#postwar Russian poetry

Text

well, @illumiost asked to hear my Russian, so here's me reciting a poem that's very important to me.

This is "Страхи" (Fears) by the Soviet poet Evgeny Evtushenko, written 1962. The poem was set to music for the fourth movement of Shostakovich's 13th Symphony.

The historical context to this poem is vital to understanding it. After Stalin's death in 1953, Khrushchev's government came with some easing of cultural restrictions, and the decline of the "Socialist Realism" art style, most prominent in the 30s-50s. This period of Soviet history is known as the "Thaw." While the Thaw resulted in a rise in avant-garde Soviet art, it was still heavily discouraged, albeit not to the extent that it was during Stalin's time in power; while the fact that this poem makes an appearance in Shostakovich's symphony is indicative of the changing cultural atmosphere, it also faced censorship and controversy (albeit not to the extent of another Evtushenko poem featured in Shostakovich 13, "Babi Yar").

The poem alludes to two major historical events that defined Soviet culture during the Stalin era- the Great Purges (1936-38) and WWII (in the Soviet Union, 1941-45). During the Purges, a culture of fear and distrust grew, and while the war resulted in devastating losses of life, wartime and postwar propaganda pushed an image of Soviet strength and military power. This cognitive dissonance between fear and trauma caused by one's own government, while projecting a cultural image of patriotic might and confidence, is reflected in the poem as well.

Overall, "Страхи" is a poem about the lasting presence of cultural trauma and its consequences for Soviet Russia (and, one could argue, modern Russia). The first and last stanzas contain the line, "Умирают в России страхи" ("in Russia, fears are dying"), but as the rest of the poem states, this is not the case. Fear is still as alive in 1962 as it was in 1936, and it manifests as mistrust and a wariness to speak out against oppression. The poem purposefully contradicts itself multiple times; fears are dying in Russia, but they still permeate Russian society. Russians were unafraid of warfare during WWII, but were terrified of speaking aloud to themselves at home.

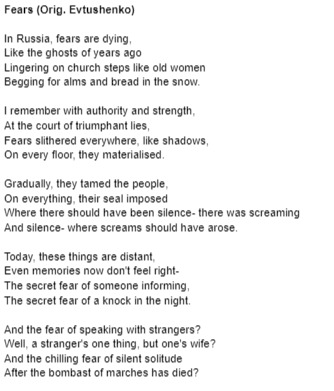

Here is my original English translation of "Страхи." It's not a one-for-one literal translation, but I did my best to preserve both the meaning and the original rhyme scheme.

In 2022, before Russia invaded Ukraine, I was taking Russian language classes in college in order to further my music history research. I was invited by my Russian professor to participate in the Evgeny Evtushenko poetry competition, which required Russian learners (both students learning Russian as a foreign language and heritage speakers) to recite a Russian-language poem on a Zoom call. Evtushenko's widow and son were on the judges' panel. As I was familiar with some of his work and knew he collaborated with Shostakovich- a composer whom I had been enamored with researching- I signed up for the competition and chose this poem, as I was already familiar with it from the symphony. My professor was surprised I decided to choose such a long poem with that sort of historical weight to it, but agreed to help coach me with the pronunciation and enunciation.

Reciting this poem in front of her was difficult, even before the war began. My professor grew up in Russia, and I didn't want her to think I was taking the poem lightly by any means; I was dealing with serious subject matter from a culture I was not a part of, and while my historical research had helped me somewhat understand what the poem was about, I knew there was a cultural component to it that I would never be able to fully grasp. However, my professor encouraged me to learn the poem, and urged me not to shrink away from some of the more cutting stanzas.

I was probably halfway through memorizing it when the invasion happened, and that made me gain another layer of understanding. Going on Reddit and reading posts from Russians who had previously dismissed the idea of an invasion of Ukraine as "western propaganda," only to be completely shocked and disillusioned when the invasion actually began, hearing how scared my friends in eastern Europe were, reading news reports of protesters being arrested just for holding anti-war signs, and seeing the war be met with apathy or claims of being "apolitical" by civilians as it went on made it harder to learn and recite the poem, as I was beginning to see just how relevant it was.

One day, I read a news report that a memorial in Babyn Yar, Ukraine, had been damaged by bombing- the site of the 1941 anti-Semitic massacre where, in 1962, as stated in the Shostakovich 13 setting, there "was no monument." When I went to practice the poem that day in front of my professor, I broke down crying. 1936 became 1941 became 1962 became 2022, and that day, I felt as if I had caught a glimpse of the impossible length of history.

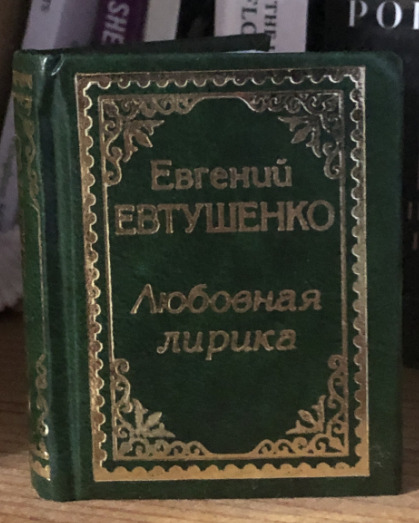

I can hardly remember being on the Zoom call and reciting the poem for the Evtushenkos. I couldn't believe I was actually speaking to them, and that they were listening to me recite the words of the famous poet- to them, a husband and father- who had collaborated with the Dmitri Shostakovich on one of the most monumental symphonies of the 20th century. I wish I could have looked at their faces on the screen, but I didn't; I just recited and then listened to the rest of the students read their poems. I didn't win the competition, and didn't even place, but a few weeks later, my Russian professor handed me this small book of Evtushenko poems, which she said the Evtushenko family wanted to give me. It's by far my most prized possession.

#poetry#russian#russian language#language learning#evgeny evtushenko#evtushenko#yevtushenko#yevgeny yevtushenko#shostakovich#dmitri shostakovich#ukraine#russo ukrainian war#history#current events#long post

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

"the distance ever more westerly"

“the distance ever more westerly”

the distance ever more westerly

footsteps steadily darken,

the stars still do not suffice

to think about the water,

but the first bridges —

predawn bridges as it were —

fracture the night

brilliantly nowhere.

child, let’s bid farewell here,

in the coldness of this line

the word’s color is forever white,

only meaning is not eternal.

the february water

is even blacker than the light

looming over…

View On WordPress

#neo-avant-garde#neo-futurism#postwar Russian poetry#Russian Futurism#Russian poetry in translation#Vladimir Kazakov

0 notes

Photo

—Daniel Immerwahr, “A New History of World War II”

Speaking of Immerwahr, as I was in my Dune post, here he is in The Atlantic—surprisingly. I think of The Atlantic as the house organ of refighting World War II. Even in their woke turn, heralded by the rise of Ta-Nehisi Coates, they sought to refurbish the “Good War” idea by moving it back a century to the Civil War, since the neoliberals and neoconservatives had worn out the World War II analogies in the 1990s and 2000s.

Still, to demythologize World War II in this way—tantamount to desacralizing Hitler as the incarnation of metaphysical evil in modern history, as I think Old Nick (I mean Land) once called him—is to invite moral chaos, to strike at the foundation of the liberal world order. This was the point of my post about Milan Kundera and Toni Morrison when this year’s war first began.

I think of how such gestures were received in what seemed like stabler times. My own touchstones are literary. Hilary Mantel’s rebuke of The English Patient comes to mind:

Kip trains his rifle on the “English patient” and is reminded that no one quite knows who the man is.

“American, French, I don’t care. When you start bombing the brown races of the world, you’re an Englishman.”

It is a crude polemic, this, exploding into the final pages of the book. As Ondaatje has neglected or disdained or is disinclined to set up a mechanism to distinguish his views from those of his characters, we wonder whether he is speaking for himself. It is fashionable to pretend not to know why certain wars were fought: Does this incomprehension now stretch to World War II? Is there no truth that jumps out of its skin—white, brown, burnt—to embrace the postwar generation?

