#grassland

Text

April 2, 2024 - Yellow-bellied Seedeater (Sporophila nigricollis)

Found from Costa Rica south to Brazil and northeastern Argentina, but not in much of the Amazon basin, these seedeaters live in grassy habitats. Usually foraging in small flocks or pairs, they eat mostly grass seeds. They weave cup-shaped nests from grass, fibers, twigs, and spiderwebs near the ground in bushes or trees. Females lay clutches of two or sometimes three eggs.

#yellow-bellied seedeater#seedeater#sporophila nigricollis#bird#birds#illustration#art#grassland#birblr art

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

#naturecore#nature#scenery#aesthetic#plants#plants and trees#travel#florals#forestcore#forest aesthetic#grassland#green#greenery#traveling#greencore#moodboard#green landscape#green nature#fairycore#paradise#photography#explore

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Cave art inspired deer herd.

#Art#drawing#cave art#primitive art#pleistocene#ice age#digital art#deer#doe#buck#fawn#herd#nature#gold#palaeo#palaeosinensis#illustration#red#grass#grassland

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

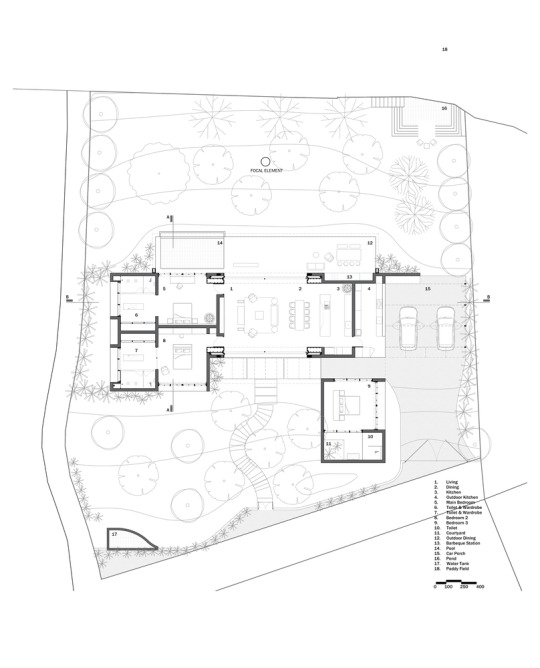

Alarine Earth Home, Koshi, India,

Zarine Jamshedji Architects Conceived in collaboration with builder Cornelis Alan Beuke

Photo Credit: Syam Sreesylam

#art#design#architecture#interior design#interiors#minimalism#earth home#india#koshi#alarine#zarine jamshedji#cornelis alan beuke#solar energy#sustainability#grassland#holistic#green roof

839 notes

·

View notes

Photo

by Tim Allott

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Half the land earmarked for regeneration by the 34-country African Forest Landscape Restoration Initiative (AFR100) is in savannah or other non-woodland areas, says a paper published in Science on Thursday.

[...]

“There is a vast area of non-forest across Africa that is earmarked for restoration, principally through tree planting,” said Catherine Parr, a co-author of the paper and an ecologist at Liverpool, Pretoria and Witwatersrand universities. “The focus solely on forests and trees is highly problematic for these non-forest systems.”

The AFR100 project seeks to restore at least 100mn hectares of degraded land — an area the size of Egypt — in Africa by 2030, with big plans in countries including Cameroon, Ethiopia, Mali and Sudan. The initiative’s backers include the German government, the World Bank and the non-profit World Resources Institute.

But about half of the approximately 130mn hectares that African countries have committed to restore through AFR100 is earmarked for non-forest ecosystems, principally savannahs and grasslands, according to the paper.

[...]

The dispute over the research highlights growing friction over pledges by philanthropists and corporate leaders to plant a trillion trees worldwide. These ambitious plans face obstacles including potential shortages of available land suitable for planting. Other questions concern how effective newly planted trees are at locking in significant amounts of carbon dioxide — and how vulnerable they are to risks such as forest fires.

“There’s such a big focus at international level on deforestation, but the level of sophistication and understanding about ecosystems writ large is really low,” said Alex Reid, a policy adviser on nature and finance at Global Witness, a non-profit group.

