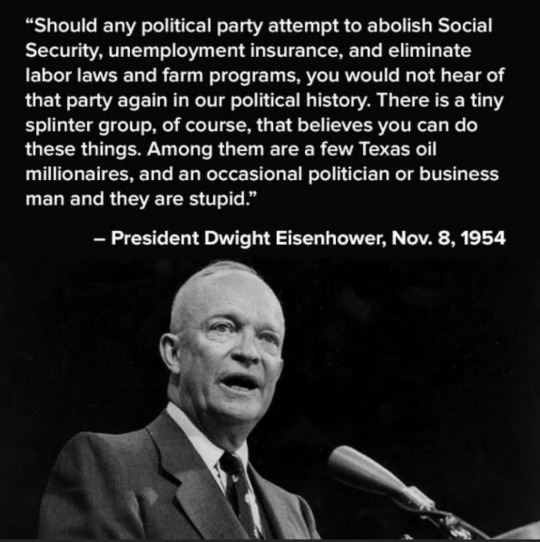

#president eisenhower

Note

Are there any notable Presidential speeches you know of that were fully written or prepared but never delivered for some reason? (Such as Nixon’s failed moon landing speech for Apollo 11)

Off the top of my head, I can't think of any specific speeches similar to the undelivered speech prepared in case of a disaster on Apollo 11 (which is still haunting to read even with the knowledge that everybody made it home safely).

Obviously, most Presidents and Presidential candidates prepare victory and concession speeches, but we don't usually see the speech that wasn't needed. Once some time had passed, Hillary Clinton did read the victory speech that she would have given had she not lost the 2016 election to Trump. It was before he was President, but General Dwight D. Eisenhower had prepared a short statement in 1944 to deliver in case the Allied landings on D-Day had failed.

It's not quite the same thing, but I have a fascinating book called Strictly Personal and Confidential: The Letters That Harry Truman Never Mailed that is a collection of letters and notes that President Truman wrote while angry or annoyed but gave into his better judgment and held back on actually mailing. They are pretty entertaining.

#Speeches#Presidential Speeches#Presidents#History#Presidency#Politics#Undelivered Speeches#Richard Nixon#President Nixon#Apollo 11#Hillary Clinton#2016 Election#Dwight D. Eisenhower#President Eisenhower#D-Day#World War II#Normandy Invasion#General Eisenhower#President Truman#Harry S. Truman#Strictly Personal and Confidential: The Letters That Harry Truman Never Mailed#Presidential Correspondence#Presidential Writing

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

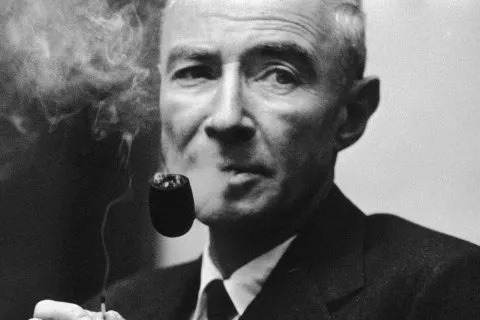

Why Robert Oppenheimer's Atomic Bomb Still Haunts Us

— By Richard Rhodes | Published May 15, 2013

Oppenheimer spearheaded the creation of the atom bomb. René Burri/Magnum

Robert Oppenheimer oversaw the design and construction of the first atomic bombs. The American theoretical physicist wasn't the only one involved—more than 130,000 people contributed their skills to the World War II Manhattan Project, from construction workers to explosives experts to Soviet spies—but his name survives uniquely in popular memory as the names of the other participants fade. British philosopher Ray Monk's lengthy new biography of the man is only the most recent of several to appear, and Oppenheimer wins significant assessment in every history of the Manhattan Project, including my own. Why this one man should have come to stand for the whole huge business, then, is the essential question any biographer must answer.

It's not as if the bomb program were bereft of men of distinction. Gen. Leslie Groves built the Pentagon and thousands of other U.S. military installations before leading the entire Manhattan Project to success in record time. Hans Bethe discovered the sequence of thermonuclear reactions that fire the stars. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi invented the nuclear reactor. John von Neumann conceived the stored-program digital computer. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam co-invented the hydrogen bomb. Luis Alvarez devised a whole new technology for detonating explosives to make the Fat Man bomb work, and later, with his son, Walter, proved that an Earth-impacting asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. The list goes on. What was so special about Oppenheimer?