To fight the reactionaries over the last decade or so, the liberals have armed themselves with the revolutionary tradition. After gratuitously insulting Corey Robin on the last episode of GPA, I sat down with the 2018 expanded edition of The Reactionary Mind and was reminded of what I found to be its appealing but debilitating simplicity a decade ago, even leaving his aside his obvious envy and longing, his libidinal attachment to the dynamism and creativity of the reactionary style. (The true homme de lettres will always prefer Burke to Paine, Nietzsche to Marx.) And yet, assigning “reactionary” without qualification to critics of the French, Russian, and Chinese revolutions and to the partisans of the Old South in America is not only to tie the knot too tightly but even to imply a John Birch shadow book in which Robespierre, Lincoln, Roosevelt, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, and Obama all stand revealed as exemplars of one ideology.

The revolutionary tradition has its own World War II mythos, of which Putin’s line about the Nazis in Ukraine is a remnant, but because of its anti-colonial aspect it was never going to be able to sustain the idea of Nazism’s novelty or uniqueness. There are two possible responses to the idea that Nazis are neither novel nor unique: to disown one’s own tradition as no better than Nazism or to accept Nazism as integral part of one’s own tradition. Between Immerwahr’s discourse on colonialism in The Atlantic and Richard Spencer’s EU flag-waving on Twitter, the liberal west is decomposing into incompatible ideologemes under the strain of the new century, while some of us—reared in the old regime—are just trying to hold on.

I’ve always liked The English Patient. Overheated rhetoric, sure, a lot of poetic misfires, though who by that era (or our own) had or has time for the Balzacian breadth Mantel demands in the stead of Ondaatje’s poetry? (I’ve never read any of Mantel’s long novels.) But when the heroine Hana writes home to her mother after Hiroshima, “From now on I believe the personal will forever be at war with the public,” she makes the novel’s real point, a point of the type literature exists to make if literature exists to make points, about the ironies and affects of private life amid the mythological clash of peoples, identities, and ideologies. “There is no such thing as the individual,” the righteous of all sects tell us. But it’s still the individual who has to live out the wars.

Of my older relatives who fought in World War II, the one who saw the most combat, my great uncle on my father’s side, was the one who suffered most: blown up behind German lines, his eye torn out, the left side of his face ripped open. Then, starving, infected, feverish, in agony, he was a prisoner of war. He had gone away excited to fight; he came back half shattered in body and mind. He never had a good word to say about the good war. In a memoir of the fighting he wrote for a VA psychiatrist to upgrade his veterans’ benefit claims in the 1970s—I have it here—he recounts his time as a prisoner of the Germans:

They had us get out of the boxcars. They marched us through the dark tunnel. When we came out of the tunnel we saw a river. I think it was the Rhine River. There was a bridge and it was on its side but it was still standing. They marched us across the bridge, then up to a high ridge. On this ridge coming toward us was a young German soldier. He looked at us so pitifully. I said “Good Morning” to him in German. Then I said in German, “War is hell!” He agreed.

No Ondaatjean poeticisms, just the pathos and panache of Hemingway. When he died, my grandmother had the words TOO MUCH WAR carved into his tombstone.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NOVELS IN VERSE

Have you ever read a novel in verse? The young adult genre is rife with popular novels told in poems … and they appeal to adults as well. Add to those classic and contemporary tales written for adults and included in our round-up of acclaimed and prize-winning novels in verse:

THE LONG TAKE: A NOIR NARRATIVE by Robin Robertson

Finalist for the 2018 Man Booker Prize

From the award-winning British author—a poet’s noir narrative that tells the story of a D-Day veteran in postwar America: a good man, brutalized by war, haunted by violence and apparently doomed to return to it, yet resolved to find kindness again, in the world and in himself.

THE GOLDEN GATE by Vikram Seth

“The great California novel been written, in verse (and why not?): The Golden Gate gives great joy.”—Gore Vidal

One of the most highly regarded novels of 1986, Vikram Seth’s story in verse made him a literary household name in both the United States and India. John Brown, a successful yuppie living in 1980s San Francisco meets a romantic interest in Liz, after placing a personal ad in the newspaper. From this interaction, John meets a variety of characters, each with their own values and ideas of “self-actualization.” However, Liz begins to fall in love with John’s best friend, and John realizes his journey of self-discovery has only just begun.

EUGENE ONEGIN by Alexander Pushkin, translated by Stanley Mitchell

Still the benchmark of Russian literature 175 years after its first publication, Pushkin’s incomparable poem has at its center a young Russian dandy much like Pushkin in his attitudes and habits. Eugene Onegin, bored with the triviality of everyday life, takes a trip to the countryside, where he encounters the young and passionate Tatyana. She falls in love with him but is cruelly rejected. Years later, Eugene Onegin sees the error of his ways, but fate is not on his side. A tragic story about love, innocence, and friendship, this beautifully written tale is a treasure for any fan of Russian literature.

HISTORY: THE HOME MOVIE by Craig Raine

One of England’s foremost poets, Craig Raine offers a “bold, ambitious chronicle of life” (New York Times Review) told through the stories of two families, the Pasternaks and the Raines, who touch each other and are touched by history in different ways. Like a home movie, this novel in verse masterfully conjures the world in which these families move by re-creating the texture of ordinary and extraordinary life. Blending fact, fiction, and thrilling leaps of imagination, History: The Home Movie promises to be the film you’ll ever read.

FOR YOUNGER READERS

SKYSCRAPING by Cordelia Jensen

A YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults title

Mira is just beginning her senior year of high school when she discovers her father with his male lover. Her world–and everything she thought she knew about her family–is shattered instantly. Unable to comprehend the lies, betrayal, and secrets that–unbeknownst to Mira–have come to define and keep intact her family’s existence, Mira distances herself from her sister and closest friends as a means of coping. But her father’s sexual orientation isn’t all he’s kept hidden. A shocking health scare brings to light his battle with HIV. As Mira struggles to make sense of the many fractures in her family’s fabric and redefine her wavering sense of self, she must find a way to reconnect with her dad–while there is still time. Told in raw, exposed free verse, Skyscraping reminds us that there is no one way to be a family.

THIS IMPOSSIBLE LIGHT by Lily Myers

From the YouTube slam poetry star of “Shrinking Women” (more than 5 million views!) comes a novel in verse about body image, eating disorders, self-worth, mothers and daughters, and the psychological scars we inherit from our parents.

THE REALM OF POSSIBILITY by David Levithan

Enter The Realm of Possibility and meet a boy whose girlfriend is in love with Holden Caulfield; a girl who loves the boy who wears all black; a boy with the perfect body; and a girl who writes love songs for a girl she can’t have.

David Levithan plumbs the depths of teenage emotion to create an amazing array of voices that readers won’t forget. So, enter their lives and prepare to welcome the realm of possibility open to us all. Love, joy, and these stories will linger.

FULL CICADA MOON by Marilyn Hilton

It’s 1969, and the Apollo 11 mission is getting ready to go to the moon. But for half-black, half-Japanese Mimi, moving to a predominantly white Vermont town is enough to make her feel alien. Suddenly, Mimi’s appearance is all anyone notices. She struggles to fit in with her classmates, even as she fights for her right to stand out by entering science competitions and joining Shop Class instead of Home Ec. And even though teachers and neighbors balk at her mixed-race family and her refusals to conform, Mimi’s dreams of becoming an astronaut never fade—no matter how many times she’s told no.

This historical middle-grade novel is told in poems from Mimi’s perspective over the course of one year in her new town, and shows readers that positive change can start with just one person speaking up.

