#he just got converted into a splendid red engine

Text

so I was trying to figure out why this one dude held 5% of the Iraq Petroleum Company, right alongside Standard Oil of New Jersey (Exxon) and Socony-Vacuum (Mobil), Compagnie Française des Petroles (Total), Anglo-Iranian (British Petroleum), and Shell, and it turns out to have been this very strange and wealthy Armenian guy

I’m just going to quote from Daniel Yergin’s The Prize

Calouste Gulbenkian was the second generation of his family in the oil business. He was the son of a wealthy Armenian oil man and banker, who had built his fortune as an importer of Russian kerosene into the Ottoman Empire, and who had been rewarded by the Sultan with the governorship of a Black Sea port. The family actually lived in Constantinople, and there occurred Calouste's first recorded financial transaction. Given, at age seven, a Turkish silver piece, the boy took it off to the bazaar, not to buy a sticky candy as might have been expected, but to exchange it for an antique coin. (Later in life he would create one of the world's great collections of gold coins, and he took special pleasure in acquiring J. P. Morgan's superb collection of Greek gold coins.) Unpopular as a schoolboy—throughout his life there was never to be any great love lost between him and the rest of humanity—the young Calouste often spent his after- school hours in the bazaar, listening to deals being made, sometimes making small ones himself, imbibing the arts of Oriental negotiation.

... A professor at King's suggested that the obviously talented young Armenian student go off to France for graduate studies in physics, but his father overruled the idea. Such a notion, he said, was "academic nonsense." Instead, his father sent Calouste to Baku, from which the family's fortunes had, in large part, derived. The young man was fascinated by the oil industry that he was seeing for the first time. He was also drenched by a gusher, but the oil being "fine and consistent," he did not find the experience unpleasant. Though pledging to return, he never bothered to visit oil country again.

Gulbenkian wrote a series of highly regarded articles on Russian oil, which appeared in a leading French magazine in 1889, and he turned the articles into a prestigiously published book in 1891—making himself a world oil expert by the time he was twenty-one. Almost immediately after, two officials of the Turkish Sultan asked him to investigate oil possibilities in Mesopotamia. He did not visit that area—he never did—but he put together a competent report based on the writings of others, as well as on talks with German railway engineers. The region, he said, had very great petroleum potential. The Turkish officials were persuaded. So was he. Thus began Calouste Gulbenkian's lifelong devotion to Mesopotamian oil, to which he would apply himself with extraordinary dedication and tenacity over six decades.

In Constantinople, Gulbenkian tried several commercial ventures, including selling carpets, none of them particularly successful. But he did master the arts of the bazaar—trading and dealing, intrigue, baksheesh, and the acquisition of information that could be put to advantageous use. He also developed his lifelong passion for hard work, his capacity for vision, and his great skills as a negotiator. Whenever he could, he would control a situation. But when he could not, he would follow an old Arab proverb that he liked to quote, "The hand you dare not bite, kiss it." In those early business years in Constantinople, he also cultivated his patience and perseverance, which some said were his greatest assets. He was not prone to budge. "It would have been easier," someone later said, "to squeeze granite than Mr. Gulbenkian."

Gulbenkian possessed one other quality. He was totally and completely untrusting. "I have never known anybody so suspicious," said Sir Kenneth Clark, the art critic and director of the National Gallery in London who helped Gulbenkian in later years on his art collection. "I've never met anybody who went to such extremes. He always had people spying for him." He would have two or three different experts appraise a piece of art before he bought it. Indeed, as he got older, Gulbenkian became obsessed with bettering a grandfather who had lived to the age of 106 and, to that end, employed two different sets of doctors so he could check one against the other.

he ended his life in litigation to prevent Standard Oil and Socony from participating in Saudi Aramco

