#indis

Text

What Comes Naturally

Fandom: The Silmarillion

Characters: Indis, Miriel

Summary: Two queens of the Noldor discuss motherhood.

Length: 2.9k

AO3 | Pillowfort | SWG

“What a trial motherhood was,” said Míriel in the understatement of several Ages, leaning back with a huff, so that she almost knocked Indis’ nose with the back of her head. “Not that you would know.”

“Not that I would know?” Indis echoed, her brows arched. However, she refrained from further remark, and Míriel elaborated. Since Míriel’s return, Indis had gathered that at times, Míriel would give explanation only if you kept quiet. (Other times, she would explain regardless of whether one wished it or not, but this was likely only with technical matters. On Míriel’s first day in the palace, Indis had received a three hour lecture on the function of various parts of a loom after fatefully inquiring how Míriel found her old tools.)

“Well,” said Míriel, and despite her dismissive tone, Indis felt something rawer in her voice now, facing away from Indis, than she had heard from her all that day, more even than when she’d had Indis’ hands between her legs. “Elfinesse the realm over praises your sweetness and care; I assumed that motherhood and nurturing came naturally to you.”

Indis resumed combing through Míriel’s sleek silver hair. Beyond the open windows, a dove whistled. The rest of the house was still and relaxed in the warmth of the sunlight as the day eased towards evening; perhaps the slowness of the day had led to this thoughtful (for so it was, even if Míriel feigned otherwise) conversation.

“Perhaps,” Indis allowed slowly. “Though ‘naturally’ does not mean ‘wholly without effort.’ The joy of it came naturally, certainly.” Míriel said nothing else, and Indis, with great restraint, held back from probing or trying to change the subject.

“For my part, I believe pulling teeth would have been a simpler and more rewarding task,” Míriel said at last into the silence of the bedroom.

“Surely it was not so terrible,” Indis objected, then cringed. Míriel snorted mirthlessly.

“Whatever Finwë told you of my efforts, certain I am that he was kinder to me than I deserve.”

Indis worked carefully through a small knot near the ends of Míriel’s hair. “You were ill, Míriel,” she said gently, at length. Míriel grunted.

“Yet still I was a terrible mother,” she said. “Even Fëanáro knew it, though he has since forgotten.” Indis opened her mouth, but Míriel silenced her before she could get in the air to disagree. “He always preferred Finwë,” she said. “Even as a babe in arms. How he wailed when I held him! And nothing could I do to calm him! At times I thought at the least he would eventually tire himself and then be content, but he seemed to have an endless reserve of energy for screaming, and the volume!” Míriel winced. “He could drive me to tears for want of a moment of quiet! So of course in the end I would give him over to Finwë, and it seemed at once he would be smiling and reaching out with his little hands and laughing! I cannot recall that he ever laughed for me. He must have, I suppose, but I…” Míriel trailed off, almost confused. Indis was not sure if her memories were muddled by virtue of her rebirth or the illness which preceded her death, or both.

“Finwë had a way with children.”

“I was told and told and told how naturally motherhood came, once the babe was born,” said Míriel, and Indis could picture the wrinkle of her flat nose. “Naturally! Not to me, but to Finwë, certainly. He seemed always to simply know what Fëanáro wanted, and if he did not, he would figure it out, or find some suitable substitute.” She shook her head.

“You would have come into it,” Indis insisted. “If you had had the time. You would have learned.”

“Perhaps. But if I must learn, then it was not natural.” Doubt shadowed her words. Again, she fell silent, and Indis forced herself not to fill it. Early evening light slanted through the windows, turning the mantle to gold, lighting up the dust motes floating around the bed curtains. Míriel lifted a hand as if to chase them with her touch; there were still times when she seemed amazed to be in the world again, to have physical sensations like touch and sight and sound (Indis, in the very new days, had found her by the fountain in the yard, weeping profusely over the sound the water made burbling up in the bowl of it, and often early she had touched Indis as if expecting her to dissipate beneath her fingertips.)