For more on these, and related titles, visit the collection Novels in Verse

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE LOST GIRL’S HOME IS IN BOOKS: spring leisure reading

Girl Reading (1850), oil on canvas, Andre Fontaine

Writing on my phone. On the train. Woke with a sore throat. Snow outside the Manhattan window turning to sludge and then puddles. In the morning Alex and I made our way to Tisch to pick up books from Wendy and sit in on Fred Moten’s class. He spoke for three hours about a paragraph in Zalamea’s Synthetic Philosophy of Contemporary Mathematics, constellating the Isley Brothers with quantum physics with the history of slavery with Solange with financialization with the spatio-temporal dimensions of Judaism with critiques of the individuated liberal subject. In Fred’s presence I’m always in awe. When he says the stream of thought will go where it goes, I know what he means, what it feels like, to want to read everything. To have no filters. To be a being who is…interested. “You know, it’s like a river that winds through all these different terrains, and part of it winds through the history of science, and part of it winds through category theory and general topology, and part of it winds through Russian cinema—I’m just interested.” (Moten)

Would like to linger more on the things I read and not just mark passages to return to…later. Has grad school de-skilled me? Has the process of becoming a “historian”—of having to read thousands of pages per class in grad seminars destroyed my ability to read slowly? Poetry is becoming harder to read. It demands a kind of attention other than the kind of attention I have become accustomed to—the temporality forced into me by the academic grind.

Last semester I did my comprehensive exams. For two hours I was quizzed by 4 professors on the contents of ~400 books. My fields were: Prisons and Police; History and Political Economy of Race in America; Social and Political Theory (Marxism, psychoanalysis, critical theory, Frankfurt School, feminist/queer theory, post-structuralism); and Black Literature, Theory and Cultural Studies. “Studying” for my exams hardly felt like studying at all—I was just doing what I’ve always done: read.

But the thing about being in academia is…you can’t just read what you want to read (unless you’re Fred!), you’re supposed to specialize. Your supposed to read within your discipline, to be monogamous with your dissertation topic. But sometimes…my mind needs ventilation. I need to let my mind wander. So this spring break I went on a kind of “retreat”—I rented a little eco-bungalow on a mountain overlooking the ocean in Deshaies, Guadalupe, with the intention to do nothing except read, journal & spend time in nature. It’s weird to now have a life where I have to schedule in these compressed snatches of leisure. Between my academic life and artist/public intellectual life all life is becoming work work work. Constant travel, mountains of assignments to grade, grant applications, bureaucracy, student emails, assigned readings, lesson planning, talks—in psychoanalysis I am sometimes too fatigued to finish my sentences.

What was it? “The disquieting feeling that we don’t own ourselves.” My poor journal, neglected since last semester. Turned inside-out and called into presence by the Pavlovian PING of the push notification. Life becomes the work of feeding the avatar. It’s nothing new. It’s the same ole subject formation, in overdrive. The you of I (alienated Lacanian subject) — identification with an image of self that circulates as…I-am-that. When the avatar takes over your life, when you become what the public makes you…how can you find a way to re-inhabit your life as you? Quiet. Unplug. Has busyness evacuated my inner life? I’m still me. But look at how much my situation has changed…

Here are my notes on the books I read over spring break (some finished the week after I returned…)

Tolstoy - Anna Karenina

My skin takes it in. Ghosts enter and leave this vessel, Sunship Earth. Body, too, will become a ruined beach house covered in pale violet morning glory vines, its shutters still hinged shut. Now Nabokov is analyzing the varied march of time in Tolstoy—there is something like a moral in Kitty and Levin’s slow dance, against the locomotive thrust of Anna and Vronsky.

A road—to where? The bull in the clearing, the smell of the tiny yellow flowers and the fade, the gloaming, the wall of water, peach-haloed in the sunset. The dimming, the peep of the first cicada, the crushed cicada that lost its way, the dream that wrote her destiny, the dirty peasant rooting around in the sack—the man split by the wheels of the locomotive. A force that nothing, no one escapes. [Holy shit. As I type these notes from my journal my train has been stopped in Providence because the train ahead of us hit someone]. Yes, I have had the dream of the man with his hand in my sack [“It was crowded in the market. I was trying to photograph the flowers but the image was distorted because a man had his hand in my backpack”]. Can a sudden silence wake a sleeping body? I think, as I wake, that I have caught the day in the precise moment of transition. What crossed over then, the wind swept the island clean. Like Anna Karenina I have been under the spell of the dream: what I now no longer know if I can trust.

Nothing could have saved Anna

the terrible omen flashing above her life…

Nabokov - Lectures on Russian Literature

Freud and Baldwin love Dostoyevsky. Nabokov loathes him. What does that tell you about the kinds of people who love and hate Dostoyevsky? Lovers of Dostoyevsky: hysterics, neurotics, fringe-dwellers, madmen. Dostoyevsky is to literature what Zulawski is to cinema (emotional excess–which is why teens also love Dostoyevsky). This whole book is an argument for Tolstoy and against Dostoyevsky. Lovers of Tolstoy: the good, the moral, the erudite, Oprah. Nabokov is a snob à la Adorno, but his lectures on Tolstoy are damn good (skip the ones on Dostoyevsky), especially the ones on dreams and time in Anna K.

Nabokov and Barabtarlo - Insomnia Dreams

This book is pretty fucking cool. It is an inventory of Nabokov’s proleptic dreams, which he wrote down on notecards after reading J. W. Dunne’s An Experiment with Time. Dunne was an aeronautical engineer and crackpot philosopher who developed what I sometimes call stoner dream theory. He believed that past-present-future exist simultaneously and that the experience of time as an arrow moving forward is an effect of waking consciousness. In dreams we are unhitched from normative time and can access the future–are touched by future events.

Notebook notes:

Dunne and Nabokov dream to know time in every direction. So future events loop back to pierce our sleeping heads. Did I believe—the future is making contact with me. What did the dream corrupt? I could not outrun it. Nabokov dreaming of South Station [strange, that’s where I’m headed as I type up these notes…].

Dreams of the lepidopterist: chasing the butterflies with a giant spoon instead of a net. Sometimes he’s an insufferable pedant. But even pedants can have a compelling dream life…

Lemov - Database of Dreams: The Lost Quest to Catalog Humanity

Professor Lemov teaches in the History of Science department at Harvard. She is currently a faculty fellow in a year-long Crime and Punishment seminar at Harvard that I am also a part of. I first got interested in her work after she presented an excellent paper on the history of Cold War behaviorist experiments (many of which were conducted on prisoners, including the practice of “psychosurgery”) and early efforts to use data to construct psychological theories of deviance. When I found out she wrote a history of a dream database, I knew I had to read it.

This book is a history of Bert Kaplan’s ambitious mid-20th century quest to create a database of dreams and psychological data (called the Primary Records in Culture and Personality), which consists of a collection of the raw notes of the thoughts, feelings, and dreams of people from around the world, stored on the now-obsolete technology of the Microcard. It is at once a history of: microfilm technologies, data science, the information storage ambitions of postwar social scientists and anthropologists, and psychologists’ obsession with the dreams and unconscious thoughts of ethnic “others.” The story of the database is fascinating in itself…but I wanted to know more about what was in the repository. Sometimes the unconscious speaks:

“A man named Birch Tree told of a dying young man of his acquaintance who had dreamed too ambitiously: one night, he was able to see ‘every leaf in the whole world’ and perished soon after, like the leaves that fall from the trees each year.”

“dream #19, in which he was shooting birds, surrounded by sunflowers as big as evergreen trees”

“Dreams were “palimpsests for understanding what could be called ‘not-self,’ the place at which the self begins to shade away into nothingness or something else.”

“If you sat in a library looking at someone’s dreams, what were you seeing?”

The database of dreams was dead on arrival.

But there’s another living database of dreams assembled by oneirologist Kelly Bulkeley: http://sleepanddreamdatabase.org/ – have read and enjoyed several of Bulkeley’s books too. The convocation of the oneirologists…

Sliwinski - Mandela’s Dark Years

How strange, I read this two days before the death of Winnie Mandela. Did Nelson dream of Winnie while in prison? There is a lot to chew on in this little book. I keep returning to the dream that is circled in the text, Nelson Mandela’s dream from prison:

I had one recurring nightmare. In the dream, I had just been released from prison—only it was not Robben Island, but a jail in Johannesburg. I walked outside the gates into the city and found no one there to meet me. In fact, there was no one there at all, no people, no cars, no taxis. I would then set out on foot toward Soweto. I walked for many hours before arriving in Orlando West, and then turned the corner toward 8115. Finally, I would see my home, but it turned out to be empty, a ghost house, with all the doors and windows open, but no one at all there.

