#jim mcdivitt

Photo

Remembering NASA astronaut Jim McDivitt (June 10, 1929 – October 13, 2022), who has died at the age of 93.

Jimbo was a USAF combat and test pilot before being selected as a NASA astronaut in 1962. He flew Gemini IV in 1965 with his best friend Ed White, becoming the first American astronaut to command his first spaceflight. In 1969, he was the commander of Apollo 9, the third manned mission of the Apollo program. Jim also served as the Apollo Spacecraft Program Manager until his retirement from NASA in 1972.

In addition to being a brilliant engineer and pilot, Jim was a husband, father, and friend. He brought his wit, kindness, and sense of humor to the astronaut corps and paved the way for future explorers. May his memory be a blessing. Ad astra, Jimbo 💙

#jim mcdivitt#astronauts#NASA#apollo#55 years since he's been with ed... hope they're partying together again <3

222 notes

·

View notes

Note

Happy birthday! My Mercury to my Gemini!

Ok

Headcanons for the Astros watching top gun.

ackkkk thanks!! i've been trying not to go insane today :)))

NASA Astronauts Watching Top Gun: (spoilers!)

i guarantee that these dudes are going to point out every detail of this movie

and you can quote me on that

the good details

the bad details

all of it

you can count on a very salty Frank Borman to shit on the Navy pilots

"see?! crap like that would never happen in the AF!"

Jim Lovell would develop a slight crush on Tom Cruise

even Maverick does something really dumb in the movie, Jim will defend him every time

which will piss off Frank to no end

Jim McDivitt will be the Wikipedia Bitch of this movie

he's going to be doing alllll the research of the aircraft and training used for the movie

Neil Armstrong will be the dude who just sits silently through the whole movie, only occasionally smirking at a funny line

he already knows all the trivial facts that McDivitt is looking up

but he lets him go ahead and rattle off facts that nobody asked for

Mike Collins whistles anytime Jennifer Connelly comes on screen

instead of mourning the loss of Goose at the end, Mike and McDivitt are the ones saying "well, what he could've done was ..."

or "if it we're me, and i'm not saying it would be, but..."

Frank can't stand the sad scenes bc we all know he's just a softie

Jim Lovell is beyond happy when Maverick and Ice Man finally become friends

"I told you this would happen!"

Their overall rate: 9.5/10

Low because emotions ick :/

Surprisingly high?bc of the devotion to aircraft and piloting detail and a bias for the Navy :)

#enjoy!#nasa headcanons#jim lovell#frank borman#neil armstrong#mike collins#jim mcdivitt#top gun#birthday2022#headcanons

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bidding farewell to an unsung legend

R.I.P. James A. McDivitt, test pilot and astronaut. He passed away on October 13 and somehow it flew utterly beneath my radar.

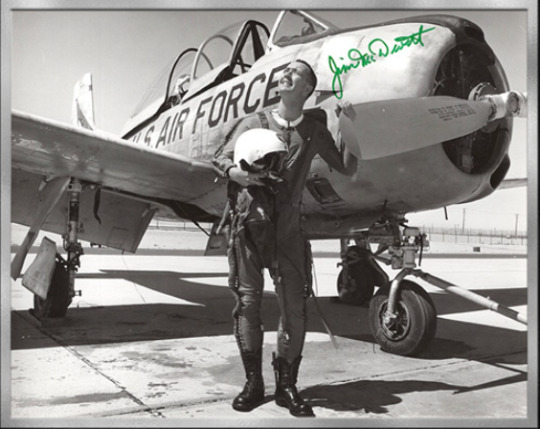

Jim McDivitt was a Korean War combat pilot, and earned a Bachelors in Aeronautical Engineering from University of Michigan, a spot in the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School, and was a member of the inaugural class at the Aerospace Research Pilot School. He had over 2,000 hours in jets (here he is striking a heroic pose with a decidedly not-heroic T-28).

