#new atheism

Text

"Atheism, true ‘existential’ atheism, burning with hatred of a seemingly unjust or unmerciful God, is a spiritual state; it is a real attempt to grapple with the true God whose ways are so inexplicable even to the most believing of men, and it has more than once been known to end in a blinding vision of Him Whom the real atheist truly seeks. It is Christ who works in these souls. The Antichrist is not to be found in the great deniers, but in the small affirmers, whose Christ is only on the lips. Nietzsche, in calling himself antichrist, proved thereby his intense hunger for Christ…"

~Fr. Seraphim Rose

23 notes

·

View notes

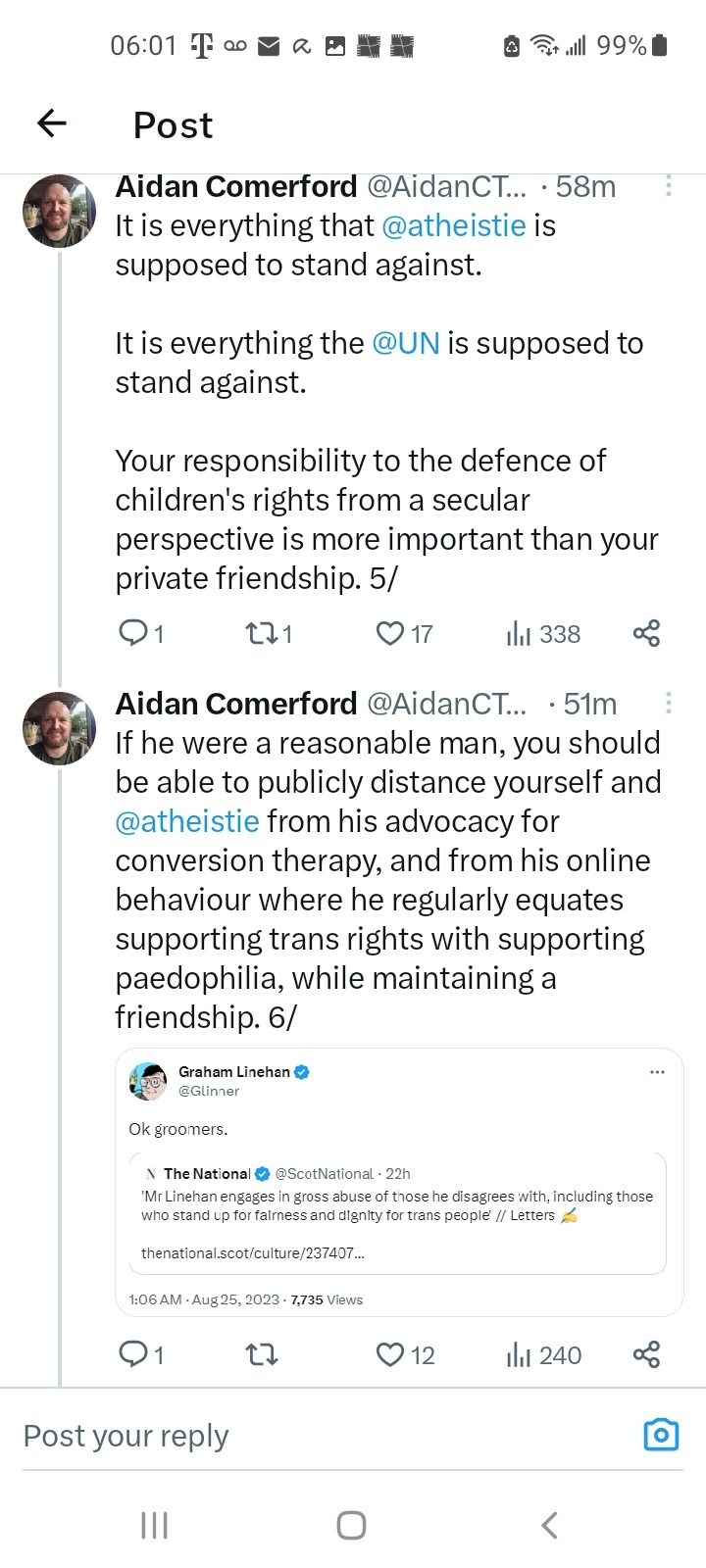

Text

Thanks anarchospirituality, for condensing my 2012 new atheist thoughts about God and my 2024 dionysian-panentheistic thoughts about God into an easy-to-digest doge meme with silly little guys in it

