#mansion he has three jobs he plays piano hes a family man hes bad at giving advice hes charming hes mirrors hes surprised when people genuin

Text

im like. i dont understand my favorite character. but also no one understands him like me.

#im working on it okay. ive got a multi page document for working it out.#but also anyone who thinks hes like a normal guy has got another think coming. hes just some guy but hes not normal#also anyone who thinks miss p is like.. soft uwu shy book girl. she kills people. she drinks wine with rocks in it#hes a mischief maker hes a friendly guy hes arrogant hes loud hes haunted literally and metaphorically hes over six feet tall he lives in a#mansion he has three jobs he plays piano hes a family man hes bad at giving advice hes charming hes mirrors hes surprised when people genuin#ely like him hes the class clown (but he wasnt he was a withdrawn and easily angered child) hes the life of the party he is the party he lik#es being a fun guy he gets kind of weepy but uh oh look out hes back to happy he doesnt want to bring the mood down

1 note

·

View note

Text

But You Can Never Leave [Chapter 5: Don’t Even Think About It]

Hi y’all! I’m so sorry I’ve been gone for so long...finals and job hunting got the best of me. I will be updating more frequently going forward. As always, thank you so much for reading!! 💜😘

Series summary: You are an overwhelmed and disenchanted nurse in Boston, Massachusetts. Queen is an eccentric British rock band you’ve never heard of. But once your fates intertwine in the summer of 1974, none of your lives will ever be the same...

This series is a work of fiction, and is (very) loosely inspired by real people and events. Absolutely no offense is meant to actual Queen or their families.

Song inspiration: Hotel California by The Eagles.

Chapter warnings: Language, very very very little sexual content.

Chapter list (and all my writing) available HERE

Taglist: @queen-turtle-boiii @loveandbeloved29 @killer-queen-xo @maggieroseevans @imnotvibingveryguccimrstark @im-an-adult-ish @queenlover05 @someforeigntragedy @imtheinvisiblequeen @joemazzmatazz @seven-seas-of-ham-on-rhye @namelesslosers @inthegardensofourminds @deacyblues @youngpastafanmug @sleepretreat @hardyshoe @bramblesforbreakfast @sevenseasofcats @tensecondvacation @bookandband @queen-crue

Please yell at me if I forget to tag you! :)

You’re in the crowd at The Rainbow, although you aren’t sure why; this has already happened.

Freddie is skulking across the fog-draped stage as he belts out the chorus of In The Lap Of The Gods...Revisited, all glistening tan skin and teased hair, a pillar of nimble black leather; John is only a silhouette in the mist. Brian looks like something that’s crawled out of a cocoon: leggy and insect-like, the sleeves of his flowing white blouse like a pair of wings. And Roger...Roger’s in the back, of course—“the hardworking one in the back,” he always says—with a glittery black kimono-like shrug hanging loosely off his bare shoulders. He’s drumming feverishly, sprays of Heineken flying off his floor tom, his forehead and blond hair dripping.

“Whoa, whoa, la la la, whoa...

I can see what you want me to be,

But I'm no fool,

It's in the lap of the gods...”

Somehow, as the fog clears, Roger’s eyes find you in the crowd. He grins in that effervescent, blameless way that he does. And now you know for sure that this is a dream; because there’s no chance Roger could see that far without his glasses.

There’s a banging noise coming from somewhere, but it’s muted, distant, splintered like an echo.

Dream Roger is fading away, dissolving as the lights shade to black on the stage. He disappears, and then Freddie does too, and then Brian, and finally John. The crowd you’re standing in is a sea of churning, indistinguishable faces.

The banging grows louder, closer. You can hear a new voice now.

You swim up from unconsciousness and punch into daylight. You’re laying on your back in bed in a small, rustic hotel room; it takes you a second to remember what the world looks like now. It’s not November at the Rainbow Theater. It’s December 11th, and you’re in Rome.

You sit up in bed and turn towards the door. Whoever is out there is knocking so forcefully that the distressed wood rattles on its hinges.

“Hey, Dorothea Dix, wake up!” Freddie is shouting through the door.

You rub your eyes as your feet touch the cool teak floor. The band flew into Rome late last night, and has one full day to burn before their concert on the 12th. You’d pitched the idea of visiting a few museums, the Colosseum, the Pantheon, the Roman Forum, St. Peter's Basilica, maybe even the Baths of Caracalla or the Temple of Venus and Roma; but it had been difficult to get anyone to commit at 2 a.m. when you were all exhausted and dragging luggage into the modest, quite geriatric hotel. Queen may finally have a Top 20 album in the U.S., but the streets aren’t paved with gold just yet.

“Darling, need I remind you that this was all your idea, you simply must wake up this instant—!”

You swing the door open. Freddie is standing in the hallway in a vivid yellow-and-black jacket and white jeans, tall boots, dark hair huge and curly, folded aviator sunglasses peeking out of his pocket.