But what, in essence, did Gulbenkian want? Some suspected that he actually aimed to get a share of Aramco. That was out of the question. Ibn Saud would never allow it. To a director of Socony, Gulbenkian offered a simple explanation of his objective. He could not respect himself unless he "drove as good a bargain as possible." In other words, he wanted as much as he could get. To another American, not an oil man at all, but one who shared his love of art, Gulbenkian could explain still more. He had made so much money that more money, in itself, did not count for very much. He thought of himself in the same terms he had used to Walter Teagle two decades before—as an architect, even as an artist, creating beautiful structures, balancing interests, harmonizing economic forces. That was what gave him his joy, he said. The artworks he had collected over his lifetime had come to compose the greatest collection ever assembled by a single person in modern times. He called them his "children," and seemed to care more for them than for his actual son. But his masterpiece, the greatest achievement of his life, was the Iraq Petroleum Company. To him, it was as architecturally designed, as faultlessly composed, as Raphael's The School of Athens. And if he was Raphael, Gulbenkian made clear, he regarded the executives of Jersey and Socony in much the same company as Giroloma Genga, a third-rate, mediocre, obscure imitator of the masters of the Renaissance.

you have to love the final agreement, too

Thus was negotiated the Group Agreement of November 1948, which reconstituted the Iraq Petroleum Company. What Gulbenkian got, in addition to higher overall production and other advantages, was an extra allocation of oil. Mr. Five Percent was no more; he was now something greater. The agreements themselves were "monuments of complexity." An Anglo-Iranian executive (and later a chairman of the company) declared, "We have now succeeded in making the Agreement completely unintelligible to anybody." But there was an advantage to such complexity, for, as one of Gulbenkian's lawyers put it, "No one will ever be able to litigate about these documents because no one will be able to understand them."

Once the granite obduracy of Calouste Gulbenkian had been overcome and the new Group Agreement for the Iraq Petroleum Company had been signed, the Red Line Agreement was no more, and the legal threat to Jersey's and Socony's participation in Aramco was removed. It had been a long, tortured struggle by which the two companies won their entrée to Saudi Arabia. "If you laid all the conversations that went into this deal end to end," said one participant, "they would reach to the moon." In December 1948, two and a half years after the deal had first been discussed, the Jersey and Socony loans could be converted into payments, and the Aramco merger could finally be completed. A new corporate entity, more commensurate with Saudi re serves, had come into existence. With the deal done, Aramco was owned by Jersey and Socony, as well as Socal and Texaco. And it was 100 percent American.

For his part, Gulbenkian had once again succeeded in preserving his exquisite creation, the Iraq Petroleum Company, as well as his position in it, against the combined might of international oil. His last display of artistry was ultimately to earn hundreds of millions of dollars more for the Gulbenkian interests. Gulbenkian himself lived on for another six years in Lisbon, occupying himself by ceaselessly arguing with his IPC partners and by writing and rewriting his will. When seven years later, in 1955, he died at age eighty-five, he left behind three enduring legacies: a vast fortune, a splendid art collection and, most fittingly of all, endless litigation over his will and the terms of his estate.

I like this guy

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://www.injectionmouldchina.com/memories-of-bristols-grand-spa-ballroom/

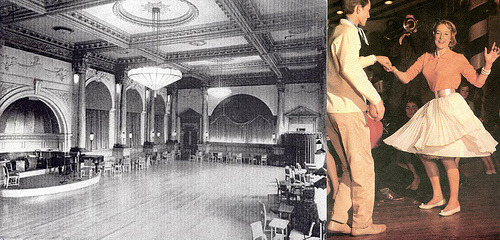

Memories of Bristol's Grand Spa Ballroom

Some cool plastic molded part images:

Memories of Bristol’s Grand Spa Ballroom

Image by brizzle born and bred

Dancing Through Time

The Spa in Clifton opened to great acclaim but is now derelict

MANY rising stars of the 1950s, such as Shirley Bassey, Petula Clark and Peter Sellers, appeared at Clifton’s Grand Spa Ballroom. And thousands of Bristolians enjoyed the sounds of big bands here, at a dance hall which has been locked up for more than three decades.

