#michael clune

Photo

On Novocain

“I’ve been clean for over twenty years.”

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2023/03/06/on-novocain/

0 notes

Text

"VANITY FAIR" (2018) Review

“VANITY FAIR” (2018) Review

When I had first heard that the ITV channel and Amazon Studios had plans to adapt William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1848 novel, “Vanity Fair”, I must admit that I felt no interest in watching the miniseries. After all, I had already seen four other adaptations, including the BBC’s 1987 production. And I regard the latter as the best version of Thackeray’s novel I had ever seen.

In the end, my curiosity got the best of me and I decided to watch the seven-part miniseries. In a nutshell, "VANITY FAIR" followed the experiences of Rebecca "Becky" Sharp, the social climbing daughter of an English not-so-successful painter and a French dancer in late Georgian England during and after the Napoleonic Wars. The production also told the story of Becky's school friend and daughter of a wealthy merchant, Amelia Sedley. The story begins with both young women leaving Miss Pinkerton’s Academy for Young Ladies. Becky managed to procure a position as governess to Sir Pitt Crawley, a slightly crude yet friendly baronet. Before leaving for her new position, Becky visits Amelia's family. She tries to seduce Jos Sedley, Amelia's wealthy brother and East India Company civil servant. Unfortunately George Osborne, a friend of Jos and son of another wealthy merchant, puts a stop to the budding romance.

While working for the Crawleys, Becky meets and falls in love with Sir Pitt’s younger son, Captain Rawdon Crawley. When Sir Pitt proposes marriage to Becky, she shocks the family with news of her secret marriage to Rawdon. The couple becomes ostracized and ends up living in London on Rawdon’s military pay and gambling winnings. They also become reacquainted with Amelia Sedley, who has her own problems. When her father loses his fortune, George's own father insists that he dump Amelia and marry a Jamaican heiress. George refuses to do so and thanks to his friend William Dobbin's urging, marries Amelia. Mr. Osborne ends up disinheriting George. However, the romantic lives of Becky and Amelia take a backseat when history overtakes them and their husbands with the return of Napoleon Bonaparte.

I wish I could say that the 2018 miniseries was the best adaptation of Thackery's novel I had seen. But it is not. The production had its . . . flaws. One, I disliked its use of the song "All Along the Watchtower" in each episode's opening credits and other rock and pop tunes during the episodes' closing credits. They felt so out of place in the miniseries' production. Yes, I realize that a growing number of period dramas have doing the same. And quite frankly, I detest it. This scenario barely worked in the 2006 movie, "MARIE ANTOINETTE". Now, this use of pop tunes in period dramas strike me as awkward, ham-fisted, unoriginal and lazy.

I also noticed that producer and screenwriter Gwyneth Hughes threw out the younger Pitt Crawley character (Becky's brother-in-law), kept the Bute Crawley character and transformed him from Becky Sharp's weak and unlikable uncle-in-law into her brother-in-law. Hughes did the same with the Lady Jane Crawley and Martha Crawley characters. She tossed aside the Lady Jane character and transformed Martha from Becky's aunt-in-law to sister-in-law. Frankly, I did not care for this. I just could not see characters like Bute and Martha suddenly become sympathetic guardians for Becky and Rawdon's son in the end. It just did not work for me. I have one last problem with "VANITY FAIR", but I will get to it later.

I may not regard "VANITY FAIR" as the best adaptation of Thackery's novel, I cannot deny that it is first-rate. Gwyneth Hughes and director James Strong did an excellent job of bringing the 1848 novel to life on the television screen. Because this adaptation was conveyed in seven episodes, both Hughes and Strong were given the opportunity retell Thackery's saga without taking too many shortcuts. The miniseries replayed Becky Sharp's experiences with the Sedley family, George Osbourne, and the Crawley family in great detail. I was especially impressed by the miniseries' recount of Becky and Amelia's experiences during the Waterloo campaign - which is the story's true high point, as far as I am concerned. Also, this adaptation had conveyed George's experiences during Waterloo with more detail than any other adaptation I have seen.