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Along with serving as ideological cover for the War on Terror, what made New Atheism pathetic was that it used shallow criticism of the few straggling remnants of organised religion in order to distract from and legitimise post-industrial society's new priesthood of advertising executives, Silicon Valley tech barons, and neoliberal thinktank cretins. Theirs is the real cultural despotism of our times, and a modern Jean Meslier or Spinoza would identify them as the clerics to be hanged.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Matt Johnson

Published: Jul 24, 2023

Remember “New Atheism”? In the mid-to-late aughts, public debates over religion suddenly expanded in scope and intensity. University auditoria, theaters, and even churches drew capacity crowds for public discussions about the existence of god and whether or not religion is a positive force in the world. Humanist and secular groups proliferated, particularly on campus and online, and a series of blockbuster books by authors like Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Christopher Hitchens sold millions of copies worldwide, catapulting atheism into the mainstream. In their turn, these books inspired a constellation of other writers and intellectuals who believed that an explicit attack on religion was long overdue.

One of those writers was Konstantin Kisin. In a recent Substack article, Kisin explains that he was drawn to the New Atheists for their ability to “re-articulate the importance of Enlightenment values of truth, science and liberty from religious dogma.” He describes them as “daring, counter-cultural figures who could use their erudition, wit and refreshing honesty to effortlessly take apart the tired old arguments for a religious worldview” He says they were “smart, charismatic and, above all, they were cool.” He adds:

The new atheists were exciting because they were saying something new, challenging the dogma of their day and speaking truth to power. Not content with proving that religion wasn’t true, they ventured further in attempting to prove religion was, at best, unnecessary and, more likely, harmful. To this end, Dawkins wrote The God Delusion in 2006, with Hitchens delivering God is Not Great the following year. The argument was no longer about encouraging religious people to calm down and leave the rest of us alone, it was increasingly that religion was inherently wrong and bad. It was around this point that I began to lose my faith in atheism.

So, after praising the New Atheists for the courage and honesty with which they confronted religion, Kisin declares that this combative approach was, in fact, the source of his disillusion. It’s a strangely uneven passage. Kisin acknowledges that the appeal of the New Atheists—what made them “daring, counter-cultural figures”—was their willingness to deconstruct “tired old arguments for a religious worldview” and fight for “liberty from religious dogma.” He’s probably right about this—it was difficult to be a fan of the New Atheists without seeing some value in their claim that religion is “inherently wrong and bad.” They aggressively violated social taboos that protected religion from forceful criticism. They described religion as a powerful engine of irrationality, a source of tribalism, hatred, and conflict, and a generally noxious force that (in Hitchens’s words) should be relegated to the “bawling and fearful infancy of our species.”

If Kisin didn’t like this sort of rhetoric, it’s difficult to see what he admired about New Atheism in the first place. As he explains his reasons for rejecting New Atheism—he now describes himself as a “lapsed atheist”—his rationale becomes even more opaque:

First, it was clear to me that to attempt to challenge Islamic extremism with facts and logic as Dawkins, Hitchens and Harris had done was to fail on purpose. Despite their efforts, most of the Western world today operates under de facto blasphemy laws which are enforced not by religious activists lobbying for censorship but by knife-wielding fanatics and suicide bombers.

It’s bizarre to criticize the New Atheists—and Harris and Hitchens in particular—for the existence of “de facto blasphemy laws” in the West, as it would be difficult to find two figures who were more vociferously opposed to self-censorship and liberal capitulation in the face of Islamic extremism in the 21st Century. And surely the New Atheists’ use of “facts and logic” to resist theocratic encroachments on civil society shouldn’t be a point against them. Given Kisin’s position on the threat of Islamic fundamentalism, shouldn’t he be a little more tolerant of the New Atheists’ unsparing criticism of religious violence and extremism? Instead, he writes:

The liberalism that the new atheists so enthusiastically espoused, the idea that we should be free to criticise, mock and satirise anything, including religion, only works when the Government is willing to protect you from the consequences. In seeking to liberate us from the tyrannical instincts of dogmatic Christians, the new atheists delivered us into the hands of a different and far more pernicious religious zealotry from which the ordinary citizen has no security at all.