The subject in absentia dreams their erasure while in prison, the experience of becoming-ghost. (Mandela’s recurring nightmare. How apartheid structures the geography of the unconscious…)

Szabó - The Door

“If there was [an] article about what to read once you’ve finished Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels, The Door—though it lacks the scope of those books—might top the list.” I read no such list but did finish the Neapolitan novels last year. I read The Door after it was recommended by 3 of my feminist friends.

To say what this book is about would fail to get at the experience of reading this book. It’s deeply disturbing and all the more so because Emerence, the narrator’s housekeeper, is the exact likeness of my aunt Helen. They are women for whom every emotional door has been sealed shut. They both had dogs that were passionately attached to them. Under what conditions does the wound grow into an impenetrable shell? Grow into the pride of self-sufficiency…

Notes:

The book is bookended by a recurring nightmare of a door that won’t open. An ambulance outside, and the silhouettes of paramedics seen through glass. Most of my dreams are about the absence of shelter, porous structures, rooms that are always open to invaders. But here is a nightmare about being trapped inside with someone in need of help. Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment resonates too.

Resonances.

Lightning strikes the two babes Emerence was fleeing with. In Anna Karenina, lightning missed Kitty and child. The plots of two novels are crossed. What characters evade in one novel befalls characters in another. It’s like the books are talking to each other through the body of me.

Schmitt - Political Theology

We should discuss this book in person. My thoughts are too sprawling to give shape to them here. People on the left read Schmitt for his critique of liberalism and though there are parts of it I find compelling (I’ve elaborated the concept of a “financial state of exception” in my book Carceral Capitalism), the part about liberal democracy lacking decisionism because it’s weighed down by a Weberian bureaucracy is, I think, wrong. Well, that’s what I felt while reading McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century immediately following Political Theology.

McCoy - In the Shadows of the American Century

This book is part of an ever-growing body of literature on the decline of US hegemony and the rise of China as a global superpower. But what this book adds to the analysis is a thought-provoking discussion of the changing nature of geopolitical struggles–from a navel-based strategy to a land-based strategy. McCoy unpacks the influence of Halford Mackinder’s theory of the Geographical Pivot of History, which posits that the future belongs to whoever controls the Eurasian landmass (the World-Island). During the Cold War the US has maintained its hegemony by controlling key axial points–through NATO in western Europe (on the west side of the World-Island), and the strategic positioning of military/naval bases around the Pacific, and the forging of political and economic alliances with South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, etc. This book is a good overview of how the US built and maintained its empire, and offers possible blueprints for its decline (McCoy’s analysis of Obama’s attempts to salvage US hegemony through his “pivot toward Asia” and Trump’s acceleration of the decline of US hegemony was interesting…). After reading about the CIA’s covert operations in Latin America I felt that liberal democracy is not at all lacking decisionism, as Schmitt says, but like all states it maintains its power through brute force (militarism/war), international diplomacy, strategic alliances, soft power, proxy warfare and covert operations, international trade agreements, technological prowess, surveillance, etc.

Saterstrom - Ideal Suggestions

What is the relationship between what is seen and unseen?

Saterstrom’s poetics can be summed up by her line: “dust mote footing the invisible”–the “thing” itself is often absent, even as it mutates everything present, but there are ways to access ghosts, traces, invisible forces, and the disappeared. Like a projection that flashes when it catches smoke in the phantasmagoria–you can catch it in the transition.

The form of the book is satisfying. I enjoy the way it alternates between ars poetica and the enactment of the poetics it is trying to sketch.

Notes:

“In the other world everything also exists. But in versions complicated by the softness that dissolution makes.”

“what happens between women when the center of female triangulation is scarcity and lack?”

Simone Weil: “When a contradiction is impossible to resolve except by a lie, then we know that it is really a door.”

divinatory poetics as a way to bear “the absurdity and enchantment of human experience”

to write from “within the membranous precincts between our multiple bodies in the larger rhizomatic field of resonances, where much is sounding and is also unsounded.”

Christian Hawkey: “the holes in our bodies and skulls are voice chambers, sound chambers, wherein our own voiced selves and the voiced selves of others constantly enter and exit, and are changed by our bodies upon entrance, exit. Consciousness…is less a vehicle for “self-presence” than a void, a blank space at the site of intersection.”

“the friendship of our ghosts”

“A raw garnet dug up from earth appears as a piece of burned glass and smells of warm dirt. How did this garnet come to rest here, pinned between sky and sea, a mineral between the here and hereafter? Lines made through the absenting of lines, they suggest their phantom shapes into calligraphy. And someone arrives, a dead poet, she writes in an elegant script a poem about geese. It is a melancholic poem featuring geese, a landscape, and reflections about death. How do the deceased live within the blurred calligraphic strokes dependent upon whatever it was we erased? Who was here first? The process of being read, truly read. One day our lines appear in some other’s erasure.”

Where Freedom Starts (an anthology of essays on #MeToo)

This is an excellent collection of essays on #MeToo that captures the spectrum of feminist responses to the nascent movement. It includes black feminist critiques of carceral feminism, a discussion of black and Latinx vulnerability to sexual violence in the sphere of domestic labor, queer critiques of moral sex panics, feminist analyses of social reproduction, analyses of how undocumented women are hyper-vulnerable to sexual assault in the workplace (and at risk of deportation if they report sexual abuse), and more. I appreciate that many of these essays attempt to grapple with the emotionally and politically messy aspects of sexual violence–How do we determine the category or degree of the harm done? What you do when you feel ambivalence toward your rapist and internalize blame? How is victimhood constructed? I plan to return to these topics and questions in an essay I hope to write in May.

**This ebook is free from Verso.** Get it here.

Marina Van Zuylen - The Plentitude of Distraction

If I ever teach my Lost Girls class on the poetics of wandering, I would definitely include this book!! So, so good. Yes, the poet needs to give herself over to her reveries. To luxuriate in the waywardness of experience–the soul cut loose.

Notes:

Darwin’s great regret: “Up to the age of thirty, or beyond it, poetry of many kinds … gave me great pleasure, and even as a schoolboy I took intense delight in Shakespeare, especially in the historical plays. I have also said that formerly pictures gave me considerable, and music very great delight. But now for many years I cannot endure to read a line of poetry: I have tried lately to read Shakespeare, and found it so intolerably dull that it nauseated me. I have also almost lost my taste for pictures or music…. My mind seems to have become a kind of machine for grinding general laws out of large collections of facts, but why this should have caused the atrophy of that part of the brain alone, on which the higher tastes depend, I cannot conceive…. If I had to live my life again, I would have made a rule to read some poetry and listen to some music at least once every week; for perhaps the parts of my brain now atrophied would thus have been kept active through use. The loss of these tastes is a loss of happiness, and may possibly be injurious to the intellect, and more probably to the moral character, by enfeebling the emotional part of our nature.”

Discussed this Darwin passage with my analyst for some time. I don’t want to become a work machine! Give me “delicious idleness”!

“stop measuring your days by what you can report to your boss or to your conscience”

waywardness: “reveries unfasten him from his constructed social persona, eventually converting dispersal into a gathering of self-hood”

Blaise Pascal, Pensées: “The only thing that consoles us for our miseries is diversion. And yet it is the greatest of our miseries. For it is that above all which prevents us thinking about ourselves and leads is imperceptibly to destruction. But for that we should be bored, and boredom would drive us to seek some more solid means of escape, but diversion passes our time and brings us imperceptibly to our death.”

“the pure pleasure of a contemplative experience”

“It is not too late to side with some of the great propagandists of wasted time, with the practitioners of reverie, and cultivate the pleasures and pains of mental mayhem.”

Marx - Capital Vol 1

It’s always a good time to re-read Marx. In December I started a Capital reading group with my comrades LaKeyma and Joohyun. Marx is best read with your women of color crew!

