#middlemarch

Text

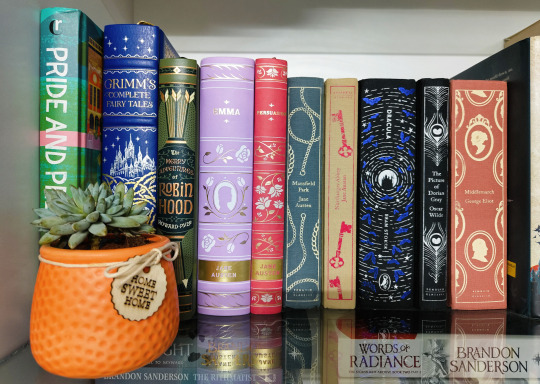

JOMP Book Photo Challenge

November 03, 2023 - Older than me

#jompbpc#justonemorepage#book stack#bookshelf#pride and prejudice#grimm's fairy tales#the merry adventures of robin hood#emma#persuasion#mansfield park#northanger abbey#dracula#the picture of dorian gray#middlemarch#classics#penguin clothbound classics#booklr#mypics#books#bookblr#read#books and plants

209 notes

·

View notes

Text

you were in the top 0.01% of listeners to that roar which lies on the other side of silence

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

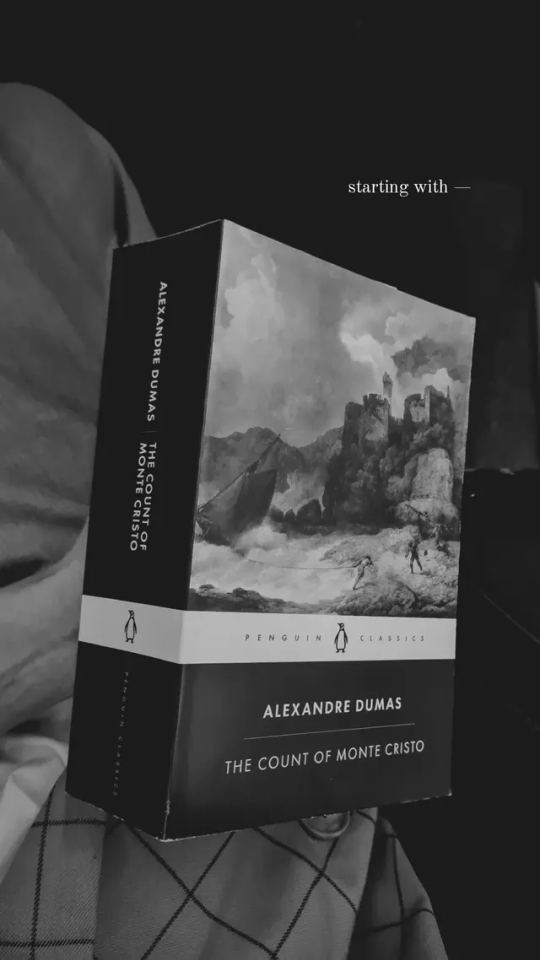

introducing one of my challenges/reading goals for next year (heavily inspired by emmie on youtube)

— after having an extremely mid reading year this year, i'm hoping to focus on quality over quantity in 2024. for me, this means reading a lot of bucket list books. i'm so excited to check off a couple of classic tomes from my tbr!!

i'll also be doing an in-depth analysis or review on my substack, and a highlight on my instagram for live updates (if anyone wants to join me, the schedule is above <3)

#classic tomes#literature aesthetics#books#book#bookish#bookblr#bookworm#bookstagram#dark academia#booklover#books and libraries#the count of monte cristo#alexandre dumas#the divine comedy#inferno#dante#classics#russian classics#fyodor dostoevsky#middlemarch#george eliot#metamorphosis#east of eden#studyblr#study space#study hard#study tips#study#study motivation#beige

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

She [...] looked at him as the garden flowers look at us when we walk forth happily among them in the transcendent evening light.

George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1871

324 notes

·

View notes

Text

And, of course men know best about everything, except what women know better.