But this was no ordinary dance hall. Situated at the foot of a steep staircase leading off Sion Hill, it had originally been built as the Pump Room of the Clifton Grand Spa and Hydro, an upmarket hotel which opened near the suspension bridge in 1894.

Often entertainment was laid on here for the personnel of Navy ships, such as at the time of the visit of various warships in 1898. It was described as a hall of admirable proportions, 100 feet by 57 feet, ceiling height 27 feet, elegant and light with an uninterrupted view from the windows of Leigh Woods, the Suspension Bridge and Nightingale Valley. In the centre was a fountain of white marble with a raised fluted basin. All doors, window frames, panelling and floor were made of oak.

In 1898 it was reported that the Pump Room, being part of the Spa and Hydro, had not only been redecorated but also a passenger elevator had been installed to give access to all the floors of the hotel.

This had been financed by wealthy publisher, entrepreneur and one-time MP Sir George Newnes, who was also the promoter of the adjoining Clifton Rocks Railway. Seven hundred influential Bristolians were invited to the opening dinner. After a sumptuous meal followed by the obligatory speeches, they were entertained by the Band of the Life Guards and singing from Madame Strathearn.

The directors of the Clifton Grand Spa and Hydro boasted that its grand Pump Room was the “most highly decorated and finest in the kingdom”.

However, by 1922, the popularity of the Pump Room and Spa had waned and it was turned into a cinema. Six years later, it became a ballroom, and by the 1950s and 1960s it was one of Bristol’s most popular dance halls.

Long-serving entertainments director Reg Williams, who had his own top band at the Park Row Coliseum in the 1930s, developed a cabaret policy featuring many youngsters destined to be stars.

The 15-piece Grand Spa band was the first to introduce Latin American rhythms to the city.

The musicians played from a bandstand in an alcove, a place from which visitors once took the spa waters pumped up from 250ft below, through the rocks from Hotwells. Dennis Mann, who ran the Grand Spa Orchestra for 10 years from 1960, remembers the ballroom with much affection.

“It was such a wonderful ballroom,” he recalled.

“As a musician, I’d toured all over the country, but this was something different.”

“People danced between ornate pillars. At the bottom of the staircase there were marble

steps leading into the ballroom.

“I remember that the women were well-dressed. Up north, they danced wearing headscarves, but at the Grand Spa they were beautifully dressed. And the men wore suits

and ties.”

The singer for Dennis’s band was his wife, the late Shirley Jackson.

“We were working in different parts of the country,” he recalled, “and I thought the only way we could see each other was by forming my own band, with Shirley in the nine-piece set up. We broadcast for the BBC’s old Light Programme from the Spa, and we once played with the singer Janie Marden for a live radio outside broadcast.”

“The ballroom was open six nights a week. We called Thursdays ‘reps night’.

That’s when firms’ representatives who were in Bristol for the week turned up for a night out before going back home the next day,” said Dennis.

“Friday nights was always kept for private functions. We used to play at lots of dances for firms like Rolls-Royce, police balls and press balls. Old Bristol firms, like the engineers Strachan and Henshaw, used to have their dances at the Spa.

“We used to get 800 people and more into the ballroom. On New Year’s Eve, it would probably be nearer 1,000. I remember that during the interval the band would jump into their cars and go around to the nearby Coronation Tap for a couple of pints of cider.”

After Dennis left the Grand Spa, he joined the QE2 as bandmaster for six months.

“I was on board when the SAS were winched onto the ship from a helicopter during a bomb scare,” he recalled.

The Grand Spa sparked countless romances, as couples danced between the splendid marble pillars. A popular feature was a machine in the ladies’ toilets, girls who put in sixpence got a spray of perfume.

Delphine Lydall, who lives opposite the old ballroom, remembered: “It was very ornate, very Victorian. I met my husband there on a Monday night. Monday was the under-21 club night. It was all run very properly, and it finished at 10.30pm.”

