, Ackroyd showed no disposition to make a second matrimonial adventure. His wife’s child by her first marriage was only seven years old when his mother died. He is now twenty-five. Ackroyd has always regarded him as his own son, and has brought him up accordingly, but he has been a wild lad and a continual source of worry and trouble to his stepfather. Nevertheless we are all very fond of Ralph Paton in King’s Abbot. He is such a good-looking youngster for one thing.

As I said before, we are ready enough to gossip in our village. Everybody noticed from the first that Ackroyd and Mrs. Ferrars got on very well together. After her husband’s death, the intimacy became more marked. They were always seen about together, and it was freely conjectured that at the end of her period of mourning, Mrs. Ferrars would become Mrs. Roger Ackroyd. It was felt, indeed, that there was a certain fitness in the thing. Roger Ackroyd’s wife had admittedly died of drink. Ashley Ferrars had been a drunkard for many years before his death. It was only fitting that these two victims of alcoholic excess should make up to each other for all that they had previously endured at the hands of their former spouses.

The Ferrars only came to live here just over a year ago, but a halo of gossip has surrounded Ackroyd for many years past. All the time that Ralph Paton was growing up to manhood, a series of lady housekeepers presided over Ackroyd’s establishment, and each in turn was regarded with lively suspicion by Caroline and her cronies. It is not too much to say that for at least fifteen years the whole village has confidently expected Ackroyd to marry one of his housekeepers. The last of them, a redoubtable lady called Miss Russell, has reigned undisputed for five years, twice as long as any of her predecessors. It is felt that but for the advent of Mrs. Ferrars, Ackroyd could hardly have escaped. That—and one other factor—the unexpected arrival of a widowed sister-in-law with her daughter from Canada. Mrs. Cecil Ackroyd, widow of Ackroyd’s ne’er-do-well younger brother, has taken up her residence at Fernly Park, and has succeeded, according to Caroline, in putting Miss Russell in her proper place.

I don’t know exactly what a “proper place” constitutes—it sounds chilly and unpleasant—but I know that Miss Russell goes about with pinched lips, and what I can only describe as an acid smile, and that she professes the utmost sympathy for “poor Mrs. Ackroyd—dependent on the charity of her husband’s brother. The bread of charity is so bitter, is it not? I should be quite miserable if I did not work for my living.”

I don’t know what Mrs. Cecil Ackroyd thought of the Ferrars affair when it came on the tapis. It was clearly to her advantage that Ackroyd should remain unmarried. She was always very charming—not to say gushing—to Mrs. Ferrars when they met. Caroline says that proves less than nothing.

Such have been our preoccupations in King’s Abbot for the last few years. We have discussed Ackroyd and his affairs from every standpoint. Mrs. Ferrars has fitted into her place in the scheme.

Now there has been a rearrangement of the kaleidoscope. From a mild discussion of probable wedding presents, we have been jerked into the midst of tragedy.

Revolving these and sundry other matters in my mind, I went mechanically on my round. I had no cases of special interest to attend, which was, perhaps, as well, for my thoughts returned again and again to the mystery of Mrs. Ferrars’s death. Had she taken her own life? Surely, if she had done so, she would have left some word behind to say what she contemplated doing? Women, in my experience, if they once reach the determination to commit suicide, usually wish to reveal the state of mind that led to the fatal action. They covet the limelight.

When had I last seen her? Not for over a week. Her manner then had been normal enough considering—well—considering everything.

Then I suddenly remembered that I had seen her, though not to speak to, only yesterday. She had been walking with Ralph Paton, and I had been surprised because I had had no idea that he was likely to be in King’s Abbot. I thought, indeed, that he had quarreled finally with his stepfather. Nothing had been seen of him down here for nearly six months. They had been walking along, side by side, their heads close together, and she had been talking very earnestly.

I think I can safely say that it was at this moment that a foreboding of the future first swept over me. Nothing tangible as yet—but a vague premonition of the way things were setting. That earnest tête-à-tête between Ralph Paton and Mrs. Ferrars the day before struck me disagreeably.

I was still thinking of it when I came face to face with Roger Ackroyd.

“Sheppard!” he exclaimed. “Just the man I wanted to get hold of. This is a terrible business.”

“You’ve heard then?”

He nodded. He had felt the blow keenly, I could see. His big red cheeks seemed to have fallen in, and he looked a positive wreck of his usual jolly, healthy self.

“It’s worse than you know,” he said quietly. “Look here, Sheppard, I’ve got to talk to you. Can you come back with me now?”

“Hardly. I’ve got three patients to see still, and I must be back by twelve to see my surgery patients.”

“Then this afternoon—no, better still, dine to-night. At 7.30? Will that suit you?”

“Yes—I can manage that all right. What’s wrong? Is it Ralph?”

I hardly knew why I said that—except, perhaps, that it had so often been Ralph.

Ackroyd stared blankly at me as though he hardly understood. I began to realize that there must be something very wrong indeed somewhere. I had never seen Ackroyd so upset before.

“Ralph?” he said vaguely. “Oh! no, it’s not Ralph. Ralph’s in London——Damn! Here’s old Miss Ganett coming. I don’t want to have to talk to her about this ghastly business. See you to-night, Sheppard. Seven-thirty.”

I nodded, and he hurried away, leaving me wondering. Ralph in London? But he had certainly been in King’s Abbot the preceding afternoon. He must have gone back to town last night or early this morning, and yet Ackroyd’s manner had conveyed quite a different impression. He had spoken as though Ralph had not been near the place for months.

I had no time to puzzle the matter out further. Miss Ganett was upon me, thirsting for information. Miss Ganett has all the characteristics of my sister Caroline, but she lacks that unerring aim in jumping to conclusions which lends a touch of greatness to Caroline’s maneuvers. Miss Ganett was breathless and interrogatory.

