#coty perfume

Text

Daily Vintage: Coty Fragrances

#vintage tips#vintage blogger#vintage lifestyle#vintage life#vintage beauty#vintage fashion#vintage#vintage style#vintage hair#vintage makeup#vintage fragrence#vintage ad#vintage christmas#coty perfume

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

US Vogue October 1, 1952 ❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

In Bianchini silk-chiffon, an indoor ensemble by Traina-Norell, with a warm mink ripple highlighting the neckline, and the timeless allure of two very pale pink roses. Bracelets, earrings and ring, by Marvella. Invisible accessory: a drift of perfume, “Emeraude” by Coty.

En mousseline de soie Bianchini, un ensemble d'intérieur par Traina-Norell, avec une ondulation chaude de vison soulignant le décolleté, et l'allure hors du temps de deux roses d'un rose très pâle. Bracelets, boucles d'oreilles et bague, par Marvella. Accessoire invisible : une dérive de parfum, « Emeraude » de Coty.

Photo: Horst P. Horst

Model/Modèle: Ruth Neumann

vogue archive

#us vogue#october 1952#fashion 50s#fall/winter#automne/hiver#traina norell#marvella#coty perfume#parfum coty#horst p. horst#ruth neumann#emeraude#bianchini

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

look for the name: BABETTE

vintage blue calico floral capelet prairie dress, c. 197o's

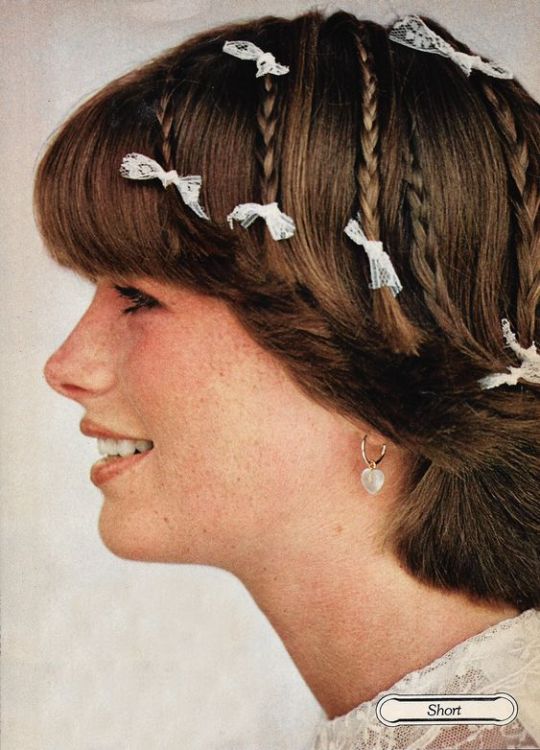

{hair} "new twists for holidays hair" for short hair, from just seventeen magazine (december 1978)

vintage white lucite beaded flower pearlized box purse w/ clear petal cut lid and twist handle, c. 195o's

coty "muguet des bois" eau de parfum

cecilie bahnsen x charles & keith "dahlia" recycled satin quilted and embroidered mary jane flats in ivory color

#babette#name#request#outfit#hope you like !#blue#cornflower#vintage#retro#prairie#dress#197o's#hair#just seventeen magazine#lucite#bag#coty#edp#perfume#cecilie bahnsen#footwear#mary janes#charles & keith#queue

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vintage Coty Miniature Paris De Coty Glass Perfume Bottle W Metal Case ebay 8TEN1944

