#patapsco

Text

Mayday from the Dali. 🚢 ⚡️🌉🆘🛟🟧🟨🟦🟥

#Baltimore#baltimore maryland#baltimore md#Baltimore bridge#dali#global shipping#shipping container#shipping company#tugboat#pop art#folk art#Francis Scott key#oil and gas#world news#childrens book illustration#construction crew#mayday#sos#big boat#ships#patapsco River#patapsco#cargo ship#super tanker#street art#Francis Scott key bridge#bridge collapse#suspension bridge#contemporary art#basquiat

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

patapsco river

#patapsco river#patapsco#hiking#river#baltimore#maryland#me#mine#pink hair#queer#vanlife#road trip#travel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Patapsco Woods, Maryland. Pentax 645, 45mm Free-Lens'd. Kodak Portra 400NC. NIK

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse - Baltimore, Maryland by Kevin B. Moore

#2024#baltimore#bridge#collapse#disaster#fort mchenry#ft mchenry#key bridge#dali#coastguard#boat#patapsco#flickr

0 notes

Text

youtube

Baltimore Maryland Francis Scott Key Bridge Collapses - Struck By Singapore Cargo Ship

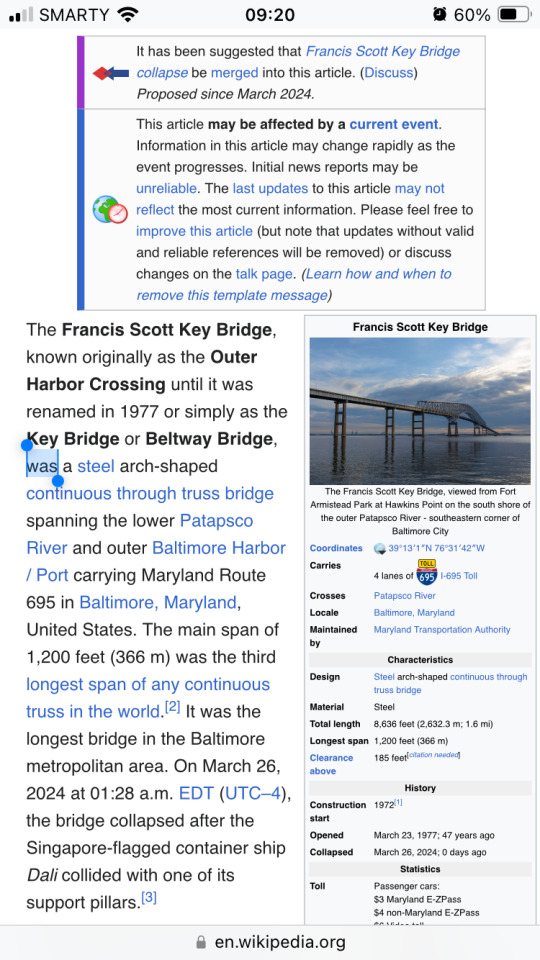

Around 1:30 AM on March 26, 2024, a large cargo ship struck one of the support columns of the 1.6-mile-long Francis Scott Key Bridge, causing the bridge to collapse.

Several vehicles, including one as large as a tractor-trailer, were on the bridge at the time and plunged into the Patapsco River below.

Multiple people are unaccounted for as of now.

The cargo ship involved was the Singapore-flagged vessel Dali, which had just departed the Port of Baltimore when the incident occurred.

Maryland Governor Wes Moore has declared a state of emergency, and the Biden administration is working to deploy federal resources to assist with the response.

The Francis Scott Key Bridge is a vital artery for East Coast shipping, as it connects the Port of Baltimore to the surrounding highway network. The port handled over 84 million tons of cargo in 2023.

The collapse of this major bridge is expected to have significant impacts on transportation and commerce in the Baltimore region until repairs can be made.

