#chekhov

Text

imagination (1963) - harold ordway rugg

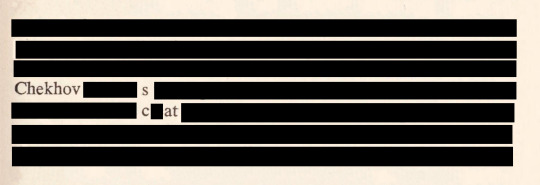

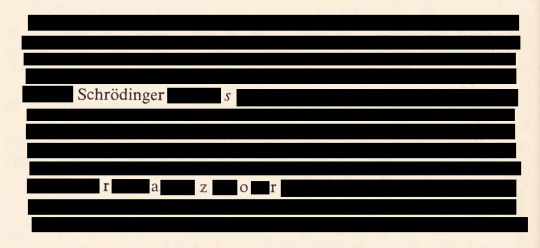

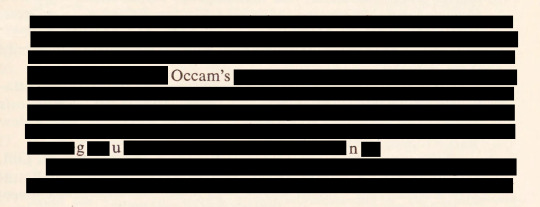

"chekhovs cat / schrödingers razor / occams gun"

#chekhov#schrodinger#occam#the three genders#hope everyone has a good halloweekend#and a good hallowtuesday#watched the 1979 nosferatu#it was silly#feel free to recommend more german films#anyway#blackout poetry#blackout poem#author#book#poetry

58K notes

·

View notes

Quote

Three o'clock in the morning. The soft April night is looking in at my windows and caressingly winking at me with its stars...

Anton Chekhov, from “Love”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

‘if you ever have need of my life, take it’ is such a metal line. you would think it’s from the seagull by anton chekhov or something and it is. it is from the seagull by anton chekhov.

#chekhov#the seagull#tagging this feels redundant after the actual contents of the post lol#me when the seagull by anton chekhov author of the seagull by chekhov#found in my drafts

183 notes

·

View notes

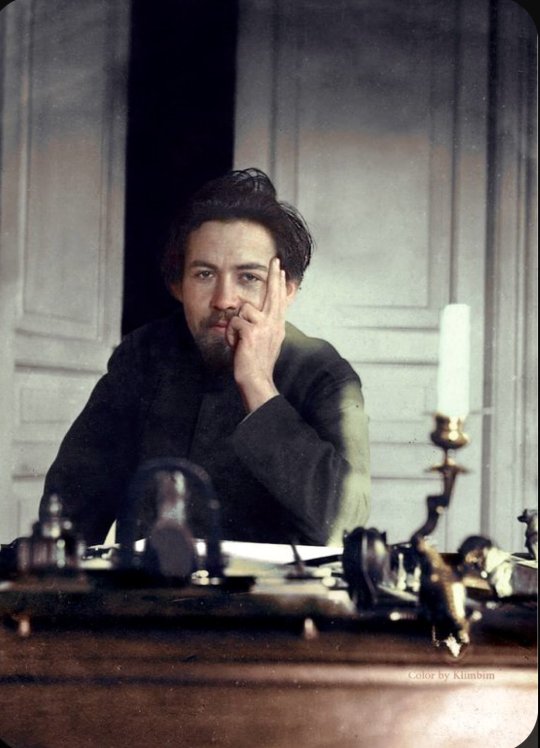

Text

We are lucky to be alive in the age of Andrew Scott, an actor of extraordinary breadth, skill and sensitivity, who can terrify as Jim Moriarty in Sherlock, make us fall in love (inappropriately) as the hot priest in Fleabag and cry in All of Us Strangers. He can also astonish, last year playing eight parts in a stage adaptation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. He recently became the first actor to win the UK Critics’ Circle awards for best actor on stage and screen in the same year. And his latest project, Ripley, is a beautiful and chilling adaptation of the Patricia Highsmith novel The Talented Mr Ripley, with Scott playing the lead, dominating all eight one-hour episodes. It’s been a wild, crowning year for the 47-year-old Irish actor. But in March his mother, Nora, died of a sudden illness; she is who Scott has credited as being his foremost creative inspiration. His grief is fresh and intense and for the first half of the interview it seems to swim just beneath the surface of our conversation.

