#big data dystopia tag

Text

Also if you want some sources for my Old Person Yells At Cloud Tiktok tags there is a decent article with some credible academic sources here.

It’s not important to me that everyone never use TikTok because it has these qualities, but it is important that everyone engaging with it does so in an informed way. We all know things like slot machines or other highly rewarding things have the potential for addiction + people often set up strategies to harm reduce before engaging with them because of this. I don’t think the public narrative has extended that to social media in a thoughtful way, and there are certain platform types and feature types that can skew more towards being risky to use. Tiktok takes all of the riskiest features and smushes them into one platform, which is why I take issue with it so specifically.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

[// DATA TAGS: MOBILE NAV //]

Welcome to my semi-comprehensive tag map! Generally I try pretty hard to keep everything tagged appropriately for blacklisting/filing purposes so I can find stuff later. This is a list of tags I feel are most consistently used for various reasons or I plan on using. I am a big advocate for the curated dash experience, please blacklist tags if you’re not into them.

This remains a constant WIP, I’ll add new tags as I go.

[!// I try my best to make sure I tag any potentially sensitive/triggering content appropriately but stuff can be missed. Please let me know if you feel something needs to be tagged appropriately. //!]

[// CREATIVE STUFF //]

My Art - Artworks I’ve done (Art Account @Kerynean)

My Renders - 3D art stuff specifically.

My Writing - Writing I’ve done/Currently Working On

My Edits - Gaming-Related Edits (Screenshots/Gifs/etc.)

My Gifs - Gifsets I’ve made.

My Screenshots - My gaming screenshots/virtual photography.

My Modding - Personal Mod talk, wip progress etc.

My Mods - Mods I’ve released.

My OCs - Personal blorbos.

WIP - Any works in progress, can be modding or art etc.

[// PERSONAL TAGS //]

Kerytalk - Rambleposting/Personal Commentaries/WIP talk etc.

Keryplays - Videogame Adventures.

About Me - Personally relateable Content/Posts.

My Face - The extremely rare selfie.

Resources - Useful Stuff/Find Later Tag.

Memes - Funny Things containment Tag.

Audhd Things - Relevant or relateable to my Autism/ADHD wombo combo.

Note to Self - Reminders about things.

Ventposting- The rare venting post.

Straya - I'm Australian and we love to truncate words, and here's the Aussie tag.

SRB - Self-Reblog tag (usually for timezones)

Q - Queue-post tag (when I remember to use it)

[// GAMING (AND RELEVANT TAGS) //]

Cyberpunk 2077

Cyberpunk 2077 ✛ CP2077 Fanart ✛ CP2077 Spoilers ✛ PL Spoilers ✛ Phantom Liberty ✛ Cyberpunk Lore ✛ Jackie Welles ✛ OC: Venatrix ✛ Jackie x V ✛ Fem V ✛ Masc V ✛ Enby V

Baldur’s Gate 3

Baldur’s Gate 3 ✛ BG3 Fanart ✛ BG3 Spoilers ✛ DND Lore ✛ Karlach ✛ BG3 Venatrix ✛ Karlach x Tav

Mass Effect

Mass Effect ✛ Mass Effect: LE ✛ Femshep ✛ Garrus Vakarian ✛ Shakarian

Other Tags

Virtual Photography

Gaming Edit

[// MODDING //]

Cyberpunk 2077 Modding - Mod wip from myself and others, technical talk + resources etc.

Cyberpunk 2077 Mods - Mod releases for Cyberpunk 2077.

BG3 Modding - Mod wip from myself and others, technical talk + resources etc. for Baldur's Gate 3.

BG3 Mods - Mod releases for Baldur’s Gate 3.

[// SOCIAL COMMENTARY //]

PSA - Public Service Announcement (this is important, probably look at it).

Fandom Discourse - Any kind of meta-ish commentary on fandom.

Fuck Corpos - For all my spite against the capitalist machine.

This Has Been A Tag Rant - It’s a rant, but it’s in the tags (sorry).

Tech Dystopia - Active documentation of our slide into CP2077 setting (apparently).

Disabiliy / Ableism - I have disabilities so expect some of both.

LGBTQ+ / Gender - I’m not straight either. Also expect me yelling about how gender is a social construct frequently.

[// OC STUFF //]

OC: Venatrix - My canon Cyberpunk 2077 V, the gothic/rock girl OG.

BG3 Venatrix - It’s Ven but she’s a tiefling in the D&D universe now.

Vibes: Venatrix - Posts/Aesthetics etc. I feel relate to Ven.

[// MISC TAGS //]

GIF - Any post that contains a gif (if I miss one, please let me know) for filtering.

Polls - All tumblr polls.

Art - Art from others, contemporary and/or historical.

Writing - Anything I feel is writing relevant really.

History / Science / Space - I am a nerd for this shit, expect it.

Inspo - Stuff I find inspiring!

Fish Nonsense - Containment tag for my own aquarium stuff (not reblogged content).

#mobile nav#sorry this is long I just got it finished and I know it's weird with mobile#pls ignore#for the pinned later

1 note

·

View note

Text

tuesday again 6/29/21

i read part of a book, the reading section is no longer fallow, we have planted and sown some sort of crop

listening venus fly trap by MARINA. a dear mutual whose post i cannot find and i do not want to tag in case i am misquoting her called her latest lyrics “preachy” and i gotta agree? this one is almost but not quite a fun throwback to electra heart era. whereas that album was very much about watching “weaponized femininity” and a persona crumble around you, this is more of a mean-girl single designed to get your attention on the rest of the album. “why be a wallflower/when you can be/a venus fly trap” is an inherently delightful line.

undefined

youtube

because i take a week off from this project every december, one week’s listening gets doubled up. glass animals’ mama’s gun gets on here bc it is perfectly engineered to stick in the back of my brain. i love a layered, kind of cluttered instrumental backdrop. the chimey-chimes! the sad woodwind! i don’t know that i particularly care for the lyrics or the people in the internet arguing about whether this song is about drugs or schizophrenia (the band said it’s about drugs, don’t be terrible to people with schizophrenia)

undefined

youtube

reading here is a stab at the beginning of a post, bc i fully intended to finish this book sunday night and then. didn’t.

i’m trying to walk a fine line between pointing out things i find irritating and taking an older work for what it was at the time but tumblr is not known for its reading comprehension so i am belaboring some points and being more diplomatic with my word choice than if i were jawing about this book with friends. i read The Drowned World by JG Ballard as one of my first forays into the adult (shut up) fiction section at the library. there are some lines that have stuck in my brain for more than ten years, such as (describing sailing over a city under sixty feet of water) “...like a reflection in a lake that has somehow lost its original.” i’m a sucker for “sad man on the bleeding edge of civilization holes up in a once-grand building with looted bits and bobs”. i think it’s good set dressing and i love a poor little meow meow.

