#oldest living vertebrate

Text

i find it so fucking funny how associated cephalopods are to eldritch horror and eldritch abominations and the unknowable universe when like

all of them that i can think of like to 5 years maximum, die immediately after fucking once, and one of the proposed reasons for how smart they are is that Everything In The Ocean Wants To Eat Them

like. theyre being beat out by jellyfish, who do not even have brains, as a significant chunk of jellyfish species can just. turn back the clock. make themselves young again. nbd.

#all the care guide says is 'biomass'#every time i think about cephalopods i start laughing#yeah. hows being the cannibalistic incel species turning out for your sapience?#tell me more about eternity. species who doesnt even live as long as a vampire bat.#let alone vertebrate fish because holy shit way more fish than you realize can easily hit a century in age#to the point where we dont really know the true limit of it#because we keep fishing and eating the oldest and biggest fish

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I recently found out a show I liked is 10 years old now so to not be the oldest thing on this blog I'm talking coelacanths for Wet Beast Wednesday. Coelacanths are rare fish famed for being living fossils. While that term is highly misleading, it is true that coelacanths are among the only remaining lobe-fined fish and were thought to have gone extinct millions of years ago before being rediscovered in modern times.

(image id: a wild coelacanth. It is a large, mostly grey fish with splotches of yellowish scales. Its fins are attached to fleshy lobes. It is seen from the side, facing the top right corner of the picture)

Coelacanth fossils had been known since the 1800s and they were believed to have gone extinct in the late Cretaceous period. That was until December 1938, when a museum curator named Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer was informed of an unusual specimen that had been pulled in by local fishermen. After being unable to identify the fish, she contacted a friend, ichthyologist J. L. B. Smith, who told her to preserve the specimen until he could examine it. Upon examining it early next year, he realized it was indeed a coelacanth, confirming that they had survived, undetected, for 66 million years. Note that fishermen living in coelacanth territory were already aware of the fish before they were formally described by science. Coelacanths are among the most famous examples of a lazarus taxon. This term, in the context of ecology and conservation, means a species or population that is believed to have gone extinct but is later discovered to still be alive. While coelacanths are among the oldest living lazarus taxa, they aren't the oldest. They are beaten out by a genus of fly (100 million years old) and a type of mollusk (over 300 million years old).

(image: a coelacanth fossil. It is a dark brown imprint of a coelacanth on white rock. Its skeleton is visible in the imprint)

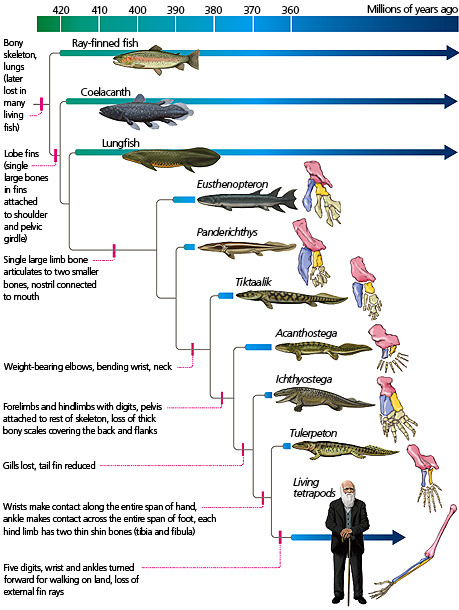

Coelacanths are one of only two surviving groups of lobe-finned fish along with the lungfishes. Lobe-finned fish are bony fish notable for their fins being attached to muscular lobes. By contrast, ray-finned fish (AKA pretty much every fish you've ever heard of that isn't a shark) have their fins attached directly to the body. That may not sound like a big difference, but it actually is. The lobes of lobe-finned fish eventually evolved into the first vertebrate limbs. That makes lobe-finned fish the ancestors of all reptiles, amphibians, and mammals, including you. In fact, you are more closely related to a coelacanth than a coelacanth is to a tuna. Coelacanths were thought to be the closest living link to tetrapods, but genetic testing has shown that lungfish are actually closer to the ancestor of tetrapods.

(image id: a scientific diagram depicting the taxonomic relationships of early lobe-finned fish showing their evolution to proto-tetrapods like Tiktaalik and Ichthyostega, to true tetrapods. Source)

There are two known living coelacanth species: the west Indian ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and the Indonesian coelacanth (L. menadoensis). Both are very large fish, capable of exceeding 2 m (6.6 ft) in length and 90 kg (200 lbs). Their wikipedia page describes them as "plump", which seems a little judgmental to me. Their tails are unique, consisting of two lobes above and below the end of the tail, which has its own fin. Their scales are very hard and thick, acting like armor. The mouth is small, but a hinge in its skull, not found in any other animal, allows the mouth to open extremely wide for its size. In addition, they lack a maxilla (upper jawbone), instead using specialized tissue in its place. They lack backbones, instead having an oil-filled notochord that serve the same function. The presence of a notochord is the key characteristic of being a chordate, but most vertebrates only have one in embryo, after which it is replaced by a backbone. Instead of a swim bladder, coelacanths have a vestigial lung filled with fatty tissue that serves the same purpose. In addition to the lung, another fatty organ also helps control buoyancy. The fatty organ is large enough that it forced the kidneys to move backwards and fuse into one organ. Coelacanths have tiny brains. Only about 15% of the skull cavity is filled by the brain, the rest is filled with fat.

