#edge of doom (1950)

Photo

Dana Andrews & Farley Granger

EDGE OF DOOM (1950) dir. Mark Robson

#edge of doom#edge of doom 1950#classicfilmblr#classicfilmcentral#classicfilmedit#oldhollywoodedit#ritahayworrth#usersugar#ceremonial#useraurore#userconstance#userbbelcher#userdeforest#chewieblog#dailyflicks#userangela#tusershay#tuserdana#userffahey#filmedit#usermandie#uservalentina#useralex#dana andrews#farley granger#i just think they're neat#their chemistry was amazing!!!!!#dana andrews played the priest perfectly it's all in the way he touches other people#mywork

521 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan Evans as Rita Conroy

Edge of Doom (1950) dir. Mark Robson

#Edge of Doom#Joan Evans#Dana Andrews#Mark Robson#1950s#film#ours#by michi#filmedit#manderley#userteri#usersugar#userlenie#userlenny#uservienna#usercande#userelissa

543 notes

·

View notes

Text

A roasted chestnut seller on Broadway, 1950.

Photo: Esther Bubley via Esther Bubley Archive

#vintage New York#1950s#Esther Bubley#Times Square#Broadway#street vendor#roasted chestnuts#neon lights#Edge of Doom#1950s fashion#night on the town

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every Film I Watch In 2023:

278. Edge Of Doom (1950)

#edge of doom#edge of doom (1950)#2023filmgifs#my gifs#that was sooo much more nuanced and rageful than i expected#genuinely startled to hear such anti-church things expressed#in a Hays Code era film#but of course it was bookended by a lot of proper religiosity#and the voiceover was there to remind us#but i really loved how brutal and unsentimental the dialogue was#and how good all the performances were#i only wanted to hit Farley Granger a few times#he irritates me so much#but he was actually quite excellent here#and totally broke my heart when he said 'it seemed like no one cared'#of course i was there for Dana in a priest collar#and it was so fascinating to compare his performance#with Montgomery Clift in I Confess#in such similar stories#very different affect#Dana looks at everyone like he might consider snogging them#but the subtext with Farley Granger#definitely brought a strong queer energy to this#of course that might be my slash goggles lolz#also really loved the cinematography#i just love black and white film so much

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Farley Granger in a promotional photo for Edge of Doom (1950)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

It was just that...nobody cared. It made no difference to anybody what was happening to us. It was like nobody knew we ever lived. It's been that way always.

Farley Granger in EDGE OF DOOM (1950)

592 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Farley Granger for Edge of Doom, 1950

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mala Powers-Farley Granger "Nube de sangre" (Edge of doom) 1950, de Mark Robson.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Catechism for billy woods’ Church

Everyone here takes a great interest in church matters.

—Donald Barthelme, “A City of Churches” (1973)

The poison is bad for ya, stupid.

You're equal measure to dirt, dust, grime, and puss,

you're just a rapping infection...

You're pure roach.

—Kool Keith, freestyle, In Control with Marley Marl on WBLS, 107.5 (1989)

[S]he went out to look at the sky. There were no clouds at all. It was a low dome of sonorous blue, with an undertone of sultry sulphur color, because of the smoke that dimmed the air…. She looked away over the trees, which were dingy and brownish, over the acres of shining wavy grass to the hills. They were hazy and indistinct…. Sometimes a tiny fragment of charred grass fell on her skin, and left a greasy black smudge.

—Doris Lessing, The Grass is Singing (1950)

Along its eastern edge the sky’s aflame. He skulks back to his mud, his ferns and stones…is it unease he feels, without a name, or merely autumn gnawing at his bones?

—Alan Moore, Issue 27 of The Saga of the Swamp Thing, “By Demons Driven!” (1984)

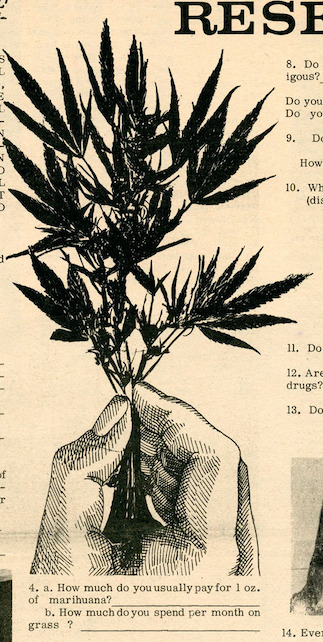

1. SYMPTOMS ARE PROLONGED AND PAINFUL

Something malodorous emitting from the Oval Office: Nixon and Reagan jacked up on the thought of paraquat. Whitey hit Mexican marijuana fields and then doubled back, raining herbicidal death on the crops that would be harvested and shipped north in the ’70s and ’80s. Stoners who thought they were stone free were instead coughing up a lung and asking where it’s from (the DEA, son—ain’t nothing nice). “Are you experienced?” became Are you experiencing side effects? “Paraquat” is about knowns and unknowns, about the acquisition of knowledge. woods deduces that the “spot on 116 must’ve had the cops in they pocket” when he peeps them selling “hydro jars [for] fifteen a pop” with a “line out the door.”[1] Not to knock that, but he’s got his own hustle thanks to a relationship hookup: “Stacy said her sister’s boyfriend had the new hot shit, / Gave me the plug like a stock tip.” He acquires the inside scoop, the insider trade, at the risk of the SEC on his back. The windfall made him a believer, he “found religion.” I’m a prophet, he declares (and its homophonics predict a propitious future: I’mma profit). Business is booming—blowing up like the World Trade. woods is feeling haughty now [from haut, “high”], “looking at the city like jihadis in the cockpit.” The knowledge got him knowsdiving. We all love to see the white man shook, so he Mohamed Atta mean-mugs with the force of T La Rock, Nas, and the Wu at his back. It’s yours, the gods seem to tell him. “It’s mine, it’s mine, it’s mine,” woods mos definitely repeats as mantra. Stares down that skyline like a metal-faced terrorist eager to claim responsibility. His impact will blow trees back and crack statues.

2.

As woods is T.O.N.Y., it only makes sense “in D.C. they called [him] New York.” Trafficking across the Verrazano so frequently that the metonym stuck despite his place of origin. Start in on that Malachi Z, though, and woods won’t suffer it; he “can’t respect it.” He’s dismissive of false idols and can’t commit to blind faith. Even if Zev Love X abides, woods echoes Brian Ennals on “Death of a Constable” who proudly affirms “and I do eat swine.” woods protests with a plate of chicharrones for breakfast while these Nuwaubians puff on Newports. Dr. York recites the Hypocritic Oath in a supermax cell. The cult leader’s not “deep in the Tombs on a humble.” No Papillon exit-plan for him. No squinting at the sun like woods says on “Headband.” On “Cellz” off BORN LIKE THIS, we learned “DOOM [was] from the realm of El Kuluwm, smelly gel fume.” Emphasis on that emanating smell—a brutal stench. woods gives it the Gas Face and the stink eye all at once—travels N.Y. to D.C. but gives a wide berth to G.A. (maybe a detour through Stankonia, though). billy woods don’t rock the white robes or take the road to Tama-Re. Oh, that shit, Dambudzo Marchera writes in The House of Hunger. There’s a lunatic fringe to every way of life.

3. THE ROACH IS NEVER DEAD

We was raised on it, right? Might should’ve said we were razed on it, by it—that’s an actual fact. Demoed the bodily temples. The Pentecostal church crumble. Oh, oh, the leaf and the damage done. Amerikkka the hell razah. What other choice did they have? They “scraped and fought,” and sometimes the “quick lick turn to a kidnap”; sometimes they wait until you’re in the car to tell you that it’s stolen. There but for the grace of God, it seemed “everybody else got caught.” Keep poison control on speed-dial for when the War on Drugs goes nuclear, for when “whitey hit Hiroshima.” Acid rain is a “light drizzle on the tarmac.” Everything soot-covered as the “black rain baptize[s].” Beaked plague doctors roam the village. The cannabis plants become bubonic chronic. On “All Jokes Aside,” woods raps that “the place smelled like Raid,” like you’re huffing the can until convulsions. What aren’t we inhaling? What are these in[hell]ants? I CAN’T BREATHE chants on carbon-coated streets beneath smoggy skies. For another bad touch example, take El-P, who warned of “sucking on lead paint popsicles.” Or Phan Thi Kim Phuc running scared, naked with napalm burns in Vietnam. Or the 55-gallon drums of chemical waste floating down the Love Canal. Fucks with your head. “The acids of gut-rot had eaten into the base metal of my brains,” Marechera writes. That’s the psychological pollution Cage spoke of on “Agent Orange,” so you better get stuck with a Thorazine solution. Rifle through the drawer for the roach clip because the roach is never dead. Raid can be damned. We’ve heard the expression before—on “Manteca,” on “ECOMOG.” A post-apocalypse eclogue: the roaches still scurrying after the fallout. Viktor Vaughn’s “Never Dead” left spinning on the turntable. The subject keeps smoking; the landscape still smoking. Apropos that it was Subroc’s sobriquet. The roach, you see, is reincarnation.

Always in anticipation of the worst, staring to the “black skies […] waiting on the thunderclap.” In the tenement, staring at the ceiling, waiting for the other shoe to drop. Guess how much black mold your tenement hold. The inevitability of it all. Hard to turn the page; harder still to start the “second chapter.” Waiting on that sky-suck: “it’s the Rapture, / Anno Domini—it’s no before, only after.” After death, though—a second life. Establish a year zero. In The Progress of This Storm, Andreas Malm sees it differently: “[T]here is nothing but the present. Past and future alike have dissolved into a perpetual now, leaving us imprisoned in a moment without links backwards or forwards.”

woods chronicled the losses on Terror Management. “dead birds” consolidated the ecological L’s into a verse:

Bread cast on water come back poisoned.