@morrak kindly offered me a pretty vintage hardcover that came in the mail a few weeks ago and i finally had time to crack it open. i draft these posts on sunday, and this sunday it comes to you from my phone in my landlord’s backyard, where a hammock really isn’t helping with the ninety-two degree heat and fifty-eight percent humidity. a good backdrop for reading about the earth remembering it used to mostly be a big swamp.

i typed a very long draft that ended up being mostly “wow kay you’re saying a novel written in the 60s is worried about the destruction of the world but in a dreamy and kind of sexist way with a tenuous relationship with reality at best?” yes. that’s just how old sci fi is sometimes and we can point out how parts of it don’t hold up for a modern audience while talking about the parts we do like.

for example, it takes a lot of its flavor and style from late-1800s harder scifi about hidden worlds/a changing world due to industrialization (think Journey to the Center of the Earth, or any novel about a secret paradise at the South Pole, or Erewhon). it is, instead, a softer scifi mostly concerned about the effects of living through a disaster that isn’t your fault and couldn’t be prevented, and what staring at constant ruin (no matter how beautiful!) and isolation does to a guy’s brain (as opposed to “harder” scifi like a lot of Verne’s work or Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem that are really interested in how future technology might realistically work). i personally don’t think it’s a meaningful remix of these early altered-world novels, or at least i personally don’t find it terribly compelling in this particular aspect. women in late-1800s scifi either don’t exist at all or exist to be rescued from primitive humans so the author could write about some cool guns killing people. Beatrice thedrownedworld is in fact a catalyst for part of the book, but she does not feel like a real person, whereas Robert thedrownedworld feels like most of the professors ive had. poor bea, trapped in a sixties novel only to look pretty, be negged, and serve as a psychosexual metaphor. i have a pet theory that if you fuck in an older dystopia (like older horror) you die, but i don’t really have enough data points to separate it from standard misogyny just yet.

but at the same time, it’s such an interesting example of an apocalypse that isn’t humans’ fault. the earth is just doing some fucked-up shit for a while, and we might as well go see what’s up. in a lot of earlier scifi, the earth is just doing some fucked-up shit in the polar regions and we might as well go see what’s up.

sidebar, bc i’m me: in late-1800s scifi there’s some fun brotherly love/camraderie among the protagonists that you could put an interesting queer reading on (ask me about my Professor Arronax-twentythousandleaguesunderthesea-is-trans-theory) but Robert thedrownedworld is extremely straight. also like most of the professors ive had.

this is a book i’m fond of for its place in my life at a particular time and some really good imagery. sometimes on a sunday afternoon you read a short novel that does an excellent job of telling the story it set out to tell, and that’s enough.

watching the L0ki show. d/isney for once did not queerbait me, i do find their budget and attention to detail in costuming and set dressing excellent, and i do love an unapologetically not very nice woman. from previous experience with this particular flavor of #content this particular company puts out, i do not think it will hold my interest for a full season. also i am unable to read TVA as anything but Tennessee Valley Authority but that’s a different post

playing fallow week due to NDA

making lots of cleaning and packing and move-prepping. bought a fuckton of future textile crimes at various yard sales, which need to be frozen bc im inherently suspicious of old yarn and i’ll be fucking damned if i bring carpet beetles or moths into a new place. bug-free zone in the new place goddamnit

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digimon Xros Wars Ep31 Liveblog

It’s time for the new arc! Featuring a lot of status quo changes! Today, Taiki and Shoutmon are looking for the rest of Xros Heart and get to see first-hand what the Bagra Army’s ideal new world looks like.

the new OP’s right at the start of the episode! fancy! it makes sense since they’ve gotta establish that this is a Big New Arc

oh no oh god it’s the snake lady Digimon that joins Nene later. i had all but forgotten about her until I saw her in a post while looking through the Xros Wars tag and my life was better for forgetting her. she’s painful to look at. actually this OP is a little rough too. and I think a higher percentage of episodes in this arc are painful to look at. ugh.

a cool montage of all of Shoutmon’s xrosses (up to X5B) and then a slick transition to showing the evolutions! that was cool!

and a little intro by Taiki and Shoutmon to remind everyone what’s happening

right off the bat, the team has a goal — track down the rest of Xros Heart! they’re probably in jail or something.

so because of time dilation, everyone staying in the human world for about a day means that a long time has passed in the Digital World. Taiki says a few months, but I always got the impression it was more around a year.

so this flower field is only deceptively nice looking right. like how we all live in a dystopia but it mostly looks normal.

Lilymon has her survival priorities straight

oh I remember this little green dragon. I think I was a fan of them?

so the 108 zones have been condensed down into 7 lands and a castle by the Bagra Army. it’s super mario. the land that Taiki and Shoutmon are currently in, despite being covered in flowers, is Dragon Land. so the zones are now sorted by Digimon species...? sounds like the kind of arbitrary separation an antagonist would do.

don’t tell me the enemies are actually going to believe that the kid with flowers on his head is actually a Digimon basically called “Flowermon”

ah, the evolution doesn’t work on command. well, Omegamon did say that they’d have to remember their bonds with their friends for it to work.

apparently Kiriha’s army, Blue Flare, has still been going strong this whole time. I guess a cutthroat guy like him would fare well in a cutthroat world, at the expense of nice things like caring. I imagine Nene’s been working behind the scenes, and not going out on attacks like Kiriha, since her specialty is espionage?

the data of those who have fallen is being used to power something...??

Lilithmon and Blastmon have been effectively replaced by the 7 land bosses, lol. if I remember right, I think little “dame da” is their boss now?

oh I had kinda figured that when Bagramon said that the 7 death generals were gathering it was going to be a literal, physical gathering but I guess it’s just a zoom call

so Kiriha was trying to defeat the Dragon Land’s boss but then he *ganon voice* died. but then Taiki saved him by pulling him into a hole in the side of the dirt wall the land boss made.

Dragomon built all of these tunnels?! that must’ve taken ages!

I know that Kiriha’s talk about strength and weak Digimon like Dragomon being losers is important to his character development but I am just getting the teensiest bit sick of it. be nice to Dragomon you’d be dead without them. if I remember right, though, Dragomon continues being a fan of Blue Flare despite this and begs to join the team.

he doesn’t say it but you get the feeling that when Kiriha says that Taiki isn’t going to stand a chance in this tough new world, it seems like he means Taiki’s ideals of helpfullness and caring aren’t going to carry him through this time. this won’t be the case, obviously — it’s like Tactimon said before, Taiki’s ideals are dangerous to the Bagra Army.

and now Kiriha is insulting Dragomon again because there’s lava chasing them. Shoutmon comes right to Dragomon’ defense, though, and even swoops in to save Dragomon from the lava. this is a really good example of how Shoutmon has grown throughout the series — way back during the Island Zone, he got upset at the idea of Digi Xrossing with a weak Digimon like ChibiKamemon, but now he’s here risking his life for a weak Digimon.

and that act of kindness is letting him digivolve again!

hmm... Dragomon’s voice is starting to sound familiar... I wonder...? OK no not a voice actor I’ve heard before

FL,DSMFN Kiriha is genuinely psyched to see something cool like an evolution

idk why but I’m a sucker for heroes gently setting down someone they saved and then rushing off in a burst of incredible power. i guess it’s like, the combination of protecting someone and raw strength. and using that raw strength to protect.