Aside from the Waterloo sequence, there were other scenes that greatly impressed me. I really enjoyed those scenes that featured the famous Duchess of Richmond's ball in the fourth episode, "In Which Becky Joins Her Regiment"; Becky's attempts to woo Jos Sedley in the first episode, "Miss Sharp In The Presence Of The Enemy"; the revelation of Becky's marriage to Rawdon Crawley in "A Quarrel About An Heiress"; and her revelation to Amelia about the truth regarding George in the final episode, "Endings and Beginnings". There were people who were put off that the series did not end exactly how the novel did - namely the death of Jos, with whom Becky had hooked up in the end. I have to be honest . . . that did not bother me. However, I was amused that Becky's last line in the miniseries seemed to hint that Jos' death might be a possibility in the near future.

The production values for "VANITY FAIR" struck me as quite beautiful. I thought Anna Pritchard's production designs did an excellent job in re-creating both London, the English countryside, Belgium, Germany, India and West Africa between the Regency era and the early 1830s. Not only did I find the miniseries' production values beautiful, but also Ed Rutherford's cinematography. His images struck me as not only beautiful, but sharp and colorful. I would not say that Lucinda Wright and Suzie Harman's costume designs blew my mind. But I cannot deny that I found them rather attractive and serviceable for the narrative's setting.

One of the production's real virtues proved to be a very talented cast. "VANITY FAIR" featured some solid performances from it supporting players. Well . . . I would say more than solid. I found the performances of Robert Pugh, Peter Wight, Suranne Jones, Claire Skinner, Mathew Baynton, Sian Clifford, Monica Dolan, and Elizabeth Berrington to be more than solid. In fact, I would say they gave excellent performances. But they were not alone.

Michael Palin, whom I have not seen in a movie or television production in years, gave an amusing narration in each episode as the story's author William Makepeace Thackeray. Ellie Kendrick gave a very poignant performance as Jane Osborne, who seemed to be caught between her loyalty to her bitter father and her long-suffering sister-in-law. Simon Beale Russell gave a superb, yet ambiguous portrayal of the warm and indulgent John Sedley, who also had a habit of infantilizing his family. Frances de la Tour was deliciously hilarious and entertaining as Becky Sharp's aunt-in-law and benefactress Lady Matilda Crawley. I could also say the same about Martin Clunes, who gave a very funny performance as the crude, yet lively Sir Pitt Crawley. One last funny performance came from David Fynn, who gave an excellent portrayal of the vain, yet clumsy civil servant, Jos Sedley. Anthony Head gave a skillful performance as the cynical and debauched Lord Styne. I thought Charlie Rowe was superb as the self-involved and arrogant George Osborne. Rowe, whom I recalled as a child actor, practically oozed charm, arrogance and a false sense of superiority in his performance as the shallow George.

I have only seen Johnny Flynn in two roles - including the role of William Dobbin in this production. After seeing "VANITY FAIR", it seemed that the William Dobbin role seemed tailored fit for him. He gave an excellent performance as the stalwart Army officer who endured years of unrequited love toward Amelia Sedley. Tom Bateman was equally excellent as the charming, yet slightly dense Rawdon Crawley. At first, I thought Bateman would portray Rawdon as this dashing, yet self-confident Army officer. But thanks to his performance, the actor gradually revealed that underneath all that glamour and dash was a man who was not as intelligent as he originally seemed to be. Amelia Sedley has never been a favorite character of mine. Her intense worship of the shallow George has always struck me as irritating. Thanks to Claudia Jessie's excellent performance, I not only saw Amelia as irritating as usual, but also sympathetic for once.