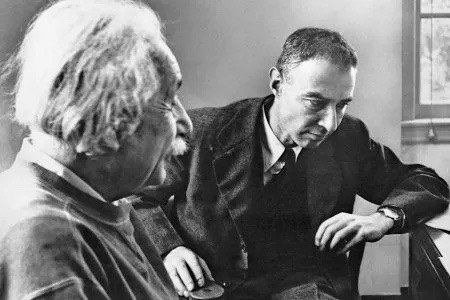

He was brilliant, rich, handsome, charismatic. Women adored him. As a young professor at Berkeley and Caltech in the 1930s, he broke the European monopoly on theoretical physics, contributing significantly to making America a physics powerhouse that continues to win a freight of Nobel Prizes. Despite never having directed any organization before, he led the Los Alamos bomb laboratory with such skill that even his worst enemy, Edward Teller, told me once that Oppenheimer was the best lab director he'd ever known. After the war he led the group of scientists who guided American nuclear policy, the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He finished out his life as director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he welcomed young scientists and scholars into that traditionally aloof club.

August 9, 1945: Nagasaki is hit by an atom bomb. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/EPA

Those were exceptional achievements, but they don't by themselves explain his unique place in nuclear history. For that, add in the dark side. His brilliance came with a casual cruelty, born certainly of insecurity, which lashed out with invective against anyone who said anything he considered stupid; even the brilliant Bethe wasn't exempt. His relationships with the significant women in his life were destructive: his first deep love, Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley professor, was a suicide; his wife, Kitty, a lifelong alcoholic. His daughter committed suicide; his son continues to live an isolated life.

His Choices or Mistakes, Combined with his Penchant for Humiliating Lesser Men, Eventually Destroyed Him.

Oppenheimer's achievements as a theoretical physicist never reached the level his brilliance seemed to promise; the reason, his student and later Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger judged, was that he "very much insisted on displaying that he was on top of everything"—a polite way of saying Oppenheimer was glib. The physicist Isidor Rabi, a Nobel laureate colleague whom Oppenheimer deeply respected, thought he attributed too much mystery to the workings of nature. Monk notes his curiously uncritical respect for the received wisdom of his field.

Monk's discussion of Oppenheimer's work in physics is one of his book's great contributions to the saga, an area of the man's life that previous biographies have neglected. In the late 1920s Oppenheimer first worked out the physics of what came to be called black holes, those collapsing giant stars that pull even light in behind them as they shrink to solar-system or even planetary size. Some have speculated Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel for that work had he lived to see the first black hole identified in 1971.

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein, circa the 1940s. Corbis

Oppenheimer's patriotism should have been evident to even the most obtuse government critic. He gave up his beloved physics, after all, not to mention any vestige of personal privacy, to help make his country invulnerable with atomic bombs. Yet he risked his work and reputation by dabbling in left-wing and communist politics before the war and lying to security officers during the war about a solicitation to espionage he received. His choices or mistakes, combined with his penchant for humiliating lesser men, eventually destroyed him.

One of those lesser men, a vicious piece of work named Lewis Strauss, a former shoe salesman turned Wall Street financier and physicist manqué, was the vehicle of Oppenheimer's destruction. When President Eisenhower appointed Strauss to the chairmanship of the AEC in the summer of 1953, Strauss pieced together a case against Oppenheimer. He was still splenetic from an extended Oppenheimer drubbing delivered during a congressional hearing all the way back in 1948, and he believed the physicist was a Soviet spy.

Strauss proceeded to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance, effectively shutting him out of government. Oppenheimer could have accepted his fate and returned to an academic life filled with honors; he was due to be dropped as an AEC consultant anyway. He chose instead to fight the charges. Strauss found a brutal prosecuting attorney to question the scientist, bugged his communications with his attorney, and stalled giving the attorney the clearances he needed to vet the charges. The transcript of the hearing In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.