(image id: a coalacanth. It is similar to the one on the above image, but this one is blue in color and the head is seen more clearly, showing an open mouth and large eye)

One of the reasons it took so long for coelacanths to be rediscovered is their habitat. They prefer to live in deeper waters in the twilight zone, between 150 and 250 meters deep. They are also nocturnal and spend the day either in underwater caves or swimming down into deeper water. They typically stay in deeper water or caves during the day as colder water keeps their metabolism low and conserves energy. While they do not appear to be social animals, coelacanths are tolerant of each other's presence and the caves they stay in may be packed to the brim during the day. Coelacanths are all about conserving energy even when looking for food. They are drift feeders, moving slowly with the currents and eating whatever they come across. Their diet primarily consists of fish and squid. Not much is known about how they catch their prey, but they are capable of rapid bursts of speed that may be used to catch prey and is definitely used to escape predators. They are believed to be capable of electroreception, which is likely used to locate prey and avoid obstacles. Coelacanths swim differently than other fish. They use their lobe fins like limbs to stabilize their movements as they drift. This means that while coelacanths are slow, they are very maneuverable. Some have even been seen swimming upside-down or with their heads pointed down.

(image: an underwater cave wilt multiple coelacanths residing in it. 5 are clearly visible, with the fins of others showing from offscreen)

Coelacanths are a vary race example of bony fish that give live birth. They are ovoviviparous, meaning the egg is retained and hatches inside the mother. Gestation can take between 2 and 5 years (estimates differ) and multiple offspring are born at a time. It is possible that females may only mate with a single male at a time, though this is not confirmed. Coelacanths can live over 100 years and do not reach full maturity until age 55. This very slow reproduction and maturation rate likely contributes to the rarity of the fish.

(image: a juvenile coelacanth. Its body shape is the same as those of adults, but with proportionately larger fins. There are green laser beams shining on it. These are used by submersibles to calculate the size of animals and objects)

Coelacanths are often described as living fossils. This term refers to species that are still similar to their ancient ancestors. The term is losing favor amongst biologists due to how misleading it can be. The term os often understood to mean that modern species are exactly the same as ancient ones. This is not the case. Living coelacanth are now known to be different than those who existed during the Cretaceous, let alone the older fossil species. Living fossils often live in very stable environments that result in low selective pressure, but they are still evolving, just slower.

(image: a coelacanth swimming next to a SCUBA diver)

Because of the rarity of coelacanths, it's hard to figure out what conservation needs they have. The IUCN currently classifies the west Indian ocean coelacanth as critically endangered (with an estimated population of less than 500) and the Indonesian coelacanth as vulnerable. Their main threat is bycatch, when they are caught in nets intended for other species. They aren't fished commercially as their meat is very unappetizing, but getting caught in nets is still very dangerous and their slow reproduction and maturation means that it is long and difficult to replace population losses. There is an international organization, the Coelacanth Conservation Council, dedicated to coelacanth conservation and preservation.

(image: a coelacanth facing the camera. The shape of its mouth makes it look as though it is smiling)

#wet beast wednesday#coelacanth#marine biology#biology#zoology#ecology#animal facts#fish#fishblr#old man fish#lobe-finned fish#sarcopterygii

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The oldest vertebrate to ever live was a greenland shark that lived for at least 272 years (in comparison, the previous record holder was a bowhead whale that lived for 211 years).

#fish facts#marine animals#marine biology#shark#shark facts#sharks#fish#sharkblr#fun facts#greenland shark

552 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pando - The Largest Single Organism by Mass and 14,000 years old, and some perspective on just how old that is.

A random thought came to my head last night...

This is Pando.

All of this? Is a single male aspen tree. This entire thing is a single tree with multiple stems sharing a single root system.

It is the largest tree by mass, and the heaviest single organism, weighing in at 6000 metric tons. For perspective, that's 20 blue whales in mass.

But what also intrigues me is that... well. It's an old tree.

Established in 12,000 BCE, meaning it would be 14000 years old by 2023.

By the the last Smilodons died out in 10,000 BCE, it would have already been 2000 years old.

And Pando is still a youngster compared to the high estimate age of this clonal colony of sea grass estimated to be 100,000 years old.

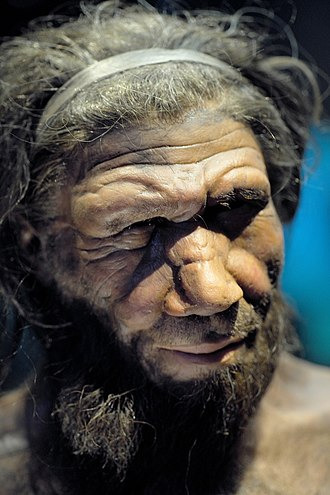

For perspective, when the last Neanderthal died in 40,000 BCE?

This sea grass would have already been 60,000 years old.

If human civilization (as in, the kind of organized polity that can be identified with things as "states" and "urbanization" among a plethora of other things) was established during 5000 BCE, and thus 7000 years old:

Pando would have already been 5000 years old.

The Sea grass colony would have already been 93,000 years old.

And considering that the oldest vertebrate, that is the Greenland Shark can live for 500 years?

All of human civilization encompasses the lifespans of just 14 Greenland Sharks.

