#beis hamikdash

Text

I mentioned this in the tags of an earlier post, but I wanted to explain a bit more about the alienated, shattered, exiled, othered imagery of the Divine in Judaism, and how that image of the Divine speaks deeply to me as a queer, non-binary Jew.

The Shechinah, the Divine Presence, is described in feminine terms and She goes with the Jewish people into galus, exile, at the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. What does it mean, for us to imagine G-d as being in exile with us? It's a profound image. We are exiled from our land, from the Beis HaMikdash and the closeness to the Divine Presence that it allowed, yes. But we are not totally cut off; the grief we feel is shared by Hashem Herself as we build a sacred remnant together in the diaspora. What does it mean, for the Divine Presence to be in exile with us, instead of whole? What do we learn from the idea that the sacred feminine is broken, exiled, and alienated along with the rest of klal Yisrael from the masculine Malchus? What does it say that the world will only be perfected (takken olam) when Hashem is One and Ha-Shem is One?

There is another image of the Divine that I've described here before, the holy darkness. The sacred dark that was before the beginning, that begins our days with ma'ariv, and that teaches us the lessons of infinity as the backdrop of the universe. To me it is a beautiful image, this idea that we are all sheltering under the wings of the Shechinah - that our darkness is the protective dark of an embrace. That we are held in a sukkat shalom - a shelter of peace. Like our sukkot, this does not mean we are safe or protected from the elements, but more that our home - our true home - is under the stars, and that no matter what, we are not alone. This article had a lot more fascinating things to say about this as well.

And finally, this image of a hidden G-d, a G-d that weeps for our suffering in G-d's hidden place (mistarim), who speaks silently, in the still small voice within our hearts. There's a drash that I'm still trying to track down about this because it was from several years ago, but it was about this hidden place of Hashem that G-d retreats to in order to grieve the sorrows of the world and how, if we truly want to be close to G-d, we will sit silently in that hidden place alongside Him.

These images and metaphors for G-d are not what is typically imagined. Most concepts of G-d are majestic in scope and elevated in stature. They are filled with the piercing bright light of clarity and gilded with the gold of the Mishkan, the First Temple, and the Second Temple. But we live in a humbler time. Hashem is Avinu Malkeinu - our compassionate, forgiving Father and the Ruler of the Universe, but what does that divine concept do for us when we live in a broken and unredeemed world? How can that traditional understanding of G-d speak to us when we are calling out to G-d from the depths? And especially for those of us who are seen as broken, dwelling in darkness, often hiding our true selves, and exiled from where we belong, how much more powerful is an understanding of G-d that goes into that exile with us and holds us in our grief and hard-won joy, as we endure together?

504 notes

·

View notes

Text

How does my MIL always manage to find the WEIRDEST “Jewish” books to give my kids though.

In this batch:

“The Story of Hanukkah,” in which the point of the Beis HaMikdash was apparently a “ner tamid,” which was the thing whose oil lasted for 8 days, but then inexplicably after that people started lighting a 7-branched menorah on the 25th of Kislev from then on? Also multiple people are portrayed standing inside what appears to be the Kodesh HaKedoshim with one of said menorahs inside it. Then the next page it’s an actual Chanukah menorah but we are told it’s lit to remember the ner tamid. Oh also, apparently before the Chanukah story, everyone just walked right into the Kodesh HaKedoshim every holiday.

“The Night Before Hanukkah,” part of a series that also includes such Jewish favorites by the same author as “The Night Before Easter” and “The Night Before My First Communion,” written in a style paying homage to the thing you think it does. Full of illustrations of dreidels with totally wrong letters, blue and white Xmas - sorry, Chanukah - decorations, hands clasped in prayer, and candles placed in the wrong order.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A freilichen Chanuka! Chanuka Sameach!

May we soon merit to light the menorah in the Beis Hamikdash.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this night 2,186 years ago, the victorious Makabim entered the Beys HaMikdash to light the seven lamps of the holy menorah, but the pure gold menorah had been stolen during the occupation by the Greco-Assyrians. Instead, they used seven spears left by their fleeing enemies to fashion a lampstand, and lit the holy lights on it. The weapons meant for their destruction then shone with the light of the indestructible Jewish Spirit for the eight day re-dedication (chanukah) of the Temple.

What was meant to destroy us, only made us shine. And two thousand years later, despite subsequent invasion, exile, and many more attempted genocides, that light still shines as brightly as it did when it shone from a menorah made of spears. This is Chanukah.

