#kropotkin

Text

#196#r/196#gardening#communism#kraz mazov#karl marx#kropotkin#conquest of tomatoes#conquest of bread#socialism#anarchism#anarcho-goblinism#anarcho-imgonnaeatyourfuckingvegetablesism#YUM!

832 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, been wanting to read Kropotkin for a while but I dont know where to begin, any suggestion/recommendation? Anarchist Morality and Mutual Aid seem to be the most popular...

I always really liked An Appeal To The Young as a starting pont, because its just a bunch of texts addressing young students and workers, basically asking them what they want from life and telling them to think about why they should start dedicating their whole lives to the accumulation of capital and personal gain.

67 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“To remain the servant of the written law is to place yourself every day in opposition to the law of conscience, and to make a bargain on the wrong side”

- Peter Kropotkin

387 notes

·

View notes

Text

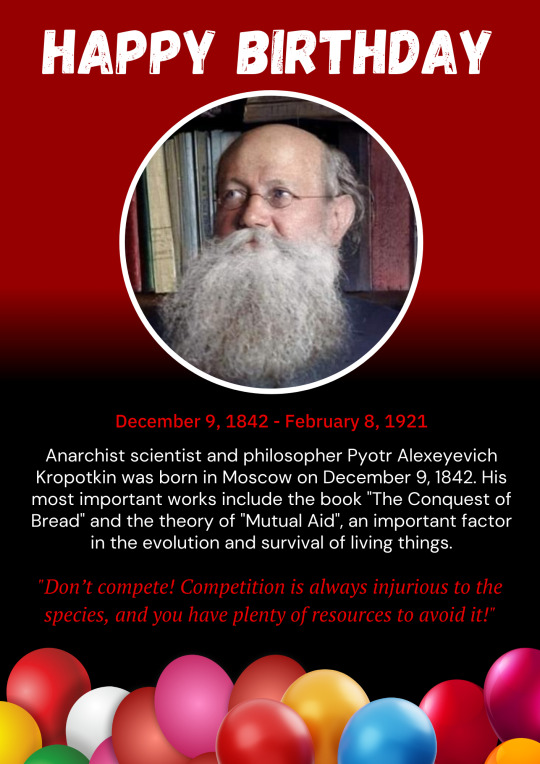

Today is the birthday of Anarcho-communist scientist and philosopher Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unrueh, dir. Cyril Schäublin (Switzerland 2022)

#unrueh#unrest#désordres#cyril schäublin#film#cinema#movies#Switzerland#2022#clockwork#anarchism#kropotkin#capitalism#time

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was talking to a fellow Stirner-enthusiast once and he asked who else I was influenced by. I mentioned Kropotkin and he said he was never able to get past Kropotkin's "idea that the medieval burgs were anarchist." This was not actually an idea Kropotkin had.

Kropotkin never claimed the medieval burgs were anarchist. He just wrote that they had a relatively high degree of decentralization and self-government compared to the modern nation-state.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

32 notes

·

View notes

Quote

We, in civilized societies, are rich. Why then are the many poor? Why this painful drudgery for the masses? Why, even to the best paid workman, this uncertainty for the morrow, in the midst of all the wealth inherited from the past, and in spite of the powerful means of production, which could ensure comfort to all in return for a few hours of daily toil?

Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

santa claus

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

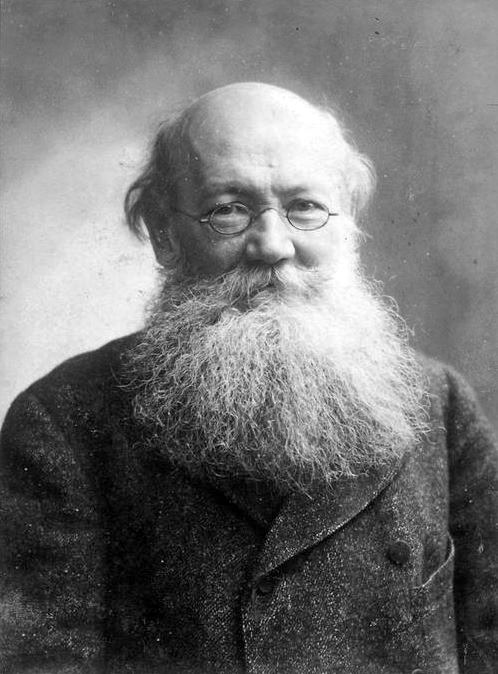

[Video] Rare footage of anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin in 1917 at the age of 74

Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin, (born December 9, 1842, Moscow, Russia—died February 8, 1921, Dmitrov, near Moscow), Russian revolutionary and geographer, the foremost theorist of the anarchist movement. Although he achieved renown in a number of different fields, ranging from geography and zoology to sociology and history, he was eternalized for the life of a revolutionist.