“I cannot say I was ever one who weathered failure gracefully,” Míriel said then, as Indis slid off the bed and went to the bottles and jars on her vanity. “I was failing at motherhood and I could see it, and I felt sure the baby and the rest of the city knew it too. And do you know? I resented him. I gave everything of myself to this child, and he would only smile for his father, and he made everyone whisper behind my back—or so I thought, I haven’t an idea if it was actually true—and even when he was quiet for me, he looked at me with these great accusing eyes as if to say he knew I was the worse parent.”

“Míriel…” Indis began uneasily, fingers lingering over the cosmetics. “Babies don’t…”

“I know, Indis, I know,” Míriel snapped. “But as you say, I was ill, and in my illness I was convinced this child whom I had given so much to bring into the world loved me not, nor would, and every day it seemed I could not escape my failures. I asked for him less and less; I felt the more I left to Finwë, the better for the child.

“Still he would come and see me, but even then I felt he disliked me. A-times I could hear him in the yard with his nursemaids, running and shouting and laughing as children do, but when he came to me, he had to play quietly, or not at all, for Mother’s head hurt, and Mother was tired, and Mother needed to rest. What joy is there for a child, sitting in a dark sick-room with a feeble shade of a woman who never knew how to be a mother?” Míriel lapsed into silence, scowling.

“You know he loved you,” Indis said quietly, returning to the bed with a small vial. She dabbed a bit of osmanthus oil from the vial onto her fingers to brush through Míriel’s hair. “You were his mother, and he loved you without thought for your condition.”

“What does a toddler understand of love? They know only safety and joy, or the absence of them. Love? What complexities of love could be grasped by such an infant? He knew that his father made him happy, and I did not; for him, what deeper considerations could exist?”

“I disagree,” Indis said. “I think he loved you even then. Perhaps he did not understand it, but he did.”

“Truly you think a babe can comprehend some notion of love?” Míriel asked, twisting around to look in skeptical astonishment at Indis.

“I do,” she said firmly. “Truly you believe they cannot?”

“A child who can barely string together a sentence, know love? Next you shall tell me mice and horses know it!”

“Must one be able to articulate the feeling to feel it?” Indis asked.

“I believe one must be able to understand it!”

“I disagree,” was all Indis said.

Míriel shook her head. “Yours is a gentle spirit I think,” she said. “Better not to comprehend an absence of love. I see why Finwë chose you.”

“Gentle, perhaps, but I should think not naïve,” Indis replied with a hint of an edge. “I do not speak out of blind hope, Míriel.”

Míriel regarded her a moment, and then said: “No, I did not think so. I would not accuse you of that. Perhaps it is only that I have grown cynical. No—perhaps that I always was.”

There were things Indis could have said then—about the vain effort of cynicism to protect a weary heart, about Míriel’s struggles, about the necessity of not closing oneself off to feeling—but instead she just took Míriel’s hand and squeezed it.

“I will not say I have never felt it, for that would be a lie. But you were telling me of Fëanáro’s infancy,” she said, and Míriel nodded. Still she was quiet a moment, and Indis thought the interruption would be the end of Míriel’s sharing, but then she continued.

“Yes…the more my illness took me, the less reason girded my thoughts, as you can see. As my weariness grew, I convinced myself that I was doing him a favor; that he would, truthfully, be better off without me. One can always convince oneself that one’s desired course of action is also, coincidentally, the best for everyone else, isn’t it so?”

Indis bit her lip against the desire to interject that that it could never have been that Fëanor or anyone else would have been better off if Míriel were dead.

“What a little fool he was, too,” Míriel went on crabbily. “To think he had the fortune of a mother such as yourself walking into his life, and he pushed you away for want of me! I should pinch him if I could. The real tragedy would have been if you and I had traded places!”

“I think you are too hard—”

“All of that rather makes it sound like I cared not for him, doesn’t it?” Míriel let out another long sigh. “It isn’t so. He was the flesh of my flesh, how could I not love him? Or at least…in the beginning. At the end, I do not believe I loved anything. I had not the capacity any longer.” Indis was neither combing nor braiding, simply running her hands through Míriel’s hair in hopes of soothing her. “But there it is, you see? I think no matter how ill you were, Indis, you could not watch your children sobbing at your bedside, could not hear them begging for you to come home, to be a mother, and feel nothing.”