Film line the pot you boil water in.

Spoiled meat dipped in bleach.

Old oil drums the snake coiled in.

Once the goyim go in—it's microwave with the foil in.

Particulate matter stain the skin

right where it meet the respirator mask rim.

The original sin.

Nowadays he start every book at the end.

Time is running out, and it’s been in effect. Go get a late pass. We’ve been living the Anthropocene obscene, and it’s only worsening.

4.

In Fresh Kill, Shu Lea Cheang’s ecosatire film from 1994, obnoxious bons vivants dine on lipsticked fish with glowing fluorescent green pollutants contained within at a restaurant called Naga Saki. Whitey hit Hiroshima and doubled back for this queasy spoon.[2] What was fresh for ’88 wasn’t necessarily fresh at all. Certainly not fresh for ’98, or 2008, you scum-suckers. Naga Saki was serving a crudité of fresh fruit for rotting vegetables. “Isn’t that something? Seventeen thousand tons a day,” Mimi Mayakovsky says from the deck of the Staten Island Ferry as she watches a garbage barge crawl along the Hudson, headed for the Fresh Kill landfill. She doesn’t know the half. Later, a newscaster reports from a tilted TV screen sitting atop an old stove: “...investigated the possible radioactive leak of an American hydrogen bomb that disappeared off the coast of Okinawa 24 years ago…” Cut to footage of the blossoming mushroom cloud over the sea. “The Pentagon confirms that the bomb has dissolved harmlessly on the ocean floor…”

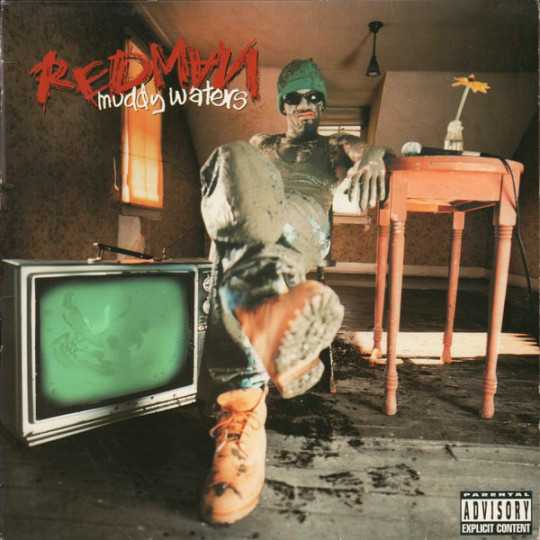

The radioactive waste insidiously infects the supply chain—it starts showing up everywhere. Shareen and Claire’s daughter plays with her toys, and a green fluorescent orb suddenly glows in her palm. They bring her to the doctor—he’s incredulous: Green hands? Green head? Turning green? Give her plenty of liquids. “‘Kill’ is Dutch for stream,” Mimi says on her public access program as the steady stream of waste becomes more apparent. The fish glow; the cats glow. Comparably, the same green as the TV screen on Redman’s Muddy Waters album cover. Jiannbin, a hacktivist when he’s not slicing sushi at Naga Saki, sits with a seemingly endless perforated ream of dot matrix copy paper. He reads from a “Globex” corporate report he’s gained access to through his late-night hacking efforts: “High levels of Technetium-99 and Iodine-129 found in fish: extremely radioactive materials.”

On the Church album cover, a brick structure towers over us courtesy of Alexander Richter’s low-angle photograph. Oxidized truss structures criss-cross at its foundation. Fire escapes are distant, rising to a vanishing point. The balcony seats are empty—nobody’s out. They shelter in place while barely visible skinny limbs of winter trees strain up from the foreground, aching for attention. These are buildings in Washington Heights, “the home of church,” Richter tells me. This massive geometric construction blots out the sun. And if you look carefully, you’ll see several fluorescent green lens flares within the intersections of the trusses—indicating that even in this brick-and-steel church, orbs of the sickness are beginning to appear.

5.

Sure, cataclysmic acts of gods and men for days. But those macro fractures don’t nag like the micro ones. You’ve got to control what you can—maintaining the mint condition of your sneakers, for instance. That’s where “Artichoke” starts: “I used to use a toothbrush to keep my kicks white—it mattered that much.” Buggin’ Out knows the struggle. You might’ve paid a hundred bucks (American dollars!), so you’re not just gonna let some sweaty white man in a Celtics shirt bump you off the block. Larry Bird befouling the pristine whiteness of your sneakers?[3] Man, you might as well throw them shits out. Them shits is broke. The situation might even turn violent. You might give that man a hundred headaches. Phife Dawg sure as hell would. “I sport New Balance sneakers to avoid a narrow path,” he raps on “Buggin’ Out.” “Mess around with this, you catch a size eight up your ass.” On “Whayback,” Tame One spoke similar of a bellicose past: “Back when steppin’ on kicks in ’86 got your ass kicked.” woods acknowledges there’s “certain things you can only learn from a fistfight.” Marechera recalls a knuckledusted fist hurtling itself at [his] teeth. Any spat could turn torrential. Marechera knows “you raise your fist at somebody and at once you are a potential killer—there is nothing manly in that. This business about ‘being a real man’ is what is driving all of us crazy.” Brothers on some ill shit, kill shit, Brewin says. Is Buggin’ Out that man? Nah, he’s just the struggling Black man trying to keep his dick hard in a cruel and harsh world.

Not a melee does every petty argument make. Just because Mookie and Vito argue over who the best pitcher in the game is (Dwight Gooden or Roger Clemens?), doesn’t mean you’ll be run out of town in a pair of Jordans. Or, worse, strangled to death for them as Michael Eugene Thomas was in 1989 (just three months before Do the Right Thing premiered in theaters). Not every quarrel over stats and standings is as heavy as Rodman sitting with the gun in his lap in the Palace parking lot. Or Spencer Haywood ordering the hit on Paul Westhead. Though sometimes relationship woes do justify the sportaphors (I mean, the blunts was like Shaq’s fingers!). Even if you loved that girl, you knew it “wouldn’t work like Harden on the Rockets.” Other times, you might be “feeling like Harden on the Thunder”—unappreciated, unloved, destined to go out like Iverson, “chucking brick after brick.” Harden ended up in Philly; “she loves me not is where [woods] landed.” (He might want to make like ELUCID on Valley of Grace and take his talents to South Africa.)

Step into a world that is bigger than you. Instead of a War on Poverty, they got a War on Drugs—and a War on Terror—so the police can bother you. You’ve gotta “move like the Black codes,” like the meadow is patterned and plotted with landmines and bear traps. “Every move [is] measured.” Avoid getting jumped by Jim Crow. Keep a “folded paper in [your] coat”—paper proving you’re gainfully employed, not some corner boy. Evade those vagrancy laws. Don’t you know bad boys move in silence and violence? “Keep [your] own counsel,” but the only Green Book you know is High Times, so you hug those papers tight to the chest; better yet—sew them into your Army jacket lining.

Pay mind to the Armageddon rap. Extinction Level Events unfolding. In about four seconds the teacher will begin to speak, but KRS is absent and woods is getting paid per diem to sub. “Open your book to Revelations,” he instructs. Learn about the “white phosphorus burning through the night”—a lesson learned before, on “Snake Oil,” which was meant to help you “see the light, white phosphorus bright.” But such incendiary enlightenment has the whiff of toxicity. The bad news pollutes your mind and you wake up to “a world made of plastic,” BPAs present in every household item (fake plastic trees, even—laced with roach repellent). Flipping pages fanatically, learning of a second death, a bubbling lake of fire, and how Death giddies up on his pale horse. “Hell followed with him” (Revelations 6:8, KJV), of course. woods watches from the fire escape: “Hellfire out the sky.” Trade out your reading material for some lighter fare, but motherfuck Billboard and the editor—’cause here comes the Predator drone. Don’t fear the MQ-9 Reaper. That “drone fly like metal kite,” which is appropriate if we check in with Clint Smith, who writes that the drone “looks as if it might be a toy.”

6. THE LOUD GROWS LOUDER

woods feels like ELUCID’s apprentice. ELUCID—the sorcerer, the spelller wordsmith and dispelller of myth, wearer of fuchsia and green, seer who unilaterally decided Shit Don’t Rhyme No More—passes an amulet of van van oil to woods so he, too, can practice many practices, get flexi with the Old Magic. Follow that Bessie Hall protocol. woods’ is familiar. Self-confessed: his great-grandmother “was a witch”—neighbors “came for poultice when they was sick. / They came when the baby was late or too early to save, but the mother lived.” Like Lauryn, she’ll hex you with some witch’s brew if you’re doo-doo. woods is no witch doctor—just a Funk Doctor. On “Haarlem,” he dressed in sauvage drag and bragged of being the “King of all Blacks” who “eat[s] human hearts.” On “Fever Grass,” he’s taking a headcount of those that are left: survivors who “ain’t got no heart.” Some mark-ass bitches.

No talisman is trick-proof, though. Cold creeps through the cracks—drafty windows and the door doesn’t seal. We’re in the “house of hunger” again—trapped, but this isn’t a trap house. Someplace wearisome and precarious, crowded and genealogical. A family affair—what’s fair? Auntie’s “bent back from the juggling” of two jobs; your mom “mumbling about [her] deadbeat husband”; your cuz trying to “get that baker’s dozen.”