“We go through so many different types of emotional weather all the time,” he says. “And even on the saddest day of your life you might be hungry or have a laugh. Life just continues.” We are in a meeting room in his management company’s offices, talking about his ability, in his work, to modulate between emotions, to go from happy to sad, confused to scared, all within a matter of seconds. How does he do it? Scott laughs. “I would say that I have quite a scrutable face — is scrutable a word? — which is good or bad depending on what you are trying to achieve. But my job is to be as truthful as possible in the way that we are, and I don’t think that human beings are just one thing at any particular time. It is rare that we have one pure emotion.”

It’s an approach that is particularly appropriate for the playing of Tom Ripley, an acquisitive chameleon who inveigles his way into the lives of others (in this case Johnny Flynn, as the careless and wealthy Dickie Greenleaf, and his on-off girlfriend Marge, played by Dakota Fanning). “Ripley is witty, he is very talented. That’s gripping, to watch talent. I can’t call him evil — it is very easy to call people who do terrible things evil monsters, but they are not monsters, they are humans who do terrible things. Part of what she [Highsmith] is talking about is that if you dismiss a certain faction of society it has repercussions, and Ripley is someone who is completely unseen, he lives literally among the rats, and then there are these people who are gorgeous and not particularly talented and have the world at their feet but are not able to see the beauty that he can see.”

The show was written and directed by Steven Zaillian, the screenwriter of Schindler’s List. It’s set in Sixties New York and Italy, and filmed entirely in black-and-white, its chiaroscuro aesthetic evoking films of the Sixties — particularly those of Federico Fellini — while also offering an alternative to Anthony Minghella’s saturated late-Nineties iteration that starred Matt Damon and Jude Law. This has a darker flavour. “I found it challenging,” Scott says, “in the sense that he’s a solitary figure and ideologically we are very different. So you have to remove your judgment and try to find something that is vulnerable.”

It was a tough shoot, taking a year and filmed during lockdown. Scott was exhausted at the end of it and had intended to take a three-month break, but delays meant that he went straight from Ripley into All of Us Strangers. “Even though I was genuinely exhausted, it was energising because I was back in London, I was getting the Tube to work, there was sunshine,” he says. “I found it incredibly heartful, that film, there were so many different versions of love … I feel that all stories are love stories.”

All of Us Strangers, directed by Andrew Haigh, is about a screenwriter examining memories of his parents who died when he was 12. In it Scott’s character, Adam, returns to his family home, where his parents are still alive and as they were back in the Eighties. Adam is able to walk into the memory and to come out to his parents, finding the words that were unavailable to him as a boy. Some of it was filmed in Haigh’s childhood home, and there was a strong biographical element for him and his lead. Homosexuality was illegal in the Republic of Ireland until 1993, when Scott was 16. He did not come out to his parents until he was in his early twenties. I ask if he was working with his own childhood experiences in the film. “Of course, so in a sense it was painful, to a degree, but it was cathartic because you are doing it with people that you absolutely love and trust. I felt that it was going to be of use to people and I was right, it has been. The reaction to the movie has been genuinely extraordinary — it makes people feel and see things, and that isn’t an easy thing to achieve.”

The film is also a tender and erotic love story between Scott’s character and Harry, played by the Irish actor Paul Mescal. The two found a real-life kinship that made them a delight to watch on screen and off it, as a double act on the awards circuit. “I adore Paul, he’s so, so … continues to be …” Scott pauses. “Obviously it’s been a tough time recently and he just continues to be a wonderful friend. It’s everything. The more I work in the industry, I realise, you make some stuff that people love and you make some stuff that people don’t like, and all really that you are left with is the relationships that you make. I love him dearly.”