“Get ready, bitch,” he says, grinning, then slips the sunglass over his dusky eyes. “All those gorgeous marble blokes with their cocks hanging out aren’t going to ogle themselves.”

~~~~~~~~~~

You start with the ruins, then end up at the National Roman Museum after lunch. Brian and Chrissie meander through the halls of cracked marble goddesses and heroes and piecemeal fractions of bodies, their hands intertwined; Chrissie took a few days off work to meet the band in Rome, and she’s glowing with the thrill of being reunited with Bri. Freddie is contemplating the displays, tapping his chin thoughtfully and chatting as John nods along and sketches in his notebook. There’s a photographer scurrying around snapping photos of the band for some magazine, to the vexation of the museum employees. They scowl from the corners of the rooms, their suits pristine and arms crossed, muttering to each other in Italian.

Roger leaps in front of a hulking statue of Perseus and mimics the pose. “What do you think?” he asks you, wielding an invisible spear. “Am I courageous? Divine? A mirror image?”

“You’ll have to work on the hair. And gain like a hundred pounds.”

He wrinkles his nose. “Pounds?!”

“Whoops. Kilos. A lot of kilos. But I think I like you as you are. Can I see your hands?”

Roger falls out of his pose, smiling. “Yes ma’am.” He presents his palms for inspection. The first weeks had been hell for him as his hands were worked into touring shape, repeatedly blistered and worn raw, iced and treated and bandaged by you each night only to be pummeled all over again the next day. Of course, Roger hadn’t described it that way; he shrugged at the blood and swollen knuckles, his eyes already alight with the promise of future shows. That’s just a casualty of fame, love, he’d told you. I’d take it all again and more. The last of his blisters have healed now into discolored callouses, rough whirlpools of memories from cities like Glasgow and Bristol and Helsinki and Munich. “I can get more pounds too, you know. I’ll be swimming in them. I’m gonna buy you a mansion when we get home.”

“Not so fast, blondie.” You graze your thumbs over his rugged palms and release him. Aside from your annoyingly incessant concern for Roger, your job hasn’t proved to be too taxing: there have been sprains, minor lacerations, severe hangovers, some alcohol poisoning, and one case of syphilis that you identified and sent the unfortunate man to a doctor for, all of which afflicted the roadies rather than the band.

“How’s Jo doing?” Chrissie calls over from where she and Brian are scrutinizing a sculpture of Apollo. She tosses Roger a smirk.

“Fine,” he replies briskly. “It was amicable. She understood. Nothing personal, just with the tour and everything we knew it wasn’t going to work out. Bad timing, that’s all.”

“Hm. That’s not exactly how she described it.”

Roger sighs, irritated. “Well, Chris, I really can’t control what she chooses to tell you, can I?”

“Shhhh. Play nice, love,” Brian coos, massaging Chrissie’s shoulders.

Roger pops a cigarette between his lips and moves to light it. A museum employee rushes over, waving his arms frantically. “Per favore, signore, no smoking near the exhibits—!”

“Oh, right, right. Sorry.” Roger tucks the cigarette away, then turns back to you. “Okay, no mansion then. What’s your fancy? Diamonds and gold? Tigers on leashes?”

“A harem of sensual Italian men?” Freddie suggests. Chrissie bursts out laughing.

“I hope not,” Roger says.

“You know what I really want?” you say, eyeing busts of Hadrian and Nero.

“What?” Chrissie asks.

“A camera. A really good one. To document all of this, our adventures. I mean, I know we have...” You wave towards the magazine photographer, who’s mostly snapping shots of Freddie and Roger. “But it would be nice to have my own photos. Carry them around in my wallet, force strangers to look at them, cover my refrigerator with them, all that sentimental stuff. So the minute you kids start making real money, I’d like a nice Canon. Or a Nikon. Or whatever the best camera is.”

“The Canon F-1 is quite good,” the photographer offers.

“Perfect! Clearly, I know nothing about cameras. And will need a hefty instruction manual. But I’m still excited.”

Roger winks. “I believe in you.”

As you all wander into the next room, Freddie spies a grand piano and sprints to it. He slides onto the bench and begins testing the keys. A distraught museum employee appears instantly.

“Signore, please, this is for the museum staff only, please signore!”

“Oh relax, darling, I won’t break it.” He begins experimenting with some light, jazzish melody.

“I love Rome,” you decide as you stroll past the Aphrodite of Menophantos. “Are you sure we can’t stay here forever?”

John frowns as he shades in whatever he’s drawing in his notebook. “It’s too bad we couldn’t make it to Florence.”

Freddie rolls his eyes from the piano. “Deaky, darling, this Dante’s Inferno obsession has got to go. It’s positively morbid.”

“He ends up in paradise,” John protests wryly.

Freddie snorts. “Yes, well, Florence is a three hour drive each way. Next time perhaps. Once we’ve all got private jets and Nurse Nightingale over there has her posh camera.”

“And we’ve acquired trophy wives to pose with us,” Brian jokes. Chrissie squeals and shoves him good-naturedly.

“We could go to the beach,” John proposes.

“A seaside rendezvous?” you say playfully.

Freddie hums and nods as his fingers fly over black and white keys.

“Signore...” the museum employee begs. The photographer circles Freddie and the piano, snapping picture after picture.

“The beach?!” Roger whines. “It’s too cold for that! We can’t swim, we can’t sunbathe practically naked, what’s the point? And we’re checking out that club tonight. The one by the hotel, what’s it called, Fred? El Fuocolio?”

“Il Fuoco,” Freddie corrects, amused.

“Ah. Forgive me for not keeping up with my Italian.”

“We don’t all listen to opera, you know,” you tease Freddie. He peers over at you thoughtfully, then continues playing. “I’ll go to the beach with you, John.”

He almost drops his notebook and pencil. “Will you?”

“Of course. I’ll have fewer opportunities in my life to see the Italian seaside than get tipsy and evade dodgy men at some bar, most likely. Although I will miss seeing your dancing.”

“Aww!” Now Roger is dejected, his huge blue eyes pleading. “You have to come with us.”

“Next time,” you promise him.

“This time.”

“Next time.”

“Fine.” He points at John. “Don’t let her get eaten by a shark or run off with some Italian playboy.”

John grins. “I’ll do my best.”

Two burly security guards arrive and begin shouting at Freddie in Italian. “Oh fine, fine!” he snaps as he stands and abandons the piano. The museum employee beams triumphantly.

“Fred, I think we’ve tormented them enough,” Brian says.

“Bri, can we go to the beach too?” Chrissie asks. “Please?”

“It’ll be chilly.”

“I have a jacket. And I can borrow yours if necessary.”

Brian chuckles. “Okay. We can go. Ostia’s the closest one, I suppose.”

“You’ll love it,” you tell him. “It’ll be like time travelling. You get to stand on the same shore that the ancient Romans did, bury your feet in the same sand, watch the same sunset. That should appeal to an astrophysicist such as yourself.”

“How poetic,” John muses.

Roger comes to you, shrugs off his black leather jacket, drapes it over your violet sweater.

“Roger, don’t—”

“I’ll miss you,” he interrupts, smiling, then presses his lips fleetingly to your forehead.

~~~~~~~~~~

The four of you take a crowded, decidedly unglamorous bus to Ostia and walk the beaches under the fading afternoon sun. It is chilly by the crashing water, and the wind whips across your cheeks forcefully enough to sting; but none of that stops you. Brian and John collect seashells, and Brian retreads all the details of the tour—all the things he wishes he could do over, all the things he wants to change going forward—as John listens, smoking and nodding when appropriate. You and Chrissie kneel in the cool sand and shape castles with your hands, giggle about how messy and lopsided they are, scribble notes in the soft sifting remnants of stone and quartz: Chrissie loves Bri, Buy Sheer Heart Attack today, Queen was here. And you’re thinking about Roger more than you should be, and Chrissie knows it; but she’s not going to say anything about that now.

When the boys come back, Bri sits in the sand next to Chrissie and begins to decorate her castle with the shells he found: scallops and clams and tulip shells and oysters and tiny lightning whelks. She claps and hugs him, leaps into his lap, pulls him in for a kiss.

“This is terribly unfair,” you say, staring morosely at your now even less impressive sandcastle.

John appears beside you and offers a massive pink conch filled with very small, pristine, glossy shells. You gasp and clasp a palm over your heart.

“Really?!”

“Yeah,” he says, puzzled. “Who do you think I picked them for?”

“You’re the best. The absolute best. A treasure. I owe you my life. Wait...” You pick up a thin shard of driftwood and write into the side of your sandcastle: John Deacon, and then a heart encircling it. “You are officially lord of the sandcastle.”

“A prestigious position, surely,” he says, smiling, then passes you the conch. “Go on.”

As you place the shells, he finds a dried bit of seaweed and impales it on the piece of driftwood, then plants the makeshift flag on the tallest tower of the castle.