I dunno... it just really shows that we pretty are a tiny blip in the grand scheme of Earth's geological history.

A very humbling thought if you ask me.

#paleontology#anthropology#history#ancient history#botany#science#human history#life on earth#pando#greenland sharks#shower thoughts

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

SCLEREVIL (Water/Ghost) & RELICANTIQUE (Rock/Ghost)

RELICANTIQUE (Relic/Antique) is RELICANT's evolution, it evolves when it comes in contact with SCLEREVIL (Sclera/Evil Eye)

RELICANTIQUE is based on the Greenland shark, one of the oldest vertebrates in the world, if not the oldest, and one that can live over 500 years old. SCLEREVIL is based on the Ommatokoita elongata, a type of parasite that can be found attached to the eyes of the greenland shark, where it feeds on its corneas.

#pokemon#fakemon#fake pokemon#fake evolution#greenland shark#relicanth#parasite#ghost type#ghost pokemon#ghost fakemon#rock type#rock pokemon#rock fakemon#water type#water pokemon#water fakemon

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for you blog! I love it so much - I come here daily to read your latest posts.

I'd love to own a snake but alas, I currently live in New Zealand so no snakes for me.

Do you have cool facts about tuatara? I do but I'd love readers of your blog to learn about these cool little reptiles!

It's a huge dream of mine to work with tuatara one day! I've always loved the reptile life of Oceania and literally the only reason I haven't already moved to Australia or even Aotearoa/NZ is because of the limitations on keeping non-native species.

Anyway, aren't tuatara just the coolest? For those unfamiliar, tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) might look like lizards, but they're not! Tuatara are the only surviving members of Rhynchocephalia, the sister order to Squamata, the scaled reptiles (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians).

Rhynchocephalians used to be very widespread, but today they exist only in limited populations in Aotearoa. They were almost driven to extinction by habitat loss and pressure from invasive species, and for a long time the only wild populations were on offshore islands. In a huge success for tuatara conservation, though, populations were reintroduced onto the North Island and there are now hatchlings being born on the North Island for the first time in centuries. There's still so much work to be done to help these amazing reptiles, but it's worth celebrating! The Chester Zoo in England has also welcomed tuatara hatchlings, meaning tuatara have been successfully bred outside of Aotearoa for the first time and indicating possible future success for wider zoo breeding programs across the world!

Tuatara have many anatomical features that are unique among reptiles, and they tell us a lot about the extinct rhynchocephalians. Their teeth arrangement is unique among reptiles, and their lower jaws can slide to cut through bone. They're the only known amniotes who have hourglass-shaped vertebrae, and they have gastralia (belly ribs). Even if they might look kinda like lizards on the outside, their skeleton is wildly different!

Tuatara have the most well-developed parietal eyes of any vertebrates. These are "third eyes" that sit on top of the head, and in most reptiles who have them they're extremely primitive, but in tuatara they have well-developed retinas and a cornea-like structure! Parietal eyes are covered by a thin layer of skin and probably help with thermoregulation and day/night cycle regulation.

They are carnivores and eat a wide diet of insects, lizards, and birds. Juvenile tuatara will hunt during the day so they can avoid being eaten themselves by adult tuatara, who hunt at night.

The name "tuatara" comes from te reo Māori, and means "peaks on the back," a reference to the spines along a tuatara's back. Tuatara are sexually dimorphic, and the spines are larger and more rigid in males. They're used in breeding and defensive displays!

One of the challenges for tuatara conservation is how long it takes them to reach sexual maturity - about 10-20 years, and they tend to have very small egg clutches. They've been recorded to lay up to 19 eggs, but a more typical clutch is as small as 3-6 eggs or even a single egg. These eggs also take over a year to be laid and hatch. They have the slowest growth rates of any reptile, reaching full size at around 30 years and having an average lifespan of around 60 but lifespans closer to 100 not being uncommon.

The oldest known tuatara is named Henry, and he lives at the Invercargill museum on the South Island. He's at least 120 but may be as old as 150, and is still fathering healthy clutches!

Tuatara are simply incredible. They're so unique among living reptiles, and they have so much to tell us about a mostly-extinct order of reptiles. Plus, like, you can't deny they're so cool and adorable!

#not a rating#tuatara#tuatara anatomy#sorry for the long post. being asked to talk about tuatara awakens something within me#long post

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists discover 512 yr. old shark, which would be oldest living vertebrate on earth. Greenland sharks tend to outlive other creatures b/c they're a very slow-growing species and don't reach maturity until 150 yrs. old.

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Salii’Qi - Saliinthia’s Sophonts

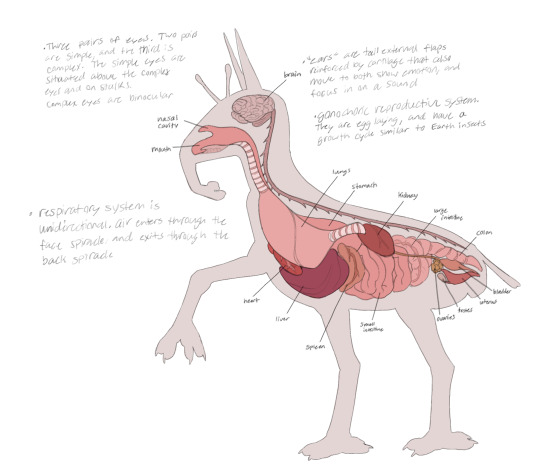

The primary sophont species residing on the warm, Earth-like world of Saliinthia are the Salii’Qi, a race of strange mammalian-insect creatures. They have dispersed into four main subspecies, two sedentary groups who live in the forests and islands respectively, and the two nomadic groups who call the grasslands and deserts home. Through this blog I will delve deep into their various cultures, religions, technology, and day to day lives living on Saliinthia!

