#first solo nonstop transatlantic flight

Text

On this date in 1932 Amelia Earhart becomes the first woman to make a solo nonstop transatlantic flight. A trailblazer she was.

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

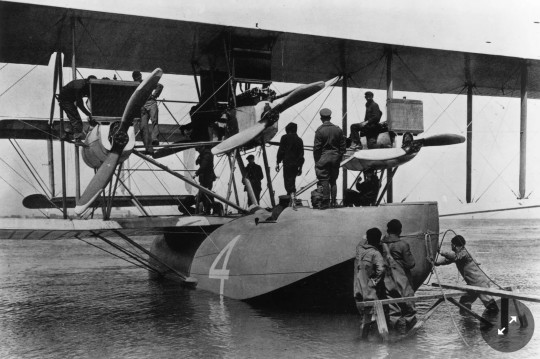

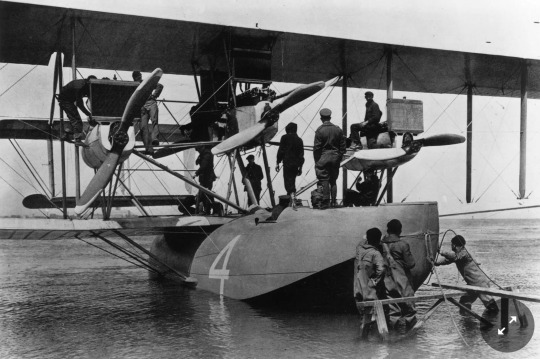

This Day in History: The First Transatlantic Flight

On this day in 1919, a U.S. Navy seaplane lands in Lisbon, Portugal, completing the very first transatlantic flight. Charles Lindbergh’s record-breaking flight was still nearly a decade in the future.

You’ve doubtless heard of Lindbergh’s feat, but you most likely haven’t heard of this Navy flight. Lindbergh’s trip might have been solo and nonstop, but it wasn’t the first trip across the Atlantic.

That first flight was completed by a crew of six Navy and Coast Guard pilots. They made the trip in a huge “flying boat”: the NC-4. That plane would look odd to modern eyes. Its appearance has been described as a “mash-up of the Wright brothers’ Kitty Hawk [plane] and a ship.”

NC-4 was one of four NC (Navy-Curtiss) flying-boats that had been built for a trip such as this one. Originally, all four planes were supposed to go together across the ocean, but NC-2 was ultimately used for parts and left behind. Together, the other three NCs would make the attempt.

Interestingly, London’s Daily Mail was then offering a cash prize to the first private flier to make the transatlantic crossing. As members of the military, the Navy and Coast Guard pilots aboard the NC flying boats were not eligible for that prize.

The three flying boats departed from the Rockaway Naval Air Station in Queens on May 8, 1919. The story continues here: https://www.taraross.com/post/tdih-first-transatlantic

#tdih#otd#on this day in history#history#aviation history#aviation#history blog#America#pioneers#sharethehistory

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

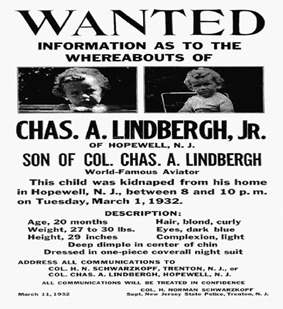

The Lindbergh Kidnapping and the Federal Kidnapping Act

By Emma Babashak, Columbia University, Class of 2024

July 10, 2023

On March 1st, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr., who was just 20 months old, was kidnapped from his nursery. He was the son Charles Lindbergh, who had famously made the first nonstop flight from New York to Paris and first solo transatlantic flight in 1927.