Of course free expression in liberal societies is ultimately dependent upon legal and physical protections from the state. When homicidal theocrats bearing automatic weapons show up at the offices of Charlie Hebdo or an acolyte of Ayatollah Khomeini jumps onstage and repeatedly plunges a knife into Salman Rushdie, the confrontation with religious violence is no longer a matter of ideas, it’s a matter of law enforcement. Kisin’s argumnt recalls the line taken by British reactionaries who complained about the taxpayer-funded protection that Rushdie received after Khomeini first issued his fatwa in 1989—a cringing complaint Kisin understands well, as he has criticized it before. Kisin’s second sentence implies that the New Atheists’ attacks on Christianity somehow increased the threat posed by Islamic radicalism, but as noted, New Atheists like Hitchens and Harris were every bit as critical of Islam, if not more so.

The title of Kisin’s article is “The Atheism Delusion.” He now regards religion as “useful and inevitable.” The argument that religion is inevitable is one the New Atheists have always taken seriously: Hitchens described religion as “ineradicable”; Dennett’s book Breaking the Spell examined the ways in which religion evolves and survives over time; a central part of Harris’s career is channeling the religious impulse into secular forms of introspection and mindfulness; and Dawkins acknowledges that religion may reflect a deep psychological need among many people. Where the New Atheists part company with Kisin is over his argument that religion is useful—particularly in the third decade of the 21st Century.

The religious impulse may be ineradicable, but that doesn’t mean the level of overall religious commitment in society is stable. When Harris published The End of Faith in 2004 (the first of the major New Atheist books), membership in religious institutions among American adults was around two-thirds—a proportion that had collapsed to 47 percent by 2020. This means that the percentage of American adults who said they belonged to a church, synagogue, or mosque fell below a majority “for the first time in Gallup’s eight-decade trend” a few years ago.

Recent Pew surveys reflect this trend: since 2007, the proportion of Americans who identify with Christianity has fallen from 78 percent to 63 percent, while those who describe themselves as atheists, agnostics, or “nothing in particular” surged from 16 percent to 29 percent. The share of Americans who say they “seldom or never” pray has jumped from 18 percent to 32 percent, along with a corresponding decrease (58 percent to 45 percent) in the number who pray daily. While 16 percent of Americans said religion was not at all or not too important in their lives in 2007, one-third now say so. Meanwhile, the proportion who describe religion as “very important” is down from 56 percent to 41 percent over the same period.

There has been a similar phenomenon of secularization in Western Europe. Although the majority of Western Europeans identify as Christians, the prevalence of this identification varies greatly—from 80 percent in Italy to 41 percent in the Netherlands. Across the region, there have been significant declines in the populations who say they remain Christian after being raised Christian: 83 percent to 55 percent in Belgium, 79 percent to 51 percent in Norway, 92 percent to 66 percent in Spain, and large decreases in a dozen other countries. At the same time, the proportion of Western Europeans who are now religiously unaffiliated shot up: just 15 percent of Norweigians say they were raised unaffiliated, but the proportion who are unaffiliated now has risen to 43 percent. In the Netherlands, the increase was 22 percent to 48 percent; in Belgium, 12 percent to 38 percent; in Spain, five percent to 30 percent.

As traditional religion declines in the West, it has become increasingly fashionable to argue that new secular religions are taking its place: hyper-tribal and increasingly intolerant political factions; conspiracy cults like QAnon; the “transhumanism” movement (which looks forward to a day when technology will help us live forever); environmental movements that warn of apocalyptic consequences if their counsel isn’t heeded; and social justice activists who decry the original sins of racism and other forms of bigotry.

According to Kisin, the “absence of old religion seems to produce only a vacuum into which a new religion rushes in.” Kisin believes “old religion” is a bulwark against what he describes as the “woke warriors who think every problem in society is caused by an ‘ism.’” He argues that wokeness is a “new religion [that] has just as little regard for the truth as the old ones. That’s why Richard Dawkins who spent his best years arguing with creationists is now increasingly forced to explain basic biological concepts like the inability to change your sex by incantation on national television.”

Yet again, Kisin has picked a strange fight with the New Atheists. As he notes, Dawkins is decidedly anti-woke—he’s often critical of the language used by trans activists (which downplays the biological reality of sex differences), he argues that there’s no such thing as “Western” science (which is often presented as somehow racist or neo-colonial), and so on. Meanwhile, Harris is concerned about what he regards as the “woke capture” of major institutions, and Hitchens warned readers of his 2001 book Letters to a Young Contrarian that they should “have nothing to do with identity politics.”