- George Eliot, Middlemarch

#quotes#books#literature#lit#classics#academia#light academia#dark academia#chaotic academia#book#book quotes#quotation#George Eliot#Middlemarch#Historical Fiction#Fiction

85 notes

·

View notes

Note

what are your thoughts on tertius lydgate wrt marking shifts in discourses of medicine? his position in the novel fascinated me as someone who feels very strongly about the role of doctors in society, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts on the matter

YES lydgate rules so hard in my personal pantheon of doctor characters. sorry this has been in my inbox for a thousand years i had was rotating.

so first of all one of the things that makes 'middlemarch' interesting is that it's a historical novel. so, when george eliot creates a doctor character for the year 1829, writing from 40 or so years later, she's using him to comment on (her perception of) changes to medical science in britain over the course of several decades. so for instance, the fact that lydgate trained in edinburgh and paris tells us immediately that we're supposed to understand him not just as a member of a newly 'respectable' profession, but specifically as having a viewpoint that is informed by radical student politics (edinburgh) and conceptions of the doctor as a social reformer (paris) as well as the research traditions of raspail and bichat. indeed this is why lydgate's crusade in town includes his ideas about sanitation and public health; in contradistinction to the other physicians, he sees his medical and scientific authority as giving him the ability and responsibility to reform the town more broadly. like his parisian counterparts, lydgate clearly sees a link between, eg, cholera and more general social and political unrest. he fashions himself as someone who can doctor the social body as much as the individual patient; given his parisian training we can place him loosely in a social-hygienist context here.

lydgate is also a pretty early example in british literature of a doctor character who's presented as a) not a charlatan and b) heroic explicitly on the basis of his medical and scientific status. british medical practitioners were subject to a new licensure requirement in 1815 i believe (i'd have to double check this date i don't read as much in 19thc britain); 'middlemarch' was written around 1870 and set in 1829–32. so, for eliot, lydgate was genuinely part of a markedly new wave of physicians—men who were licensed (read: state-approved) and occupied a new social position. lydgate is also minor aristocracy, which is part of what makes it possible for him to scoff at the town's older physicians, but much of his social position in the town is accrued in conjunction with the newly and increasingly prestigious status of his profession. this is not really a character type that would have been plausible in a realist novel set in the same country a generation or two earlier.

eliot herself was married to a man of science and also kept abreast of medical and scientific ideas (for example, she was extremely interested in phrenology, an influence you can see throughout 'middlemarch'), and lydgate is very much a man of the times in this respect: he diagnoses george's scarlet fever in the early stage, for example, and refuses to dispense his own prescriptions or to take money from pharmacists. these, along with his emphasis on public health and sanitation measures, mark him as not just an idealist but someone whose medical practice was genuinely steeped in current principles of scientific and ethical reform. even his embrace of bichat's tissue theory, though presented somewhat vaguely, would have signalled to a reader familiar with recent anatomical theories that lydgate was not just a fashionable thinker (bichat died in about 1802, but his work came to popularity over the next 3-4 decades in england and france) but also a precise and naturalistic one, aligning himself with a research tradition that emphasised specific, local lesions as etiological agents (compare this to the brain-localisation ideas of the phrenologists).

ultimately, lydgate's tragedy is that his medical knowledge isn't matched by any social acuity, and his match with rosamond is dissatisfying for both of them. i don't read this as eliot condemning the aspirational early stages of lydgate's career; his mistakes are all made in the interpersonal arena, with both rosamond and the raffles affair. had he played these situations smarter, who knows what he may or may not have accomplished for the residents of middlemarch. instead, he ends the book as a successful but dissatisfied physician to the wealthy, in a position of financial security and medical specialisation but without the kind of moral or political status that he sought earlier in the book by presenting himself as both a social and medical reformer. eliot thus engages, i think, another new type of doctor character: lydgate at the end of the book still has no trace of the quackery or charlatanism that characterised many previous representations of doctors, but he's also been purged of the youthful idealism that pervaded the edinburgh and paris medical education he received. the social status he attains at the end of his life is based on his wealth and the general respectability of the medical profession; treating gout doesn't give him any higher prestige than that, and certainly not the kind of moral authority or fulfillment he wanted back in middlemarch.