Television critics had lavished a great deal of praise upon Olivia Cooke as the sharp-witted and manipulative Becky Sharp. In fact, many have labeled her performance as one of the best versions of that character. And honestly? I have to agree. Cooke was more than superb . . . she was triumphant as the cynical governess who used her charms and wit in an attempt to climb the social ladder of late Georgian Britain. I would not claim that Cooke was the best on-screen Becky I have seen, but she was certainly one of the better ones. I have only one minor complaint - I found her portrayal of Becky as a poor parent to her only son rather strident. Becky has always struck me as a cold mother to Rawdon Junior. But instead of cold, Cooke's Becky seemed to scream in anger every time she was near the boy. I found this heavy-handed and I suspect the real perpetrator behind this was either screenwriter Gwyneth Hughes or director James Strong.

I have a few complaints about "VANITY FAIR". I will not deny it. But I also cannot deny that despite its few flaws, I thought it was an excellent adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray's novel. Actually, I believe it is one of the better adaptations. "VANITY FAIR" is also one of the best period dramas I have seen from British television in a LONG TIME. And I mean a long time. Most period dramas I have seen in the past decade were either mediocre or somewhere between mediocre and excellent. "VANITY FAIR" is one of the first that has led me to really take notice in years. And I have to credit Gwyneth Hughes' writing, James Strong's direction and especially the superb performances from a first-rate cast led by Olivia Cooke. It would be nice to see more period dramas of this quality in the near future.

#vanity fair#william makepeace thackeray#michael palin#olivia cooke#tom bateman#johnny flynn#claudia jessie#james strong#anthony stewart head#charlie rowe#ellie kendrick#napoleonic wars#period drama#period dramas#costume drama#suranne jones#history#frances de la tour#simon beale russell#martin clunes#elizabeth barrington#monica dolan#david flynn#claire skinner#sian clifford#robert pugh#martin baynton#richie campbell

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Michael W. Clune writing in First Things. Which is intriguing, because Clune seems to have unrestricted access to left-lib media and doesn't need to publish in First Things. First Things is surely more cancellable even than Compact (I refer to my recent conversation with Emmalea Russo). I have no great opinion on Clune's substantive argument against drug decriminalization—an argument I first encountered in its current form when I reviewed Sam Quinones's The Least of Us for Tablet (Tablet is problematic but possibly even less cancellable than Compact)—and will only say this.

By instinct, I fear heavy-handed state interdictions of individual desire, even though I acknowledge that a broadly "conservative" approach to individual desire is probably best for most people in most cases (I include myself). A liberal or libertarian civilization works best—or only works at all—when its independent institutions can best be trusted to educate our desire well enough that the state doesn't have to manage it for us. This is why, to return to grounds more familiar to me than drug policy, it was such a huge mistake for arts education to take too sharp a turn toward popular culture or "easy pleasures." The Silent and Boomer generations who instituted this turn—including the aforementioned Sontag and Paglia—were themselves able to appreciate popular culture "safely," which is to say with tremendous sensitivity and intellect, because their own desires had been reared on high culture. It was as if someone who'd grown up sipping a mouthful or two of dry wine with dinner began to throw keggers for nine-year-olds. This is an unashamedly transcendental view. The YouTube and TikTok pop mystics' "higher self" is a better guide to desire and action than what Clune calls his "deepest self," since I take the deep self to be a reptile or protozoan (for insight here see two narratives I discussed, again, with Emmalea: Dante's Purgatorio and Chayefsky and Russell's Altered States).

I am curious about how Clune's "conservative" vision of desire in First Things correlates with "Bernhard's Way," his 2013 nonsite essay that I judged perhaps the most important piece of literary theory written in the 2010s. "What would a commitment to art that has passed through the postmodern critique of art look like?" Clune asks. His answer—that society will always instrumentalize art, usually for corrupt ends, just as postmodernism taught us; that art's purpose is therefore the enhancement of the artist's self rather than any direct service to society, this as against postmodernism's stupid quest to render art politically correct—looks, in the divine light of the First Things essay, like a redescription of art as prayer or meditation: the silencing inside the soul of the social self, of the mere ego, so that the higher self or just the higher tout court may speak in its place.