Sithole - Steve Biko: Decolonial Meditations of Black Consciousness

Did an event with the incredible Tendayi Sithole at NYU (moderated by Fred Moten and Wendy Lotterman), so I wanted to read Tendayi’s work on Biko before the event. Many parts of the book draw on Afropessimism to analyze Biko’s liberatory political philosophy. We had a long discussion (privately and during the panel) about Afropessimism’s reception in South Africa (”it’s given us a language to understand our predicament,” says Tendayi). Such good work, and such a wonderful person and poet too!! During the reading Fred said Tendayi and I “became a band.”

McGuckian - The Flower Master

Re-read this at the Deshaies botanical gardens in Guadalupe. Unfuckwithable. McGuckian is one of my favorite poets of all time. Also read the parts about McGuckian in Northern Irish Poetry and the Russian Turn. Had no idea McGuckian draws so heavily from Russian literature, and that she feels there is a natural kinship between Russians and the Irish due to their historical predicaments…

Harford - Fifty Inventions that Shaped the Modern Economy

Pop economic/business and tech history. Replete with compelling stories and fun facts about underappreciated inventions. The chapters I was most interested in were the ones about inventions that fundamentally transformed gendered labor (TV dinners, infant formula, the birth control pill). After a while this books started to annoy me because the novelty wore off and I can only handle so much praise of the so-called wonders of capitalism.

Brogaard and Marlow - The Superhuman Mind

I don’t think I’m any smarter after having read this book. It’s somewhere between pop science (in the style of Oliver Sacks) and self-improvement literature. The book tries to give you mental “hacks”–mnemonics and algorithmic mental shortcuts. Most of the the book describes case studies of people who have accidentally unlocked superhuman mental capacities as a result of a brain injury, stroke, etc…or they were just born neurologically atypical. Synesthetes have good memories. If you’ve ready any of the pop sci books on memory you already know these tricks… the Greeks have known about the Memory Room for a while too…

Still reading:

Moten’s Black and Blur

Anne Boyer’s A Handbook of Disappointed Fate

Doudna and Sternberg’s A Crack in Creation: Gene Editing and the Unthinkable Power to Control Evolution

Frank Stanford - The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The literary great’s 120th birthday is next month

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway was the emperor of the American prose narrative. With his short, declarative sentences and a view of life both heroic and tragic, Hemingway has inspired more writers and gained more imitators than any other American novelist. He wasn’t alone in fashioning a revolution in prose and poetry. By the late 19th century, the English language was getting bloated. The Romantic era had run its course. T.S. Eliot turned to the French symbolists for inspiration in both verse and new methods of expression.

Hemingway, for his part, was influenced by the great Russians, Tolstoy and Turgenev. Eliot was well-educated and multi-lingual. Hemingway could never stand four years on a college campus (it would drive him crazy), but he was no less scholarly. For both, reading bouts led to writing bouts.

Hemingway found his voice while living in Paris with his young bride. A decorated World War I veteran, Hemingway was bored with the frivolity of American life and so he arranged for newspaper work in France. In Paris, Hemingway ran with a fast crowd of expats who spent much time talking about art and life, but often little time at the writing table. The place for the in crowd was the Montparnasse, a café on the West Bank, full of gossip and intrigue. It was great fun, but Hemingway carried a great burden. The young man was full of stories. He had to take the next step and pour them out on paper.

Which he did. Hemingway retired to a quieter café down the block and got down to work on The Sun Also Rises. As important, he had started publishing short stories in those little magazines, periodicals with small circulations, but farm systems, so to speak, for budding writers. Top editors at top firms all read such publications as The Dial, Poetry and The Little Review, constantly on the lookout for up and coming talent.

Hemingway caught a break in the person and character of F. Scott Fitzgerald. The latter’s moment came in 1920 when his manuscript, This Side of Paradise, was under discussion among editors at Scribner’s. The older editors were against publication. Maxwell Perkins, however, laid down a marker: If Scribner’s wanted to take its fiction list into the new century, it would have to start with novels like the one the young Fitzgerald had submitted. The talented young man from St. Paul would get published and in time, establish himself as the voice of the Jazz Age.

Fitzgerald was also exceedingly kind with fellow authors. He envisioned Scribner’s as the publishing capital of American letters. He boosted Hemingway to Perkins. Hemingway’s short stories eased the way to publication of The Sun Also Rises. Fitzgerald also edited the manuscript, excising the initial chapter and starting the manuscript with the famous lines, “Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton.” Think of Ezra Pound’s editing of Eliot’s “The Waste Land.” It’s so similar as to be downright eerie.

With The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway captured the anxieties of the 1920s. His image was that of a swashbuckler, a hunter, a fisherman, a daring soldier. That was true, but Hemingway was a disciplined man. Five hours at the writing table took precedent over hunting and fishing expeditions. His upbringing was thoroughly middle class, the second child of six of an Oak Park, IL physician and a domineering mother. Hemingway’s father was a suicide, always bad news for the surviving sons.

#gallery-0-5 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 50%; } #gallery-0-5 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-5 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

For many an American boy, World War I was a chance for adventure, a way to escape the home front and find war glory in Europe. Hemingway’s wartime heroics were no myth. An ambulance driver, he became a hero to Italians for saving lives during combat. Back home in Illinois, he pined for Europe and its unfolding tragedy.

Hemingway was workman-like. If he was going to live as an expatriate, he would have to come through. Short stories, novels, non-fiction tumbled from his pen: To Have And Have Not, Death In The Afternoon, Green Hills of Africa and the stories: “The Killers,” “A Way You’ll Never Be,” “The Gambler, The Nun and The Radio,” “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.” Hemingway was very much a man of 1914, joining Eliot, Pound, James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis. The tragic grandeur of the postwar world meant a search for nobility in a shattered world.

It worked. When Hemingway started publishing, he declared that his work would be read by both high school dropouts and PhDs. It was. In 1938, Scribner’s brought out The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, a publishing event and a volume that once stood on the bookshelf of virtually every home in America. In 1940, Hemingway published his novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Perkins loved the novel (as did the public), but the legendary editor told friends that this was it for Hemingway. The man, Perkins was positive, had just published his last great novel.

Was it true? In 1951, Hemingway published a shorter novel, Across the River and Into the Trees. The critics were laying in wait, eager to take down the Champ of American Letters. The novel received poor reviews. Hemingway was a fighter (he managed a pro named Hank Ketchum and worked out in the ring on a regular basis). He rebounded two years later with The Old Man and The Sea, a novella set in the Caribbean. Hemingway’s heroes often died at the end of their adventures. However, Mary Walsh, Hemingway’s fourth wife, begged him not to kill off Santiago, the novella’s hero. Mary prevailed. The Old Man and The Sea was a sensation. Excerpted in its entirety in Life magazine, the issue sold five million copies off the newsstands. Publication brought a Pulitzer Prize and the 1953 Nobel Prize. Hemingway, the old prizefighter, was off the canvas and back on top.

Throughout the 1950s, Hemingway continued writing. But he did not publish. Was he afraid that works in progress—Islands in The Stream, The Garden of Eden, The Dangerous Summer—couldn’t live up to past efforts? Did he fear losing his crown? Hemingway loved Cuba. He was more at home there than in Paris or his home country. When Fidel Castro took power in 1960, Hemingway was advised by State Department officials to get out and in a hurry. Hemingway re-located in Idaho. It wasn’t enough. Hemingway’s death was first reported as a gun-cleaning accident. The truth came out a few days later.

Suicide wasn’t the end of Hemingway the published writer. After the shock wore off, there was poor Mary Hemingway, trudging up Fifth Avenue on the way to Scribner’s, manuscripts in a shopping bag. The mortal man was gone, but in the years ahead, his readers would stay plenty busy.

Long Island Weekly's Joe Scotchie takes a look at the work of novelist Ernest Hemingway, champion of the American sentence. The literary great’s 120th birthday is next month Ernest Hemingway was the emperor of the American prose narrative.