Scott and Mescal were also both notable on the red carpet for being extraordinarily well dressed. Scott loves fashion and has a big, well-organised wardrobe that he admits is in need of a cull. “I don’t like having too much stuff. I really believe that everything we have is borrowed — our stuff, our houses, we are borrowing it for a time. So I am trying to think of people who are the same size as me so I can give some of it away, and that’s a great thing to be able to do.” One of his favourite labels is Simone Rocha. “I love a bit of Simone Rocha. What a kind, glorious person she is. I just went to her show.” Fashion, he says, is in his DNA. “My mother was an art teacher, she was obsessed with all sorts of design. She loved jewellery and jewellery design. Anything that is visual, tactile, painting, drawing, is a big passion of mine, so I have tremendous respect for the creativity of designers.”

Today Scott is wearing Louis Vuitton trousers and a cropped Prada jacket, dressed up because he is collecting his Critics’ Circle award for best stage actor for Vanya. I ask how it feels to have won the double, a historic achievement. “Ah …” he says, looking at the table, going silent, having just been so voluble. “I’m sorry …” His voice cracks a little. “It’s bittersweet.”

At the ceremony Scott dedicated the award to his mother, saying of her “she was the source of practically every joyful thing in my life”. Is it difficult for him to carry on working in the circumstances, I wonder. “Well, you know, you have to — life goes on, you manage it day by day. It’s very recent, but I certainly can say that so much of it is surprising and unique, and there is so much that I will be able to speak about at some point.”

He is looking forward, he says, once promotion for Ripley is over, to taking some time off, going on holiday, going back to Ireland for a bit. He has homes in London and Dublin. To relax he walks his dog, a Boston terrier, dressed down in jeans and a hoodie “like a 12-year-old, skulking around the city” or goes to art galleries on the South Bank — he was considering a career as an artist until he was 17 and got a part in the Irish film Korea. He goes to the gym every day, “not, you know, to get …” he says, flexing his biceps. “More that it’s good for the head.” He is social, likes friends, likes a party. When I ask if he gave up drinking while doing Vanya, which required him to be on stage, alone, every night for almost two hours, he looks horrified. “Oh God, no! Easy tiger! Jesus … Although I didn’t drink much, I did have to look after myself. But we had a room downstairs in the theatre, a little buzzy bar, because otherwise I wouldn’t see anybody, so I was delighted to have people come down.”

Scott was formerly in a relationship with the screenwriter and playwright Stephen Beresford and is currently single, although this is not the sort of thing he likes to talk about. He is protective of his privacy, not wanting to reveal where he lives in London, or indeed the name of his dog — but he swerves such questions with a gentle good humour.

He is famous on set for being friendly and welcoming, for looking after other people. “The product is very important, but most of my time is spent in the process, so I want that to be as pleasant and kind as possible. I feel like it is possible to do that, that it is an honourable goal.” He is comfortable around people, with an easy charm — no one I have interviewed before has said my name so many times. And although when we talk he sometimes seems reflective or so very sad, there are also moments when he is exuberant, silly, putting on accents. “I feel like, as a person, I am quite near my emotions. I cry easily and I laugh easily, and there is nothing more pleasurable to me than laughing.”

Scott was raised a Catholic and is no longer practising, but says his view about religion is “ever changing — I definitely have a faith in things that cannot be proved”. When he was younger and felt overwhelmed, just before or after an audition, he would go to the Quaker Meeting House in central London and sit in silence, something that made its way into the second series of Fleabag, in which Scott’s priest takes Waller-Bridge’s character to that same meeting house. “It’s just around here,” he says, standing up, looking out of the window at Charing Cross Road. “When Phoebe and I first talked, we met at the Soho Theatre. We talked about love and religion, we walked all around here. And I said, ‘This is a place I go,’ so we called in and there was no one there, so we sat in there and we talked. It was a really magical day.”

Scott says he sees all the different characters that he has played as versions of himself. “It’s like, ‘What would this version of me look like?’ rather than, ‘Oh, I’m going to be somebody else.’ You filter it through you, and you discover more about yourself. I think that is a very lucky thing to be able to do, to find out more about yourself in the short time that we are here.”

#Andrew Scott#Ripley#Nora Scott#Critics Circle#Vanya#Chekhov#West End#All of Us Strangers#Paul Mescal#Hot Priest#Fleabag#Phoebe Waller-Bridge#Jim Moriarty#Sherlock#Patricia Highsmith#The Talented Mr Ripley#Dickie Greenleaf#Marge Sherwood#Dakota Fanning#Johnny Flynn#Steven Zaillian#Matt Damon#Jude Law#Anthony Minghella#Simone Rocha#Louis Vuitton#Andrew Haigh#Korea#Stephen Beresford

69 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Cherry Orchard

#monochrome#garden#black and white photography#svart og hvit#noir et blanc#bianco e nero#schwarzweiß#blanco y negro#chekhov

226 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We shall find peace. We shall hear angels. We shall see the sky sparkling with diamonds.

