#funeral rites

Text

On the Topic of Patroclus’ Funeral

So I really wonder how excessive the funeral rites for Patroclus were in the context of who he was, society-wise. And sometimes I just have to scream out my thoughts about things, so be warned about a very long wall of text.

Patroclus was the son of Menoetius of Opus, who may or may not have been a king, making Patroclus a possible prince of Opus. Due to having killed a boy over a game of dice when he was young, Patroclus had to be exiled and became subservient to Achilles. He seemed to have played the role of an older playmate and mentor, although Achilles is said to have taught him things, too (e.g., the healing ways of Chiron). Serving as Achilles’ companion, he is seen to cook and care for Achilles and serve food to guests, delivering messages and ordering slaves to do Achilles’ bidding.

(This fits with the meaning of the word therápōn, which Patroclus is described as (acc. To Wiktionary, which references various dictionaries, the word therápōn (θερᾰ́πων) can mean: 1) companion of lower rank, comrade, attendant, aide and 2) servant, slave.)

On the other hand, Achilles has no problem giving Patroclus his 2.500 men strong Myrmidon army to lead, even though Patroclus is not mentioned* as a captain or general of his troops (these are his nephew Menesthius, Eudorus, Peisander, his tutor/second father Phoenix, and Alcimedon).

(*Outside of The Iliad, Patroclus is also listed as a leader of the Acheans by Hyginus, contributing ten ships from Phthia to Agamemnon’s war on the Trojans.) This might have to do with his other titles, as Patroclus is also called a tamer of horses (or rider of horses), specifically Achilles’ horses. These were immortal steeds with a great temper, described only to be able to be restrained and guided by Patroclus. Patroclus was also Achilles’ charioteer (the horses were so sad about his death that Homer made them cry and unwilling to move over his death). Aside from that, Patroclus is also called the best spearman of the Myrmidons.

So we have an exiled prince demoted to servant/squire status to another man (also a prince, but of nobler lineage) and a competent soldier and charioteer/horse tamer.

And this is what he’s getting when funeral rites are being performed for him:

>>The laying out of the body<<

Achilles orders that Patroclus’ body be washed of the blood (and dirt) caking it. Patroclus’ body has two spear wounds – one between his shoulder and a fatal one on his belly – but has also been tugged around like a ragdoll by the Greek and Trojan soldiers as they were fighting for him, and features other mutilating wounds given to him post-mortem.) The wounds are filled with unguent, and his body is laid on the bier, shrouded with a linen cloth from head to foot, with a white robe on top.

Achilles and the Myrmidons mourn him all night long. Achilles goes out to kill Hector the next day, but hesitates because he fears maggots and flies might defile Patroclus’ corpse. His mother, the goddess Thetis, infuses ambrosia and nectar through Patroclus’ nostrils to preserve it. So his corpse will look fine for a while.

After Achilles has killed Hector, Patroclus beseeches him in a dream to give him to the fire, as he cannot enter Hades with his body in its current state. He also asks for his ashes to be buried together with Achilles, so they may be together in death as they had been in life. Achilles agrees and plans a burial mound for the two of them to be built (Achilles knows, by prophecy, that he will not live to return from Troy alive).

>>The funeral procession<<

Achilles takes on the role mainly performed by relatives, mostly by women, during the funeral rites. (If you look at their family tree, they are related by Aegina, who gave birth to Menoetius with Actor. Aegina is also the mother of Aecus by Zeus, who fathered Peleus.) Possible kinship with Achilles aside, Patroclus does not have relatives with him where he died. So his comrade in life and arms, Achilles, is the closest thing he has. Aside from that, Achilles is also the supreme commander of the Myrmidons, and if Patroclus was their best (and possibly noble) (spear)man, this might play a role, too.

Achilles orders the Myrmidons to don their armor, and a procession of charioteers mounted on their chariots and a host of foot soldiers marches with Patroclus in the midst, carried by his (non-specified) friends. Achilles walks behind, supporting Patroclus’ head. The Myrmidons also cut off the locks of their hair and threw them on the corpse until they covered Patroclus like a garment.