“I do not think you felt nothing,” said Indis quietly. Míriel’s shoulders tensed.

“Was it not near enough? Nothing he said, nothing Finwë said, would change my course. I broke his heart, and I knew I was going to do it. And out of sheer stubbornness, I refused to return once I had done it.”

“You were—”

“Yes, yes, I was unwell,” Míriel said forcefully. “And yet, I was myself still. I was not deprived of my faculties. I was aware of the consequences of my actions.”

“Such knowledge may become subordinated to extended pain and discomfort,” said Indis. “We are, after all, still physical beings. True thought is difficult when one’s mind is focused on the struggles of the body.” When Míriel said nothing, Indis added: “I know not that I could have done otherwise in your place. I have never felt as you did then.”

“I feel quite assured you would have borne it with more grace.” Míriel’s tone was breezy, and Indis could not discern if there was something heavier beneath it or not.

“I know that you bore it a long time,” said Indis, beginning to weave Míriel’s hair into a set of braids. “I tend to doubt very much I could have managed so long.”

Míriel leaned back slightly into Indis’ touch, relaxing a little. “It felt like a long time,” she murmured. “Stars, it felt like such a long time. It was only a few years. But it felt so terribly, terribly long.”

“I think ‘tis a credit to your love,” said Indis, “for Finwë and for Fëanáro, that you endured so long as you did.”

Míriel said nothing, and Indis worked the second braid down to the tie. She thought back to what Míriel had said earlier. It had never occurred to her, in all her morose anxiety that she would never live up to the exalted former queen of the Noldor, that there was anything Míriel might have felt similarly about, looking at Indis.

“I know you would have been a good mother to Fëanáro, if he had permitted it,” Míriel said at last. She twisted around on the bed to look at Indis. “And I am grateful, for what you did do.”

“It was not much,” Indis demurred. Fëanor had not allowed it to be much, and at some point, Indis had given it up as a lost cause.

“I fault you not for that,” Míriel said with a wry twist of her mouth. “When I died, I had hopes that Fëanáro would turn out to be like his father. Everyone likes Finwë. How could anyone not? In fact, I believe he was sometimes overconcerned with how well he was liked. And Fëanáro looked so like him, even as a child! Unfortunately, it seems he took after myself, and so I have great pity for you.”

Indis could not help but giggle at this, try as she might.

“I see you trying not to laugh,” said Míriel. “But you ought; ‘tis true. Finwë was liked and I was a bitch.”

“You were liked!” Indis exclaimed. “Even still, you have scant idea how the Noldor lamented your absence.”

“Mm. Liked, perhaps, but likeable? No, that was never me. If anything, I was liked in spite of myself. I never did understand why Finwë chose me.”

“He was amazed by you,” said Indis with a smile. It was good, when they could speak comfortably of their pasts this way, without rancor or injury. “That never changed. Nor do I disagree with him.” Míriel’s lips curved into a smile as well, softly fond, and Indis found herself saying: “Do you remember how he would smile, that one particular way, where you could just imagine what he might have looked like as a child?”

Míriel’s smile grew. “Yes, I know the look,” she said, flashing teeth. “Ah, but how he charmed me with that! He was a beautiful thing, wasn’t he?”

“I will tell you,” said Indis, “I saw it very rarely, but once or twice, I have seen Fëanáro smile that way.”

Míriel’s eyes grew distant, as if she were drawn into a dream, but her smile remained, close-lipped once more. There was such a silent ache about her that Indis could not resist throwing her arms around Míriel’s shoulders to embrace her from behind, squeezing her tightly as if to give physical reassurance that she was not alone. Míriel’s loose robe slipped down her shoulders at Indis’ touch.

“But he was clever like you,” Indis whispered to her. There had been a time when she could not have spoken of Fëanor this way, when her anger and bitterness against him overbore any of the sympathy she had harbored for him in his youth. Half of her children and all her grandchildren he had stolen from her, and never had he missed a chance to spit in her face if he could. Yet there had been a time too when she had seen the better in him, and empathized with his pain, and there was almost relief, in speaking of him with Míriel, in purging the acidity of her wrath. It did little good, she reminded herself, to dwell perpetually in anger, even if the object of it would walk no more among them. Nothing in her garden grew of her anger. “I saw it in the work you left behind. Your minds ran the same paths.”

