#european folklore

Text

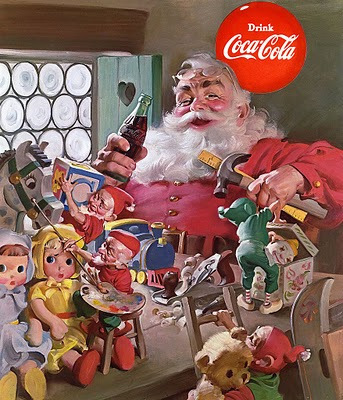

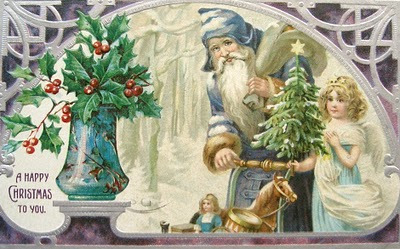

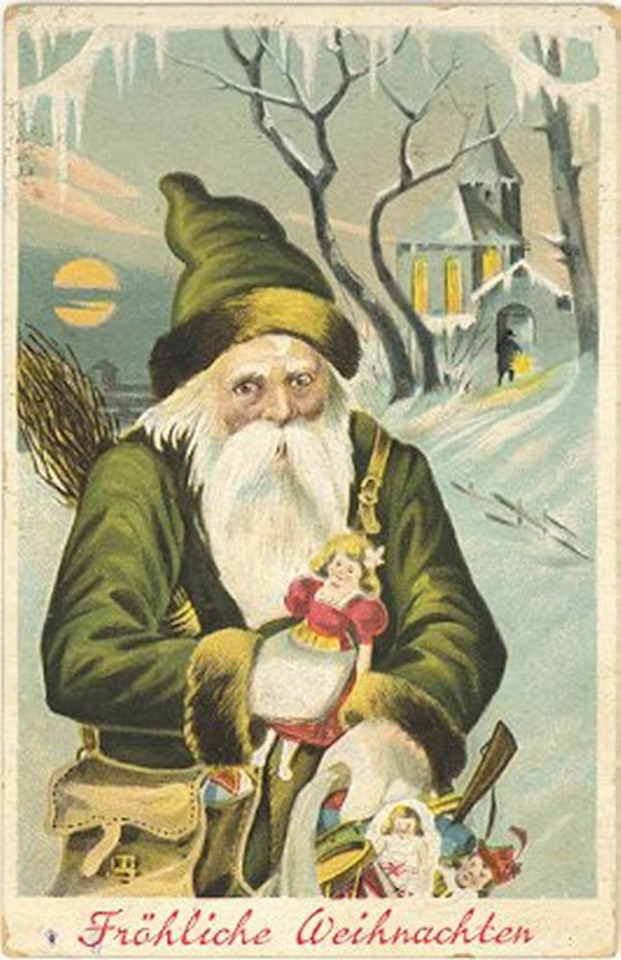

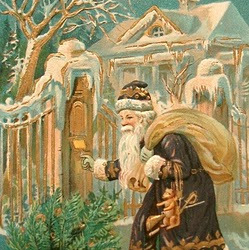

I evoked before how Père Noël's incarnations varied between a "drab" version in brown or dark clothes ; and a more colorful one of varying colors. But this isn't just something specific to France.

Today all the incarnations of the Christmas "gift-giver" are associated with the color red, thanks to the mass-spreading of the American Santa Claus, who himself became exclusively associated with red thanks to the Coca-Cola advertisement campaign that solidified the modern appearance of Santa in people's minds.

However, before this Coca-Cola Santa appeared - before the American Santa even existed - the figure of "Father Christmas" wore numerous cloaks and coats of varying colors, a tradition that is still maintained today in Europe. Be it in France, in England or in Germany, the Father Christmas of the 19th century usually wore green or blue - but other colors were possible. You've got brown, purple and white ones...

And the immense variety of colors is perfectly reflected by this collection of chromos of the end of the 19th century which shows the same Father Christmas/Père Noël with coats of various colors:

#christmas#santa claus#father christmas#christmas lore#père noël#colors#the fashion of santa#european folklore

423 notes

·

View notes

Text

A path in Anoia (Penedès, Catalonia), with part of the Montserrat mountain range in front.

Montserrat is located right at the centre of Catalonia and for centuries has been considered its spiritual and religious heart. The weird shapes of the mountains (in the Catalan language, "Mont serrat" means "sawed mountain") have created many legends.

One of this legends says that each vertical shape in the mountain range was once a fierce giant warrior. As is common with legends, the story mixes real events (the Arab conquest of 711, the later conquest of the Catalan counts, the loss of Catalonia's statehood) with fantasy elements. Here's the legend:

When the Arabs invaded the Iberian Peninsula, their army brought giants to help them. These giants were so strong, that they could stomp on the local Catalans and if they were flies, and so it was easy for the Arabs to occupy most of Catalonia, with only the north remaining out of their reach. Some centuries later, Catalonia managed to invade southwards again. When the Arab rulers were expelled, the giants turned into stone, becoming the Montserrat mountain range.

But they didn't just die when they were petrified, there was one occasion where they could still move: every time a King of Catalonia got married, the giants came back to life and danced to celebrate it. When they were done, they turned back to stone, in a different position to before, thus changing the mountain's shape.

However, with time, royal marriages and wars, Catalonia lost its king, and became ruled by a foreign (Spanish) king. Since then, the mountain has no reason to celebrate and has not moved again. In the area, it is said that when Catalonia once again has a king, the mountains will come back to life and defend the land.

Photo from Visit Anoia. A source for the legend can be found here.