Brian glances over and shakes his head, his mess of curls shivering. “Chris, love, I fear we’ve been outdone.” Then he nods to the words you and Chrissie carved with your fingertips. “Leaving letters in the sand?”

“Promotional material,” you quip; but you can tell the wheels in Brian’s magnificent mind are whirling.

As the sun sets over the Mediterranean Sea, golden speckles of light floating disembodied on the waves, the four of you get gelato and browse through bookstores and wander down cobblestone streets. And on the bus ride back to the hotel, Brian points out constellations as you hold the conch shell in your lap and doze against John’s shoulder.

~~~~~~~~~~

Brian and Chrissie depart to get dinner when you arrive back at the hotel, taking the rare opportunity for a date night. You try to think of a more romantic destination than Rome. Paris? New York? Venice? Probably none of those. You push the images that flood your thoughts away: candlelit meals with violins serenading in the background, the warm cascading glow of streetlights, tossing coins into fountains older than either London or Boston, gazing over the table and into the ensnaring oceanic eyes of the person who won’t be there. Roger.

“Do you think Roger and Fred are back yet?” you ask John in the lobby. He’s still got his notebook in his jacket pocket, but he won’t let you see it.

“I doubt it, but let’s find out.”

You ride the elevator to the band’s floor, still clutching the conch shell, as John fields ideas for dinner.

“Roger’s going to want pizza and beer, but we might be able to get Freddie to go for something more swanky. Actually, he’ll probably order dessert first. There’s a restaurant down the street that I heard has phenomenal tiramisu and lasagna.”

“Oh god. I would kill for a good lasagna.”

“No need for all that,” John says. “We don’t have enough cash for your bail.”

“If they serve lasagna in prison, you can leave me here.”

“But then who would patch up our debaucherous roadies?!”

You laugh as the elevator lurches to a halt and the doors open. “Just call me up in prison and I can talk you through it—”

You step out and turn down the hallway; then all the air vanishes from your lungs. Roger’s fumbling with his key as he tries to get into his room...and pressed between him and the door is a raven-haired, modelesque woman in a short red dress. His eyes are closed, her tongue darting between his lips, his free hand skating up her bare thigh and beneath her dress. And suddenly you’re being dragged back into the elevator, John’s arms locked around your waist. He hits the button for the lobby then reaches for you uncertainly.

“Are you okay—?”

“Yeah, I’m fine, I’m totally fine, I’m...” But for some reason, your throat is burning and your eyes are blurring with tears. You try to blink them away and they drop down your cheeks like rain.

“You’re not,” he realizes softly.

“Goddammit,” you choke out, sobbing.

“Hey, don’t do that,” John pleads. “Please don’t do that, please don’t cry—”

“Oh god, I’m so sorry, this is so stupid...” You fan your face and try to wrangle your breathing. The way he was touching her...I can’t forget the way he was touching her. “I am so stupid.”

“You’re not,” John flares. And when he opens his arms you rush into them, burying your face in his jacket as he pulls you closer, drowning you in his warmth. “You’re not stupid,” he says, quietly but severely. “You’re wicked smart and wonderful and perfect, so you’re not allowed to say anything to the contrary. Alright?”

“Okay,” you whisper. And it occurs to you—as your breathing slows, as your tears subside—how incomparably comfortable this feels, homey even.

John clears his throat. “Hey, not to break this up or anything, but you’re sort of stabbing me with the conch shell.”

Incredibly, you laugh as you back away, swiping at your eyes. “Sorry.”

The elevator doors open, and John leads you out into the lobby. “Here’s what’s going to happen,” he says. “We’re going to go to that restaurant on the corner and I’m going to order a lasagna—”

“John, I don’t think I can eat anything.”

“Doesn’t matter. Did I say you were going to be forced to eat it at gunpoint? No I did not. I’m going to order a lasagna, and if you want some awesome, and if you don’t we’ll just sit and talk. And you can nibble table bread or drink so much wine you forget today ever happened, whatever you want. You make the rules. But we’re going, and I’m ordering lasagna.”

“Okay,” you reply, sniffling, smiling up at him gratefully.

The restaurant is teeming with tourists, and you end up seated at a tiny table near the back with very dim lighting and a roaring fireplace. It’s deliciously hot, burning away your misery; or, at least, making it feel as if it might belong to someone else, as if maybe you heard about it from a friend or in a song, maybe even dreamed it. You take Roger’s leather jacket off and hang it on the back of your chair. When the waiter arrives, John orders for you.

“One lasagna, the biggest one you have, and extra table bread, and uh...” He skims the menu. “Two red wines and a Coke. And a sparkling water. So the lady has a selection.”

“Si, signore. Grazie.”

When the waiter leaves, John lifts off his jacket too, then unbuttons his shirt to his navel. The sweltering glow of the firelight dances across his pale skin in a way that is mysteriously distracting. “Well, it definitely doesn’t feel like December in here.”

“I’m sorry, maybe they could move us—”

“No, that’s alright, I know you like it. And one should be sweating in Southern Italy, don’t you think?” He tears off a hunk of bread when it arrives and plates it for you. The conch shell lays on the table by the salt and pepper shakers, to the visible confusion of the waiter.

“Thank you. For everything, John. Really.”

He gazes at you with those blue-grey eyes that can look like either clouds or steel depending on the occasion. Tonight they are misty, like the froth over waves, impossibly soft. “It doesn’t mean anything,” he says gently. “I don’t know if that helps at all, but I think it should. It doesn’t mean anything to someone like Roger, what you saw tonight.”

You sigh. “I guess it doesn’t. And I’m sorry, I know it’s ridiculous, I know that, and I’m just so frustrated and...and...I get it, I get that I have no right to care about anything Roger does, which is why I feel like such an idiot for reacting this way, but I just...I just...I’m just so...so fucking torn up about it and I’m sick of being surrounded by it all the time and I’m...I’m so...I’m...look, I’m sorry, can you button your shirt or something? That’s very distracting.”

“Oh, it’s distracting, is it?” John asks, grinning.

“Don’t you dare—”

He undoes several more buttons. “How about now, are you sufficiently distracted?”

“John, no!” you wail, laughing.

“I wouldn’t want to do anything to distract you from your tortured inner monologue...” He removes his shirt entirely and tosses it to the floor. “How are you now?”

“Very distracted,” you wheeze.

“Excellent.” He smiles, resting his face in his hands, the firelight flickering over his bare chest and shoulders, reflections of flames in his eyes. “See, you don’t look so sad now.”

“No, I guess I don’t.” You bite into your hunk of bread. But still, the way he was touching her...

John sips red wine and smirks teasingly. “You know...if you ever get tired of the celibate lifestyle...I’m always game.”

You laugh, shaking your head, and open the Coke bottle. “That’s very much appreciated. But I don’t just want sex.”

“I know,” he replies, solemnly now. “You want him.”

“That’s pretty pathetic, isn’t it?”

“I don’t think you’re pathetic at all.” That seems like it must be a lie, but John sounds genuine.

“You’re my best friend, you know,” you tell him. “I don’t know what I would do without you.”

“Certainly not get treated to authentic Italian lasagna.”

You chuckle. “I’m sure that’s the least of your talents. Veronica is a very lucky woman.”

John nods, staring down at the table now, pushing crumbs around with the back of his hand. “If you say so.”

And, in the end, you managed to eat your half of the lasagna after all.