“Pity the boy,” said Míriel ruefully. “And his father too!”

“I think neither of them would have had it any other way.”

Míriel put a hand over Indis’, and rubbed the back of Indis’ hand, slowly returning from that dreamy place where she at times withdrew to, as if her mind were still making sense of how much had changed since she last lived in truth. It was some moments before she spoke again.

“I understand he was difficult for you,” said Míriel. “And for that I apologize...I am still…still learning of the full extent of all that transpired…” Míriel’s voice had grown thicker, and Indis could catch a glimpse of the grief that the queen tried so doggedly to shield from view. “I spoke again with your grandson several days past; he told me a little more of the fortunes of the Noldor in Middle-earth…” A place they never would have been but for Fëanor’s rebellion. Indis knew that Finrod would be cautious in what he shared, but Míriel was sharp enough to fill in many gaps. She knew how much ruin had come of Fëanor’s actions, if she did not yet know every detail of it.

“And I have spoken a short while with his wife.” Indis had hoped that Míriel and Nerdanel might share something of a grief the rest of the Noldor were not keen in hearing of, but as neither of them was particularly inclined to spill their hearts to a stranger, she could not say yet if introducing them had done any good. “But ‘twas you that knew him in his youth. Could you—would you—tell me something else of him, of my son?”

“Of course,” said Indis, loosening her hold on Míriel. She eased back down onto the mattress and sat beside Míriel so that she could still hold her hand. “What would you like to know?”

“Anything,” said Míriel. “Everything.”

#miriel#indis#mindis#the silmarillion#tolkien tag#fanfiction#tolkien fanfiction#rocky writes#sapphictolkien#technically

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

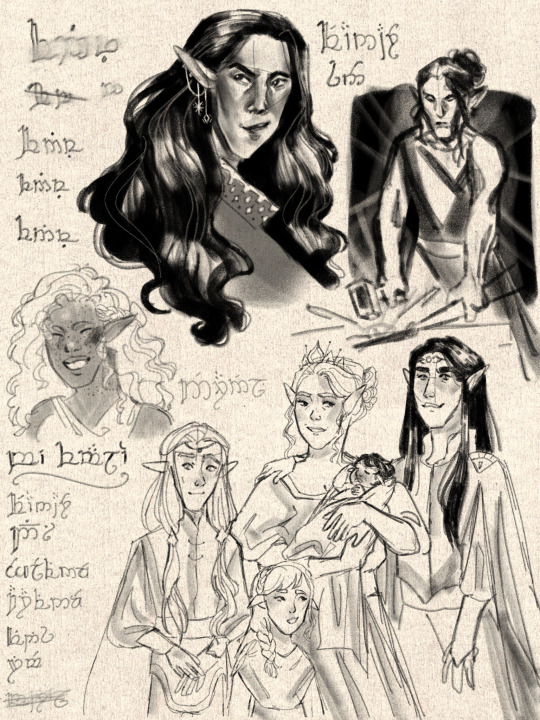

Queen Indis🫡

#the silmarillion#silm#tolkien#indis#my queen#do not mistreat#i gave her a sword#sketch#fanart#illustration#art

744 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marriage of Finwë

...and the thread of destiny is spun ever on.

aka Fëanaro is not impressed :) Not-so-transparent ghost Miriel under the cut

#my art#feanor#finwe#house of finwe#indis#tolkien#silmarillion#miriel#Míriel Þerindë#tapestry of time#this took me an embarrassing long time#but hey at least I have now a Finwe and an Indis design#weeeh

699 notes

·

View notes

Text

House of Finwë ~

Finwë - Miriel - Indis - Findis - Lalwen

// prints!

fëanorians: 1 - 2 - 3

nolofinwëans: 1 - 2 - 3

arafinwëans: 1 - 2 - 3

#finwe#miriel#indis#findis#lalwen#irime#feanor#fingolfin#finarfin#noldor#elves#tolkien#silm#silm fanart#silmarillion#lotr#lord of the rings#portraits#digital art#middle earth#jrr tolkien#silm art