Bernhard’s belief that authorship entails a transformation of the writer derives much of its plausibility from the testimony of centuries of authors who declare themselves transformed by writing, and by the conventions that associate artistic speech with a quasi-divine apotheosis of the voice.

Or, as another writer concerned with first (and last) things prayed, "Teach us to sit still."

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The basic move of the politics of exclusion is to say that a given system — of human rights, citizenship, gender, race, law, public health — gains form by excluding someone or something. Not only is the integrity of the system paradoxically dependent on what it excludes, but the excluded factor also represents a privileged perspective for understanding the workings of that system, which is typically concealed from the included.

Readers of this review will likely be familiar with this logic. So, what’s wrong with it? Anker argues that, as a mode of analysis, the paradox of exclusion suffers from several basic flaws. First, it isn’t the most obvious approach to take if you’re interested in practical social justice. The point, one might feel, of critiquing exclusion and oppression is to end exclusion and oppression. Yet the experience of oppression is, from the perspective of the paradox of exclusion, “ennobling.” The “liberatory ethos of paradox,” with its endlessly reiterated “call to ‘give voice to exclusion,’” routes attention away from practical solutions to oppression and towards reaping the supposed benefits of attending to the perspective of the excluded.

Throughout her book, Anker suggests that theory’s fascination with paradox draws its energy from religious and literary conceptions of paradox embedded within earlier versions of the humanities. This accounts for the otherwise curious “worship of paradox” she notes in the politics of exclusion. But if Christianity offers a framework in which it makes sense to venerate the suffering of the poor who will always be with us, the same cannot be said for a supposedly secular theory, which, if it’s really interested in social justice, should be oriented towards ending suffering. Similarly, if great literary works have the capacity to cause us to fixate on paradoxes of action, such a fixation looks like a liability when the theorist’s interest is in forms of action that might counter the effects of racism, homophobia, or exploitation.

The second problem with paradox is that, by enclosing a complex social problem within a simple, endlessly portable contradiction, it obviates the need for fine-grained analysis of particular contexts, histories, and values: “[T]he logic of paradox […] short circuit[s] the types of reason-based, evaluative, comparative labor on which, it should go without saying, intellectual life depends.” Anker, an English professor trained as a lawyer, is especially sensitive to the bizarre effects of applying the paradox of exclusion to the study of the law. For example, she discusses the tendency among humanists to leap from the fact that the law sometimes excludes to the idea that the law always and constitutively excludes, “creating the illusion that an unbroken narrative connects slavery to the prison-industrial complex.”

It is, of course, this rote simplicity of thinking via paradox that has made theory so attractive to and recyclable by nonacademic institutions. For Anker, this quality renders it inappropriate for academic disciplines that should prize rigorous and expert analysis. Humanists, she suggests, shouldn’t already know what we’re going to find in a given text or space before we encounter it. Yet, as she shows, the logic of paradox preformats a bewildering array of objects of humanistic inquiry. Her herculean labor in reading many hundreds of works of theory shows the extent to which humanistic research often consists of dumping the contents of a given historical period or archive into the paradox machine and standing back while it does its work.

Given that literally anything can be said to be constituted by what it excludes, and that any solution to a given paradoxical situation will have its own disabling paradoxes, paradox-thinking represents the “cultivated resistance to a praxis theorizable in affirmative, serviceable, constructive terms.” Paradoxes “are geared to neutralize substantive propositions, rather than to facilitate reasoning aimed at the positing of practical game plans or normative goals.” Anker offers an amusing précis of Agamben’s body of work — in which every institution becomes, through the alchemy of paradox, a more or less serviceable replica of Auschwitz — as the reductio ad absurdum of a tendency she also finds in more circumspect (or less consistent) theorists.