Later Jim was selected as a member of NASA Group 2, known as “the New (or Next) Nine.” They were chosen to augment the Original Seven for the Gemini program and beyond. From lower left, they are Jim Lovell*, Elliot See, Ed White, Neil Armstrong**, Frank Borman*, John Young**, Tom Stafford*, Pete Conrad**, and that's Jim McDivitt front and center.

(*) Six of this group went to the Moon and three (**) of them walked on it; two more died in tragic accidents before getting their chance to go. None of them were Jim McDivitt, so his career is often overlooked.

Thanks to a thing called “the pecking order,” the Mercury Seven were automatically first in line when it came to getting the mission assignments, but with the two-man Gemini program starting up, that meant Chief Astronaut Deke Slayton could assign some of these new guys to fill the right seat while the Mercury veterans commanded the mission. John Young was the first guy from Group 2 to fly, paired with America's second man in space Gus Grissom, for the first crewed Gemini mission: a simple (well, as simple as anything related to spaceflight can be, that is) shakedown flight called Gemini 3.

But Gemini 4 (June 1965) was much more ambitious, and McDivitt was given command, making him the first rookie to command a crew.

Flying right seat (left, in this photo) was his fellow Group 2 buddy and former University of Michigan schoolmate Ed White. The mission plan was packed; it was going to be four days long— longer than all of America's previous spaceflights put together. They were going to practice celestial navigation with a sextant and attempt a rendezvous with a spent rocket stage. And thanks to cosmonaut Alexei Leonov having become the first man to leave his spacecraft while in orbit earlier that year, a spacewalk was hurriedly added to Gemini 4, too.

This task fell to White, as of course McDivitt would be responsible for flying the spacecraft.

McDivitt's pictures of White during his extravehicular activity (EVA) are among some of the most spectacular in all of NASA's history.

BTW the so-called controversy of Ed White becoming too enamored of the void of space to come back into the spacecraft is bullshit. The comms setup was that the guy outside could only hear the guy inside, not the ground, and they kept stepping on each others’ transmissions.

Next up for Jim would be command of Apollo 8, the first crewed test of the Apollo Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit. Along for the ride were Group 3 astronauts Dave Scott, a veteran of Gemini 8, as command module pilot (CMP), and rookie Rusty Schweickart, as LMP.

Apollo 7 (Wally Schirra, Walt Cunningham, Donn Eisele) had successfully tested the CM in Earth orbit in October of 1968. But just as the Soviets had changed the Gemini 4 mission with Leonov's spacewalk, they changed the remaining Apollo schedule with their Zond spacecraft, which was capable of flying around the moon and back. They had one ready to launch, and if successful, they could say “We got there first; that means we won the space race. Ешьте дерьмо, неудачники!” And Apollo 8’s LM was nowhere near ready to fly.

So Deke and the higher-ups at NASA decided to send Apollo 8 to the moon first, by itself, without the LM. Deke didn't want to lose Jim’s crew’s experience with their lander, so he swapped them with the crew of Apollo 9: Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders, who went on to spend Christmas 1968 in lunar orbit (famously reading from Genesis on Christmas Day).

In March of 1969 the CM Gumdrop (Dave Scott thought it looked like a piece of candy when it arrived at the Cape wrapped in cellophane) and LM Spider (well, just look at it!) were launched and tested thoroughly in Earth orbit. When Jim and Rusty flew off in Spider they became the first men to fly a spacecraft which could not land if things went wrong (weight was such an issue that the cabin walls were made of layers so thin that if you dropped a screwdriver it would puncture them, and of course it had no heat shield to get through Earth's atmosphere).

The crew put Spider through its paces; firing the descent engine several times, testing its ability to maneuver with the thrusters, and firing the ascent engine to get back to Dave in Gumdrop. Rusty also did a modified spacewalk to test the lunar EVA suit (sadly, he was spacesick at the beginning of the mission and as a result, never got to fly again).