Some scientists and conservationists argue that it is better to focus on preventing deforestation, by creating incentives to retain woodland areas. Greenhouse gases released by deforestation make up about 11 per cent of global emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

x

282 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Credit: Erik Mclean

#nature#fence#outdoors#field#grassland#countryside#farm#rural#meadow#ranch#pasture#building#rancher#wilderness#farmland#rustic#farmstead#land#homestead#grain#agriculture#acreage#sunset

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Grassland Slinker" 11"x14" markers and acrylic

with special guest stars the turkeys

#art#traditional art#coyote#acrylic#animal art#painting#primitive wiggles#mixed media#naive art#grassland#tombow dual brush pens

264 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tripótamos, Tinos island, Greece by Blaz Purnat.

#greece#europe#travel#wanderlust#landscape#mountains#country#village#grassland#tripotamos#tinos#cycladic islands#greek islands#large#cyclades

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

December 24, 2023 - Andean Siskin (Spinus spinescens)

Found in the Andes in parts of Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador, these finches live in open habitats with some trees and bushes. Foraging in pairs and groups on or near the ground, they eat seeds from a variety of plants, as well as flowers. Little is known about their breeding behavior, though adults in breeding condition have been found in August, they have been seen building nests in June, and recently fledged chicks were observed in March.

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

#naturecore#aesthetic#nature#flowers#flowercore#plants#gardencore#garden#forest vibes#cottage style#cottagecore#cottage aesthetic#cottage vibes#cozy places#explore#cozy vibes#traveling#grassland#landscape#photography#florals#aesthetic florals

828 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jeremy Cai

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dorset, England by Anthony White

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, I'm heavily interested in the kinds of environments people generally experience and care about, and I'll be making a few polls like this with slightly differently phrased questions. I am coming at this from a mostly American perspective to narrow things down and also because I feel like a lot of my followers are probably American, so keep that in mind.

As always, please reblog for a larger sample size. I greatly appreciate any participation!

639 notes

·

View notes

Link

To understand how grasslands became “wastelands,” we need to understand how British colonists valued the high-quality timber of India’s forests. They harvested trees for construction, laying railway lines in India, and shipbuilding, all of which supported Britain’s economic expansion and war efforts. The British also undertook plantation operations to maintain the supply of timber. This led to the formation of the Imperial Forest Service, whose main mandate was to aid in British silviculture. At the same time, the British government created the baze zamin daftar (wasteland department) to map and control areas, like grasslands, that they deemed economically useless.

The forest service also called grasslands “degraded forest,” because they believed these more open swaths of land could have held forests but for what they called the “destructive” practices of the Indigenous and pastoral communities living there. Both these designations ultimately motivated the conversion (or “restoration”) of grassland habitats into forested landscapes, as we show in a recently published paper that critically analyzes grassland conservation policies in India. This also ushered in the displacement of Indigenous and pastoral communities that depended on grasslands for livelihood. Colonial authorities criminalized (through regressive acts like the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871) communities and unjustly denied them any control over these “wastelands.” The colonial government was particularly wary of pastoral or “wandering” communities and invoked the Criminal Tribes Act to penalize them for activities that included grazing of livestock—an important mechanism to maintain grassland habitats. As Atul Joshi and colleagues report in their paper on the colonial impact of forestry on the high-altitude shola grasslands, colonial officers also began converting such grasslands into fuelwood plantations of Acacia and Eucalyptus to supply to settlers, while prohibiting Indigenous communities from using them for firewood.

As forests are ecologically complex, so are grasslands. They range from the dry and semiarid grasslands of Central and Western India, to wet grasslands on riverbanks of the Himalayas, to high-altitude grasslands in the Western Ghats and cold desert grasslands in North India. These lands also have deep cultural significance based on their role in pastoralism or fire practices. Yet, the historical framing of grasslands—and indeed other non-forested ecosystems—as “wastelands” continues to hamper preservation efforts.

Whereas colonial officers had economic motivations for converting grasslands, today governments worldwide are banking on forests and foresting to mitigate climate change. To this end, there are global efforts to map potential areas for afforestation initiatives, but these efforts often identify grassland ecosystems as good candidates for afforestation, threatening more than one million square kilometers of grasslands in Africa, for example. In India, we find something similar: large areas of grasslands earmarked for large-scale afforestation activities.

Yet, grasslands could be equally good—if not better—at storing carbon. Apart from being costly and flawed, a carbon sequestration-based strategy also neglects the ecological and social value of grasslands by converting them to monoculture forests, which do not provide the same ecological benefits.

657 notes

·

View notes