#pat garrett and billy the kid

Text

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

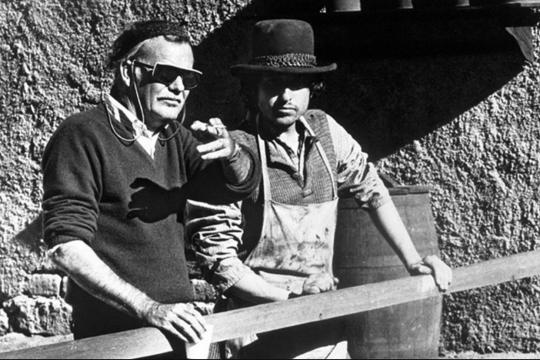

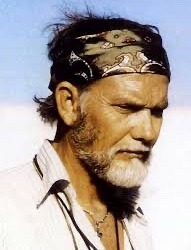

“ James Coburn and director Sam Peckinpah on the set of the film "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid" (1973) “

Source: @GroovyHistory

#vintage#glamour#celebrity#james coburn#sam peckinpah#legends#icons#movie stars#tv stars#director#movies#old hollywood#pat garrett and billy the kid#1970s#behind the scenes

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

december 18, 1972

Shooting begins for Bob Dylan's part in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

On April 7, 2013, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid was screened Festival Frontieres.

#pat garrett and billy the kid#sam peckinpah#revisionist western#western movies#tcm underground#action movies#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#cult movies#portrait#cult film#james coburn#bob dylan

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Because in the BBC audio play “The Adventures of Pat Garrett And Billy the Kid (Deceased) Pat mentions a wife.

Nancy: Where’s your wife now?

Pat: Home...waiting for me.

Nancy: You hold her in some affection?

Pat: You have no idea...

So here’s my self insert wife for Pat Garrett! Sarah Jane Marsden(Marsden a nod to one of my favorite game series: Red Dead Redemption’s John Marsden)

I gave her the straight and red hair of Sean Gilder’s real life wife, the beautiful Robin Weaver! <3 <3 <3

Helped creating her by my dearest @ariel-seagull-wings

The outfit in the first panel was given to me by the dear @professorlehnsherr-almashy based on his period clothing books! Sarah Jane’s working clothes and her Sunday best!

@superkingofpriderock @ailendolin @captain-dad

#pat garrett and billy the kid#the adventures of pat garrett and billy the kid deceased#my self inserts#my self insert art#because it's sean gilder#sean gilder's no. 1 fangirl

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

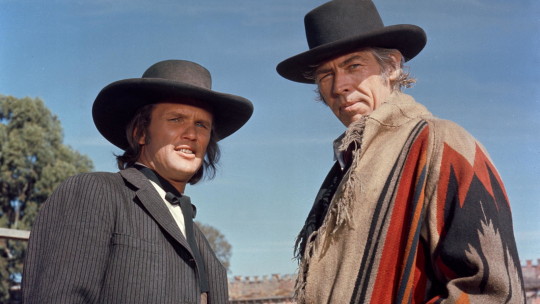

James Coburn and Kris Kristofferson in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Sam Peckinpah, 1973)

Cast: James Coburn, Kris Kristofferson, Bob Dylan, Richard Jaeckel, Slim Pickens, Katy Jurado, Chill Wills, Barry Sullivan, Jason Robards, R.G. Armstrong, Luke Askew, John Beck, Jack Elam, Rita Coolidge, Charles Martin Smith, Harry Dean Stanton. Screenplay: Rudy Wurlitzer. Cinematography: John Coquillon. Music: Bob Dylan.

With its laid-back pace punctuated by moments of violence, not to mention its soundtrack by Bob Dylan, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid may be the ultimate stoner Western*. After being mutilated by MGM -- the credits list six film editors -- it was savaged by critics on its first release, but the release on video of Sam Peckinpah's original preview version in 1988 caused a reevaluation of the film, with some now calling it a masterpiece. I wouldn't go that far: To my mind the narrative is still too elliptical and the inspiration -- rewriting a myth -- too commonplace. But it has moments of brilliance that transcend its flaws, such as the beautiful sequence of the death of Sheriff Baker (Slim Pickens), with its fine use of the iconic performers Pickens and Katy Jurado and the underscoring with Dylan's "Knockin' on Heaven's Door." James Coburn, always an underrated actor in his prime, is wonderful as Pat Garrett, and while Kris Kristofferson was never much of an actor, he and Coburn play well against each other. Dylan was no actor, either, but he's used well here as the enigmatic figure who lets himself be known as "Alias," and the scene in which Garrett forces him to read the labels of canned goods while he toys with other members of Billy's gang is nicely done. The gallery of character actors both old (Chill Wills, Jack Elam) and new (Charles Martin Smith, Harry Dean Stanton) is welcome. Its post-censorship era's exploitation of women -- there are an awful lot of bared breasts, though we also get a fleeting butt-shot of Kristofferson -- is overdone, and it certainly wouldn't earn any seal of approval from the American Humane Society after the scene in which live chickens are used for target practice.