Rabi was one of the few witnesses who stood up for his friend, finally challenging the hearing board in exasperation, "We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it [because of Oppenheimer's work], and what more do you want, mermaids?" What Strauss and others, particularly Edward Teller, wanted was Oppenheimer's head on a platter, and they got it. The public humiliation, which he called "my train wreck," destroyed him. Those who knew him best have told me sadly that he was never the same again.

For Monk as for Rabi, Oppenheimer's central problem was his hollow core, his false sense of self, which Rabi with characteristic wit framed as an inability to decide whether he wanted to be president of the Knights of Columbus or B'nai B'rith. The German Jews who were Oppenheimer's 19th-century forebears had worked hard at assimilation—that is, at denying their religious heritage. Oppenheimer's parents submerged that heritage further in New York's ethical-culture movement that salvaged the humanism of Judaism while scrapping the supernatural overburden. Oppenheimer, actor that he was, could fit himself to almost any role, but turned either abject or imperious when threatened. He was a great lab director at Los Alamos because of his intelligence—"He was much smarter than the rest of us," Bethe told me—because of his broad knowledge and culture; because of his psychological insight into the complicated personalities of the gifted men assembled there to work on the bomb; most of all because he decided to play that role, as a patriotic citizen, and played it superbly.

Monk is a levelheaded and congenial guide to Oppenheimer's life, his biography certainly the best that has yet come along. But he devotes far too many pages to Oppenheimer's Depression-era flirtation with communism, a dead letter long ago and one that speaks more of a rich esthete's awakening to the suffering in the world than to Oppenheimer's political convictions. He doesn't always get the science right. Most of the errors are trivial, but a few are important to the story.

Their Fundamental Objection Was to Giving up Production of Real Weapons so That Teller Could Pursue His Pipe Dream, a Dead-end Hydrogen Bomb Design.

A fundamental reason Oppenheimer opposed a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in response to the first Soviet atomic-bomb test in 1949 was the requirement of Edward Teller's "Super" design for large amounts of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium. Tritium is bred by irradiating lithium in a nuclear reactor, but the slugs of lithium take up space that would otherwise be devoted to breeding plutonium. To make tritium for a hydrogen bomb that the U.S. did not know how to build would have required sacrificing most of the U.S. production of plutonium for devastating atomic bombs the U.S. did know how to build. To Oppenheimer and the other scientists on the GAC, such an irresponsible substitution as an answer to the Soviet bomb made no strategic sense. It's true that the hydrogen bomb with its potentially unlimited scale of destruction made no military sense to them either—and was morally repugnant to some of them as well. But their fundamental objection, which Monk overlooks, was to giving up production of real weapons so that Teller could pursue his pipe dream, a dead-end hydrogen bomb design that never worked.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967)

More egregious is Monk's notion that the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, Oppenheimer's mentor during the war on the international implications of the new technology, pushed for the bomb's use on Japan to make its terror manifest. He did not. He pushed, to the contrary, for the Allies, the Soviet Union included, to discuss the implications of the bomb prior to its use and to devise a framework for controlling it. Bohr foresaw that the bomb would stalemate major war, as it has, but correctly feared that U.S. secrecy about its development would lead to a U.S.-Soviet arms race. He conferred with both Roosevelt and Churchill about presenting the fact of the bomb to the Russians as a common danger to the world, like a new epidemic disease, that needed to be quarantined by common agreement. Churchill vehemently disagreed, and Roosevelt was old and ill. The moment passed. The arms race followed, as Bohr foresaw, and with diminished force, among pariah states like Iran and North Korea, continues to this day.

Monk's Oppenheimer is a less appealing figure than the Oppenheimer of previous biographies, perhaps because, as an Englishman, Monk is less susceptible to Oppenheimer's rhetorical gifts and more candid about calling out his evasions. He pulls together most of what several generations of Oppenheimer scholars have found and offers new revelations as well. Yet there's a faint whiff of condescension in his portrait, and the real Oppenheimer, the man whom so many loved and admired, still somehow escapes him. He misses the deep alignment of Robert Oppenheimer's life with Greek tragedy, the charismatic hubris that was his glory but also the flaw that brought him low. But maybe I'm expecting too much: maybe only a large work of fiction could assemble that critical mass.