Early life and conversion to anarchism

The son of Prince Aleksey Petrovich Kropotkin, Peter Kropotkin was educated in the exclusive Corps of Pages in St. Petersburg. For a year he served as an aide to Tsar Alexander II and, from 1862 to 1867, as an army officer in Siberia, where, apart from his military duties, he studied animal life and engaged in geographic exploration.

Kropotkin’s findings won him immediate recognition and opened the way to a distinguished scientific career. But in 1871 he refused the secretaryship of the Russian Geographical Society and, renouncing his aristocratic heritage, dedicated his life to the cause of social justice. During his Siberian service he already had begun his conversion to anarchism—the doctrine that all forms of government should be abolished—and in 1872 a visit to the Swiss watchmakers of the Jura Mountains, whose voluntary associations of mutual support won his admiration, reinforced his beliefs. On his return to Russia he joined a revolutionary group, the Chaiykovsky Circle, that disseminated propaganda among the workers and peasants of St. Petersburg and Moscow. At this time he wrote “Must We Occupy Ourselves with an Examination of the Ideal of a Future System?,” an anarchist analysis of a postrevolutionary order in which decentralized cooperative organizations would take over the functions normally performed by governments.

He was imprisoned in 1874 for his ideas but was freed by his comrades in a sensational escape 2 years later, fleeing to western Europe, where his name soon became revered in radical circles. The next few years were spent mostly in Switzerland until he was expelled at the demand of the Russian government after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II by revolutionaries in 1881. He moved to France but was arrested and imprisoned for 3 years on trumped-up charges of sedition. Released in 1886, he settled in England, where he remained until the Russian Revolution of 1917 allowed him to return to his native country.

Philosopher of revolution

Kropotkin’s aim, as he often remarked, was to provide anarchism with a scientific basis. In Mutual Aid, which is widely regarded as his masterpiece, he argued that, despite the Darwinian concept of the survival of the fittest, cooperation rather than conflict is the chief factor in the evolution of species. Providing abundant examples, he showed that sociability is a dominant feature at every level of the animal world. Among humans, too, he found that mutual aid has been the rule rather than the exception. He traced the evolution of voluntary cooperation from the primitive tribe, peasant village, and medieval commune to a variety of modern associations—trade unions, learned societies, the Red Cross—that have continued to practice mutual support despite the rise of the coercive bureaucratic state. The trend of modern history, he believed, was pointing back toward decentralized, nonpolitical, cooperative societies in which people could develop their creative faculties without interference from rulers, clerics, or soldiers.

In his theory of “anarchist communism,” according to which private property and unequal incomes would be replaced by the free distribution of goods and services, Kropotkin took a major step in the development of anarchist economic thought. Kropotkin envisioned a society in which people would do both manual and mental work, both in industry and in agriculture. Members of each cooperative community would work from their 20s to their 40s, four or five hours a day sufficing for a comfortable life, and the division of labour would yield a variety of pleasant jobs, resulting in the sort of integrated, organic existence.

To prepare people for this happier life, Kropotkin pinned his hopes on the education of the young. To achieve an integrated society, he called for education that would cultivate both mental and manual skills. Due emphasis was to be placed on the humanities and on mathematics and science, but, instead of being taught from books alone, children were to receive an active outdoor education and to learn by doing and observing firsthand, a recommendation that has been widely endorsed by modern educational theorists. Drawing on his own experience of prison life, Kropotkin also advocated a thorough modification of the penal system. Prisons, he said, were “schools of crime” that, far from reforming the offender, subjected him to brutalizing punishments and hardened him in his criminal ways. In the future anarchist world, antisocial behaviour would be dealt with not by laws and prisons but by human understanding and the moral pressure of the community.

Kropotkin combined the qualities of a scientist and moralist with those of a revolutionary organizer and propagandist. For all his mild benevolence, he condoned the use of violence in the struggle for freedom and equality, and, during his early years as an anarchist militant, he was among the most vigorous supporters of “propaganda by the deed”—acts of insurrection that would supplement oral and written propaganda and help to awaken the rebellious instincts of the people. He was the principal founder of both the English and Russian anarchist movements and exerted a strong influence on the movements in France, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Return to Russia of Peter Alekseyevich Kropotkin

Events took an unexpected turn with the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in 1917. Kropotkin, by this time age 74, hastened to return to his homeland. When he arrived in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in June 1917 after 40 years in exile, he was greeted warmly and offered the ministry of education in the provisional government, a post he brusquely declined. Yet his hopes for the future were never brighter, because in 1917 the organizations that he thought might form the basis of a stateless society—the communes and soviets, or soldiers’ and workers’ councils—suddenly began to appear in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

With the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, however, his earlier enthusiasm turned to bitter disappointment. “This buries the revolution,” he remarked to a friend. The Bolsheviks, he said, have shown how the revolution was not to be made—that is, by authoritarian rather than libertarian methods. Kropotkin’s last years were devoted chiefly to writing a history of ethics, one volume of which was completed. He also fostered an anarchist cooperative in the village of Dmitrov, north of Moscow, where he died in 1921. His funeral, attended by tens of thousands of admirers, was the last occasion in the Soviet era when the black flag of anarchism was paraded through the Russian capital.