~~~~~~~~~~

When you get back to your hotel room, it’s very late in Italy...which means it’s only early evening in Boston. You pick up the phone and resolve to use the last of your miniscule weekly allowance for a long distance call.

Your mom answers on the third ring. “Hello?”

“Guess where I am right now.”

“Hopefully on a date with that nice Roger boy.”

“Oh my god, Mom.”

She titters pleasantly. “Tell me, dear. Germany? No, no. Spain.”

“Rome.”

“Oh!” she sighs, steeped in nostalgia. “Daddy and I went there on our honeymoon! Ages ago, of course. But it was wonderful, otherworldly. Like getting lost in a fairytale. How do you like it?”

“I love it,” you murmur. “Mom, can I ask you something?”

“Always, dear.”

You twirl the phone cord around your fingers anxiously. “How did you know that Dad was the one?”

“Hm.” She pauses; and you can envision the way she takes a step back and glances up at the ceiling whenever she’s thinking something over. Oh, maybe I do still miss parts of Boston. “Well...you know Daddy wasn’t single when we met. And neither was I.”

“Yeah, I think I remember that part of the story.”

“I’m not sure if I can explain it, dear. Truly. I...” She drifts off, pondering it. Finally, she says: “I’d had plenty of other boyfriends. I’d been interested in other people. And people are all so different, they all have something unique to offer to your life, whether good or evil. But when I met your father...I just felt like I couldn’t live without him. Suddenly nothing else seemed possible if he wasn’t in the picture. Like if he wasn’t there I’d spend the rest of my life missing him. Does that answer your question?”

“It does, yeah.” You close your eyes and feel the dark Mediterranean night air breeze in through the open window. The conch shell has found a temporary home on top of the antique dresser. “I love you, Mom.”

“Aww, I love you too, honey. And you’ll make the right decision, whatever that is.”

You look out into the constellations that Brian introduced to you earlier, Aries and Fornax and Perseus. “I hope so.”

#queen#queen fic#roger taylor fic#but you can never leave fic#but you can never leave series#but you can never leave#queen fanfic#john deacon fic#roger taylor x reader#john deacon x reader

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

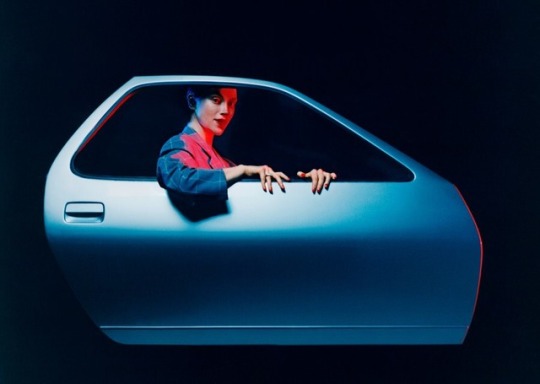

Switching Lanes With St. Vincent

By Molly Young

January 22, 2019

Jacket (men’s), $4,900, pants (men’s), $2,300, by Dior / Men shoes, by Christian Louboutin / Rings (throughout) by Cartier

On a cold recent night in Brooklyn, St. Vincent appeared onstage in a Saint Laurent smoking jacket to much clapping and hooting, gave the crowd a deadpan look, and said, “Without being reductive, I'd like to say that we haven't actually done anything yet.” Pause. “So let's do something.”

She launched into a cover of Lou Reed's “Perfect Day”: an arty torch-song version that made you really wonder whom she was thinking about when she sang it. This was the elusive chanteuse version of St. Vincent, at least 80 percent leg, with slicked-back hair and pale, pale skin. She belted, sipped from a tumbler of tequila (“Oh, Christ on a cracker, that's strong”), executed little feints and pounces, flung the mic cord away from herself like a filthy sock, and spat on the stage a bunch of times. Nine parts Judy Garland, one part GG Allin.

If the Garland-Allin combination suggests that St. Vincent is an acquired taste, she's one that has been acquired by a wide range of fans. The crowd in Brooklyn included young women with Haircuts in pastel fur and guys with beards of widely varying intentionality. There was a woman of at least 90 years and a Hasidic guy in a tall hat, which was too bad for whoever sat behind him. There were models, full nuclear families, and even a solitary frat bro. St. Vincent brings people together.

If you chart the career of Annie Clark, which is St. Vincent's civilian name, you will see what start-up founders and venture capitalists call “hockey-stick growth.” That is, a line that moves steadily in a northeast direction until it hits an “inflection point” and shoots steeply upward. It's called hockey-stick growth because…it looks like a hockey stick.

Dress, by Balmain

The toe of the stick starts with Marry Me, Clark's debut solo album, which came out a decade ago and established a few things that would become essential St. Vincent traits: her ability to play a zillion instruments (she's credited on the album with everything from dulcimer to vibraphone), her highbrow streak (Shakespeare citations), her goofy streak (“Marry me!” is an Arrested Development bit), and her oceanic library of musical references (Kate Bush, Steve Reich, uh…D'Angelo!). The blade of the stick is her next four albums, one of them a collaboration with David Byrne, all of them confirming her presence as an enigma of indie pop and a guitar genius. The stick of the stick took a non-musical detour in 2016, when Clark was photographed canoodling with (now ex-) girlfriend Cara Delevingne at Taylor Swift's mansion, followed a few months later by pictures of Clark holding hands with Kristen Stewart. That brought her to the realm of mainstream paparazzi-pictures-in-the-Daily-Mail celebrity. Finally, the top of the stick is Masseduction, the 2017 album she co-produced with Jack Antonoff, which revealed St. Vincent to be not only experimental and beguiling but capable of turning out incorrigible bangers.

Masseduction made the case that Clark could be as much a pop star as someone like Sia or Nicki Minaj—a performer whose idiosyncrasies didn't have to be tamped down for mainstream success but could actually be amplified. The artist Bruce Nauman once said he made work that was like “going up the stairs in the dark and either having an extra stair that you didn't expect or not having one that you thought was going to be there.” The idea applies to Masseduction: Into the familiar form of a pop song Clark introduces surprising missteps, unexpected additions and subtractions. The album reached No. 10 on the Billboard 200. The David Bowie comparisons got louder.