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

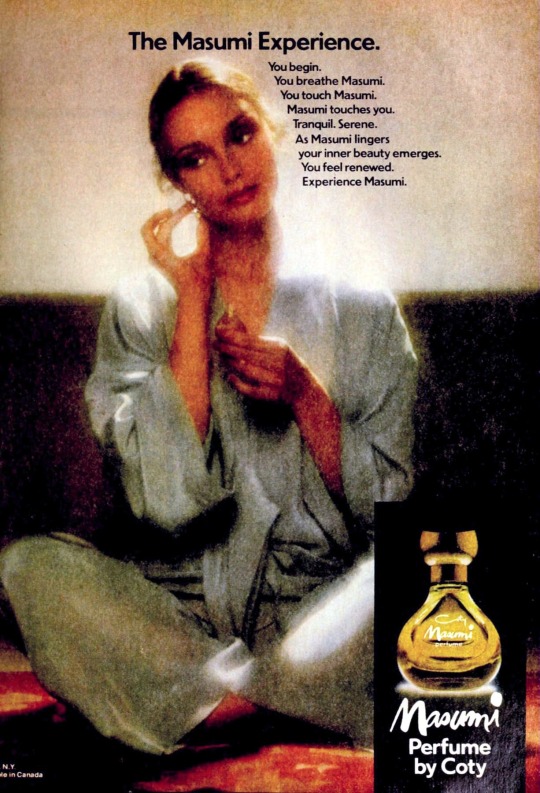

“Masumi” by Coty was first launched in 1967 and was a Chypre Floral fragrance. It had top notes of Palisander rosewood, bergamot, pineapple, and melon, middle notes of cardamom, rose and violet, and base notes of oakmoss, Virginia cedar, musk, sandalwood, amber and vanilla.

Coty said this of the fragrance:

“Masumi Coty was launched in 1967 as a floral – green – chypre fragrance. It is inspired by the Far East and emotions of bliss, serenity and calmness.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vintage Perfume Quick Takes

brief summaries for when I didn't have enough to write for a full review

F. Millot Crepe de Chine

Nose: Jean Desprez

Notes: aldehydes, bergamot, neroli, lemon, orange; carnation, lilac, iris, jasmine, rose, orange blossom, ylang-ylang, elemi; oakmoss, galbanum, heather, sandalwood, leather, benzoin, musk, patchouli, vetiver, cedar, amber

Goes on with a hit of boozy-sweet resins, and quickly fades into a fluffy, chintzy mixed floral, heavy on the rose. I find it forgettable.

It's supposed to be a bitter, sophisticated chypre; maybe I got a suboptimal sample or a bad nose day?

Evyan White Shoulders

notes: aldehydes, orange flower, green notes, peach, bergamot; gardenia, lilac, tuberose, jasmine, lily, lily-of-the-valley, iris, spices; civet, oakmoss, musk, sandalwood, benzoin

Your basic white floral. Smells good, though maybe a little too sweet and creamy for my taste; fades rapidly.

Guerlain Chant D'Aromes

Nose: Jean-Paul Guerlain

Notes: aldehydes, citrus, gardenia, plum; honeysuckle, jasmine, ylang-ylang, clove; heliotrope, vetiver, olibanum, benzoin, vanilla

This was a light, citrusy floral veil with a cuddly-soft drydown. There were some unusual herbal notes, almost like cooking herbs (thyme?). Delicate and pleasant but not too memorable.

Coty L'Aimant

Nose: Vincent Roubert

Notes: aldehydes, neroli, peach, bergamot; ylang-ylang, rose, jasmine, geranium, orchid; musk, sandalwood, vanilla, tonka, vetiver, cedar

This is a bit of formal glass-chandelier sparkle over the usual Coty powder-soft base. A milder, puff-powder version of the classic aldehydic floral. The powder certainly makes it easier to wear, but also less interesting.

It settles into pure powder, musky and sweet and very skin-like.

Guerlain Mouchoir de Monsieur

Nose: Jacques Guerlain

Notes: lavender, bergamot, lemon verbena; neroli, tonka, jasmine, patchouli, cinnamon, rose; vanilla, iris, amber, oakmoss

A wine-dark rose, somewhat tangy; that almost immediately falls into pale powder. Not too sweet, just smells clean and comfortable.

I must be missing most of the complexity because everyone else seems to smell lavender, vanilla, and animalics. I get very little of anything, maybe a little bit of the oakmoss spine or a touch of dry citrus, and clean soft powder.