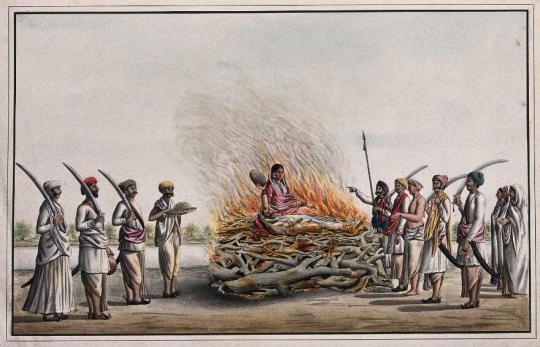

In an episode of Steel Tipped Dove’s occasional podcast A Palace from Ruin[4], woods ponders what life was like for his ancestors in colonial Jamaica. [Press play on Muddy Waters and let the intro’s nature sounds design the vision.] They lived remotely on a “mountaintop in the middle of nowhere.” woods emphasizes just how secluded they were (“deep in the bush”; “not even a town”). He describes it as a “place that sometimes feels like it stands outside of time,” which makes it even more inaccessible to him. The second verse of “Fever Grass” evokes a fever dream of what that world would look like if woods could travel back. A hale grandfather builds “God a house in the jungle”—a church!—a humble but heroic one as every brick is stacked purposefully after he “mixed cement out of pain and sweat.” Once construction was complete, “fear of the pit” had the preacher in the pulpit “hurl[ing] threats,” much like Reverend Branham’s fire and brimstone sermons sampled throughout the album. Women have it the worst, simmering in heat and sin with “bowed heads,” showing deference, sweating through “Sunday [from] sunup till sunset,” envying the “hummingbirds [that] sip from long-neck flowers” outside the church window. Their “sway” is sexy, but the churchwomen are restive, hiding the supple movement of their “hips under thin shift under church dress.”

If not from the sanctimonious, then the church seems at least a shelter from the encroaching wild—despite woods noting on “Pollo Rico” that there’s “no church in the wild.” He flows the Holy Ghost and implores the congregation to get the hell up out their seats. Preach! But the preachers in the church and the inhabitants of the house can’t withstand the insistent wilderness. Nature finds a way.

woods paints an agrarian scene, one in which villagers tirelessly try to manage the wild that surrounds them. “Sugarcane [is] stripped with machete” as men navigate the “tangled fever grass.” “Green mangoes [are] peeled with teeth,” the fruit subjugated to the famished humans. Animals are hunted, skinned, and pelts are stretched to satisfy Man’s desires—“tambourine[s] jangle” and “goatskin drums” beat a triumphant rhythm. They repose beneath the “breadfruit heavy in the trees” and admire the “stands of bamboo where roots men crop they weed.” The picture is one of Man’s victories over Nature, a modest mirrored reflection of the gardens of Versailles.

In Doris Lessing’s debut novel The Grass is Singing, Mary married Dick Turner out of desperation. They take up residence in a dilapidated house surrounded by the “miles of dull tawny veld” of Southern Rhodesia. As farmers, they perpetually fail to cultivate the land. Instead of dominating Nature, the uncooperative crops sink them deeper into debt. If only their mealie patches were as yielding as their oft-abused native laborers. Dick and Mary’s relationship strains, and Mary’s depression eventually leads to a psychotic break. As reality slips, Nature seizes upon the Turner home: “[T]he trees were pressing in round the house, watching, waiting for the night.” Mary’s paranoia and persistent fears of failure and unfulfillment lead her to personify Nature’s threat. She comes to understand “this house would be destroyed. It would be killed by the bush, which had always hated it, had always stood around it silently, waiting for the moment when it could advance and cover it, for ever, so that nothing remained.” Her mind is “filled with green, wet branches, thick wet grass, and thrusting bushes,” as she herself is invaded in the same manner as the house—they’ll be overwhelmed as one. Mary can see her own demise, though she’s apparently incapable of seeing her antagonized servants are the wilderness that surrounds her. It’s easier to imagine the end of her dwelling-place by unremitting vegetation:

...creepers would trail over the veranda and pull down the tins of plants, so that they crashed into pullulating masses of wet growth…. A branch would nudge through the broken windowpanes and, slowly, slowly, the shoulders of trees would press against the brick, until at last it leaned and crumbled and fell, a hopeless ruin.

7.

Likewise, disaster has struck on “Fever Grass”: someone or something “cut the power,” so you’ve got to learn to “thrive in the dark”—make do, [terror] manage. Time crawls and “every day is a tally mark,” but on the plus that affords you the opportunity to decide whether you’re a killer or a coward. Gotta find a way to stay “lit like wet blunts” when the blood rain starts to fall. Even as the droplets “tattoo” the “tin roof,”[5] you gotta ignite the pilot light on that “cold stove.” Play your position or get the fuck out the kitchen. For woods, the gastronome, the cold stove is a devastating setback. Havoc and Prodigy felt the temperature rising, but Marechera felt it plummet: “And I was cold; I have never been so cold in my life. The ice of it singed my very thoughts.”

Find warmth where you can. Keep lines of communication open. Those hummingbirds in the second verse network with the hum of the microwave in the first.[6] Vibrations of tail feathers communicate with the machine code in the control panel. A frequency all its own—call it Hummingbird style: 70 times in one second.

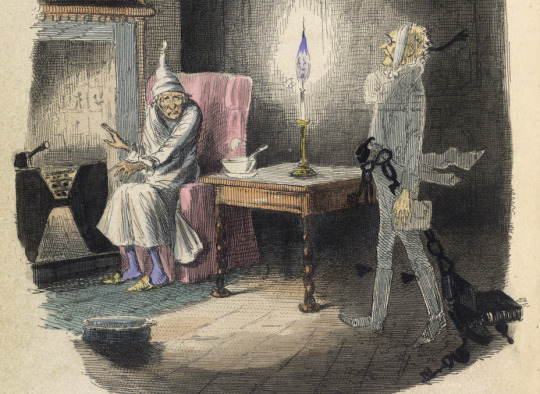

8.

The “house of hunger” that opens its rickety, rust-hinged doors on “Fever Grass”—with its “cold stove” and “madness in the cupboards” (Old Mom Dukes Hubbard knows too well that they’re bare)—clearly invokes Dambudzo Marechera. On Armand Hammer’s “Dettol,” woods hears the “rattling chains [of] Marley’s ghost” (notably, he ascribes the disturbance to “something [he] smoked”). Dickens himself calls the hullabaloo a “clanking noise.” While Scrooge recoils at the racket of Marley’s ghost, woods leans in close to listen to Marechera’s. “The chain [Marley] drew was clasped about his middle,” Dickens writes (and we figure he must “dance like [he’s] in leg-and-waist chains,” as woods says on “No Days Off”). Marley’s chain was “long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made…of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel.” Marechera’s ghost, meanwhile, drags around rich resources and raw materials for woods to seize on: Armand Hammer’s “Black Sunlight” refracts Marechera’s Black Sunlight; the gatefold of History Will Absolve Me bears an eerily relatable quote from Marechera’s Mindblast as epigraph (“My father’s mysterious death when I was eleven taught me—like nothing would ever have done—that everything, including people, is unreal”); “Cuito Cuanavale” features woods getting all autobiographical and axiomatic: “I rep my era: bridge the gap between Marechera and Sweatshirt. woods turns Slick Rick the way he wears Marechera’s chains. As Marley’s ghost haunts Ebenezer’s lumber-room, we find Marechera’s spirit haunting the margins of woods’ rhyme-pad pages. Marley and Marechera: these mar- prefixed ectoplasmic visitors don’t disfigure or despoil their hosts; they awaken them—marshaling their [literary] worlds together.[7]

9. IT’S THE MONSTERS THAT I CONJURE, IT’S THE MARIJUANA

In his songs, woods incessantly answers the questions posed by a nameless, faceless interlocutor. The question, more often than not, is: What is it? As in, “Grand Wizard, God, what is it?” (if we walk down Memory Lane). Or spasmodically like Nore on “Superthug”: What, what, what, what, what? woods answers that aphasia with anaphora—the contraction it’s predominates. On “Fever Grass,” the effect sets a scene:

It's madness in the cupboards,

It's no table manners at your cousin's,

It's humming microwave ovens,

It's auntie bent back from the juggling.

The tekneek is also suitable for meditating on problematic world affairs and your own, as he does on “red dust”:

It's not the heat, it's the dust,

It's not the money, it's the rush,

It's not the weed, that's a crutch.

It's not greed, that's not enough.

And on “Remorseless,” the effect is tonal, conveying tension and release:

It's now or never.

It's a freedom in admitting it's not gonna get better...

It's fucking over.

It's all payment pending.

It’s a mode of expression Marechera practiced as well (though he axed the contraction): “It was a prison. It was the womb. It was blood clinging closely like a swamp in the grass-matted lowlands of my life. It was a Whites Only sign on a lavatory. It was my teeth on edge—the bitter acid of it! It was the effigy swinging gently to and fro in the night of my mind.”

If it’s not this, it’s that. Black Sheep knew the score (Engine, engine, number 9…). “Inexorable—you can’t stop what’s coming.” Survivor’s remorseful Puff all up in the ad-libs with the won’t stop. A slow train coming, and you’re Perils of Pauline track-shackled. You better be coming in from the cold like Bob and the Wailers, or else Everything Remains Raw like Busta’s ill-omened The Coming. Raw lips; raw hands; raw sewage; raw meat. R-A-W: Big Daddy Kane spelled it out. “The meaning of raw is ‘Ready And Willing’ to do whatever is clever, / Take a loss—never.” No, you can’t stop what’s coming, but woods appears to say we’ve got to at least be prepared for what’s coming, which means knowing what it is.

10.

As a rapper and as a man, woods must settle with—in Marechera’s words—“this cruel externality.” The world’s harshness is ardent—burning through ozone, exposing us. Counter this overexposure with the interior world of writing. Marechera scavenged rubbish dumps for reading material. Eco-racism, check it, quite literally enabled his writing—each notebook a sacrifice zone; hypothesize this: pollution h[e]aven.