After retiring from active flight status, Jim served as NASA’s Spacecraft Program Manager for a few years and retired from the Air Force in 1972 with the rank of Brigadier General; he also earned a buttload of Flying Medals, Distinguished Service Medals, and other honors throughout the course of his life.

Jim, Dave, and Rusty reunited in 2019 for the flight's 50th anniversary. With Jim’s passing, the Apollo 8 crew is the last Apollo crew still intact.

Ad Astra, Jim: June 10 1929 - October 14, 2022

1 note

·

View note

Text

Apollo 9 astronauts Jim McDivitt and Rusty Schweickar

156 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apollo 9 astronauts Rusty Schweickart, Dave Scott and Jim McDivitt in front of their Saturn V Rocket. Their mission (March 3–13, 1969) was the third human spaceflight in the Apollo program. Unlike the missions before and after them, they did not leave Earth orbit and go to the moon. But it was important because it was the first test of a complete Apollo spacecraft (command and service module, lunar module and the Saturn rocket). During the mission, the crew tested the LEM and successfully performed a rendezvous and docking with the command module. The results of this mission proved the lunar module and landing craft were ready to go to the Moon on Apollo 10.

The excellent Tom Hanks/Ron Howard miniseries From the Earth to the Moon has a great episode that showcases Apollo 9 called "Spider" - the title comes from the nickname the astronauts gave the lunar lander. The show of course features the mission but does a superb job showing the numerous challenges the Grumman engineers had in designing, building and testing the lander.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jim McDivitt’s F-86 Saber. McDivitt flew 145 combat missions in the Korean War, as well as commanding Gemini IV and Apollo IX.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Christmas Eve 1968, as commander of Apollo 8 – the first manned lunar orbital mission – Frank Borman, who has died aged 95, came out with words that, alongside Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind”, from Apollo 11 in 1969, and Jack Swigert and Jim Lovell’s “OK, Houston, we’ve had a problem”, from Apollo 13 in 1970, defined an era.

In that moment before the moon programme became mundane, when astronauts were prime time, Apollo 8’s broadcast ended with the crew – Bill Anders, Lovell and Borman – reading the story of Earth’s creation as written in the book of Genesis.

It was Borman’s conclusion, “Good night, good luck, a merry Christmas and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth”, that clinched it. For Gene Kranz, Nasa’s chief of flight control operations in Houston, the phrase was “literally magic. It made you prickly. You could feel the hair on your arms rising, and the emotion was just unbelievable.”

Thus, for some, the traumatic 1968 of the ongoing Vietnam war, the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, and the crushing of Czechoslovakia, had been transcended. From a distance – around 238,855 miles – it was still, apparently, the good Earth.

Around two years earlier, Nasa had been in crisis. On 27 January 1967, Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee had been incinerated on Apollo 1 during a test launch. Borman was appointed to the Nasa board which, that April, reported on the fire, slamming Nasa management and North American Aviation for its “ignorance, sloth and carelessness”.

Borman was then sent to North American’s plant in Downey, California – where drunkenness had been rife – to scrutinise command module redesign. “Borman set them straight,” wrote the second man on the moon, Buzz Aldrin, in Men from Earth (1989). “His shoot-from-the-hip management style – some called it bullying – worked.”

The Mercury programme had put astronauts in space. Gemini – to which Borman had been recruited in 1962 – had honed the business of Apollo: to fulfil President John F Kennedy’s goal of a manned moon landing by the end of the decade. In December 1965, Borman and Lovell had made their space debut with a record 14 days of orbit on Gemini 7, and also made a rendezvous with Gemini 6.

In the wake of the 1967 tragedy there were three unmanned Apollo launches, with mixed results. But in September 1968 the unmanned Soviet Zond 5’s orbit of the moon triggered alarm in the US. The Soviets had launched Sputnik, and the space age, in 1957. The first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, had orbited Earth in April 1961. That, along with the furore around the Bay of Pigs fiasco, had helped propel JFK into making his rash pledge in May 1961.