284 notes

·

View notes

Text

love is love silmaril is silmaril

#silmart#beren and luthien#the silmarillion#russingon#beren erchamion#luthien tinuviel#maedhros#fingon#miriel#indis#morgoth#in that order.#ok i'm done working on this i'm going to send it out before i think too much about it. have fun besties.#tolkien#my art

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

To them the rage, to us the pain

#indis#nerdanel#the silmarillion#the silmarillion art#my art#forestials art#mmmm indis gets it#agonisingly so

558 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please read this Morgoth's Ring quote with me cuz this is PEAK Fëanor and Fingolfin angst potential:

[[This is Finwë talking to the Valar about Indis]] "But Indis parted from me without death. I had not seen her for many years, and when the Marrer smote me I was alone. She hath dear children to comfort her, and her love, I deem, is now most for Ingoldo. His father she may miss; but not the father of Fëanáro!"

Those familiar with only the Shibboleth's list of quenya names might assume that this is referencing Finarfin, but no. At this point in the story, Ingoldo was Fingolfin's mother-name. This quote implies that, according to Finwë's observations, Fingolfin was Indis's favorite child.

SO IMAGINE; Fëanor, who loves his mother so dearly and so desperately, but never knew her, and therefore never felt her love in return, looking at Fingolfin, who gets the favoritism and motherly love that he craves yet never got. Imagine how jealous and furious that might make him, especially since he hates Indis so much. I can't help but wonder if Fingolfin's being his mother's pride and joy was one of the reasons why Fëanor seemed to hate him the most of his half-siblings.

331 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anaire: “So how’s life with a baby?”

Nerdanel: “Exhausting. I didn't know that it was possible for someone to cry this much.”

Indis: “Oh, I’m sure he’ll grow out of it soon.”

Nerdanel: “Oh no, no, no, no. The baby’s an angel, he’s no trouble at all.”

Earwen: “...But you just said-?”

Feanor, holding baby Maitimo and crying: “Nerdanel, I love him so much!”

372 notes

·

View notes

Text

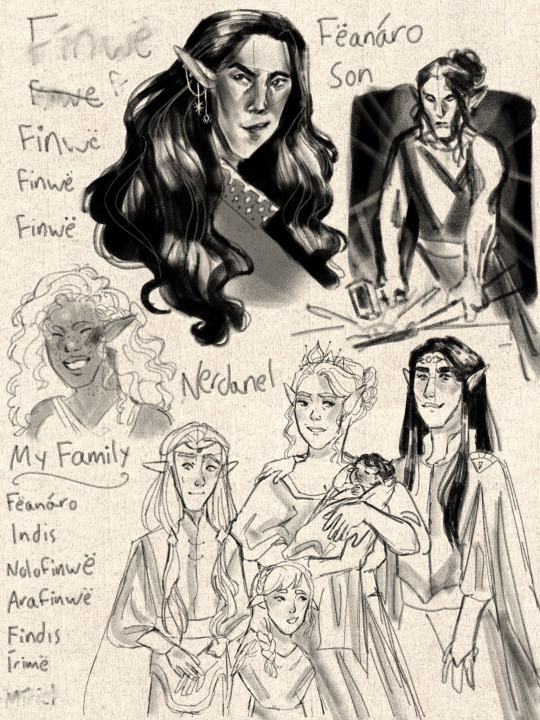

Here’s my artwork for @silmarillionepistolary day 4, love and creation!

More time has passed, and Finwë still loves his art, his people, and his growing family. His eldest son, Fëanáro (shown on the top left and right), has grown into an ambitious and genius adult. He is always creating and inventing new things - even a written language! Finwë has spent much time learning the script (a few failed attempts are shown in the top left corner), but he is immensely proud of his son (and his wife, Nerdanel, pictured below him).

Finwë’s ‘other family’, so called by Fëanáro (who doesn’t get along with them at all), has grown over the last several years. Indis is a ray of sunshine in his life, and as strong a woman as she is a Queen - she has borne four children and remains as joyful and sturdy as ever. Nolofinwë is the eldest, followed by Arafinwë, then his two daughters Findis and Írimë. Finwë adores children, and would love to always have them near him forever. (Though his own are swiftly growing up, Nerdanel is already pregnant with her first child, which is very excited about).