In analyzing theory in terms of a style of thought, and identifying this style with paradox, Anker illuminates both why theory has migrated so effectively beyond the academy and also how its self-replicating endlessness gives a startling large-scale intellectual uniformity to the pronouncements of elite institutions and right-wing conspiracists alike. Unlike some earlier versions of the dissent from theory, Anker doesn’t attack “critique” as such. Rather, it is the tendency to dumb down critique through overuse of a one-size-fits-all logic of paradox that concerns her. We should strive to loosen paradox’s hold on us and open ourselves to theoretical paradigms that enable attention to values occluded by thinking exclusively in paradox, such as “[n]oncontradiction, harmony, coherence, stability, unity, clarity, resolution, perseverance, continuity.”

Michael W. Clune, The Paradox Paradox: On Elizabeth S. Anker’s “On Paradox”

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of Our Aircraft Is Missing is a 1942 British war film, mainly set in the German-occupied Netherlands. It was the fourth collaboration between the British writer-director-producer team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

On its way back from a raid on the city of Stuttgart, a British bomber is shot down over Nazi-held Holland. Parachuting into Dutch farmlands under cover of darkness, the six-member crew connects with members of the local resistance, who shelter the Brits from their Nazi inquisitors as they make their way towards freedom.

The film stars Eric Portman, Bernard Miles, Googie Withers, Pamela Brown, Peter Ustinov (in his film debut), Alec Clunes, Hay Petrie, Robert Helpmann, Hugh Williams and Godfrey Tearle.

#eric portman#bernard miles#googie withers#one of our aircraft is missing#1940s#godfrey tearle#hugh williams#robert helpmann#hay petrie#alec clunes#peter ustinov#pamela brown#powell and pressburger#michael powell#old britain#emeric pressburger#holland#the netherlands#ww2#second world war#world war two

0 notes

Note

Leechs! Michael W. Clune's White Out had a second printing this year and it is mandatory junkie scholar reading if you haven't already. It's an memoir of his heroin addiction while getting his doctorate at johns hopkins in the late nineties and easily some of the best writing on addiction and memory you'll encounter.

obsessed i will have to check it out...

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1893 – Birth of IRA Volunteer, Richard ‘Dick’ McKee, at Phibsborough Rd in Dublin.

McKee became an apprentice in the publishing business at Gill & Son, Upper O’Connell Street, and then a compositor. McKee was a prominent member of the IRA. He was also friend to some senior members in the republican movement, including Éamon de Valera, Austin Stack and Michael Collins. Along with Peadar Clancy and Conor Clune, he was killed by his captors in Dublin Castle on 21 November 1920, a…

View On WordPress

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

One Of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942) Full Movie English War Film Classic

One of Our Aircraft Is Missing is a 1942 British black-and-white war film, mainly set in the German-occupied Netherlands. The crew of an RAF Vickers Wellington bomber are forced to bail out over the Netherlands near the Zuider Zee after one of their engines is damaged during a nighttime raid on Stuttgart. Five of the six airmen find each other; the sixth goes missing, According to Kinematograph Weekly the film was one of the most popular at the British box office in 1942 and it gets a 100% from Rotten Tomatoes. Cast Hugh Burden as John Glyn Haggard, pilot of B for Bertie Eric Portman as Tom Earnshaw, the second pilot Hugh Williams as Frank Shelley, observer/navigator Emrys Jones as Bob Ashley, wireless operator Bernard Miles as Geoff Hickman, front gunner Godfrey Tearle as Sir George Corbett, rear gunner Googie Withers as Jo de Vries Joyce Redman as Jet van Dieren Pamela Brown as Els Meertens Peter Ustinov as Priest Alec Clunes as Organist Hay Petrie as Burgomaster Roland Culver as Naval Officer David Ward as First German Airman Robert Duncan as Second German Airman Selma Vaz Dias as Burgomaster's wife (as Selma Van Dias) Arnold Marlé as Pieter Sluys Robert Helpmann as De Jong Hector Abbas as Driver James B. Carson as Louis Willem Akkerman as Willem Joan Akkerman as Maartje Peter Schenke as Hendrik Valerie Moon as Jannie John Salew as German Sentry William D'Arcy as German Officer Robert Beatty as Sgt. Hopkins Michael Powell as Despatching Officer (also a director-producer) Stewart Rome as Cmdr. Reynold You are invited to join the channel so that Mr. P can notify you when new videos are uploaded, https://www.youtube.com/@nrpsmovieclassics

0 notes

Text

youtube

Rich Clune vs. Michael Pezzetta December 28, 2019.