Law enforcement agencies, led by the New Jersey State Police, embarked on a relentless investigation to locate the abducted child and bring the perpetrators to justice. The Lindbergh kidnapping case marked the first time that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) became involved in a major criminal investigation. Under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI provided critical forensic expertise and resources. While this case had a tragic outcome (the child’s remains discovered accidentally on May 1932), it resulted in both public interest and legal change.[1]

As a result of this case, U.S. Congress enacted a federal kidnapping statute known as the Federal Kidnapping Act (also referred to as the Lindbergh Law). This law was created with the aim to allow federal authorities to pursue kidnappers even when the kidnappers had crossed state lines with their victims. [2]

The rationale behind creating such a law was rooted in the opinion that both state and local law enforcement agencies did not have the jurisdiction or resources to be able to pursue kidnappers who had escaped across a state line. With this new law, national law enforcement authorities, such as the FBI and U.S. Marshals, now had the power to intervene and aid the local law enforcement. In this way, the efficiency and effectiveness of kidnapping investigations would be enhanced.

The enactment of the law took place in 1932, but it was later amended in 1934 to include an exception for parents who abduct their own minor children. Furthermore, the amendment initially allowed for the possibility of imposing the death penalty in cases where the victim was not released unharmed.[3]

Only one person has been executed for a federal kidnapping conviction when the victim survived. Arthur Gooch was executed in 1936 after kidnapping police officers R. N. Baker and H.R. Marks in Texas. Although Gooch eventually released both victims alive in Oklahoma, the crime he committed was raised to a capital offense. This is because Baker sustained severe injuries after being forcefully pushed into a glass case that subsequently shattered.[4]

In response to this new law, several states enacted their own respective versions of the law, often coined as “Little Lindbergh Laws”, to handle cases of kidnapping within state boundaries. In certain states, for instance, if the victim suffered any physical harm, the crime qualified for capital punishment.

Because of the Supreme Court Case United States v. Jackson, kidnapping alone could no longer constitute a capital offense. In this case, the Supreme Court addressed the “death-qualification” provision in the Federal Kidnapping Act. This provision allowed for the exclusion of potential jurors from kidnapping cases if they had moral objections to the death penalty. The defendants in this case argued that this provision resulted in a biased jury that was more prone to conviction. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the defendants with the belief that this provision was unconstitutional because it resulted in a distinct class of jurors. Defendants facing only federal kidnapping charges could no longer be subject to the death penalty. Under the existing statute, the crime must result in the death of the victim in order to qualify as a capital offense.[5] All in all, the abduction of Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr led to the enaction of a federal law that is still in existence today.

______________________________________________________________

Emma Babashak is currently a rising senior attending Columbia University. She is majoring in Operations Research - Engineering Management Systems and minoring in both Economics and Psychology.

______________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/lindbergh-kidnapping

[2]https://www.mnhs.org/lindbergh/learn/kidnapping#:~:text=The%20Lindbergh%20kidnapping%20case%20led,pursue%20kidnappers%20across%20state%20jurisdictions.

[3] https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1726&context=lcp

[4] https://seoklaw.com/legal-news/the-little-lindbergh-law-and-the-story-of-oklahoman-arthur-gooch/