This past fall, she released MassEducation (not quite the same title; note the addition of the letter a), which turned a dozen of the tracks into stripped-down piano songs. Although technically off duty after being on tour for nearly all of 2018, Clark has been performing the reduced songs here and there in small venues with her collaborator, the composer and pianist Thomas Bartlett. Whereas the Masseduction tour involved a lot of latex, neon, choreographed sex-robot dance moves, and LED screens, these recent shows have been comparatively austere. When she performed in Brooklyn, the stage was empty, aside from a piano and a side table. There were blue lights, a little piped-in fog for atmosphere, and that was it. It looked like an early-'90s magazine ad for premium liquor: art-directed, yes, but not to the degree that it Pinterested itself.

Coat, (men’s) $8,475, by Versace / Shoes, by Christian Louboutin / Tights, by Wolford

The performance was similarly informal. Midway through one song, Clark forgot the lyrics and halted. “It takes a different energy to be performing [than] to sit in your sweatpants watching Babylon Berlin,” she said. “Wherever I am, I completely forget the past, and I'm like. ‘This is now.’ And sometimes this means forgetting song lyrics. So, if you will…tell me what the second fucking verse is.”

Clark has only a decade in the public eye behind her, but she's accomplished a good amount of shape-shifting. An openness to the full range of human expression, in fact, is kind of a requirement for being a St. Vincent fan. This is a person who has appeared in the front row at Chanel and also a person who played a gig dressed as a toilet, a person profiled in Vogue and on the cover of Guitar World.

The day before her Brooklyn show, I sat with Clark to find out what it's like to be utterly unstructured, time-wise, after a long stretch of knowing a year in advance that she had to be in, like, Denmark on July 4 and couldn't make plans with friends.

“I've been off tour now for three weeks,” she said. “When I say ‘off,’ I mean I didn't have to travel.”

This doesn't mean she hasn't traveled—she went to L.A. to get in the studio with Sleater-Kinney and also hopped down to Texas, where she grew up—just that she hasn't been contractually obligated to travel. What else did she do on her mini-vacation?

“I had the best weekend last weekend. I woke up and did hot Pilates, and then I got a bunch of new modular synths, and I set 'em up, and I spent ten hours with modular synths. Plugging things in. What happens when I do this? I'm unburdened by a full understanding of what's going on, so I'm very willing to experiment.”

Coat, by Boss

Jacket, and coat, by Boss / Necklace, by Cartier

Like a child?

“Exactly. Did you ever get those electronics kits as a kid for like 20 bucks from RadioShack? Where you connect this wire to that one and a light bulb turns on? It's very much like that.”

There's an element of chaos, she said, that makes synth noodling a neat way to stumble on melodies that she might not have consciously assembled. She played with the synths by herself all day. “I don't stop, necessarily,” she said, reflecting on what the idea of “vacation” means to someone for whom “job” and “things I love to do” happen to overlap more or less exactly. “I just get to do other things that are really fun. I'm in control of my time.” She had plans to see a show at the New Museum, read books, play music and see movies alone, always sitting on the aisle so she could make a quick escape if necessary. But she will probably keep working. St. Vincent doesn't have hobbies.

When it manifests in a person, this synergy between life and work is an almost physically perceptible quality, like having brown eyes or one leg or being beautiful. Like beauty, it's a result of luck, and a quality that can invoke total despair in people who aren't themselves allotted it. This isn't to say that Clark's career is a stroke of unearned fortune but that her skills and character and era and influences have collided into a perfect storm of realized talent. And to have talent and realize that talent and then be beloved by thousands for exactly the thing that is most special about you: Is there anything a person could possibly want more? Is this why Annie Clark glows? Or is it because she's super pale? Or was it because there was a sound coming through the window where we sat that sounded thrillingly familiar?

“Is Amy Sedaris running by?” Clark asked, her spine straightening. A man with a boom mic was visible on the sidewalk outside. Another guy in a baseball cap issued instructions to someone beyond the window. Someone said “Action!” and a figure in vampire makeup and a clown wig streaked across the sidewalk. Someone said “Cut!” and Clark zipped over for a look. It was, in fact, Amy Sedaris, her clown wig bobbing in the 44-degree breeze. The mic operator was gagging with laughter. It seemed like a good omen, this sighting, like the New York City version of Groundhog Day: If an Amy Sedaris streaks across your sight line in vampire makeup, spring will arrive early.

Blazer (men’s) $1,125, by Paul Smith

Another thing Clark does when off tour is absorb all the input that she misses when she's locked into performance mode. On a Monday afternoon, she met artist Lisa Yuskavage at an exhibition of her paintings at the David Zwirner gallery in Chelsea. Yuskavage was part of a mini-boom of figurative painting in the '90s, turning out portraits of Penthouse centerfolds and giant-jugged babes with Rembrandt-esque skill. It made sense that Clark wanted to meet her: Both women make art about the inner lives of female figures, both are sorcerers of technique, both are theatrical but introspective, both have incendiary style. The gallery was a white cube, skylit, with paintings around the perimeter. Yuskavage and Clark wandered through at a pace exclusive to walking tours of cultural spaces, which is to say a few steps every 10 to 15 seconds with pauses between for the proper amount of motionless appreciation.

The paintings were small, all about the size of a human head, and featured a lot of nipples, tufted pudenda, tan lines, majestic asses, and protruding tongues. “I like the idea of possessing something by painting it,” Yuskavage said. “That's the way I understand the world. Like a dog licking something.”

Clark looked at the works with the expression people make when they're meditating. She was wearing elfin boots, black pants, and a shirt with a print that I can only describe as “funky”—“funky” being an adjective that looks good on very few people, St. Vincent being one of them—and sipped from a cup of espresso furnished by a gallery minion. After she finished the drink, there was a moment when she looked blankly at the saucer, unsure what to do with it, and then stuck it in the breast pocket of her funky shirt for the rest of the tour.

A painting called Sweetpuss featured a bubble-butted blonde in beaded panties with nipples so upwardly erect they actually resembled little boners. Yuskavage based the underwear on a pair of real underwear that she'd constructed herself from colored balls and string. “I've got the beaded panties if you ever need 'em,” she said to Clark. “They might fit you. They're tiny.”

Earrings, by Erickson Beamon

“I'm picturing you going to the Garment District,” Clark said.

“There was a lot of going to the Garment District.”

As they completed their lap around the white cube, Clark interjected with questions—what year was this? were you considering getting into film? how long did these sittings take? what does “mise-en-scène” mean?—but mainly listened. And she is a good listener: an inquisitive head tilter, an encouraging nodder, a non-fidgeter, a maker of eye contact. She found analogues between painting and music. When Yuskavage mourned the death of lead white paint (due to its poisonous qualities, although, as the artist pointed out, “It's not that big a deal to not get lead poisoning; just don't eat the paint”), Clark compared it to recording's transition from tape to digital.

“Back in the day, if you wanted to hear something really reverberant”—she clapped; it reverberated—“you'd have to be in a room like this and record it, or make a reverb chamber,” Clark said. “Now we have digital plug-ins where you can say, ‘Oh, I want the acoustic resonance of the Sistine Chapel.’ Great. Somebody's gone and sampled that and created an algorithm that sounds like you're in the Sistine Chapel.”