#Robert Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Richard Rhodes#World War II#Manhattan Project#Ray Monk#Gen. Leslie Groves#Pentagon#Hydrogen Bomb#Edward Teller | Stanislaw Ulam#Nobel Prize#Princeton University#Albert Einstein#President Eisenhower#Lewis Strauss#Hydrogen | Tritium | Plutonium#Roosevelt | Churchill#US — Soviet Union

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco leave the White House on October 11, 1956, following their 30-minute visit with President Eisenhower. They described their meeting with the President as "purely social."

The informal visit was arranged at the request of the Prince. Queried by newsmen about her choice in the forthcoming Presidential election, the Princess said that she will not vote because she is the wife of the head of a foreign state.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Nuclear physicist Ernest Lawrence, portrayed by Josh Hartnett in Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer, continued his ambitious scientific pursuits and advocacy after the events that took place in the film. Once a close friend and associate of theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer on the infamous Manhattan Project, Lawrence became a central figure in the advancement of institutionalized and government-funded support of scientific programs which was eventually referred to as Big Science.

Lawrence and Oppenheimer were close enough throughout their lifetimes that he named one of his sons, Robert, after the father of the atomic bomb. The scientific collaborators met at the prestigious UC Berkeley where Lawrence first expressed his concerns for Oppenheimer's questionable political affiliations and sensibilities. At the end of Oppenheimer, Lawrence withdraws from testifying against his colleague at his security clearance hearing, claiming to have fallen ill due to colitis. This is the last time that Lawrence appears in the film, raising the question of what the physicist did with the rest of his life.

What Ernest Lawrence Did After Oppenheimer's Security Clearance Hearing

After not participating in Oppenheimer's four-week security clearance hearing in 1954, Ernest Lawrence worked closely with President Dwight D. Eisenhower as a representative of government-endorsed scientific and technological advancements. The President requested Lawrence's presence in Geneva, Switzerland in order to help establish a Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty with the Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War, an effort that Oppenheimer himself voiced strong opinions in favor of following the end of World War II. Lawrence was recommended by Lewis Strauss of the AEC to travel to Switzerland with the President with the diplomatic proposal.

Ernest Lawrence Died In 1958

Despite having recurring illnesses from his chronic colitis, which got him out of testifying against Oppenheimer in 1954, Lawrence found the significance of accompanying President Eisenhower and decided to go. During the trip, Lawrence has a serious flare-up that required immediate medical attention. He was flown back to the Palo Alto Hospital at Stanford University where he had much of his large intestine removed in a drastic effort to save his life. The surgeons discovered other complications and troubling signs during the procedure that pointed to atherosclerosis in one of his arteries.

Only a month after leaving for Geneva, Lawrence died on August 27, 1958 at age 57. The University of California at Berkeley renamed two of its nuclear research laboratories after Lawrence. An award was immediately created in his honor to acknowledge the future achievements of other great scientists. Lawrencium, the 103rd known chemical element of the periodic table, was named after him. His portrayal in Oppenheimer by Josh Hartnett reaffirms his legacy and significance in the world of 20th-century physics and the outcome of World War II.'

#Ernest Lawrence#Oppenheimer#Josh Hartnett#Christopher Nolan#President Eisenhower#The Manhattan Project#Lawrencium

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

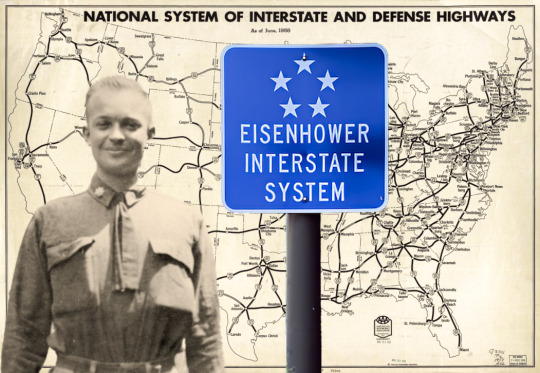

Eisenhower Highway: 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy

The Transcontinental Motor Convoys 1919 was a vehicle convoy of the US Army of truck trains, Harley and Indian motorcycles, passenger cars, and heavy equipment that crossed the United States to the west coast.