Still, though his first wife makes no more appearances in his sketches … she always lingers in the back of his mind, a phantom he could not erase even if he wanted to. And he doesn’t want to, no matter how much guilt he feels about pining over Míriel when his living wife is ever beside him.

Tengwar translations (the language is English transcribed into Tengwar):

#lord of the rings#art#my art#the silmarillion#finwe's sketchbook#finwe#house of finwe#silmarillion epistolary#indis#Fëanorian#nerd#fingolfin#finarfin#findis#irime lalwen#fandom event

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indis appreciation post!

Disclaimer: All the canon info is taken from Morgoth's Ring and Peoples of Middle Earth. Also, this isn't a character analysis/meta. It's just a list of stuff I love (plus some headcanons) about one of my favorite characters in the legendarium.

1. She's athletic and outdoorsy. We're told that Indis is "exceedingly swift of foot" and that "she walked often alone in the fields and friths of the Valar, turning her thought to things that grow untended." When Finwe sees her, she's chilling on a mountainside. I love that she's associated with nature, specifically the wilderness. She parallels Feanor in her exploration of Aman and interest in the imperfect. Also, this is purely self-indulgent but ever since reading HoME for the first time, I've pictured Indis as tall and broad, and muscular beneath a layer of fat.

2. She doesn't let her unrequited love affect her life. "There was ever light and mirth about her." She's not the pining, languishing princess stereotype. She goes on. She doesn't let it make her bitter or depressed, and she is so restrained that only Mandos and possibly Ingwe are aware of her feelings.

3. Part of her attraction to Finwe is intellectual. In HoME we're told that his "mastery of words delighted her." Considering that Indis is also a poet/composer ("wove words into song") and that the Vanyar enjoy linguistics, it makes sense. It's also just really cute.

4. She's politically minded. Her reasoning for pronouncing 's' instead of 'th' is: "I have joined the Noldor, and I will speak as they do." This is the right thing to do to gain the respect of the Noldor and their acceptance of her authority. I also think she makes a statement with Fingolfin and Finarfin's mother-names. Arakano ("high chieftain") and Ingoldo ("the Noldo, eminent among the kindred") are not only powerful, prophetic names, they're also strikingly similar to Ingwe ("chief of chieftains") who is the High King not just of the Vanyar, but all Eldar. What a power move.

5. She's able to balance her own culture with the culture she marries into. Indis integrates into Noldorin society easily while remaining Vanyarin at her core, as is evidenced by Finwe saying that "above all her heart now yearns for the halls of Ingwe and the peace of the Vanyar." Her sons also respect and are proud of their mixed heritage; Finarfin "loved the Vanyar, his mother's people" and is said to be like them (as are Finrod and Galadriel), and Fingolfin's daughter-in-law is Vanyarin (plus the Nolofinweans have a special connection to Manwe).

6. She gets an awesome prophecy about her line. "But I say unto you that the children of Indis shall also be great, and the Tale of Arda more glorious because of their coming. And from them shall spring things so fair that no tears shall dim their beauty; in whose being the Valar, and the Kindreds both of Elves and of Men that are to come shall all have part, and in whose deeds they shall rejoice. So that, long hence when all that here is, and seemeth yet fair and impregnable, shall nonetheless have faded and passed away, the Light of Aman shall not wholly cease among the free peoples of Arda until the end." Fuck yeah.

7. Her name means "valiant woman." This is the only definition given in Morgoth's Ring, I believe. I highly prefer it over the "bride" meaning because it's a badass name and is similar to Artanis ("noble woman") and Astaldo ("the valiant"). A headcanon that I'm particularly attached to is that Indis's mother-name is Indome, meaning "will of Eru."

8. She's popular with most of the Noldor. We're told that "Finwe, King of the Noldor, wedded Indis, sister of Ingwe; and the Vanyar and Noldor for the most part rejoiced." The majority of the Noldor also follow Fingolfin and Finarfin instead of Feanor.