[5] https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/390/570/

0 notes

Text

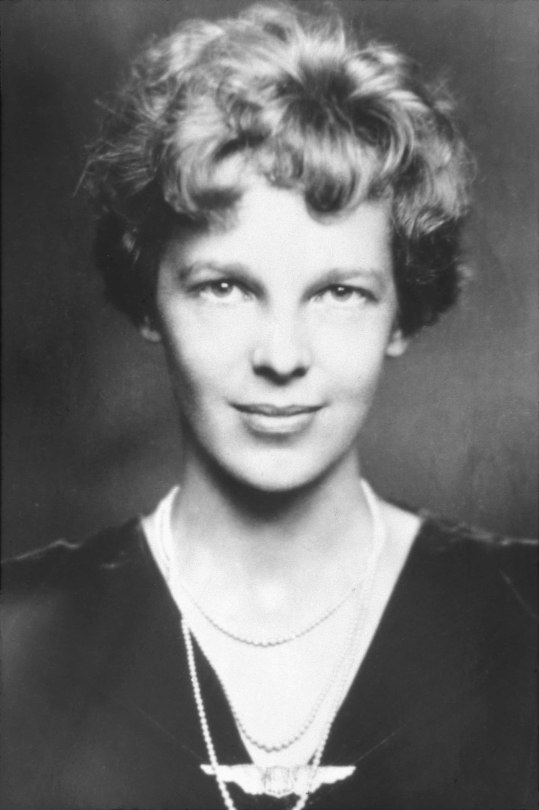

Amelia Earhart - First Woman to Fly Alone

Amelia Earhart - First Woman to Fly Alone

Amelia Earhart, whose full name is Amelia Mary Earhart, was the very first woman to fly alone across the Atlantic Ocean. She was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas, and disappeared on July 2, 1937, around Howland Island in the central Pacific Ocean. Her disappearance in 1937 while on a flight across the globe became a persistent mystery and the subject of considerable conjecture.

Early years

Her mother was from a wealthy family, and her dad was a railroad lawyer. Earhart showed early signs of her independent spirit and sense of adventure, traits for which she'd later become famous. Her father's alcoholism and the family's subsequent financial difficulties followed the passing of her grandparents.

Since the Earhart family relocated frequently, Amelia finished high school in Chicago in 1916. Following her mother's inheritance, Earhart became able to enroll at the Rydal, Pennsylvania, Ogontz School. Amelia, however, became interested in treating World War I combatants while visiting her sister in Canada. She quit junior college in 1918 to work as a nurse's assistant in Toronto.

Flights in the past

After the war, Earhart enrolled in Columbia University in New York City's pre-med program, but she departed in 1920 at her parents' urging to stay with them in California. She made her first flight there in 1920, which motivated her to sign up for flying lessons. When she accepted a position as a social worker at the Denison Home, a Boston settlement house for newcomers, Earhart moved to Massachusetts in the middle of the 1920s. She continued to pursue her love of flight.

Around this time, organizers were looking for a woman pilot to cross the Atlantic, and Earhart was selected in April 1928. Some hypothesized that Charles Lindbergh's resemblance, who had made the first nonstop solo transatlantic flight the previous year, may have had some bearing on the decision. Amelia Earhart gained worldwide recognition after landing in Burry Port, Wales, around June 18. She traveled the nation giving lectures and wrote a book on the flight called 20 Hours, 40 Minutes in 1928.

The majority of the publicity was handled by publisher George Palmer Putnam, who had already contributed to the historic flight's planning. When the couple got married in 1931, Earhart kept using their maiden names for her professional career.

On May 20–21, 1932, Amelia Earhart set sail alone towards the Atlantic Ocean, intending to live up to the fame her flight in 1928 had brought her. She was unable to reach Paris on time because of significant mechanical problems and poor weather. She wrote about her life and passion for flying in the book The Fun of It, which she eventually published. Then, Earhart conducted several flights across the nation.

Amelia Earhart is recognized for inspiring women to overcome constrictive social norms and explore a range of opportunities, particularly in the aviation business, in addition to her flying feats. The Ninety-Nines, a group of female pilots, was founded in 1929, and she was one of its original members.

When Earhart accomplished the first solo flight across Hawaii to California in 1935, she made aviation history. She left Honolulu around January 11 and arrived in Oakland the following day after a 17-hour, 7-minute journey. Later that year, when she flew by herself from Los Angeles to Mexico City, she created history.

Final Takeoff and Disappearance

With Fred Noonan serving as her navigator, Amelia Earhart set out on a twin-engine Lockheed Electra journey around the globe in 1937. The two set out from Miami on June 1 for their 29,000-mile (47,000-km) voyage east. Before arriving in Lae, New Guinea, on June 29, they made several refueling stops during the ensuing weeks. Earhart & Noonan had covered about 22,000 miles by that point (35,000 km).

On July 2, they set off in the direction of Howland Island, which was some 2,600 miles (4,200 kilometers) distant. It was anticipated that the trip would be challenging, especially given how challenging it was to find the tiny coral atoll. Two well-lit U.S. ships were positioned along the route to aid with navigation.