1 note

·

View note

Text

5 Ways the Little House on the Prairie Books Stretched the Truth

Visit Now - http://zeroviral.com/5-ways-the-little-house-on-the-prairie-books-stretched-the-truth/

5 Ways the Little House on the Prairie Books Stretched the Truth

For 80 years, Thornton Wilder’s Our Town has awed audiences. The American playwright’s delicate tale of small town American families at the turn of the 20th century is alive with humanity and poetry. Yet, there was a time when its content felt downright revolutionary.

1. OUR TOWN IS WILDER’S MOST POPULAR OF HIS MANY NOVELS AND PLAYS.

Today, Wilder is considered a titan of 20th-century American literature—and he’s the only person to have won the Pulitzer Prize for both literature and drama. His 1927 novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey was a commercial success and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1928. Ten years later, Our Town won Wilder his second Pulitzer, and first in the drama category. His third Pulitzer came in 1943, when his play The Skin of Our Teeth won the drama prize.

Wilder also wrote screenplays for silent films. And because Alfred Hitchcock was such an admirer of Our Town, the iconic director hired Wilder to work on the script for his 1943 thriller Shadow of a Doubt.

2. OUR TOWN IS A SIMPLE STORY ABOUT EVERYDAY AMERICANS.

Set in the humble hamlet of Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, the play follows the relationship of young lovers Emily Webb and George Gibbs, who meet, marry, and separate over the course of 1901 to 1913. In his 1992 book Conversations with Thornton Wilder, English professor Jackson R. Bryer wrote, “Wilder presents ordinary people who make the human race seem worth preserving and represent the universality of human existence.”

3. THIS FICTIONAL TOWN IS BASED ON A REAL PLACE.

Wilder spent his summers in Peterborough, New Hampshire, and he aimed to capture its simple charms in his characterization of the fictional Grover’s Corners. Years later, Peterborough would return the compliment. As part of a dual celebration of the town’s 275th and the play’s 75th anniversaries, Peterborough dedicated the intersection of Grove and Main streets to Our Town, erecting street signs that read “Grover’s Corners.”

4. WILDER WROTE OUR TOWN IN PETERBOROUGH AND ZURICH.

Wilder wrote part of Our Town as a fellow of the MacDowell Colony, an artists’ retreat established in Peterborough in 1907. He also worked on the play at an isolated hotel in Zurich, Switzerland, where he was the sole guest. “I hate being alone,” Wilder once lamented in a letter, “And I hate writing. But I can only write when I’m alone. So these working spells combine both my antipathies.”

5. WILDER WAS ALREADY AN ACCLAIMED WRITER WHEN OUR TOWN DEBUTED.

After winning the Pulitzer for his book The Bridge of San Luis Rey, Wilder turned his focus to Broadway, where he debuted his original play The Trumpet Will Sound. Then, ahead of Our Town, he created English-language stage adaptations for French playwright Andre Obey’s The Rape of Lucretia (a.k.a. Lucrece) and Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House. Both played on the Great White Way, in 1932 and 1937 respectively.

6. OUR TOWN BOASTED GROUNDBREAKING STAGING.

The play’s directions call for it to be performed on an unadorned stage: “No curtain. No scenery. The audience, arriving, sees an empty stage in half-light.” Simple set pieces like ladders and chairs come into play, but the actors use no props, and pantomime as needed to convey the story. The play’s narrator is named after an important theatrical crew position: Stage Manager. This crucial character has the power to communicate directly to the audience, but also can interact with the characters. Each metatheatrical element is meant to draw attention to the constructs within the medium of theater.

7. WILDER HAD USED SOME OF THESE TECHNIQUES BEFORE.

His one-act plays The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden (1931) and Pullman Car Hiawatha (1932) both had Stage Manager characters. Both also called for minimalistic set designs. Happy Journey used four chairs and a low platform to stand in for a family car; Pullman Car Hiawatha employed chalk lines and chairs to create train cars. But only Pullman Car Hiawatha has the Stage Manager address the audience directly as he does in Our Town.

8. OUR TOWN WAS A RESPONSE TO WHAT WILDER FELT CONTEMPORARY THEATER LACKED.

Before writing Our Town, Wilder expressed his disappointment with the quality of American theater. He feared the opulent costumes and spectacular sets of Broadway did a disservice to the written word. “I felt that something had gone wrong,” he wrote. “Finally my dissatisfaction passed into resentment. I began to feel that the theatre was not only inadequate, it was evasive; it didn’t not wish to draw upon its deeper potentialities.”

9. OUR TOWN WON INSTANT ACCLAIM.

The show made its Broadway debut to positive reviews. Some critics were puzzled, however, by its deceptive minimalism. “Sometimes, as it skips through the lives in a small New Hampshire town, it soars; but again it is earthbound by its folksy attention to humdrum detail. However it may add up, it is an intelligent and rewarding theatrical experiment,” wrote John Chapman in the New York Daily News.

The New York Times theatre critic Brooks Atkinson was more effusive in his praise. “Our Town is, in this column’s opinion, one of the finest achievements of the current stage,” he wrote.

Our Town‘s success transformed Wilder from a lauded writer to a critical darling. “He was now not merely a successful writer but a sage, a spokesman—a role that he seems to have relished, or at least tolerated,” Robert Gottlieb wrote in The New Yorker in 2013.

10. A POSTWAR PRODUCTION OF OUR TOWN IN GERMANY WAS SHUT DOWN.

The Christian Science Monitor reported in its February 13, 1946 issue that the Soviet Union had put a stop to a production of Our Town in the Russian sector of Berlin. The play was canceled “on the grounds that the drama is too depressing and could inspire a German suicide wave,” the magazine stated.

Wilder’s sister Isabel later offered an alternate explanation. “[Our Town] was the first foreign play to be done in Berlin shortly after the occupation. The Russian authorities stopped it in three days. Rumor gave the reason that it was ‘unsuitable for the Germans so soon—too democratic.'”

11. THE PLAY’S GENRE IS HARD TO PIN DOWN.

In theater, comedies often end in weddings, while dramas frequently end in death. Our Town offered a bit of both and in an introspective manner that celebrates the grace and frustrations common to the human experience. In 1956, theater historian Arthur Ballet and playwright George Stephens had an academic debate about whether the play was a tragedy. Ballet declared it a “great American drama” because the Stage Manager is born from the Greek chorus tradition. But Stephens rejected this categorization, calling it “gentle nostalgia or, to put it another way, sentimental romanticism.”

12. WILDER BRIEFLY APPEARED IN OUR TOWN.

For two weeks in its original 1938 run on Broadway, Wilder himself played the role of the Stage Manager, though Frank Craven originated the role in its debut production. The actor of stage and screen appeared in a long list of movies, including the Will Rogers drama State Fair (1933), the Howard Hawks-helmed adventure Barbary Coast (1935), and the horror movie Son of Dracula (1943). However, Craven is best remembered for his portrayal as Our Town‘s Stage Manager, a role he reprised in the 1940 film adaptation.

13. OUR TOWN CONTINUED TO WIN AWARDS.

Broadway revivals were mounted in 1944, 1969, 1988, and 2002. The 1988 revival starring Eric Stoltz and Penelope Anne Miller as George and Emily garnered the most acclaim. It earned five Tony nominations, including those for Best Featured Actor (Stoltz), Featured Actress in a Play (Miller), Costume Design, Direction of a Play, and Revival, as well as four Drama Desk nods for Outstanding Featured Actor in a Play (Stoltz), Featured Actress in a Play (Miller), Lighting Design, and Revival. This production won the Tony and Drama Desk awards in the Best Revival category.

14. OUR TOWN GOT A HAPPY ENDING WHEN IT WENT HOLLYWOOD.

The play’s first film adaptation hit theaters in the spring of 1940. Martha Scott, who made her Broadway debut originating the role of Emily Webb, reprised the part in this movie. Major changes were made in the film version, like the inclusion of sets and props—but most noticeably, Emily lives, turning the play’s third act into a dream sequence. Perhaps surprisingly, Wilder argued for the change.

