#quenta noldorinwa

Text

Maglor only character explicitly named to be better than his father at something. That guy does not and will never have a single performance and craft anxiety in his life. Thank you.

197 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does canon indicate who is older: Elros or Elrond?

Birth Order of Elrond and Elros and Elrond

Good question. My instinct on this was no, canon does not indicate who is older, and indeed further research turned up nothing definitive. (If anyone has evidence to the contrary, please share it!) However, I uncovered a decent hint that Tolkien imagined Elros the elder.

[ETA: Please see this reblog for a revised answer that confirms the Elros theory!]

The fact that they are twins at all is not even in the published Silmarillion or The Lord of the Rings, which introduce them thus:

Bright Eärendil was then lord of the people that dwelt nigh to Sirion’s mouths; and he took to wife Elwing the fair, and she bore to him Elrond and Elros, who are called the Half-elven.

The Silmarillion, ‘Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath’

The sons of Eärendil were Elros and Elrond, the Peredhil or Half-elven.

The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A

Here, the order in which their names appear does not help us as we get both options.

It’s important to note here that Elros did not even exist from the conception of the mythology of Middle-earth. Elrond son of ‘Eärendel’ does not appear in any of the Lost Tales, but he does show up in the 1926 Sketch of the Mythology, the ‘Earliest’ Silmarillion (one day I’ll make post summarising all these texts, but in the meantime Table 2 at the end of this bio has a lot of them!). Elros does not join him until the next version of the Silmarillion,* the 1930 Quenta Noldorinwa. Here he is added in revisions to the text. In those revisions, his name comes first (‘Elros and Elrond’).

(*When I do not italicise Silmarillion, I am referring to the whole corpus of drafts. Italicised means the published book edited by Christopher Tolkien.)

The same sort of revision is made to Annal 325 of The Later Annals of Beleriand (referred to as AB 2 and written between 1930 and 1937). Christopher Tolkien notes that his father pencilled a note to change the original passage (which only mentions Elrond) to:

The Peringiul, the Half-elven, were born to Elwing wife of Eärendel, while Eärendel was at sea, the twin brethren Elrond and Elros.

The History of Middle-earth Vol. 5: The Lost Road, The Later Annals of Beleriand, Commentary on Annal 325.

Important! Christopher then notes, “The order was then inverted to ‘Elros and Elrond’.”

Note that the 1930 Quenta Noldorinwa is the main source for most of the last chapter of the published Silmarillion because Tolkien did not return to a full narrative of this section of the Silmarillion again. However, they are mentioned in the briefly sketched Tale of Years (1951-52), where it is again stated that they were twins and again they appear as ‘Elros and Elrond’.

[Added entry:] 528 [> 532] Elros and Elrond twin sons of Earendil born.*

The History of Middle-earth Vol. 11: The War of the Jewels, Tale of Years, Text ‘C’

*[> 532] means this entry was revised to 532, the date you will find in the timeline on Tolkien Gateway (which defaults to the ‘most recent’ revision). Note that The Tale of Years (the published portion of which only covers the 6th century of the First Age) is actually four consecutive drafts: dates are revised and the entries become increasingly detailed, but each draft ends earlier than the last (e.g. Text A goes to FA 600, Text D ends at FA 527). Most of the timelines you find online attempt to consolidate all four drafts — but worth bearing in mind that Tolkien never finalised these dates.

Finally: upon investigating the source text for that one instance, from the published Silmarillion, of Elrond appearing before Elros, I discovered that this was actually an editorial decision. Tolkien himself, as far as I could find, always listed Elros before Elrond.

Now, this is not, as I said, definitive evidence that Elros tumbled out of the womb first. But I’d say it suggests that Elros was the elder, since I can think of no other reason to consistently list them in this order (it’s not alphabetical, for example). And this, indeed, seems to be the fandom’s general consensus.

But, strictly based on canon, you are free to put them in either order. In fact, if you are someone who only takes the published Silmarillion as canon, you don’t even have to make them twins.

#elrond#elros#lotr appendices#the sketch of the mythology#quenta noldorinwa#the tale of years#history of middle-earth#anon

91 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The heart of Idril was turned towards [Tuor], and his to her; at which Maeglin ground his teeth, for he desired Idril, and despite his close kinship purposed to possess her; and she was the only heir of the king of Gondolin. Indeed in his heart he was already planning how he might oust Turgon and seize his throne; but Turgon loved and trusted him.

The Fall of Gondolin, Quenta Noldorinwa

#maeglin#idril#tuor#turgon#the silmarillion#the fall of gondolin#tolkien tag#fascinating dynamics between these four#quenta noldorinwa

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOOD, FIRE, & DEATH IN THE FIRST AGE -- THE FALL OF GONDOLIN HAS COME.

PIC INFO: Spotlight on a painting depicting "The Fall of Gondolin" (1990), and one to the darkest chapters in the history of the First Age, later used as cover art to "The Silmarillion" by J.R.R. Tolkien. Grafton Books, c. January 1992. Artwork by John Howe.

"Balrogs. Now these were demons with whips of flame and claws of steel by whom he tormented those of the Noldoli who durst withstand him in anything –and the Eldar have called them Malkarauki. But the rede that Meglin gave to Melko was that not all the host of the Orcs nor the Balrogs in their fierceness might by assault or siege hope ever to overthrow the walls and gates of Gondolin even if they availed to win unto the plain without."

-- J.R.R. TOLKIEN on "The Fall of Gondolin," the twenty-third chapter of the "Quenta Silmarillion" section within "The Silmarillion" (1977)

PAINTING OVERVIEW: "This painting was commissioned for the cover of "The Silmarillion." Gondolin is described as having beautiful white walls, which provide a welcome canvas for the dark masses of Morgoth's forces. Actually drawing the curved wall and towers was another matter, involving vanishing points literally yards away, much farther than my longest ruler would reach. I'm not sure how appropriate the great many-leggèd caterpillar thing is any more, but I do remember the rivers of fire."