- Anton Chekhov

St. Mary's Basilica, Krakow, Poland.

#anton chekhov#chekhov#quote#beauty#design#architrcture#church#basilica#st mary's basilica#krakow#poland#heaven#angels#christianity#spiritual

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

Samuel West - a selection of miscellaneous photographs

#because why tf not#samuel west#sam west#Chekhov#mr selfridge#Fleming#Hyde park on Hudson#Sunday brunch#I don’t actually know where all of these come from#but he’s so pretty#and I can’t do gifs#so occasionally I just post photos#because even if nobody reblogs it at least it was pleasant to put together

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

#literature#Pushkin#Lermontov#Gogol#ivan turgenev#Goncharov#fyodor dostoevsky#Tolstoy#Chekhov#Bunin#Gorky#Bulgakov#Nabokov#wojak

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

✍ Серьёзность человека обладающего чувством юмора, в сто раз серьёзней серьёзности серьёзного человека.

© А. П. Чехов

The seriousness of a person with a sense of humor is a hundred times more serious than the seriousness of a serious person. © A. P. Chekhov

#цитата#Чехов#литература#смыслы#мысли#позитив#на_заметку#quote#Chekhov#literature#meanings#thoughts#positive#on_mark#жизнь#психология#мотивация#motivation#творчество#life#русский тамблер#русский пост#русский текст#русский tumblr#русский блог#юмор#humor

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Do silly things. Foolishness is a great deal more vital and healthy than our straining and striving after a meaningful life.

Anton Chekhov

#book quotes#anton chekhov#short stories#russian literature#books and libraries#books and reading#Chekhov#bibliophile#life quotes

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

This openness to more — to truth beyond story, to beauty beyond certainty — is precisely what teaches us how to love the world more. With a deep bow to Chekhov as the master of this existential art, Saunders writes:

This feeling of fondness for the world takes the form, in his stories, of a constant state of reexamination. (“Am I sure? Is it really so? Is my preexisting opinion causing me to omit anything?”) He has a gift for reconsideration. Reconsideration is hard; it takes courage. We have to deny ourselves the comfort of always being the same person, one who arrived at an answer some time ago and has never had any reason to doubt it. In other words, we have to stay open (easy to say, in that confident, New Age way, but so hard to actually do, in the face of actual, grinding, terrifying life). As we watch Chekhov continually, ritually doubt all conclusions, we’re comforted. It’s all right to reconsider. It’s noble — holy, even. It can be done. We can do it. We know this because of the example he leaves in his stories, which are, we might say, splendid, brief reconsideration machines.

#Maria Popove#the Marginalian#George Saunders#uncertainty#literature#Chekhov#existential art#reexamination#reconsideration

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

20230819. 【🍋】

Summer, week 6: Live a life full of art.

Just about a month left before I enter a new academic year. A few personal projects are flooding in so trying to pick up the pace now! It’s all good fun, but when there are multiple things to do — all within a certain timeframe — it’s rather busy. I’m excited for all these opportunities though.

I’ve wrapped up some more books and now working through the rest of my old shelf. Also went to a wonderful exhibition which I enjoyed greatly!

☞ studygram

#studyblr#studyblr community#study inspiration#study motivation#study space#studyspo#archiblr#architecture studyblr#architecture student#bookblr#russian literature#chekhov#anton chekhov#dark academia#dark academia aesthetic#academia aesthetic#venetianwindow#astudentslifebuoy#problematicprocrastinator#starrystvdy#heyzainab#heypeachblossom

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Let things that happen onstage be just as complex and yet as simple as they are in life. For instance, people are having a meal, just having a meal, but at the same time, their happiness is being created, or their lives are being smashed up."

- Anton Pavlovich Chekhov

With that in mind, let's talk about the Shrek 2 dinner sequence.