After being set on a wooden structure, Patroclus also gets Achilles’ locks of hair placed in his hands, which Achilles had grown in the context of a planned offering to the river-god Sperchious. Achilles then rouses the Myrmidons to weep for Patroclus almost until sunset.

Achilles then sends most of the men away (to take a meal) until only the closest mourners are left to manage things, but he asks the Achean leaders to stay. They then piled up wood to make the 100 ft.² pyre with the corpse on top of it. Then Patroclus received the following offerings to his pyre:

numerous sheep and cattle placed around the pyre,

fat from the livestock offerings wrapping the corpse from head to foot,

two-handled jars of oil and honey,

four horses,

two of the nine dogs Patroclus fed beneath his table,

twelve noble sons of the Trojans (an unusual type of sacrifice).

Achilles prays to the winds, Boreas the North-wind, and Zephyrus, the west wind, as the pyre would not catch flame. These gods step away from a feast to fulfill Achilles’ wish while Achilles pours libations (untold amounts of wine) for them all night long while grieving for Patroclus.

>>The interment of the cremated remains.<<

After falling asleep next to Patroclus’ pyre, Achilles is roused by his gathering comrades. He orders them to quench the pyre’s last flames and collect Patroclus’ ashes from the middle of the pyre, separating it from the rest.

Per his wishes, Patroclus’ ashes are placed in the golden urn Achilles received from his mother, which is sealed with a double layer of fat. The urn is then covered in linen and brought to Achilles’ hut (Patroclus did not have a hut of his own and slept in the same room across from Achilles).

Achilles tells the others that the urn should remain sealed until his own death comes. He bids Patroclus’ funeral mound be built and whoever of the Acheans survives Achilles to build their joint mound broad and high.

>>The funeral games<<

The other men want to leave, but Achilles also decides to hold funeral games for Patroclus. He sponsors many prizes for them, such as cauldrons, tripods, horses, mules, oxen, female slaves, cooking and offering dishes, armor, and gold.

The games consist of:

a chariot race,

a boxing match,

a wrestling bout,

a foot-race,

armed combat,

a throwing competition (with a mass of iron),

an archery contest (pigeon shooting).

And that concludes Patroclus’ funeral. This part of The Iliad spanned an entire book of the 24 books the Iliad consists of (Bk XXIII, covering 897 lines of text).

In comparison, Hector’s funeral – from Priam bringing back the body to Troy (Bk XXIV:677-717) to the end of Hector’s funeral (Bk XXIV:776-804) consists of only 127 lines of text.

Now, one could argue that the reader/listener of The Iliad would be bored with another excessive description of yet another warrior’s funeral. But even if Homer summarized the events, they only consisted of men gathering wood (for nine days), placing Hector’s body on top of the pyre, and setting it ablaze. Yes, mourners (e.g., Hector’s brothers and friends) are mentioned before and during the proceedings. They also gather Hector’s ashes from the pyre the next day, place them in a golden urn, wrapped in a purple robe, and put the urn in a hollow grave. The grave is covered with large close-set stones; above that, a barrow is piled up with sentinels posted outside in fear of the Greeks. Afterward, Priam holds a funeral feast.

It might be possible that the funeral proceedings of the Trojans are not the same as that of the Greeks, even if Homer is a Greek author. Yet, Hector was the son of King Priam of Troy and the Trojans’ crown prince and best warrior. He defended Troy honorably and slew many of the Achean warriors. If anyone deserves a lavish funeral, it would be Hector. While the reader/listener can assume the proceedings were as luxurious as can be, it isn’t written that way.

It is also interesting that Priam held funeral games for Paris (when he thought his baby boy had been killed as a sacrifice to save Troy), but he does not hold funeral games for Hector. Maybe no funeral games were held because the city was full to bursting with refugees fleeing the marauding Greeks over the years, so there was no space left to do this. It could also be due to the Greeks possibly overrunning the city at any given moment (after the twelve days of truce Priam and Achilles had agreed upon for the funeral rites of Hector were over), so the Trojans did not dare hold any games.

But this is also not mentioned anywhere in The Iliad.

Even if funeral games had been held for Hector, the rituals would only be comparable to those for Patroclus and would not go beyond them.

As it is, Patroclus’ funeral rituals seem excessive compared to his social standing. From Achilles’ point of view, they were probably just the right amount of excessive, measured against how much Patroclus meant to him.