Additionally, Earhart had sporadic radio communications with the Itasca, a Coast Guard vessel nearby Howland. Earhart radioed at the end of the flight that the plane was out of fuel. She declared, "We are running north and south," about an hour later.

The Itasca only ever received one more transmission after that. It was assumed that the plane had crashed around 100 miles (160 km) from the island, therefore a thorough search was conducted to look for Earhart and Noonan. However, the effort was abandoned on July 19, 1937, and the two were listed as lost at sea.

0 notes

Text

Dhaka To Sylhet Flight

Ultimate Guide to Finding Cheap Flights to Sylhet

A trip's most expensive component is usually the airfare. Despite recent decreases in transatlantic flight prices, transatlantic flights can still severely impact travel budgets. Finding a cheap flight deal can make or break a trip, whether you're a solo traveler on a budget or a family looking for a vacation abroad. You can find cheap flights to Sylhet if you know where to look. You can find cheap Dhaka to Sylhet flight wherever you are by following these tips:

Choose Dates And Destinations Based On Price

There is a great deal of variation in airline ticket prices based on the week of the year, the time of year, and upcoming holidays. Travel is prevalent in August. Everyone wants to go somewhere warm when the kids are out of school in the summer. Flying when everyone else is flying will increase the cost of your ticket. Dates should be flexible.

Book Your Flights First And Keep Your Plans Flexible

Travel planning follows this script: Pick a spot, plan your dates, book your flights, and go. Unfortunately, it costs you money to go through that process. It is easy to lose hundreds of dollars when you set your travel dates before booking flights. Breaking this habit is time-consuming. The Flight First Rule can help you accomplish this.

Book indirect flight

Say it with us again: Flexibility is critical. And when you're trying to score significant savings, it can go beyond shifting your dates and destinations. Being flexible with your route can help you save even more. Of course, you want to fly nonstop as much as possible. And while it may seem counter-intuitive, sometimes taking an extra stop on the way to your final destination can pay off with significant savings that it's worth it – especially if you're crossing an ocean.

Use Search Engines To Compare Flights

It would help if you compared prices from different airlines to find the cheapest flights. The best way to do that is by using a flight search engine. When using a flight search engine, enter the airports of your departure and arrival cities. You will receive a list of cheap tickets with all the necessary details.

0 notes

Text

On this day in 1919, a U.S. Navy seaplane lands in Lisbon, Portugal, completing the very first transatlantic flight. Charles Lindbergh’s record-breaking flight was still nearly a decade in the future.

You’ve doubtless heard of Lindbergh’s feat, but you most likely haven’t heard of this Navy flight. Lindbergh’s trip might have been solo and nonstop, but it wasn’t the first trip across the Atlantic.

That first flight was completed by a crew of six Navy and Coast Guard pilots. They made the trip in a huge “flying boat”: the NC-4. That plane would look odd to modern eyes. Its appearance has been described as a “mash-up of the Wright brothers’ Kitty Hawk [plane] and a ship.”

NC-4 was one of four NC (Navy-Curtiss) flying-boats that had been built for a trip such as this one. Originally, all four planes were supposed to go together across the ocean, but NC-2 was ultimately used for parts and left behind. Together, the other three NCs would make the attempt.

Interestingly, London’s Daily Mail was then offering a cash prize to the first private flier to make the transatlantic crossing. As members of the military, the Navy and Coast Guard pilots aboard the NC flying boats were not eligible for that prize.

The three flying boats departed from the Rockaway Naval Air Station in Queens on May 8, 1919. NC-1 and NC-3 arrived at the first stop in Nova Scotia without incident, but the NC-4 pilots ran into trouble. Two of the plane’s four engines developed problems. The seaplane was forced into the water. It taxied until it reached the port at Chatham, Massachusetts.