#llegendes#montserrat#catalunya#fotografia#natura#myths and legends#mythology#travel#travel photography#landscape#nature#landscape photography#mountains#hiking#europe#catalonia#giants#myths#european folklore

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zitiron- a creature with the bottom half of a fish and the top half of a knight.

The zitiron only shows up in three sources that I can find- the Ortus Sanitatis (published in Germany 1491, author unknown), Van der Naturen Bloeme (early 14th c) by Flemish poet Jacob van Maerlant, and De natura rerum (1244 CE) by Flemish writer Thomas of Cantimpré. Van der Naturen Bloeme is actually just a Dutch translation of the Latin De natura rerum, so technically there's only two original sources. The only reason I mention both is that the original De natura rerum- which is sourced from a large number of works by philosophers and writers such as Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, St. Ambrose, Jacques de Vitry, and too many others to explore them all as original sources- doesn't have any illustrations and is in Latin, which I can't read, making it a personally useless source. But Van der Naturen Bloeme does have illustrations- the third image in this post is Jacob van Maerlant's interpretation of the zitiron I assume to be outlined in De natura rerum.

The only other original place that a zitiron can be found, according to the internet, is in the Ortus Sanitatis, a Latin natural history encyclopedia with no known author published in 1491 in Mainz, Germany. It has illustrations, the second image in this post is the author's interpretation. But again, I can't read Latin and it's hard to read the stylized text to put into google translate.

There is almost no information about the zitiron online, which is a shame because it's a really interesting figure. If you can read Latin or medieval Dutch I would LOVE to work together to place the origin of this mythological creature and learn more about it!

For the drawing, I wanted to honor Jacob van Maerlant and Thomas of Cantimpré's Flemish heritage. The helmet, chainmail, shield, and goedendag on the zitiron are representative of what the Flemish forces wore and used at the Battle of the Golden Spurs, a 1302 victory of the French that is a source of pride and celebrated every July 11th by the Flemish today.

TLDR: The zitiron is a little known creature from the Middle Ages or perhaps antiquity, with the bottom half of a fish and the top half of a knight. My drawing is inspired by the Flemish culture of two of the only writers to leave any information about the zitiron.

If you've got the time and can read Latin, could you take a look at the two Latin texts I mentioned? For the Ortus Sanitatis, I was able to flip through the whole thing and find the page that has the info on zitirons. It's on page 730 here- (x). But for De natura rerum, which you can access here (x), I have no idea where it could be. There's a translation project for it ongoing through Kalamazoo College, but I don't see anything relating to zitirons or relevant mythology on their page so far. And if you can miraculously read medieval Dutch, here's the link to the page on zitirons in Van der Naturen Bloeme (x).

#mermay#mermay 2023#long post#folklore#flemish folklore#european folklore#my art#zitiron#mermaid#thanks for reading this is a long one : )

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lou Carcolh from French folklore.

Its gaping mouth was surrounded by several long, hairy, and slime covered tentacles that could extend for miles. These appendages stretched out from the cave it inhabited for a long distance and laid upon the ground among its own viscous slime. They would ensnare and drag back to its anybody anything within reach. It would then swallow the victim whole with its gigantic mouth.

Fortunately, the Carcohl wasn’t a fan of daylight, passing most of its time resting in its underground lair, surfacing only to hunt.

Rumor has it a merchant once dared enter the Carcolh lair and stole some of its eggs. He took such eggs with him when traveling to the New World, but the eggs were lost or stolen before he arrived. Some say that one of those eggs floated all the way to Grenhaven, hatching near the dark hemlock hills that surround the port, explaining some local legends about a giant carnivore snail haunting a section of the forest called Leeds Hop.

The Carcohl hasn’t been seen in more than 50 years, which many think indicates the beast has died. Other, less optimistic, people, prefer to believe the beast is alive but in deep hibernation waiting for a mate.

Follow @mecthology for more legends and lores.

DM for pic credit.

Source: Wikipedia, cryptidzfandom.com, mythicalcreaturescatalogue.com

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untameable power. Their horns were believed to detect and act as an antidote for any poison, as well as cure disease.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#european folklore#european legend#unicorn#monster#beast

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Christmas Spider (Loremas post #1)

(This post is safe for Arachnophobes as no irl spiders or spider imagery will be displayed except for a fake ornament of one<3)

We are kicking off Loremas with one of the most adorable Christmas Legends I've had the pleasure of researching.

This legend originates from Eastern Europe, but is very prominent in Ukraine. The story goes as follows.

"A poor but hardworking family were struck by an incredible loss of the man of the household, leaving the mother to be a widow. However she managed to keep her children's spirits high even if their house wasn't in the best shape, their love for one another was stronger than steel.

One day, a pinecone fell through a hole in the ceiling and onto the dirt floor of the home. It had already took root by the time the kids noticed it, but they were beyond excited. They could finally have a Christmas Tree that year and their mother agreed to keep it.

However, when Christmas eve arrived, they couldn't afford decorations for it. The children and their mother went to bad, saddened that they didn't have one decoration for their lovely tree.

When they awoke that Christmas morning, they were astounded to see their tree adorned with cobwebs all over the branches. The sunlight hit the cobwebs, revealing shimmering colors of silver and gold. They had never seen such incredible decorations and wept for joy. That family was said to have been blessed and never went into poverty ever again."

The origins of this folk tale are unknown but it is believed to have come from either Germany or Ukraine. (Feel free to correct me if I'm wrong)

In Germany and Poland, it is believed to be good luck to find a spider or a spiders web on Christmas. Little spider like ornaments called Pavuchky are quite popular in Ukraine. They are usually made of paper and or wire. Artificial spider webs are also not unheard of for decorating the trees. Its believed this tale was also the origin of Tinsel being used.