There were blue and green upholstered wooden-framed chairs, and built in red leather settees that lined the room. The huge 1920s lights were retained, but were dimmed, and used in combination with wrought-iron lantern holders, screwed into the oak plinths of the marble columns to make the place more intimate. The raised platform on the North West side that was installed in the 1922 cinema, covering one fifth of the total floor area, was retained. A second new raised platform was introduced in the alcove, where the stone fountain once stood, which served as a jazz band stand. At the time, it was described as a three-level rostrum with a shell-back for the orchestra. The Music Gallery was turned into a buffet and additional bar for refreshments, the main bar was off the hotel end of the ballroom (underneath the marble staircase).

In the 1960s and 70s, the hotel ballroom was converted to a disco. The original retiring room between the Clifton Rocks Railway and the disco had been fitted out as a make-shift kitchen. Against one wall was a laminated worktop lined with a few 1970s floral wall tiles, with a kettle and a couple of hot rings to make teas, coffees and soup. The Music Gallery was bricked up, and plastic padding put between the bricks and the moulded plaster capitals of the pilasters on either side of the archway, to protect them, in the hope that one day it would be restored. By the middle of the 1970s, all the original decoration had been painted black or dark green and covered by a suspended hessian ceiling; wooden frames were constructed round the marble columns, which were covered in hessian, and lights were replaced with disco lighting.

The Grand Spa changed its name to the Avon Gorge Hotel some 30 years ago, and ever since then the ballroom has been standing derelict. Robert Peel, the hotel’s new owner, has submitted a £10 million scheme to redevelop the whole site, including the terraces spilling down the cliff.

He would like to restore the ballroom, but says this can only be done if permission is granted for the whole complex.

“To restore it would be a great feat, but restoring it on its own would not be financially economical,” he said.

The Grand Spa wasn’t the only post-war dance venue in the city. The Mecca organisation bought the small ballroom known as The Glen, situated in an old quarry off Durdham Down. This became so popular that they built a new one, The Locarno. The site is now the Bupa hospital car park.

The Victoria Rooms was another hugely popular dance hall. The big band of Ken Lewis, who later became a full-time official of the Musicians’ Union in Bristol, often played there.

A couple of hundred yards down Queens Road, opposite the university’s Wills Memorial Building, was the Berkeley Cafe, owned by the Cadena group, which advertised itself as the “largest and most up-to-date cafe in Bristol”.

With seating for 1,200 people, the Berkeley Orchestra played three sessions each day.

The popular “tea dances” held in the cafe’s Queen’s Hall every Wednesday, Thursday and Saturday afternoon attracted crowds of dancers from all over. The building, which retains its original name, is now a pub.

Clem Gardiner and Arthur Parkman, each with their own bands and their own following, were familiar faces at the Grand Hotel in Broad Street and the Royal Hotel on College Green.

Across the river, band leader Eric Winstone moved his musicians into the Bristol South swimming pool in Dean Lane in the 1960s when it closed for the winter. Boards were put over the pool to accommodate the dancers.

Do you have any photos tucked away somewhere of the Grand Spa ballroom, or of people enjoying themselves there, in its 1960s heyday? If so, we’d love to see them, and perhaps publish them on Flickr, so that others can see just what it was like.

2016 – Once-popular Bristol ballroom left derelict for decades could be brought back into use.

For decades, the once-popular Grand Spa Ballroom below the Avon Gorge Hotel in Clifton, has stood empty and neglected, a relic of bygone days.

Now however, there appears to be plans to bring the former venue back into use by the Hotel du Vin, the new owners of the Avon Gorge Hotel.

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on http://www.buildercar.com/six-1950s-sedans-take-on-lime-rock-park/

Six 1950s Sedans Take on Lime Rock Park

Emerging from World War II in 1945, the world’s automobile industry had plenty of rebuilding to do, not just in Europe, where bombs had dropped for years, but also in the U.S., where most factory capacity had been turned over to war work. The industry’s enthusiasm for getting back to what it loved most — designing, building, and selling new cars folks wanted to buy — showed. By the turn of the next decade, the cavalcade of automotive progress was back

in full swing.