Mechanics in Massachusetts soon got the engines working again, but NC-4 was delayed for several days. Fortunately, it caught up with the other two planes at Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland, where NC-1 and NC-3 had been delayed by bad weather. Thus, the three planes would undertake the next leg of the trip together: They were to travel nearly 1,400 miles to the Azores Islands in the Atlantic.

All three planes departed late on May 16, but NC-3 immediately ran into trouble. It was too heavy and couldn’t take off. Much to his chagrin, one crew member was left behind. With its load lightened, NC-3’s second attempt to take off worked.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the end of NC-3’s troubles. As the planes approached the Azores, both NC-3 and NC-1 got lost in dense fog. Attempts to contact Navy destroyers stationed below failed, so the flying boats landed in rough seas instead. The crews were safe, but the planes were too damaged to continue.

NC-4 was the only plane left. The crew landed the plane successfully at Horta, in the middle of the Azores. They hadn’t quite made it to Ponta Delgada, the planned landing spot, but they’d gotten pretty close.

Weather caused an additional delay before the quick flight to Ponta Delgada was finally accomplished three days later. The rest of the trip was uneventful, and NC-4 landed in Lisbon on May 27.

Two private aviators would win the Daily Mail’s cash prize a few weeks later, but our Navy and Coast Guard pilots accomplished the feat first. Today, those pilots have been largely forgotten, but the feat stunned the world in 1919.

Imagine being the very first to fly across the Atlantic Ocean—and doing it in something that looked like a bulky boat with wings attached.

“I had a better chance of reaching Europe in the Spirit of St. Louis than the NC boats had of reaching the Azores,” Lindberg later marveled. “I had a more reliable type of engine, improved instruments and a continent instead of an island for a target. It was skill, determination and a hard-working crew that carried the NC-4 to the completion of the first transatlantic flight.”

---------------------------

If you enjoy these history posts, please see my note below. :)

Gentle reminder: History posts are copyright © 2013-2022 by Tara Ross. I appreciate it when you use the shar e feature instead of cutting/pasting.

#TDIH #OTD #AmericanHistory #USHistory #liberty #freedom #ShareTheHistory

0 notes

Photo

At 7:52 on May 20, 1927, Charles Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field in Long Island, New York, on the world’s first solo non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean.

He touched down at Le Bourget Field in Paris at 22:22 the next day.

#Charles Lindbergh#take off#Spirit of St. Louis#airplane#20 May 1927#USA#anniversary#US history#National Air and Space Museum#Washington DC#summer 2009#original photography#Smithsonian Institution#free admission#travel#vacation#indoors#Ryan NYP#N-X-211#first solo nonstop transatlantic flight#Ryan Airlines#Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OnThisDay in 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh completed the first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight and the first ever nonstop flight between New York to Paris on The Spirit of St. Louis

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amelia Earhart (1897-1937).

American aviation pioneer and author.

.

Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many other records, wrote best-selling books about her flying experiences, and was instrumental in the formation of The Ninety-Nines, an organization for female pilots. Her disappearance during a flight around the world in 1937 became an enduring mystery, fueling much speculation.

.

During a visit to her sister in Canada, Amelia developed an interest in caring for soldiers wounded in World War I. In 1918 she left junior college to become a nurse’s aide in Toronto.

.

She went on her first airplane ride in New York City in 1920, an experience that prompted her to take flying lessons. In 1921 she bought her first plane, a Kinner Airster, and two years later she earned her pilot’s license. In the mid-1920s Earhart moved to Massachusetts, where she became a social worker at the Denison House, a settlement home for immigrants in Boston. She also continued to pursue her interest in aviation.

.

In 1928, Earhart became the first female passenger to cross the Atlantic by airplane (accompanying pilot Wilmer Stultz), for which she achieved celebrity status. In 1932, piloting a Lockheed Vega 5B, Earhart made a nonstop solo transatlantic flight, becoming the first woman to achieve such a feat. She received the United States Distinguished Flying Cross for this accomplishment.

.