& then rather than criticizing it for being a “coward’s” strategy, OmegaShoutmon actually incorporates Dragomon’s penchant for digging tunnels into his fighting style! it also shows how Shoutmon is usually used to being digi xrossed and incorporating his friend’s styles and abilities into his own fighting style.

and now the fight is going bad again but that’s a tale for later

oh are we finally getting more information on the Digimon in the Data Collections rather than (what looks like) a not-sequiter from the Monitamon

i didn’t actually get a chance to listen to it closely before so I’ve gone back to listen to the new OP. it’s good but I liked the other one better.

The members of Xros Heart are getting executed next time?! Huh. OK.

#digimon#xros wars#fiftytenlive#xros31#it seems that this arc is sometimes considered a new season? idk#im not resetting the episode count until hunters.#xw liveblog 21

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Life’s Code: Blockchain and the Future of Genomics

In an era of hotly contested debates surrounding data ownership, privacy and monetization, one particular piece of data could be said to be the most personal of all: the human genome.

While we are 99.9 percent identical in our genetic makeup across the species, the remaining 0.1 percent contains unique variations in code that are thought to influence our predisposition toward certain diseases and even our temperamental biases — a blueprint for how susceptible we are to everything from heart disease and Alzheimer’s to jealousy, recklessness and anxiety.

2018 offered ample examples of how bad actors can wreak havoc with nefarious use of even relatively trivial data. For those concerned to protect this most critical form of identity, blockchain has piqued considerable interest as a powerful alternative to the closed architectures and proprietary exploits of the existing genomics data market — promising in their stead a secure and open protocol for life’s code.

Encrypted chains

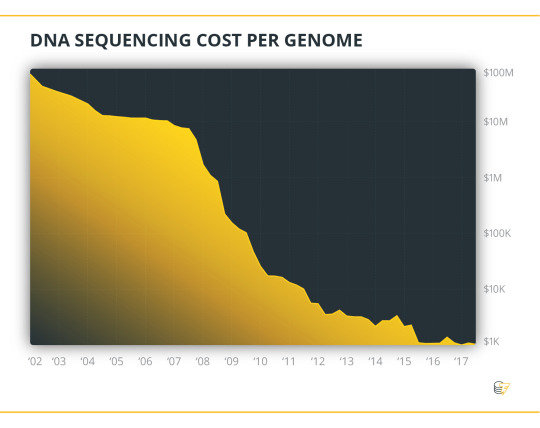

Sequencing the human genome down to the molecular level of the four ‘letters’ that bind into the double-stranded helices of our DNA was first completed in 2003. The project cost $3.7 billion and 13 years of computing power. Today, it costs $1,000 per unique genome and takes a matter of days. Estimates are that it will soon cost as little as $100.

As genomic data-driven drug design and targeted therapies evolve, pharmaceutical and biotech companies’ interest is expected to catapult the genomics data market in the coming years, with a forecast to hit $27.6 billion by 2025.

If the dataset of your Facebook likes and news feed stupefactions has already been recognized as a major, monetizable asset, the value locked up in your genetic code is increasing exponentially as the revolution in precision medicine and gene editing gathers pace.

Within the past year, unprecedented approvals have been given to new gene therapies in the U.S. One edits cells from a patient's immune system to cure non-Hodgkin lymphoma; another treats a rare, inherited retinal disease that can lead to blindness.

Yet, here’s the rub.

Genomics’ unparalleled potential to trigger a paradigm shift in modern medicine relies on leveraging vast datasets to establish correlations between genetic variants and traits.

Generating the explosion of big genomic data that is still needed to decode the 4-bits of the living organism faces hurdles that are not only scientific, but ethical, social and technological.

For many at the edge of this frontier, this is exactly where Nakamoto’s fabled 2008 white paper — and the technology that would come to be known as blockchain — comes in.

Cointelegraph spoke with three figures from the blockchain genomics space to find out why.

Who owns your genome? Resurrecting the wooly mammoth… and blockchain

For Professor George Church, the world-famous maverick geneticist at Harvard, the boundaries between technologies in and out of the lab are porous. Having co-pioneered direct genome sequencing back in 1984, a short digest of his recent ambitions include attempts to resurrect the long-extinct mammoth, create virus-proof cells and even to reverse aging.

He has now placed another bleeding-edge technology at the center of the genomics revolution: blockchain.

Last year, Church — alongside Harvard colleagues Dennis Grishin and Kamal Obbad — co-founded the blockchain startup Nebula Genomics. Church had been trying for years to accelerate and drive genomic data generation at scale. He had appealed to volunteers to contribute to his nonprofit Personal Genome Project (PGP) — a ‘Wikipedia’ of open-access human genomic data that has aggregated around 10,000 samples so far.

PGP relied on people forfeiting both privacy and ownership in pursuit of advancing science. As Church said in a recent interview, mostly they were either the “particularly altruistic,” or people concerned with accelerating research for a particular disease because of family experiences.

In other cases, as cybersecurity expert DNABits’ Dror Sam Brama told Cointelegraph, it is the patients themselves who generate the data and are “sick enough to throw away any ownership and privacy concerns”:

“The very sick come to the health care system and say, ‘We'll give you anything you want, take it, we’ll sign any paper, consent. Just heal us, find a cure.’”

The challenge is getting everybody else. While no one knows exactly how many people have had their genomes sequenced to date, some estimates suggest it is around one million.

Startups like Nebula and DNABits propose that a tokenized, blockchain-enabled ecosystem could be the technological tipping point for onboarding the masses.

By allowing people to monetize their genomes and sell access directly to data buyers, Nebula thinks its platform could help drive sequencing costs down “to zero or even offer [people] a net profit.”

While Nebula won’t subsidize whole genome sequencing directly, a blockchain model would allow interested buyers — say, two pharmaceutical companies — to pitch in the cash for someone’s sequence in return for access to their data.

Tokenization opens up the flexibility and granular consent for enabling different scenarios. As Brama suggested, a data owner could be entitled to shares in whichever drug might be developed based on the research that they have enabled or be reimbursed for their medical prescription in crypto tokens. Contracts would be published and hashed, and reference to the individual’s consent recorded on the blockchain.

Genomic dystopias

Driving and accelerating data generation is just one part of the equation.