“I came up in the cesspool,” woods raps on “Fuchsia & Green.” He came UP in the cesspool; he was RAISED on paraquat—the trajectory is ascension. But he dwells in the rotten core firstly. Rite of passage with the plague rats. Marechera did it: “I was writing an article about shantytown and while inspecting the pit-latrines there I fell into the filthy hole…. It was in a way a necessary baptism.” Stagnant water special. James Joyce was christened just the same. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus is bullied by a schoolmate, Wells, who “had shouldered him into the square ditch…. It was a mean thing to do…. And how cold and slimy the water had been! And a fellow had once seen a big rat jump plop into the scum.” He falls ill as a result and spends days bedridden watching the firelight on the wall of the infirmary. These cesspools, pit-latrines, and square-ditches are transformative. Got to cope by getting positively septic. On “Artichoke,” woods “flush[es] his system with sativas.” Later, on “Classical Music,” he tells us he “flushed everything” (but the haze). Plumb crazy maneuvers to discard the waste. These sludgy skinny dips—these fully and foully freak versions of Thomas Eakins’ Swimming Hole—are swampwater sessions.

11. A TALE OF THE GREAT DISMAL SWAMP

The swamp is a gothic territory, haunted by the past. Catch a whiff of what Marechera calls the “foul breath of our history.” Stale, moldering. In “No Haid Pawn,” a piece of postbellum fiction penned by Thomas Nelson Page in 1887, the author affects a Black dialect to tell us just what the woods are: “hit’s de evil-speritest place in dis wull.” Well then. Page’s story is of a white man daring to explore the putrid pathways others have only gossiped about. He ventures into the swamp, coming upon a ramshackle haunted house once inhabited by a slavemaster who cut off the head of one of his slaves and hung it in a window. To set an example, naturally. The swamp-dwelling carries what Lessing might call an “air of bleak poverty.” Mary Turner would strive to clean it up, polishing every surface “as if she were scrubbing skin off a black face.”

Messiah Musik’s beat for “Swampwater” is disorienting. He, too, braves the overgrowth. We can hear the same ringing harmonics as RZA’s “Ice Cream” production—a residue of Earl Klugh, only warped and morphed by humic and fulvic acids. But Messiah doesn’t help us get “all up in [the] guts” of women with these swamp blues rhythms, not unless we’re talking about intestinal parasites. French vanilla, butter pecan, chocolate deluxe? Negative on that. But Messiah makes your nodding neck stiffen from the listeria outbreak on your waffle cone. Watch for the sudden spillage to the sidewalk and all the kids cry.

12.

In the swamp neck-deep…

—“The Foreigner,” from History Will Absolve Me

In 1992, Showbiz & A.G. released Runaway Slave. “I’m aware of all evil and devilishment,” A.G. raps on the title track, “because I’m living in a rat-like wilderness.” Often, the swamp is an escape route. In keeping with their ongoing argument that most slaves were content on the plantation, proslavery novelists portrayed swamp runaways as aberrations. This was a gross miscalculation. Some are still running. Your ass was running too, fast as you could, punching yourself in the chest. On “Schism,” woods finds himself “waist deep in the swamp when [he] heard the hounds.” He felt the pressure, the pangs of fear, he “felt it in [his] bowels.” It’s the feeling itself, not the hounds, that’s so much trouble to escape.

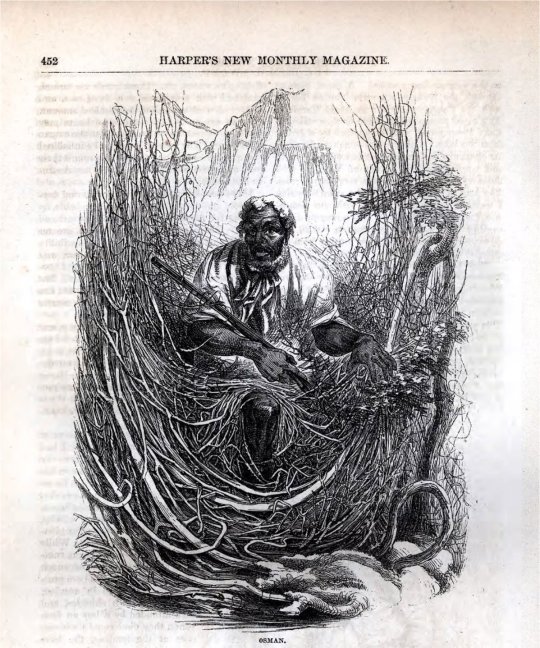

In an 1856 issue of Harper’s, David Hunter Strother published a purported travelogue of the Dismal Swamp. He’s drawn there by a novel desire:

I had long nurtured a wish to see one of those sable outlaws who dwell in the fastnesses of the Swamp; who, from impatience of servitude, or to escape the consequences of crime, have fled from society, and taken up their abode among the wild beasts of the wilderness.

Strother happens upon the cautious and watchful “Osman,” one such “sable outlaw” with a weapon in hand, fringed with reeds and willows. Strother’s account is bullshit, a fiction, but remains full of possibility. When Moses the houseboy is discovered after exacting revenge on Mary Turner in The Grass is Singing, he’s described as “a great powerful man, black as polished linoleum, and dressed in a singlet and shorts, which were damp and muddy.”

In the 1880 novel The Grandissimes, George Washington Cable seized on that same prospect. Cable broached the topic of racial injustice in his work, magnifying that which proslavery authors worked so hard to diminish: “But he was assured that to live in those swamps was not entirely impossible to man—‘if one may call a negro a man.’ Runaway slaves were not so rare in them as one [...] might wish.”

On “Swampwater,” woods fears the “penitentiary blues” he’d have to wear after one quick lick gone grievous, but he sings a penitentiary blues, too. John and Alan Lomax both recorded work-songs at prisons, including Parchman Farm, the infamous plantation-cum-prison of the Mississippi Delta. In 1940, Bukka White recorded “Parchman Farm Blues,” articulating the dream he had while inside: “I sure wanna go home, / I hope someday I will overcome.”

13.

It was blood clinging closely like a swamp in the grass-matted lowlands of my life.

—Marechera (1978)

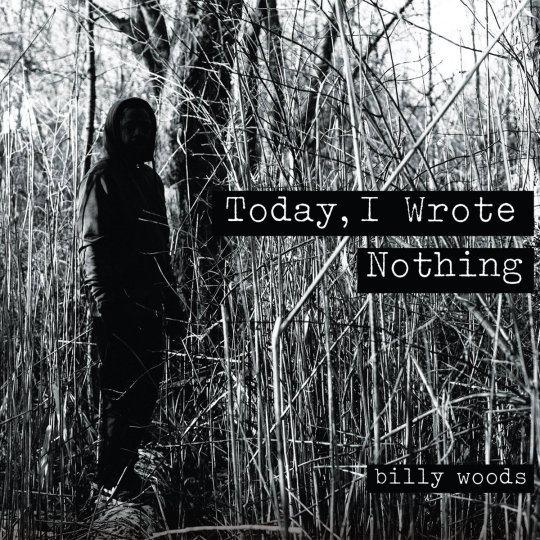

The swamp provides invisibility. Easier for Maroons to plan insurrection when caked in mud from green beanie to Timbs like Redman on the Muddy Waters cover. woods reaches for the ghillie suit, not the shiny suit. Needs something covered in sage-colored twigs and twine. He rather lurk than floss. Camouflage comes from the French camouflet (“to puff smoke in someone’s face”).[8] Smoke and mirrors stunts. On “Fever Grass,” woods speaks of the “bamboo where roots men crop they weed.” woods himself disappears in a thicket of bamboo in upstate New York on the cover of 2015’s Today, I Wrote Nothing. A. Richter brings to vision the “grass high as bamboo” that woods mentions on “Dark Woods.”[9] In the “Pollo Rico” music video, Joseph Mault places woods in lush green bamboo, too. No better cover than the backwoods. Blow that smoke in the opp’s face. A blunt brand becomes a record label’s namesake but also speaks to the shadowy wilds in which woods and his cadre navigate. Dre recreated the Zig-Zag rolling papers label for The Chronic album cover—like Backwoodz, another détournement that obscures the original context.

14. THE NUKEFACE PAPERS

Adapt and empower: that’s the necessary potion. In Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp, Harriet Beecher Stowe palms the vial of acacia powder: “the near proximity of the swamp has always been a considerable check on the otherwise absolute power of the overseer.” The swamps are “regions of hopeless disorder,” Stowe writes. The description fits much of Messiah Musik’s work on the album: the impulse is to withdraw from the frenzy, but the reward is to embrace the chaos. Emerge stronger like ELUCID on “Ghoulie,” with “mud under the nails [and] smell of swamp moss and dead things.”

Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing resembles Strother’s Osman. From his run between 1983 and 1987, Moore’s The Saga of the Swamp Thing tells the origin story of how Alec Holland, a doctor, developed a “bio-restorative formula, which was intended to promote crop growth.” Holland’s experiment is sabotaged, and an explosion sends him and “his chemical soup” into the surrounding swamp—“teeming with microorganisms.” Holland is reborn as Swamp Thing. Moore asks us to “imagine that cloudy, confused intelligence, possibly with only the vaguest notion of self, trying to make sense of its new environment.”[10]

The transformation is consummated through self-acceptance. Swamp Thing’s understanding of his own existence comes together rhizomatically. Somewhere quiet…somewhere green and timeless…I drift…the cellular landscape stretching beneath me…am I at peace?...Am I…happy? Even if woods was systematically polluted and poisoned by paraquat,[11] he still “scraped and fought” and won out in the end—he enters Another Green World (Issue 23’s title). Brian Eno’s “In Dark Trees” plays on a ghettoblaster—a Promax Super Jumbo boombox, serial number: 2014.270.2.1a, to be precise—the crusty and corrosive terminals of the D, motherfucker, D! batteries still functional. You don’t want Nunn of that. Not everyone was so lucky; so many others got caught.