Basic Biology

The Salii’Qi evolved from intelligent, largely carnivorous pack hunters, with the grassland subspecies being the oldest ones. They have intelligence equivalent to that of human beings, though tending to be better at problem solving. Their mammal-like biology gives them warm blood and dense bones, though their skeleton is derived from a graphite filled exoskeleton similar to that of insects, that was slowly internalized over the course of millions of years. They are egg layers, and have a complex life cycle not unlike that of an Earth caterpillar or beetle.

Salii’Qi have three sets of eyes, two are simple and detect movement and light only, while the third pair is complex and has an expanding and contracting pupil like Earth’s vertebrates. They hear through bright colored ear flaps held up by cartilage, able to swivel and pin to show emotion or focus in on certain sounds.

Salli’Qi have four pairs of limbs, two are used for walking while the other two are used for physical manipulation. One pair of limbs are attached to the skull. These “arms” evolved from pedipalps, now used for eating and handling weapons or other objects. The pedipalps are weaker than their forearms, so they usually use those for heavier work like lifting large objects. With the evolution of centaurism in these creatures, they lost a lot of flexibility in their backs, and so can no longer keep their forearms on the ground for long periods of time.

The skeleton of the Salii’Qi have a dark color due to the high amount of graphite present in their bones, with black teeth stronger than ours. Their bones are dense and very similar to ours, although the ribs are free floating and connected with cartilage. Some of the vertebrae located near the end of the body are fused, which aid in supporting the back. Ancient relatives had a connected skeleton below the skin, which resembled that of insects. To allow for more flexibility and dexterity, those bones have now been reduced to cover less area.

Salii’Qi have organs very similar to ours, but have a unidirectional respiratory system. They breathe in through two spiracles beneath their eyes, and after passing through the lungs, it is exhaled through the two spiracles placed behind the first pair of leg’s shoulders. This allows faster replacement of oxygen in the bloodstream, fueling their insect-like biology.

Their digestive system extremely similar to ours, the only notable difference being the tiered stomach, which allows for tough protein rich plant matter to be digested.

Salii’Qi have a gonochoric reproductive system, meaning they have two sexes. Both sexes have bright colored ear flaps and antennae, but during the spring the male coloration deepens for mating. Females are slightly larger than males, and have duller colors. Depending on the culture, females may take multiple male partners during the mating season, or only keep one partner for their whole life.

Subspecies

The Salii’Qi are spread over four main subspecies, and are regional variants. As mentioned before, the nomadic grasslanders were the first successful variants, which then radiated into the forest, desert, and island subspecies. As the names imply, they live in settlements and groups around specific biomes they are best adapted to.

The foresters are mostly a sedentary group, and also physically the largest. They eat the most fruit and plant matter out of any other , and have learned how to farm and selectively breed crops. They have long, thin limbs for reaching up into the vegetation, and upturned simple eyes to see differences in the shadows above. They are skittish and try too keep to themselves, but enjoy trading their crops with other groups.

Grasslanders are nomadic, but have specific areas they return to during nesting season. They follow the herds of large grazers who roam the grasslands, using their good stamina to their advantage. They are a proud and strong group, seen as kind and humorous. They are artisans, creating unique goods and clothing out of hides and pelts for trading with other groups.

Desert dwellers live in smaller groups, and instead of hunting, they primarily ranch and travel with herds of domesticated livestock. Desert Salii'Qi forage desert fruits, roots, and other plant matter before a harvest. They travel to feeding grounds during the fall and winter, but return to fertile river communities during the spring and summer where plants for livestock flourish along the banks. During this time, the desert Salii-Qi raise their children to take on their next journey.

Islanders are small, social Salii'Qi who settled on an archipelago millions of years ago. They are the most well adapted group and the second oldest subspecies. Islanders have partially webbed feet, seal-like fur, powerful limbs, and higher back spiracles which makes it easier to spend time in the water. They primarily feed on fish and island fruit which they've selectively bred. Islanders mainly spearfish, but also use boats for fishing and trade. They routinely voyage to the mainland to trade goods, and some have even settled on the mainland shores.

#salii'qi#saliinthia#spec bio#speculative biology#biology#xenobiology#alien#speculative fiction#speculative ecology#aliens#sci fi#evolution

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spectember D14: The Future

Has been 200 million years since life on earth changed, a destructive astronomical event wiped out most of the surface life, leaving only the deep-water fauna almost untouched, and they have tried to recolonize the surface little by little, many squids, arthropods, bony fishes and also a very ancient group of vertebrates that passed this cataclysm, sharks.