0 notes

Text

Virginia Mori for Harper's Magazine.

Illustration for story 'The Anatomy of Panic, A personal history of anxiety' by Michael W. Clune. To see more of her work visit: https://lnkd.in/e7jZdEbF

#illustration#editorial illustration#conceptual illustration#illustrationzone#illustrator#conceptualart#conceptual art#fear#ballpenart#ballpendrawing

0 notes

Text

Candide @ Menier Chocolate Factory 2013 (#27)

Title: Candide

Venue: Menier Chocolate Factory

Year: 2013

Condition: Creasing to edges

Author: Music by Leonard Bernstein Book Adapted from Voltaire by Hugh Wheeler Lyrics by Richard Wilbur Additional Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim John Latouche Lillian Hellman Dorothy Parker and Leonard Bernstein

Director: Matthew White

Choreographer: Adam Cooper

Cast: James Dreyfus, Fra Fee, Cassidy Janson, David Thaxton, Scarlett Strallen, Helen Walsh, Michael Cahill, Ben Lewis, Frankie Jenna, Jeremy Batt, Jackie Clune, Carly Anderson, Christopher Jacobsen, Matt Wilman, Rachel Spurrell

FIND ON EBAY HERE

0 notes

Photo

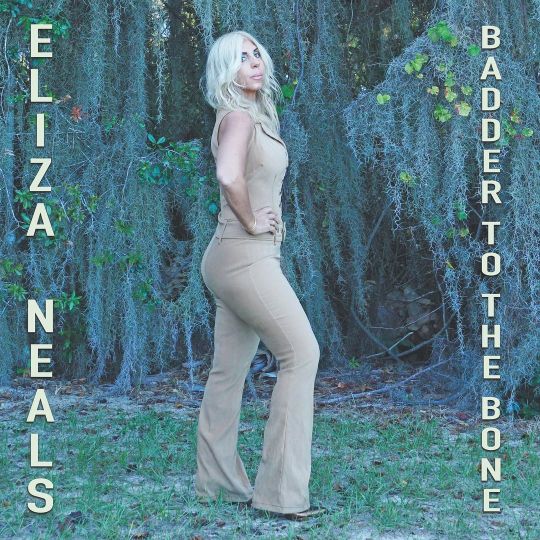

"Standing tall in sandy grass and Spanish Moss you will find Eliza Neals with her fresh modern Blues-rock album “Badder to the Bone,” OUT💫April 23rd,💫2022. A whole two years after releasing “Black Crow Moan” her critically acclaimed, ‘psychic’ blues album predicting isolation of a global shut-down. Eliza Neals returns with a riptide of Blues-rock on “#BaddertotheBone.” Texas hot sauce guitarist extraordinaire Lance Lopez (SuperSonic Blues Machine, Lucky Peterson) with Detroit Rock-N-Roll Hall of Famer Billy “JC” Davis (Hank Ballard & The Midnighters, Jimi Hendrix) and co-producer Michael Puwal (ICP, Kenny Wayne Shepard) present a searing guitar. Drum skins trounced by Detroit natives best Skeeto Valdez (King Konga, Johnnie Bassett) and Jeffery ‘Shakey’ Fowlkes (Too Slim) along with Nashville’s Tim Grogan (Desert Rose Band) plus Brian Clune, leaves the sand shifted. Flexing the muscle on Bass is Detroit’s own Paul Randolph (Alice Cooper, Mudpuppy), motor-city studio man Jason Kott (Robert Randolph) and Michael Puwal. Ivory bone strikes hammer on Hammond B3, grand piano and Wurlitzer by Detroit Rock City’s finest Peter Keys (Lynyrd Skynyrd) and John Galvin (Molly Hatchet) with Eliza Neals laying down the skeleton. Michigan soul singer Kymberli Wright’s (Straight Ahead), back up vocal is supreme. Synthesizing a body from the pandemonium wreckage key by key, bone by bone, up from below, kneeling now standing, Eliza Neals proves she’s a powerful voice in modern Blues-rock. Touring and constant songwriting in American roots, blues music puts all systems go on “Badder to the Bone.” Executive Produced for E-H Records LLC info(at)e-hrecords.com for #Radio & #Press 🟢 #PreOrder #linkinbio #NewMusicAlert #MusicMonday #AmericanRoots #BluesMusic #Musician #FemaleProducer #Songwriter #Arranger #ClassicRock #DetroitRock #PowerBlues #RockBlues #SoulBlues #ContemporaryBlues #NewBlues #IndieBlues #ModernBlues #bluesballad #NewRelease #Preordernow #Bluesrock #musiclovers #lightninginabottle #thevelvetwhip #ElizaNeals 🔥 (at Brill Building) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cb7oeN9OUbk/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#baddertothebone#radio#press#preorder#linkinbio#newmusicalert#musicmonday#americanroots#bluesmusic#musician#femaleproducer#songwriter#arranger#classicrock#detroitrock#powerblues#rockblues#soulblues#contemporaryblues#newblues#indieblues#modernblues#bluesballad#newrelease#preordernow#bluesrock#musiclovers#lightninginabottle#thevelvetwhip#elizaneals

