#based upon the story by lillian hellman

Photo

You only heard the statement of the loss. You did not see the father fall as Pilar made him see the fascists die in that story she had told by the stream. You knew the father died in some courtyard, or against some wall, or in some field or orchard, or at night, in the lights of a truck, beside some road. You had seen the lights of the car from down the hills and heard the shooting and afterwards you had come down to the road and found the bodies. You did not see the mother shot, nor the sister, nor the brother. You heard about it; you heard the shots; and you saw the bodies.

- Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls

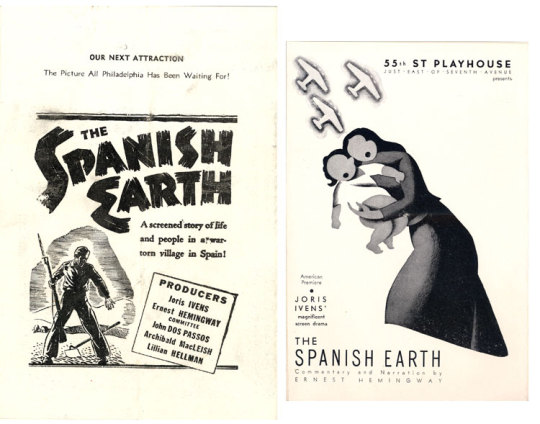

The 1937 film The Spanish Earth, was an important visual document of the Spanish Civil War and a rare record of the famous writer's voice. Hemingway went to Spain in the spring of 1937 to report on the war for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA), but spent a good deal of time working on the film.

Before leaving America, he and a group of artists that included Archibald MacLeish, John Dos Passos and Lillian Hellman banded together to form Contemporary Historians, Inc., to produce a film to raise awareness and money for the Spanish Republican cause. The group came up with $18,000 in production money - $5,000 of it from Hemingway - and hired the Dutch documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, a passionate leftist, to make the movie.

MacLeish and Ivens drafted a short outline for the story, with a theme of agrarian reform. It was MacLeish who came up with the title. The film, as they envisioned it, would tell the story of Spain's revolutionary struggle through the experience of a single village. To do that, Ivens planned to stage a number of scenes. When he and cameraman John Fernhout (known as "Ferno") arrived in Spain they decided to focus on the tiny hamlet of Fuentedueña de Tajo, southeast of Madrid, but they soon realised it would be impossible to set up elaborate historical re-enactments in a country at war. They kept the theme of agrarian struggle as a counterpoint to the war.

When Dos Passos arrived in Fuentedueña, he encouraged that approach. "Our Dutch director," wrote Dos Passos, "did agree with me that, instead of making the film purely a blood and guts picture we ought to find something being built for the future amid all the misery and massacre."

That changed when Hemingway arrived.

The friendship between the two writers was disintegrating at the time, so they didn't work together on the project. It was agreed upon in advance that Hemingway would write the commentary for the film, but while in Spain he also helped Ivens and Fernhout navigate the dangers of the war zone. Hemingway was a great help to the film crew. With a flask of whisky and raw onions in his pockets, he lugged equipment and arranged transport. Ivens generally wore battle dress and a black beret. Hemingway went as far as a beret but otherwise stuck to civvies. Although he rarely wore glasses, he almost never took them off in Spain, clear evidence of the seriousness of their task."

In Night Before Battle, a short story based partially on his experience making the movie, Hemingway describes what it's like filming in a place where the glint from your camera lens draws fire from enemy snipers:

“At this time we were working in a shell-smashed house that overlooked the Casa del Campo in Madrid. Below us a battle was being fought. You could see it spread out below you and over the hills, could smell it, could taste the dust of it, and the noise of it was one great slithering sheet of rifle and automatic rifle fire rising and dropping, and in it came the crack of the guns and the bubbly rumbling of the outgoing shells fired from the batteries behind us, the thud of their bursts, and then the rolling yellow clouds of dust. But it was just too far to film well. We had tried working closer but they kept sniping at the camera and you could not work.”

The big camera was the most expensive thing we had and if it was smashed we were through. We were making the film on almost nothing and all the money was in the cans of film and the cameras. We could not afford to waste film and you had to be awfully careful of the cameras.

The day before we had been sniped out of a good place to film from and I had to crawl back holding the small camera to my belly, trying to keep my head lower than my shoulders, hitching along on my elbows, the bullets whocking into the brick wall over my back and twice spurting dirt over me.