How could it fit into the ROTG universe? It's quite simple! The Christmas spider could be a helper of North's. In charge of decorations for the workshop, or the North pole or for a family in need. North would keep the spider safe and happy in his workshop. Maybe he even made a pathway for it along the walls. It would be a cute addition to his team.

Hope you enjoyed this tale <3

#loremas#guardians of childhood#rise of the guardians#rotg#rotgoc#the christmas spider#folklore#european folklore#nicholas st north goc#nicholas st north rotg#nicholas st. north#nicholas st north#north rotg#rotg north#spiders#tw spiders#cw spiders#spider mention

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wrote an article about bunads for 17 mai tomorrow! check it out!

#would have drawn more but times up#like a vocab tthing with names in norwegian for all parts of the dress#might update it in the future#bunad#17 mai#norway#norge#norwegian#folk dress#folk costumes#traditional costumes#nordic#scandinavian#european folklore#nordic folklore#scandinavian folklore

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Yaga journal: Witches and demons of Eastern Europe

The next article I’ll translate from the issue (I won’t translate all of them since some are not very relevant for this blog) is “Baba Yaga, witches, and the ambiguous demons of oriental Europe” by Stamatis Zochios.

The article opens by praising the 1863′s “Reasoned dictionary of the living russian language”. by scholar, lexicograph and folklorist Vladimir Dahl, which is one of the first “systematic essays” that collects the linguistic treasures of Russia. By collecting more than thirty thousand proverbs and sayings, insisting on the popular and oral language, the Dictionary notably talked about various terms of Russian folklore; domovoi, rusalka, leshii... And when it reaches Baba Yaga, the Dictionary calls her : сказочное страшилищ (skazochnoe strashilishh) , that is to say “monster of fairytales”.But the article wonders about this denomination... Indeed, for many people (such as Bogatyrev) Baba Yaga, like other characters of Russian fairytales (Kochtcheï or Zmey Gorynych) do not exist in popular demonology, and is thus exclusively a character of fairy tales, in which she fulfills very specific functions (aggressor, donator if we take back Propp’s system). But the author of this article wonder if Baba Yaga can’t actually be found in “other folkloric genres” - maybe she is present in legends, in popular beliefs, in superstitions and incantations.

Baba Yaga, as depicted in the roleplaying game “Vampire: The Masquerade”

For example, in a 19th century book by Piotr Efimenko called “Material for ethnography of the Russian population of the Arkhangelsk province”, there is an incantation recorded about a man who wante to seduce/make a woman fall in love with him. During this incantation the man invokes the “demons that served Herod”, Sava, Koldun and Asaul and then - the incantation continues by talking about “three times nine girls” under an oak tree”, to which Baba Yaga brings light. The ritual is about burning wood with the light brought by Baba Yaga, so that the girl may “burn with love” in return. Efimenko also mentions another “old spell for love” that goes like this: “In the middle of the field there are 77 pans of red copper, and on each of them there are 77 Egi-Babas. Each 77 Egi-Babas have 77 daughters with each 77 staffs and 77 brooms. Me, servant of God (insert the man’s name here) beg the daughters of the Egi-Babas. I salute you, daughters of Egi-Babas, and make the servant of God (insert name of the girl here) fall inlove, and bring her to the servant of God (insert name of the man here).” The fact Baba Yaga appears in magical incantations proves that she doesn’t exist merely in fairytales, but was also part of the folk-religion alongside the leshii, rusalka, kikimora and domovoi. However two details have to be insisted upon.

One: the variation of the name Baba Yaga, as the plural “Egi-Babas”. The name Baba Yaga appears in numerous different languages. In Russian and Ukrainian we find Баба-Язя, Язя, Язі-баба, Гадра ; in Polish jędza, babojędza ; in Czech jezinka, Ježibaba meaning “witch, woman of the forest”, in Serbian баба jега ; in Slovanian jaga baba, ježi baba ... Baba is not a problem in itself. Baba, comes from the old Slavic баба and is a diminutive of бабушка (babyshka), “grand-mother” - which means all at the same time a “peasant woman”, “a midwife”, a (school mistress? the article is a bit unclear here), a “stone statue of a pagan deity”, and in general a woman, young or old. Of course, while the alternate meanings cannot be ignored, the main meaning for Baba Yaga’s name is “old woman”. Then comes “Yaga” and its variations, “Egi”, “Jedzi”, “Jedza”, which is more problematic. In Fasmer’s etymology dictionary, he thinks it comes from the proto-Slagic (j)ega, meaning “wrath” or “horror”. Most dictionaries take back this etymology, and consider it a mix of the term baba, старуха (staruha), “old woman”, and of яга, злая (zlaia), “evil, pain, torment, problem”. So it would mean злая женщина (zlaja zhenshhina), “the woman of evil”, “the tormenting woman”. However this interpretation of Yaga as “pain” is deemed restrictive by the author of this article.

Aleksandr Afanassiev, in his “Poetic concepts of the Slavs on nature”, proposed a different etymology coming from the anskrit “ahi”, meaning “snake”. Thus, Baba Yaga would be originally a snake-woman similar to the lamia and drangua of the Neo-hellenistic fairytales and Albanian beliefs. Slavic folklore seems to push towards this direction since sometimes Baba Yaga is the mother of three demon-like daughters (who sometimes can be princesses, with one marrying the hero), and of a son-snake that will be killed by the hero. Slovakian fairytales tale back the link with snakes, as they call the sons of Jezi-Baba “demon snakes”. On top of that, an incantation from the 18th century to banish snakes talks about Yaga Zmeia Bura (Yaga the brown snake): “I will send Yaga the brown snake after you. Yaga the brown snake will cover your wound with wool.” According to Polivka, “jaza” is a countryside term to talk about a mythical snake that humans never see, and that turns every seven years into a winged seven-headed serpent. With all that being said, it becomes clear (at least to the author of this article) that one of the versions of Yaga is the drakaina, the female dragon with human characteristics. These entities are usually depicted with the head and torso of women, but the lower body of a snake. They are a big feature of the mythologies of the Eurasian lands - in France the most famous example is Mélusine, the half-snake half-woman queen, whose story was recorded between the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th by Jean d’Arras (in his prose novel La Noble Histoire de Lusignan) and by Couldrette (in the poetic work Roman de Mélusine). For some scholars, these hybrid womans are derived from the Mother Goddess figure, and by their physical duality manifest their double nature of benevolence-malevolence, aggressor-donator.