#breakingnews#maryland#bridge#collapse#baltimore#keybridge#baltimorebridge#news#francisscottkeybridge#francisscottkey#cargoship#viral#trending#breaking#Patapsco#Patapscoriver#bglw#Youtube

0 notes

Text

#baltimore#baltimore town#patapsco#john adams#wordpress#2016#internet archive#revolutionary war#american revolution

1 note

·

View note

Text

ice shapes at cascade falls

0 notes

Photo

Remember to give #ReimagineMiddleBranch your feedback this week, and check out these local events! #parks #transitequity #Baltimorenonprofits Repost from @reimaginemiddlebranch • No need to worry if you missed the public information sessions last week. Head to our website to check out the draft Reimagine Middle Branch Plan we presented during the December 5th and 6th public information sessions. You may also share your feedback on the Plan! Our feedback form will be open through December 23, 2022. https://www.reimaginemb.com/plan. After viewing the Plan feel free to browse through our website and learn more about the RMB team's vision and dedication to community equity. #MiddleBranch #SouthBaltimore #Community #Patapsco https://www.instagram.com/p/CmaHD4lJizc/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#reimaginemiddlebranch#parks#transitequity#baltimorenonprofits#middlebranch#southbaltimore#community#patapsco

0 notes

Text

Today in a freak accident a container ship leaving the Port of Baltimore struck a support column for the 1.6 mile long Francis Scott Key Bridge causing enough damage to collapse most of the bridge in seconds.

The skyline of Baltimore City will never look the same again

Francis Scott Key Bridge (1977-2024)

Patapsco River, Baltimore, Maryland

#key bridge#francis scott key#francis scott key bridge#bridge#disaster#baltimore#baltimore city#patapsco river#accident#charm city#bmore

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holy shit.

The whole bloody thing is in the water!

Got hit by a massive container ship.

Fucking hell.

I hope nobody was on the damn thing when it collapsed.

Look at it!

It’s GONE!

Fuck.

What’s that?

They already changed the wording on its Wikipedia page?

Jesus Christ wikipedia!

You fuckers really do work fast!

Oh my GOD!

I’m not trying to sensationalise this btw.

I just wasn’t expecting it.

I’m not anticipating such incidents like some ghastly disaster-worshipping ghoul with issues.

I just hope nobody was hurt or killed.

I also worry that the conspiracy nuts will try saying it was faked or some crap. Fuck that shit!

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#news#maryland#bridge#bridges#bridge collapse#crash#cargo ship#what#fucking hell#wikipedia#Baltimore#river#Francis Scott key bridge#patapsco river#beltway bridge#key bridge#Baltimore harbour#container ship#container shipping#editors#bloody hell#dali#singapore#disaster#shitshow#maersk

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avalon area; Patapsco State Park 🌳

#patapsco#patapsco river#patapsco state park#baltimore#maryland#waterfall#waterfalls#travel#hiking#camping#vanlife#travel with me

0 notes

Text

Mosby at Patapsco Woods, Maryland. Nikon FM, 180mm. Fujichrome Provia 100.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Buzzard's Rock Rail Bridge

#patapsco valley state park#maryland#cantonsville#landscape#infrared#590nm#false color#august#around dc#my work#photography

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone who lives locally keeps putting these grandfather clocks in the woods. People are stumbling upon them on hikes. This is off of Rockhaven trail in Patapsco State Park. We have no idea who puts them there, how they get them up there and also why. People think it's a call out to Vecna in Stranger Things but I don't know! It's so funny. The mystery continues.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

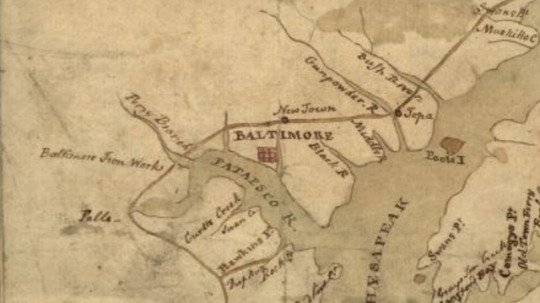

A "dull place" on the Patapsco: Baltimore and the Marr Brothers

In 1776, Baltimore’s population was just over 6,000. This zoomed-in version of a map, courtesy of the Library of Congress, shows how Baltimore was portrayed in 1776.