The 1950s: Eisenhower’s Interstate Highway System, McCarthyism, and the Red Scare. The rise of the military-industrial complex, the ascent of the Jet Age, the Space Age, and teenage culture. Bikini Atoll, Sputnik, “Rock Around the Clock.” Marilyn Monroe, Brown v. Board of Education — choose your change cliché, the ’50s had it. For cars, too, change was everywhere.

To experience this former future shock today, we summoned seven significant ’50s sedans to a race- track also born of that time. Lime Rock Park in northwestern Connecticut, along with Willow Springs International Raceway in California and Wisconsin’s Road America, is one of the three longest continuously operating circuits in the U.S., celebrating its 70th anniversary in 2017.

A group of fine four-doors from seven carmakers. These classic cars ooze national character and idiosyncratic engineering.

Why sedans? They were the default choice during the era, available in all flavors and sizes. Our test roster tends toward middle-

and high-end sedans because that’s where technology was sweetest. These old cars strike us as fresh, wildly different from one another in conception, construction, and constitution, with dissimilar powerplants and almost hilariously incongruent shift patterns for their different transmissions. They’re all sedans, but each is so different from the others. The fact manufacturers on both sides of the Atlantic were defining themselves and creating what they created without the aid of computers was a gargantuan accomplishment.

1950 Citroën Traction Avant

In many ways the most up-to-date of our septet in conception, the Citroën’s engineering has roots in 1934, when the firm made its first real foray into futuristic engineering with this very model. Traction Avant equals front-wheel drive, and along with unibody construction it’s what we expect today, but in the 1930s the Tractions had no direct mainstream competitors.

With a long and low roofline laid out smack in the heart of the Depression era by Flaminio Bertoni (no relation to the Italian Bertone design house, which worked with Citroën years later), the Traction Avant must’ve really struck a chord in the ’30s. With wheels at the ragged edge of each corner and a postage slot for a windscreen, the car looks retro-sleek and incredibly gangster today—and probably always did. It is a credit to Bertoni and the French, who don’t always get their deserved credit for their contributions to OG style. André Lefèbvre is credited with the engineering, so advanced it carried — or should we say pulled — Traction production into the mid-’50s.

Modernity aside, the Traction has an engine as old a lump as it looks, with less than 60 horsepower to boot. But this well-worn example gets out of its own way. Despite 66 years in service, it keeps up with modern traffic, comporting itself nicely with firm but not unbearably heavy steering that rarely belies the front-drive arrangement and a ride that is velveteen by the low standards of 1934. The present caretaker of the car, which was once the property of racer Sam Posey’s feisty mother, is shop owner and former Group 44 mechanic Don Breslauer. He says that once you get used to it, it is easy to use the four-speed manual box with the gear lever sprouting from center dash.

Chrysler’s imposing dashboard is another distinctive feature that set sedans of the day apart from one another.

1952 Chrysler Saratoga

Chrysler’s 180-hp, Hemi-headed FirePower V-8 was big news in 1952. Journalists were blown away by the acceleration to 60 mph, a 10-second jaunt that was about as fast as it got back then. The four-door, six-passenger sedan brought to the track by Charles “Chuck” Schoendorf, who also owns a Saratoga coupe, was the subject of a splendid restoration prior to purchase.

Hydra-guide power steering was an exciting new option for Chrysler in 1952, and with the Saratoga’s 18.2:1 steering ratio and 4.75 turns lock-to-lock, you might argue an essential one, but this car doesn’t have it. Body roll aside, the Chrysler feels solid, comfortable, and well made. It rides impressively with front coil springs and a substantial heft of 4,000 pounds to haul around. It steers and corners better than you might fear, and this Chrysler moves out like it means it.