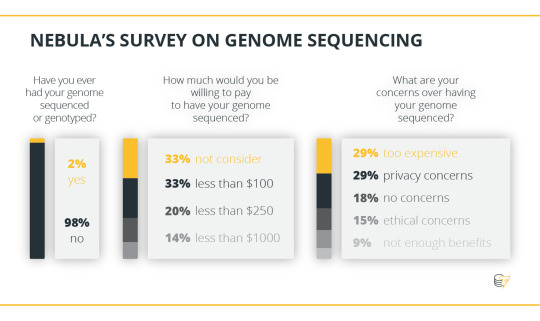

Nebula ran a survey that found that, rather than simply affordability, privacy and ethical concerns eclipsed all other factors when people were asked whether or not they would consider having their genome sequenced. In another study of 13,000 people, 86 percent said they worried about misuse of their genetic data: over half echoed fears about privacy.

These concerns are not simply founded in the dystopian 90s sci-fi of Hollywood — think Gattaca’s biopunk imaginary of a future society in the grips of a neo-eugenics fever.

As Ofer Lidsky — co-founder, CEO and CTO of blockchain genomics startup DNAtix — put it:

“Once your DNA has been compromised, you cannot change it. It’s not like a credit card that you can cancel and receive a new one. Your genetic code is with you for all your life […] Once it’s been compromised, there’s no way back.”

Data is increasingly intercepted, marketized and even weaponized. Sequencing — let alone sharing — your genome is perhaps a step further than many are willing to take, given its singularity, irrevocability and longevity.

DNABits’ Brama gave his cybersecurity take, saying that:

“The consequences are very difficult to imagine, but in a world [in which] people are building carriers like viruses that will spread to cells in the body and edit them — it’s frightening, but in fact, all the building blocks are already there: genome sequencing, breaches of data, gene editing. People are now working to fix major health conditions using gene editing in vivo. But we should assume that every tool out there will eventually also get into the wrong hands.”

He added, “We're not talking about taking advantage of someone just for one night with GHB or some other drug” — this would impact the rest of an individual’s life.

This April, on the heels of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, news broke that police detectives had mined a hobbyists’ genealogy database for fragments of individuals’ DNA they hoped would help solve a murder case that had gone cold for over thirty years.

Law enforcement faced no resistance in accessing a centralized store of genetic material that had been uploaded by an unwitting public. And while many hailed the arrest of the Golden State Killer through a tangle of DNA, others voiced considerable unease.

This obscurity of access has implications beyond forensics. While Brama’s dystopia may be some way off, today there are concerns about genetic discrimination by employers and insurance firms — the latter of which is currently only legally proscribed in a partial way. Grishin echoed this, noting that in the U.S., “you can be denied life insurance because of your DNA.”

This May, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission opened a probe into popular consumer genetic testing firms — including 23andMe and Ancestry.com — over their policies for handling personal and genetic information, and how they share that data with third parties.

23andMe and Ancestry.com represent a recent phenomenon of so-called direct-to-consumer genetic testing, the popularity of which is estimated to have more than doubled last year.

These firms use a narrower technique called genotyping, which identifies 600,000 positions spaced at approximately regular intervals across the 6.4 billion letters of an entire genome. While limited, it still reveals inherently personal genetic information.

The highly popular 23andMe home genotyping kit — sunnily packaged as “Welcome to You” — promises to tell people everything from their ancestral makeup to how likely they are to spend their nights in the fretful clutches of insomnia. The kit comes with a price tag as low as $99.

This July, the world’s sixth largest pharmaceutical company, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), invested $300 million in a four-year deal to gain access to 23andMe’s database, and the testing firm is estimated to have earned $130 million from selling access to around a million human genotypes, working out at an average price of around $130. By comparison, Facebook reportedly generates around $82 in gross revenue from the data of a single active user.

Battle-proof, anonymized blockchain systems for the genomics revolution

In this increasingly opaque genomics data landscape, private firms monetize the genotypic data spawned by their consumers, and sequence data is fragmented across proprietary, centralized silos — whether in the unwieldy legacy systems of health care and research institutions or in the privately-owned troves of biotech firms.

Bringing genomics onto the blockchain would allow for the circulation that is needed to accelerate research, while protecting this uniquely personal information by keeping anonymized identities separate from cryptographic identifiers. Users remain in control of their data and decide exactly who it gets shared with and for which purposes. That access, in turn, would be tracked on an auditable and immutable ledger.

Grishin outlined Nebula’s version, which would place asymmetric requirements on different members of the ecosystem. Users would have the option to remain anonymous, but a permissioned blockchain system with verified, validator nodes would require data buyers who use the network to be fully transparent about their identity:

“If someone reaches out to you, it shouldn't be just a cryptographic network ID, but it should say this is John Smith from Johnson & Johnson, who works, say, in oncology.”

Grishin added that Nebula has experimented with both Blockstack and the Ethereum(ETH) blockchain but has since decided to move to an in-house prototype, considering the 15 transactions-per-second capacity of Ethereum to be insufficient for its ecosystem.

DNABits’ Brama, also committed to using a permissioned system, proposed using “the simplest and most robust form of blockchain — i.e., a Bitcoin-type network.”

“The more powerful and the more capable engine that you use, the larger the surface attack.”

Lie-proofing the blockchain

23andMe is said to store around five million genotype customer profiles, and rival firm Ancestry.com around 10 million. For each profile, they collect around 300 phenotypic data points — creating surveys that aim to find out how many cigarettes you (think) you’ve smoked during your lifetime or whether yoga or Prozac was more effective in managing your depression.

A phenotype is the set of observable characteristics of an individual that results from the interaction of his or her genotype with their environment. Generating and sharing access to this data is crucial for decoding the genome through a correlation of variants and traits. But as Grishin notes, being largely self-reported, the quality of much of the existing data is uncertain, and a tokenized genomics faces one hurdle in this respect:

“If people will be able to monetize their personal genomic data, then you can imagine that some people might think, ‘If I claim to have a rare condition, many pharma companies will be interested in buying access to my genome’ — which is just not necessarily true. The value of a genome is kind of difficult to predict and it's not correct to say that if you have something rare, then your genome will be more valuable. In fact many studies need a lot of control samples that are kind of just normal.”

Education can help make people aware that they won’t be making any more money by lying and that a middle-of-the-road genome might be just as interesting for a buyer as an unusual one. But Grishin also noted that a blockchain system can offer unique mechanisms that deter deception, even where education fails:

“Blockchain can help to create phenotype surveys that detect incorrect responses or identify where an individual participant has tried to lie. And this can be combined with blockchain-enabled escrow systems, where, for example, before you participate in a survey, you have to deposit a small amount of cryptocurrency in an escrow wallet.”

If conflicting responses indicate that someone has tried to lie about their medical condition, then their deposit could be withheld in a way that is much easier to implement within a blockchain system than compared to one using fiat currencies.