In May 1776, the Revolution had been raging for almost a year with skirmishes between the British imperial army and the rag-tag revolutionaries. William Marr, probably with his brothers Nicholas and James, enlisted in the Continental Army in Capt. Nathaniel Ramsey’s Fifth Company, a section of the First Maryland Regiment, at Whetstone Point. [1] It was not uncommon for multiple men of the same immediate family to enlist in the Revolutionary War. Many company members were young and residents from the Baltimore area. The Fifth Company included the Marr brothers at Whetstone Point, fortified with 38 cannons and earthworks, two miles below Baltimore, to defend it from British attack. [2] They were joined by Daniel Bowie’s Fourth Company and Samuel Smith’s Eighth Company, as we have noted on this blog in the past. The Marr brothers and members of the three companies of the First Maryland Regiment would have seen a Baltimore that few of us can imagine today. This article is the beginning of a series about Baltimore.

Reposted from Academia.edu and my History Hermann WordPress blog. I originally wrote this when I was working for the Maryland State Archives on the Finding the Maryland 400 project.

In 1776, Baltimore was a small, pre-industrial town on the Patapsco River. It was officially called Baltimore Town until a city charter was received in 1797. [3] The Revolution caused difficulties by ending trade of exports such as wheat, flour, and tobacco with the British West Indies, but due to the war, Baltimore still grew economically and by population beyond 6,000 residents. [4] John Adams, in his stay in late 1776 and early 1777 as part of the Continental Congress, described the town as “very pretty” with revolutionary sentiments, but having dirty, mirey, and foul streets, a “monstrous price of things,” unhealthy air and a “dull place” not even worth defending from the British. [5] Still, Baltimore Town was a bustling and growing commercial port with a job market open to immigrants containing more than 500 dwellings. [6]

Baltimore Town was not as big as Philadelphia, in terms of population. However, the seventy-four enlisted soldiers in the Fifth Company would have seen people of varying backgrounds. There were people from many trades ranging from blacksmiths, shipbuilders at Fells Point, cabinetmakers, bricklayers, shoemakers, among others. [7] Many of these local artisans supplied common amenities and engaged in craft services in Baltimore and neighboring counties, working in a town economy “dominated by commerce.” [8]

Many of these craftspeople relied on unpaid labor such as indentured servants, mostly comprised of male English convicts, thousands of whom were trafficked into the Chesapeake Bay from the early 1700s up until 1776. [9] However, convict trade was brought to a halt due to ending of trade between Britain and colonial America as a result of the beginning of the Revolution. The enlistment of servants to the Continental Army created a labor shortage addressed by an increase of slave importation by master craftspeople. [10] At the time, others entering Baltimore included those of a “middling sort,” German immigrants, and Irish immigrants. [11] In describing Baltimore, John Adams once said that there were a few planters and farmers, who were also merchants, with lands cultivated and trades exercised by convicts and enslaved Blacks. [12] He further described these planters and farmers as having “little public spirit” as they held their enslaved Blacks and convicts “in contempt” and thought of themselves “a distinct order of beings.” [13] It is possible Adams thought lowly of these planters and farmers because they were not contributing to the revolutionary cause as much as he wanted. Still, the attitudes and actions of the planters and farmers was not unique to Baltimore.