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

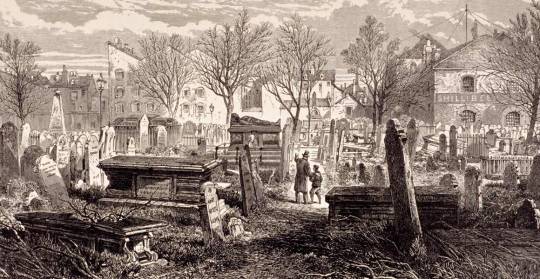

the London Necropolis

It was 1850 and London had a problem.

All right. London had a lot of problems in the 1850s. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, London had seen its population boom so quickly that the city didn't have time to make room for everyone. Housing developments and slums sprang up seemingly overnight, cramming as many people into a warren of rooms, and partitioned off rooms. as could be fit. Poverty ran rampant, cholera outbreaks swept through districts regularly, the conditions in the factories, where small children were often also employed, were deadly and the environment itself was a lung-clogging morass of soot and sewage. Some made their fortunes and managed to rise through the layers of society but many simply hung on to the bottom rungs of it for as long as they could before their hands were wrenched off to make way for others. And that didn't just apply to the living.

The dead didn't know rest either.

It didn't take long for the graveyards of London to hit full capacity with the population influx. Even with the body snatchers, working to retrieve bodies for local hospitals and schools as well as even more unsavory employers almost as soon as the grieving family left the plot, couldn't keep up with the massive amount of bodies that needed to be buried in the local cemeteries week after week, month after month, year after year. The problem grew to the point that gravediggers, hitting older coffins would simply continue digging, tossing rotted wood and whatever body parts were left into the dirt pile behind them, making room for the newest arrival in the plot. Graves got so shallow that the bare layer of dirt over them easily washed away and utterly failed to keep what was slowly decaying in the boxes covered. Church goers learned to bring perfume covered handkerchiefs to Sunday services, if they were lucky, to hold over their noses the entire time, trying to blot out the smell seeping under the doors and into the confined interiors of the buildings. Flies and other, even more unpleasant, scavengers were impossible to get rid of, lured by the ease of a quick meal and a place to take up residence. Health inspectors, and many Londoners of the time, blamed the miasma rising from the graveyards for many of the disease outbreaks that swept through the city. Something had to be done.

An amendment was passed in 1852 prohibiting most new burials in the more populous sections of London. The problem was - where did you put the bodies then?

In 1832, the Magnificent Seven, seven large plots of land outside London, had been remade into cemeteries. One business group had higher aspirations than that though. In 1854, the Brookwood Cemetery, the largest cemetery of the time, opened for business. It soon became know by a different name.

The London Necropolis.

And the London Necropolis Railway was there to make sure everyone, dead and alive, found safe transportation there.

Railroads and their trains were still new at that time. Loud and noisy, belching steam and smoke into the air, trains weren't seen as a dignified way for the dead to travel to their final resting place and eternal peace. Worse yet, travel by train might lead to a mixing of the classes, dead as well as living (gasps of alarm and swooning!). Who wanted their sweet genteel maiden aunt's body to ride in the same cargo car as some low level rake's corpse?! Why it was undignified (and very against the social divisions of the time)! Even in death, standards must be applied.

Trains, however noisy and undignified, did offer a distinct advantage. They were cheap. And they ran regularly on a schedule you could plan around, daily in fact, including Sundays. As for social distinctions - well, the LNC had a solution for that too. Depending on the money you were willing to spend, the rail offered first, second, and third class funerals, with separate train cars for each class, living or dead. Knowing that most passengers from other stations would be reluctant to ride a train that had carried dead bodies, the LNC bought new cars and engines specifically for the job, kept separate from the other routes of train travel. They laid track specifically for the job as well, so that only the necropolis trains traveled to one of the two separate stations in Brookwood Cemetery. Mourners left the Waterloo Station in London and road the train, with their unique luggage, to either the Southern Anglican Station or the Northern Station, where the 'nonconformist' section of the burial plots were. While the trains originally only ran for funerals, enough mourners wanted to return for visits to the graves of their loved ones and eventually, after about ten years, the LNC built a third station for that purpose. Almost immediately, a small hub of shops and services sprang up around the new station to cater to, and prey on, the arriving mourners. For fifty years, until 1900, the funeral trains ran on schedule, ferrying bodies, and their loved ones, back and forth between London and the Necropolis. Even after that time, the trains still ran 'as needed' until, finally, in 1941 the London Necropolis station was bombed during the London Blitz. It was the final blow to an already declining system. The station was never rebuilt.