2018: Viruses and chromosomes hit the blockchain

Even with just a fraction of the population on board, given the data-intensivity of the body’s code, a tsunami of sequence is already flooding the existing centralized stores.

The complex, raw dataset of a single genome runs to 200 gigabytes: In June 2017, the U.S. National Institute of Health’s GenBank reportedly contained over two trillion bases of sequence. One of the world’s largest biotech firms, China’s BGI Genomics, announced that same month that it planned to produce five petabases of new DNA in 2017, increasing each year to hit 100 petabases by 2020.

In his interview with Cointelegraph, Lidsky proposed that the raw 200 gigabyte dataset is unnecessary for analysts, emphasizing that initial genome sequencing is read multiple times “say 30 or 100 times,” to mitigate inaccuracies. Once it’s combined, he explained, “the size of the sequence is reduced to 1.5 gigabytes.” This still requires significant compression to bring it to the blockchain. As a reference, the average size of a transaction on the Bitcoin (BTC) blockchain was 423 kilobytes, as of mid-June 2018.

Average transaction size on the Bitcoin blockchain, 2014-18. Source: TradeBlock.com

In June, DNAtix announced the first transfer of a complete chromosome using blockchain technology — specifically IBM’s Hyperledger fabric. Lidsky told Cointelegraph the firm had succeeded in achieving a 99 percent compression rate for DNA this August.

Nebula, for its part, envisions that even on a blockchain, data transfer is unnecessary and ill-advised, given the unique sensitivity of genomics. It proposes sharing data access instead. The solution would combine blockchain with advanced encryption techniques and distributed computing methods. As Grishin outlined:

“Your data can be analyzed locally on your computer by you just running an app on your data yourself […] with additional security measures in place — for example, by using homomorphic encryption to share data in an encrypted form.”

Grishin explained that homomorphic techniques encrypt data but ensure that it is not “nonsensical” — creating “transformations that morph the data without disturbing it”:

“The data buyer doesn't get the underlying data itself but computes on its encrypted form to derive results from it. Code is therefore being moved to the data rather than data being moved to researchers.”

Encrypted data can be made available to developers of so-called genomic apps — something that Nebula, DNAtix and many other emerging startups in the field all propose as one means of providing users with an interpretation of their data. They could also provide a further source of monetization for researchers and other third-party developers.

But is ‘outsourcing’ genomic interpretation to an app that simple? The decades-old health care model referred patients to genetic counselors to go over risks and talk through expectations, helping to translate what can be bewildering and often scary results.

Consumer genetic testing firms have already been accused of leaving their clients “with lots of data and few answers.” Beyond satisfying genealogical curiosity and interpreting a range of ‘wellness’ genes, 23andMe can reveal whether you carry a genetic variant that could impact your child’s future health and has — as of 2017 — even been authorized to disclose genetic health risks, including for breast cancer and Parkinson’s.

Blockchain may not fare much better when it comes to leaving individuals in the dark, faced with the blue glow of their computer screens. Nebula and DNAtix are both considering how to integrate genetic counselors into their ecosystems, and Grishin also proposed that users would be able to “opt in” to whether they really want to “know everything,” or only want “actionable” insights — i.e., things that modern medicine can address.

Blockchain and big pharma

Prescription drug sales globally are forecast to hit $1.2 trillion by 2024. But closing the feedback loop between pharmaceuticals and the millions of people who take their pills each and every day still faces significant hurdles.

Drug development relies on correlating and tracking the life-cycle of medical trials, genetic testing, prescription side effects and longer-term effects relating to lifestyle; tokenization can incentivize individuals and enterprises to share data that is generated across multiple streams. As Brama outlined:

“Lifestyle data comes from wearables, smartphones, smart homes, smart cities, purchasing, commercial interactions, social media, etc. Another is carried by everyone, and that's our genome. The third is clinical and health-condition data generated in the health care system.”

Brama used the analogy of a deck of cards to explain how blockchain could be the key to starting to bring this data into connection, all the while protecting data owners’ anonymity.

An individual can hold an unlimited number of unique addresses in their digital wallet. Going into a pharmacy to purchase a particular drug — say, vitamin C, stamped with a QR code — would generate a transaction for one of these addresses. A visit to a family doctor might generate a further hash for a diagnosis on your electronic medical record (EMR) — say, a runny nose. This transaction goes between the caregiver and another wallet address.

A user might choose to put the correlation between transactions for their different wallets on the blockchain and make it public for people to bid on the underlying data. Or, they might keep the correlation off-chain and send proof only when, say, an insurance firm or research institute advertises to users who have a particular set of transactions:

“You hold the deck. You look at the cards, you decide if you say, if you don't say. And you can put them on the table and let everyone see, or you can indicate privately that you actually have these. It really leaves the choice and the implementation up to you.”

Biotechnological frontiers

Professor Church has made an analogy that likely rings bells for anyone plugged into the crypto and blockchain space, saying that “right now, genome sequencing is like the internet back in the late 1980s. It was there, but no one was using it.”

Blockchain and the vanguard of genomic research have perhaps come closer to each other than ever before. Now that the DNA in our cells is understood as a life-long store of information, a new and disruptive technology is needed to securely and flexibly manage the interlocking networks of the body’s code.

The advent of genomics raises questions that cannot be settled by science alone. For all of our interviewees, blockchain could be just the key to creating the equitable and transparent means of ownership and circulation that would ensure these helices of raw biomaterial don’t spiral out of control.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

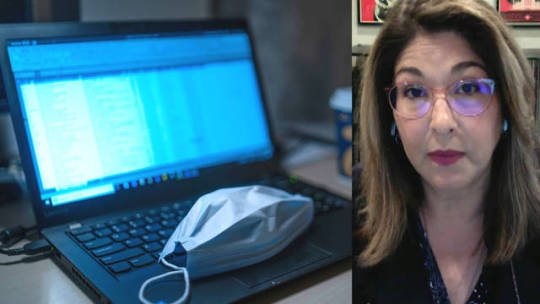

May 13, 2020 Screen New Deal: Naomi Klein on How Companies Like Google Plan to Profit in High-Tech COVID Dystopia

Screen New Deal

“What this, what I’m calling a “Screen New Deal,” really does is treat this period of isolation not as what we have needed to do in order to save lives — this is what we thought we were doing, right? — flattening the curve, but rather — and Eric Schmidt has said this elsewhere. He said it in April in a video call with the Economic Club of New York. He described what was happening now as a “grand experiment in remote learning.” So, all the parents out there who are listening or watching, you’ve been struggling with supporting your kids on Google Classroom and Zoom calls, and you thought you were just trying to get through the day. Well, according to Google, you’ve been engaged in a “grand experiment in remote learning,” where they are getting a great deal of data and figuring out how to do this permanently, because they actually believe this is a better way of educating kids, or at least, and coming back to our earlier conversation, a more profitable way.