-- JOHN HOWE (official site)

Sources: www.flickr.com/photos/47483731@N00/2568156126 & Tolkien Gateway.

#The Fall of Gondolin#Fall of Gondolin#Fantasy Art#J.R.R. Tolkien#Beleriand#John Howe#The First Age#Balrogs#John Howe Art#Quenta Silmarillion#Dark Fantasy#War of the Jewels#1992#Paintings#The Silmarillion#Silmarillion#Quenta Noldorinwa#Siege of Gondolin#The Siege of Gondolin#Tolkien#1990s#Morgoth#The War of the Jewels#90s#Dragons#Legendarium#JRR Tolkien

1 note

·

View note

Text

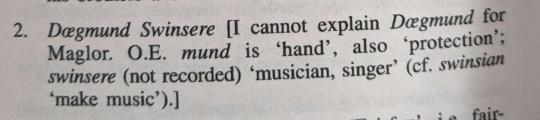

So for those who may not know, Tolkien invented Anglo-Saxon names for the sons of Fëanor (and the Valar and various place names) for an Anglo-Saxon translation of the Quenta Noldorinwa (the beginning of which he actually wrote). This is all in HoMe IV: The Shaping of Middle-earth.

Now, I hear your "I cannot explain", Christopher Tolkien, and as someone utterly ignorant of Anglo-Saxon, I should refrain... but as someone who is unhinged about these characters and their relationship, I must.

Dœgred Winsterhand, the 'left handed'. The one who lost his hand. And his brother, Dœgmund, with the same initial element to his name, plus a word meaning hand. That also means protector. Dœgmund, the hand of Dœgred, his protector, beside him until the end.

These two...🥹😭

#maedhros#maglor#quotes#the history of middle-earth#yes you have my blessing to turn this into a maemags post if you so desire

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s interesting how many of the mothers in Tolkien are so ... sad? I’m calling them the Sad Mums Club. There are others I could have potentially included in this list, but I chose these seven because their sadness is explicitly tied in some way to their children, whether it be exhaustion from birth, fear for their children, giving birth alone after the loss of a partner, or something else. I’m not entirely sure what to make of these parallels, but I do find them interesting.

Miriel - “In the bearing of her son Miriel was consumed in spirit and body; and after his birth she yearned for release from the labour of living.” - The Silmarillion.

Elwing - “for Elwing seeing that all was lost and her children Elros and Elrond taken captive, eluded the host of Maidros, and with the Nauglafring upon her breast she cast herself into the sea.” - Quenta Noldorinwa.

Idril - “Idril fell into a dark mood, and the light in her face was clouded, and many wondered thereat [...] she said to him how her heart misgave her for fear concerning Earendel their son, and for boding that some great evil was nigh.” - The Fall of Gondolin.

Gilraen - “Ónen i-Estel Edain, ú-chebin estel anim” - meaning “I gave hope to the Dunedain, I have kept none for myself.” - LOTR Appendices.

Mithrellas - “But when she had borne [Imrazor] a son, Galador, and a daughter, Gilmith, she slipped away by night and he saw her no more.” - Unfinished Tales.

Morwen - “Morwen gave birth to her child, and she named her Nienor, which is Mourning.” - The Children of Hurin.

Rian - “When her child Tuor was born [the Grey Elves of Mithrim] fostered him. But Rian went to the Haudh-en-Nirnaeth, and laid herself down there, and died.” - The Children of Hurin.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

The evolution of the Oath of Fëanor

I was interested in comparing the different versions of the Oath of Fëanor to understand the similarities and differences and how it changed over time. So I went through HoMe and copied all the different versions to look at them side by side.

To start with, the earliest mention of the Oath appears in The Book of Lost Tales, and it was sworn by Fëanor’s sons, but not Fëanor himself, after the Noldor came to Beleriand:

Then the Seven Sons of Fëanor swore an oath of enmity for ever against any that should hold the Silmarils. / The Seven Sons of Fëanor swore their terrible oath of hatred for ever against all, Gods or Elves or Men, who should hold the Silmarils...

The next version appears in the Flight of the Noldoli from The Lays of Beleriand; Fëanor himself now initiates the Oath and swears it in Valinor. This is also the earliest version of the actual words of the Oath:

‘I swear here oaths, unbreakable bonds to bind me ever,

by Timbrenting and the timeless halls

of Bredhil the Blessed that abides thereon—

may she hear and heed—to hunt endlessly

unwearying unwavering through world and sea,

through leaguered lands, lonely mountains,

over fens and forest and the fearful snows,

till I find those fair ones, where the fate is hid

of the folk of Elfland and their fortune locked,

where alone now lies the light divine.’

Then his sons beside him, the seven kinsmen,

crafty Curufin, Celegorm the fair,

Damrod and Diriel and dark Cranthir,

Maglor the mighty, and Maidros tall

(the eldest, whose ardour yet more eager burnt

than his father's flame, than Fëanor’s wrath;

him fate awaited with fell purpose),

these leapt with laughter their lord beside,

with linked hands there lightly took

the oath unbreakable; blood thereafter

it spilled like a sea and spent the swords

of endless armies, nor hath ended yet:

‘Be he friend or foe or foul offspring

of Morgoth Bauglir, be he mortal dark

that in after days on earth shall dwell,

shall no law nor love nor league of Gods,

no might nor mercy, not moveless fate,

defend him for ever from the fierce vengeance

of the sons of Fëanor, whoso seize or steal

or finding keep the fair enchanted

globes of crystal whose glory dies not,

the Silmarils. We have sworn for ever!’