The Transcontinental Motor Convoys 1919 was a vehicle convoy of the US Army of truck trains, Harley and Indian motorcycles, passenger cars, and heavy equipment that crossed the United States to the west coast. The 1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy was from Washington, D.C., to San Francisco using the incomplete Lincoln Highway. A young Dwight Eisenhower was one of the officers in charge and it…

youtube

View On WordPress

#A HISTORY SERIES#Absolute History#American History#Eisenhower#freeways#highways#Historical#historical footage#history#history footage#history lesson#history lessons#history teacher#Lincoln highway#president Eisenhower#transportation#us history#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Global Village

We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.

Winston Churchill, 1943

A symbiosis between NASA and the shrinking of the world into a global village informs the provenance of the telecommunications industry. The export of satellite technology from the pages of science fiction into the ether above was first articulated by the polymath Arthur Clark in 1945. Seminal to the industry the white-paper titled ‘Extra-Terrestrial Relays’ conjured up a world not connected by short-wave radio or a lattice of undersea cables but rather by signals bounced off stations in the void of space. A web of these satellites orbiting the earth unfettered by atmospheric disturbances could be a medium for real-time communication. The sheer audacity of this idea cannot be stressed enough. When the monograph was penned humanity had scarcely pierced the boundaries of space with its primitive technology. The highest altitude recorded by a V-2 rocket topped the distance of 189km in suborbital flight (Lee 2020). Just for Clarke’s hypothetical satellite to be entertained it would need to reach the threshold of 36,000km. The grandiosity of this foresight evokes the same futurism gleaned from Leonardo da Vinci’s first doodles on the mechanics of flight centuries ahead of their invention. But rather than be dismissed as a fit of daydreaming in less than two decades were these wild speculations of satellite technology brought to life.

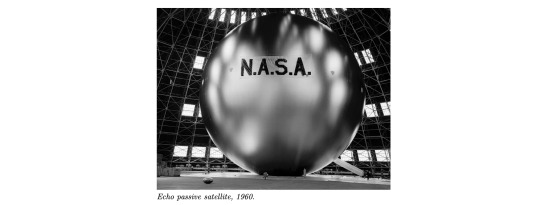

America’s formal dalliance with transmitting signals into the vast unknown began with President Eisenhower’s industrial policy in 1958. Abreast of Projects Mercury, Gemini and Apollo another triptych begot a quantum leap in the separate firmament of global communication during the jet age. Projects Echo, Relay and Syncom each escalating in sophistication came to experiment with bouncing microwave frequencies off passive and active satellites from ground stations below. A diverse consortium of firms brainstormed these instruments under the auspices of NASA. In the halcyon days of adventurism into the cosmos Project Echo became a totem for a proof of concept to test whether radio signals could piggyback on objects in orbit for the sake of long-distance communication. This maiden satellite from 1960 was effectively a monolithic balloon of aluminized Mylar whose reflective properties redirected signals from a laboratory in California to one in New Jersey. Initially the Aeronautics Division of the foodstuff maker General Mills was recruited to build this galactic mirror but when it was discovered that it would fray in the inhospitable vacuum of space the firm was jettisoned for the Schjeldahl company. To stave off premature ruptures of the orb’s skin a single fortified seam was introduced versus the previous patchwork.

Upping the ante in technical specifications for the sequel to Project Echo was the Relay satellite which sought to undo the tyranny of geography. Communication signals via traditional infrastructure were liable to degradation over long distances at a prohibitive cost in capital. By contrast the bandwidth of Project Relay exhibited a fidelity heretofore unseen with the bonus of transmitting across further expanses. Whereas short-wave radio failed to penetrate the vicissitudes of atmospheric conditions whether it be through fog or rain this alternative had no such deficit that may throttle it. Moreover skeptics had to be reminded about the economies of scope whereby television, radio and telephone signals could be diffused on a single piece of hardware rather than across a multitude of terrestrial stations like in legacy systems. No longer would the geometry of communication be at the mercy of oceans or mountains but instead find deliverance in the airwaves far above. Thus the utility of Project Relay was not lost on policymakers whose analysis of the costs and benefits vindicated the industrial policy to finance it. Project Relay legitimized satellites when operational expenditures were bound to plummet as the onus of maintenance was removed. Telecommunications therefore was the very first technology to commercialize space.