People remain excited by the idea of a Chrysler Hemi some 65 years later, which speaks to a profound and enduring reality: Whatever century you’re in, gobs of smooth power make drivers smile.

Period plastics complement the painted metal dash, while a curious shift pattern may cause occasional botched gear changes.

1952 Lancia Aurelia B10S

The Aurelia was the baby of Italian motoring legend Vittorio Jano, who would design the great Lancia D50 Formula 1 car of 1955 following an already brilliant career in the employ of Alfa Romeo. This relatively early example of the sedan — a model made between 1950 and 1958 — sports Lancia’s signature unibody construction, which the company pioneered in the 1920s. It also has the world’s first production V-6, a forward-thinking 60-degree overhead-valve engine manufactured entirely from alloys, with hemispherical combustion chambers echoing the industry’s renewed love for older performance ideas that worked.

Climbing into the Aurelia, you first notice its pillarless construction; when the doors open, there is nothing but open space where the B-pillar ought to be. Although likely not the safest layout, it looks elegant, airy, and inviting. Better yet, the doors open and shut like exquisite jewelry — proof of serious engineering and superior build quality, which ’50s Lancias are all about. Ditto the precision column-shift that selects gears smoothly in a faraway rear transaxle, even though the shift pattern is backward to the others in this group.

The V-6 could displace up to 2.5 liters, but this B10S (the S stands for the Italian “sinistra,” or “left,” as in left-hand drive) makes do with 1.8 liters. So while it pulls well, revving enthusiastically to 4,500 rpm and beyond, it’s not the rocket ship that many American luxury buyers of the day wanted. It did, however, tempt our friend Santo Spadaro of New York’s Domenick European Auto, who imported it from Europe. Values for Aurelia convertibles and coupes (such as the one he sold too soon) are off the chart, and Aurelias like this are four-door gems. Not just of post-war Italy but in the context of all automobiles, ever.

1955 Chevrolet Bel Air

Chevrolet embarked on a new era in 1955 as it built a mainstream sedan that piqued consumer desire with new, modern, slab-sided styling and exciting new vistas of performance. The latter came courtesy of a freshly designed high-compression V-8, an extra-cost option to Chevy’s standard Blue Flame six. Displacing 265 cubic inches in its first incarnation, the iron V-8 credited to future General Motors president Ed Cole, then a young engineer, lives today in the much changed but still recognizable Chevy small block.

It’s hard to find an unmolested ’55 Chevy—one that hasn’t been cut, torched, crashed, rodded, or resto-modded—and finding one with four doors is even harder. Richard Bogart, 83, bought his restored stock sedan a few years back, as it reminded him of his ’50s honeymoon with his recently departed wife. Its pristine condition and four doors make it a rarity, though it was converted at some point to eight cylinders from the six it was born with.

This example’s manual column shift directs three forward gears, and the “three on the tree” is a breeze to use. The Bel Air is not a unibody, with the heavy separate frame and lack of rigidity that tends to follow, but the driver is insulated from the jarring road by power-assisted steering that is close to flat-line numb. Four-wheel drum brakes are fine, if guaranteed to fade after hard use. For decades, ’55s were the muscle man’s first choice for a reason: fast in a straight line, looks cool—a formula that never tires.

Alfa’s first pass at the mass market is at once spartan and sophisticated, with minimal adornment yet a distinct sense of style, allied to performance most excellent for its day.

1957 Alfa Romeo 1900

The four-cylinder 1900 is not only the first Alfa with unibody construction but also Alfa’s first production model built on a line, the first fruit of its first modern factory. Built by American taxpayers with Marshall Plan money after the war, it vaulted the distinctly bespoke company into 20th century mass production.

Alfa’s 1900 came in many body styles, this one being the factory’s own four-door, steel-bodied Berlina. Its new-for-1950 1.9-liter four-cylinder engine incorporated racing practice with twin overhead camshafts. The 90 horsepower it generates in standard, single-carburetor form is enough to propel the base sedan we drove to a top speed of 94 mph. With a svelte 2,400-pound curb weight, it’s not surprising 1900 sedans won the Targa Florio and Stella Alpina races early in the model’s life.