The next version appears in The Lay of Leithian, The Lays of Beleriand:

They joined in vows, those kinsmen seven,

swearing beneath the stars of Heaven,

by Varda the Holy that them wrought

and bore them each with radiance fraught

and set them in the deeps to flame.

Timbrenting's holy height they name,

whereon are built the timeless halls

of Manwë Lord of Gods. Who calls

these names in witness may not break

his oath, though earth and heaven shake.

Curufin, Celegorm the fair,

Damrod and Diriel were there,

and Cranthir dark, and Maidros tall

(whom after torment should befall),

and Maglor the mighty who like the sea

with deep voice sings yet mournfully.

‘Be he friend or foe, or seed defiled

of Morgoth Bauglir, or mortal child

that in after days on earth shall dwell,

no law, nor love, nor league of hell,

not might of Gods, not moveless fate

shall him defend from wrath and hate

of Fëanor's sons, who takes or steals

or finding keeps the Silmarils,

the thrice-enchanted globes of light

that shine until the final night.’

This is followed by another version of the Oath which appears in Sketch of the Mythology from The Shaping of Middle-earth, after Tolkien stopped working on the poetic Silmarillion and turned to the prose version:

Fëanor and his sons take the unbreakable oath by Timbrenting and the names of Manwë and Bridil to pursue anyone, Elf, Mortal, or Orc, who holds the Silmarils.

The next version appears in the Quenta Noldorinwa from The Shaping of Middle-earth:

Then he swore a terrible oath. His seven sons leaped straightway to his side and took the selfsame vow together, each with drawn sword. They swore an oath which none shall break, and none should take, by the name of the Allfather, calling the Everlasting Dark upon them, if they kept it not; and Manwë they named in witness, and Varda, and the Holy Mount, vowing to pursue with vengeance and hatred to the ends of the world Vala, Demon, Elf, or Man as yet unborn, or any creature great or small, good or evil, that time should bring forth unto the end of days, whoso should hold or take or keep a Silmaril from their possession.

And this is the version of the Oath in the Annals of Aman from Morgoth’s Ring:

Then Fëanor swore a terrible oath. Straightway his seven sons leaped to his side and each took the selfsame oath; and red as blood shone their drawn swords in the glare of the torches.

‘Be he foe or friend, be he foul or clean,

brood of Morgoth or bright Vala,

Elda or Maia or Aftercomer,

Man yet unborn upon Middle-earth,

neither law, nor love, nor league of swords,

dread nor danger, not Doom itself,

shall defend him from Fëanor, and Fëanor’s kin,

whoso hideth or hoardeth, or in hand taketh,

finding keepeth or afar casteth

a Silmaril. This swear we all:

death we will deal him ere Day’s ending,

woe unto world’s end! Our word hear thou,

Eru Allfather! To the everlasting

Darkness doom us if our deed faileth.

On the holy mountain hear in witness

and our vow remember, Manwë and Varda!’

Thus spoke Maidros and Maglor, and Celegorn, Curufin and Cranthir, Damrod and Diriel, princes of the Noldor. But by that name none should swear an oath, good or evil, nor in anger call upon such witness, and many quailed to hear the fell words. For so sworn, good or evil, an oath may not be broken, and it shall pursue oathkeeper or oathbreaker to the world's end.

And then this is the version of the Oath in The Silmarillion:

Then Fëanor swore a terrible oath. His seven sons leapt straightway to his side and took the selfsame vow together, and red as blood shone their drawn swords in the glare of the torches. They swore an oath which none shall break, and none should take, by the name even of Ilúvatar, calling the Everlasting Dark upon them if they kept it not; and Manwë they named in witness, and Varda, and the hallowed mountain of Taniquetil, vowing to pursue with vengeance and hatred to the ends of the World Vala, Demon, Elf or Man as yet unborn, or any creature, great or small, good or evil, that time should bring forth unto the end of days, whoso should hold or take or keep a Silmaril from their possession. Thus spoke Maedhros and Maglor and Celegorm, Curufin and Caranthir, Amrod and Amras, princes of the Noldor; and many quailed to hear the dread words. For so sworn, good or evil, an oath may not be broken, and it shall pursue oathkeeper and oathbreaker to the world’s end.

—

It’s so interesting to see the Oath of Fëanor take shape!

First of all, it’s interesting that the Oath was originally sworn by Fëanor’s sons, not Fëanor himself. The greater role of the sons in earlier versions of the story can also be seen in the line about Maedhros, ‘whose ardour yet more eager burnt...’

There are many similarities between the poetic versions, even down to specific phrases: ‘friend or foe’ to ‘foe or friend’; ‘foul offspring’ to ‘foul or clean’; ‘no law, nor love’ to ‘neither law, nor love’; ‘not moveless fate’ to ‘not Doom itself’, and so on. ‘League of Gods’ becomes ‘league of hell’ and then ‘league of swords’.

In the earlier versions, Morgoth could still have ‘offspring’—the idea that the Valar could have children was to be discarded as time went on. Theoretically, ‘brood of Morgoth’ in the version in Morgoth’s Ring could also mean offspring, but it probably pertains to creatures that Morgoth did not directly create, but that he had a hand in making, such as the Orcs.

(Only the version from Sketch of the Mythology explicitly mentions Orcs, but it stands to reason that they should generally be omitted, because Fëanor would not have known of them while he was still in Valinor.)

All versions of the Oath threaten violence against those who take or keep a Silmaril, but the version from Morgoth’s Ring introduces ‘whoso hideth or hoardeth...or afar casteth’. And whereas the earlier versions threaten ‘enmity’, ‘hatred’, ‘fierce vengeance’, and ‘wrath and hate’, the version from Morgoth’s Ring explicitly threatens death.

The naming of Taniquetil appears in all the versions after The Flight of the Noldoli. The naming of Varda in witness appears first in The Flight of the Noldoli; then in Sketch of the Mythology both Varda and Manwë are named, and this was clearly to become a central feature of the Oath.