Lately, she said, she's been way more into devices that betray their imperfections. That are slightly out of tune, or capable of messing up, or less forgiving of human intervention. “Air moving through a room,” Clark said. “That's what's interesting to me.”

They kept pacing. The paintings on the wall evolved. Conversation turned to what happens when you grow as an artist and people respond by flipping out.

“I always find it interesting when someone wants you to go back to ‘when you were good,’ ” Yuskavage said. “This is why we liked you.”

“I can't think of anybody where I go, ‘What's great about that artist is their consistency, ” Clark said. “Anything that stays the same for too long dies. It fails to capture people's imagination.”

Coat (mens), $1,150, by Acne Studios

They were identifying a problem with fans, of course, not with themselves. It was an implicit identification, because performers aren't permitted to critique their audiences, and it was definitely the artistic equivalent of a First World problem—an issue that arises only when you're so resplendent with talent that you not only nail something enough to attract adoration but nail it hard enough to get personally bored and move on—but it was still valid. They were talking about the kind of fan who clings to a specific tree when he or she could be roaming through a whole forest. In St. Vincent's case, a forest of prog-rock thickets and jazzy roots and orchestral brambles and mournful-ballad underlayers, all of it sprouting and molting under a prodigious pop canopy. They were talking about the strange phenomenon of people getting mad at you for surprising them. Even if the surprise is great.

Molly Young is a writer living in New York City. She wrote about Donatella Versace in the April 2018 issue of GQ.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2019 issue with the title "Switching Lanes With St. Vincent."

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

AL SMITH’S LOG CABIN

The lowest East Side, between the Brooklyn Bridge (completed in 1883) and the Manhattan Bridge (1909), was once a maze of narrow streets lined with row houses, corner saloons and groceries, warehouses, pickle factories, stables. The heart of it was an Irish and Italian working class neighborhood of large families who attended the venerable St. James church and school. It was not a slum or a ghetto, and the residents would have been highly insulted to hear it called that. With the construction of the bridges, followed by high-rises and the FDR Drive in the twentieth century, many of the old streets, and the buildings on them, disappeared.

There’s not much of Oliver Street left, just a couple of run-down blocks in Chinatown between Chatham Square and Madison Street, where it dead-ends. It preserves a row of humble, three-story brick houses, currently looking rather forlorn and exhausted, showing every day of their more than a century’s existence. A brass plaque on the wall of 25 Oliver identifies it as the Alfred E. Smith House, listed on the National Historic Register. Al didn’t grown up there, as is sometimes averred. But he lived there a long time and raised his own kids there as a young politician. Had he succeeded in his bid to become the first Irish Catholic President of the United States, 25 Oliver Street could have become a site of American mythology to rival Abe Lincoln’s log cabin. But Al didn’t make it, 25 Oliver is in bad need of a paint job, and today’s mostly Chinese neighbors pass it without a glance.

His father, also named Al Smith, grew up on a block of Oliver Street closer to the river that no longer exists. Al Sr. was a brawny, handsome, wide-mustached working man, a cartman, or hauler of goods, with a horse-drawn truck. After his first wife died he married a girl who’d grown up near the stables at Dover and Water Streets where he kept his horses. (Her parents had come from Ireland on a clipper ship of the famous Black Ball Line that pioneered the Liverpool to New York run. They found rooms to let three blocks from where they stepped ashore and never ventured farther into America.) Al Jr. was born at 174 South Street on December 30 1873, above a little grocery store. He grew up as the Brooklyn Bridge was built. In old photographs it vaults right over the rooftop of the small, narrow house. That whole block has long since disappeared.

As Al remembered it later the waterfront was the neighborhood kids’ playground – there weren’t any others. The rigging of the ships at the docks was their jungle gym. They dove for green bananas that dropped over the side, and bought their pets from sailors who’d carried them up from South America and the Caribbean. At one point Al kept a goat, four dogs, a parrot and a monkey in the South Street attic. He never lost his classic New Yawk accent, salting his speech with dese, dem and youse like a true Bowery Boy.

In 1886 Al Sr. worked himself to death at the age of forty-six, when Al Jr. was twelve. His mother took a job at an umbrella factory and brought home piece-work. Al worked after school delivering newspapers and helping his sister run their landlady’s candy store in the basement where they now lived on Dover Street. He left the St. James school at the end of the seventh grade, when he was fourteen, and never went back. As a teen he worked a number of jobs, including twelve-hour days, six days a week, at the Fulton Fish Market. One of his tasks was to stand in a lookout and watch for the fishing fleet pulling into the harbor. You could tell how much of a haul they were carrying by how low they rode in the water. Later, when fellow politicians, who were mostly lawyers, bragged to him about matriculating from the U of This or That, he’d reply that he graduated from FFM. He grew up quick. By fifteen he was frequenting the neighborhood’s saloons, drinking beer, smoking cigars with the other men.

He was still too young to vote when he started hanging out at the Downtown Tammany Club, around the corner from Oliver Street at 59-61 Madison. It had something of the look of a volunteer fire hall. Men from throughout the neighborhood streamed up the wide stairs and under the double-arched entry into the meeting hall where politics was discussed, elections fixed, jobs and favors dispensed. It was later knocked down for the playground of P.S. 1, also known as the Alfred E. Smith School. Tammany was starting to purge itself of its most corrupt scoundrels, and young Al Smith fell in with the reformist wing. This led to his first patronage job as a process-server, tracking people down to hand them summonses and subpoenas.

He came under the wing of Big Tom Foley, for whom nearby Foley Square was named. Foley operated a very popular saloon at Oliver and Water Streets. In her 1956 memoir of her father, The Happy Warrior, Al’s daughter Emily remembered Foley as “a genial, smooth-shaven, moonfaced man” who was very well liked and highly respected in the neighborhood – a dude in the ward, as Ned Harrigan would have said. Although he lived uptown at Thirty-Fourth Street Foley spent most of his time in and around the saloon and was active in local politics and the St. James parish. As he thrived financially and politically he spread his good fortune around the neighborhood, the way a successful Tammany man was supposed to. When Smith was a boy he and other kids would flock around Foley on the street, and he’d hand each a nickel, which seemed like a fortune to them. (Years later, Al would frequent a popular barbershop in the ward, run by an immigrant from Salerno who played Caruso on the Victrola. Bartolomeo’s runty, homely son lathered the customers before his dad shaved them. Al once tipped the kid a nickel. Instead of spending it on a lemon ice or a Charlotte Russe, the boy, Jimmy Durante, saved it as a souvenir.)

In 1903 Foley anointed the twenty-nine-year-old Smith to be the Democrats’ nominee for what was then the Second District of the State Assembly. Smith appeared before a crowd of cheering neighbors and Tammany stalwarts in a suit he’d just ironed in the kitchen of his Peck Slip apartment. His other suit was in mothballs. As the Tammany Democrat candidate he was a shoo-in, handily beating a Republican, a Socialist, and a Prohibition candidate, who got five votes.