By the 1950s, funeral trains were almost obsolete and the last one in England carried its lonely cargo in 1979. By 1988, the British Railway didn't carry coffins anymore. Time, and more efficient methods, had passed the Necropolis funeral trains by. The tracks overgrew with weeds where they weren't torn up for scrap and the only wistful train whistle left to linger in the chill evening air at the grey and abandoned gates was the long, low ghost of a memory.

#superstition#london necropolis#london necropolis railway#funeral train#LNC#brookwood cemetery#train#trains#funeral#funeral rites#history#victorian#victorian era

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over the weekend I was rather unexpectedly called upon to perform funerary rites for an infant. While I have assisted with and participated in pagan funerary rites before, this was to be the first passing I would officiate and tend to on my own. The parents of the deceased child did not know me, but were so lucky as to be in an area with a thriving enough pagan community that a priestess was available last minute when they needed her. I feel so blessed to be part of such a community. Goddess willing there will be a time when no parents in any community will have to face such an ordeal without the spiritual support they need.

Ministering to a room of strangers- most of them not pagan and all of them come from far and wide to grieve this heavy loss together- was a truly humbling experience. The whole two days I had before the memorial to prepare I was racked with nerves, but the moment I spoke to these people and stepped up to give the blessings a wave of serenity washed over me. I was grounded and steady- more than I’d been in days if not weeks! It was one of those moments when a priestess truly gets to feel Goddess channeled through her, and to know with a very calm and simple clarity that the words, comforts, and blessings she is bestowing are filled with the Goddess’ own holy weight.

#goddess religion#great mother#mother night#pagan#tw death#tw child death#funeral rites#I got a lot out of the experience I think#and i believe that the family took a great deal of comfort from the rites#personal

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm working on stuff for Funeral Rights, the sequel to Cleaning the Gravestones (read here!). Let me know what you think, or if you have any suggestions!

Funeral Rites starts about 3-4 years pre-canon, when Vlad (Senior Lab Manager & Assistant CTO) receives a job offer that the family can't really afford to refuse as CTO of Axiom Labs in Amity Park, Illinois.

This kickstarts some plot, in which Vlad and Harriet end up trying (and probably succeeding) in gaining custody of Danny and Jazz for the following reasons:

They're both mildly ectocontaminated, which should NOT be happening

Yes, the bruises on Danny are probably mostly from his bullies, but some of them are bigger than a child's/teenager's hand, and Danny won't explain them

Both kids avoid being at home at all costs

Vlad's so-far buried trauma regarding the Fentons

Important to note: the Fenton parents aren't evil in this. They're misguided, neglectful, don't like to take the consequences of their actions- basically, they're bad scientists and bad parents, but they aren't intentional about it.

Cleaning the Gravestones was largely about blending the natural and unnatural, accepting that not everything can be understood, not going out of your way to hurt what you don't understand, developing and using support structures, and building both platonic and non-platonic relationships. It's also about learning to hide in plain sight.

Funeral Rites is going to flip a lot of that on its' head. It's learning where the line you cannot cross is. There's a breaking down of support structures (Danny and his parents, Wes and his dad, Dani, Katie, and their dad once they learn he's a murderer), and choosing what, if any, relationship to build back.

It's learning sometimes the secrets you keep for your family's safety can really bite you. Finally, it's about gaining closure: maybe not everything is perfect, or even close, but if you can at least pick up the rubble, maybe you can build something again. Above all: what really makes a monster? Is it being inhuman? Or something else? And how much of our destiny can we really rewrite?

Due to length, everything else under the cut.

Obviously, some things are different from canon. Vlad hasn't stewed in anger/hatred over the Fentons, he's (mostly) moved on. He and Harriet are (happily) married. They've got kids. So Vlad can't be Danny's narrative foil. That will be filled by someone else.