The naming of the Allfather first appears in the version from the Quenta Noldorinwa, and again in Morgoth’s Ring, and this was also to become a central feature of the Oath. In the version in The Silmarillion, it is emphasized even further: ‘by the name even of Ilúvatar’.

The Quenta Noldorinwa also introduces the pivotal element of the Everlasting Darkness, which had not been mentioned up until that point, but would obviously persist into later versions.

The element of the drawn swords also first appears in the Quenta Noldorinwa, and their swords shine ‘red as blood’ in Morgoth’s Ring in language that is identical to the passage in The Silmarillion. The phrasing ‘which none shall break, and none should take’ is also identical to The Silmarillion.

It’s also interesting that the version in The Book of Lost Tales says the sons of Fëanor swore an oath of hatred against ‘Gods or Elves or Men’, but then the versions from The Lays of Beleriand do not mention the Oath being directed against the Gods, but this element returns in the Quenta Noldorinwa and persists to Morgoth’s Ring (which adds Maiar to the list) and The Silmarillion.

Overall, as the Oath of Fëanor evolved, it seems that it became much more dangerous and malicious and took on ever greater significance in the story. It was never not dangerous, but the Fëanorians kept adding to their list of enemies until they were threatening to pursue to the end of the world any creature, good or evil, who should possess a Silmaril. The imagery of the drawn swords shining red as blood, which appears in the later versions of the Oath, emphasizes the intent behind it.

And although the Oath was already called ‘unbreakable’ in The Flight of the Noldoli, in later versions the sense of its finality and binding nature is much stronger because of the naming of the Valar, the naming of Ilúvatar, and invoking the Everlasting Darkness.

I made this chart to show the evolution of the Oath over time:

Also, Morgoth’s Ring introduces the sentence, ‘For so sworn, good or evil, an oath may not be broken, and it shall pursue oathkeeper or oathbreaker to the world's end.’ This raises an interesting problem: if an oath cannot be broken, then there can’t be oathbreakers. But it says such an oath may not be broken; clearly it is possible to break. (This is backed up by the fact that, in some versions of the story, Maedhros foreswore the Oath. That isn’t the outcome Tolkien ended up choosing—but it shows that it was possible.)

On a final note, it’s also interesting that the Fëanorians threaten to pursue ‘to the ends of the World Vala, Demon, Elf or Man...’ and then it says such an oath ‘shall pursue oathkeeper and oathbreaker to the world’s end.’ I think that’s it. The Fëanorians swore an oath to pursue their enemies with vengeance—but the oath turned on them instead.

#Tolkien#HoMe#Silmarillion#Oath of Feanor#my writing#because I am INSANE... I literally did a word search in HoMe (I have a PDF of it) and there are over 300 iterations of ''oath''#some of them appear inside other words such as loath or loathsome#so I went through and found all the mentions of the Oath of Feanor#there are many more mentions of it than these seven versions#this was really just an analysis of the content of the oath as it evolved#I stayed up to 5am writing this

355 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@gondolinweek day six | tuor and voronwë

Now Tuor learnt many things in those realms taught by Voronwë whom he loved, and who loved him exceeding greatly in return...

—The Fall of Gondolin, “The Original Tale”

‘I come with Voronwë son of Aranwë, because he was appointed to be my guide by the Lord of Waters. To this end was he delivered from the wrath of the Sea and the Doom of the Valar. For I bear from Ulmo an errand to the son of Fingolfin, and to him will I speak it.’

—The Fall of Gondolin, “The Story Told in the Quenta Noldorinwa”

[Image description: A moodboard of 8 overlapping images. Overlaid is typewriter-style text on little strips of paper reading “Voronwë whom he loved.” Image 1: Headshot of a Solomon Islands man with dark skin, brown eyes, and curly blond hair. 2: An axe from the Solomon Islands. 3: Several Solomon Islanders sailing a tepukei ship. 4: Close-up photo of Ilka Bruhl, a German model with unique facial features, surrounded by wildflowers. 5: Close-up of the decorative handle of another Solomon Islands axe. 6: Foamy seaside waters. 7: A white Solomons cockatoo sitting on brown earth. 8: Pale legs lying partly on sand and partly in the shallows of the ocean. End image description.]

#gondolinweek#gondolinweek2023#tolkienedit#oneringnet#mepoc#tuor#tuor eladar#voronwe#silm#silmarillion#tfog#gondolin#my edit#tefain nin#model: ilka bruhl#i did a melanesian earendil earlier this week so i wanted to do a melanesian tuor to match :)#and i learned a bit about the solomon islands! which was fun!#also yes the cockatoo is a substitute for the swan lol#theyre both white birds!#also i love that quote#they love each other!!!!#voronwe + tuor qpr <333

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Any Maedhros headcanons?

So many that I wasn't sure where to even begin!

In general my headcanons tend to be very flexible. I like exploring different possibilities, so nothing's really fixed in my head. But I do tend to be relatively constant with things like characterisation, and there's certainly some headcanons that are more set than others.

I've written before about Maedhros's feelings on his amputation and prosthetics. I also believe in some of the common headcanons/fanons out there, like the idea that the Oath was a real tangible curse or the idea that Maedhros really believed and hoped that he was going to the Everlasting Dark at the end.

I have two other Maedhros headcanons that I’m particularly fond of, but I’ll put the second one under the cut for length.

.

1. Elrond and Maedhros were very close; closer than Elrond and Maglor or Elros and Maedhros.

My headcanon here is influenced by three things.

First, given the complicated circumstances, I think their relationship is utterly fascinating. So is the relationship between the twins and Maglor of course, but there's something even more compelling about the relationship with Maedhros because of his role as the leader of the Sons of Feanor.