Smith spent the next twelve winters as an assemblyman, shuttling from the Lower East Side to Albany, where he’d live during the weeks while the legislature was in session, returning home on weekends. His re-elections were always sure things. The affable guy with the honking voice and the taste for suds and stogies was liked and admired by all his constituents, not just his fellow Micks. Besides Durante, another of his fans was a Jewish teenager from up on Henry Street, Izzy Iskowitz, who volunteered to make sidewalk stump speeches for him at re-election time. They were in effect the first public appearances by the performer later known as Eddie Cantor.

In 1907 Smith moved his family, which would grow to five kids, to 25 Oliver Street, which he rented from the parish; the rectory was next door at 23. Emily recalled that they couldn’t afford many luxuries on her father’s salary of a hundred and twenty-five dollars a month, but they weren’t poor. They took summer vacations on the beach at Far Rockaway in Queens, and enjoyed an occasional family dinner at the then-new Knickerbocker Hotel in Times Square, followed by a trip to the nearby Palace Theatre, the flagship of vaudeville houses from the 1910s until vaudeville’s end. On Sunday mornings after church they’d often walk across the Brooklyn Bridge to visit family on Middagh Street in Brooklyn Heights. Sunday evenings the Smiths would have friends over, including another young assemblyman, Jimmy Walker, and his (soon to be beleaguered) wife. Jimmy, who’d started out an aspiring Tin Pan Alley songwriter before his father pushed him into politics, would sit at the Smiths’ piano and play songs like his one bona-fide hit, “Will You Love Me in December as You Do in May?”

Along the way Al Smith began to sport the brown derby that, along with the cigars, became a familiar feature of his public image. He was elected governor in 1918. Emily remembered the children’s wonderment when the family moved from the little house on Oliver Street to the executive mansion in Albany, with its reception room, music room, library, breakfast room, a dinner table that could seat thirty, and nine bedrooms, each with its own bathroom. Plus a small army of servants who magically appeared at the press of a bell. When Smith lost his reelection bid in 1920 and the family returned to Oliver Street, the kids glumly went back to sharing bedrooms and fighting over the two bathrooms.

Smith was briefly convinced his political career was over. Yet that same year, at the Democrats’ national convention in San Francisco, his name was put up for the first time as a possible presidential candidate. As the band struck up “The Sidewalks of New York” (rather than the Ned Harrigan song Smith wanted), the entire convention began to sing along, then waltz in the aisles, and partied for the next hour as the band played one popular tune after another, finally getting to Harrigan’s “Maggie Murphy’s Home.” Ever the skeptic, H. L. Mencken thought it was the free-flowing bootleg bourbon – Prohibition had gone into effect six months earlier – rather than political conviction that got them all going, and in fact Smith was not yet a serious contender. The Democrats nominated Ohio governor James Cox, with Franklin D. Roosevelt as his running mate. Warren G. Harding trounced them.

New Yorkers gave Smith the governor’s mansion back in 1922, and the Smiths moved out of Oliver Street for the last time. In June 1924, the Democrats held their convention at Madison Square Garden. Roosevelt delivered the speech throwing Governor Smith’s brown derby in the ring. Smith and Roosevelt were the most unlikely bedfellows. Smith liked to tell a bitterly humorous story about the first time he’d called on Roosevelt in his mansion back in 1911, and the butler didn’t want to let him in the door. A vast gulf of class and breeding separated the former fishmonger from the upstate aristocrat born with silver spoons in every orifice. Roosevelt had grown up in a household where he was surrounded by German and Scandinavian servants, because his father refused to hire the Irish or Negroes. And he had the upstater’s severe mistrust of anyone associated with Tammany. Yet the two had gotten over their differences and become allies, if not quite friends, working together for reform in the state.

Smith loyalists once again erupted in a prolonged celebration at the end of Roosevelt’s speech, but in fact Democrats at the convention were deeply divided between the urban progressives who backed Smith and the rural and Southern conservatives who were convinced that the nation would never elect an Irish Catholic from Jew Yawk. Smith’s background was in fact a serious drawback at a time when Republicans still characterized Democrats as the party of “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion.” Like many other New York politicians, Smith had been against Prohibition, which condemned him with its supporters around the country. He was only a mildly liberal Democrat, but any Democrat running in the Republican boom times of the Roaring Twenties was running up a very steep hill. And finally, there was the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had been reborn in the 1910s, riding new waves of xenophobia, racism and anti-communism, and was a much bigger and stronger presence in 1924 than it had ever been. The Klan issued a “Klarion Kall for a Krusade” against Smith should he be nominated.

The convention dragged on for two weeks and more than a hundred ballots. Chairman Cordell Hull passed out a few times from the summer heat – air conditioning was still a way off. Another Lower East Sider, Irving Berlin, was a celebrity observer. He dashed off a campaign song, “We’ll All Go Voting for Al.” It didn’t help. The more conservative John W. Davis got the nomination and went on to lose badly to Calvin Coolidge. (Berlin would soon write a more successful campaign song for Al’s friend, “It’s a Walk-In with Walker.”)

In 1928 the Democrats finally handed Smith their presidential nomination. There were some faint reasons for them to be hopeful. The Klan had peaked and was slipping back into being merely an ugly nuisance on the lunatic fringe. People were tiring of Prohibition and considered it a failed experiment. On the other hand, the nation was still enjoying unprecedented prosperity under the Republicans, except in the farm belt. Farming was a much bigger sector of the economy then than now, and farmers had effectively been in their own depression since the end of World War One. They weren’t likely to be convinced that a guy from New Yawk would do better for them than a Republican. And Smith’s opponent was not just any Republican. He was Herbert Hoover, one of the most popular figures in America at the time, an orphan from Iowa who by hard work and smarts had achieved the American dream of riches and power. He was also known as a great humanitarian, the American who had almost singlehandedly organized a massive food relief program for starving Belgians during the war.

As the campaigns rolled out, Hoover – who was coincidentally the first Quaker candidate – never played the religion card. But the Klan and other anti-Catholic fringe groups did, and so did more mainstream Protestant spokespeople, somberly questioning if a Catholic could be the leader of the country when he owed his allegiance to Rome first. In the end, though, it was probably the combination of Hoover’s popularity and the unprecedented boom times – the big crash wouldn’t come until October 1929 – that sank Smith. He ran as the friend of the little guy at a time when a lot of the little guys, except for those farmers, were doing all right. Hoover gave Smith a severe shellacking, carrying all but eight states. Most galling of all, even the state of New York went for him.

A private citizen again in 1929, Smith accepted a job as president of the corporation that would build the world’s tallest skyscraper, the Empire State Building. Construction proceeded even after the stock market crashed that October, and the building opened in May 1931, with Smith and Governor Roosevelt leading the ceremony. Listeners to the live radio broadcast heard Smith ballyhoo the edifice as “the tallest thing in the world today produced by the hand of man.” His Lower East Side roots still showed in the way he pronounced world woild. To the average New Yorker the building was a towering beacon of optimism in what had become very dark times, but as a business venture it was a bust. Unlike the successful Chrysler Building that had opened in 1930, the Empire State Building had so few tenants signed up that wags nicknamed it the Empty State Building. It would continue to bleed red ink for twenty years.