Walter Weston is an ally in this, unlike in CtG, where he was the primary antagonist. He's able to accept consequences, and feels a lot of guilt; he's eager to make up for his actions any way he can. Wesley is a lot like his dad 10 years ago, though thankfully isn't cursed by a spirit of madness.

Jazz is tired of being a mother at 13, and doesn't know how to fix things. She wants to be a kid, for once in her life, and the Chin-Masters family is promising to help with that.

Danny starts off with feelings of jealousy;

#inthememetime#danny phantom#vlad masters#danny phantom au#redeemed vlad masters#harriet chin#harriet x vlad#bad news#dani masters#cleaning the gravestones#funeral rites

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Sepultura - Funeral Rites

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Considering adding "and take my blood and unused bone to craft a steel necklace with a large ruby set in it's center" to my will to make haunting easier.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

phantom memory

day 5 prompts: first meeting, shared cultural traditions

cross-posted to ao3 + codywan week22 masterlist !

wc: 1702

tags: grieving, mourning, funeral rites, hurt / comfort, angst, pre-relationship, panic attacks

The first time Obi-Wan gentled Cody down from a panic attack, it was just after their first major engagement. They’d had skirmishes up to this point, relief missions and raids on outposts and defensive stationing. Alpha-17 had returned to Kamino and Obi-Wan’s injuries from Rattatak were, for the most part, visible only as scars.

“Easy, easy,” Obi-Wan murmured, pulling his Commander by the rerebrace over to a corner and getting him to sit down. Cody went without protest, helmet clattering against the floor and shoulders hunching violently as he shook. Obi-Wan remembered his first true taste of combat, though it had been on a world far from here. The years had softened the memory to a phantom, eased by the mind healers he’d talked to and a mended bond with Qui-Gon—but Cody had neither of these.

“It’s alright.” Obi-Wan pulled one of Cody’s hands to his chest, not bothering to take the gauntlet off. He breathed in, exaggerating the motion to the fullest, and breathed out, Cody’s palm pressed flat to his sternum. In for a count of seven, hold for three, out for another seven-count. Cody’s greaves knocked against the insides of Obi-Wan’s knees and his head stayed bowed, free hand curled protectively over the vulnerable back of his neck. Obi-Wan kept his touches minimal and gentle; a brush to the inside of Cody’s wrist to check his pulse, the quick swipe of a thumb to the blood staining the soft skin just below his temple.

“You’re safe,” Obi-Wan said, the words melting into a quiet mantra of sorts. “You’re safe on the Negotiator in the hangar bay. I’m here with you. Nothing can touch you here. You’re safe on the Negotiator in the hangar bay.” He kept talking, slow and hushed, and Cody’s breathing started to level. His presence in the Force settled, no longer brittle and bright with leftover adrenaline and panic.

Cody looked up, then, eyelashes clumped together with tears unshed and eyes red with grief and exhaustion. He looked up like he was only just now seeing Obi-Wan for the first time: soot-blackened skin, mussed and tangled hair, bloodstained hands and robes. “General,” he said, apologetic and shamed all at once.

“It happens to the best of us. To most of us, really,” Obi-Wan said, keeping Cody’s hand pressed to his chest. The proximity seemed to soothe something in Cody—or maybe it was the talking. He shifted closer, this time deliberately knocking the edge of his greave against Obi-Wan’s knee.

“This isn’t my first rodeo, so to speak,” Obi-Wan continued. “Though Force knows I never… nothing of this scale. I never had any formal training, either. But my, my first time—” Obi-Wan swallowed and swiped the back of a hand across his mouth. Broad-scale melee combat always left a bitter, acrid taste in his mouth, like the bombs the Melida and the Daan had used to try and kill their young. “Well. I spent the next day or two heaving at the slightest provocation. I was all shaky and punchy, just fight or flight for hours and hours.” The resulting adrenaline crash—delayed by almost 48 hours—had nearly wiped him out.

“The sims should have prepared us,” Cody said, mouth thinning. He didn’t frown, because Commander Cody was a man with 1.5 expressions available for public viewing, but the lines of exhaustion and grief around his mouth were deeper than Obi-Wan had ever seen on him.