#chanukah#Makkabees#Judah Maccabee#Maccabees#Chanukah miracle#Jewish#Jewish history#jewish culture#jew#jew stuff#jewish#jewish history#jewish holidays

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

do jews use incense?

Incense (aromatic biotics burnt for specific aromas) has played a part in Judaism since before the time of the Temple.

A specific kind of fragrant incense, ketoret, burned at the altar within the Temple twice daily as an offering. It “was created of 11 fragrant herbs, identified by Maimonides as, "Onycha, Storax, Frankincense, Musk, Cassia, Spikenard, Saffron, Costus, Cinnamon, Agarwood," with the addition of "salt of Sodom and Jordanian amber. Another two ingredients (vetch lye and "caper wine") were used in preparation of the tziporen (onycha) spice. There was also a special herb, referred to simply as maaleh ashan ("makes smoke rise"), that would produce a pillar of smoke that rose straight up rather than spread out. The identity of the herb was a secret that was closely guarded by members of the Avitnus family, who made the incense based on the tradition of their ancestor" (13). Read more here.

However, since the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash, the creation and burning of ketoret was rendered impossible, and thus official 'incense' in the mind of many Jews was forced out.

Burning specific herbs for specific reasons, including their fragrant scent, however, has continued in many Jewish communities, often coexisting and intermingling with 'official' practices. This incense (distinct from the ketoret incense of the Beis Hamikdash) takes on many different recipes and forms; including modern incense.

These practices vary by community and group and in the modern era, many Jews accept that incense, much like modern scented candles, are not offerings to other deities, but rather a means of beautifying and adorning our spaces. So, yes, many Jews use incense, and other Jews do not.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

beis hamikdash longing hours

(aka tikkun chatzos)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jerusalem Temple Paintings A Glimpse into Holy Legacy

Jerusalem Temple paintings offer a glimpse into the sacred precincts that have shaped religious and cultural history. Artists capture the Temple's intricate details and spiritual ambiance, invoking a sense of reverence and wonder. Each painting becomes a visual meditation, inviting viewers to reflect on the Temple's enduring impact and significance. Through Jerusalem Temple paintings, the legacy of the sacred site is preserved, ensuring its stories continue to inspire.

0 notes

Text

A Casa Museu Ema Klabin recebe, no dia 10 de setembro, às 16h30, o espetáculo de abertura do 13º Kleztival 2022. O show Khazntes, vozes femininas na liturgia judaica contará com a participação das cantoras Nicole Borger, Regis Karlik, Roxana Kostka e o Trio In Canto – formado por Lea Gabanyi, Sonia Oppenheim e Vanessa Nunes –, além de José Langer, no violão, e Sima Halpern, no piano e na direção musical.

Nas décadas de 1930 a 1950, em Nova York, havia um grupo de mulheres, esposas, filhas, irmãs, sobrinhas de cantores litúrgicos famosos, que, impedidas de cantar em sinagogas, lotavam teatros cantando repertórios de canções litúrgicas para um amplo público. Perele Feig, Freydele Oysher, Sarah Gorby, Bas Sheva, Sophie Kurtzer, Sheindele Khaznte e Goldie Makawski, mulheres que contribuíram para a divulgação da cultura judaica, serão homenageadas na apresentação.

No programa: Shehecheianu, Tehilim, Shma Koleinu, Nigun Hassidi, Dudele, Haleluia, haleluhu, Kevakoras, Shma Israel, Kol Nidre, HaBen Yakir Li, Avinu Malkeinu, Sheyibone Beis Hamikdash.

Principal Festival de Música Judaica:

O 13º Kleztival, edição Bar Mitzvah, acontece de 10 a 18 de setembro. O evento é promovido pelo IMJ Brasil, uma organização sem fins lucrativos dedicada à divulgação da música judaica no Brasil. A programação completa do Festival pode ser conferida em: http://www.imjbrasil.com.br/kleztival.html

Serviço:

Abertura do 13º Kleztival 2022

Khazntes, vozes femininas na liturgia judaica

10 de setembro, às 16h30

60 lugares presenciais por ordem de chegada

Gratuito*

Rua Portugal, 43, Jardim Europa, SP

Acesse nossas redes sociais:

Instagram: @emaklabin

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/fundacaoemaklabin

Twitter: https://twitter.com/emaklabin

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC9FBIZFjSOlRviuz_Dy1i2w

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/emaklabin/?original

*Como em todos os nossos eventos gratuitos, convidamos quem aprecia a Casa Museu Ema Klabin e pode contribuir para a manutenção das nossas atividades a nos apoiar com uma doação voluntária via pix: 51204196000177

*Todos os artigos publicados são de responsabilidade exclusiva de seus autores e não expressam a linha editorial do portal e de seus editores.

