#despite the complete omission of Jane in the article

Text

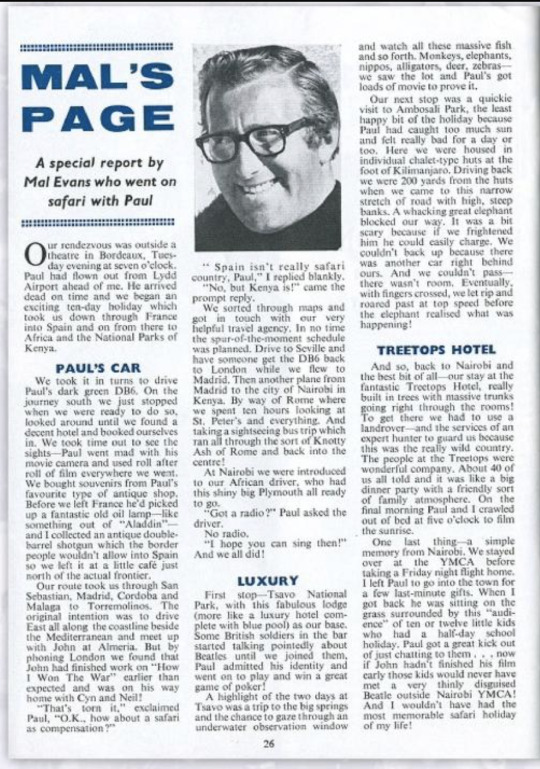

#Beatles Monthly#issue 42#January 1967#Paul McCartney#Mal Evans#Jane Asher#despite the complete omission of Jane in the article#I didn't know Paul was planning to visit John in Spain#Slightly related: The Family Way came out in December and John finished filming in November#How would the timing ever have worked out for them to write the score together?#This is also The Moustache Trip

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is the most one-sided biography of Mary Stuart, “the unluckiest ruler in British history”, for years. Even Lady Antonia Fraser handled some of the more controversial incidents in Mary’s life – the discussions over the fate of Lord Darnley at Craigmillar Castle in November 1566, or Mary’s “kidnapping” by the Earl of Bothwell at the bridge of Almond in April 1567 – with caution. Guy simply accepts Mary’s account as gospel. Lady Antonia’s Mary is essentially the story of a redeemed sinner. In 1988, Jenny Wormald mounted a challenge to the sympathetic approach, in Mary Queen of Scots: A study in failure. If little more than an extended essay, it was still based on Wormald’s own revisionist studies of the Scottish nobility, which replaced the cliché of an unruly and factionalized country with an emphasis on the constitutionalism of Scottish political behaviour. Mary was a failure not just because she was both indecisive and not very bright, but because she attempted to rule against the grain of Scottish politics.

Guy will have none of this. His Mary is a model ruler who faced a violent, self-seeking and greedy Scottish nobility (no revisionism here) and an organized clique of republican (Guy’s term) Presbyterian bigots led by John Knox and George Buchanan. The novelty of Guy’s approach lies in his attempt to write Mary’s life from the perspective of what can be called the “St Andrews school” - Roger Mason, Jane Dawson, Guy’s own student Stephen Alford, and most recently Pamela Ritchie – who for two decades have dominated the study of Anglo-Scots relations in the sixteenth century. Their central argument is that Scotland was the prey of two rival imperialisms, one French and Catholic, the other English and Protestant. Mary was herself the agency of the French scheme, serving to unite Scotland to France through her marriage to Francis II. At the same time she was the barrier to a Protestant union with England. Her strongest enemy was not Elizabeth I, but Elizabeth’s secretary Sir William Cecil, the principal supporter of a Protestant union. Having seen Mary as the main threat to his plans, Cecil (whom Guy calls Mary’s “nemesis”) assiduously sought to remove or destabilize her. Curiously, Guy’s Mary has no dynastic ambitions herself, she was simply the victim of the wider imperial rivalry, in which her French relations were as self-seeking as her Scottish enemies.

It comes as no surprise to find Guy arguing that Mary was innocent of the murder of her husband and that the famous Casket Letters were forgeries. The conspiracy behind Lord Darnley’s murder was masterminded by the future Regent, James Douglas, Earl of Morton (“the most sinister of the leading Lords”), but instigated by Cecil. There is nothing particularly new in accusing Morton, but there is in accusing Cecil. Unfortunately, on his own admission, Guy cannot prove the charge: “It is not, of course, that Cecil conspired to assassinate Darnley: he was far too clever for that. But, from the beginning, his policy towards Mary had relied on attempts to destabilize her rule by causing mayhem at critical moments”.