If we come back to the incantation of Efimenko, we notice that the 77 daughters of Baba Yaga each have a “metly”, a “broom”. This object isn’t just the broom Baba Yaga uses alongside her mortar and pestle to travel around - it is also the main attribute of the witches, and the witch with her broom is a motif prevalent in numerous textes of Western Europe between the 15th and 16th centuries. Already in medieval literature examples of this topic could be found: in the French works “Perceforest” and “Champion des dames”, the old witches are described flyng on staffs or brooms, turning into birds, to either eat little children or go to witches’ sabbaths. Baba Yaga travels similarly: Afanassiev noted that she goes to gathering of witches while riding a mortar, with a pestle in one hand and a broom in the other. Federowsky noted that Baba Yaga was supposed to be either the “aunt” or the “mistress” of all witches. Baba Yaga herself in often called an old witch, numerous dictionaries explaining her name as meaning старуха-колдунья (staruha-koldun’ja), which literaly means old witch. Even more precisely, she is an old witch who kidnaps children in order to devour their flesh and drink their blood. We find back in other countries of Europe this myth of the “bogeywoman cannibal-witch”, especially dangerous towards newborns and mothers, as the “strix” or “strige”. According to Polivka, in his 1922 article about the supernatural in Slovakian fairytales, the ježibaba is the same being as the striga/strige. And he also ties these two beings to the bosorka, a creature found in Slovakia, in eastern Moravia, and in Wallachia, and which means originally a witch or a sorceress, but that in folklore took a role similar to the striga or ježibaba.

Vinogradova, in a study of the figure of the bosorka, described this Carpathian-Ukrainian witch as a being that attacked people in different ways. For example she stole the milk from the cows - a recurring theme of witches tales in Western Europe (mentionned by Luther in his texts as to one of the reasons witches had to be put to death), but that also corresponds to a tale of the Baba Yaga where she is depicted as sucking the milk out of the breast of a young woman (an AT 519 tale, “The Strong Woman as Bride”). In conclusion, the striga-bosorka is clearly related to the Slovakian version of Baba Yaga, the Ježibaba. The Ježibaba, a figure of Western Slavic folklore, also appears as numerous local variations. She is Jenzibaba, Jendzibaba, Endzibaba, Jazibaba, and in Poland she is either “jedza-baba” (the very wicked woman) or “jedzona, jedza-baba, jagababa” (witch). However this Slovakian witch isn’t always evil: in three fairytales, Ježibaba is a helper bringing gifts, appearing as a trio of sisters (with a clear nod to the three fatae, the three moirae or the three fairies of traditional fairytales) who help the hero escape an ogre who hunts him. They help him by gifting him with food, and then lending him their magical dogs. And in other farytale, the three sisters help a lazy girl spin threads.

In this last case, Ježibaba is tied to the action of spinning. It isn’t a surprise as Baba Yaga herself is often depicted spinning wool or owning a loom ; and several times she asks the young girls who arrive at her home to spin for her (AT 480, The Spinning-Woman by the Spring) - AND in some variations, her isba doesn’t stand on chicken legs, but rather on a spindle. This relationship between the female supernatural figure (fairy or witch) and the action of spinning is very typical of European folkore. In several Eastern Slavic traditions, the figure of Paraskeva-Piatnitsa (or Pyatnitsa-Prascovia, who is often related to Baba Yaga), is an important saint, personification of Friday and protectress of crops - and she punishes women who dare spin on the fifth day of the week. Sometimes it is a strong punishment: she will deform the fingers of the woman who dares spin the friday, which relates her to the naroua (or naroue, narova, narove) a nocturnal fairy of Isère and Savoie in France, who manifests during the Twelve Days of Christmas and enters home to punish those that work at midnight or during holidays - especially spinners and lacemakers. In a Savoie folktales she is said to beat up lacemakers until almost killing them, hits them on the fingers with her wand, beats them up with a beef’s leg or a beef’s nerves, and attacks children with both a cow’s leg in one hand and a beef’s leg in another. These bans are also found in the Greek version of Piatnitsa: Agia Paraskevi, Saint Paraskevi, who punishes the spinners that work on Thursday’s nights, during Friday, or during the feast-day of the Saint (26 of July). But her punishment is to force them to eat the flesh of a corpse. Finally, we find the link between spinning and the demonic woman/witch/fairy through the Romanian cousin of Baba Yaga - Baba Cloanta, who says that she is ugly because she spinned too much during her life. And it all ties back to the “Perceforest” tale mentionned above - in the text, the witches, described as old matrons disheveled and bearded, not only fly around on staffs and little wooden chairs, but also by riding on spindles and reels/spools.

Another typical example of “demonic woman” often compared and related to Baba Yaga is the character known as “Perchta” in her Alpine-Germanic form, Baba Pehtra in Slovenia, or Pechtrababajaga according to a Russian neologism. The name Perchta, Berchta, Percht, Bercht comes from the old high German “beraht”, of the Old German “behrt” and of the root “berhto-”, which is tied to the French “brillant” and the English “brilliant”. So Berchta, or Perchta, would mean “the brilliant one”, “the bringer of light”. Why such a positive name for a malevolent character?