0 notes

Note

So in service to God, you bless his creation ,the Moon, once a month, because at that specific time it determines the start of each month. The start of each month is important because .... it is a measurement of time... which is connected to womanhood?

The start of each month is important because

a) Hashem said so, and

b) the first day of the month determines when all the other days of the month will fall.

This second reason may seem overly obvious if you aren't familiar with how the Jewish calendar is actually supposed to work, which is not in fact how it works now. Now, because we're in galus, we have a fixed calendar. I can look up when Pesach will fall decades and decades from now if I want. But back in the day, we didn't have a fixed calendar. Any month could be either 29 or 30 days, and which it would be was determined by witnesses sighting the new moon and reporting to the Sanhedrin in Yerushalayim. So you wouldn't know exactly which day was going to be Pesach until Rosh Chodesh Nissan was declared. The halachic procedure for declaring Rosh Chodesh is therefore incredibly significant and holy because it literally determines which other days of the year will be holidays vs. not. When melacha will be allowed vs. not, when holiday-specific prayers will be said instead of the weekday ones, when (in the times of the Beis HaMikdash) the sacrifices associated with each holiday would be brought rather than merely the typical weekday ones. Although we are unfortunately unable to operate this way under the current circumstances, that doesn't take away from the ultimate significance of Rosh Chodesh.

And yes, there is an association between women and Rosh Chodesh, but that's not *why* Rosh Chodesh is important.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Av

[vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” column_margin=”default” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” color_overlay=”#ffffff” overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” bg_image_animation=”none” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

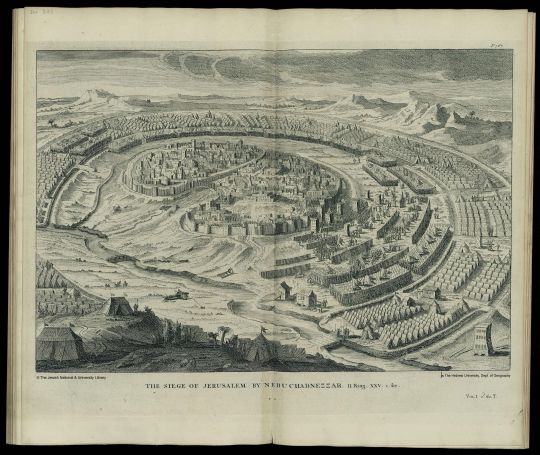

233 years after the Maccabees freed their homeland of oppressive colonisers, Israel was once again invaded and colonised - this time by Rome. Unfortunately this part of the story doesn’t have a happy ending. In the year 69 CE the Romans would burn the Beys HaMikdash and forcibly expel the Jews from Israel, beginning nearly 2,000 years of exile for the Jewish people. This Roman victory was immortalizes on the Arch of Titus - which depicts the plunder of the Temple. Most notably, it shows the Romans carrying off the golden menorah rebuilt by the Hasmoneans. The arch faces in towards Rome to show the victors carrying their spoils from Jerusalem to Rome, and the Jews of Rome had always had the custom that they would never walk under the arch depicting the greatest tragedy in Jewish history.

But, the story does ultimately have a happy ending - about two thousand years later the descendants of those Jews who instituted the custom to never walk under the Arch of Titus gathered to do just that. On 5 Iyar 5708 / 14 May 1948 the Jewish community of Rome gathered at the arch of Titus to walk through it for the first time - backwards - toward Jerusalem, away from Rome. After 2,000 years the exile was ending. And when the newly re-born country of Israel needed a symbol, the very image of the menorah from the Arch of Titus was what was chosen. An image meant to show our downfall is now a symbol of the greatest victory for the Jewish community since the Maccabees. This is Chanukah.

#chanukah#arch of titus#maccabean revolt#the maccabees#Maccabees#israel#jew#jew stuff#jewish#jewish culture#jewish history#jewish holidays

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

It took me this long to notice how ironic the line "one destroyed temple does not erase thousands of years of tradition!" in Prince of Egypt is.

11 notes

·

View notes