By undermining traditional religion, Kisin believes the New Atheists opened the door to the emergence of new progressive dogmas. This idea is increasingly pervasive: “The rise of this new religion,” writes Toby Young in a recent essay for the Catholic Herald, “has coincided with the decline of Christian worship in the English-speaking world … which suggests it’s filling a ‘God-shaped hole.’” In his 2019 book The Madness of Crowds: Gender, Race and Identity, Douglas Murray argues that the collapse of “grand narratives” once provided by religion has driven efforts to “embed a new metaphysics into our societies: a new religion, if you will.” Books like John McWhorter’s Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America, Andrew Doyle’s The New Puritans: How the Religion of Social Justice Captured the Western World, and Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos make similar claims.

It’s true that contemporary progressivism has acquired certain religious characteristics: zealous adherents, rituals of excommunication, a concept of original sin (in the form of racism or other types of bigotry), and ways to atone for that sin (such as taking the knee). But the same could be said of many social and political movements throughout history. Godless communism, for example, has often been described by former adherents as a religious phenomenon—a 1949 collection of anti-communist essays by André Gide, Richard Wright, Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender, Arthur Koestler, and Louis Fischer was titled The God That Failed. It isn’t easy to adjudicate what constitutes a secular religion.

The notion that we abandoned our old faiths and replaced them with the new alternatives is too tidy and simplistic. For one thing, the process of secularization has been gaining momentum for decades, long before the “Great Awokening.” For another, unlike the Pew researchers who ask respondents how their religious views have evolved over time, the critics of progressive dogma don’t provide much evidence for their claims about the ways in which religion is supposed to have been supplanted by this new faith. Isn’t it possible that many religious people identify with elements of progressivism? Black Americans are disproportionately religious and far more likely than their fellow citizens to support the Black Lives Matter movement (81 percent versus a national average of 51 percent). However, they’re less progressive when it comes to issues such as gay rights—black Protestants are considerably less likely than their white counterparts to support gay marriage. Young even admits that wokeness has “made converts within the established Churches, particularly the Church of England.”

Kisin, Murray, Peterson, and other figures who decry the religious aspects of contemporary progressivism are making an implicit (and sometimes explicit) claim: that the restoration of traditional faith would keep other forms of ideological commitment in check. But there’s a long history of Christian compatibility with a vast range of social and political movements—some good, some bad.

Many Nazis were Christians, and there were strong links between Catholicism and fascism in Europe during World War II. But some priests and other religious leaders resisted the Nazis, while the Western countries that fought fascism were predominantly Christian. In the early United States, Christianity was used to justify slavery. But John Brown’s Christian faith led him to wage war on slavery, and many early abolitionists (such as William Wilberforce) were evangelical Christians. During the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King Jr. and other leading figures in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference invoked Christianity to oppose racism and advocate for freedom and equality. But secularists like Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph were instrumental in this movement as well.

European powers rationalized their imperialist domination of countries in Africa and Asia with the belief that they were bringing Christian civilization to the world. The United States did the same in the Western hemisphere with the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. Yet many theologians in Latin America developed liberation theology in opposition to colonialism, racism, and other forms of oppression. Christianity is embraced by conservatives and libertarians who believe the Bible teaches thrift and personal responsibility. But it’s also embraced by progressives who think the central message of equality in the eyes of god is an argument for redistributive policies and greater support for the poor. The abandonment of religion isn’t a prerequisite for fervent commitment to any political cause or movement—including “wokeism.”

No matter how exhaustively the word “religion” is redefined, there’s plenty of evidence that secularization has taken place across the Western world. But there’s far less evidence for the opportunistic claim that this shift is responsible for the emergence of another socio-political movement. Those who say otherwise may have a “god-shaped hole” in their own lives, but they shouldn’t assume that everyone else suffers from the same affliction. More and more commentators are attempting to resuscitate religion under the guise of anti-woke politics, but they’re just exchanging one dogma for another.

[ Via: https://archive.is/PAij8 ]

==

The solution to the problems caused by one religion is not another religion.

#Matt Johnson#New Atheism#Konstantin Kisin#cult of woke#wokeism#wokeness as religion#woke#decline of religion#empty the pews#rise of the nones#god shaped hole#religion#dogma#woke dogma#religious dogma#atheism#religion is a mental illness

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kill your Primarchs

When I first heard about this I thought it was a terrible idea. I still do, but I’ve decided to have more complicated feelings about it.