Despite the thrashing in 1928, Smith entertained hopes for the Democratic nomination again in 1932, which put him at odds with another contender, Roosevelt. Without officially declaring himself, Smith made it clear he’d accept the nomination if offered, and his supporters at the convention were as boisterous and loud as ever. But he’d had his shot. Roosevelt carried the convention, and the two patched up their differences in public so that the Democrats could beat Hoover that fall.

As Roosevelt’s New Deal policies grew more radical in extending federal power during his long presidency, Smith’s opinions grew more conservative and oppositional. He helped found the anti-New Deal, pro-business Liberty League, making him a pariah among Democrats. He even went completely off the reservation to back Republicans Alf Landon in 1936 and Wendell Willkie in 1940. Roosevelt trounced them both. Once America entered the war, however, Smith was one of the commander-in-chief’s most diligent boosters on the home front.

When his wife died in May 1944 Smith went into broken-hearted decline. He died of cirrhosis that October, a couple months shy of his seventy-first birthday. The whole city mourned his passing. Besides the little house on Oliver Street and P.S. 1, you still see his name all over his lowest East Side neighborhood, on a playground, a rec center, and a giant public housing complex.

by John Strausbaugh

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Maybe she’s the one who’s worthless”

My husband and I fought last night and I just broke down and started crying. I’ve been feeling so insecure about our relationship, still. It hasn’t gone away, and I felt like we were growing further apart because of my actions. I told him I thought he was angry and blaming me for Alice, that I felt like he hated being around me anymore, that I felt worthless.

He stayed quiet and didn’t say anything for a few minutes before asking, “So, you think you’re worthless?”

“She-who-will-not-be-named-like-Voldemort treated me like I’m worthless.”

“No! You are not worthless! Maybe she’s the one who’s worthless.”

He went on and on to say that no matter what, he would be by my side and that’s where he would remain. That he made the vows, not she-who-will-not-be-named-like-Voldemort, and I shouldn’t be worried about her, that she isn’t special and “fuck that bitch” was appropriate considering the circumstances.

I sat in the passenger side of the vehicle as we drove on the interstate, with an “Ah-Ha!” moment going on in my head that I never contemplated before: Was my friend actually worthless?

When it came to writing, I was constantly (and still am) working on my craft, while she kept in her safe zone and never tried to write anything different than “this girl has a curse/gift/item/special power/golden vagina, and this dude is stuck following her.” not that mine are that much different, but at least the chicks in my stories aren’t just powerful in a Mary Sue fashion.

When it came to drawings, I was showing off my skills to her so she could see what practice and hard work could lead to, because I’ve seen “her drawings” (which weren’t actually her’s I found out later) and thought she should keep it up. She never did and said “I haven’t done it in so long, I don’t want to waste my time. It’ll be bad anyway.” She just gave up a talent that could have been worked on to be something wonderful because she didn’t want to hurt her own ego.

When it came to life, I’ve worked so many jobs, and I can only remember her actually working two jobs, and both of them were McDonald’s. I’ve always worked for a living, where as she would say, “oh, you’ll get a job easier than I ever could.” or “oh, I can’t work anymore, I can’t deal with people.” Bitch, you have to go outside in order for that shit to even make sense. You’ll get a job easier if you actually go look for a job and apply for it, and you can’t work around people if you never leave your house.

(Note: She would always say her “issues” were the reason why she couldn’t be around people, or even why she couldn’t work, while being surrounded by a shit ton of people and enjoying it; while I would be cringing in a corner feeling awkward cause I only know two people and there’s no tacos or cake available)

I’ve been to several different countries, served in the military, performed my duties to the best of my abilities and was rewarded for it, learned to play piano and currently working on violin and guitar, bought my first vehicle and learned to drive all over, and traveled to different states in that same vehicle, I’ve gotten drunk on the strongest liquors in fancy, overpriced hotels and mansions like the trash loser I am, I’ve cursed out authority when they tried to fuck over my peers and subordinates, I’ve taken care of the elderly, I’ve worked charity and volunteer work, I’ve supported those who needed it, I’ve given funds and funds to others who were in need because it was the right thing to do, I’ve learned three different languages just for the fuck of it because I hate Spanish (Still don’t know why that is though. Just sounds too tricky for my ears, I guess), I found the perfect man and have been with him nearly 8 years come July, we had a child together, and we kick ass at paying our bills and rent on time.

All she has done is get married and had a kid. If she hadn’t done any of that, I don’t know what she would be doing or where she would even be living at, now that I think about it. She’s lived in different states as well, but she’s never actually lived by herself. It was always either with a boyfriend or a friend or family member. I don’t know if she’s actually lived on her own before. I have many times, both for and against my will. In a way, she’s just like her brother; using other people to live off of because she doesn’t want to take care of herself.

When it came down to the two of us, I was always the one doing something, while she was the one just there, stuck. She stayed in place, almost on purpose, which makes me think that maybe it really wasn’t that she was mad I never left my husband, but because I didn’t pay as much attention to her. Then again, I’m starting to also think she got prego cause of her sister in law. she had her daughter first, then she-who-will-not-be-named-like-Voldemort got prego.

It was like she decided my personality and behavior got boring because she met someone who was doing something new that she had no experience of, and decided to be part of that. She even decided my daughter was worthless to her, but she had been doing that since I got pregnant. Trying to get into heaven doesn’t help too much either, not in her case anyway.

I keep looking at the differences between us, and I can’t think of a time when I was worthless. There were times when I was no longer useful, but that’s not the same as worthless. Just because you don’t have a nail sticking out doesn’t mean that a hammer is a useless tool. I feel guilty for talking of all of my deeds, but listing them out now is helping more than you would believe. When someone makes you feel worthless, only because they have nothing of worth to share, to demonstrate, to preserve and educate others with, I guess you have to compare lives.

I’ve measured that the things I’ve done in my short 30-something shit life keep me from ever being worthless. No matter what happens, I can adapt myself to learn anything because I want to learn anything and everything I can. She-who-will-not-be-named-like-Voldemort and whether or not she actually can be considered worthless now, I don’t know. It’s not like she’s done much with herself over her life--Which is fine, cause people live their lives the way they want.

But to call me toxic after all of the things I’ve done over the years, all because my daughter because my focus in life, really doesn’t tell me she was worth anything at all. Not anymore anyway. I have to keep talking as much shit about this crap so i don’t let my brain forget. Of course, my brain has been telling me what to do and how to do it as of late. Been pretty sharp as of late, actually, surprisingly.

Either way, At least I can get this out. At least I know I’m not worthless.

0 notes