In 1468, the Thesaurus pauperum, written by John XXI, compares two fairies with a cult in medieval France, “Satia” and “dame Abonde”, with another mythological woman: Perchta. The Thesaurus pauperum describes “another type of superstition and idolatry” which consists in leaving at night recipients with food and drinks, destined to ladies that are supposed to visit the house - dame Abonde or Satia, that is also known as “dame Percht” or “Perchtum”, who comes with her whole “troop”. In exchange of finding these open recipients, the ladies will thenfill them regularly, bringing with them riches and abundance. “Many believed that it is during the holy nights, between the birth of Jesus and the night of the Epiphany, that these ladies, led by Perchta, visit homes”, and thus during these nights, people leave on the table bread, chesse, milk, meat, eggs, wine and water, alongside spoons, plates, cups, knives, so that when lady Perchta and her group visit the house, they find everything prepared for them, and bless the house in return with prosperity. So the text cannot be more explict: peasants prepared meals at night for the visit of lady Perchta, it is the custom of the “mensas ornare”, to prepare the table in honor of a lady visiting houses at night. If she finds offerings - cuttlery, drinks, food, especially sugary food - she rewards the house with riches. Else, she punishes the inhabitants of the home.

But Perchta doesn’t just punish for this missing meal. Several stories also describe Perchta looking everywhere in the house she visits, checking every corner to spot any “irregularity”. The most serious of those sins is tied to spinning: the woman of the house is forced to stop her work before midnight, or to not work on a holiday - especially an important holiday of the Twelve Days, such as Christmas or the Epiphany. If the woman is spotted working ; or if Perchta doesn’t found the house cleaned up and tidied up ; or if the flax is not spinned, the goddess (Perchta) will punish the woman. This is why she was called “Spinnstubenfrau”, “the woman of the spinning room”. It is also a nickname of a German spirit known as Berchta - as Spinnstubenfrau, she takes the shape of an old witch who appears in people’s houses during the winter months. She is the guardian spirit of barns and of the spinning-room, who always check work is properly and correctly done. And her punishment was quite brutal: she split open the belly of her victim, and replaces the entrails with garbage. Thomas Hill in his article “Perchta the Belly Slitther” sees in this punishment the remnants of old chamanic-initiation rite ; which would tie to it an analysis done by Andrey Toporkov concerning the “cooking of the child” by Baba Yaga in the storyes of the type AT 327 C or F. In these tales a boy (it might be Ivashka, Zhikharko, Filyushka...) arrives at Baba Yag’s isba, and the witch asks her daughter to cook the boy. The boy makes sure he can’t be pushed in the oven by taking a wrong body posture, and convinces the girl to show him how he should enter the oven. Baba Yaga shows him to do so, enters the oven, and the boy finds the door behind her, trapping Baba Yaga in the fire. According to Toporkov, we can find behind this story an old ritual according to which a baby was placed three times in an oven to give it strength. (The article reminds that Vladimir Propp did highlight the function of Baba Yaga as an “initiation rite” in fairytales - and how Propp considered that Baba Yaga is a caricature of the leader of the rite of passage in primitive societies). And finally, in a tale of Yakutia, the Ega-Baba is described as a chaman, invoked to resurrect a killed person. The author of the article concludes that the first link between Yaga and Perchta is that they are witches/goddesses that can be protectress, but have a demonic/punishment-aspect that can be balanced by a benevolent/initiation-aspect. But it doesn’t stop here.

The Twelve Days are celebrations in honor of Perchta, practiced in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Still today, “Percht” is a term used to call masked person who haunt at night the villages of High-Styria or the land of Salzbourg: they visit houses while wearing masks, clothed in tatters and holding brooms. During these celebrations, young people either dress up as beautiful girls in traditional costumes (the schöne Perchten), either as ugly old woman (die schiache Perchten). These last ones are inspired by the numerous depictions of Perchta as an old woman, or sometimes a human-animal hybrid, with revolting trait - most prominent of them being the feet of a goose. This could explain in Serbia the existence of a Baba Jaga/Baba Jega with a chicken feet, or even the chicken feet carrying the isba of Baba Yaga. This deformation also recalls a figure of the French region of Franche-Comté, Tante Arie (Aunt Arie), another supernatural woman of the Twelve Days tied to spinning. The second most prominent trait of the “old Perchta” is an iron nose - already in the 14th century, Martin of Amberg wrote about “Percht mit der eisnen nasen”, “Percht with an iron nose”. Yaga also sometimes hag an iron nose, and this is why she was associated with other figures of Carpathian or Western Ukraine folklores - such as Zalizna baba or Zaliznonosa baba, the “old woman of iron”, who lives in a palace standing on duck legs ; there is also Vasorru Baba, the iron-nosed woman of Hungaria. Or Huld - another Spinsstubenfrau, often related to Perchta, but who has more sinister connotations. Huld has an enormous nose according to Luther, and Grimm notes that sometimes she appears as a witch with one very long tooth. This last characteristic if also recurring in Eastern Europe’s mythologies: in Serbia Gvozdenzuba (Iron Teeth) is said to burn the bad spinners ; and Baba Yaga is sometimes described with one or several long teeth, often in iron. But it is another aspect of the myths of Huld, also known as Holda or Frau Holle, that led the scholar Potebnja to relate her to Perchta and Baba Yaga.