Secondly, it's definitely influenced by this quote from the first draft of the Quenta Noldorinwa;

But Maidros took pity upon her child Elrond, and took him with him, and harboured and nurtured him, for his heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath.

At this stage in Tolkien's construction of the First Age, Elros doesn't exist. It's only in the final draft that Elros comes into being and Maglor switches roles with Maedhros here. But I love the idea of Elrond and Maedhros having a special bond. I love the idea that Elrond's first introduction to scholarship was being learning all the knowledge of Feanor and history of the Noldor at Maedhros's knee.

Thirdly, they're my two favourite characters in the whole legendarium and I just want them to care about each other, dammit.

.

2. Maedhros's emotional support cat

During Maedhros's recovery, young Celebrimbor comes thudding into the tent one day like, dad!!! look!!! look what i found!!! and carrying a hideous, filthy, huge mass of fur. It’s one of the ugliest and grumpiest creatures you’ve ever seen. The healers want it out immediately because it's a massive infection risk. Curufin wants it out immediately because he thinks it's a demonic entity.

The cat hisses at Maedhros. Maedhros hisses right back. And thus a fast friendship is formed, to literally everyone’s dismay.

Maedhros is the ONLY person the cat will tolerate. The healers hate it until they realise that it actually calms Maedhros down, and they can even undo Maedhros's bandages without him fighting them if he has the cat there to calm him. (He still shakes the entire time and his fingers are white where they're gripping the cat's fur, but it’s progress.)

Maedhros also a) craves touch more than anything, he's so touch starved, please b) absolutely cannot stand to be touched. Every touch makes his skin crawl. Everything takes him back there.

But the cat is... fine.

It’s the one thing that is untainted by memories of Angband. It doesn’t give him flashbacks, it has no hidden ulterior motives. He knows it's not Sauron in disguise because, frankly, Sauron would never craft a form this ugly.

Being able to simply touch another being again is a godsend. It’s a huge step, and it starts him on the long slow road back to recovery.

The cat is also a great aid for the nightmares. Does it cuddle him? No. It sleeps on his chest, and if he starts making noises/ twitching in his sleep it gets annoyed and whacks him across the face until he wakes up. Also, it hates everyone except Maedhros, so if someone walks into the tent it hisses (or yowls, depending on whether it recognises the person) and digs its claws into Maedhros's chest. This may seem like an inconvenience, but it's actually the best thing that Maedhros could have ever asked for because he's terrified of someone coming in while he's asleep.

It stays with Maedhros as he gets better and recovers. Somebody eventually manages to establish that the cat is a she, and Maedhros names her Uvanime. Uvanime is the feminine version of the Quenya Uvanimo, meaning monster, a corrupt or hideous creature. Uvane means ugly.

She goes to Himring with him. She's a shoulder cat and likes to lie around Maedhros's neck like a scarf. People think that he's wearing a fur collar until the collar looks up and hisses at them.

When she dies, Maedhros cremates her and scatters her ashes from the highest tower in Himring. The wind is a southerly. It blows the ashes towards Angband.

Maedhros has a few other cats in his life, but none are personally his, and he's never as emotionally involved as he was with Uvane.

#maedhros#elrond#silmarillion#headcanons#quiet rambles#maedhros's emotional support cat#post thangorodrim

66 notes

·

View notes

Note

What's your opinion on Elwing and her abandonment of Elrond and Elros? Personally, I have a hard time sympathizing with her leaving her children.

I talked about this in a reblog of @martaaa1506 ‘s post. Now, though, I have a few additions to make, so I’ll include those along with quoting my words on the reblog:

[Quote]

“I definitely feel that Elwing part. What’s always bothered me so much about people shaming Elwing for “leaving her children to die” and not searching for them or holding on to hope that they might be spared is that it completely ignores the treatment Elwing has endured from the Fëanorians. Her entire family was killed by them - her older brothers, her mother, her father - not to mention her entire kingdom was brought down, and she was really quite young when this happened too. I can’t even begin to imagine the trauma she must have endured because of the Fëanorians, nor do I want to.”

[Addition #1]

This is a passage from the Quenta Noldorinwa detailing the Third Kinslaying:

And yet Maedhros gained not the Silmaril, for Elwing seeing that all was lost and her child[ren] Elrond [and Elros] taken captive, eluded the host of Maedhros, and with the Nauglamír upon her breast she cast herself into the sea and perished, as folk thought.

As stated explicitly in this particular passage, Elrond and Elros were taken captive by the Fëanorians. It is Elwing’s decision after she learns this that has led to her being quite heavily shamed in the Tolkien fandom: her decision to throw herself into the sea and, by extension, her decision to prioritize keeping the Fëanorians from obtaining the Silmaril over staying with her sons; many people argue that as a mother, she should have held on to hope that they might be spared and so stayed with them. And for this, I want to ask (back to quoting myself):

[Quote Cont.]

“If a band of people succeeded in slaying your entire family and bringing your kingdom - one of the few kingdoms that endured against Morgoth - down, why would you have any reason to believe that your sons were spared? The Fëanorians literally took everything from Elwing, and the only image of themselves that they showed her is that of being complete monsters, willing to invade a kingdom, kill people who did absolutely no wrong to them, and even attack a refugee camp. Not a kingdom with a military, guys. A fucking refugee camp, where people who have lost their homes are just trying to cope with their grief and survive - and the Fëanorians brutally attacked and slaughtered them. Why in the world would Elwing believe there was any chance that her sons were left alive? Why would she believe there was any possibility that the Fëanorians would be merciful? If we consider what Elwing has gone through, it’s not hard to rationalize that she views the Fëanorians as utter demons. And from her perspective? She has every right to totally loathe them.

It wasn’t right of Elwing to leave her sons; I’m not denying that. But I really, really feel that most of the fandom takes too little consideration of just how much revulsion and horror Elwing must feel towards the Fëanorians.”