Throughout and after the war, Baltimore Town continued to expand. Evidence suggests the Marr brothers likely settled in the Baltimore area, among other surviving soldiers. Meanwhile, Baltimore Town continued to grow by population and export of commodities, such as wheat, although there were price increases, and became an important market. [14] Despite increases in trade and availability of agricultural products, many of the tradespeople could not afford to become property owners as the town was building its unique identity. [15] As 1800 approached and Baltimore developed into more of a maritime city, the town continued to change demographically. [16]

– Burkely Hermann, Maryland Society of the Sons of American Revolution Research Fellow, 2016

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

Notes

[1] National Archives, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, NARA M804, Record Group 15, Roll 1631, William Marr, Pension number W. 3838. courtesy of fold3.com; Order to give back pay of Nicholas Marr, William Marr’s brother, to Lewis Lee. MdHR 19970-05-01-07 [MSA S997-5-7, 1/7/3/11].

[2] Neal A. Brooks and Eric G. Rockel. A History of Baltimore County. Towson: Friends of the Towson Library, 1979. pp. 85, 101; Richard C. Medford. Book Review: ‘Mirror of Americans,’ Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. XXXIX, March 1949, no. 1. pp. 90; S. Synthes Bradford. ‘In Fort McHenry 1814: The outworks in 1814,’ Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. 52, no. 2, June 1959. pp. 188-189, 191; Christopher T. George. ‘Book Review of Fort McHenry,’ Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. 9, no. 6, 1996. pp. 224; Hamilton Owens. Baltimore on the Chesapeake. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Company, 1991. pp. 85. Years later, in 1814, Whetstone Point, like during the during the Revolution, then the site of Fort McHenry (‘Notes and queries: The President visits Maryland, 1817,’ Maryland Historical Magazine, Vol. XLIX, June 1954, no. 2. pp. 168), held off the British destruction of the “”very pretty town.”

[3] Charles Francis Adams. Familiar Letters of John Adams and his wife Abigail Adams During the Revolution with a memoir of Mrs. Adams. New York: Hund and Houghton, 1876. pp. 296; Charles G. Steffen, The Mechanics of Baltimore: Workers and Politics in the Age of Revolution, 1763-1812. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1984. pp. 3; Kathryn Allamong Jacob. ‘The Women’s Lot in Baltimore Town: 1729-1797.’ Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. 71, no. 3, fall 1976. pp. 263.

[4] Edward J. Perkins. The Economy of Colonial America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1988, 135; Steffen, The Mechanics of Baltimore, 4; Matson, Cathy. “The Atlantic Economy in an Era of Revolutions: An Introduction.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 62, no. 3 (2005): 360; US Census. A Century of population growth from the first census to the twelfth. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909. pp. 30; Paul Kent Walker, ‘Business and commerce in Baltimore on the eve of independence,’ 296; Jacob Harry Hollander. The Financial History of Baltimore vol. 20. Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1899. pp. 17; Arthur M. Schlesinger. ‘Maryland’s share in the last intercontinental war.’ Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. VIII June 1912, no. 2. pp. 125; Sherry H. Olson. Baltimore: The Building of an American City. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997. pp. 15; Henry C. Ward. The War for Independence and Transformation of American Society: War and Society in the United States, 1775-85. New York: Routledge, 1999. pp. 152.

[5] Owens, Baltimore on the Chesapeake, 110; Charles Francis Adams. The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States Vol. III. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851. pp. 25, 198; Tina M. Sheller. ‘Freeman, Servants, and Slaves: Artisans and the craft structure of Revolutionary Baltimore Town.’ American Artisans: Crafting Social Identity, 1750-1830 (ed. Howard C. Rock, Paul A. Gilje and Robert Asher). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995. pp. 26; Adams, Familiar Letters of John Adams and his wife Abigail Adams During the Revolution with a memoir of Mrs. Adams, 237; Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 18 February 1777. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society; Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 7 March 1777. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society; John Adams diary 28, 6 February – 21 November 1777. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society (entry for Feb. 9, 1777); Jacob, ‘The Women’s Lot in Baltimore Town: 1729-1797,’ 291.