A jigsaw of private stakeholders pooled resources together to inaugurate this next chapter in the study of satellite technology. One particular enigma that needed to be demystified promptly was the longevity of Relay’s testbed as its honeycomb of solar cells would face a barrage of cosmic radiation in the Van Allen Belt. The rate of degradation had to be probed and then mitigated if delicate electronics were to weather the wilds of space. Any viability hinged on ensuring a lengthy lifecycle of the satellite in this minefield of hazards and so advanced measuring hardware approximated 11 percent of the weight for the first iteration (Ezell 1988: 376). The omnipresence of radiation had to be properly understood lest the enterprise become a financial sinkhole. Relay 1 in turn would be the proverbial canary in the coal mine to measure the inimical effects of these energy particles as each critical system was made redundant with a backup in the event of a malfunction. After the first launch in 1962 the second satellite in 1964 boasted upgrades with shielding far more resilient to radiation than the preceding prototype. Relay 2 learned from its sibling and later broadcast segments of the Winter Olympic Games in Austria a few days upon the start of its mission. The program was the first to master real-time communication.

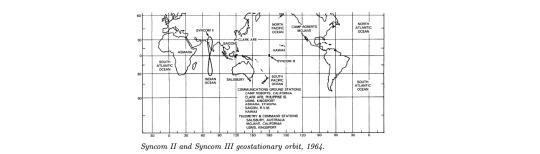

In the saga of Cold War politics America paraded its soft power with the apotheosis of Syncom that followed in the footsteps of the foregoing Relay program. Although less romanticized in the public imagination than the lunar missions but of equal salience this final prototype sought a geostationary orbit above the equator relative to a fixed point on the ground. Such a static position aloft in space relayed signals for one-third of Earth in a revolution for telecommunications. This portmanteau of ‘synchronous communication’ epitomized a giant leap in technology. At an altitude of 35,768km the parity of speed between Syncom and Earth’s rotation intimated the satellite could synchronize with one location on the terrestrial surface and hover above it. In this precise position the system and its solar cells would be continuously recharged by the sun. Whilst minor propulsion difficulties hobbled Syncom 2 with its figure-eight pattern above the sky after its predecessor completely floundered the third iteration nudged itself into the coveted spot of a geostationary orbit. Instant communication was made a reality as Syncom became globalization’s progenitor where citizens were no longer spectators but rather participants to world events. NASA thus created an information super highway for the world.

In the pyrotechnics to explore and exploit the final frontier the connectivity that ensued from transmitting voice, data and video via microwaves irrevocably changed the world economy. Analogous to President Theodore Roosevelt’s industrial policy of building the Panama Canal in 1904 meant to truncate the journey around South America’s Cape Horn did NASA’s satellites induce a similar vector of growth. Government funding coupled with public-private alliances integrated markets akin to how faster transit by ship aroused the same effect although the latter clearly manifested in more analogue ways. The Information Age cultivated by satellite technology came to midwife a multi-billion dollar industry whose downstream effects hastened economic globalization. Traders on Wall Street could navigate London and Tokyo stock exchanges devoid of any lag in financials. Multinationals began to exercise greater agency in managing supply chains. Media transcended borders to diffuse a monoculture of capitalism amidst the spectre of sabre-rattling from Cold War hostilities. A digital Silk Road thereby homogenized markets as transaction times were whittled down from days to seconds. Commerce then seized upon the alacrity at which capital moved since geographical determinism was no longer germane to growth.

0 notes

Link

President Dwight D. Eisenhower | Letters, Speeches, Etc.

#eisenhower#president eisenhower#dwight d. eisenhower#presidency#iran#oil#iranian#tehran#us foreign policy#us history#us politics#president#us president#us presidents#swede hazlett#presidential records#history#cold war#childhood friends#pen pals#letters#us military#korean war#1950's#greece#turkey#china#guatemala#egypt#communism

0 notes

Text

It is so fucking weird that Eisenhower influenced fashion.