[Addition #2]

It frustrates me how little empathy Elwing is shown in her situation. From her perspective, after all the sorrow and horror the Fëanorians have caused her, she had two choices: (1) Stay with her soon-to-be-dead, if not already dead, sons, and lose the Silmaril that her parents died trying to keep away from the sons ofFëanor to the sons of Fëanor, rendering her entire family’s death pointless. (2) Leave her soon-to-be-dead, if not already dead, sons, but keep the Silmaril that her parents died trying to keepaway from the sons of Fëanor away from the sons of Fëanor, ensuring that her entire family’s death was not pointless.

And I suppose a perfect mother, one who prioritizes being able to stay with her (in her mind, as good as dead) children above anything and everything else, would have made a different choice. Elwing didn’t, and she’s harshly criticized and even heavily disliked as a result, and that’s something I frankly find rankling, especially because the responsibility of theFëanorians in creating Elwing’s trauma against them, as well as Elwing’s intense trauma in general, goes virtually unnoticed and uncommented on. I’ve seen very few people even take it into consideration. Like, come on. I understand that these situations are complex and open to a variety of opinions, but I really wish there wasn’t quite so much severe disparaging of Elwing and her competence as a mother because of her decision, without even thinking of her perspective.

#elwing#tolkien#tolkien meta#tolkien quotes#the fall of gondolin#quenta noldorinwa#the fall of gondolin quotes#house of fëanor#sons of fëanor#elrond#elros#havens of sirion#the third kinslaying

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

tolkien seems to admit that that evil exists but never as something independent. rather as smth that always returns to good. however he doesn't seem to admit that it can be an inherent part of the process to reach good. it's always, somehow, also other and never a part of eru. the silm says that melkor develops "thoughts of his own" while wandering in search of the imperishable flame, but that of course cannot be, as he is made of eru's thoughts. and yet never OF eru, but simply eru's instrument. as though necessarily existing, but excised.

#this should just go in the thesis#however it's simpler to post online without citations#quenta noldorinwa

111 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there any canon evidence that Finrod and Maglor were friends during the Age of The Trees in Valinor?

Thank u for your time 7:3

None!

The only canonical interaction between these two singers is their hunting trip (with Maedhros, too). As told in Of the Coming of Men into the West:

When three hundred years and more were gone since the Noldor came to Beleriand, in the days of the Long Peace, Finrod Felagund lord of Nargothrond journeyed east of Sirion and went hunting with Maglor and Maedhros, sons of Fëanor.

Fun fact: in an earlier Silmarillion draft, Finrod went hunting with Celegorm instead of these two (History of Middle-earth, Vol. IV: The Shaping of Middle-earth, Quenta Noldorinwa §9).

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

More fun quotes from the Beren and Luthien novel, this time from Tolkien's drafts of Quenta Noldorinwa:

"Then Luthien dared the most dreadful and most valiant deed that any of the Elves have ever dared; no less than the challenge of Fingolfin is it accounted, and may be greater, save that she was half-divine."

Love how Tolkien here explicitly calls out the courage it took for Luthien to reveal herself to Melkor and take him on, and sets her right beside Fingolfin in terms of bravery.

"And she beguiled Morgoth...what song can sing the marvel of that deed, or the wrath and humiliation of Morgoth, for even the Orcs laugh in secret when they remember it, telling how Morgoth fell from his chair and his iron crown rolled upon the floor."

Even Melkor is not immune to being laughed at by his henchmen.

"But he [Daeron] came never back to Doriath and strayed into the East of the world."

There's just so much fannish potential here. Ranking Daeron as most likely First Age Elf cryptid. Hope he found some nice waterfalls in the east.

"Boldog the captain of the Orcs was there slain in battle by Thingol, and his great warriors Beleg the Bowman and Mablung Heavyhand were with Thingol in that battle."

We love a good battle king, especially given how much Melkor has it out for Doriath.

"And Mandos suffered them to depart, but he said that Luthien should become mortal even as her lover, and should leave the earth once more in the manner of mortal women, and her beauty become but a memory of song."

I know there's fandom debate as to whether Luthien visibly aged as mortals do after being given this fate, and I'm taking that end part of the sentence as evidence that she did. Luthien chose a mortal fate--which means she chose throwing out her back and getting wrinkles and gray hair and losing her eyesight too. And she was still full of joy, and Beren still loved her and thought her the most beautiful person in the world, and she still did not regret her choice.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Third Kinslaying

A Silmarillion question that never ceases to trouble me, and for which I am not sure I will ever come up with an answer that satisfies me: What were Maedhros and Maglor’s justifications for taking Elrond and Elros after the sack of Sirion?

I know many people are satisfied with emotion-based reasoning, but that alone just doesn’t work for me personally. I read Maedhros and Maglor at this point in the narrative as very tormented, yes, but still capable of weighing logic and emotion at the same time. I also don't think the tone of the text supports outright villainy and ruthlessness (though that's a valid hc, especially from a non-Feanorian pov).

I’m not going to dive into my interpretation (I’m writing a fic for that), but I wanted to share the evidence and highlight what I think is the (Doylist) explanation for why the question is such a tough one to crack: None of Tolkien’s drafts covering this event* took the character of Gil-galad (or Círdan, though he was a character and not ret con'd like G-g) into consideration. He was simply not a factor in any of the versions published in HoMe.

If you’re like me and love the ‘textual archaeology’ of figuring out how the published text was derived (and since I bothered to type them all up) here are all the drafts of the third kinslaying alongside the published Silm. (There's good stuff in here for enjoyers of Elwing, Maedhros, and Maglor, too -- and haters of Amrod and Amras lol.)

*unless there are unpublished notes or notes that have evaded me somewhere

Book of Lost Tales (late 1910s/early 1920s)

In BoLT, the Havens are sacked by Melko.