[6] Lawrence C. Wroth, ‘A Maryland Merchant and his friends in 1750,’ Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. VI, Sept. 1911, no. 3. pp. 215, 219; Sheller, ‘Freeman, Servants, and Slaves,’ 18; George W. Howard. The Monumental City, Its Past History and Present Resources. Baltimore: J.D. Ehlers and Co., 1873. pp. 20.

[7] Daniels, Christine. “”WANTED: A Blacksmith Who Understands Plantation Work”: Artisans in Maryland, 1700-1810.” The William and Mary Quarterly 50, no. 4 (1993): 760-761, 766; Mariana L.R. Darlas. Black Townsmen: Urban Slavery and Freedom in the Eighteenth Century Americas. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008. pp. 90; Adams, Familiar Letters of John Adams and his wife Abigail Adams During the Revolution with a memoir of Mrs. Adams, 18; Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 10 February 1777. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society; Sheller, ‘Freeman, Servants, and Slaves: Artisans and the craft structure of Revolutionary Baltimore Town,’ 18, 25.

[8] Sheller, ‘Freeman, Servants, and Slaves: Artisans and the craft structure of Revolutionary Baltimore Town,’ 19-20.

[9] Daniels, ‘Artisans in Maryland, 1700-1810,’ 752; Morgan, Kenneth. “The Organization of the Convict Trade to Maryland: Stevenson, Randolph and Cheston, 1768-1775.” The William and Mary Quarterly 42, no. 2 (1985): 203, 205, 211, 217; M. Darlas. Black Townsmen: Urban Slavery and Freedom in Eighteenth Century Americas. pp. 40-41.

[10] Morgan, “The Organization of the Convict Trade to Maryland: Stevenson, Randolph and Cheston, 1768-1775,” 202, 222; Darlas, Black Townsmen, 75; Ward, The War for Independence and Transformation of American Society, 215; Sheller, ‘Freeman, Servants, and Slaves: Artisans and the craft structure of Revolutionary Baltimore Town,’ 27.

[11] Eugene Irving McCormac. White servitude in Maryland, 1634-1820. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1902. pp. 32; Middleton, Simon, and Smith Billy G. “Class and Early America: An Introduction.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 63, no. 2 (2006): 219; Allan Kulikoff. Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1986. pp. 425; Olson, Baltimore, 15.

[12] John Adams diary 28, 6 February – 21 November 1777 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society (entry for Feb. 23, 1777).

[13] John Adams diary 28, 6 February – 21 November 1777 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society (entry for Feb. 28, 1777).

[14] Brooks and Rockel, A History of Baltimore County, 107; Hunter, Brooke. “Wheat, War, and the American Economy during the Age of Revolution.” The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 62, no. 3 (2005): 510, 516, 522, 524; Cometti, Elizabeth. “Inflation in Revolutionary Maryland.” The William and Mary Quarterly 8, no. 2 (1951): 230; George W. Howard. The Monumental City, Its Past History and Present Resources. Baltimore: J.D. Ehlers and Co., 1873. pp. 25; Steffen, The Mechanics of Baltimore, 10-11; Olson, Baltimore, 10; Shammas, Carole. “The Space Problem in Early United States Cities.” The William and Mary Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2000): 505-506, 509.

[15] Steffen, Charles G. “Changes in the Organization of Artisan Production in Baltimore, 1790 to 1820.” The William and Mary Quarterly 36, no. 1 (1979): 103, 113.

[16] Mark N. Ozer. Baltimore: Persons and Places. Baltimore: Garden Publishing, 2013. pp. 37; Olson, Baltimore, 10.

#patapsco#baltimore#revolutionary war#maryland 400#continental army#maryland#baltimore county#baltimore md#farmers#continental congress#john adams

0 notes

Text

Fuck I'm So glad we didnt go anywhere this spring break. That bridge is like....so commonly used good lord.

My Cousin uses that bridge (she works at amazon) She took off that day but christ thats such a lucky break.

#Personal#Baltimore#bridge collapse#baltimore bridge collapse#patapsco river#<<<<thats so close to me thats literally my port

3 notes

·

View notes