Seven years on, in autumn 1968, Nasa and the CIA were asking whether history was going to repeat itself. Would a Russian be first around the moon? That October, the Apollo 7 astronauts, Wally Schirra, Walter Cunningham and Donn Eisele, spent a successful, albeit cold-ridden and fractious, 10 days in orbit around the Earth. There were rows with ground control. None of those three would get another mission.

Nasa needed a breakthrough. Rather than the next planned Earth orbit, Apollo 8 was to be sent to the moon and, after the astronaut Jim McDivitt turned down the offer, Borman got the job. On 21 December, following a morale-boosting visit from the aviator Charles Lindbergh, Borman, Lovell and Anders blasted off.

Borman’s greatest fear, wrote Andrew Chaikin in A Man on the Moon (1994), was that the moon mission would be aborted and Apollo 8 would be confined to orbiting the Earth. It did not happen, but en route Borman was afflicted by vomiting and diarrhoea, the detrital consequences of which floated on, to be trapped by paper towels. The three men orbited the moon 10 times in 20 hours, descended to 69 miles above the rock’s surface, and were the first to witness the far side of what Borman called “a great expanse of nothing”.

It was on the fourth orbit that Borman spotted the Earth rising from behind the moon – an image that Anders captured on colour film and became known as Earthrise. “Oh my God! Look at the picture over there. Here’s the Earth coming up,” Borman is recorded shouting in a transcript.

Born in Gary, Indiana, Frank was the son of Edwin Borman, who ran an Oldsmobile dealership, and Marjorie (nee Pearce). The family moved to Tucson, Arizona, where his mother opened a boarding house, and Frank went to the local high school. He first flew as a teenager, in 1943. Seven years later he graduated from West Point Military Academy in New York state.

From 1950 Borman flew F-84 fighter-bombers with the US Air Force. A perforated ear drum denied him Korean war combat experience. In 1957 he gained a master’s in aeronautical engineering from the California Institute of Technology and became an assistant professor of thermodynamics and fluid mechanics at West Point.

Three years later he graduated from the Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards air force base in California. There, his aircraft included the controversial Mach 2 Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. It was in 1962 that, alongside Armstrong, Lovell and others, he became one of Nasa’s Gemini programme “New Nine”. Apollo 8 proved what had been evident to insiders for many years: that the US had won the space race. Borman, Anders and Lovell became Time magazine’s 1968 men of the year.

Having achieved the rank of colonel in the mid-1960s, Borman retired from the USAF and space flight and, after a sojourn at Harvard Business School, joined Eastern Air Lines. By 1975 he was Eastern’s CEO and a year later became chairman. But by the late 70s competition was intensifying, labour relations were deteriorating and Borman – never a diplomat – was in the firing line. He quit the company in 1986 when it was taken over by a corporate raider, and Eastern collapsed five years later.

He and his wife, Susan (nee Bugbee), whom he had married in 1950, moved to New Mexico, where he remained involved in business interests. They later settled in Billings, Montana, where he had a cattle ranch and rebuilt vintage aircraft. A supporter of Richard Nixon and both George Bushes, Borman was a man of brisk views. Among the many targets of his ire were the sound barrier-breaking pilot Chuck Yeager, the Democratic party presidential candidate Michael Dukakis and the scientist Carl Sagan.

He received many honours, including the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 1978, and published his autobiography, Countdown, in 1988.

Susan died in 2021. His sons, Frederick and Edwin, four grandchildren and six great-grandchildren survive him.

🔔 Frank Frederick Borman II, astronaut, born 14 March 1928; died 7 November 2023

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Space history...

Apollo 9 was a test mission in earth orbit of the spacecraft and equipment that would take NASA astronauts to the moon.

One of the activities planned was to rehearse transfer from the LM to the CSM via EVA, should it not be possible to use the tunnel between the two docked module. Here is how it was supposed to be done...