No, seriously. While perhaps not as intricate and dramatic as Chekhov's Ivanov, which tells the story of a man's decline into depression through heartbreaking subtext in the dialogue between himself and his peers as he gradually alienates himself from them, the dinner sequence in Shrek 2, I believe, is a three-minute masterclass in a similar sort of storytelling to the one that characterizes many of Chekhov's dramatic works. Chekhov was a big advocate of the "show, not tell" principle, and the Shrek 2 sequence demonstrates a fabulous exercise in this sort of writing, assisted by genius camera angles. I unironically love this sequence and how much it can tell us about writing- it demonstrates a complex show of dramatic tension and subtext, pacing, character dynamics, and cinematography, while also progressing the wider story and balancing the drama with the Shrek franchise's style of humor- which is not an easy feat to pull off. I really want to talk about this sequence and dissect it, because it's honestly taught me a lot as a writer.

So for context, in case you haven't seen Shrek 2, Shrek, an ogre, and his wife Fiona are having dinner with Fiona's parents, the king and queen. Due to a magic spell, Fiona has been permanently transformed into an ogre after falling in love with Shrek- which she gladly accepts, but her parents do not. With them is Donkey, a comic relief character. Due to the curse, Fiona's parents locked her in a tower until her "true love" could rescue her- which, of course, turned out to be Shrek in the previous movie. We see in this sequence that Fiona's parents have different attitudes towards the couple; later on in the movie, it's revealed that her father was the Frog Prince, contributing to her parents' opinions on magic spells impacted by "true love's kiss."

So, onto the scene.

First, we get an establishing shot of Shrek at the table, which is zoomed out to show Fiona and her mother sitting on either side, and Fiona's father on the opposite end. Obviously, two characters on either side of a long table is an easy way to show they are opposed to each other. Although the characters haven't spoken yet, an uncomfortable mood is quickly established- Shrek's facial expression looks uneasy. Behind him is a stuffed hawk and a fireplace- perhaps a nod to the fact that ogres are seen as predators to be hunted with torches and pitchforks. On either side of Shrek are two candelabras; he is surrounded on three sides by fire and the lighting is primarily cast upon him. The hawk's talons are also pointed down directly at him, and the scene is lit in an ominous red light.

The next few shots establish all the conflicting moods that will be at odds during the scene. Queen Lilian is, if you will, attempting to be an "ogre ally." She attempts to be accepting towards Shrek and Fiona's decision, but is still clearly uncomfortable. King Harold, however, makes no attempt to hide his contempt. It's him and Shrek- again, seated at the opposite ends of the table- who will have the most direct conflict. (Perhaps this is a small detail, but Lilian and Harold are dressed in pink and blue, respectively- feminine- and masculine-coded colors that contrast with each other. This may reflect their adherence to conservative societal norms, specifically relating to gender roles and relationships.)

No dialogue has been spoken yet, and the conflict is still being established. We get a POV shot of Shrek's plate, consisting of escargot and multiple different kinds of utensils, after Shrek nervously picks at it. The composition of the plate and utensils is complex, elegant, and orderly, again highlighting that Shrek is out of place.

The silence is first interrupted as Shrek picks up a snail with his fingers and bites into it with a loud crunch. The first domino has fallen; Shrek foregoes the utensils to eat in a manner familiar to him, creating a marked contrast with the way we assume Fiona's family will eat. Afterwards, we have a shot of Harold looking even angrier; Shrek has broken a social norm. Shrek smiles with his mouth full; we get Lilian looking even more nervous as she eats her escargot with a fork, and Fiona drinks from a glass of water.

Fiona, who is unwillingly assigned the role of mediator between the two parties, belches after drinking the water- a behavior expected from Shrek. She excuses herself politely, which is understood as an attempt at keeping the peace. However, Shrek cracks a crude joke ("better out than in, I always say!"), and they both laugh as the second domino falls. Lilian and Harold look uncomfortable; Fiona laughing at Shrek's joke and displaying chemistry with him communicates that she is on Shrek's side, not theirs. Noticing their discomfort, Shrek and Fiona stop laughing and appear dejected.