Sharks have had a constant story of survival over the last 200 million years since they evolved, passing the KPg with ease, and counting back their oldest relatives that had similar body forms, that gives another 200 million years. Although people often want to remark they are sort of “living fossils” that’s just relative superficial as many groups that came before always had peculiar and unique anatomies for being of different groups, and now with the extinction of the surface-dwelling species like lamniform, there would be another wave of new differently forms, preserving some features of their predecessors but changed for the anatomical differences of other groups.

These are the Damselsharks, descendant of lantern sharks (Squaliformes, Etmopteridae) that took over the surface and diversified, sort of adopted a shape similar to the extinct Lamniformes and so had to adjust some of their anatomy to make it fit to the pelagic predatory role in the ocean, with a drop shaped body and a tall head, very big eyes result of their still prevailing deep water behavior, as well prominent pectoral fins that resemble the ones of a mako shark, short dorsal, pelvic and anal fins and a well developed C shaped heterocercal tail. Their jaws remain similar to their ancestors in articulation and position, but adjusted to tear and cut meat with new types of dentitions depending of their prey.

Many species have lost their bioluminescence but others preserved it, even further developing certain communication behavior that can help them to coordinate whole groups while hunting, which one of the most impressive examples as well the largest species of this family, the Shakopath, a 4 meter long species with characteristic bioluminescent arrangement around the belly and different sized long spots around the pelvic region, they swim in large groups of 20 individuals, patrolling the surface for any potential prey, either large squids that camouflage with their environment and often compete for food or can hunt one of these sharks in an ambush; although also they can preffer fishes that swim or fly over the water, many of the pelagic species crustaceans and even other species of sharks which are also long distant relatives of the Damnselsharks.

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

greenland sharks;

squaliformes

sharks in the squaliform family are found in nearly every marine habitat, they have long snouts and a short mouth, five gill slits, two fins, and no anal fin.

greenland sharks are the longest-living vertebrate known to humans

it is estimated that they live an average of 250-400 years

they’re primarily found in cold water environments in the arctic and north atlantic oceans.

one of the largest cartilaginous fish at up to 7 meters(around 23 feet) and 1,025 kilograms(2,260 lbs), but most are around 2-4 meters long

little is known about how these sharks reproduce

females are thought to reach sexual maturity at around 4 meters(13 feet), and it takes them around 150 to achieve this size

they give birth to around 10 offspring at a time, unlike how whale sharks give birth to around 300 at a time

scientists believe, but aren’t sure, that greenland sharks are independent from birth. this is common within shark species, most of them don’t need parental care

it is thought that the oldest greenland sharks are over 500 years old, that’s older than the united states!

they’re very rarely encountered by humans because they live in such deep and cold water

they live anywhere between the sea’s surface and 2,200 meters(7,200 feet) deep

greenland shark’s meat is toxic unless prepared properly because of the trimethylamine oxide in their tissues that helps protect their enzymes and other things from the cold environment

they eat mostly smaller sharks, eels, crustaceans, sea birds, and many other things.

interestingly, large land mammals have been found in their stomachs. this includes horses and reindeer that likely fell through the ice

there has been one report of a possible greenland shark attack dating back to 1859

@mushroomcarrotstick i will post the dwarf lantern shark facts tomorrow!!

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miosurnia vs Primoptynx

Factfiles:

Miosurnia diurna

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Diurnal Hawk-Owl from the Miocene

Time: 7.25 to 11.1 million years old (Tortonian stage of the Miocene epoch, Neogene period)

Location: Liushu Formation, Gansu Province, China

Miosurnia was a small owl, weighing around 318 grams and having a similar overall size to its living relatives, the modern hawk-owls. And, like its living relatives, Miosurnia was diurnal (based on its eye shape) - a rarity in owls, mainly seen in Hawk-Owls and putative early members of the group. As such, this small clade of diurnal owls has a longer and more extensive range than previously thought. If so, it may have eaten a variety of small diurnal mammals, similar to small kestrels in many habitats today. This allowed it to live alongside a wide variety of other avian predators, including many Old World Vultures and falcons. Like other diurnal owls, Miosurnia lived in a large open habitat, and this was one right after the great grassland explosion of the Miocene. As the polar ice sheets grew, these large open habitats expanded across the planet, greatly affecting many ecologies. In addition to other birds of prey, Miosurnia shared its habitat with Panraogallus, ostriches, sandgrouse, Ergilornithids, and many mammals such as Cahlicotheris, Gomphotheres, horses, giraffids, and buff hyenas.

Primoptynx poliotauros

Artwork by @otussketching, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: First Owl from the Graybullian

Time: 56 million years ago (Thanetian stage of the Paleocene epoch, Paleogene period)

Location: McCullough Peaks, Willwood Formation, Wyoming

Primoptynx is one of many early owl fossils, but it is unique - in that it’s currently the oldest known owl, appearing during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, soon after the end-Cretaceous. This owl was weird in a variety of ways, lacking many of the later adaptations that make owls unique among birds of prey. The weirdest thing, however, isn’t something it’s missing - its the unique morphology of the foot, where the first and second toes are much larger than expected, much like the feet of diurnal birds of prey (rather than those of owls). Primoptynx was also huge, bigger than other early owls known from the region such as Eostrix. While smaller members of the group at the time were eating small vertebrates, Primoptynx seems to have been adapted for eating much larger prey, such as mid sized vertebrates like those preyed on by Harpy Eagles and other larger birds of prey today. This not only shows that owls tried on a lot of ecological “hats” prior to settling into their modern niches, but also that large birds of prey were fixtures in ecosystems very early on in the Cenozoic. Since early fossils of diurnal birds of prey are comparatively rare, this fills in a major ecosystem gap for the Willwood and beyond. Diurnal owls, like Primoptynx, probably then went extinct due to the radiation of modern diurnal birds of prey (hawks, eagles, and falcons). In the Willwood, Primoptynx was surrounded by many other birds as well as mammals - such as weird stem-ducks and stem-chickens, Lithornithids, Gastornis, Sandcoleids, and a variety of early mammals, all of which would probably have made good prey items for Primoptynx.