1 note

·

View note

Text

An AI Art Thread Literally No One Asked For — U.S. Presidents As Disney Princesses

#art#u s presidents#bush#obama#roosevelt#eisenhower#clinton#potrait#portraits#portraiture#weird#weirdness#humor#washington#trump#paintings

109 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Adlai Stevenson would have been a good president if he'd won in 1952 or 1956?

I'm sure Adlai Stevenson would have been a perfectly acceptable President. I think the Eisenhower vs. Stevenson campaigns in 1952 and 1956 were rare examples of the country actually nominating two of the very best possible candidates for President at the time.

#History#Presidential candidates#Presidential Elections#1952 Election#1956 Election#Adlai E. Stevenson#Dwight D. Eisenhower#Eisenhower vs. Stevenson#President Eisenhower#General Eisenhower#Adlai Stevenson

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

shoot me

#dwight eisenhower#harry s truman#richard nixon#john f kennedy#abraham lincoln#theodore roosevelt#us presidents#u.s presidents#jfk

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

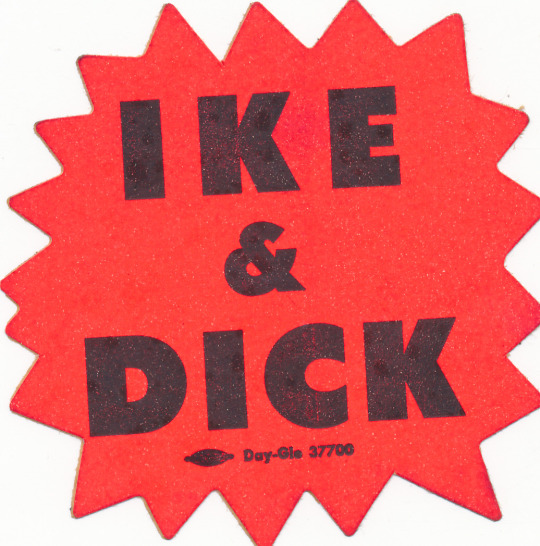

Recent Acquisition - Ephemera Collection

IKE & DICK.

Political sticker.

Florence Marie Longest Scrapbook

#dwight d. eisenhower#richard nixon#president#vice president#campaign#political#politics#vintage#1950s#ephemera

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Readers who have seen Christopher Nolan's biopic about the life of physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, credited by some as "the father of the atomic bomb," may have been curious about one scene that included a brief mention of a famous former U.S. president: John F. Kennedy.

Was the inclusion of Kennedy's name in relation to what was happening in the story a real historical fact? Did Kennedy truly vote against U.S. President Dwight D. Eisehower's cabinet nomination for Lewis L. Strauss, the former chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, even after initially intending to vote in favor of him?

The answer was yes.

"Oppenheimer" was released in movie theaters on July 21, 2023. Strauss, a character who would eventually be revealed as Oppenheimer's nemesis and who helped engineer Oppenheimer's downfall, is portrayed by Academy Award-nominated actor Robert Downey Jr. As for Kennedy, he's only mentioned by name and does not appear onscreen.

During a pivotal scene toward the end of the film, Strauss, who had been serving under Eisenhower as acting U.S. secretary of commerce since November 1958, learns to his surprise that the senate nomination vote was not successful. This vote took place early in the morning on June 19, 1959.

In the film, Strauss is told that there were three holdouts, including Kennedy, a senator at the time for the state of Massachusetts.

On June 17, just two days before the vote, the Lewiston Daily Sun reported that Kennedy had reportedly originally intended to vote in favor of Strauss:

Another significant backstage development is that all the Democratic presidential aspirants are now definitely committed against Strauss.

In addition to [Senator Hubert] Humphrey, they are Senators Lyndon Johnson, Tex., John Kennedy, Mass., and Stuart Symington, Mo.

The three had been listed as undecided, with Johnson leaning against Strauss, and Kennedy and Symington for him.

Former President Truman is credited with winning over Symington.

Although appointing Strauss to the Atomic Energy Commission, Truman is now highly critical of him. Truman, a leading Symington presidential booster, had several telephone talks with his fellow Missourian, and apparently swung him against Strauss in the past week.