The tension is built further as Donkey enters. Donkey plays up the comic relief the entire time, but also adds to the tension more than he diffuses it. While friendly, he's loud and messy, and while Lilian looks at him curiously, Harold treats him rudely, shouting "bad donkey; down!" Fiona again attempts to ease the tension, explaining that Donkey helped rescue her. Donkey proudly agrees, but then demands a bowl for himself from the waiter. Shrek facepalms and says "oh boy;" there is now another conflicting dynamic in the room. Donkey, who has no interest in conforming to social norms, heightens the tension as Shrek and Fiona attempt to appease Fiona's parents.

Another domino falls. Shrek drinks from the bowl of water given to him, which is supposed to be used to wash his hands. Fiona gets his attention, and dips her hands in the bowl to signify its purpose without making it obvious to her parents that Shrek doesn't know what the bowl is for. Shrek doesn't pick up on the hint, and attempting to be polite, compliments the Queen on the "soup," even using the spoon- once again, trying to conform to the cultural norms of Fiona's parents. However, this time, he's supposed to use his hands and not utensils, as opposed to the escargot, where he was supposed to use utensils and not his hands. The only lines exchanged in these few seconds are:

Fiona: "um, Shrek?"

Shrek: "Ohh, sorry. Great soup, Mrs. Q."

Fiona: "No no no, darling."

However, through the action and the subtext given from the background of the film, the audience knows the tension is heating up. While only a few lines of dialogue are exchanged, we know from the few seconds of the "soup" sequence that Shrek is having more difficulty conforming, Fiona is having more difficulty keeping the peace, and her parents are having more difficulty masking their discomfort. Donkey seems completely oblivious to the conflict, paradoxically heightening it through contrast.

Queen Lilian starts the first actual conversation of the scene, a minute and 22 seconds in. She asks Shrek and Fiona where they live. As the audience, we know that they live in a swamp, but Shrek and Fiona don't want to say that because they want to appease Fiona's parents. Fiona answers, "Shrek owns his own land." This carefully-calculated answer isn't a lie, but it's not the whole truth, either. "Land" could mean anything, and the idea that Shrek owns land is an attempt to present the idea that Shrek is assimilated into the dominant culture. As ogres are presented as second-class (or should we say Shrekond-class) citizens in the Shrek universe, the idea that Shrek owns land may communicate that he is wealthy and conventionally successful, and is able to climb the social ladder and provide Fiona with the life her parents wanted for her.

Shrek, still nervous but playing along with what Fiona has laid out for him, confirms that they live in an "enchanted forest, abundant with squirrels and cute little duckies." Again, this is an attempt to console FIona's parents. But Donkey, unaware of what's going on, interrupts with, "what? I know you ain't talking about the swamp!"

Another domino falls as Shrek attempts to silence Donkey, but Harold latches onto this line, instead of keeping up the crumbling façade that everyone else (sans Donkey) is trying to uphold. Sarcastically, he responds with "an ogre from a swamp? How original," as Donkey laps from his water bowl. Now that Fiona's parents have acknowledged Shrek and Fiona as "living in a swamp," it becomes even harder to diffuse tension, as this is something they find undesirable. Because Donkey has confirmed it, Shrek and Fiona also can't fall back on the "enchanted forest" excuse they used earlier; it also affirms the stereotype for Harold that ogres live in swamps. Through his “how original” line, Harold is commenting that Shrek is not assimilated and fits the mold of a stereotypical ogre- perhaps suggesting he believes him to fit other ogre stereotypes, such as being monstrous, crude, or aggressive. (Holy shit, that’s a really harsh line from him!)

Despite the fact that Harold is now fully committed to heightening the tension, Lilian still attempts to resolve it- deepening their own rift of conflict. She comments that it will be a "fine place to raise the children," trying to reconstruct the idea that Shrek and Fiona can still live the nuclear family life that she wants for her daughter. However, this is immediately shattered, as Shrek and Harold- shown again from opposite ends of the table- choke on their food in shock- Shrek because he and Fiona are not interested in having children at the moment, and Harold because he doesn't want his daughter having children with Shrek.

To recap, before the dinner, Shrek and Fiona shattered two of the King and Queen's expectations:

1. Fiona has married Shrek, an ogre.

2. Fiona is now an ogre herself.

However, at the dinner- a minute and 53 seconds in- they have shattered three more of their desires for Fiona's married life:

Shrek, Fiona's husband, cannot perform conformity through manners and etiquette.