Caron Tabac Blond

Nose: Ernest Daltroff

Notes: carnation, leather, linden; iris, ylang-ylang, vetiver; vanilla, musk, patchouli, cedar

Goes on with smoky, sweetened leather. a soft powdery landing. pleasant but not memorable. Basically Bellodgia with a leather top.

#perfume#fragrance#caron#guerlain#coty#evyan#f. millot#ernest daltroff#jacques guerlain#jean-paul guerlain#vincent roubert#jean desprez

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

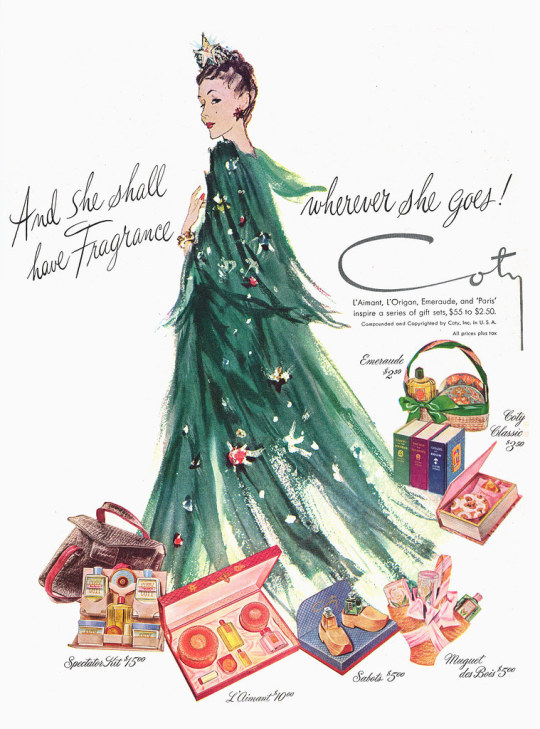

Publicités pour les parfums Coty

When you’re in love wear Muguet des Bois - 1940′s

And she shall have fragrance wherever she goes - Noël 1945

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coty • Paris • 1946

Would you like to know more? adtothebone.com/thats-hot-2

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The World’s First Oriental Fragrance

Launched in 1925 by Jacques Guerlain, Shalimar is widely considered the first, true, oriental perfume. But is it? Before we explore, let’s define what an oriental fragrance is.

What is an Oriental Fragrance?

The classic Oriental fragrance is composed of vanilla and/or vanillin (synthetic vanilla), tonka bean, patchouli, musks, resins, and amber.

There are also sub-categories of Oriental like Floral Oriental, Woody Oriental, and Spicy Oriental.

Amber Accord

Amber isn’t a single ingredient. It’s a collection of scents that together create the amber accord. The main ingredients are vanilla and/or vanillin, patchouli, tonka bean, and resins like benzoin and labdanum.

The Amber Accord smells warm, sweet, powdery, and animalic.

Amber is also a fragrance category, and it’s interchangeable with Oriental. In other words, any perfume labeled an Amber is, by definition, also an Oriental.

The Contender

In 1921, another perfumer named Francois Coty released an Oriental perfume named Emeraude. It was the signature scent of the legendary singer Billie Holiday.

Emeraude ticks all the correct boxes. It contains vanilla, tonka bean, amber, patchouli, and benzoin. It doesn’t contain musk, but amber is often musky or otherwise animalic-smelling.

Looking at the years the perfumes were launched, it seems obvious which is the older fragrance. But just to complicate matters, because it’s more fun that way, the House of Guerlain claims the true release date of Shalimar was also 1921.

Shalimar’s Not-So-Straight-Forward History

According to the fragrance House of Guerlain, Shalimar was originally released in 1921. The bottle was different from the bottle we’re familiar with today.

Perfume Intelligence has two perfume-bottle listings for Shalimar by Guerlain in 1921: one bottle is made by Wheaton Glassworks, the other by Cristalleries de Baccarat bottle design # 597. There are no photos of either bottle. (I can’t vouch for the validity of the Perfume Intelligence website.)