Let’s talk about the idea of heroes, and Rationalism, and maybe New Atheism a bit.

So my gripe with this is to do with what the primarchs represent in Warhammer 40,000. Specifically in the 41st Milennium that is, I’m not talking about the Horus Heresy. I think this image here is an important casting off point to discussing it:

It’s got two heads but only one eye. The head facing to the right, the future, is blinded. The Aquila, and by extension the Imperium, can only look to the past. The Imperium’s whole schtick is that it’s a crumbling beaureaucratic organisation, mired in the past. Everything about the Imperium, from the beatification of genetically enhanced super-soldiers, to the religious observance of what are basically procedural documents in order to keep technology running, is geared towards the glorification of a near-forgotten and mythical past.

Before GW started resurrecting Primarchs, they and the Emperor held the status of ancient Heroes in that mythical past. The early descriptions of the Great Crusade and the Horus Heresy in the original Rogue Trader rulebook are really vague, as befits something that’s supposed to have happened ten thousand years before the current setting. It’s an age of myth, its heroes are long gone. This is what the great hero of the Imperium looks like in the 41st Milennium, according to the 1st edition rulebook:

I’m sorry but that’s a corpse.

Maybe you think the Traitor Legions are lying when they call him the Corpse Emperor but I really think the subtext in early Warhammer 40,000 is that the Imperium has managed to hold on to the corpses of some of their ancient heroes and interred them in machines that require an enormous investment of resources (a thousand psykers’ souls a day in the Emperor’s case) to run, in a futile exercise to cling on to the glories of the past. It’s true of the Emperor’s Golden Throne, it’s true of Roboute Guilliman’s stasis machine, and it’s true of the rumours that Lion El’ Jonson was lying somewhere under Caliban convalescing for all that time.

It’s felt like there’s been a drive among 40K fans and Games Workshop themselves to move Space Marines away from the hidebound traditionalism of the Imperium and make them more ‘genuinely’ heroic.The problem is that it’s exactly this heroism that ties them into the Imperium’s traditions. Space Marines are important to the Imperium in the same way Siegfired and other figures from Germanic myths (and Wagner’s operas) were important to the Nazis. Fascist ideology venerates heroic warrior figures to engender a culture that is comfortable with war.

When the Warhammer 40,000 lore didn’t make it clear whether these heroes of the Imperium’s past were dead or alive, but carried the subtext that they were dead, and the Imperium was wasting an enormous amount of resources on keeping them in a sort of un-life, it expressed the futility of this kind of hero-worship. If you start bringing them back, you communicate the idea that it wasn’t futile, and maybe that it was worth slaughtering all those psykers, and maybe that we should revere these bio-engineered sort-of-people as heroes.

And like, no. This is the image that’s always expressed the essence of *Space Marines* to me.

But then I started reading about Roboute Guilliman and apparently he’s the most logical, the most rational of the Primarchs, and I get the sense that in a lot of people’s minds this means he’s the most equipped to save the Imperium, whether from itself or everything outside it is unclear. But I think it’s interesting that according to this new lore he’s supposed to have woken up, seen what the Imperium’s become, and been totally apalled by it. Not by the genocide, of course, but by the fact that they’ve turned the Emperor into a god and the Primarchs into his angels. So he went and had a *conversation* with the Emperor, then turned around and started the genocide all over again, with a whole new crusade.

I’m going to talk about the 11th of September 2001 now, because it’s had consequences we’re only now starting to realise, and I think it definitely had consequences for Warhammer 40,000.

So, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens and other reprobates had been doing the rounds before 2001, but their movement really found its feet in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. Much of the Anglosphere and the West in general constructed an ideological divide between us and the Islamic world, where the West was civilised, rational and free, while the East was mired in superstition, religiosity and authoritarianism. In this context, a movement that characterised all religion as barbaric and anti-intellectual found itself in very fertile ground. For many people in the West, the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon could be dismissed not as retalliation for Western Imperialism, but as the deluded actions of religious fanatics. Rationalism and superstition were set up as ideological opponents, and rationalism was assumed to stand up for other values like liberty, intellectual freedom and human rights.