DMM Round One Masterpost

#dmm#dinosaur march madness#dmm round one#dmm rising stars#palaeoblr#dinosaurs#paleontology#polls#bracket#march madness#miosurnia#primoptynx

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Worlds: Early Humans May Have Shared Ancient Europe With This 1,000-Pound Bird

A new study suggests a half-ton bird roamed Europe nearly 2 million years ago, around when our Homo predecessors were first entering the region.

— By Katherine J. Wu | Wednesday, June 26, 2019 | NOVA

An artist's impression of Pachystruthio dmanisensis, an extinct giant bird that a new study suggests lived in early Europe around the same time that early humans first entered the region around 1.8 or 1.7 million years ago. Image Credit: Andrey Atuchin

Traveling to a foreign place is tough under any circumstances. But you can bet your bonnet it was a particularly onerous task 2 million years ago, around the time when early humans first left the African continent.

On these early sojourns, our predecessors didn’t just lack the luxuries of modern wayfarers. Upon entering what’s now Europe, they also had to contend with unpredictable food and water sources, sharp-toothed carnivores… and, apparently, some insanely big birds.

Or, at least, that’s what a new fossil find suggests. According to a study published today in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, early Europe may once have been home to a now-extinct species of giant, flightless bird that clocked in at close to 1,000 pounds, at least three times the weight of your savanna-variety ostrich, the largest bird still alive today.

If the finding pans out, this behemoth bird could occupy a fortuitous juncture in space and time. Not only would it be among the first of its kind documented above the equator—but it may also have had the distinct honor of sharing the landscape with ancient humans at a pivotal point in their geographical diversification.

“If you had asked me before this paper if a giant bird could compete with herbivorous mammals on their own turf in an ice age world, I probably would have said no,” says Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, a vertebrate paleontologist at Yale University who was not involved in the study. “But this is quite a remarkable bird...this study could really add to our understanding of the ancient landscape in which some of our earliest relatives lived.”

The femurs of Pachystruthio dmanisensis, an extinct giant bird (panels A, C, E, F), and a modern common ostrich (Struthio camelus) (panels B, D). Image Credit: Zelenkov et al., Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 2019

It’s only once in a blue moon that evolution cooks up a bird the size of a grand piano. As far as we humans know, it’s happened just a handful of times throughout history, perhaps most famously in the mihirungs (Dromornis) of Australia and the elephant birds (Mullerornis, Vorombe, and Aepyornis) of Madagascar, each of which may have weighed close to 1,500 pounds.

After all, it’s not easy being big. Bulk certainly has its perks, but the downsides range from conspicuousness (a problem for predators and prey alike) to extra exposure to the elements. On the whole, researchers still don’t have a good grasp on all the conditions that precipitated the rise and fall of gigantism in most animal lineages, which makes every new instance a potential paleontological goldmine.

So far, this new specimen is represented by only a single, 15-inch femur unearthed from the Taurida Cave on what’s now the Crimean Peninsula. Without more of the skeleton available, it’s tough to make more than a handful of approximations. But by analyzing the thigh bone’s shape and size, a team led by study author Nikita Zelenkov, a paleontologist at the Russian Academy of Sciences, assigned to the species Pachystruthio dmanisensis—a lineage distinct from the Struthio genus that includes the common ostrich (Struthio camelus).

The name also contains a nod to the nearby archaeological site of Dmanisi, Georgia, where several ancient animal remains (including, Zelenkov notes, a couple giant bird femurs described in 1990 that look strikingly similar to this new one) and some of the oldest known Homo fossils outside of Africa have been uncovered

Using the bone’s dimensions, the researchers estimated the bird’s body mass to be around half a ton—a quantity nearly on par with an adult polar bear. Through sheer weight alone, P. dmanisensis may be the largest known avian in the northern hemisphere, Zelenkov says.

Based on the fossil’s age—about 1.8 or 1.7 million years old—P. dmanisensis likely kept similarly colossal company. At the time, the creatures that stalked the earth included giant hyenas and supersized versions of today’s carnivorous cats, both of which would have gladly noshed on flightless fowl.

Luckily, it seems this bird had some tricks up its wing. Like many other heavyset avians of the past, P. dmanisensis boasted thick, dense bones that kept it from taking to the skies. But compared to its ancient cousins like elephant birds, this bird had a femur that was relatively slender and long. The bone almost looks like a stockier, more robust version of something you’d find in a modern ostrich—a bird that can sprint at speeds near 45 miles per hour, says Jessie Atterholt, a vertebrate paleontologist and comparative anatomist at the University of California, Berkeley who was not involved in the study.

This similarities hint that P. dmanisensis might have been a pretty capable runner, Zelenkov says.