Kropotkin’s life exemplified the high ethical standard and the combination of thought and action that he preached throughout his writings. He displayed none of the egotism, duplicity, or lust for power that marred the image of so many other revolutionaries. Because of this he was admired not only by his own comrades but by many for whom the label of anarchist meant little more than the dagger and the bomb. The French writer Romain Rolland said that Kropotkin lived what Leo Tolstoy only advocated, and Oscar Wilde called him one of the two really happy men he had known.

#κροπότκιν#kropotkin#piotr kropotkin#peter kropotkin#russia#russian#anarchist#anarchism#anarchy#newsreel#old#old film#old movie#black and white#Youtube

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

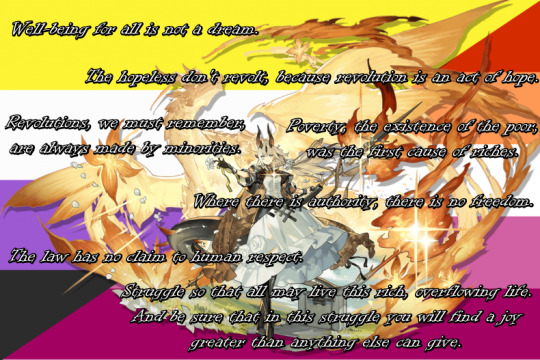

My political philosophy in one image

#arknights#reed#kropotkin#if Reed is an anarchist does that make Eblana a tankie#please don't think too hard about that

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Love to see Marxists still arguing about measuring or not measuring value when a non-marxist like Kropotkin already came up with the better position way back in 1892:

You can't measure it and shouldn't want to even if you could. Expropriate everything now and base life on need."

#marxist leninist#marxist theory#marxism#marxist feminism#marxist#peter kropotkin#kropotkin#lol#lmao#lulz#hehe haha#haha funny#haha lol#haha#life#needs#wants#endure and survive#survive#politics#neoliberal capitalism#capitalist dystopia#capitalist bullshit#capitalist hell#capitalism#ausgov#auspol#tasgov#taspol#politas

9 notes

·

View notes

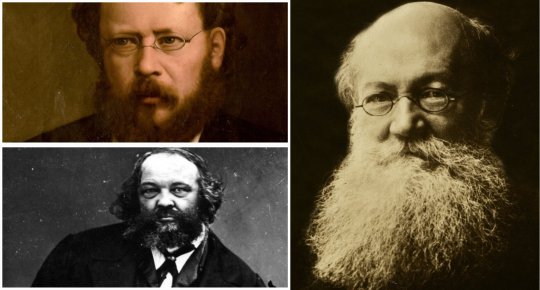

Photo

“The Anarchist formerly known as Prince”

281 notes

·

View notes

Text

«Proudhon, Bakunin, Kropotkin no eran "amoralistas" como algunos de los rumiadores sosos de Nietszche en Alemania que se titulan anarquistas y son bastante modestos con considerarse "super-hombres". No han construido con habilidad una llamada "moral señorial y esclava" de la que toda clase de conclusiones se pueden sacar, pero al contrario se preocuparon de investigar el origen de los sentimientos morales en el hombre y lo hallaron en la convivencia social. Estando lejos de dar a la moral un significado religioso y metafísico, vieron en los sentimientos morales del hombre la expresión natural de su existencia social que se cristalizó lentamente en determinadas conductas y costumbres y servía de pedestal para todas las formas de organización que salían del pueblo.»

Rudolf Rocker: Anarquismo y organización. Ideas, pág. 6. Barcelona, 1982.

TGO

@bocadosdefilosofia

@dies-irae-1

#rudolf rocker#proudhon#bakunin#kropotkin#nietzsche#anarquismo#moral#moral señorial y esclava#moral de los señores#moral de los amos#moral de los esclavos#amoralismo#amoralistas#sentimiento moral#conducta#costumbre#organización#super-hombre#superhombre#pueblo#existencia social#formas de organización#amoral#amoralidad#anarquismo y organización#anarquismo individualista#teo gómez otero

10 notes

·

View notes