Shrek and Fiona live in a swamp, and not somewhere expected for a prince and princess.

Shrek and Fiona are not currently interested in having children and raising a traditional nuclear family- and if they did have children, they would be ogres.

From here, the tension still keeps rising, and the scene is only a little over halfway through. We get another POV shot from Shrek's perspective, as he coughs up the spoon- the symbol of performing that etiquette- and it bounces across the table towards Harold. Fiona, Lilian, and Donkey all look at Shrek in surprise; Harold looks at him in disgust.

Shrek continues to express his discomfort while being polite, saying it's a bit early to be thinking about children. Harold makes no attempt to hide his prejudice, saying "indeed; I just started eating," blatantly implying that the idea of Shrek and Fiona having children revolts him. Lilian responds with an irritated "Harold!" and Fiona says "Dad, it's okay," but Shrek has refused to let go of the argument, feeling insulted. He responds with "what's that supposed to mean?", trying to force Harold to voice his prejudices expressly.

The argument is now in full swing. Harold responds to Fiona (while gesturing at Shrek with the spoon) with "for his type, yes;" Shrek answers angrily with "my type?" Harold hasn't yet explicitly voiced that he doesn't like Shrek because he's an ogre, but at this point, it's completely obvious. Donkey finally picks up on the tension and excuses himself to go to the bathroom, but returns quickly to the table as the main course is brought in. Harold and Shrek glare at each other from across the table as the background music picks up into a waltz and the camera shows the waiters walking around the table with an elaborate meal- the setting of an upscale royal dinner is more forcibly established, but Harold and Shrek are no longer interested in playing up appearances.

Lilian and Donkey see an opportunity to make one final attempt to diffuse tension with the arrival of the meal- Donkey jokes, "Mexican food, my favorite!" (despite the meal resembling a Medieval European-style feast) and Lilian encourages everyone to eat, which Donkey enthusiastically agrees to. However, Harold and Shrek refuse to let the argument go.

Harold violently grabs a lobster from the table, saying, "I expect any grandchildren from you would be..." and Shrek grabs his own plate, angrily responding, "ogres, yes." Shrek is the one to drop the word "ogre,” which everyone has mostly been avoiding this whole time (aside from Harold’s “ogre from a swamp” line). In this, he displays he's unashamed of the fact he and Fiona are ogres, a pointed insult towards Harold, who is clearly prejudiced against them but refuses to say so explicitly.

Lilian cuts in with a "not that there's anything wrong with that," and then a pointed, "right, Harold?" She's still trying to downplay the conversation and keep the peace, while wanting to communicate to Shrek and Fiona (especially Fiona) that she's not prejudiced against them, (even if she is, albeit to a lesser extent than Harold). Harold then makes an explicitly prejudiced statement relying on stereotypes of ogres- "No, no- that is, if you don't eat your own young!" while slicing through the lobster with his knife.

Fiona responds with a shocked, "Dad!" before Shrek fires his own retort- "we usually prefer the ones who have been locked away in a tower!" and tears apart the roast turkey on his side of the table, biting into it forcefully- a show of rejection against the etiquette he has been expected to display. As we know from previous context, this line is a thinly-veiled insult at Harold and Lilian, who had locked Fiona in a tower throughout her childhood and adolescence. Furthermore, Shrek is here communicating that Harold is a hypocrite- he criticizes Shrek's ability to be a parent, but also neglected his own daughter.

Fiona gives an angry "Shrek, please!", but Harold immediately picks up on the barb, responding with "I only did that because I loved her!" From there, the argument fully escalates, turning physical as a food fight breaks out. As both Shrek and Harold fully disregard manners and social etiquette, poor Lilian sadly remarks, "it's so nice to have the family together for dinner" with a distraught look on her face as food flies past her. The argument culminates in Shrek and Harold fighting over a roast pig and the characters all shouting each other's names in a last-ditch attempt to stop the fighting (and Donkey shouting his own for comic relief). As we get a final shot of the destroyed dinner scene, Fiona- who has attempted to mediate the argument this whole time- runs out without a word, as both Harold and Shrek give each other angry glances.