Horus Rising, the first of the Horus Heresy series, was released in 2006, the same year as Dawkins’ The God Delusion and the year before Hitchens’ God is not Great. Not much had been written about the Great Crusade or the Horus Heresy before this, and the idea that the Crusade had been an attempt by the Emperor to spread the light of reason into the galaxy first appeared in the lore at this point. In hindsight it’s pretty hard not to see this as a response to the post September 11 environment.

So, where the Space Marines of 1st editionhad been a bunch of psychopaths given genetic engineering and combat drugs, by 2006 you had the idea that their original function had been a sort of idealistic rationalism that was to make the galaxy a better place without religion, but that maybe some of them had fallen into superstition since then. Since then there’s maybe been a growing sense that Space Marines don’t really believe that the Emperor is a god and consider all of this a bit embarrassing.

So then you get a guy who’s been brought back to life, who was there with the Emperor during the crusade, he’s the one son who most embodies the Rationalist ideology that Games Workshop decided would drive the Great Crusade when the zeitgeist of the early 2000s taught that that ideology would lead to all good things.

And the reason he’s shocked by what the Imperium’s become isn’t because they sacrifice a thousand psykers a day to feed the Golden Throne, or because of the constant expansionist wars, or the genocide, it’s because they’re a bit religious about it.

And this is why my feelings about it are complicated. We’ve all been a bit concerned about whether Warhammer 40,000 is satire since Games Workshop released that statement, but I think this is good satire, and I don’t think they meant to do it. Christopher Hitchens, the poster boy of rationalism, supported the invasion of Iraq, he supported torturing prisoners until he tried water boarding for himself. In many ways the rationalism of the New Atheist movement was nothing more than a justification for Western Imperialism, and I think it’s interesting what Robout Guilliman’s rationalist genocide in the 41st Milennium has to say about that.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religion- Christianity, Mormonism, Judaism, Islam, Krishna, Hinduism, Buddhism, Wicca, Psychics, Tarot Cards, Spiritualism, The Law of Attraction, Magic, Ancestral Worship- all lack sufficient evidence enough to be taken seriously, or for us to waste our time on. Our time is limited, and you can choose what ever the fuck you want to do with the time you have, but you can at least do a little something that makes the world a little better than the way you found it.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Cited from the article:

“In retrospect, it’s unsurprising that a lot of New Atheism devolved into reactionary, antifeminist, and even white supremacist thought, because it was never really about the things it claimed to be about. The dominant affect of New Atheism wasn’t humility, or reflexivity, or curiosity, all the things one truly needs to improve intellectually. It was smugness.“

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#scaramouche#wanderer#genshin impact#right libertarian#objectivism#classical liberalism#fiscal conservatism#political philosophy#atheism#new atheism#the wanderer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

0 notes

Video

youtube

(via Darwin's Faith: The Religion of the New Atheism) In what do you place your confidence? Do you scoff at faith? Are you a rational being who doesn’t need faith? Are you delusional? A critique of Darwin’s (and Dawkins’) faith.

0 notes

Text

Source

This should never have been a thing

#religion#atheist#atheism#Christianity#prisons#abolish prisons#criminal justice#government#the left#news#current events

13K notes

·

View notes

Text

Atheism

New Post has been published on https://hazirbilgi.com/what-is-atheism-features-of-atheism/

Atheism

What is atheism? Features of atheism

Atheism is a philosophical system of thought that has existed since ancient times, has nothing to do with religions and does not accept the existence of God. Derived from the Greek word theos (god) and translated into English as theism , this word was given the name atheism with the adjective (a), which is a prefix and gives the meaning of negativity. However, this concept, which is expressed as godless if it is translated into Turkish, cannot be fully explained.

This system of thought is clearly separated from Pantheism , Deism , Agnosticism and Theism , where different views on the existence or non-existence of god are adopted . In the atheist thought system, there is no discussion of religion types and the existence of religions, and philosophy is all about the concept of god. At the same time, religious spiritual beings and metaphysical beliefs are not included in the philosophy of atheism.

The history of atheism and its first representatives

When the history of atheism is examined, it is seen that this idea coincides with the first emergence of the concepts of god and religion. The first known atheist in history, BC. Diagoras, who lived in the 5th century and questioned beliefs intensely. At the same time, Buddhism and Hinduism are among the schools close to atheism, as materialism is brought to the fore.

Another known atheist thinker in history is Socrates, who lived during the Ancient Greek period. In the Greek society, which is known to attach great importance to the gods, Socrates was executed because he was thought to have inspired the gods.