“No one was prepared for combat of this scope,” Obi-Wan reminded him. “I shan’t say what Alpha did the first time he got deployed with me, but suffice it to say that you aren’t the only one. It’s a perfectly reasonable reaction to what you are going through, Commander, and if I may say, you’re weathering it quite well.”

“Doesn’t feel like it,” Cody said, finally leaning back from his hunched position. His shoulders eased down and he looked away, hand unconsciously flexing against Obi-Wan’s chest. “I need to… the troopers…”

“About to start,” Obi-Wan told him. He’d been surprised to find out—as he understood it from Alpha, most clone troopers hadn’t inherited Mandalorian cultural rites from either Jango or their Mandalorian trainers. There were only vestiges of it: in names and fighting styles, the impromptu familial structures, the strong sense of hierarchy and martial prowess—and the recitation of the names of the dead.

“You know?” Cody didn’t look surprised, though that wasn’t remarkable. Cody was surprised by very little, in Obi-Wan’s albeit limited experience. He’d had enough time to get used to Obi-Wan’s chronic nosiness, he supposed.

“Some.” Obi-Wan gripped Cody’s hand and helped heave him up, bending back down to grab Cody’s helmet and pass it to him. “The Jedi have our own practices for mourning and I didn’t want to intrude on yours, so I’ve been making myself scarce.”

“Join us, this time.” Cody stood tall once more, though his eyes were still red and he held his helmet like a shield. Obi-Wan had no doubt that Cody had more practical and strategic knowledge in the terrible art of making war, but for all his training, he had only been at war for a matter of weeks.

“Oh, I don’t—”

“Demure doesn’t suit you, General Kenobi.” Cody towed Obi-Wan by the crook of his elbow further down the hangar to the first open corridor, the both of them slipping into the arterial system of passages and lifts that filled the Venator.

“My dear, everything suits me,” Obi-Wan said with an ostentatious wink. Cody only gave him a look marginally flatter than his normal expression, and Obi-Wan knew he’d won.

One of the larger mess halls had been converted into a gathering space. Troopers drifted in and out, interspersed with the odd non-trooper come to pay their respects. There were no bodies. There were no flowers or headstones. Soldiers of the Grand Army of the Republic were buried where they fell, immolated, or left to drift through space unending. Cody towed Obi-Wan right through the eddies of the crowd and they parted before him like minnows from a shark. Murmurs rose and fell around them: names, serial numbers, memories of the dead. Cody’s lips were moving, silent, as they approached the far wall.

“What do Jedi do?” Cody asked, looking to Obi-Wan.

“Pyres.” Obi-Wan folded his hands together and wished for the robe he’d left riddled with blaster holes on the battlegrounds of Christophsis. “Dead Jedi are incinerated, their ashes laid to rest under the Temple. Depending on their final wishes, their sabers may be destroyed with their bodies, kept at the Temple, or passed onto lineage members for continued use.” He remembered the warm, living weight of Qui-Gon’s lightsaber in his hand, after Naboo. It had never felt quite right like his own, but he hadn’t been able to keep himself from holding on—just for a little longer. He was always grasping for time, it felt, for just a little more from the galaxy.

“Do you keep their names?” Cody unlatched his vambrace and flipped it around to show Obi-Wan. The underside was scrawled in a cramped, untidy hand, one that Obi-Wan recognized as Cody’s when he was in a rush. Most of them were only serial numbers, nameless CCs inscribed long enough ago that their edges were starting to fade.

“No,” Obi-Wan said, soft. “They are one with the Force now, as we all will be one day, and the Force is with us.”

“I see.” Cody’s expression was still, but his Force presence was a deep well of quiet contemplation.

“We sing,” Obi-Wan said, finally. “When the pyres are lit.”

Cody looked at Obi-Wan for a long moment, silent among the countless hushed voices filling the hall with memories. His attention was tectonic, shifts in his regard subtle and slow yet deep. Obi-Wan knew what he would ask before he even opened his mouth, and yet the sound of Cody’s voice struck something deep within him, like a bird startled into flight.

“Would you sing, General, for my brothers?” Cody asked, nearly close enough for his cuirass to brush Obi-Wan’s chest if they both inhaled at one.