Of course, with a few hundred extra pounds on its massive frame, P. dmanisensis was almost certainly not dashing about at the same speeds as its distant modern cousin, and probably couldn’t sustain long bouts of continuous movement, says Delphine Angst, a paleobiologist and fossil bird expert at the University of Bristol who was not involved in the study. “It could probably run when it had to,” she says, “but this might not have been [its] favorite way of locomotion.”

One of the Dmanisi skulls, a collection of early human remains uncovered in Dmanisi, Georgia that date back to around 1.8 or 1.7 million years ago. The skulls are thought to represent some of the earliest groups of ancient humans that emigrated from Africa. Image Credit: Desc/Em, flickr

But even if the bird was cornered by a particularly dogged carnivore, Bhullar says, it probably had enough heft to hold its own. Though it lacked the ability to fly, he adds, this bird was clearly able to coexist with some of the most formidable foes of the era—including, perhaps, the most dangerous predators of all: early humans.

At least, for a time. P. dmanisensis eventually went the way of the dodo (though if we’re getting technical, it’s really the other way around). What’s not known, however, is why.

Given P. dmanisensis’ placement in time and space, early humans might seem an obvious culprit. (If so, it wouldn’t be the first time a Homo species has driven a big bird to extinction.) But the story might be more complicated than that. Zelenkov thinks there’s a decent chance the birds disappeared without any help from the genus Homo, instead succumbing to a combination of pressures from a changing climate, predation, and disease.

Without more fossils, it’s unclear if these birds interacted much with humans at all, says Julia Clarke, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Texas Austin who was not involved in the study. Though the archaeological evidence places the two groups in the same geographic region and date range, more data to suggest they occupied the same sites would strengthen the case, she says.

But all that has to start somewhere, Atterholt says. “It’s exciting that these birds made it into this part of Europe,” she adds. “Now that they know where these fossils are, hopefully field work will continue in this area.”

411 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're going to take it slow this Wet Beast Wednesday and talk about Somniosus microcephalus, the Greenland shark. Its one of the sleeper sharks, a family named for their very slow movement and generally low-activity lifestyles. Greenland sharks follow the rule that slow and steady wins the race. With a top speed of 2.6 km/h (1.6 mph), the Greenland shark has the slowest speed of its size of all fish. They also have a slow metabolism which correlates with a very long lifespan. The lifespan of these sharks isn't known for sure, but given that they grow at a rate of about 1 cm per year and can reach around 6 meters in length, they can live a pretty long time. Normal methods of aging sharks don't work on the GS. Sharks are usually aged by counting growth rings on fin rays or vertebrae, but Greenland sharks don't have fin spines and their vertebrae are too sift to form growth rings. In 2016, a paper titled "Eye Lens Radiocarbon Reveals Centuries of Longevity in the Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus)" by Nielsen et al. was published that described a new aging method in which crystals in the eye lens could be radiocarbon dated to provide and age estimate. The oldest shark they tested was aged at 392 ± 120 years old. If the lifespan falls on the upper end of that range, it could give the GS a maximum age of 500 to 600 years old. The same paper also estimated that they don't reach sexual maturity until around 150 years old. The GS is officially listed as the longest-lived of all vertebrates.

It looks like somebody tried to draw a shark from memory (image: a Greenland shark swimming under ice)

The extreme age and slow lifestyle of the sharks is linked to their habitat. Despite the name, they are not only found around Greenland. In fact, they live in very cold waters (0.6 - 12 degrees C or 31 - 54 degrees F) in the north Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. They are the only shark species to live in arctic waters all year round. It is likely that they have a much larger habitat range than we know as they spend most of their time in very deep water. One specimen was found as far south as the Caribbean. It's possible that the north Atlantic and Arctic Oceans are the only places in their range that are cold enough for them to tolerate surface conditions and in the rest of their range they stay in deep, cold water. Being an ectothermic (cold-blooded) animal living in very cold conditions requires a very slow metabolism and slow metabolisms are linked to longer lifespans. A slow metabolism also requires less energy, which is very advantageous for seep-sea animals, who may be forced to go for months or longer between meals. The size of the shark may also be linked to its habitat. At up to 7 meters (23 feet) long and 1,400 kg (3090 lbs), the GS is one of the largest fish in the world. This size could be an example of deep-sea gigantism, a phenomenon in which deep-sea animals grow much larger than their shallow-water relatives. There are many proposed explanations for deep sea gigantism, including cold temperatures inducing growth (Bergmann's rule), improved foraging ability, defense against predators, and greater dissolved oxygen availability in colder and deeper waters. Because of their abyssal habitats, Greenland sharks are rarely observed in the wild and we know little about their natural behavior.

(Image: a scuba diver swimming next to a Greenland shark)

What does a large carnivore living in food-scarce deep water eat? Just about everything. Greenland sharks are generalists who will eat almost any meat. They are both scavengers and active predators, with a diet consisting primarily of squid as juveniles and fish as adults. Most of what we know about their diet comes from the stomach contents of dead specimens as they have very rarely been observed feeding in the wild. Seals also make up a large portion of their diet. As it's very unlikely that such a slow shark could chase down and catch a seal for lunch, the shark likely targets sleeping seals. Greenland sharks are scavengers who likely get a lot of nutrition from carrion. They have very sensitive noses that they use to track down rotting meat. Stomach contents have revealed meat from various animals, including polar bears, moose, and reindeer. They are known to follow fishing boats to snatch up any scraps. Greenland sharks are apex predators who play an important role in the Arctic ecosystem.