Sketch of the Mythology (1926-30)

The sons of Fëanor learning of the dwelling of Elwing and the Nauglafring [=Nauglamir] had come down on the people of Gondolin. In a battle all the sons of Fëanor save Maidros [footnote: > Maidros and Maglor] were slain, but the last folk of Gondolin destroyed or forced to go away and join the people of Maidros [footnote: Written in the margin: Maglor sat and sang by the sea in repentance]. Elwing cast the Nauglafring into the sea and leapt after it [footnote: My father first wrote Elwing cast herself into the sea with the Nauglafring, but changed it to Elwing cast the Nauglafring into the sea and leapt after it in the act of writing], but was changed into a white sea-bird by Ylmir [=Ulmo], and flew to seek Eärendel, seeking about the shores of the world.

Their son (Elrond) who is half-mortal and half-elfin [footnote: This sentence was changed to read: Their son (Elrond) who is part mortal and part elfin and part of the race of the Valar], a child, was saved however by Maidros.”

The Quenta Noldorinwa (1930)

I

The dwelling of Elwing at Sirion’s mouth, where still she possessed the Nauglafring and the glorious SIlmaril, became known to the sons of Fëanor; and they gathered together from their wandering hunting-paths. But the folk of Sirion would not yield that jewel which Beren had won and Lúthien had worn, and for which fair Dior had been slain. And so befell the last and cruellest slaying of Elf by Elf, the third woe achieved by the accursed oath; for the sons of Fëanor came down upon the exiles of Gondolin and the remnant of Doriath, and though some of their folk stood aside and some few rebelled and were slain upon the other part aiding Elwing against their own lords, yet they won the day. Damrod [=Amrod] was slain and Díriel [=Amras], and Maidros and Maglor alone now remained of the Seven; but the last of the folk of Gondolin were destroyed or forced to depart and join them to the people of Maidros. And yet the sons of Fëanor gained not the Silmaril; for Elwing cast the Nauglafring into the sea, whence it shall not return until the End; and she leapt herself into the waves, and took the form of a white sea-bird, and flew away lamenting and seeking for Eärendel about all the shores of the world.

But Maidros took pity upon her child Elrond, and took him with him, and harboured and nurtured him, for his heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath.”

II

Upon the havens of Sirion new woe had fallen. The dwelling of Elwing there, where still she possessed the Nauglafring [footnote: > Nauglamir at both occurrences] and the glorious SIlmaril, became known to the remaining sons of Fëanor, Maidros and Maglor and Damrod and Díriel; and the gathered from their wandering hunting-paths, and messages of friendship and yet stern demand they sent unto Sirion. But Elwing and the folk of Sirion would not yield that jewel which Beren had won and Lúthien had worn, and for which Dior the Fair was slain; and least of all while Eärendel their lord was in the sea, for them seemed that in that jewel lay the gift of bliss and healing that had come upon their houses and their ships.

And so came in the end to pass the last and cruellest of the slayings of Elf by Elf; and that was the third of the great wrongs achieved by the accursed oath. For the sons of Fëanor came down upon the exiles of Gondolin and the remnant of Doriath and destroyed them. Though some of their folk stood aside, and some few rebelled and were slain upon the other part aiding Elwing against their own lords (for such was the sorrow and confusion in the hearts of Elfinesse in those days), yet Maidros and Maglor won the day. Alone they now remained of the sons of Fëanor, for in that battle Damrod and Díriel were slain; but the folk of Sirion perished of fled away, or departed of need to join the people of Maidros, who claimed now the lordship of all the Elves of the Outer Lands. And yet Maidros gained not the Silmaril, for Elwing seeing that all was lost and her child Elrond [footnote: > her children Elros and Elrond] taken captive, eluded the host of Maidros, and with the Nauglafring upon her breast she cast herself into the sea, and perished as folk thought.

[...] But great was the sorrow of Eärendel and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons, for whom they feared death, and yet it was not so. For Maidros took pity upon Elrond, and he cherished him, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maidros’ heart was sick and weary [footnote: This passage was rewritten thus: But great was the sorrow of Eärendel and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons; and they feared that they would be slain. But it was not so. For Maglor took pity upon Elros and Elrond, and he cherished them, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maglor’s heart was sick and weary &c.] with the burden of the dreadful oath.

Earliest Annals of Beleriand (AB 1) (1930-37, prior to AB 2)

AB I

225 Torment of Maidros and his brothers because of their oath. Damrod and Díriel resolve to win the Silmaril if Eärendel will not yield it up.

[...]

The folk of Sirion refused to give up the Silmaril in Eärendel’s absence, and they thought their joy and prosperity came of it.

229 Here Damrod and Díriel ravaged Sirion, and were slain. Maidros and Maglor gave reluctant aid. Sirion’s folk were slain or taken into the company of Maidros. Elrond was taken to nurture by Maglor. Elwing cast herself into the sea, but by Ulmo’s aid in the shape of a bird flew to Eärendel and found him returning.

AB II does not go this far.

The Later Annals of Beleriand (AB 2) (1930-37, after AB 1)

325 [525] Torment fell upon Maidros and his brethren, because of their unfulfilled oath. Damrod and Díriel resolved to win the Silmaril, if Eärendel would not give it up willingly. [...] The folk of Sirion refused to surrender the Silmaril, both because Eärendel was not there, and because they thought their bliss and prosperity came from the possession of the gem.

329 [529] Here Damrod and Díriel ravaged Sirion, and were slain. Maidros and Maglor were there, but they were sick at heart. This was the third kinslaying. The folk of Sirion were taken into the people of Maidros, such as yet remained; and Elrond was taken to nurture by Maglor. But Elwing cast herself with the Silmaril into the sea, and Ulmo bore her up, and in the shape of a bird she flew seeking Eärendel, and found him returning.