0 notes

Text

"When you're an addict, if you can imagine life without drugs, it just seems to you like this boring, endless, pleasureless expanse. This desert. But freedom from that grind, freedom from that depression, that despair is like a high every day for me, to be honest. And then it just opens the door to all the ordinary pleasures of life."

-Michael Clune, author of White Out: The Secret Life of Heroin, in an interview on sobriety

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The reigning queen of American letters and MSNBC-brained lib extraordinaire humanistically reproves one of the most notable of American letters’ ultra-right-wing upstarts, a hyper-racist celebrant of his reactionary namesake and the anti-humanist reducto-materialism for which he tentacularly stood. “Quite a meeting of the minds here,” someone quipped in the quote Tweets.

There’s less ideological distance between them than appears from their Twitter feeds, hers almost comically aligned with official ideology, his just as strenuous a performance of almost psychotic distance from it or any other liberal norm. But as I’ve observed already, she encrypts in her fiction a worldview at odds with her political rhetoric, at least based on the handful of works I’ve read out of her massive oeuvre, and at least as one possible or plausible view of life. And she admires the first Lovecraft, the real Lovecraft, having written a long introduction to one of the reprint collections. As for who is the superior author between JCO and 0HP, there’s no question. He’s a one-note Nancy and a shallow pasticheur, whereas she at her best—for example, in We Were the Mulvaneys—can channel the very wind and rain.

Who’s right in the quarrel above? They may both be right; there may be no contradiction between their two prophecies. Some will be replaced by the machine—they were, she says elsewhere in the feed, machines already (not a terribly liberal sentiment, by the way)—and some will thrive in a more restricted artisanal market. But her reference to “home cooking” is the real clue in the labyrinth.

I’m seeing too much despair over the AI question from writers and artists. It’s too late to complain about this; the time to complain was when Hegel subjected art to a theory of historical progress which guaranteed everybody’s eventual obsolescence. (I use “Hegel” as a convenient shorthand for a broad shift toward historicism in western aesthetics; one could use other names, from Vico to Darwin, and one could read Hegel in other ways.) The robots have come to finish that job, not to start anything new. I suggest another way to look at the question. “I side with humanity” may fail as rhetoric—too sentimental, too science fictional. So I put the assertion more selfishly: I side with myself.