However, LM pilot Rusty Schweickart fell ill with space-adaptation syndrome and it was deemed too risky to attempt the transfer. Schweickart was cleared for an abbreviated EVA on the LM front porch in "golden slippers" foot restraints to test the Apollo EVA spacesuit and backpack.

Here, he's photographed by mission commander Jim McDivitt from inside the LM.

The scales etched into the LM window would be used on future missions to show the commander flying the LM where the computer intended to land.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ad Astra James McDivitt

2022, October 13, USAF BrigGeneral, former NASA astronaut James McDivitt passed away aged 93.

Jim McDivitt, selected a NASA astronaut in 1962, commanded Gemini IV the first U.S. mission to conduct a spacewalk before leading the first test flight of the Apollo moon lander in Earth orbit.

This photo shows McDivitt post-flight Gemini IV in June 1965, still wearing one of two NASA-issued Omega Speedmaster 105.003-63 chronograph on a long black velcro.

(Photo: NASA) #MoonwatchUniverse

#Aviator#Astronaut#Apollo#321#Speedmaster#chronograph#NASA#military#montres#MoonwatchUniverse#Gemini#velcro#Omega Bienne#Speedytuesday#uhren#horloges#sat#wrist watch#spaceflight#Zulu time

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Former NASA astronaut Jim McDivitt, who led Gemini and Apollo missions, dies at 93

Jim McDivitt, an astronaut who played a key role in making America's first spacewalk and moon landing possible, has died. He was 93.

Jim McDivitt, an astronaut who played a key role in making America’s first spacewalk and moon landing possible, has died. He was 93.

NASA confirmed his death to NPR on Monday, adding that he was surrounded by family and friends when he died on Thursday.

Known for being a courageous test pilot and dedicated leader, McDivitt commanded two of the most crucial flights in the early space race —…

View On WordPress

16 notes

·

View notes

Link

Substitute archive link (Unfortunately, the normal archiver didn’t capture the whole show, but a helpful listener did.)

Supplementary Shows

2022–10–25 As a counterpoint to the description from the Leonard book, last week, I read about a rocket launch at White Sands from the perspective of that eminent rocketeer, G Harry Stine : chapter 7, “Missile Away!”, from his 1957 book Rocket Power and Space Flight. Then, to round out the time, I read chapter 11, Space Travel and Our Lives.

2022–10–28 From Analog magazine, 1992 April, a resounding plea for the science fiction illustrator from Frank Kelly Freas (whom we have heard from before, also from Stine and Freas here), entitled The Story Between the Words, and an Alternate View column from G Harry Stine about “Intermittents”. Then, from the 1990 November number, the first part of Forging Planet–Stuff, an article about nucleosynthesis and its implications for planetary formation (and thus the kinds of stories one can credibly write), by Stephen L Gillett, PhD. He mentions another article, from 1983, which we may also want to read here.