In addition to her piloting feats, Earhart was known for encouraging women to reject constrictive social norms and to pursue various opportunities, especially in the field of aviation.

In 1935, Earhart became a visiting faculty member at Purdue University as an advisor to aeronautical engineering and a career counselor to women students. She was also a member of the National Woman's Party and an early supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment.

.

During an attempt to make a circumnavigational flight of the globe in 1937 in a Purdue-funded Lockheed Model 10-E Electra, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan disappeared over the central Pacific Ocean near Howland Island.

.

She was married to George P. Putnam.

[Submission]

#amelia earhart#aviator#aviation#early 20th century#ww1#world war 1#1920s#1930s#american history#us history#usa#women history#women in history#history#history lesson#historical#historic#história#histoire#history buff#history crush#history hottie#history lover#history nerd#history geek#historical babes#historical hottie#historical figure#badass woman#heroine

256 notes

·

View notes

Photo

May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh lands in Paris’ Le Bourget Field, completes the world’s first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight [1023x897] Check this blog!

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Arrivals & Departures

born 24 July 1897 – disappeared 02 July 1937, declared dead 05 January 1939

Amelia Mary Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart (/ˈɛərhɑːrt/, born 24 July 1897 – disappeared 02 July 1937, declared dead 05 January 1939) was an American aviation pioneer and author. Earhart was the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. She set many other records, wrote best-selling books about her flying experiences, and was instrumental in the formation of The Ninety-Nines, an organization for female pilots.

Born in Atchison, Kansas, Earhart developed a passion for adventure at a young age, steadily gaining flying experience from her twenties. In 1928, Earhart became the first female passenger to cross the Atlantic by airplane (accompanying pilot Wilmer Stultz), for which she achieved celebrity status. In 1932, piloting a Lockheed Vega 5B, Earhart made a nonstop solo transatlantic flight, becoming the first woman to achieve such a feat. She received the United States Distinguished Flying Cross for this accomplishment. In 1935, Earhart became a visiting faculty member at Purdue University as an advisor to aeronautical engineering and a career counselor to women students. She was also a member of the National Woman's Party and an early supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment.

During an attempt to make a circumnavigational flight of the globe in 1937 in a Purdue-funded Lockheed Model 10-E Electra, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan disappeared over the central Pacific Ocean near Howland Island.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh Landed in Paris, Completing the World’s First Solo, Nonstop Transatlantic Flight https://ift.tt/2LK7y8v

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Spirit of St. Louis Plane Also From My Clients Highschool Logo Quick History Lesson The Spirit of St. Louis is the custom-built, single-engine, single-seat, high-wing monoplane that was flown by Charles Lindbergh on May 20–21, 1927, on the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight from Long Island, New York, to Paris, France, for which Lindbergh won the $25,000 Orteig Prize. I Love The Way It Came Out Perfect #Silhouette ! BOOK YOUR APPT. NOW CASHAPP Deposit $Acetruefreak #Acetruefreak #aceinktattoodeliveryservice #plane #spiritofstlouis #tattooed #tattoo #tattoos #inked #ink #tattooartist #tattooart #art #tattoolife #love #tattooing #tattooer #instatattoo #flawless #tattoostyle #inkedup #bodyart #tattooink #tattoodesign #me #instagood #artist #tattoomodel #blackwork #tattooideas (at St. Louis, Missouri) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9BI9yNBx4R/?igshid=168tek7hllhgb

#silhouette#acetruefreak#aceinktattoodeliveryservice#plane#spiritofstlouis#tattooed#tattoo#tattoos#inked#ink#tattooartist#tattooart#art#tattoolife#love#tattooing#tattooer#instatattoo#flawless#tattoostyle#inkedup#bodyart#tattooink#tattoodesign#me#instagood#artist#tattoomodel#blackwork#tattooideas