9. She's friends with Nerdanel. HoME states that Nerdanel went to "abide with Indis, whom she had ever esteemed."

10. She gets pissed off at Finwe when he sides with Feanor. So much so that he thinks she won't want to see him if he's re-embodied. I know this is from his perspective but I'm inclined to agree. [However, this is still very presumptive of him, and his comment that "Indis parted from me without death" is super shitty. Eugh.]

11. She's close to her kids. Finarfin takes after her, Fingolfin passes on the name she gave him, Findis lives with her, Lalwen goes by the name she gave her. Finwe also says that "she hath dear children to comfort her."

So there we have it! What little info we get about Indis is pretty awesome. And this is just a list; I could write a whole essay on her fortitude and unconventionality and my numerous headcanons about her.

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conditions sound ripe for every single one of Finwë's children and grandchildren to have a complex about never being enough and needing to prove their right to exist.

"...many saw the effect of this breach within the house of Finwë, judging that if Finwë had endured his loss and been content with the fathering of his mighty son, the courses of Fëanor would have been otherwise, and great evil might have been prevented...But the children of Indis were great and glorious and their children also; and if they had not lived the history of the Elder would have been diminished" (Ch 6, The Silmarillion).

Yes, this sounds like the narrator's justification of Indis' marriage and her descendants' right to freaking exist but it is justified on account of their actions, not their personhood.

With this quote it's most obviously Indis' descendants, but this applies to Feanor too: feeling like he has to be the best and the greatest to make up for "causing" his mother's death.

If such a view was prevalent--what if they all felt like they had something to prove; what if they all felt like they needed to make their mark on the world to prove that they had a right to exist?

What if they all believed that they had to do something great, something more epic than anyone could've imagined, to make their existence worthwhile, to balance out the damage that their existence created?