According to German folk-belief, Huld (or often Perchta) shakes her pillowcases filled with feathers, which causes the snow or the frost ; and thunder rumbles when she moves her linen spool. It is also said that the Milky Way was spinned with her spinning wheel - and thus she controls the weather. In a very similar function, the Baba Jaudocha of Western Ukraine (also called Baba Dochia, Odochia, Eudochia, Dochita, Baba Odotia, a name coming from the Greek Eudokia) is often associated with Baba Yaga, and she also creates snow by moving either her twelve pillows, or her fur coat. According to Afanassiev, the Bielorussians believed that behind the thunderclouds, you could find Baba Yaga with her broom, her mortar, her magic carpet, her flying horses or her seven-league boots. For the Slovakians, Yaga could create bad or beautiful weather. In Russia, she is sometimes called ярою, бурою, дикою , “jaroju, buroju, dikoju”, a name connected to thunderstorms. Sometimes Yaga and her daughters appear as flying snakes - and the полет змея, the “polet smeja”, the “flight of the snake” was believed to cause storms, thunder and earthquakes. In a popular folk-song, Yaga is called the witch of winter: “Sun, you saw the old Yaga, Baba Yaga, the winter witch, this ferocious woman, she escaped spring, she fled away from the just, she brought cold in a bag, she shook cold on earth, she tripped and rolled down the hill.” Finally, for Potebnia, the duality and ambiguity of Baba Yaga, who steals away and yet gives, can be related to the duality of the cloud, who fertilizes the land in summer, and brings rain in winter. Baba Yaga is a solar goddess as much as a chthonian goddess - she conjointly protects births, and yet is a psychopomp causing death.

It seems, through these examples, that Baba Yaga is a goddess - or to be precise, a spirit of nature. Sometimes she is a leshachikha, the wife of the “leshii”, the spirit of the forest, and she herself is a spirit of the woods, living alone in an isolated isba deep in the thick forests. She is thus often paralleled with Muma Padurii, the Mother of the Forest of Romanian folklore, who lives in a hut above rooster’s legs, surrounded by a fence covered in skulls, and who steals children away (in tales of the type AT 327 A, Hansel and Gretel). This aspect of Baba Yaga as a spirit of the forest, and more generally as a “genius loci” (spirit of the place) also makes her similar to another very important figure of Slavic folklore: Полудница (Poludnica), the “woman of noon”. She is an old woman with long thick hair, wearing rags, and who lives in reeds and nettles ; or she can rather be a very beautiful maiden dressed in white, who punishes those that work at noon. She especially appears in rye fields, and protects the harvest. In other tales, she rather sucks away the life-force of the fields - which would relate her to some stories where Baba Yaga runs through rye fields (either with a scarf of her head, or with her hair flowing behind her). Poludnica can also look like Baya Yaga: Roger Caillois, in his article “Spectres de midi dans la démonologie slave” (Noon wraiths in the Slavic demonology), mentionned that Poludnica was a liminal deity of fields, to which one chanted полудница во ржи, покажи рубежи, куда хошь побѣжи !, “Poludnicaa in the rye - show the limits - and go where you want.” This liminal aspects reminds of an aspect of Baba Yaga as a genius loci, tied to a specific place that she defends. It is an aspect found as Baba Yaga, Baba Gorbata, Polydnitsa and Pozhinalka: Baba Yaga is either a benevolent spirit that protects the place and the harvest ; either she is a malevolent sprit that absorbs the life-force of the harvest and destroys it. This is why she must be chased away, and thus it explains a Slovanian song that people sing during the holiday of Jurij (the feast day of Saint George), the 23rd of April, an agrarian holiday for the resurrection of nature: Zelenga Jurja (Green George), we guide, butter and eggs we ask, the Baba Yaga we banish, the Spring we spread!”. This chant was tied with a ritual sacrifice: the mannequin of an old woman had to be burned. As such, Baba Yaga and her avatars, was a spirt that had to be hunted down or banned - which is a custom found all over Europe, but especially in Slavic Europe. At the end of the harvest, several magical formulas were used to push away or cut into pieces the “old woman” ; and we can think back of Frazer’s work on the figure of the “Hag” (which in the English languages means as much an old woman as a malevolent spirit), who is herself a dual figure. In a village of Styria, the Mother of wheat, is said to be dressed in white and to be born from the last wheat bundle. She can be seen at midnight in wheat fields, that she crosses to fertilize ; but if she is angry against a farmer, she will dry up all of his wheat. But then the old woman must be sacrificed - just like in the feast of Jurij.

The author concludes that the “folkloric” aspect of Baba Yaga stays relatively unknown in the Western world and the non-russophone lands. The most detailed and complete work the author could find about it is Andreas Johns’ book “Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale”. The author of the article tried to prove that, as Johns said, the Baba Yaga is fundamentaly ambiguous - at the same time a kidnaping witch, a psychopomp, a cannibal, a protectress of birth, a guardian of places, a spirit of nature and harvests... And that she is part of an entire web and system of demon-feminine figures that create a mythology ensemble with common characteristic - very present in Eastern Europe, but still existing on the continent as a whole.

#the yaga journal#baba yaga#slavic folklore#eastern europe folklore#european folklore#perchta#fairies#fairy folklore#demonology#demons#witches

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carnaval de Navalacruz, Ávila

#carnaval#navalacruz#avila#iberic folklore#mask#folk art#european folklore#folk magic#European paganism#pagan

205 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Krampus puts stupid adults in the Silly Bag and makes family reunions less embarrassing

#if only#traditional art#uldred#sort of#krampus#racist sexist drunk uncle goes in the Silly Bag#holidays#help#i hate this time of year#dragon age#dragon age origins#folklore#european folklore

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made a uquiz where you choose between possible variations at each stage of the story of this one european fairytale (group), and then you get to read the version that aligns closest with your choices! A little bit like a choose your own adventure!