Obi-Wan didn’t answer. He found himself clearing his throat and squaring his shoulders almost at a remove from himself, the feeling of being unbearably sweaty and achy falling away as he let the first notes tumble from his throat. He hadn’t sung in so long that the start was choppy and discordant for a stanza or two, and then the muscle memory took over. It was odd to sing by himself and for a crowd of non-Jedi but he could feel the warm static of Cody’s appreciation by his side and it kept him until the last note ringing high and clear in the vaulted hall.

Cody thanked him, at the end. Obi-Wan only inclined his head, unspeakably weary. It wasn’t often that they buried one of their own, but with the war starting and Jedi and troopers conscripted to fight…

The rest passed in a blur colored by the sticky-tacky blood cooling down Obi-Wan’s side and the feel of his robes sticking to him with cold sweat. He spoke to a handful of troopers and offered comfort and touch in equal measure: Cody did the same, or so he presumed, and then Obi-Wan walked Cody to his quarters.

“Rest well, Commander,” Obi-Wan said, quiet. The fluorescent lights were too loud and too bright, buzzing in his peripheral hearing and turning the corridor into a nightmare of white glare.

“You too, General,” Cody said. He gave Obi-Wan another long look, again like this was the first time he was seeing Obi-Wan, and Obi-Wan tried to rein in the impulse to feel flayed and skinless. Something about Cody—no. Cody was not a man that invited weakness in his vicinity, but he sought it out, worming through defenses and levering them wide open. Obi-Wan didn’t—couldn’t—take it personally. He simply seemed to have ever more weaknesses where Cody was concerned, was all. When he left, pacing further down the corridor, it was with the phantom feeling of Cody’s hand clasping his shoulder, the memory of the touch searing like a brand.

#codywanweek2022#sol's codywan week 22#hurt / comfort#angst#funeral rites#fanfiction#fic#fanfic#tcw#the clone wars#212th attack battalion#sw#star wars#panic attacks#a heat rash in the shape of the show me state

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean Genet, Funeral Rites

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Currently re-reading this...

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video of "Views of an Imaginary City: The Krokuta Burial Pits"

Jim Avis’s sensitive video interpretation of my admittedly quite bizarre imagining of an alternative funeral rite (though one inspired by traditional practices in East Africa). The pohutukawa is a real tree, btw, native to New Zealand. It’s bright red flowers blossom in December, and for this reason it is also known as a New Zealand Christmas tree.

youtube

View On WordPress

#funeral rites#hyenas#imaginary city#james avis#japanese prints#jim avis#pohutukawa#sehnsucht#sky burial#ukiyo-e#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

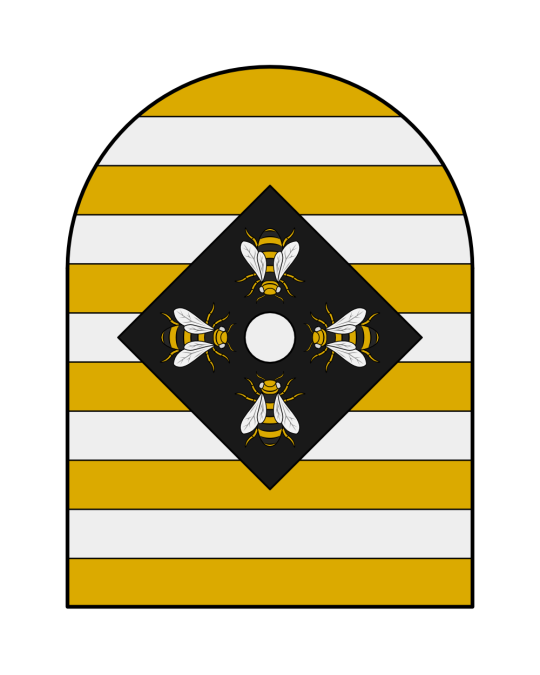

For Spooktober, a coat of arms for Telling the Bees

Blazon: Barruly of eleven Or and Argent, a lozenge Sable charged with four bees proper in cross facing in center a roundel Argent

Telling the bees is a tradition where hives are told of the keeper's important events. As part of funerals the bees are given a piece of funeral biscuit and told of the name of the deceased. If the bees were not "put into mourning" then it was believed such as the bees might leave their hive, sicken or die.