The reporting's mention of former U.S. President Harry S. Truman might bring to mind for "Oppenheimer" viewers the fact that he was portrayed in one scene, somewhat as an unpublicized surprise, by actor Gary Oldman. Oldman previously won the best actor Oscar for his role of another prominent figure in history – Winston Churchill – in the 2017 film, "The Darkest Hour."

"At 35 minutes past midnight, on June 19, 1959, in a packed Senate Chamber, the Strauss nomination died on a cliff-hanging roll-call vote of 46 in favor, 49 opposed," according to Senate.gov.

The official result was tallied...in the Congressional record...

About one week after the vote that denied Strauss his appointment, The Boston Globe published reporting about the rarity of the situation:

No Senate debate in recent history generated the political heat of that on the confirmation of Lewis L. Strauss as Secretary of Commerce.

In the early morning hours of June 19, Strauss became the eighth Cabinet nominee in history and the first since 1925 to be rejected by the Senate.

He was also the first nominee for any major post in the Eisenhower administration to be turned back by the Senate.

In Kennedy's letter to the Globe, which we were unable to find anywhere online other Newspapers.com, he expressed admiration of Strauss' "long public service," but said he had differences with "intense" efforts to lobby for votes.

The letter read, in part:

Why I Voted Against Him

Advertisement:

By Sen. John F. Kennedy

This nomination was one of the most difficult questions to come before the Senate during recent years.

I tried to approach the issue with an open mind and I attempted to judge it on its merits.

I held no personal grievances against Adm. Strauss, since I have had a pleasant social aquaintance with him and since I admire some aspects of his varied and long public service.

However, the case against Adm. Strauss' confirmation for this position became stronger as it was considered more intensively.

I read large portions of the hearings before the Senate Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee. That committee was disposed in Adm. Strauss' behalf two months ago.

However, the evidence presented by Adm. Strauss and by individual witnesses and the attitude which Adm. Strauss displayed regarding the constitutional relationship of the Executive and Congress and matters of public policy caused a sharp shift on that committee.

...

In the interval between the committee and the floor vote, members of the Senate were subjected to the most intense lobbying effort on Adm. Strauss' direct behalf that I can remember in some time.

All kinds of appeals and implied promises – many of them contradictory – were made to different senators.

This effort was properly resented not only by many Democratic senators, but also by several Republicans whose enthusiasm for Adm. Strauss' nomination dimmed considerably over the past weeks.

I think that this effort of garnering votes not only alienated some members of the Senate, but also cast considerable doubt on Adm. Strauss' freedom of action if he were confirmed.

I do not hold Adm. Strauss personally responsible for all of this activity, but it was undertaken with his knowledge and approval.

Later in the letter, Kennedy stressed the importance of what he contended was strong evidence on his side to oppose the nomination.

He ended his letter with, "I regret that the President insisted on Adm. Strauss' confirmation for this post after it became increasingly clear that he had lost the confidence of so substantial a segment of responsible opinion in the Senate and in the country."

Four years later, Kennedy had a hand in restoring Oppenheimer's reputation with his signing of a citation for Oppenheimer for the Enrico Fermi Award. The award was bestowed to Oppenheimer by U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson on Dec. 2, 1963, just two weeks after Kennedy's assassination, USA Today reported.'

#Oppenheimer#Lewis Strauss#John F. Kennedy#Enrico Fermi Award#Lyndon B. Johnson#President Eisenhower#Robert Downey Jr.#President Truman#Gary Oldman#Winston Churchill#The Darkest Hour#Christopher Nolan

0 notes

Text

What’s in a name: Colorado's Eisenhower Highway, Tunnel and Park

Have you ever noticed that many Colorado infrastructures are named after President and First Lady Eisenhower? Why? #Colorado

#Eisenhower #history #president

Have you ever noticed that many Colorado infrastructures are named after President and First Lady Eisenhower? Why?

Eisenhower Highway

In the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973, Congress named a transcontinental highway after Dwight D. Eisenhower, to commemorate the route of the extraordinary U.S. Army’s 1919 convoy.

Since many of today’s highways were not in existence in 1919 (as can be seen in…

View On WordPress

#Colorado highways#Dwight d Eisenhower#Eisenhower#Eisenhower highway#Eisenhower tunnel#highways#president#president Eisenhower#roads#transportation

0 notes