Source of all the versions I used is here if you just want to read them all.

#fairytales#uquiz#choose your own adventure#death#grim reaper#folklore#european folklore#i've never made a uquiz before#let me know if anything needs fixing!!!

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was thinking about the difference between the British "fairy" and the French "fée", and suddenly the perfect comparison struck me.

The "fairy" from British folklore is basically Guillermo del Toro's take on the fair folk, trolls, goblins and other fairies in his movies, from "Pan's Labyrinth" to "Hellboy II". You know, all those weird monsters and bizarre critters with strange laws and customs, living half-hidden from humans, and coming in all sorts of shapes and sizes and sub-species and whatnot. Almost European yokai.

But the "fée" of French legend and literature? The fées are basically Tolkien's Elves. Except they are all female (or mostly female).

Because what is a "fée"? A fée is a woman taller and more beautiful than regular human beings. She is a woman who knows very advanced crafts and sciences, and wields mysterious unexplained powers. She is a woman who lives in fabulous, strange and magical places. She is a woman with a natural knowledge or foresight of the past and the future, and who can appear and disappear without being seen. Galadriel as she appears in The Lord of the Rings is basically the best example I can use when trying to explain to someone what a "fée" in French folklore and culture actually is.

(As a reminder: the fées of France are mostly represented by the Otherwordly Ladies of the Arthurian literature - Morgane, Viviane, bunch of unnamed ladies - or by the fairy godmothers of Perrault or d'Aulnoy's fairytales, to give you an idea of how they differ from the traditional "fae" or "fair folk". All female, and more unified, and so human-like they can pass of or be taken for humans. The "fées" are cultural descendants of the nymphs and goddesses and oracles/priestesses of Greco-Roman-Germanic-Gallic mythologies. That's why they are so easily confused with witches when they turn evil, and when Christianity arose most fées were replaced by the figure of the Virgin Mary, the most famous "magical beautiful otherwordly woman" of the religion)

#fairies#fée#french folklore#french legends#european folklore#fairy#fair folk#tolkien's elves#elves#fées

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you have ever looked at the water at the bottom of a well, you may have seen little bubbles that emerge to the surface. According to these legends from the Balearic Islands, you have seen proof that Maria Enganxa is there: those bubbles were her breathing.

In Balearic legends, Maria Enganxa (a name that could be translated from Catalan as "Mary Hooks") is a character who lives inside wells, cisterns and the underground tunnels that connect them. She has a long hook or a hand shaped like a hook that she uses to kidnap children who go near wells when their parents aren't around. These children are never heard of again.

There are different stories that explain her origin. One says that she used to be a beautiful young girl, but a witch was jealous of her and cursed her to remain underwater.

In Catalonia, legends about Maria Enganxa or Maria Ganxos exists in the Priorat and Segrià areas, where she is said to have been a real woman. She knew how to use medicinal herbs to cure all kinds of illnesses, but she also enjoyed making those who disliked her suffer: she would make cows' milk go sour, destroyed harvests and dry up the fruit trees. Seeing the situation, she was imprisoned but she escaped jail with her magic. Angry townspeople searched for her everywhere, until they found her in a field, in front of a well. Seeing she was about to be attacked, Maria said she would get revenge, particularly against children, and then jumped inside the well to avoid getting caught.

For generations, the figure of Maria Enganxa has been used to scare children to avoid getting too close to wells without supervision. The reason is that it was not that uncommon for children to have an accident and fall down the well. Other cultures have similar figures of someone inside wells who pulls children down, for example Maria Gancha from Minho (Portugal), the Marabbecca from Sicily, or the story of Banchō Sarayashiki from Japan.

#maria enganxa#llegendes#illes balears#mallorca#legends#boogeymen#mythology#folklore#urban legends#creepy#scary#witch#european folklore#myth#halloween#spooky season#minho#sicily#japanese mythology

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is your favorite folklore story or mythological tale relating to death/death-associated entities?

#death witch#death work#death worker#death deity#folklore#mythological#mythos#mythology#folktales#greek mythology#egyptian mythology#norse mythology#celtic mythology#irish mythology#arthurian mythology#any and all mythology#american folklore#United States folklore#european folklore#any and all folklore#looking for somethin to read

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Melusine

Image © @tredlocity

[Melusine is a French mermaid/fairy/dragon, who’s a surprisingly big deal considering her relative obscurity in the modern era. Multiple royal families throughout Europe claimed to be her descendants, including some big hitters like the House of Luxembourg and the House of Anjou. She was a major figure in the Middle Ages and into the Early Modern Era, inspiring poetry, art and heraldry. Martin Luther and Paracelsus wrote about her. She’s even the Starbucks mascot!

Melusine is often depicted as an ordinary mermaid, but there are two major alternate takes out there. Sometimes she’s depicted with the lower half of a dragon, not a fish, with wings and claws. Sometimes she has two tails, like the Starbucks logo. I wanted my melusine to combine these two designs, but could find nothing to my liking that had both of them. So I commissioned some art, and I think that @tredlocity did an excellent job.]

Melusine

CR 14 LN Dragon

This humanoid woman has green, scaly skin and draconic wings. From the waist down, she has two finned tails instead of legs. She wears a crown on her head.

Melusines are powerful draconic sorcerers of mermaid-like character, and they are so rare that many people think of them as a unique creature. Melusines live their lives in long alternating arcs, sometimes hiding from the world in a distant glen or ocean, and sometimes disguising themselves as humanoids in order to live among them. They desire to raise families and experience love, but have to abandon these families before their monstrous nature is found out. Most melusines make their partners swear oaths to allow them some alone time in their natural form (a weekly bath is common), and a melusine will leave if this oath is violated. Even so, melusines often watch over their humanoid children and their descendents and will intervene in their behalf if they are sorely pressed.