Wasn’t it sad about poor dear Mrs. Ferrars? A lot of people were saying she had been a confirmed drug-taker for years. So wicked the way people went about saying things. And yet, the worst of it was, there was usually a grain of truth somewhere in these wild statements. No smoke without fire! They were saying too that Mr. Ackroyd had found out about it, and had broken off the engagement—because there was an engagement. She, Miss Ganett, had proof positive of that. Of course I must know all about it—doctors always did—but they never tell?

And all this with a sharp beady eye on me to see how I reacted to these suggestions. Fortunately long association with Caroline has led me to preserve an impassive countenance, and to be ready with small non-committal remarks.

On this occasion I congratulated Miss Ganett on not joining in ill-natured gossip. Rather a neat counterattack, I thought. It left her in difficulties, and before she could pull herself together, I had passed on.

I went home thoughtful, to find several patients waiting for me in the surgery.

I had dismissed the last of them, as I thought, and was just contemplating a few minutes in the garden before lunch when I perceived one more patient waiting for me. She rose and came towards me as I stood somewhat surprised.

I don’t know why I should have been, except that there is a suggestion of cast iron about Miss Russell, a something that is above the ills of the flesh.

Ackroyd’s housekeeper is a tall woman, handsome but forbidding in appearance. She has a stern eye, and lips that shut tightly, and I feel that if I were an under housemaid or a kitchenmaid I should run for my life whenever I heard her coming.

“Good morning, Dr. Sheppard,” said Miss Russell. “I should be much obliged if you would take a look at my knee.”

I took a look, but, truth to tell, I was very little wiser when I had done so. Miss Russell’s account of vague pains was so unconvincing that with a woman of less integrity of character I should have suspected a trumped-up tale. It did cross my mind for one moment that Miss Russell might have deliberately invented this affection of the knee in order to pump me on the subject of Mrs. Ferrars’s death, but I soon saw that there, at least, I had misjudged her. She made a brief reference to the tragedy, nothing more. Yet she certainly seemed disposed to linger and chat.

“Well, thank you very much for this bottle of liniment, doctor,” she said at last. “Not that I believe it will do the least good.”

I didn’t think it would either, but I protested in duty bound. After all, it couldn’t do any harm, and one must stick up for the tools of one’s trade.

“I don’t believe in all these drugs,” said Miss Russell, her eyes sweeping over my array of bottles disparagingly. “Drugs do a lot of harm. Look at the cocaine habit.”

“Well, as far as that goes——”

“It’s very prevalent in high society.”

I’m sure Miss Russell knows far more about high society than I do. I didn’t attempt to argue with her.

“Just tell me this, doctor,” said Miss Russell. “Suppose you are really a slave of the drug habit. Is there any cure?”

One cannot answer a question like that offhand. I gave her a short lecture on the subject, and she listened with close attention. I still suspected her of seeking information about Mrs. Ferrars.

“Now, veronal, for instance——” I proceeded.

But, strangely enough, she didn’t seem interested in veronal. Instead she changed the subject, and asked me if it was true that there were certain poisons so rare as to baffle detection.

“Ah!” I said. “You’ve been reading detective stories.”

She admitted that she had.

“The essence of a detective story,” I said, “is to have a rare poison—if possible something from South America, that nobody has ever heard of—something that one obscure tribe of savages use to poison their arrows with. Death is instantaneous, and Western science is powerless to detect it. That is the kind of thing you mean?”

“Yes. Is there really such a thing?”

I shook my head regretfully.

“I’m afraid there isn’t. There’s curare, of course.”

I told her a good deal about curare, but she seemed to have lost interest once more. She asked me if I had any in my poison cupboard, and when I replied in the negative I fancy I fell in her estimation.

She said she must be getting back, and I saw her out at the surgery door just as the luncheon gong went.

I should never have suspected Miss Russell of a fondness for detective stories. It pleases me very much to think of her stepping out of the housekeeper’s room to rebuke a delinquent housemaid, and then returning to a comfortable perusal of The Mystery of the Seventh Death, or something of the kind.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was considering how an unreliable omniscient narrator might present in a story and realized that it was literally just Les Mis.

#les mis#thicc vicc#thicctor hugo#vicky huge-hoe#but yeah like a story where the narrators perception of events is just so incrediblt skewed#that the reader is led to the entirely wrong conclusion about Everything#despite having all the facts#I Just Think It'd Be Neat#Hugo is just unreliable because he decides to handwave details like what happened to JVJ's niblings#murder of roger ackroyd is also a good example tbh#well a decent one#the personality isn't as big as I'd like#you know those grinder screenshkts where the person who took the scree shot is the villain?#that energy combined with the voice of an autobiographer or Victor Hugo within the narrative

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

JOMP Book Photo Challenge || June || 17 || Female Author

Agatha Christie

#agatha christie#jompbpc#justonemorepage#book photo challenge#the murder of roger ackroyd#hallowe'en party#the abc murders#the body in the library#the murder at the vicarage#book photography#booklr#detective fiction#hercule poirot#miss marple#leerreadinglire

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another difference between Wuthering Heights and A True Novel is that Wuthering Heights is gloriously devoid of surprises. Nelly spells out the entire plot in Chapter 4. There are ambiguous points in the book and things to discover about it but they are more like multiple choice questions whose answers are left to the reader than like plot twists that change everything.

A True Novel is different. It very much has a central plot twist that changes everything, a sort of Roger Ackroyd or Rashomon but the reveal is related to “romance” rather than to “crime”.

I like both approaches, but they are decidedly different.

11 notes

·

View notes