He wrote to Sol Lesser, the film’s producer, “Emily should live … in a movie you see the people so close ‘to’ that a different relation is established. In the theatre, they are halfway abstractions in an allegory, in the movie they are very concrete … It is disproportionately cruel that she die. Let her live.”

15. ITS SIMPLE STAGING HAS HELPED MAKE OUR TOWN A VERY POPULAR REVIVAL.

Thanks to the play’s minimal stage design requirements, community theaters and high school drama clubs can take on this American classic with meager budgets. And they often have. “Our Town goes on and on and on and on. Is there a high school in America that hasn’t staged it?” Gottlieb wondered in The New Yorker. Its accessibility, along with the play’s universal themes about love and mortality, have made Wilder’s contemplative classic a staple for new generations of theater lovers.

0 notes

Text

Helen Dunmore

how come I did not know this

Helen Dunmore obituary

Poet and novelist with a flair for reinvention and making history human

Kate Kellaway

The writer Helen Dunmore, who has died aged 64 of cancer, seldom made herself her subject. The author of 12 novels, three books of short stories, numerous books for young adults and children and 11 collections of poetry, she was remarkable in that, although she made an impression from the start, her career evolved in unexpected ways.

As she grew older, she knew what to shed, how to travel light, how to pursue questions that occupied her single-mindedly – as if sweeping a room clear of dust. In her 20s, she had written a couple of unpublished autobiographical novels and would imply that these belonged in the bottom drawer – mere staging posts on the road to becoming a novelist, a way of getting herself out of the picture.

Helen Dunmore: my moment of inspiration on the operating table

Read more

In an age of self-involvement, Dunmore never wrote a memoir. In an age of intrusive interviews, she kept journalists at a kindly distance. She lived in Cliftonwood, Bristol – the setting for her superb and poignant last novel, Birdcage Walk (2017). She knew she was dying only at the editing stage but suggested, in an afterword, that she must have known subliminally because the novel was “full of a sharper light, rather as a landscape becomes brilliantly distinct in the last sunlight before a storm”. The story is of an 18th-century property developer and his wife, and set at the time of the French revolution, but in Bristol. Dunmore’s workplace was a flat on Bristol’s northern slopes from which, eight floors up, she could see the city below: “I find the view beautiful and absorbing,” she wrote in 2016 in a rare first-person piece for the Guardian, “but not a distraction.”

She was – first and last – a poet. Her first collection, The Apple Fall, was published when she was 30, her last, Inside the Wave, in April this year. It was her 1988 collection, The Raw Garden, that established her, celebrating nature without flattery. She had an eye for the imperfection that makes beauty interesting (she read Wild Strawberries, a poem from this collection, beautifully on Radio 3’s The Verb in February this year). In 2007, her poem The Malarkey, submitted anonymously, won the National Poetry Competition. It was, she said, about “what time takes away and how we take time for granted”. Her last collection is her most spare and moving. Inside the Wave is smooth as a sea pebble and liminal – poised between life and death.

It would have been natural to predict, given Dunmore’s talent, that a poet is what she would exclusively remain. But she started submitting stories to magazines – collected as Love of Fat Men (1997) – and once said that, in prose, she was “taking the brakes off”. In 1993, aged 40, she published Zennor in Darkness, a debut novel that won the McKitterick prize and was described by John le Carré as “beautiful but inspiring”. What emerged was a gift for making history human. This bold novel placed literary figures (DH Lawrence and his German wife, Frieda, thought to be spies by Cornish locals) alongside invented characters without strain. It read authoritatively – almost as if penned by Lawrence – but it was Dunmore’s understanding of what it must have been like to lose sons and lovers in the first world war that made it memorable.

In The Siege (2001), shortlisted for the Orange prize and the Whitbread, she went further. She described the siege of Leningrad, focusing on the frailty of a city and the resilience of its citizens facing and, in some cases, outfacing extremity. This was followed by The Betrayal (2010, longlisted for the Booker) about postwar Russia. In The Greatcoat (2012), a ghost story for Hammer, she focused on the aftermath of the second world war and in The Lie (2014), it was the first world war’s aftermath that detained her.

It takes imaginative courage (as well as research) to envisage the ways in which historical events wreck lives. As a novelist, courage was Dunmore’s defining quality – part of her emotional intelligence. She was famous for her generosity to other writers. She taught on Arvon Foundation courses, set up a Bristol poetry group, worked on the management committee of the Society of Authors and was, for a year, its chair. She was a trustee of the Royal Literary Fund.

Other subjects and settings – aside from war – recurred in her work. Cornwalloften featured. Dunmore had, for 40 years, a family house in St Ives and loved the county. The sea (often seen from Porthmeor beach) captivated her – her conversation with it, in prose and poetry, ending only with her death. Her ability to write sensually about food was much praised. Winter was her season (A Spell of Winter won the Orange prize in 1996, its inaugural year), although her winter’s tales were thawed by her warmth as a writer. She was a qualified teacher and time spent teaching in Finland (1973-75) used to be offered as the explanation of how she became a connoisseur of the cold.

Helen Dunmore: facing mortality and what we leave behind

Read more

Dunmore was born in Beverley, Yorkshire, the second of four children of Betty (nee Smith) and Maurice Dunmore. She grew up in a haphazard, bookish household. Her father managed industrial firms but loved poetry and Dunmore learned many rhymes, hymns and ballads during a peripatetic childhood. She attended Nottingham high school, then studied English at York University (1970-73) where she became entranced by the Russian poets, especially Osip Mandelstam (she was a lifelong Russianist). Her critical work included studies of Emily Brontë’s poetry, DH Lawrence’s stories and Virginia Woolf’s relationships with women. She became a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1997.

She had a rapport with children, as her unpatronising books for younger readers show. Her Ingo series was magical: she made mermaids and mermen seem more real, less provisional, than humans. Dunmore’s readers will not be surprised to learn she loved gardening – she knew her wild flowers. She was a plucky swimmer, venturing into the sea on cold days in a wetsuit. She loved art, buying as much as she could afford and enjoying collaborations with artists and musicians.

But, however adept at living well, she was undeceived about life’s difficulties. She once said the “safe” life was the exception. And she was sensitive to the subject of mortality. In her marvellous novel Mourning Ruby (2003), grief was an impostor against whom there was no defence. Each chapter began with an elegiac quotation borrowed from another writer. The epilogue opened with a poem of her own:

A field is enough to spend a life in.

Harrow, granite and mattress springs,

shards and bones, turquoise droppings

from pigeons that gorge on nightshade berries,

a charm of goldfinch, a flight of linnets,

fieldfare and January redwing

venturing westward in the dusk,

all are folded in the dark of the field,

all are folded into the dark of the field

and need more days

to paint them than life gives.

She married Frank Charnley, a lawyer, in 1980. He survives her, along with her son, Patrick, daughter, Tess, stepson, Ollie, and grandchildren, Hugo, Amber and Blake.

• Helen Dunmore, poet and novelist, born 12 December 1952; died 5 June 2017

0 notes

Text

TRACES OF SELF-EXILE

BY MIMI ZEIGER

A new biography of James Rose explores his difficult brilliance.

FROM THE AUGUST 2017 ISSUE OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE MAGAZINE.

“Words! Can we ever untangle them?” reads James Rose’s opening salvo in Pencil Points. Appearing in the definitive journal of modernist design thought, the landscape designer’s 1939 essay rejects preconceived ideas of formal or informal design and makes the case for an organic and materials-based approach—an argument approaching revelation at a time when Beaux-Arts methodologies held sway.

Reading the text today, Rose’s words cut through the decades, carrying with them equal doses of wit, creativity, and frustration with the status quo. An uncompromising designer from his time in and out of Harvard (he was expelled in 1937, later returned but never graduated) to his death in 1991, Rose is the subject of the latest volume of the Masters of Modern Landscape Design series published in association with the Library of American Landscape History and the University of Georgia Press. It’s the first biography dedicated to the landscape architect, who although a prolific writer throughout his career and author of four of his own books, has yet to receive the kind of canonical recognition bestowed on his Harvard classmates Garrett Eckbo and Dan Kiley.