0 notes

Photo

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. At age 25 in 1927, he went from obscurity as a U.S. Air Mail pilot to instantaneous world fame by winning the Orteig Prize for making a nonstop flight from New York to Paris. Lindbergh covered the 33 1⁄2-hour, 3,600-statute-mile (5,800 km) flight alone in a single-engine purpose-built Ryan monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis. This was the first solo transatlantic flight. A unique, fashionable, lined notebook with modern and amazing Charles Lindbergh cover. ⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️⚜️⬇️ https://www.amazon.com/Charles-Lindbergh-notebook-achieve-Notebooks/dp/1699235481/ref=mp_s_a_1_1?keywords=lucanus+lindbergh&qid=1577644246&sr=8-1 ⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️⚜️⬆️ #charleslindbergh #lindberg #flight #lucanus #notebook #independent #publisher #amazon #book #note #journal #inspiration #writing #gift #giftideas #amazing #biography #famous #people https://www.instagram.com/p/B6qqS-0H8lO/?igshid=1k3t60xi1x0fk

#charleslindbergh#lindberg#flight#lucanus#notebook#independent#publisher#amazon#book#note#journal#inspiration#writing#gift#giftideas#amazing#biography#famous#people

0 notes

Photo

Our Lady of Loreto and Lone Eagle

On May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh completed a nonstop solo transatlantic flight from New York to Paris in 33 hours and 32 minutes. During the time when he was isolated from the rest of the world, he tells us in his memoirs, he prayed. He prayed throughout the voyage and the more his anxiety increased the more he prayed. The New York Times wrote of him: "The more one thinks of the behavior of Lindbergh in Paris, so much the more one arrives at the conclusion that God had a great part in the success of the aviator."

Probably the confidence which sustained the young American aviator throughout his flight was due to a small image of Our Lady of Loreto, proclaimed 7 years previously by Pope Benedict XV, as Patroness of air travelers. Lindbergh had brought the medal on board his plane "The Spirit of St. Louis" before his departure. It was a gift from Father Hussman, pastor of St. Enrico's in St. Louis. Lindbergh accepted the medal with joy and promised to return it as soon as he arrived at his destination, but Father Hussman preferred to leave the blessed medal with the young man known as the Lone Eagle.

The medal was the first to travel across the Atlantic by air and the medal literally saved the young pilot's life. He tells us in his memoirs that he had the medal hung in the cabin of his plane and it was the gentle tapping of this medal against the wall of the cabin which awoke him when he fell asleep.

“Some people are so foolish that they think they can go through life without the help of the Blessed Mother. Love the Madonna and pray the rosary, for her Rosary is the weapon against the evils of the world today. All graces given by God pass through the Blessed Mother.” -St. Padre Pio

0 notes

Photo

August 26, 1974

Charles Lindbergh, the first man to accomplish a solo nonstop flight across the Atlantic Ocean, dies in Maui, Hawaii, at the age of 72.

Charles Augustus Lindbergh, born in Detroit in 1902, took up flying at the age of 20. In 1923, he bought a surplus World War I Curtiss “Jenny” biplane and toured the country as a barnstorming stunt flyer. In 1924, he enrolled in the Army Air Service flying school in Texas and graduated at the top of his class as a first lieutenant. He became an airmail pilot in 1926 and pioneered the route between St. Louis and Chicago. Among U.S. aviators, he was highly regarded.

In May 1919, the first transatlantic flight was made by a U.S. hydroplane that flew from New York to Plymouth, England, via Newfoundland, the Azores Islands, and Lisbon. Later that month, Frenchman Raymond Orteig, an owner of hotels in New York, put up a purse of $25,000 to the first aviator or aviators to fly nonstop from Paris to New York or New York to Paris. In June 1919, the British fliers John W. Alcock and Arthur W. Brown made the first nonstop transatlantic flight, flying 1,960 miles from Newfoundland to Ireland. The flight from New York to Paris would be nearly twice that distance.