Nukeface—a laid-off mineworker, a deranged drifter—became a nuclear waste addict. Perfect storms are rarely predicted, and so no one would’ve guessed the Lombard Mine explosion of ’68 would lead to a lease of land, to overflow pits being used for radioactive dumping. The man who would be christened “Nukeface” by the local street kids guzzled that waste out of beer cans with an insatiable thirst, stooping pit-side to fill a sixpack. He slurped the slag. Nukeface was the whitey who doubled back. He didn’t die—he mutated into a brain-damaged and demented tramp—and grew frustrated and embittered when the coal company sealed the mine. His supply dwindling, he fled into the damp green cosmos, crossing paths with Swamp Thing. Nukeface’s poison touch irradiated, and he seared toxic handprints into Swamp Thing’s acrid chest—a stop-and-frisk like when Giuliani was mayor, like when Bloomberg was mayor. Swamp Thing bowed his head and prayed, Let there be grass.

“How sickly seem all growing things,” Georg Trakl writes in his poem “Heiterer Frühling,” but seems is not absolute. On “Artichoke,” woods (whose name itself is so few pencil markings short of weeds) ambiguously repeats, The weeds overgrown, the weeds overgrown. Weeds are an invasive species to some, medicine to others. Weed is the town where Lennie nearly got himself lynched—the best laid plans of mice and men end up in an irrigation ditch, caught in a ravel of morning glory, waiting out the mob.

But Swamp Thing is a “moss-encrusted echo of a man,” and this is meant by Moore in a good way. He’s adorned with fibers and filaments. He settles for nothing less than the piffy with the red hairs—those cornus alba sibirica stems shooting every which way. Alec Holland has become a “ghost dressed in weeds.” Marechera might describe himself less favorably (“I was, I knew, a dead tree, dry of branch and decayed in the roots”), but he shouldn’t be so deprecating. Turn up the volume on your Artifacts tape; listen to Tame One talk of “smok[ing] the blunt that’s like a tree trunk.” Say to yourself, Just like a tree planted by the water, I shall not be moved. To survive, it’s imperative to become one with the weeds—to become weed-wedded.

15. MEDITATION IVXX

What’s that shit that they be smoking? Pass it over here. Inquiring minds want to know. The weed helps you release yo delf. Even if you don’t have that mythical Methtical strain, you’ve got options. Tical was originally called The Burning Book, and the smoke Method Man exhales from his hellified flow on the album cover doesn’t cloud our judgment, but sharpens it. Somewhere woods was in a hall plush with piff, studying the image—that scroll caught in the wind with blackletter Gothic script (like a gutted and unspooling blunt leaf), trying to decode its esoteric message. On “Biscuits,” Meth was “smokin’ on a Spike Lee joint,” while woods knew a plug with the “bomb like the Spike Lee joint.”[12] Life in marvelous times, woods adlibs at the beginning of “Schism,” and a hearty laugh to follow. On the Mos Def song of that name from 2009’s The Ecstatic, we learn “their green grass is green; our green grass is brown.” woods’ grass is singing. When the words hit us, it’s like Fat Ray says, like the first time catching a contact. You streak through the dry grass of your fears, Marechera writes—in full sovereignty of your soul. Stoned is the way of the walk, but woods pursues something loftier for the blunted. In the past, he has “scoured the Heights,” but found “no piff.”[13] He’s been fickle: “That’s okay, but that’s not the haze.”[14] This ain’t something you can just Whatever, man. This is looking for the perfect leaf. Looking for weed so strong “your limbic system not a friend.”[15] Unclasp the jewel case of Super Chron Flight Brothers’ Emergency Powers CD: unfold the liner notes to view the two-page spread of bud—a verdure set to murder the “Dirtweed” of the album’s DOOM-produced single. The expectation is super chron[ic]. You want a room “thick with smoke,”[16] a chamber. You fiend to “get stupid high.”[17] Trying to chill out, like, Everything’s okay—Quinton’s on the way.

“Check the motion while I be puffin’ the potent,” Redman raps on “Case Closed.” The motion is meditative: empty the lungs, cycle the air. Enter another green world, and another one—an anodyne and analeptic. Add kef to the tip of your spliff, feel like you can relax, “like you could disappear, like [you] wasn’t surrounded by the past.”[18] Weed as an escape from the past, but woods simultaneously dredges up his past—in that way, it’s a manual of exorcism. Questions come up, but woods “ain’t even answer—[he] just let the weed burn.”[19] He’s Frederick Douglass with the dutch, finding freedom and peace.

16. TOOK THE HAZE TO CHURCH

The immortal question: If you find a bag of weed on the floor, motherfucker, what the fuck you gon’ do? Miracles happen, and that bag of weed is a miraculum—an object of wonder. Pick it up, pick it up. Hold the church to the sky (HIGHER UP, cries ELUCID, HIGHER). Elevate the practice to the sublime. woods goes full anti-Iverson: You don’t smoke how I do—I be practicing.[20] For woods, he embraces the religious ritual—as you know, he wakes up and smokes weed. This rendition of his Fajr prayer brings him closer to illumination. Marechera concurs: “He took dagga; he believed that there is a part of man which is permanently stoned and that this was beautiful.”

billy woods steals the title of “Christ of Marijuana” from John Sinclair. For him, weed is faith. Qui fume prie: smoking is praying. He paces the nave of the Gothic church of his own making; walks the aisles to the transept; peers through stained glass to make the flying buttresses through the heavenly light. Still, in his treatise On Architecture, Leon Battista Alberti writes of a church so plain that it induces contemplation. Alberti wants the windows high, so high that one could only see the sky and not be distracted by the external world. On “Falling Out the Sky,” woods buys in and “genuflected when [he] heard the weed price.”

In John Carpenter’s 1987 film Prince of Darkness, a green substance swirls within a glass tabernacle in the cellar of St. Godard’s Church (maybe this is the “ceremony in the church basement” woods mentions on “Artichoke”). The sticky icky green spills over and into the mouths of skeptical physics researchers—a Satanic slime eager to spew its evil essence. You will not be saved by your god Plutonium, the spirit behind the computer screen types. Again, the green is the same green as Richter’s lens flare.

In Cigarettes Are Sublime, Richard Klein writes: “Smoking grass is usually a communal [act]; it draws the initiates into a circle of preference, including them and excluding others.” The weed draws a crowd; woods tracks the gatherings. Standing room only, he sits “slumped in the last pew” on “Scaffolds” and notes “the pulpit [is] packed.” On “Dettol”: “Packed house, pew to vestibule.” The homily is action-packed. People get ready—ready to die.

Usually everyone in the village—from the lords and ladies down to the peasants—joined the professional stonemasons [everyone must get stoned, if you will] in doing their part to construct an edifice to the glory of God and to the representation of the Church on earth. Churches were not merely places to go on Sunday or decorations for a town; they represented a bridge between the physical and spiritual realms—from heavy stone to heaven. The monk Suger, abbot of Saint Denis, in 1144 wrote:

I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven; and that, by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world.

Suger knew of the swamps, the Planet of Slums [rest easy, Mike Davis]. So do we. We’ve normalized our sorry plots to the point we greet each other with “my slime.” Suger had ambitions to fill his church with light. He wanted for it to be one thing: s[ub]lime.

17. IT’S SIMPLE MATHEMATICS

Bucka, bucka, bucka, bucka, bucka, bucka! The artist formerly known as the Mighty Mos: “This is business—no faces, just lines and statistics.” “Swampwater” delineates the murky business of the drug deal like a part-part-whole word problem (“copped the whole package”). woods republishes an unexpurgated edition of The Art of the Deal, proving just how artless it is. The math is weird; “Mayans never counted to here.” On “Rehearse with Ornette,” woods played Itzamna and counted bars on fingers like he was doing sums. “Vindaloo” taught us if someone fuck up the count, you pocket the difference and bounce. Take that Diddy Dirty Money where it’ll take you: fecal matter and pathogens dispersing in the air when you make it rain. “Immediately switched my math,” woods raps, staying flexible on “Alternate Side Parking.” He does not need the 99 problems. Doesn’t need the 88 keys on the piano. He keeps things pragmatic as the metric system. How he put it on “Stranger in the Village”: “Everything for sale except the scale.” woods as Anubis, weighing your heart against Truth. Meanwhile, petty pushers nickel-and-dime you—bunch of luniz with five on it but treating it like a mil. The church architects know beauty has to come correct—correct application of Pythagoras’ rules of proportion, which is a system of musical harmony. Import those arcades of Corinthian columns with semicircular arches into your DAW. The stonemason used numbers to reflect the divine order. “Think I’ll roll another number for the road,” Neil Young sings hoarsely, a throat ravaged by time and the drags of doobies. On “All Jokes Aside,” woods listens to math rock and is no doubt harangued by angular melodies and time signatures that slice ligatures. King Crimson out the guillotine type tortures. To decompress, he’ll roll a fat number.

18.

Dead church.

—ELUCID, “Smile Lines”

When the math’s right, you end up with something magnificent, like Chartres. In 1973’s F for Fake, Orson Welles delivers a passional monologue on the church. He celebrates its anonymity, seeing as how it’s “without a signature.” Many hands make light work, though, and Chartres was the effort of all for one and One for All—or maybe one for none. Welles is correct: no single name is attributed to its creation. Zero: a cypher. A circle of MCs; a circle of passers and puffers. Welles rebuffs scientists who tell us our universe is one “which is disposable” by pointing to the “one anonymous glory of all things, this rich stone forest” which is Chartres.

But Orson Welles was fakin’ jax, too. In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, he blasphemed weed. “All it does is give you extremely bad breath,” he said, adding, “it’s a terribly overrated drug.” And he only told half the story of Chartres.