From here, the rest of the film unpacks and resolves the arguments built up in this short three-minute scene. What started as a quiet dinner quickly, but gradually, evolved into a full-blown argument about bigotry, societal norms, and family expectations- all themes that carry the character arcs of Shrek, Fiona, Lilian, and Harold. The genius about this scene is that the tensions were always there from the beginning; the majority of the conflict started before the actual physical fight- happening, as Chekhov said, as "complex and simple as in real life."

#writing#film analysis#shrek#shrek 2#chekhov#man those are weird tags to have together#long post#shrekhov???

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Irish star Andrew Scott has made history after becoming the first to win the best actor gong from both the film and theatre Critics’ Circle in the same year.

His one-man performance in Vanya, an adaption of Russian playwright Anton Chekhov’s family drama Uncle Vanya, secured him the theatre prize on Monday at Soho Place in London.

It comes after he was named actor of the year at the London Film Critics’ Circle for his lead role in Andrew Haigh’s moving drama All Of Us Strangers last month.

Collecting the prize at the Critics’ Circle Theatre Awards, Scott said about the arts: “A lot of people need it, I need it and we all do so the arts should be protected and they should be celebrated and they should be funded.

“So I just want to say thank you to the artists.”...'

#Andrew Scott#Vanya#Uncle Vanya#Chekhov#Critics Circle Theatre Awards#Andrew Haigh#All of Us Strangers

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

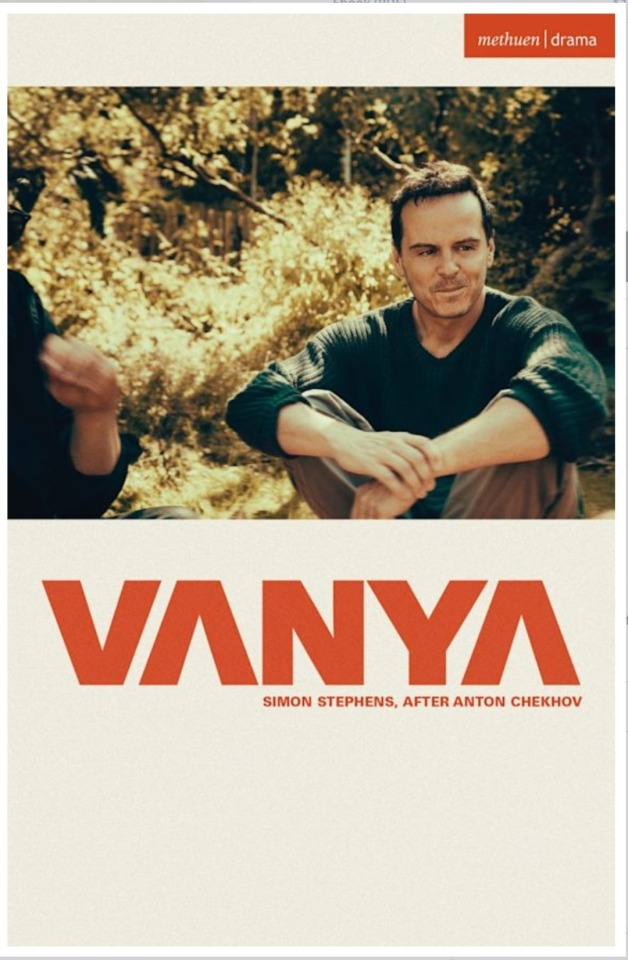

Anyone who's planning to see Vanya (after the October 9th release date) and wants to be familiar with the text, or saw it already and didn't get a copy in theater, but wants a souvenir, or just happen to be one of the many fans who won't get to see it (but totally aren't jealous and bitter about missing out) you can now pre-order a copy of the Vanya play text adapted by Simon Stephens, after Chekhov's Uncle Vanya , featuring Andrew Scott on the cover.

Available at Bloomsbury, Amazon and other book retailers on October 9th 2023, available for pre-order now.

Bloomsbury preorder

Amazon preorder

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

People don't notice whether it's winter or summer when they're happy.

Anton Chekhov

#chekhov#anton chekhov#quote#playwright#writer#literature#russian#happiness#seasons#winter#summer#bliss#life#mood

104 notes

·

View notes