So, I think we’re going to see very incomplete so-called solutions, and solutions obviously that massively benefit private tech interests. And we’re not having a discussion about, “Well, look, if it is true that we are going to need to be spending more time in our homes, and if it is true that access to technology is a lifeline, then should we be treating the internet as a commons, as a public utility, that we govern, that is governed by our regulations and by democracy?” As soon as you outsource the solutions to Eric Schmidt, who still has $5.3 billion in Alphabet shares, which is the company that owns Google, and who has holdings in all kinds of these tech companies, they are not going to put those public interest questions on the table.

And what we’re being sold now, whether with the idea that everything is going to be solved with more surveillance and an app or remote learning and telehealth, is really taking the humans out of the equation. Right? It is humans who are setting up these systems. It is humans, like whether it is the teachers in their homes or the parents in their homes, who are helping students learn right now. It isn’t just Google Classroom that is doing it. But humans are being erased from this story. And we aren’t hearing the kinds of human solutions that, with proper control over good technology, we could actually come up with some viable models here.”

Transcript READ MORE https://www.democracynow.org/2020/5/13/naomi_klein_coronavirus_tech_privacy_surveillance

coronavirus counting coup -

land mines for lungs,

watch one’s steps -YOU!

price tag

surveillance state

sticker-price

blues

Under Cover of Mass Death, Andrew Cuomo Calls in the Billionaires to Build a High-Tech Dystopia

May 8 2020 The Intercept

“It has taken some time to gel, but something resembling a coherent Pandemic Shock Doctrine is beginning to emerge. Call it the “Screen New Deal.” Far more high-tech than anything we have seen during previous disasters, the future that is being rushed into being as the bodies still pile up treats our past weeks of physical isolation not as a painful necessity to save lives, but as a living laboratory for a permanent — and highly profitable — no-touch future.

As chair,[Eric] Schmidt, who still holds more than $5.3 billion in shares of Alphabet (Google’s parent company), as well as large investments in other tech firms, has essentially been running a Washington-based shakedown on behalf of Silicon Valley. The main purpose of the two boards is to call for exponential increases in government spending on research into artificial intelligence and on tech-enabling infrastructure like 5G — investments that would directly benefit the companies in which Schmidt and other members of these boards have extensive holdings.

It’s a reminder that, until very recently, public pushback against these companies was surging. Presidential candidates were openly discussing breaking up big tech. Amazon was forced to pull its plans for a New York headquarters because of fierce local opposition. Google’s Sidewalk Labs project was in perennial crisis, and Google’s own workers were refusing to build surveillance tech with military applications.

Now, in the midst of the carnage of this ongoing pandemic, and the fear and uncertainty about the future it has brought, these companies clearly see their moment to sweep out all that democratic engagement. To have the same kind of power as their Chinese competitors, who have the luxury of functioning without being hampered by intrusions of either labor or civil rights.

If we are indeed seeing how critical digital connectivity is in times of crisis, should these networks, and our data, really be in the hands of private players like Google, Amazon, and Apple? If public funds are paying for so much of it, should the public also own and control it? If the internet is essential for so much in our lives, as it clearly is, should it be treated as a nonprofit public utility?

In each case, we face real and hard choices between investing in humans and investing in technology. Because the brutal truth is that, as it stands, we are very unlikely to do both. The refusal to transfer anything like the needed resources to states and cities in successive federal bailouts means that the coronavirus health crisis is now slamming headlong into a manufactured austerity crisis.

On the contrary: The price tag for all the shiny gadgets will be mass teacher layoffs and hospital closures.”

READ MORE https://theintercept.com/2020/05/08/andrew-cuomo-eric-schmidt-coronavirus-tech-shock-doctrine/

197 Comments “But it is in the area of 'regulatory capture' that Google has really excelled. Regulatory capture, according to Nobel laureate George Stigler, is the process by which regulatory agencies eventually come to be dominated by the very industries they were charged with regulating. Putting aside the fact that Google chairman Eric Schmidt has visited the Obama White House more than any other corporate executive in America and that Google chief lobbyist Katherine Oyama was associate counsel to Vice President Joe Biden, the list of highly-placed Googlers in the federal government is truly mind-boggling. . . .

"Google makes sure to place bets on both sides of the aisle. So while Eric Schmidt is advising Hillary Clinton's campaign, Larry Page flew with Sean Parker and Elon Musk in March of 2016 to a secret Republican meeting at a resort in Sea Island, Georgia, organized by the right-wing think tank the American Enterprise Institute. There they met with Republican leadership, including Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan as well as Karl Rove, to plan Republican 2016 election strategy. My own experience in talking to legislators about Internet reform has led me to understand that Google, Amazon, and Facebook are deeply embedded in both parties, and their interests will be protected no matter who is in the White House."

— Jonathan Taplin, Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy (2017)

0 notes

Text

Новости сайта #ENGINEERING - 工程

New Post has been published on http://engineer.city/making-total-qa-a-manufacturing-reality/

Making Total QA a manufacturing reality

In George Orwell’s 1984, he conceives a futuristic dystopia where Big Brother watches over every citizen. While his concept of constant surveillance of the population is an unwelcome thought, there are situations where an increased level of monitoring can lead to incredible benefits. Here Yonatan Hyatt, CTO of Inspekto, explores the concept of Total QA and the technology that has made it possible.

Total QA means performing quality assurance activity at every stage on the production line. While it sounds too good to be true, the development of Autonomous Machine Vision as an affordable, flexible and integrator-less technology means that Total QA is now a reality.

Out with the old

Traditionally, QA managers have only been able to install machine vision solutions at major junctions on the production line, because they are tailored, expensive and expert dependent. A traditional visual QA solution is custom built for a specific location as part of a complex project, which is orchestrated by the integrator. The manufacturer would rely on an external systems integrator for the entire lifespan of the project, as the skillset required makes the QA project completely inaccessible to the plant’s own staff.

Because installing inflexible, traditional solutions for one point on the production line is so time consuming and expensive, manufacturers have typically opted to benefit from machine vision only at major junctions. While this allows the business to identify defective products before they reach the customer, protecting their reputation, it does not allow manufacturers to protect themselves against unnecessary scrap. Total QA allows QA managers to remove a product from the production line as soon as it becomes defective, meaning that no additional time and cost is put into further production, only for it to be scrapped at the end of the line.

The inherent limitations of traditional machine vision also mean that the QA manager is held back from collecting the amount of data required for plant optimisation.

In with the new

The advent of Autonomous Machine Vision has opened the doors to Total QA. One reason for this is that the systems are available at one tenth of the cost of a traditional solution. Autonomous Machine Vision systems can also be installed by the plant’s own personnel in minutes, rather than over weeks or months.

Additionally, if the QA manager chooses to move the system to another location, it can quickly self-adapt — unlike an inflexible, traditional solution. The integrator-less deployment and reduction in cost means that manufacturers are no longer limited to visual QA only at major junctions. Rather, they can install visual QA at any point they feel necessary.