Democritus, one of the pioneers of philosophical movements, believes only in the existence of matter, unlike spirits, and is another representative of this thought. Epicurus, one of the first atheists, who explained in different ways but the only common point was the absence of god, also defended matter just like Democritus, but he defended the idea that even if god exists, he cannot interfere with nature and people.

Along with the religion of Christianity, atheists who did not accept the existence of God were punished severely and their number decreased, especially during the Roman Empire. However, this situation began to change with the Renaissance, and atheistic thought began to revive and multiply in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The most important and known atheist representative of the period; The author of the book Common Sense, which was also translated into Turkish, is the French priest Jean Mislier. In the 19th and 20th centuries, which are the next period, especially German thinkers and philosophers emerge as representatives of atheism.

Arthur Schopenhauer, Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx, Jean Paul Sartre, Friedrich Nietzsche and Friedrich Engel. Atheism, which was first brought to a political line with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel, was adopted by Enver Hoxha, who was also the leader of Albania in this period, and it was declared that the country was an atheist country. As a result of this development, the first atheist state order in history was established and officially declared.

What are the characteristics of atheism?

There are many different types of atheism and the common point of all these types is that they deny the existence of god. The most distinctive feature of this system of thought is that it does not deal with religions, metaphysics and mystical issues, and the only subject it deals with is the existence of God.

In atheist thought, the characteristics of religions are examined instead of religions being good or bad, but not just a creator. And another distinguishing point from different beliefs is that only matter exists and the subject of discussion consists of materialistic contents.

What are the types of atheism and who are its representatives?

The idea of atheism has manifested itself in many genres as a result of developments and changes in history and has continued with minor differences. Thought, which is generally divided into two different branches as practical and theoretical, is explained with two different definitions.

Practical atheism

practical atheism ; It is a person’s life as if there is no god and he does not value religious beliefs and mystical thoughts. According to this view, since God does not already exist, there is no need to enter into discussions about this concept. Its most important representatives are the famous German thinkers Friedrich Nietzsche and Ludwig Feuerbach.

Theoretical atheism

Theoretical atheism is the name given to the idea that various researches and theses are put forward to refute the existence of god as well as to ignore the existence of god. Despite the fact that practical atheism does not value; religions, religious beliefs and theories such as life after death and belief in the afterlife have been included in the system to be refuted. In this type of atheism, ideas such as deism and pantheism that accept the existence of god are not included.

atheism,atheism definition,is atheism a religion,atheism vs agnostic,is atheism dead,reddit atheism,atheism symbol,types of atheism,new atheism,atheism meaning,christian atheism,atheism ap human geography,atheism a religion,atheism antonyms,atheism and morality,atheism and human nature,atheism afterlife,atheism ap human geography definition,agnostic atheism,agnostic vs atheism,

#agnostic atheism#agnostic vs atheism#atheism#atheism a religion#atheism afterlife#atheism and human nature#atheism and morality#atheism antonyms#atheism ap human geography#atheism ap human geography definition#atheism definition#atheism meaning#atheism symbol#atheism vs agnostic#christian atheism#is atheism a religion#is atheism dead#new atheism#reddit atheism#types of atheism

1 note

·

View note

Text

youtube

The Four Horsemen: Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Atheism#"Four_Horsemen"

On 30 September 2007, Dawkins, Harris, Hitchens and Dennett met at Hitchens' residence in Washington, D.C., for a private two-hour unmoderated round table discussion. The event was videotaped and titled "The Four Horsemen"

[Ayaan] Hirsi Ali, originally scheduled to attend the 2007 meeting, later appeared with Dawkins, Dennett, and Harris at the 2012 Global Atheist Convention, where she was referred to as the "plus one horse-woman" by Dawkins. Robyn Blumner, CEO of the Center for Inquiry, described Hirsi Ali as the "Fifth" horseman.

#Richard Dawkins#Christopher Hitchens#Sam Harris#Daniel Dennett#atheism#new atheism#The Four Horsemen#religion#criticism of religion#religion is a mental illness#Youtube

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

“The New Atheism and the Problem of Evil.” Access this premium Bib Sac article by Apologetics Guy Dr. Mikel Del Rosario and Darrell Bock for free.

#ApologeticsWeek#Christian Apologetics#2022#New Atheism#Darrell Bock#Apologetics Guy#Mikel Del Rosario#PDF

0 notes