(Image: a Greenland shark captured by a fishing boat)

As mentioned above, Greenland sharks are estimated to reach sexual maturity at around 150 years old. They are ovoviviparous, meaning that the eggs hatch while still in the mother, who then gives live birth. A typical litter has around 10 pups (likely the maximum given the metabolic requirements of reproduction) that are about 38-42 cm (15-16.5 in) long. Due to their lifespan, it is estimated that a single female could produce between 200 and 700 pups during her life. Unconfirmed reports have been made of them hybridizing with other sleeper sharks.

(Image: a 100-year old juvenile shark that washed up on a beach in England)

Greenland sharks are often found infested by the parasitic copepod Ommatokoita elongata. This parasite attaches itself to the cornea of the eye and infests both the Greenland shark and the Pacific sleeper shark and dangles out of the eye like a thread. The presence of the copepod damages the eye, leaving the shark almost if not entirely blind. This doesn't actually seem to hurt the shark that much as they rely mostly on smell and hearing. One hypothesis stated that the copepod may bioluminesce to attract prey to the shark, but this remains unconfirmed.

(Image: a close-up of a Greenland shark eye infested with a copepod)

Now to address the elephant seal in the room: Greenland sharks stink. All elasmobranchs have concentrations of the compounds urea and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) in their bodies, but the GS has a higher concentration of these compounds than other species. The compounds are waste products retained by elasmobranchs to aid in buoyancy and the GS has more because they also help resist the pressure of the deep ocean. The concentration of urea is high enough that you can smell it if the shark is near you. Urea is a key component of urine. Greenland sharks smell like piss. The high levels of TMAO makes Greenland shark meat toxic to humans. Despite this, people still eat the meat, but it must be treated first. This can be done by boiling the meat multiple times or by fermenting it. A national dish of Iceland, kæstur hákarl, consists of Greenland shark meat that has been buried underground in gravelly sand and pressed with stones, then left to ferment for 6-12 weeks. It is then dug up and cut into strips, which are hung up and left to dry for several months. Apparently first time eaters are known to gag because of how much ammonia is in the meat. I don't think I'll try any.

(Image: hákarl hung up to dry)

Because of their deep-sea habitat, Greenland sharks have relatively few interactions with humans. In the past, They were hunted for their liver oil, but in modern days, there is no fishery for them. Greenland sharks are classified as vulnerable by the IUCN. Their primary threat is bycatch and they are likely being affected by ocean warming and loss of sea ice in the Arctic. Because of their slow maturity and low fecundity, Greenland sharks are particularly vulnerable to population loss. There are no recorded attacks on humans. The species features in the legends of the Inuit. The legendary first Greenland shark was named Skalugsuak and one story says it was born after a woman washed her hair with urine (a lice remedy) and dried it with a cloth. The cloth then blew into the ocean and turned into Skalugsuak, who still smells like urine. Another legend says that the shark lives in the urine pot of Sedna, the sea goddess, explaining its smell.

(image: scientists tagging and releasing a small Greenland shark)

#wet beast wednesday#fish#fishblr#shark#greenland shark#marine biology#marine life#ecology#zoology#ichthyology#long post#animal facts#old man that smells like pee

322 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lungfish sculpture, Bundaberg

The Australian Lungfish (Neoceratodus forsteri) is the oldest known living vertebrate species. It has a long heavily scaled body, a wide flat head and lobed, paddle-shaped fins. It is the most primitive member of the six lungfish species that survive today, and the only species in the family Ceratodontidae.

Lungfishes belong to an ancient lineage of air-breathing fishes that first appeared in the fossil record about 380 million years ago and were common during the Devonian Period.

19 notes

·

View notes

Note

not COB related quetion, but instead shark related fact.

The Greenland Shark is the world's oldest living vertebrate, with a lifespan of up to 500 years.

This Shark also has a diet that may include polar bears and reindeer.

I'm actually pretty aware of all of these, however I still always appreciate a good shark fact and the fact that everyone associates them with me. 👍

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

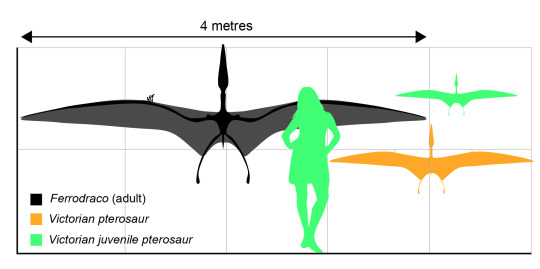

Now, scientists have confirmed that 107-million-year-old fossils found in Victoria are the oldest remains of pterosaurs that soared across the Australian landscape.

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles, that lived alongside their dinosaur cousins during the Mesozoic Era, which began 252 million years ago.

They were the first and largest vertebrates to fly — taking to the skies 65 million years before birds – and they lifted off using membranous wings that were more bat-like than bird-like.

Pterosaur fossils are very rare, especially in Australia.

That's why palaeontologists were excited when two tiny fossils were found embedded in a seaside cliff near Cape Otway, 220 kilometres south-west of Melbourne in the 1980s...

28 notes

·

View notes