As well as finding the defects themselves, manufacturers can do root cause analysis to find out why they were introduced. A manufacturer operating using Total QA can trace through archived data to identify which equipment is the source of the problem and then take steps to correct it. By optimising the plant in this manner, the QA manager can prevent defects from being introduced in the future. If a manufacturer only has visual QA at major junctions, this is not possible. The manufacturer does not have the complete picture required to optimise their line and avoidable defects will continue to be introduced.

While surveillance of our day to day activities, like that of Big Brother in Orwell’s 1984, is something best kept in fiction, increased visual QA of our manufacturing lines is not. Enabled by Autonomous Machine Vision, Total QA is now a reality — allowing plants to reduce scrap, improve yield and optimise their lines.

Tags:

QA

Images:

Categories:

Process

Automation/Control

Source: engineerlive.com

0 notes

Text

Why tech CEOs are in love with doomsayers

Latest Updates - M. N. & Associates - By Nellie BowlesFuturist philosopher Yuval Noah Harari worries about a lot.He worries that Silicon Valley is undermining democracy and ushering in a dystopian hellscape in which voting is obsolete.He worries that by creating powerful influence machines to control billions of minds, the big tech companies are destroying the idea of a sovereign individual with free will.He worries that because the technological revolution’s work requires so few laborers, Silicon Valley is creating a tiny ruling class and a teeming, furious “useless class.”But lately, Harari is anxious about something much more personal. If this is his harrowing warning, then why do Silicon Valley CEOs love him so?“One possibility is that my message is not threatening to them, and so they embrace it?” a puzzled Harari said one afternoon in October. “For me, that’s more worrying. Maybe I’m missing something?”When Harari toured the Bay Area this fall to promote his latest book, the reception was incongruously joyful. Reed Hastings, chief executive of Netflix, threw him a dinner party. The leaders of X, Alphabet’s secretive research division, invited Harari over. Bill Gates reviewed the book (“Fascinating” and “such a stimulating writer”) in The New York Times.“I’m interested in how Silicon Valley can be so infatuated with Yuval, which they are — it’s insane he’s so popular, they’re all inviting him to campus — yet what Yuval is saying undermines the premise of the advertising- and engagement-based model of their products,” said Tristan Harris, Google’s former in-house design ethicist and a co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology.Part of the reason might be that Silicon Valley, at a certain level, is not optimistic on the future of democracy. The more of a mess Washington becomes, the more interested the tech world is in creating something else, and it might not look like elected representation. Rank-and-file coders have long been wary of regulation and curious about alternative forms of government. A separatist streak runs through the place: Venture capitalists periodically call for California to secede or shatter, or for the creation of corporate nation-states. And this summer, Mark Zuckerberg, who has recommended Harari to his book club, acknowledged a fixation with the autocrat Caesar Augustus. “Basically,” Zuckerberg told The New Yorker, “through a really harsh approach, he established 200 years of world peace.”Harari, thinking about all this, puts it this way: “Utopia and dystopia depends on your values.”Harari, who has a Ph.D. from Oxford, is a 42-year-old Israeli philosopher and a history professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The story of his current fame begins in 2011, when he published a book of notable ambition: to survey the whole of human existence. “Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind,” first released in Hebrew, did not break new ground in terms of historical research. Nor did its premise — that humans are animals and our dominance is an accident — seem a likely commercial hit. But the casual tone and smooth way Harari tied together knowledge across fields made it a deeply pleasing read, even as the tome ended on the notion that the process of human evolution might be over. Translated into English in 2014, the book went on to sell more than 8 million copies and made Harari a celebrity intellectual.He followed up with “Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow,” which outlined his vision of what comes after human evolution. In it, he describes Dataism, a new faith based around the power of algorithms. Harari’s future is one in which big data is worshipped, artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence, and some humans develop Godlike abilities.Now, he has written a book about the present and how it could lead to that future: “21 Lessons for the 21st Century.” It is meant to be read as a series of warnings. His recent TED Talk was called “Why fascism is so tempting — and how your data could power it.”His prophecies might have made him a Cassandra in Silicon Valley, or at the very least an unwelcome presence. Instead, he has had to reconcile himself to the locals’ strange delight. “If you make people start thinking far more deeply and seriously about these issues,” he told me, sounding weary, “some of the things they will think about might not be what you want them to think about.”‘Brave New World’ as Aspirational ReadingHarari agreed to let me tag along for a few days on his travels through the Valley, and one afternoon in September, I waited for him outside X’s offices, in Mountain View, while he spoke to the Alphabet employees inside. After a while, he emerged: a shy, thin, bespectacled man with a dusting of dark hair. Harari has a sort of owlish demeanor, in that he looks wise and also does not move his body very much, even while glancing to the side. His face is not particularly expressive, with the exception of one rogue eyebrow. When you catch his eye, there is a wary look — like he wants to know if you, too, understand exactly how bad the world is about to get.At the Alphabet talk, Harari had been accompanied by his publisher. They said the younger employees had expressed concern about whether their work was contributing to a less-free society, while the executives generally thought their impact was positive.Some workers had tried to predict how well humans would adapt to large technological change based on how they have responded to small shifts, like a new version of Gmail. Harari told them to think more starkly: If there isn’t a major policy intervention, most humans probably will not adapt at all.It made him sad, he told me, to see people build things that destroy their own societies, but he works every day to maintain an academic distance and remind himself that humans are just animals. “Part of it is really coming from seeing humans as apes, that this is how they behave,” he said, adding, “They’re chimpanzees. They’re sapiens. This is what they do.”He was slouching a little. Socializing exhausts him.As we boarded the black gull-wing Tesla Harari had rented for his visit, he brought up Aldous Huxley. Generations have been horrified by his novel “Brave New World,” which depicts a regime of emotion control and painless consumption. Readers who encounter the book today, Harari said, often think it sounds great. “Everything is so nice, and in that way it is an intellectually disturbing book because you’re really hard-pressed to explain what’s wrong with it,” he said. “And you do get today a vision coming out of some people in Silicon Valley which goes in that direction.”An Alphabet media relations manager later reached out to Harari’s team to tell him to tell me that the visit to X was not allowed to be part of this story. The request confused and then amused Harari. It is interesting, he said, that unlike politicians, tech companies do not need a free press, since they already control the means of message distribution.He said he had resigned himself to tech executives’ global reign, pointing out how much worse the politicians are. “I’ve met a number of these high-tech giants, and generally they’re good people,” he said. “They’re not Attila the Hun. In