Melusines prefer to fight with magic rather than with claws or weapons, and few of them hide their magical powers even in humanoid guise. No two melusines have the same array of spells, but all of them radiate protective auras to support their allies and can scream to create both a powerful wave of sonic energy and deep grief in whoever survives. Most melusines carry a weapon appropriate for a mage or noblewoman, such as a dagger or crossbow, but if they are forced into melee, they can transform into the full majesty of a dragon. Some melusines are talented enough liars that they can still maintain the secret of their monstrous nature even after that transformation, begging it off as another spell effect.

All melusines are female in their natural form, but occasionally take male or another gender’s guise while shapeshifting. They are cross-fertile with all humanoids and with dragons. A melusine’s child with a humanoid will be the species of the humanoid parent, although they may have some faintly draconic characteristic (such as oddly colored eyes or hair, or even scaly patches). Many of these children grow up to become sorcerers, with a variety of bloodlines reflecting the melusine’s hybrid nature and magical gifts. One hypothesis for the origin of spellscales is that they are the child of a draconic sorcerer and a melusine, and some spellscales boast that a melusine is one of their ancestors. The child of a melusine and a true dragon will be another melusine—this occasionally happens by accident, as a melusine and a shapeshifted dragon court each other while both keeping their identities secret.

Melusine CR 14

XP 38,400

LN Medium dragon (aquatic, shapechanger)

Init +9; Senses blindsense 30 ft., darkvision 60 ft., low-light vision, Perception +19

Aura warding (30 ft.)

Defense

AC 26, touch 17, flat-footed 21 (+5 Dex, +2 luck, +9 natural)

hp 195 (17d12+85)

Fort +17, Ref +17, Will +15

DR 10/cold iron and magic; Immune paralysis, sleep; SR 25

Offense

Speed 15 ft., swim 40 ft., fly 40 ft. (average)

Melee +1 dagger +19/+14/+9/+4 (1d4+2/19-20), claw +16 (1d4), 2 wings +16 (1d6) or 2 claws +18 (1d4+1), 2 wings +16 (1d6)

Special Attacks wail

Spells CL 13th, concentration +19 (+23 casting defensively)

6th (5/day)—disintegrate (DC 23), heal (DC 22)

5th (7/day)—baleful polymorph (DC 22), dream, greater command (DC 22)

4th (7/day)—charm monster (DC 21), fire shield, freedom of movement, stone shape

3rd (7/day)—cure serious wounds, heroism, slow (DC 20), suggestion (DC 20)

2nd (8/day)—bull’s strength, mirror image, see invisibility, shield other, spiritual weapon

1st (8/day)—divine favor, expeditious retreat, mage armor, magic missile, shield of faith

0th—arcane mark, detect magic, detect poison, light, mending, prestidigitation, purify food and drink, read magic, stabilize

Statistics

Str 13, Dex 21, Con 21, Int 18, Wis 16, Cha 22

Base Atk +17; CMB +18; CMD 33 (cannot be tripped)

Feats Combat Casting, Craft Wondrous Item, Extend Spell, Flyby Attack, Improved Initiative, Multiattack, Persuasive, Spell Focus (enchantment, transmutation)

Skills Appraise +20, Bluff +22, Disguise +20, Diplomacy +26, Fly +21, Intimidate +26, Knowledge (arcana, nobility) +20, Perception +19, Perform (sing) +19, Sense Motive +19, Spellcraft +20, Swim +25

Languages Aquan, Celestial, Common, Draconic, Elven, Sylvan

SQ amphibious, change shape (humanoid or dragon, alter self or form of the dragon II), song of building

Ecology

Environment temperate land or aquatic

Organization solitary

Treasure double standard (+1 dagger, crown worth 1000 gp, 2 platinum rings worth 50 gp each, other treasure)

Special Abilities

Song of Building (Su) A melusine can sing in a fashion that duplicates either of the abilities of a lyre of building. Like the magic item, she can use the protective ability once per day, and the construction ability once per week. She uses a Perform (sing) check instead of Perform (strings) check to determine the duration of the construction.

Spells A melusine casts spells as a 13th level sorcerer, and can cast cleric spells as if they were on the sorcerer/wizard list. A melusine does not gain other benefits of the sorcerer class, such as a bloodline or bonus feats, unless she takes levels of sorcerer.

Wail (Su) As a standard action, a melusine can give a terrible wail. All creatures in a 40 foot cone take 14d6 points of sonic damage (Fort DC 24 half) and are overcome with grief unless they succeed a DC 24 Will save. Creatures so aggrieved take a -2 penalty on all attack rolls, saving throws, skill and ability checks for 1 minute, and suffer a 20% miss chance to all of their attacks, as their eyes are filled with tears. Creatures that don’t need to see are immune to the second part of this effect. A melusine can use this ability three times per day, and must wait 1d4 rounds between uses. The save DC is Charisma based.

Warding Aura (Su) A melusine radiates an aura of good luck, granting herself and all allies within 30 feet a +2 luck bonus on AC and saving throws. A melusine must be wearing a crown worth at least 1,000 gp in order to use this ability.

#melusine#mermaid#dragon#pathfinder 1e#world tour#french folklore#english folklore#european folklore#european history

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

The spirits of water with their beautiful voices. They became somewhat popular among writers as the subjects of stories.

#BriefBestiary#bestiary#digital art#fantasy#folklore#legend#myth#mythology#elemental#undine#ondine#water elemental#paracelsus#alchemy#european folklore#nereid#limnad#naiad#potamid

34 notes

·

View notes