On the Casket Letters themselves, Guy follows Gordon Donaldson and Lady Antonia in arguing that the letters were not necessarily complete forgeries, but manipulations of otherwise innocent items. This case for forgery is made largely on textual grounds and for that reason it suffers from a certain subjectivity. At the same time the forgery claim has created a further issue, which has not (to date) been adequately addressed. If the letters and the documents associated with them are accepted as genuine, there is a coherent account of their discovery. As Buchanan observed, Bothwell saved them as an insurance policy in case Mary tried to repudiate him and make him the scapegoat for Darnley’s murder. They were brought to Morton’s attention between June 19 and 21, 1567; a considerable number of people were aware of their existence in June and July 1567; and they are mentioned in the Act of the Scottish Parliament justifying Mary’s “retention” in December 1567. Finally, copies were in circulation in England in the summer of 1568, before the originals were brought south in the autumn.

If, however, they were forged, when did the forging take place? It could only have been undertaken in concert with the drafting of a narrative of Mary’s misdeeds (which took its ultimate form in the Book of Articles) that the letters were to substantiate – a point Wormald has appreciated. Lady Antonia dated the forging to the summer of 1568, when Mary’s arrival in England made it necessarily to prepare a case against her. How then are the 1567 references to be explained? Even if Morton’s account of how the letters were found is also dismissed as a fabrication (despite the fact that he cites a number of witnesses, not all of whom were allies of his), the others remain. Guy does not tackle this issue directly, except by bringing up an apparent discrepancy between Morton’s account and the Act on Mary’s imprisonment. Morton’s account of how the letters were found during June 19-21 is contradicted by the Act (Guy states), which declared ‘“the cause and occasion of their taking the said Queen’s person upon the said 15th day of June’ was ‘by divers [of] her privy letters’ said to be wholly in her handwriting. These Lords [sic] confidently assured Parliament that Mary’s letters had been found before they had forced her to surrender…”. Unfortunately, what the act actually states is that the cause of the taking of the Queen’s person on June 15 and all the actions “touching the said Queene” since the death of Darnley “wes in the said Queenes awin default [my italics], as in sa far as be divers her privy letters… and be her ungodlie and dishonorabill proceding to ane pretendit mariage… it is maist certain sche was previe, airt and pairt… of the murther”. The letters were cited only as evidence of Mary’s “default”; it is not even implied that they had been found before June 15.

This example of selective quotation is not unique. One of the problems of “My Heart Is My Own” is Guy’s curiously casual handling of evidence. He also succumbs to the inherent fallacy of conspiracy theories. There is an “official account”, which is microscopically examined, every discrepancy noted, every omission considered suspicious. But when the conspiracy is finally unveiled, it is based on evidence even more flimsy than the official account. The conspiracy here is not Scottish, but English. At its heart was William Cecil, who masterminded Mary’s downfall from 1559 until her execution in 1587, as well as plotting the destruction of English Catholicism through a series of fabricated plots against Elizabeth – a conspiracy theory the Jesuit historian Francis Edwards has been arguing tirelessly since the 1960s. Guy quite rightly observes that the rivalry between Elizabeth and Mary has been greatly overplayed and that Elizabeth was more willing to reach a compromise with Mary than she has been given credit for. He is also justified in emphasizing that Cecil was more suspicious of Mary than Elizabeth. I pointed out, in 1987, that the distrust of Mary that Cecil and his brother-in-law Sir Nicholas Bacon shared was little different from Knox’s. But at the end of the day, Cecil was Elizabeth’s servant and it was her policies that were implemented. The one obvious exception was Mary’s execution, but the explosion that caused is conclusive proof that it was not business as usual. As his treatment of Lord Darnley’s death reveals, much of Guy’s Cecilian conspiracy is innuendo.

“My Heart Is My Own” is a tribute to the fascination that Mary Stuart continues to exert. This in itself is not surprising, for, as the Romantics fully appreciated, she was a Greek tragedy in kilts. The fascination may also explain why Mary’s historiography has been littered with conspiracy theories, the most important of which she started herself. Nevertheless, one would have expected a historian of John Guy’s calibre to have employed a little more discrimination in his treatment, not so much of Mary, but of her contemporaries, who are reduced to the level of caricatures. The result is not a radical new interpretation, but another in the long line of Marian apologias.”

Simon Adams reviewing “My Heart Is My Own”: The life of Mary Queen of Scots by John Guy. “Queens’ Moves.” TLS, no. 5267, Mar. 2004, p. 8.

#Simon Adams#John Guy#Mary Stuart#Mary Queen of Scots#William Cecil#Elizabeth I#historiography#Simon Adams is the voice of reason again

52 notes

·

View notes