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

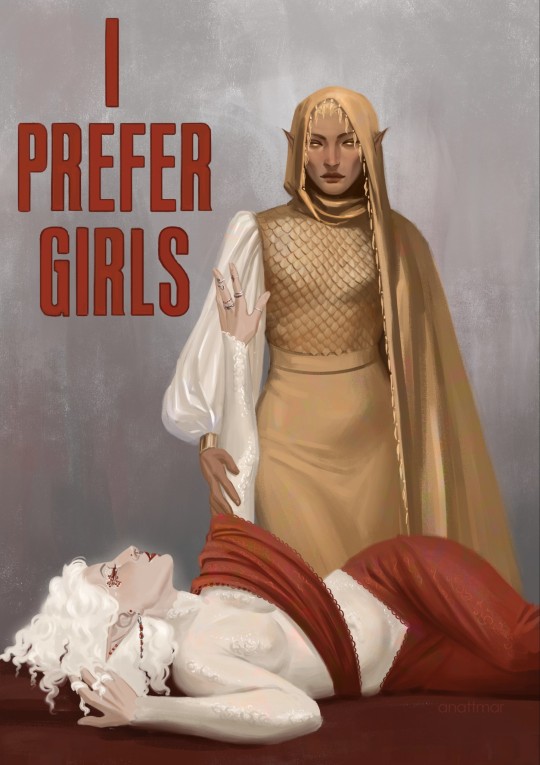

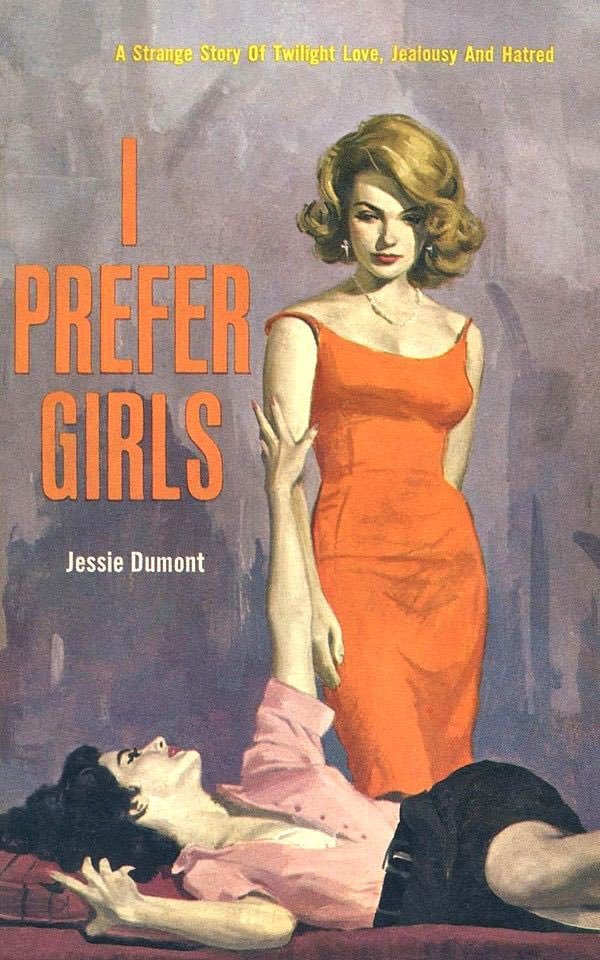

no but that's literally them

[artist of the original illustration is Robert Maguire]

#the silmarillion#silm#tolkien#indis#míriel#miriel therinde#indis/míriel#finwë is hyping them up#redraw#fanart#illustration#art

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

concept i've been thinking about lately: feanor writes all his notes in conlangs. so no one else can understand them, of course. except sometimes, he can't understand them either. this is the real reason why the silmarils were a one time thing.

#imagine: ñolo tries to sneak into feanaro's office and get his notes to figure out what hes working on and he just#cant understand any of it#iconic#tell me feanor wouldnt do his#and he would keep a journal where he talked shit about his brothers and indis also in conlangs#and eventually ñolo finds the key/notes for one of them and learns it#and just casually greets 'naro in it one day#and feanor's just like 👁️👄👁️#i love them your honor#feanor#feanaro#sons of finwe#nolofinwe#arafinwe#fingolfin#finarfin#indis#miriel#finwe#silm#silmarillion#tolkien#valinor#silmarils

250 notes

·

View notes

Note

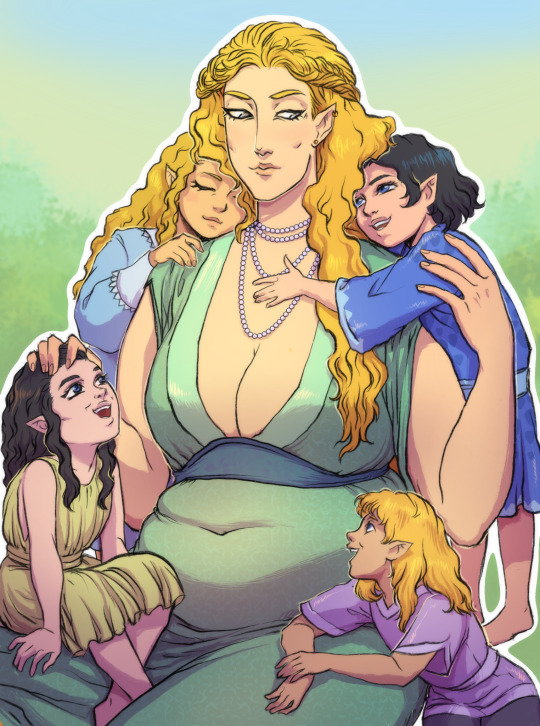

Can I request chubby Indis?

Certainty! Here is the golden mama 😌✨ and her smol beans!

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine if Fëanor and Indis actually got along really well.

I know that most people perceive that he hated her because she 'replaced' Míriel, but just imagine that they somehow managed to talk everything out and then get along and maybe even become friends.

But they still make a joke of pretending to hate each other when other people are around. And in private they make up insults to throw at each other when they're at the next family party, out of fun.

However, they make the insults so absurd that they make the others laugh. The two try to heal their somewhat broken family with that.

I think Finarfin would notice it first. But Fingolfin would also realize it, because Fëanor started to call him 'little brother' instead of all the 'nice' nicknames that he had normally for him.

▪︎ ▪︎ ▪︎

Finwë: Can you two at least pretend to get along?

Fëanor & Indis, who pretend to not get along: ...

138 notes

·

View notes