Orteig said his challenge would be good for five years. In 1926, with no one having attempted the flight, Orteig made the offer again. By this time, aircraft technology had advanced to a point where a few people did believe such a flight might be possible. Several of the world’s top aviators—including American polar explorer Richard Byrd and French flying ace Rene Fonck—decided to accept the challenge, and so did Charles Lindbergh.

Lindbergh convinced the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce to sponsor the flight, and a budget of $15,000 was set. The Ryan Airlines Corporation of San Diego volunteered to build a single-engine aircraft to his specifications. Extra fuel tanks were added, and the wing span was increased to 46 feet to accommodate the additional weight. The main fuel tank was placed in front of the cockpit because it would be safest there in the event of a crash. This meant Lindbergh would have no forward vision, so a periscope was added. To reduce weight, everything that was not utterly essential was left out. There would be no radio, gas gauge, night-flying lights, navigation equipment, or parachute. Lindbergh would sit in a light seat made of wicker. Unlike other aviators attempting the flight, Lindbergh would be alone, with no navigator or co-pilot.

The aircraft was christened The Spirit of St. Louis, and on May 12, 1927, Lindbergh flew it from San Diego to New York, setting a new record for the fastest transcontinental flight. Bad weather delayed Lindbergh’s transatlantic attempt for a week. On the night of May 19, nerves and a newspaperman’s noisy poker game kept him up all night. Early the next morning, though he hadn’t slept, the skies were clear, and he rushed to Roosevelt Field on Long Island. Six men had died attempting the long and dangerous flight he was about to take.

At 7:52 a.m. EST on May 20, The Spirit of St. Louis lifted off from Roosevelt Field, so loaded with fuel that it barely cleared the telephone wires at the end of the runway. Lindbergh traveled northeast up the coast. After only four hours, he felt tired and flew within 10 feet of the water to keep his mind clear. As night fell, the aircraft left the coast of Newfoundland and set off across the Atlantic. At about 2 a.m. on May 21, Lindbergh passed the halfway mark, and an hour later dawn came. Soon after, The Spirit of St. Louis entered a fog, and Lindbergh struggled to stay awake, holding his eyelids open with his fingers and hallucinating that ghosts were passing through the cockpit.

After 24 hours in the air, he felt a little more awake and spotted fishing boats in the water. At about 11 a.m. (3 p.m. local time), he saw the coast of Ireland. Despite using only rudimentary navigation, he was two hours ahead of schedule and only three miles off course. He flew past England and by 3 p.m. EST was flying over France. It was 8 p.m. in France, and night was falling.

At the Le Bourget Aerodrome in Paris, tens of thousands of Saturday night revelers had gathered to await Lindbergh’s arrival. At 10:24 a.m. local time, his gray and white monoplane slipped out of the darkness and made a perfect landing in the air field. The crowd surged on The Spirit of St. Louis, and Lindbergh, weary from his 33 1/2-hour, 3,600-mile journey, was cheered and lifted above their heads. He hadn’t slept for 55 hours. Two French aviators saved Lindbergh from the boisterous crowd, whisking him away in an automobile. He was an immediate international celebrity.

President Calvin Coolidge dispatched a warship to take the hero home, and “Lucky Lindy” was given a ticker-tape parade in New York and presented with the Congressional Medal of Honor. His place in history, however, was not complete.

In 1932, he was the subject of international headlines again when his infant son, Charles Jr., was kidnapped, unsuccessfully ransomed, and then found murdered in the woods near the Lindbergh home. German-born Bruno Richard Hauptmann was convicted of the crime in a controversial trial and then executed.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Lindbergh became a spokesperson for U.S. isolationism and was sharply criticized for his apparent Nazi sympathies and anti-Semitic views. After the outbreak of World War II, the fallen hero traveled to the Pacific as a military observer and eventually flew more than two dozen combat missions, including one in which he downed a Japanese aircraft. Lindbergh’s wartime service largely restored public faith in him, and for many years he worked with the U.S. government on aviation issues. In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him brigadier general in the Air Force Reserve. He died in Hawaii in 1974.

1 note

·

View note