the lottery of human leaders, you could get far worse.”Some of his tech fans, he thinks, come to him out of anxiety. “Some may be very frightened of the impact of what they are doing,” Harari said.Still, their enthusiastic embrace of his work makes him uncomfortable. “It’s just a rule of thumb in history that if you are so much coddled by the elites it must mean that you don’t want to frighten them,” Harari said. “They can absorb you. You can become the intellectual entertainment.”Dinner, With a Side of Medically Engineered ImmortalityCEO testimonials to Harari’s acumen are indeed not hard to come by. “I’m drawn to Yuval for his clarity of thought,” Jack Dorsey, the head of Twitter and Square, wrote in an email, going on to praise a particular chapter on meditation.And Hastings wrote: “Yuval’s the anti-Silicon Valley persona — he doesn’t carry a phone and he spends a lot of time contemplating while off the grid. We see in him who we wish we were.” He added, “His thinking on AI and biotech in his new book pushes our understanding of the dramas to unfold.”At the dinner Hastings co-hosted, academics and industry leaders debated the dangers of data collection, and to what degree longevity therapies will extend the human life span. (Harari has written that the ruling class will vastly outlive the useless.) “That evening was small, but could be magnified to symbolize his impact in the heart of Silicon Valley,” said Fei-Fei Li, an artificial intelligence expert who pushed internally at Google to keep secret the company’s efforts to process military drone footage for the Pentagon. “His book has that ability to bring these people together at a table, and that is his contribution.”A few nights earlier, Harari spoke to a sold-out theater of 3,500 in San Francisco. One ticket-holder walking in, an older man, told me it was brave and honest for Harari to use the term “useless class.”The author was paired for discussion with the prolific intellectual Sam Harris, who strode onstage in a gray suit and well-starched white button-down. Harari was less at ease, in a loose suit that crumpled around him, his hands clasped in his lap as he sat deep in his chair. But as he spoke about meditation — Harari spends two hours each day and two months each year in silence — he became commanding. In a region where self-optimization is paramount and meditation is a competitive sport, Harari’s devotion confers hero status.He told the audience that free will is an illusion, and that human rights are just a story we tell ourselves. Political parties, he said, might not make sense anymore. He went on to argue that the liberal world order has relied on fictions like “the customer is always right” and “follow your heart,” and that these ideas no longer work in the age of artificial intelligence, when hearts can be manipulated at scale.Everyone in Silicon Valley is focused on building the future, Harari continued, while most of the world’s people are not even needed enough to be exploited. “Now you increasingly feel that there are all these elites that just don’t need me,” he said. “And it’s much worse to be irrelevant than to be exploited.”The useless class he describes is uniquely vulnerable. “If a century ago you mounted a revolution against exploitation, you knew that when bad comes to worse, they can’t shoot all of us because they need us,” he said, citing army service and factory work.Now it is becoming less clear why the ruling elite would not just kill the new useless class. “You’re totally expendable,” he told the audience.This, Harari told me later, is why Silicon Valley is so excited about the concept of universal basic income, or stipends paid to people regardless of whether they work. The message is: “We don’t need you. But we are nice, so we’ll take care of you.”On Sept. 14, he published an essay in The Guardian assailing another old trope — that “the voter knows best.”“If humans are hackable animals, and if our choices and opinions don’t reflect our free will, what should the point of politics be?” he wrote. “How do you live when you realize ... that your heart might be a government agent, that your amygdala might be working for Putin, and that the next thought that emerges in your mind might well be the result of some algorithm that knows you better than you know yourself? These are the most interesting questions humanity now faces.”‘OK, So Maybe Humankind Is Going to Disappear’Harari and his husband, Itzik Yahav, who is also his manager, rented a small house in Mountain View for their visit, and one morning I found them there making oatmeal. Harari observed that as his celebrity in Silicon Valley has risen, tech fans have focused on his lifestyle.“Silicon Valley was already kind of a hotbed for meditation and yoga and all these things,” he said. “And one of the things that made me kind of more popular and palatable is that I also have this bedrock.” He was wearing an old sweatshirt and denim track pants. His voice was quiet, but he gestured widely, waving his hands, hitting a jar of spatulas.Harari grew up in Kiryat Ata, near Haifa, and his father worked in the arms industry. His mother, who worked in office administration, now volunteers for her son handling his mail; he gets about 1,000 messages a week. Yahav’s mother is their accountant.Most days, Harari doesn’t use an alarm clock, and wakes up between 6:30 and 8:30 a.m., then meditates and has a cup of tea. He works until 4 or 5 p.m., then does another hour of meditation, followed by an hourlong walk, maybe a swim, and then TV with Yahav.The two met 16 years ago through the dating site Check Me Out. “We are not big believers in falling in love,” Harari said. “It was more a rational choice.”“We met each other and we thought, ‘OK, we’re — OK, let’s move in with each other,’ ” Yahav said.Yahav became Harari’s manager. During the period when English-language publishers were cool on the commercial viability of “Sapiens” — thinking it too serious for the average reader and not serious enough for the scholars — Yahav persisted, eventually landing the Jerusalem-based agent Deborah Harris. One day when Harari was away meditating, Yahav and Harris finally sold it at auction to Random House in London.Today, they have a team of eight based in Tel Aviv working on Harari’s projects. Director Ridley Scott and documentarian Asif Kapadia are adapting “Sapiens” into a TV show, and Harari is working on children’s books to reach a broader audience.Yahav used to meditate, but has recently stopped. “It was too hectic,” he said while folding laundry. “I couldn’t get this kind of huge success and a regular practice.” Harari remains dedicated.“If it were only up to him, he would be a monk in a cave, writing things and never getting his hair cut,” Yahav said, looking at his husband. “Can I tell that story?”Harari said no.“On our first meeting,” Yahav said, “he had cut his hair by himself. And it was a very bad job.”The couple are vegan, and Harari is particularly sensitive to animals. He identified the sweatshirt he was wearing as one he got just before one of his dogs died. Yahav cut in to ask if he could tell another story; Harari seemed to know exactly what he meant, and said absolutely not.“In the middle of the night,” Yahav said, “when there is a mosquito, he will catch him and take him out.”Being gay, Harari said, has helped his work — it set him apart to study culture more clearly because it made him question the dominant stories of his own conservative Jewish society. “If society got this thing wrong, who guarantees it didn’t get everything else wrong as well?” he said.“If I was a superhuman, my superpower would be detachment,” Harari added. “OK, so maybe humankind is going to disappear — OK, let’s just observe.”For fun, the couple watches TV. It is their primary hobby and topic of conversation, and Yahav said it was the only thing from which Harari is not detached.They just finished “Dear White People,” and they loved the Australian series “Please Like Me.” That night, they had plans to either meet Facebook executives at company headquarters or watch the YouTube show “Cobra Kai.”Harari left Silicon Valley the next weekend. Soon, in December, he will enter an ashram outside Mumbai, India, for another 60 days of silence. Chartered Accountant For consultng. Contact Us: http://bit.ly/bombay-ca

0 notes

Link