“Nice church you got here,” woods says on “VX,” “be a shame if something were to happen.” In June 1194, a fire devastated Chartres. The basilica was sparking like the wiring in a Black church. Burn, Chartres, Burn—I smell a riot goin’ on. An anonymous account of the event (everything associated with Chartres is nameless, faceless) describes how “certain persons” rescued Mary’s tunic (the Virgin, not Magdalene) by moving it into the lower crypt. They stayed “shut up there, not daring to go back out because of the fire now raging.” They were protected from “the rain of burning timbers falling from above.”

Out of despair, the people, clerics, and nobility of Chartres built a new church. How high? [the exalted Red and Meth sing with the angels]. Well, high enough for the planets and the stars and the moons to collapse. Inhale deeply—until those lungs collapse. The church strain places the apse in your unfortunate collapse, lifts you back up, and constructs the Most Beautifullest Thing in this World, beautiful as a rock in a cop’s face.

19. UP IN SMOKE

Smoke clouds vision and disappears memories, but woods uses smoke to reclaim them, to shape them. Watch the chimney for the signal, for that Pope smoke from the Vatican conclave—that fumata nera. Can you smell it? It’s got that pungent skunk stink of a blunt. Joyce knew the smell.

After hearing about two boys stealing altar wine from the sacristy, young Stephen Dedalus’ thoughts wander to that “strange and holy place” and the activities he’d seen carried out there. Of particular note is a “boy that held the censer [and] had swung it gently to and fro near the door with the silvery cap lifted by the middle chain to keep the coals lighting. That was called charcoal: and it had burned quietly as the fellow had swung it gently and had given off a weak sour smell.”

Stephen often imagined himself as a “silentmannered priest,” and he would mimic his priest’s movements: “he had shaken the thurible only slightly.” Nimble movements like sealing the blunt leaves with saliva. Ultimately, Stephen knows the vocation isn’t for him: “He would never swing the thurible before the tabernacle as priest. His destiny was to be elusive of social or religious orders….He was destined to learn his own wisdom apart from others or to learn the wisdom of others himself wandering among the snares of the world.” Sounds familiar.

20.

On “Magdalene,” woods “wish[es] [he] still smoked cigarettes.” Deeper into his journey, his descent, he “[buys] a pack, [and] grimace[s] at the taste.” He needed a break to keep from breaking. Richard Klein explains that the cigarette break

allows one to open a parenthesis in the time of ordinary existence, a space and a time of heightened attention that gives rise to a feeling of transcendence, evoked through the ritual of fire, smoke, cinder connecting hand, lungs, breath, and mouth. It procures a little rush of infinity that alters perspectives, however slightly, and permits, albeit briefly, an ecstatic standing outside of oneself.

[NB: Klein’s get lifted diction: heightened, rise]

“For Kant,” Klein continues, “the sublime, as distinct from the merely beautiful, affords a negative pleasure because it is accompanied, as its defining condition, by a moment of pain.” The yellowed teeth; the morning cough; the barcode lines around the mouth. Cigarettes, like pot-leaves coated in paraquat, “are poison…they are not exactly beautiful, they are exactly sublime.” They are a way to cope, if only for the duration of the act. And so woods will “get up and roll a ’wood [and] feed the cancer in [his] chest” like he describes on “Dirge,” and he’ll feel damn good about it, too.

21.

The fire long dead—this just smoke and ashes.

—“Artichoke”

What burns never returns, Don Caballero’s Damon Che might philosophize, but I’m funkdoobious. Wouldn’t U B? Okonkwo’s rap name was Roaring Flame—he was a “flaming fire,” Achebe writes. ’Kwo sounds like he’s strutting and sashaying at the ball like Venus Xtravaganza. (Lot of rappers worry about gender-bending…) And, yeah, Paris is burning. Looking into the log fire, he’s got the nerve to call his son Nwoye “degenerate and effeminate.” How could he have begotten a woman for a son? The smoldering log sighs in concert with him. “Living fire,” Okonkwo concludes, “begets cold, impotent ash.” Better up the dosage of the blue pill or get hyper off the ginseng root. But sometimes you’ve got to johnny blaze the village to pacify the spirit of the clan. The egwugwu burn Mr. Smith’s church to the dirt. Feel its warmth, something Nwoye doesn’t get from his father’s embrace.

Is that the fire in which you burn? “Forever smokin’ the mic,” J-Treds raps, and the “lyric contact got [him] open. / Naturally higher—no need to pass the Dutchie.” Ashtrays overflow on “Schism,” indicating woods has been burning the midnight oil. Burns through pages like Royal Dutch Shell does the fields of Ogoniland. Writing in his book of rhymes until the words pass the margins. Ken Saro-Wiwa—he sacrifices himself for this shit. Ashtrays overflowing and evahflowing with church embers. The ash of Chartres. The scorch stains on your saucepan. The stinking stains of history. Trotsky and Reagan battle it out in the cypher, each flipping each other’s script, damning each other to the ash heap of history while woods writes songs about Pompeii. The volcanic ash of Vesuvius reaches from Petrograd to Port Royal. woods raps with a pyroclastic flow.

Living off borrowed time, watching the doomsday clock tick faster. Midnight in a grossly imperfect world. Waiting on the end of history, leafing through Fukuyama’s miscalculations while a thousand Fukushimas penetrate thyroid glands. “That’s what it is about swamps…too damp,” Nukeface remarks. “Nothin’ burns for long.”

22.

On “Nigerian Email,” woods promised to “break up trees on your fourth-generation imitation Premier beats.” Ya playin’ yaself if you emulate. Messiah Musik isn’t dwycking around—his beats are mellifluous dissonance. “A splinter of melody piercing the ear with brittle notes,” if Marechera had a listen. The swampwater soaks in and turns the music skronk. His loud grows louder, like the jittery strings on the first half of “Schism.” Abrasive and raucous, as loud as Loud Records, as loud as Steve Rifkind riffling record contracts in triplicate, as loud as a Mystic Stylez-era Three 6 Mafia collabo with Megadeth. All of Church’s tracks sing with a crossed signal. Doris Lessing might say it’s “that insistent screaming” you here and believe to be “the noise of the sun, whirling on its hot core, the sound of the harsh brazen light, the sound of gathering heat.” Beats that make woods want to fling inkwells and lumps of sadza. Messianic as his namesake on tracks like “Frankie,” where he composes a delicate mess to clear the moneylenders from the temple. We bask in the after-clarity and quietude. He’ll take a dime-a-dozen Goodwill copy of The Messiah and suck it through the sewer grates. What he creates is what Marechera mentions: “A cloud of flies from the nearby public toilet…humming Handel’s ‘Hallelujah Chorus.’” Messiah Musik uses oblique strategies, I imagine, to achieve sounds unthought. He shows up where King Tubby met the Upsetter and nods to the noises made by the people from the grass roots. He communicates to woods through aether talk—not stems. No stress, no seeds, no sticks, for that matter either. Songs of antimatter. Guitars channeling a Wimshurst high-voltage generator.

23.

On the legs of the piano, carved in the manner of African sculpture, are mask-like figures resembling totems. The carvings are rendered with a grace and power of invention that lifts them out of the realm of craftsmanship and into the realm of art.

—August Wilson, The Piano Lesson, “The Setting” (1987)

On Terror Management’s “Dog Days,” woods teased he might “play you some Neil Young on the piano.” Messiah Musik was his companion there, too, and it wasn’t a piano but the wheezing keys of a Hammond B2 organ we heard. On “Classical Music,” the piano does play, gently, but the drums turn the beat into a nerve-shredder—the rhythm got us sweating like the Nervous Records logo. The juxtaposition evokes something Evil [Dee], something like the “crone play[ing] keys of elephant bone” on “The Big Nothing” (an even earlier Messiah Musik collaboration). The simple fact is this: woods can’t play classical—his voice is too hardcore, “like Kool G Rap music made for concert piano,” as Bigg Jus once said. woods would maybe be more comfortable doing a boogie-woogie. Music made to get bills paid. Boogie, before it got reduplicated, referred to a rent party, and you know, you know, you know, you know the rent is too damn high. (That that Bill Withers!)

woods was a poor piano student, frustrating his tutor with the “wiry gray[s]”—she’s stressed. “Always late for lessons,” he confesses without citing CPT as an excuse. He lacked passion; he failed to put in the work: “She could tell I was guessing.” [We talkin’ about practice?] These old habits die hard, become “lifelong trait[s].” He’s “still guessing today”—still. Unfamiliar with the ebonies and ivories, “could never really find [his] place.” It’s not that he didn’t feel bad about it—how couldn’t he? She laid the guilt trip on him. “Disappointment etched every line in her face” as she listened to him fumble through the score; and, when he did fuck up, she cut to the quick. “Piano hands, she used to say, What a waste.” The criticism keeps stinging; he stays laid up in the cut (like Havoc living his hell on earth: Watch these rap niggas fuck you up). Tough to tell if it’s her or woods that’s “still disappointed today.”

She tried to school him: Amadeus’s 28th instead of church. She got dramatic (“drew the heavy shades”) and demonstrated God’s grandeur (of which the world is charged, writes Gerard Manley Hopkins) through the instrument. No cathedral necessary. He was attentive, “watched her play” as “light poured the Lord’s grace” and “rich chords” filled the place. Her performance rings of religious epiphany even if he doesn’t “quite [find] his way,” or find his faith, or find Jesus. Game recognizes game. woods has certainly kept searching (three “always” and three “find/found’s” form the trinity for our proof-texts in this exegesis).

If there was spirit to be found, it was the spirit of the hustle. Boy Willie, the watermelon-selling brother in August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson, wants to pawn the family piano against his sister’s wishes. Berniece argues, “Money can’t buy what that piano cost. You can’t sell your soul for money.” But Boy Willie doesn’t fetishize the hulking heirloom: “I’m talking about trading that piece of wood for some land.” He pays no mind to the supposed magick of the piano. billy woods plays Boy Willie, you see—disillusioned, hell-bent on any inheritance he can hardscrabble together.