1 note

·

View note

Link

6 min readPreparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater) On Christmas Day in 1968, the three-man Apollo 8 crew of Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders found a surprise in their food locker: a specially packed Christmas dinner wrapped in foil and decorated with red and green ribbons. Something as simple as a “home-cooked meal,” or as close as NASA could get for a spaceflight at the time, greatly improved the crew’s morale and appetite. More importantly, the meal marked a turning point in space food history. The prime crew of the Apollo 8 lunar orbit mission pose for a portrait next to the Apollo Mission Simulator at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC). Left to right, they are James A. Lovell Jr., command module pilot; William A. Anders, lunar module pilot; and Frank Borman, commander.NASA On their way to the Moon, the Apollo 8 crew was not very hungry. Food scientist Malcolm Smith later documented just how little the crew ate. Borman ate the least of the three, eating only 881 calories on day two, which concerned flight surgeon Chuck Berry. Most of the food, Borman later explained, was “unappetizing.” The crew ate few of the compressed, bite-sized items, and when they rehydrated their meals, the food took on the flavor of their wrappings instead of the actual food in the container. “If that doesn’t sound like a rousing endorsement, it isn’t,” he told viewers watching the Apollo 8 crew in space ahead of their surprise meal. As Anders demonstrated to the television audience how the astronauts prepared a meal and ate in space, Borman announced his wish, that folks back on Earth would “have better Christmas dinners” than the one the flight crew would be consuming that day.1 If that doesn’t sound like a rousing endorsement, it isn’t. Frank Borman Apollo 8 Astronaut Over the 1960s, there were many complaints about the food from astronauts and others working at the Manned Spacecraft Center (now NASA’s Johnson Space Center). After evaluating the food that the Apollo 8 crew would be consuming onboard their upcoming flight, Apollo 9 astronaut Jim McDivitt penciled a note to the food lab about his in-flight preferences. Using the back of the Apollo 8 crew menu, he directed them to decrease the number of compressed bite-sized items “to a bare minimum” and to include more meat and potato items. “I get awfully hungry,” he wrote, “and I’m afraid I’m going to starve to death on that menu.”2 In 1969, Rita Rapp, a physiologist who led the Apollo Food System team, asked Donald Arabian, head of the Mission Evaluation Room, to evaluate a four-day food supply used for the Apollo missions. Arabian identified himself as someone who “would eat almost anything. … you might say [I am] somewhat of a human garbage can.” But even he found the food lacked the flavor, aroma, appearance, texture, and taste he was accustomed to. At the end of his four-day assessment he concluded that “the pleasures of eating were lost to the point where interest in eating was essentially curtailed.”3 Food used on the Gemini-Titan IV flight. Packages include beef sandwich cubes, strawberry cereal cubes, dehydrated peaches, and dehydrated beef and gravy. A water gun on the Gemini spacecraft is used to reconstitute the dehydrated food and scissors are used to open the packaging.NASA Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman concurred with Arabian’s assessment of the Apollo food. The one item Borman enjoyed? It was the contents of the Christmas meal wrapped in ribbons: turkey and gravy. The Christmas dinner was so delicious that the crew contacted Houston to inform them of their good fortune. “It appears that we did a great injustice to the food people,” Lovell told capsule communicator (CAPCOM) Mike Collins. “Just after our TV show, Santa Claus brought us a TV dinner each; it was delicious. Turkey and gravy, cranberry sauce, grape punch; [it was] outstanding.” In response, Collins expressed delight in hearing the good news but shared that the flight control team was not as lucky. Instead, they were “eating cold coffee and baloney sandwiches.”4 The Apollo 8 Christmas menu included dehydrated grape drink, cranberry-applesauce, and coffee, as well as a wetpack containing turkey and gravy.U.S. Natick Soldier Systems Center Photographic Collection The Apollo 8 meal was a “breakthrough.” Until that mission, the food choices for Apollo crews were limited to freeze dried foods that required water to be added before they could be consumed, and ready-to-eat compressed foods formed into cubes. Most space food was highly processed. On this mission NASA introduced the “wetpack”: a thermostabilized package