When Shalimar was re-released in 1925, Raymond Guerlain designed a new bottle for it. The modern bottle looks similar to Raymond Guerlain’s design.

Oriental/Amber Sisters

Both perfumes have citrus top notes, with Emeraude being the more citrusy of the two. Emeraude is a more subtle fragrance than Shalimar; it’s sweeter, more powdery, and less spicy. Shalimar is the bolder and richer of the two; it’s more sultry.

Both perfumes are warm, spicy and strongly vanilla. Both fragrances are marketed to women, but many men wear them. Don’t be restrained by labels. Wear what you love.

If Emeraude is the statuesque refined sister, Shalimar is the wild impetuous sister.

Emeraude

Only available in eau de cologne concentration

Far less expensive than Shalimar

Uses lesser-quality ingredients than Shalimar

Has been reformulated several times

Shalimar

Available in a variety of perfume concentrations

Is much more expensive than Emeraude

Uses better-quality ingredients than Emeraude

Has been reformulated at least once to substitute real animalics – musk and civet – with synthetic versions

So Which is the First?

The release date for Emeraude is easily provable by searching for perfume bottles from 1921. For Shalimar, perfume bottles from 1925 are easily found. Pre-1925 bottles of Shalimar aren’t so easy to find.

It’s quite possible that Shalimar’s first iteration didn’t sell well and there are no surviving bottles.

Unless more provable evidence turns up, Emeraude is the first, true, Oriental perfume. If they were both released in 1921, then the day and month of release needs to be noted to learn which is the older perfume.

Instead of calling Guerlain out, let’s just be grateful that these icons of perfume history are still made today and are available for purchase.

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Review: Hugo Boss XX Perfume for Women #fragrancereview

#youtube#hugoboss#coty hugobossxx Sexyfragrancesforwomen perfumes ladiesscent floralperfumes hugoboss

0 notes

Text

Knize Ten 100th Anniversary Review - Francois Coty & Vincent Roubert; 1924

One of the all-time greats - Knize Ten - turns 100 this year! #perfume

Perfume databases on the internet aren’t 100% accurate. And although many state that Knize Ten first appeared in 1924, it’s important to point out that some claim the launch date was 1925. However, I’m partial to big anniversaries on my YouTube channel, so I decided to go with the earlier date and take the opportunity to review this beloved classic in a recent episode of Love At First Scent.…

View On WordPress

#1924#2024#anniversary#classic#Francois Coty#Knize#Knize Ten#leather#Love At First Scent#masculine#perfume review#video#Vincent Roubert#vlog#vlogger#YouTube

0 notes

Video

youtube

ASPEN DICEN QUE ES UN CLON DE COOL WATER

0 notes

Text

Coty's beautiful & vintage L'Aimant cologne

0 notes

Photo

what would @bebemoon wear~ ?

alexander mcqueen “irere” collection shredded silk gown, rtw s/s 2oo3

costume originally worn by margot fonteyn as juliet in the ballet “romeo and juliet”

jil sander rtw a/w 2o22 heels

coty “la rose” eau de parfum

efff (vintage shop) sheer chiffon off-the-shoulder gown

harlot hands “flight of the moth” necklace w/ shell, stainless steel and various soft metals

sororité vintage la perla silk-blend white sheer boned bra, antique cream lace full skirt and pear strand waist belt

marina bychkova’s “cinderella” bjd enchanted doll w/ cast sterling silver corset, shoes and hair ornaments, c. 2oo9 (in lieu of a bag or whatever, just carry an intricate porcelain bjd under your arm, right ?)

servalan from “blake’s 7″ wearing a shredded one-shoulder black gown w/ white pearl beaded bra-top

#well ask and you shall receive.. eventually ^^'#mb#mine#looks#what i would wear#vintage#bebemoon aesthetic#alexander mcqueen#margot fonteyn#ballet#costume#jil sander#footwear#coty#perfume#efffshop#effy turner#harlothands#harlot hands#silver#pearls#necklace#jewellry#sororité#la perla#marina bychkova#enchanted doll#porcelain#doll#bjd