Doaker, the siblings’ uncle, explains that Berniece believes the piano “got blood on it”—and it does. “I don’t play that piano cause I don’t want to wake them spirits,” Berniece explains. Doaker eventually elaborates on the history of the piano, how Sutter the slaver traded a mother and child for it, severing the family over an object. The slavemaster’s wife was given the piano as an anniversary gift but missed her prized domestic slaves. Sutter forced the patriarch of that splintered family to flex his carpentry skills (“a worker of wood”) and carve their faces onto the piano. Years later, while Sutter was celebrating at a Fourth of July picnic, Boy Charles (Berneice and Boy Willie’s father) liberated that piano. Consequently, he was hunted down and burnt up in a boxcar.

At the end of the second act, Sutter’s ghost rears its honky head in an attempt of reclamation, but Boy Willie fends it off in “a life-and-death struggle fraught with perils and faultless terror.” Her brother needs help, so Berniece finally plays the piano, and what she plays is “both a commandment and a plea. With each repetition it gains in strength. It is intended as an exorcism.” The song she plays is “a rustle of wind blowing across two continents,” and it keeps Sutter’s ghost at bay. Boy Willie realizes generational wealth is its own curse. What we already know: Anything you want on this cursed earth probably better off getting it yourself.

Berniece plays the “old urge to song” and the song is “found piece by piece,” meanwhile woods “played the piece till it fell to pieces”—into micro-fragments, Saafir would say. Chasing ghosts, chasing ghosts, woods chants. (What ghosts? Sutter’s ghost? The ghost of the Yellow Dog?) woods’ “arpeggios break,” doin’ damage with the fracturing [JVC] Force of a Black Flag nervous breakdown or the “Stop Breakin’ Down Blues” of Robert Johnson. The verse itself breaks down into a mosaic of memories (from piano lessons, to religion, to culinary, to drugs). Broken down completely, woods needs to build up. He “sifted seeds”; he “made niggas believe when [he] grated cheese”; he was “proud to be accepted.” In the end, “the police rush the gates,” and the splendor of the ocean floor becomes an unseemly flushed toilet (though he “couldn’t bring [himself] to flush the haze”). The simultaneous storylines of his life follow this indirect pattern. Lessing writes: “He arrived at the truth circuitously: circuitously it would have to be explained.”

24.

On “Frankie,” the titular character is as her name implies: direct. Despite her bohemian trappings, she doesn’t tantalize woods—she vibes with him. She gives it to him straight, no chaser. We’re blessed, too—a rare linear and localized narrative. The setting is Morningside Heights, “back when the building was nice”—in other words, “Frankie” is an idyll. The halcyon days. The song isn’t on the mourning-side; rather, it helps us reach the heights of a vaulted church ceiling. The elevator may “grind and hiccup,” but, nonetheless, it allows us to get lifted. Keith Murray is our elevator operator, and we’re moving on up in the world. Me and you, your mama, and your cousin, too—woods brings us all along.

What appears platonic at the initial pass might be more amorous than anticipated. “Frankie” is a spiritual ascent. The “old biddies out front with The Watchtower ask if [woods] know[s] Christ,” but he walks with purpose past the extended arms with the JW rag. He walks determinedly, faithfully, not ashamed to bow his head and “pray [the elevator] don’t get stuck.” He moves in spirit, inspired—it’s not the breath of God which gives him life, but the expectation of a climax. “Black pussy is the world’s first religion,” ELUCID says, so when Frankie “buzzed” woods up, it was unquestionably a love buzz, a tingling sensation.

Frankie’s “whole floor smell[s] like nag champa”—a fragrance that rescues him from the rank city streets. A frankincense aroma to the strain. Frankie is neither hag nor nag. She comes correct with mysticism—eastern medicines to cure his western illnesses. A sacred space: leave the “shoes at the door.” Her “roommate was Shanta” (Shanta? Shanta from the Rāmāyana?). They’ve got “rugs like 1970’s Cairo,” but the furnishings are less emblems of Edward Said’s “exotic sensuousness” and more an exposition of exxxotica. The filth of second-hand finds. “Half the stuff in here they found on the street,” woods says. “I helped carry that TV—stupid big.” At the beginning of Fresh Kill, Shareen Lightfoot carries a TV through a homeless encampment—all tarp shelters and crap-filled shopping carts—and loads the set onto a wall of other binned boob tubes. Near the end of the film, Shareen admonishes her partner Claire as they carry a pink piece of furniture down the block: “Claire, be careful. This is a Joséphine Empress chaise lounge, okay?”

Every spot in the apartment his eyes settle on is an aphrodisiac—dope and dopamine. For weed, woods “had to burn it raw” (a prelude to the fires still to come), and the cannabis got his receptors hot and bothered. His relationship with Frankie is, without question, an intoxicating one.

She spins “Dick Gregory on vinyl”; my money’s on the 1970 Frankenstein album, pun intended. “They say more bad things about the drug users than they do about the pushers,” Gregory remarks. “They don’t say nothing about the cat in the silk suit and the alligator shoes that’s pushing that stuff.” Shanta’s role is selector. An hour later, sounds from Jamaica, or Nigeria (can I recommend Side A of Fela’s 1973 Afrodisiac?). Frankie moves to the music, skanking, before Shanta settles on Sade’s “The Sweetest Taboo.” Now woods is burning candles—and sage—and all his other plans got canceled.

They “roll Js on [an] Amharic Bible that [Frankie] found on 113th.” woods can’t let this opportunity pass him by. Why? Because Frankie is the dopest Ethiopian. Redman’s somewhere out in Jerz nodding approvingly as the couple Smoke Buddah. (Shanta has dipped by this point.) woods inhales deeply and slumps against the trunk of the Bodhi Tree. I got a slight problem: I smoke weed too much. But there’s no problem here.

Frankie gives new meaning to old flame. Her corner apartment is infused with light: “the sun run riot.” Rays of light beam through the “French doors”—you can get lost in the floating motes. The “hardwood [is] shining,” and Frankie herself is illuminated, “looking like she might just burst into fire.” Maybe woods’ love sickness is lethal and he’s dead already, and Frankie’s a ryde-or-die bitch practicing suttee. Maybe this is her spontaneous human combustion, sunstruck. No stench of accelerant, and her demise has a Calvinist bent. Perhaps punishment for her untold sins, the corruption of her spirit. Doctors once theorized an individual too intoxicated was liable to become flammable. Frankie was too lit. Shit, it happened to drunken sailor Miguel Saveda in Melville’s 1849 novel Redburn. He was relegated to a bunk in the forecastle, and when they checked on him later, he had “two threads of greenish fire, like a forked tongue, [that] darted out between the lips; and in a moment, [his] cadaverous face was crawled over by a swarm of worm-like flames…while covered all over with spires and sparkles of flame, that faintly crackled in the silence, the uncovered parts of the body burned before [the crew].”

Or maybe they burnt all those herbs and their persons to purify. The summer months burn by. woods and Frankie sit at the open windows and listen to the “broken jazz float in.” Messiah Musik liberates the plinks of piano, and his horn sample blares funereally. He’s Henry Caul in the final scene of Coppola’s The Conversation, blowing his sax in his tore-up from the floor-up apartment, exasperated, having not found the bug. For woods, Frankie’s big windows have gotten tinier—what do you expect? He followed the White Rabbit and drank from the “drink me” bottle, did he not? Frankie with the Cheshire cat grin. Her fire melts the Italian ices, those “Marinos left out till slightly unfrozen.” That’s how he wanted them anyway. Patient, just “waiting for that moment.”

25.

Nirvana turns to drama on “Cossack Wedding.” woods is a “disaster tourist wandering” Chernobyl.[21] He’s touring the ravages of a calamitous relationship, one which has left an “alienation zone…30 kilometers wide.” He wends through scabrous wildlife, and we follow his extended metaphor wherever the umbrella leads, even if we’re guided to the ruins of a reactor explosion.

woods is not a disaster tourist so much a disaster capitalist, of sorts—I mean in the way he mines the past for the profit of his spirit (and ours when we hear it expressed in song form). But dude is radioactive ill—bilious woods with the broken heart. His core melts. “Never again would I suffer wholeheartedly for any woman,” Marechera writes. How could he if his heart is dissected, atriums to the right and left? woods looks like he’s seen a ghost and is turning over Ghostface lines in his head. His heart is cold like Russia after the breakup, breakdown. “For those cold wars you need endurance,” but woods just don’t have it in him. A partnership that once warmed the cockles of his heart now cancers the conjugal visit. Contaminants stain the sheets of the connubial bed. Throw the Magnum to his head and squeeze until the bed’s completely red. He feels isotopically iced out. Feast on mercury fish (unavoidable). Hot wire his heart. Put an end to all this cold chillin’.

She dresses down to a demure “black bra strap,” but the sex is a mess. “Never nothing lurid” save for the “dead fish [and] wild boars swollen with tumors.” “Radiation flow out [his] phone jack like a Keurig,” because the best part of waking up is caesium in your cup. The love doesn’t last; the communication breaks down. Only “snippets of dialogue” detected. He might crack a smile but ain’t a damn thing funny. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder—to hold her, to swim in her “aqueous humor,” growing more splenetic by the second.

The chorus offers clarity: “I’m a sucker; I fall for it every time.” Every time—so this is a pattern of behavior. The past is not without incident. Chernobyl had partial meltdowns in ’82 and ’84 prior to the big blowup of ’86. woods is sympathetic when he self-deprecates: I’m a sucker. Sucker M.C.’s: move back, catch a heart attack.