As director of the James Rose Center for Landscape Architectural Research and Design—a nonprofit located at Rose’s Ridgewood, New Jersey, home—the book’s author, Dean Cardasis, FASLA, is well-placed to untangle the competing forces of Rose’s career. Few of Rose’s works survive in their original form, and a spare eight are presented as illustrated case studies—a fraction of the more than 80 projects produced in his lifetime. Much of the book is devoted to advocating for Rose’s achievements while trying to account for the designer’s disillusionment with the culture of postwar landscape architecture and his eventual self-imposed exile to suburban New Jersey. Although these two threads are not in opposition, they do place a strain on the narrative, suggesting a portrait of a man whose increasing radicalism over the course of decades—from modernism to ad hoc material sensibilities to environmentalism—contributed to his own isolation. “He was a rebel’s rebel from the start, an incisive critic destined to follow his own path,” Cardasis says.

Early in the prologue for the book, Cardasis describes his first encounter with a 76-year-old Rose (just a couple years before his death). The passage is clearly loving, but also disconcerting. A disheveled and mismatched Rose steps out of a “rusty, egg-yolk-colored 1970s VW van,” and Cardasis writes: “An incredibly long, almost wizard-like straw hat grazed his shoulders and shaded his face. As he looked up I could see he was wearing glasses, but one frame was empty, and the remaining one held a tinted sunglass lens. In that instant I had my first silent lesson from the iconoclastic modern landscape architect James Rose: ‘Have no preconceptions.’”

A view nearly without boundaries from inside to out at Rose’s house in Ridgewood, New Jersey. From Progressive Architecture (1954).

It’s from this point that a revolutionary must be nudged into the historical fold. The task isn’t easy, though it is most successful early in Rose’s biography. Cardasis, unpacking Rose’s interest in modernism, finds parallels in the spare poetry of William Carlos Williams and the easy spatial flow of Rudolph Schindler’s Kings Road house, which serves as a precedent for Rose’s home in Ridgewood. In both projects, the use of outdoor rooms and landscape features illustrates Rose’s maxim that “landscape design falls somewhere between architecture and sculpture.”

Indeed, Rose’s own writings referenced modern artists such as Pablo Picasso and the Russian constructivist Naum Gabo. Rose even wrote that a Georges Braque still life and Kurt Schwitters’s Rubbish Construction are “interesting suggestions for gardens.” The book describes that fascination with collage and assemblage, tracking it through Rose’s work, where it appears initially in the model Rose made of his future home while in the navy, the materials scavenged from around his military station, or in the scrap metal fountains he improvised in the 1960s and 1970s. The author continues this line of argument to suggest Rose’s use of recycled railroad ties and asphalt—used for the steps and terraces of the Averett Garden and House in Columbus, Georgia (1959)—as an example of Rose’s affinity for “found objects.”

But later, as modernism gave way to countercultural influences, it is harder to pin Rose down. Cardasis chronicles the designer’s withdrawal from mainstream landscape architecture and, more generally, American culture, citing a growing aversion to the impact of postwar suburban development on the existing landscape as the cause. He quotes from Rose’s 1958 book Creative Gardens as evidence: “The recipe is simple: first, spoil the land by slicing it in particles that will bring the most dollars, add any house that has sufficient selling gimmicks to each slice, and garnish with ‘landscaping.’”

Perhaps as a respite, Rose began traveling regularly to Japan and eventually began practicing Zen Buddhism. “He went to Japan in 1960, and that started a love affair with the country that went on for his whole life,” Cardasis told me by phone. “Rose found inspiration in the Eastern tradition, especially in the attitudes to the natural world.”

Rose and a carpenter confer during roof garden construction in 1970. Courtesy James Rose Center.

Given Rose’s then-radical understanding of landscape architecture as an integration of spatial and natural conditions, the banal blanketing of suburban conventions across the United States would surely account for his retreat; however, Rose was not alone in his critique. Other writers, designers, and artists of the period shared his early environmentalist stirrings, so it is strange to find few references, especially given the wealth of parallels drawn in support of Rose’s embrace of modernism. The book makes brief and tantalizing allusion to significant countercultural figures: Timothy Leary (Rose apparently dropped LSD with him but “wondered what the fuss was all about”) and Alan Watts (Rose studied with him but then renounced Watts’s teachings). It would seem that his cantankerous personality instigated isolation as much as his ideology.

The biography doesn’t hide that Rose was gay, though the narrative doesn’t put emphasis on the designer’s sexuality as an overt source of his outsiderness. “As you know, Rose lived in a time when being gay was extremely difficult, and I can only imagine how that influenced his life and work,” Cardasis said in an e-mail. “Because of this and in deference to his expressed wishes not to belabor the fact, I did not explore the issue further than a simple reference to his sexuality in the book. More (or less), I thought, would be inappropriate.” The result of this tact, however, is that the biography seems a bit closeted—the queerness in Rose’s methods left for others to explore at a later time.

Despite his iconoclasm, there were moments that suggest possible connections between Rose and other practitioners. For the 1960 issue of Progressive Architecture, the editors asked Rose, Lawrence Halprin, and Karl Linn—the environmentalist, activist, and pioneer of urban gardening—to review each other’s work. Rose’s Macht Garden and House in Baltimore from 1956 was subject to strong critique by the others for its expressiveness, particularly what was termed the “incessant” angled terraces. While Cardasis characterizes the grouping of designers as something the magazine “cooked up,” as if it were a bit of a stunt, there was clearly editorial intent here to make alignments between three landscape architects operating outside the conventional mien, with anticipatory ties to social and ecological movements. As Rose’s work reenters the canon, more research is needed to better situate it historically.

Eleanore Pettersen, the architect for the Paley house, brought Rose on to design the garden. The site was a rocky, sloping woodland. Drawn by R. Hruby (1994); Courtesy James Rose Center.

Did Rose deliberately push away his contemporaries and potential allies? It’s likely. He was never shy about getting into arguments with clients, but he also had his defenders. In the 1970s and 1980s, he collaborated with the architect Eleanore Pettersen on some 30 projects. In addition to sharing his design sensibilities in terms of fluid relationships between inside and outside, she often acted as Rose’s advocate, especially when he put off clients and building officials. There seems to be more to explore here between the iconoclastic designer and his champion. Pettersen apprenticed with Frank Lloyd Wright and was the first woman architect to start her own practice in New Jersey in the early 1950s. One can’t help but wonder why someone who probably had to fight against social norms throughout her career would willingly stand up for the volatile Rose. The answer in the biography points again to Rose’s possessing an irascible genius, the nature of which compelled others to be forbearing. This was a period of his practice when he would meditate in the morning and then go build improvisationally on site without drawings. Pettersen, interviewed in 1992, is quoted in the biography simply telling clients: “It will be worth it.”

Justification for that value is elusive and impressionistic. Because of that lack of documentation, the James Rose foundation has a limited record of projects to refer to for backup. Although he published regularly early in his career, writing essays and three books from the 1930s through the 1960s, Rose’s pace slowed afterward, and he published his last book, The Heavenly Environment: A Landscape Drama in Three Acts with a Backstage Interlude, in 1987. Ultimately, it is Rose’s own home, now the James Rose Center for Landscape Architectural Research and Design, that serves as an interpretative text for understanding the work: handmade, iterative, and as quixotic as its author, with courtyards, roof gardens, and a Zendo, each in various states of repair.

The biography puts forth a belief that understanding Rose’s later oeuvre comes mostly through understanding his singular methodology. Words are left behind to untangle. “You can feel it when you go to the site,” Cardasis says. “As you move through, the garden seems as if it could go on forever. There was no plan as an approach; he just moved through, adjusting things to make people aware of their connectedness to things larger than themselves.”

Mimi Zeiger is a critic and curator based in Los Angeles.

from Landscape Architecture Magazine https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2017/08/03/traces-of-self-exile/

0 notes