so, and recognising that this sort of leaves aside a lot of the psychological nuance of the novel, lydgate's storyline gets at two of the major historical points eliot is interested in. first there's the changing status of british medicine and medical practitioners. lydgate begins the novel as the self-styled hero-reformer; experiences a social fall from grace that compounds with the resistance he already faces from the other town physicians for the threat he poses to their professional status; and ends as the consummate specialist, performing the same boring, lucrative work day in and day out for wealthy londoners (note also the use of gout here to indicate a high degree of moral lassitude and overconsumption among his patients, lol). secondly, and relatedly, there's a shift in class positions going on here. lydgate's initial position in middlemarch is as minor (not wealthy) nobility; by the end of the book he's in a newly high-status professional class, has gained more wealth (though ofc not enough for rosamond), and has been forced out of the countryside. this all tracks with both the expansion of cities generally in this period, and the strengthening of the middle class / petit bourgeois (consider the 1832 reform bill).

although eliot's own views about medicine were largely concordent with the kind of positivistic naturalism of her peers (see again her interest in phrenology), part of what she does with lydgate is, i think, intended as a warning: here's a confluence of forces that have turned an idealistic public health reformer into a dissatisfied man pursuing his personal material security at the direct expense of his philanthropic and altruistic aims. it's a success story for the medical profession in many ways (financially, reputationally) but also a tragedy in the eyes of anyone who believes that physicians ought to have more responsibility to their patients and their polities than their pocketbooks. we're meant to understand medicine as not just a personal curative, but potentially a socially enlightening force---but, only if its aspirations in this direction aren't hindered by the very forces turning it into a more respectable and lucrative career for the rising professional class.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

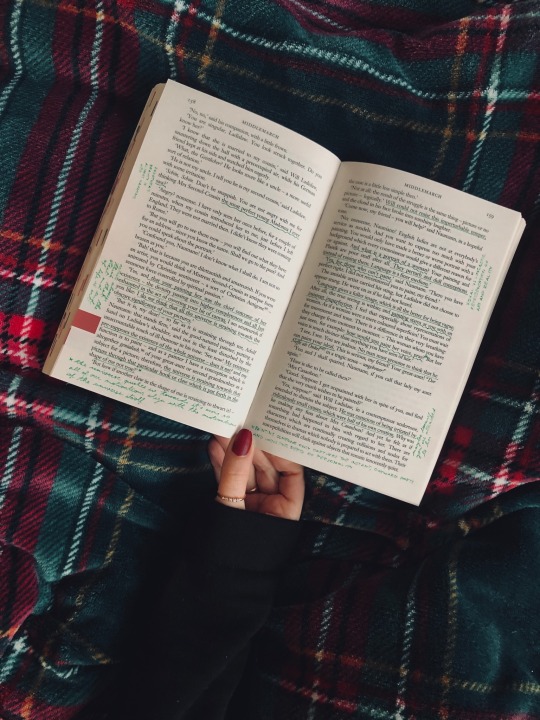

#marginalia#annotations#reading#books#booklover#booktok#studylbr#studyblr#studyinspo#george eliot#middlemarch#bookstagram#annotating books#bookworm

275 notes

·

View notes

Text

23/03/24

Homesick but bringing a book makes it easier

#aesthetic#academia aesthetic#chaotic academia#classic academia#dark acadamia aesthetic#dark academism#old aesthetic#romantic academia#soft academia#books & libraries#light academia moodboard#middlemarch#dublin#ireland