The bubbler pools boil over, ooze corium: woods and the missus consider whether to give it another go. He reminisces on what was—the books he’d loaned her. DFW’s A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again was a miss (the title itself befitting of his synopsis on what they had between them).[22] As for the Solzhenitsyn? “She skipped to the end.” The novel in question is the 500-page Cancer Ward, no doubt. In it, Kostoglotov scans a health department certificate—“On it was written: ‘Tumor cordis; casus inoperabilis’ [cancer of the heart].” The whole library love affair sums up to say less. Yet Lessing says more of Mary Turner:

It had been a drug, a soporific, in the past, reading them; now, as she turned them over listlessly, she wondered why they had lost their flavor. Her mind wandered as she determinedly turned the pages; and she realized, after she had been reading for perhaps an hour, that she had not taken in a word…. For a few days the house was littered with books in faded dust covers.[23]

That isotope chill prevails. woods feels “the cold creeping in [his] bones.” Creeping, because he’s creeped-out. Gone from creeper to crept-upon. Feels it “in [his] bones” like a neoplasm—deep in the marrow. Bones thugged in disharmony. She’s Creepin on ah Come Up. Like a force of nature, her “wind whip around [his] home,” spookily. “She came when I’m sleeping,” he says, vulnerable as can be. A succubus looking for a sucker. Postpartum possibly, what with her “breasts leaking [and] pussy unkempt.” The description is adjectivally nauseating, in Marechera’s words.

Wasn’t only her uglies going bump in the night. Ethereal beauty emerged: “Around her the light bent.” She was aureoled—something saintly and subtle; not like the raging immolation of Frankie. Not the excessive sunlight of Frankie’s loft either—this light is ambient, “like an opium den,” with the requisite narcotic effect. An air of mystery: “[He] couldn’t quite see her face.” She was dressed in all black like The Omen [can’t spell women without it—am I right, fellas?]. Her fashion sense is dour like the weed she got “from her friend.” She moves with the night, wears its cloak. He pulls on the “piff with a fragile stem,” and we consider the fragility of his mindstate. You gots to chill, he tells himself. “I mind my business,” he raps. Strictly business. It’s a lesson hard-learned. Stay the fuck up out my biznass. “A very bad business,” the people say of Mary Turner’s death at the hands of her houseboy. “Nobody beats the Biz,” woods sings. The M-A-R-K-I-E might make the ladies scream and shout and be bound to wreck her body, but this ain’t no party, woods ain’t no king of discoing. “Real mens mind their own business,” Daniel Dumile definitively said. woods always with that palm-to-the-camera pose—behind that, he’s still Mugabe in a DOOM mask.

He needs a double portion of protection—some [will-]power beyond prophylaxis. Strives to keep the “wolves behind the fences.” This means setting “snares in the snow.” This means he’s “dug trenches,” “mined roads,” and “interrogated peasants,” but his precautions are futile: the “wolves [are] at home in bed.” We’re reminded of reliable hiding places. You’ve got to peel back the glossed lips and “peep the teeth like a dentist.” You guessed it: toothy: long and glistening. I think it’d be in your best interest to dead the Little Red Riding Hood worries and, instead, polish your Red Army Faction tactics. Might need a Heckler & Koch MP5, because her passions and ploys make her Meinhof more formidable than your Baader. There’s no keeping her down or out: “In the morning [his] pillow smell[s] of pine cones.”

26. SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN-EYED BANDIT

My betrothed fled to the forest, hid in the pines

Still set a place for her, unlatched the door so she could come inside.

The encounter in the forest carries a chivalric quality, though chivalry is dead of a malignancy. We had the lady by the throat—carcinoma hugging her thyroid—yet still she pursues her lover. woods’ “Cossack Wedding” runs parallel to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. While sheltered in a lord’s castle, the lord’s lady seeks to seduce the young knight. With the lord busy leading a hunt “through a lime-leaf border” [cue Nate Dogg: smoke weed everyday], the lady sneaks into Gawain’s room. She finds him “slumbering in his sheets, / dozing as the daylight dapple[s] the walls.” Gawain, woozy, hears “the sigh of a door swinging slowly aside.” He lapsed by not locking the door (much like woods who “unlatched” it). He lifts his head and discovers the lady “looking her loveliest…craftily closing the door.” He feigns sleep, but the lady “cast[s] up the curtain” of his bed “and crept inside” [...yeah, just keep it on the down-low]. He fake-awakes, and she tells him, You’re tricked and trapped! She proposes a truce, threatening to “bind [him] in [his] bed” if he doesn’t agree to it. Gawain, recognizing the situation, refers to himself as a “prisoner” and asks her permission to dress, stalling. She denies the request and says she’ll “tuck in [his] covers corner to corner, / then playfully parlay with the man [she] [has] pinned.” The lady isn’t “hid in the pines” like woods’ stalker; she’s got him pinned. The lady tells Gawain, “do with me what you will. / I’ll come just as you call.” woods’ refrain of “...so she could come inside” hits different in those castle walls and bloody chambers. Ahooga!

27. SHE’S DRIVING ME OUT OF MY MIND: THAT GIRL IS POISON

Angels in white ask why she’s weeping: And they say unto her, Woman, why weepest thou? She saith unto them, Because they have taken away my Lord, and I know not where they have laid him.

—John 20:13, KJV

“She said, Come get me and I’m yours,” woods testifies on “Magdalene,” but the communication has gotten so poor that the line actually “went dead.” Unlike Mary Magdalene, woods’ Magdalene won’t even approach the sepulcher. She wasn’t present for his crucifixion. She rather play the coy mistress. Come get me…. She offers herself as a possession on some Craigslist killer shit: CURB ALERT. Casual encounters have been SESTA-ed out of existence. This ain’t the glory days of “Ca$h 4 Gold” when woods could ask, Do I know you from Craigslist? Those erotic services have been Ctrl+Alt+Deleted. Not a “spray tan and glitter” situation either. On “Schism,” woods stumbles into “a strip club everywhere [he’s] touring,” but Magdalene isn’t a dancer “bent at the waist, left cheek on the mirror.” What’s sacred, what’s suitable? ELUCID queries. What’s profane, Magdalene? The wayward woman. You could imagine a time when she twerked—put her thing down, flipped it, and reversed it—as orgasmic as Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, but now she’s in distress with seven devils swelling in her silicone chest.

woods wants to keep her talking—he puts “bread on her phone” like some Eucharistic handout—but a bad penny finds its own way to hell, and Magdalene shuffles about as da baddest bitch since Trina. Brother on the phone tells woods, “She don’t wanna be saved—get it through your fucking head.” He can’t, though—he’s thick. Can’t accept he’s a savior denied, his overtures met with threats—he’s stubborner than that. woods is in hot pursuit, and his verse on “Magdalene” is a road novel.

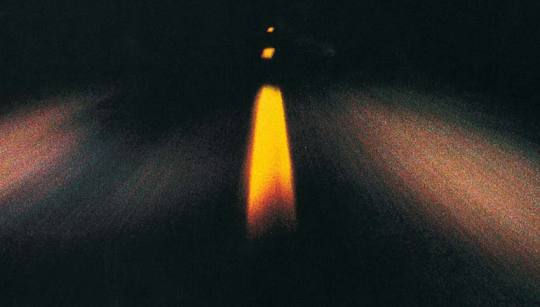

This isn’t woods’ first foray into the genre. “Magdalene” calls back to “Sleep” from Today, I Wrote Nothing, but his latest car journey is far lonelier and grim—more big sleep than sleep. He’s driving unaccompanied, approaching the interchange of the road to Parnassus and the road to perdition. McCarthy’s “cities of the plain hum in the distance,” brimstone and fire falling fast as the AM radio static of a Reverend Branham sermon intensifies. At turns, as disquieting as a joyride in Christine from Mandeville to Sligoville. On “Swampwater,” the car ride was a commute with “really no time for fear.” Only had to compete with the “dying sun glare through thin atmosphere, [the] windshield smeared, [and] AC blasting old air.” Progress was on pause: “standstill traffic.” On “Pollo Rico,” woods recollects how his “heart used to sing crossing the old Goethals.” And on “All Jokes Aside,” he’s counting the cars on the New Jersey Turnpike like Paul Simon, gone looking for Amerika.

With “Magdalene,” woods’ actions are deliberate, not whimsical. He “slept all day so [he] could drive the next.” Early to rise, it was “still dark when [he] left.” The drive is immediately desolate—not gridlock’d, but “streets empty.” He hankers not for nicotine, but for the ritual that comes with smoking a pack. He tries not to fixate on the “check engine light lit.” The day ends as quickly as it begins. woods clicks on the high-beams, and those “brights plowed the night.” He’s alone in his eternity at the wheel, as Kerouac says. Like in Lynch’s Lost Highway, the dashed yellow lines of the asphalt-black road are swallowed up by speed.

There’s nothing too sexual about woods’ check engine light—nothing on par with ELUCID’s pleading Suck my dick and tell me I’m beautiful, anyway. woods is a forsaken man, and only so much lust can be summoned from his vehicle—the good vibrations of the rumble strips along the shoulder, okay, the quivering chassis—but his whip isn’t anywhere near as erotic as Robert Johnson’s ride on “Terraplane Blues.” Like woods, Johnson “feel[s] so lonesome” on the 1936 recording, but his “moan” is libidinous. He longs for his lady, eager to “hoist [her] hood” and “check [her] oil.” Where woods ignores the check engine light, Johnson pulls out his dipstick with the quickness. He wants to charge his lover’s batteries, give her generator a spark, and tangle with her wires. He holds out hope that her “spark plug will give [him] fire.”

woods can spot the cell towers on the horizon—the signal reliable enough for a “split-lip selfie” to come through. Not the first time—and likely not the last time—Magdalene has been hit, vows of gentleness notwithstanding. The man Magdalene is shacked up with readies “his great hand swinging yet again to smash,” like Marechera writes—prepared to “beat her until she [is] just a red stain.” Words chosen more carefully when the threat of violence in the air.