The 1900’s four-speed gearbox is fluid, almost creamy in action, and its column shifter boasts simple operation. Ride is compliant with coil springs all around, and the steering feels tight and lively as we identified a refreshing absence of old-car rattles, though body roll is Old World substantial. A duo-toned interior with green vinyl accenting the dash and cloth seats with green wool inserts liven up the painted metal and sober instrument panel in a car that meant business—and in doing so helped create one.

The leather-lined interior and airplane gauges are a far cry from the soda shop look of the day, but with them Jaguar helped define luxury tastes and expectations for generations.

1958 Jaguar Mark I 3.4

The Jaguar Mark I debuted in 1955 with a front-mounted straight-six engine and rear-wheel drive. Of the cars here, it’s easily the sportiest and most fun to drive. It seems the most rigid, with the most aggressive suspension, the lowest roofl ine, and the sportiest demeanor, thanks in no small part to a strong engine and the only fl oor shifter in our group.

Launched as the Jaguar 2.4 liter, today’s example is a later model with 3.4 liters of displacement and 210 horsepower. It has a top speed of 120 mph and does 0-60-mph sprints in less than 8 seconds, which was hugely fast in the ’50s. Jaguar’s first entrant in the small luxury car market, which the Mark I helped to grow significantly, the model was built around Jaguar’s awesomely versatile XK engine, which in tuned form had powered the company’s contemporaneous Le Mans-winning D-Types. The base Mark I would have benefited from better brakes, although discs were a regularly specifi ed option in all late-production cars, including this one. The combination of a rigid if arguably overbuilt unibody, a sporty chassis with strong disc brakes, and a manual gearbox—in this case, a four-speed on the floor with an electrically overdriven fifth gear—was and still is ideal.

The Mark I 3.4 is an emotive archetype for Jaguar sedans to the present day. In its day the car found success in saloon-car racing, and it’s easy to see why owner Todd Daniel threw a cage in it and went racing.

Mercedes used leather and wood to a rugged, less sensual effect, but for solidity and reliability, Benz was in a class of one.

1959 Mercedes-Benz 219

Daimler’s sterling reputation in the U.S. began in 1953 with the introduction of the so-called “Ponton” series of Mercedes-Benzes. Drive this one and you know you’re in a carefully considered, high-quality machine from a long-respected German manufacturer.

Owner Jaime Kopchinski found this car in a warehouse in Hackensack, New Jersey, where it sat for the better part of half a century after driving but 12,000 miles from new. Seeing how Kopchinski is a senior telematics engineer for Mercedes, he is entitled to an employee discount on parts from the company’s Classic Center, which made reconditioning this smallish Benz sedan much easier. The Ponton series, which ran until 1962, comprised a suite of engines and wheelbases, all with fully independent suspensions, this being a W105. (Other related models include the W180, W121, and W128.) This Mercedes-Benz 219 is a unibody, the company’s first, and it has an inline-six displacing a modest 2.2 liters. The engine is notable more for its smoothness than any ability to snap necks.

Mercedes calls the Ponton the true ancestor of today’s E-Class. Silken smooth with a comfy ride, the 219 gives its driver a tangible sense of well-being, a cost-no-object excellence to which most other machines can only aspire.

Visit Lime Rock

Lime Rock Park is a fast, fun track in a quiet, densely forested part of Connecticut that’s really easy on the eye. Visit and stay at the Sharon Country Inn, less than 2 miles from the track and newly renovated by its helpful and jovial owner, Edi Cania. With a new wing, it now has 28 rooms, but be warned: Book in advance, especially for race weekends.

Sharon Country Inn, 1 Calkinstown Road, Sharon, Connecticut 06069-2127, sharoncountryinn.com

For track and events information visit: limerock.com

Source link

0 notes