*The huge success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969) spawned a lot of movies that took an irreverent look at the legend of the American Old West and were aimed at the younger countercultural audience. Most of them were seen as commentaries on American violence and the quagmire of the Vietnam War. They include such diverse films as Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1970), McCabe & Mrs. Miller (Robert Altman, 1971), The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid (Philip Kaufman, 1972), The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (John Huston, 1972), and Blazing Saddles (Mel Brooks, 1974).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

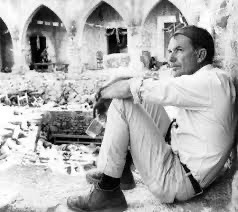

The happiest of birthdays in the afterlife to my other father, Sam Peckinpah! He and his movies mean everything to me!

#sam peckinpah#the wild bunch#cross of iron#the getaway#junior bonner#the deadly companions#pat garrett and billy the kid#the ballad of cable hogue#ride the high coubtry#straw dogs#convoy#killer elite#bring me the head of alfredo garcia#the osterman weekend#filmmaker

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

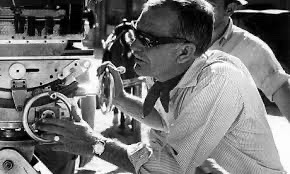

Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973, Sam Peckinpah, USA)

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Another of my Dylan videos “Knockin' On Heaven's Door” - Bob Dylan 1973 (Lyrics)

#youtube#bob dylan#bob dylan knockin' on heaven's door#knockin' on heavens's door#pat garrett and billy the kid#lyrics video

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You killed the boys, Patsy!" "No, you did. If I was with you I would've been one of them."

- Billy the Kid & Pat Garrett, Young Guns II

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (Sam Peckinpah, 1973)