Quenta Silmarillion (1937) and The Later Quenta Silmarillion (1950s). These drafts were left incomplete and do not cover the events of the third kinslaying.

The Tale of Years (1950s)

Texts A, B

529 Third and Last Kin-slaying

Text C

532 [> 534 > 538] The Third and Last Kinslaying. The Havens of Sirion destroyed and Elros and Elrond sons of Eärendel taken captive, but are fostered with care by Maidros.

Text D2 (ends at 527)

512 Sons of Fëanor learn of the uprising of the New Havens, and that the Silmaril is there, but Maidros forswears his oath.

[...]

527 Torment fell upon Maidros and his brethren (Maglor, Damrod and Díriel) because of their unfulfilled oath.

Letter 211 (1958)

Elrond, Elros. *rondō was a prim[itive] Elvish word for 'cavern'. Cf. Nargothrond (fortified cavern by the R. Narog), Aglarond, etc. *rossē meant 'dew, spray (of fall or fountain)'. Elrond and Elros, children of Eärendil (sea-lover) and Elwing (Elf-foam), were so called, because they were carried off by the sons of Fëanor, in the last act of the feud between the high-elven houses of the Noldorin princes concerning the Silmarils; the Silmaril rescued from Morgoth by Beren and Lúthien, and given to King Thingol Lúthien's father, had descended to Elwing dtr. of Dior, son of Lúthien. The infants were not slain, but left like 'babes in the wood', in a cave with a fall of water over the entrance. There they were found: Elrond within the cave, and Elros dabbling in the water.

The Silmarillion

Now when first the tidings came to Maedhros that Elwing yet lived, and dwelt in possession of the Silmaril by the mouths of Sirion, he repenting of the deeds in Doriath withheld his hand. But in time the knowledge of their oath unfulfilled returned to torment him and his brothers, and gathering from their wandering hunting-paths they sent messages to the Havens of friendship and yet of stern demand. Then Elwing and the people of Sirion would not yield the jewel which Beren had won and Luthien had worn, and for which Dior the fair was slain; and least of all while Earendil their lord was on the sea, for it seemed to them that in the Silmaril lay the healing and the blessing that had come upon their houses and their ships. And so there came to pass the last and cruellest of the slayings of Elf by Elf; and that was the third of the great wrongs achieved by the accursed oath.

For the sons of Feanor that yet lived came down suddenly upon the exiles of Gondolin and the remnant of Doriath, and destroyed them. In that battle some of their people stood aside, and some few rebelled and were slain upon the other part aiding Elwing against their own lords (for such was the sorrow and confusion in the hearts of the Eldar in those days); but Maedhros and Maglor won the day, though they alone remained thereafter of the sons of Feanor, for both Amrod and Amras were slain. Too late the ships of Cirdan and Gil-galad the High King came hasting to the aid of the Elves of Sirion; and Elwing was gone, and her sons. Then such few of that people as did not perish in the assault joined themselves to Gil-galad, and went with him to Balar; and they told that Elros and Elrond were taken captive, but Elwing with the Silmaril upon her breast had cast herself into the sea.

Thus Maedhros and Maglor gained not the jewel; but it was not lost. For Ulmo bore up Elwing out of the waves, and he gave her the likeness of a great white bird, and upon her breast there shone as a star the Silmaril, as she flew over the water to seek Earendil her beloved. [...]

Great was the sorrow of Earendil and Elwing for the ruin of the havens of Sirion, and the captivity of their sons, and they feared that they would be slain; but it was not so. For Maglor took pity upon Elros and Elrond, and he cherished them, and love grew after between them, as little might be thought; but Maglor’s heart was sick and weary with the burden of the dreadful oath.

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

[In J.R.R. Tolkien’s poem] the sibyl declares that the fate of the world and the outcome of the Last Battle will depend on the presence of ‘one deathless who death hath tasted and dies no more’; and this is Sigurd, ‘the serpent-slayer, seed of Ódin’, who is ‘the World’s chosen’ for whom the mailclad warriors wait in Valhöll. As is made explicit in [Tolkien’s] interpretative note [...] it is Ódin’s hope that Sigurd will on the Last Day become the slayer of the greatest serpent of all, Miðgarðsormr, and that through Sigurd ‘a new world will be made possible’.

‘This motive of the special function of Sigurd is an invention of the present poet’, my father observed in the same brief text. An association with his own mythology seems to me at least extremely probable: in that Túrin Turambar, slayer of the great dragon Glaurung, was also reserved for a special destiny, for at the Last Battle he would himself strike down Morgoth, the Dark Lord, with his black sword. This mysterious conception appeared in the old Tale of Turambar (1919 or earlier), and reappeared as a prophecy in the Silmarillion texts of the 1930s: so in the Quenta Noldorinwa, ‘it shall be the black sword of Túrin that deals unto Melko [Morgoth] his death and final end; and so shall the children of Húrin and all Men be avenged.’ Very remarkably a form of this conception is found in a brief essay of my father’s from near the end of his life, in which he wrote that Andreth the Wise-woman of the House of Bëor had prophesied that ‘Túrin in the Last Battle should return from the Dead, and before he left the Circles of the World for ever should challenge the Great Dragon of Morgoth, Ancalagon the Black, and deal him the death-stroke.’ The extraordinary transformation of Túrin is seen also in an entry in The Annals of Aman, where it is said that the great constellation of Menelmakar, the Swordsman of the Sky (Orion), ‘was a sign of Túrin Turambar, who should come into the world, and a foreshadowing of the Last Battle that shall be at the end of Days.’*

#silmarillion#the legend of sigurd and gudrún#tolkien#turin turambar#túrin turambar#túrin#the children of húrin#the battle of battles#queue cutie

83 notes

·

View notes