of turkey and gravy that retained its normal water content and could be eaten with a spoon. Astronauts had consumed thermostabilized pureed food on the Project Mercury missions in the early 1960s, but never chunks of meat like turkey. For the Project Gemini and Apollo 7 spaceflights, astronauts used their fingers to pop bite-sized cubes of food into their mouths and zero-G feeder tubes to consume rehydrated food. The inclusion of the wetpack for the Apollo 8 crew was years in the making. The U.S. Army Natick Labs in Massachusetts developed the packaging, and the U.S. Air Force conducted numerous parabolic flights to test eating from the package with a spoon.5 Smith called the meal a real “morale booster.” He noted several reasons for its appeal: the new packaging allowed the astronauts to see and smell the turkey and gravy; the meat’s texture and flavor were not altered by adding water from the spacecraft or the rehydration process; and finally, the crew did not have to go through the process of adding water, kneading the package, and then waiting to consume their meal. Smith concluded that the Christmas dinner demonstrated “the importance of the methods of presentation and serving of food.” Eating from a spoon instead of the zero-G feeder improved the inflight feeding experience, mimicking the way people eat on Earth: using utensils, not squirting pureed food out of a pouch into their mouths. Using a spoon also simplified eating and meal preparation. NASA added more wetpacks onboard Apollo 9, and the crew experimented eating other foods, including a rehydrated meal item, with the spoon.6 Malcolm Smith demonstrates eating space food.NASA Food was one of the few creature comforts the crew had on the Apollo 8 flight, and this meal demonstrated the psychological importance of being able to smell, taste, and see the turkey prior to consuming their meal, something that was lacking in the first four days of the flight. Seeing appetizing food triggers hunger and encourages eating. In other words, if food looks and smells good, then it must taste good. Little things like this improvement to the Apollo Food System made a huge difference to the crews who simply wanted some of the same eating experiences in orbit and on the Moon that they enjoyed on Earth. Footnotes [1] Apollo 8 Mission Commentary, Dec. 25, 1968, p. 543, https://historycollection.jsc.nasa.gov/JSCHistoryPortal/history/mission_trans/AS08_PAO.PDF; Apollo 8 Technical Debriefing, Jan. 2, 1969, 078-15, Apollo Series, University of Houston-Clear Lake, Houston, Texas (hereafter UHCL); Malcolm C. Smith to Director of Medical Research and Operations, “Nutrient consumption on Apollo VII and VIII,” Jan. 13, 1969, Rita Rapp Papers, Box 1, UHCL. [2] Jim McDivitt food evaluation form, n.d., Box 17, Rapp Papers, UHCL. [3] Donald Arabian to Rapp, “Evaluation of four-day food supply,” May 8, 1969, Box 17, Rapp Papers, UHCL. [4] Apollo 8 Mission Commentary, Dec. 25, 1968, p. 545. [5] Malcolm Smith, “The Apollo Food Program,” in Aerospace Food Technology, NASA SP-202 (Washington, DC: 1970), pp. 5–8; Whirlpool Corporation, “Space Food Systems: Mercury through Apollo,” Dec. 1970, Box 9, Rapp Papers, UHCL. [6] Smith, “The Apollo Food Program,” pp. 7–8; Smith to the Record, “Christmas Dinner for Apollo VIII,” Jan. 10, 1969, Box 1, Rapp Papers, UHCL; Smith et al, “Apollo Food Technology,” in Biomedical Results of Apollo, NASA SP-368 (Washington, DC: NASA, 1975), p. 456. About the AuthorJennifer Ross-NazzalNASA Human Spaceflight HistorianJennifer Ross-Nazzal is the NASA Human Spaceflight Historian. She is the author of Winning the West for Women: The Life of Suffragist Emma Smith DeVoe and Making Space for Women: Stories from Trailblazing Women of NASA's Johnson Space Center. Share Details Last Updated Dec 21, 2023 EditorMichele Ostovar Related TermsNASA HistoryApollo 8Frank BormanHumans in Space Explore More 12 min read Space Station 20th: Food on ISS Article 3 years ago 4 min read Apollo 8: Christmas at the Moon Article 4 years ago 4 min read To the Moon and Back: Apollo 8 and the Future of Lunar Exploration Article 5 years ago Keep Exploring Discover More Topics From NASA NASA History Humans In Space The Apollo Program Johnson Space Center History

0 notes

Text

AMAZING NEWS: 10/23/22

Steven H Silver commemorates Astronaut Jim McDivitt 1928 – 2022

From the Totally Mundane Department: Info for Authors – What Doctors Pack for Vacations

Ray Cuthbert brings us a video with Forest Ackerman, his father Chester Cuthbert and David Blair

Ralphie Returns!

Uncle Hugos is back and scheduling events!

Doug Ellis continues his series on the Things to Come newsletter art on Black Gate…

View On WordPress

0 notes