824 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vtg empty Chypre de Coty Gold Mini Perfume Bottle & Fitted orig box ebay 8TEN1944

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Historians are rarely challenged just for applying words like ‘woman’ and ‘man’ to the past; it would not inevitably cause a backlash to say that a historical figure wanted power, or grieved, or felt anger. A trans historian, though, is caught in the double-bind of the DSM-5. Our experiences and our desires are quite literally mad. We do not have the social license to see ourselves fractured and reflected in historical figures; we are standing in the wrong place to write. Put simply, if you foreclose trans readings, you foreclose trans writing. When we reflect on the similarities between our lives and those of historical figures, we are accused of spreading our social contagion to the dead. To read our own anamorphoses in a text, to communicate that to a cis academic establishment who have rendered our unqualified subjectivities unimaginable, we are forced to accuse historical figures of transness. And then, of course, we are chastised for pathologising them. For a trans historian, it is not viable to simply universalise our experiences of gender. In order to relate to historical figures’ gendered experiences in our writing in a way that is legible to cis readers, we have to assert that those figures were trans. There is a gap to be bridged, and the onus to bridge it falls on us…

Transmisogyny and anti-effeminacy were and are integral to the structure of patriarchy and therefore to cisness (or vice-versa). In ‘Monster Culture (Seven Theses)’, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen proposed a methodology for reading cultures: ‘from the monsters they engender’. In concluding this sketch of Byzantine cisness, I would like to attempt to apply this method. To monster a group or an individual is a violent act, and through examining the way transfemininity was monstered in Byzantium, we can begin to understand the shape of the violent regulation of gendered possibilities that constituted Byzantine cisness…

Synesius [of Cyrene] did not simply compare the image of the elegantly coiffed effeminate with the shiny dome of the soldier’s helmet; he went one step further, proclaiming that pretty hair was the give-away for hidden effeminacy. He rails against ‘effeminate wretches’ who ‘make a cult of their hair’, who he suggests engage in sex work not out of economic necessity but as an act of sex and gender exhibitionism, to ‘display fully the effeminacy of their

character’. Then, he goes on to say:

And whoever is secretly perverted, even if he should swear the contrary in the marketplace, and should present no other proof of being an acolyte of Cotys save only in a great care of his hair, anointing it and arranging it in ringlets, he might well be denounced to all as one who has celebrated orgies to the Chian goddess and the Ithyphalli.

The implication is clear: long, well kempt, perfumed and curled hair is not just hair, it is a signifier, one that signals total abnegation of manhood, and therefore of cisness. This demonstrates one of the mechanisms by which cisness was maintained and enforced in the Byzantine world. Relatively minor embodied gender transgressions, like too-long or too-pretty hair, could be linked to transfemininity and to sexual receptivity, the two farthest points from patriarchal manhood. That is not to say that this prevented people from committing such gender transgressions; rather that it made them risky, a weapon that could be used against you by anyone who wanted to do you harm. The other thing demonstrated by Synesius’ invective is the relationship between effeminacy, unmasculine vanity and presumed sexual receptivity. It would be tempting, based on the relationship Synesius draws between long beautiful hair and receptive anal sex, to suggest that the animating force of this antipathy is, if not homophobia, a narrower pre-modern equivalent. There is, however, a fantastically complicating detail in Synesius’ remark on the reasons such ‘effeminates’ engage in sex work: being sexually available is presented as an instrumental, rather than terminal value. In Synesius’ imagination, sex work is the means, but social recognition of the feminine gender of the sex worker is the end: to ‘display fully the effeminacy of their character’. The monster Synesius invokes to shore-up his own gender position, to guard his own cisness and his access to hegemonic masculinity, is an unambiguously transmisogynist fantasy. It is here that Byzantine cisness most sharply converges with twenty-first-century cisness.

‘Selective Historians’: The Construction of Cisness in Byzantine and Byzantinist Texts, Ilya Maude [DOI]

3K notes

·

View notes