We will be enjoined to surrender to the robots for both left-wing and right-wing reasons: as a xenophilic openness to the technological Other, as a democratic extension of art-making to everyone, and as a bow to the market’s demand for maximal efficiency and low labor costs in all things. All sound Hegelian dissolutions of art into the social matrix in its ethical, political, and economic guises. So why go on making art? Well, why did we start in the first place? Why do I cook when I could just order take-out?

I leave you with this hint, from an essay I first shared to this very website about a decade ago. It’s not obviously related to the matter in hand, but its main claim—that the artist’s own satisfaction and self-transfiguration in the artistic process is an intrinsic good needing no worldly defense—settles the whole question:

Bernhard agrees with critics like Bourdieu in denouncing art’s covert parasitism on the networks of social status. But he disagrees about what to do. Bourdieu wants to jettison the ideal of the aesthetic as disinterested attention to form. This might annihilate some forms of snobbery. But it is hard to imagine that settling accounts with Kant will do much to change the social world’s basic nature as a hierarchy founded on fear and pain. Bernhard, with a deep understanding of how art has been infected by the social relations described by postmodern critics, reacts more rationally. Don’t get rid of art; get rid of social relations.

The satisfaction of the highest art for Bernhard thus defines a human space both replete with value and outside society. In this it does not look so different from the Kantian ideal of aesthetic experience. But there is a crucial difference. For Bernhard, accepting the truth of the postmodern critique means accepting that every relation between an artwork and an audience becomes enmeshed in status relations. Bernhard faces the consequences squarely. The “real satisfaction” of art can never be achieved by the audience of a work, but only and solely by its creator.

—Michael W. Clune, “Bernhard’s Way”

#joyce carol oates#zero hp lovecraft#michael w. clune#thomas bernhard#ai#literature#literary criticism

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

One of Our Aircraft Is Missing | Michael Powell / Emeric Pressburger | 1942

Peter Ustinov, Alec Clunes, et al.

#Peter Ustinov#Alec Clunes#Michael Powell#Emeric Pressburger#Powell and Pressburger#One of Our Aircraft Is Missing#1942

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Some soft thirst, alright. Who do you think would be nice to have just lay on top of you? While my first thought in any scenario is always Willy, I'd have to think players like Mo, Hanifin, Drai, or Lowry would all make excellent candidates.

while my lungs are shit™ and I’d definitely die if a fully grown human laid on top of me (come to think of it even a toddler could kill me in that way) i’d really like several fully grown humans to lay on top of me... just not at the same time

the ones you picked are peak blanket material but I’d also add:

- Auston Matthews (he’s big)

- Andre Burakovsky (he’s cuddly)

- Brock McGinn (not a personal blanket choice but just imagine laying down and feeling big cock Brock’s cock while he snuggles you)

- Colton Parayko (he’s BIG™)

- Casey Mittelstadt (he’s soft)

- Cale Makar (it just seems like a thing he’d do)

- Freddie Andersen (also a big)

- Jamie Benn (about as complex as a blanket, perfect for the job)

- Mitch Marner (very cuddly)

- Michael Latta (solid)

- Nicklas Backstrom (murder blanket)

- Rich Clune (is Rich Clune)

- Sebastian Aho (also looks soft)

- Tyson Barrie (is a Tyson)

- Tyson Jost (is a Tyson)

- Zach Hyman (buff arms hold me please)

#william nylander#morgan rielly#noah hanifin#leon draisaitl#adam lowry#auston matthews#andre burakovsky#brock mcginn#colton parayko#casey mittelstadt#cale makar#freddie andersen#jamie benn#mitch marner#michael latta#nicklas backstrom#rich clune#sebastian aho#tyson barrie#tyson jost#zach hyman#kink list

141 notes

·

View notes