Todos conocéis la historia (o la leyenda); sabéis que Billy va a ser muerto por su antiguo mentor y compañero Pat Garrett, ahora convertido en sheriff. Nadie acude a esta película, pues, a averiguar qué pasó; atrae la idea de asistir, una vez más, como a un rito, a la confrontación mítica de dos visiones divergentes de la supervivencia. Es más el cómo que el qué lo que nos interesa; no es el acontecimiento en sí lo que importa ya, sino su representación, pues queremos descubrir el sentido profundo —no las motivaciones— de la muerte de Billy a manos de Garrett, y la interpretación de Peckinpah nos atañe más que ninguna otra, dado que la amistad tradicional es un tema que le obsesiona (Ride the High Country, Major Dundee, The Wild Bunch). No hay intriga ni «suspense», y Peckinpah no intenta crearlo, pues sería ilógico con un relato cuyo fin y principio son del dominio público. Ni siquiera es una película propiamente narrativa: un argumento tan sabido no precisa entrar en detalles; sobran —por dudosas o innecesarias— las explicaciones, la continuidad, la presentación de los protagonistas. Peckinpah las omite y pasa a exponer limpiamente, desde la primera secuencia, las cartas que va a jugar: un Garrett cansado, vendido a Chisum, sin convicción, con vergüenza y melancolía, trata de disculparse («Es como si los tiempos hubiesen... cambiado»), y Billy, sin reflexionar, con reflejo de adolescente que se niega a aceptar el peso de la realidad y el paso de los años, reafirma su desafío («Los tiempos, tal vez..., pero yo no»). En el fondo, se trata del combate entre dos opciones subjetivas, porque la situación objetiva de Pat y Billy no es tan diferente: ambos, lo reconozcan o no, son supervivientes, desplazados y acosados, y llevan las de perder, porque su hora ha quedado atrás. Y han de destruirse, porque se conocen fraternalmente, porque la existencia del otro constituye un reproche y un recordatorio de la falsedad o insinceridad de su propia postura, porque el más «realista» de los dos ha sido infiel a sí mismo: ha de morir uno, siempre el que se ha resignado menos y, por preservar su autenticidad, se ha convertido en un anacronismo; claro que el otro, en el fondo, morirá también, al menos como persona, si no logra renacer de sus cenizas haciendo suya una nueva causa (como Deke Thornton-Robert Ryan al cierre de Grupo salvaje.) Este drama universal no es privativo del cine —Nido de nobles, de Turgeniev; El reto, de Chejov; El gatopardo, de Lampedusa; The Unvanquished y Flags in the Dust, de Faulkner, lo tratan a su manera— ni del western, pero ha encontrado en este género un terreno propicio, de Duelo al sol y La pradera sin ley, de King Vidor, o Río Rojo, de Hawks, a Centauros del desierto y El hombre que mató a Liberty Valance, de Ford, pasando por Yuma, de Fuller; Hombre del Oeste, de Anthony Mann, y Una trompeta lejana, de Walsh. Pero esta semejanza no sólo demuestra la importancia que tiene el tema para Peckinpah, sino que sirve para resaltar las divergencias que existen entre películas tan claramente emparentadas. Si, en general, el conflicto entre los protagonistas opuestos y complementarios es un reflejo de la situación de guerra civil que atraviesa el país o el territorio en el que evolucionan, en Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid Peckinpah ha despojado el film de todo drama que no sea el enunciado por el título, de modo que su sentido queda más al desnudo que nunca, ya que no son causas externas las que ponen fin a la trayectoria de Billy, sino su propia actitud vital y el rechazo de la alternativa que Pat representa. Se podrá decir, claro, que todo eso estaba ya —tal vez con una resonancia más vasta y compleja (Grupo salvaje y Major Dundee), de forma más discreta (La balada de Cable Hogue) o clásica (Duelo en la alta sierra)— en films anteriores, pero creo que en esos más y menos reside la novedad esencial de Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid: en que este último «western» es ya otra cosa, algo así como la disolución del western, el último coletazo y el estertor agónico —ya disgregado, descarnado, desangrado— del género; de ahí el barroquismo de las composiciones, los juegos de luces al alba y al ocaso y de sombra que cae sobre el color y el paisaje —nubarrones, lluvia suave, árboles retorcidos, llanuras rojas, madera reseca y paredes desconchadas— que dominan los planos exageradamente anchos de este western fantasmagórico y fúnebre, de muerte y desolación; de ahí también el ritmo lento y ceremonioso, aunque entrecortado, majestuosamente dilatado por la dispersión narrativa y la reiteración ritual de las situaciones, como de lánguidos y tristes blues, del que se hace fielmente eco la magistral partitura de Bob Dylan. Es como si el western, antes de ser definitivamente arrinconado y convertido en despojos, se vistiese con sus mejores galas para despedirse, ya moribundo pero aún palpitante. Es el punto final, el acta de defunción; por eso Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid es para mí una de las películas más conmovedoras, acongojantes y lúcidas que se han hecho, la que prefiero de Peckinpah, la que más me emociona de los años 70. Admiración y entusiasmo que pocos comparten, porque Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid es también una obra desconcertante, frustrante por su propia naturaleza: no existe narración, ni casi acción, y muy poca verosimilitud; todo es comentario, reflexión, mito; en una palabra, forma, porque del western lo único que pervive ya son las formas, los signos, la imaginería. Cada plano posee una singular y desgarrada belleza, y su acumulación sucesiva y pausada no hace progresar el relato, sino que amontona patéticos testimonios sobre la decadencia y desintegración de las pandillas, la traición y el abandono, la soledad y la rendición, la violencia insensata y absurda, la aterradora tristeza de cada muerte —que anula, siega, abre un vacío, asola: recordad las de L. Q. Jones, Slim Pickens, Jack Elam, Kris Kristofferson, e imaginad, por su partida solitaria mientras los niños le tiran piedras, la de James Coburn— y la pérdida de sentido de la misma supervivencia.

Publicado en el nº 12 de Casablanca (diciembre de 1981)

0 notes

Text

@hoppkorv, thank you.

Bob Dylan as Alias

Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid

Dir: Sam Peckinpah

#<3#hoppkorv#bob dylan#alias#pat garrett & billy the kid#sam peckinpah#my gifs#my edit#this is for you#you know what you did#and it means a lot

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

tom blyth fishing with daniel webber and alex roe.

#billy the kid#tom blyth#daniel webber#alex roe#pat garrett#william h bonney#jesse evans#cast#fishing#friends

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

july 13, 1973

Bob Dylan releases Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, the soundtrack album for the Sam Peckinpah-directed movie of the same name.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On September 20, 1973 Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid debuted in Australia.

#pat garrett and billy the kid#bob dylan#western movies#revisionist western#revisionist film#cult cinema#fan art#western movie art#weird west#sam peckinpah#new art#new fan art#pen drawing#pen art#western art#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#cult movies#portrait

4 notes

·

View notes