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

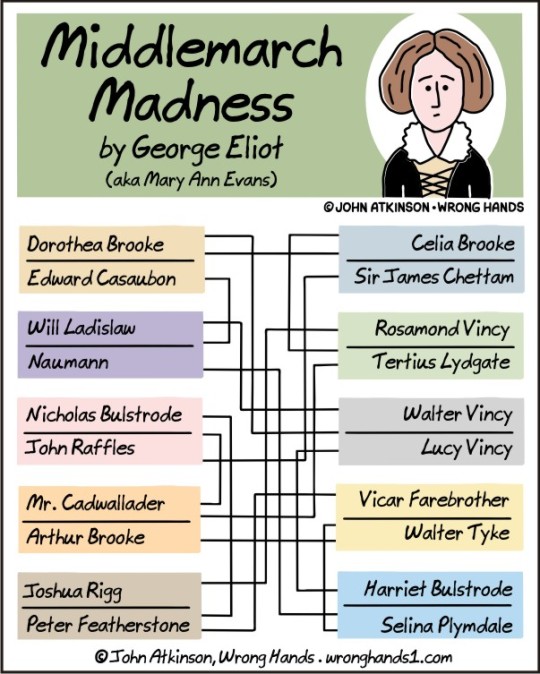

#middlemarch#george eliot#literature#books#reading#basketball#march madness#ncaa#sports#wronghands#john atkinson#webcomic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

this site needs more middlemarch content. honestly, how have we not all gone feral for middlemarch yet?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

the moral of Middlemarch is don't marry someone just because they're a hot weirdo who has a crush on you

44 notes

·

View notes

Note

Can you tell me about Middlemarch? I've been dying to read some George Elliot hehehe. I don't know why, but I'm quickly prepared for her to become one of my fav writers

Yes, of course!! I have absolutely adored George Eliot ever since I read Middlemarch a few years ago. I love the way she weaves a slow, careful narrative where little things appear so insignificant and yet so beautiful--a story where the importance lies not in the drama or the scale of the plot, but in the emotions and inner reflections of the characters. I also do love her style, from what I've read of her in English. Keep in mind, I did read Middlemarch entirely in the Russian translation, so I can't reflect or comment on the style of that novel specifically, but I am about 100 pages into Mill on the Floss in English. She does an incredible job at portraying the various accents and speech patterns from different layers of society in a way that doesn't feel over the top, and is instead authentic and genuine to the way the characters are developed. She also has many complicated, human female heroines, which is something that is really special in novels from that period (and, arguably, still :( lol). I love everything about George Eliot--her life is super interesting too, and there are so many books of hers that I can't wait to read in the near future! I am especially impatient to read Silas Marner, Daniel Deronda, and Romola (which is actually based on one of my favorite painters of all time, Artemisia Gentileschi).

I hope this helps, and I hope you enjoy the experience of George Eliot's writing. It's slow, and profound, and just really truly lovely. :) I would love to hear some of your thoughts while/after you are reading!

And I'll end on my absolute favorite Middlemarch quote:

"[...] for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs."

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Started the famous J. Robert Oppenheimer biography yesterday, the one that took thirty years to write and won the Pulitzer Prize. Here’s a few discoveries so far:

• His absolute favourite book as an adolescent was, impressively i think, George Eliot’s Middlemarch

• His father met his mother at an art gallery in New York and he fell instantly in love with her; we’re given a sample of their love letters and I must admit … (sniff). So that’s nice; though it’s curious to think how one of the fundamental precursors of The Manhattan Project has a direct common ancestry to fine art.

• He grew up with an unbelievable collection of artwork around him at his home, including a Rembrandt sketch, several Van Goghs and Cézannes.

• At twelve years old he corresponded regularly with leading geologists in the States; after a time, not knowing his age, several of them nominated his membership into the Geological Society and invited him to give the traditional inaugural lecture. When he arrived everyone rolled about with laughter (at their own foolishness, it seems) and amazement at his precocity. They found a box for him to stand on at the dais and little Oppenheimer gave, to all accounts, a fine lecture.

more to come (not with a bang but a whimper, etc.,)

#j robert oppenheimer#middlemarch#george eliot#van gogh#rembrandt#paul cezzane#oppenheimer#american prometheus#personal notes#fine art#the manhattan project#n.

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

[...] she could feel alone with the earth and sky, away from the oppressive masquerade of ages, in which her own life too seemed to become a masque with enigmatical costumes.

George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1871

170 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The memory has as many moods as the temper, and shifts its scenery like a diorama.

George Eliot, Middlemarch

219 notes

·

View notes