Here the shield shape and horizontal banding represent old wicker beehives, while the the black diamond is a funerary hatchment and the circle a funeral biscuit.

1 note

·

View note

Quote

How often I have wanted to kill those handsome boys who annoyed me because I didn't have enough cocks to ream them all at one time, not enough sperm to cram them with! A pistol shot would, I feel, have calmed my desire-ridden, jealousy-ridden heart and body.

Jean Genet, Funeral Rites

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your Galahkar Culture Masterpost is fantastic! I loved rereading all your fascinating lore ideas and it gave me so many questions. I will limit myself to three. ^_^ First, we know the water clans have rivalry? Do the smithing clans? Two, how did orange get the meaning of secrets? I’m sure there is a story. And third, what happens for funerals and weddings for people with no clan, or are the last of their clan, or their clan head is on a different island/separated by war? Thanks so much for sharing all your lovely ideas.

Thank you! I don't think I caught all the posts, but those are the big (and some small) ones. Took a bit to dig through them all.

You always ask such wonderful questions.

First:

Yes, the smithing Clans have a rivalry. Just not as extreme as some water clans. Clans Pontos and Najad have a feud because Clan Pontos accidentally destroyed one of the Najad's fishing grounds and refused to compensate for it.

Clans Utris and Gohlann are smithing Clans, but they have different specialities. The Gohlanns do the rougher work, the large pieces and things you need for building houses and so on. The Utris do the finer work. Household items, weapons and other small things. So their rivalry is more along the lines of "stay in your own lane" and "if you had done your job properly" and less "I'm going to murder you when I see you".

Two:

Red, yellow and orange are all associated with fire to certain degrees. They all take different aspects of it.

Red is the burning passion and destructive power, yellow the warmth of the hearth and orange the secrets whispered to the flames. As for why historically and context? As soon as I figure that out, I could propably write a dissertation about it. XD

Third:

People without a Clan are one of the very few exceptions where friends can build the pyre and be part of burning th body. They still get full funeral rites despite being Nameless since they still lived thier lives as Galahkari.

Normally, if the Clan is too small to handle a funeral, the family does it, blood and chosen family included. For Nyx that would include Libertus, Crowe and Ladone.

If it's the Clan Head who died, the chosen heir prepares the body. If the Clan is too small (like the Ulrics) then an Ostium will do the task. It's their task to make sure people get proper burials, so even if the Clan Head might be unable to come for whatever reason, the dead person still gets a proper funeral.

#ask#awlwren#ffxv#galahd#galahdian culture#galahdian religion#galahdian clans#clan rivalries#clan feuds#smithing clans#clan gohlann#clan utris#meaning of colours#funeral rites#galahdian funerals#geist answers

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

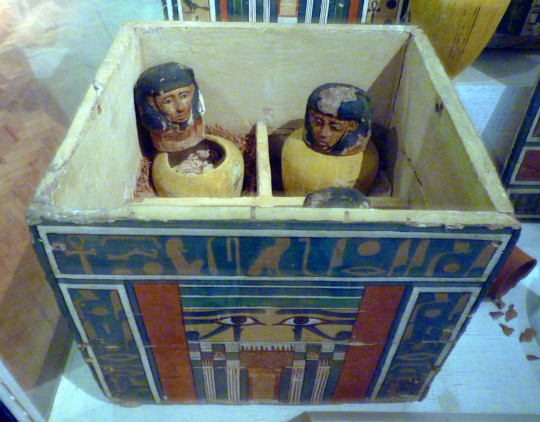

Today’s Flickr photo with the most hits: the canopic jar chest from the Tomb of the Two Brothers, in the Manchester Museum.

#ancient egypt#archaeology#manchester museum#manchester#tomb of the two brothers#canopic jar#canopic chest#entrails#burial#mummification#funeral rites#tomb#egypt

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

We did the rites for him, sang his deeds of war, set his name in the record of men who lived.

Circe, Madeline Miller, page 237

#studyblr#book quotes#circe#circe book#madeline miller#bookblr#quote#quotes#death#greek mythology#greek funeral rites#funeral rites

6 notes

·

View notes