The Western front at Casa de Campo on the outskirts of Madrid was just a few minutes' walk from the Florida Hotel, where the filmmakers were staying. Any doubt about whether the passage from "Night Before Battle" is autobiographical are dispelled in the following excerpt from one of Hemingway's NANA dispatches, quoted by Schoots:

“Just as we were congratulating ourselves on having such a splendid observation post and the non-existent danger, a bullet smacked against a corner of brick wall beside Ivens's head. Thinking it was a stray, we moved over a little and, as I watched the action with glasses, shading them carefully, another came by my head. We changed our position to a spot where it was not so good observing and were shot at twice more. Joris thought Ferno had left his camera at our first post, and as I went back for it a bullet whacked into the wall above. I crawled back on my hands and knees, and another bullet came by as I crossed the exposed corner. We decided to set up the big telephoto camera. Ferno had gone back to find a healthier situation and chose the third floor of a ruined house where, in the shade of a balcony and with the camera camouflaged with old clothes we found in the house, we worked all afternoon and watched the battle.”

In May, Ivens returned to New York to oversee the work of editor Helen van Dongen. Hemingway soon followed. When Ivens asked Hemingway to clarify the theme of the picture, according to Kenneth Lynn in his erudite biography Hemingway (1987), the writer supplied three sentences: "We gained the right to cultivate our land by democratic elections. Now the military cliques and absentee landlords attack to take our land from us again. But we fight for the right to irrigate and cultivate this Spanish Earth which the nobles kept idle for their own amusement."

There were tense moments when Hemingway handed in his first draft of the commentary. Ivens felt it was too verbose, and asked him to make some cuts. Hemingway didn't like being told to shorten his work, but he eventually agreed. There was more tension when MacLeish asked Orson Welles to deliver the narration. Even though Hemingway had already shortened it, Welles thought the commentary was too long, and he told him so.

"Arriving at the studio," Welles said in a 1964 interview with Cahiers du Cinema, "I came upon Hemingway, who was in the process of drinking a bottle of whiskey; I had been handed a set of lines that were too long, dull, had nothing to do with his style, which is always so concise and so economical. There were lines as pompous and complicated as this: 'Here are the faces of men who are close to death,' and this was to be read at a moment when one saw faces on the screen that were so much more eloquent. I said to him, 'Mr. Hemingway, it would be better if one saw the faces all alone, without commentary.'"

Hemingway growled at him in the dark studio, according to Welles, and said, "You effeminate boys of the theatre, what do you know about real war?" Welles continues the story:

“Well, taking the bull by the horns, I began to make effeminate gestures and I said to him, "Mister Hemingway, how strong you are and how big you are!" That enraged him and he picked up a chair; I picked up another and, right there, in front of the images of the Spanish Civil War, as they marched across the screen, we had a terrible scuffle. It was something marvelous: two guys like us in front of these images representing people in the act of struggling and dying...We ended up toasting each other over a bottle of whisky.”

Skeptics have questioned the truthfulness of Welles's account, suggesting that he may have been trying to compensate for his own moment of humiliation, which followed soon after the recording session. MacLeish and Ivens liked Welles's performance, but Hellman and several other members of the Contemporary Historians group didn't. They thought Welles had been too theatrical, and suggested Hemingway read the narration himself.

The director eventually agreed. "When Ivens informed Welles that his own recording was going to be junked," writes Lynn, "Welles was miffed, especially since he had waived his right to a fee."

On July 8, 1937, Ivens, Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, a journalist who had been with Hemingway in Spain and who would later become his wife, traveled to the White House to show the film to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The visit had been arranged by Gellhorn, who was a friend of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

A few days later Hemingway and Ivens traveled to Los Angeles to show the film to Hollywood moguls and movie stars. F. Scott Fitzgerald attended the screening, and the party afterward. It was the last time Hemingway and Fitzgerald saw each other. When Hemingway was back on the East Coast, Fitzgerald sent him a telegram: "THE PICTURE WAS BEYOND PRAISE AND SO WAS YOUR ATTITUDE."

The press reviews for The Spanish Earth tended to be a bit more equivocal. Some felt the film descended into out-and-out propaganda, to which Ivens later replied, "on issues of life and death, democracy or fascism, the true artist cannot be objective." But the writer of a 1938 article in Time magazine saw the film in a positive light:

“Not since the silent French film, The Passion of Joan of Arc, has such dramatic use been made of the human face. As face after face looks out from the screen the picture becomes a sort of portfolio of portraits of the human soul in the presence of disaster and distress. There are the earnest faces of speakers at meetings and in the village talking war, exhorting the defense. There are faces of old women moving from their homes in Madrid for safety's sake, staring at a bleak, uncertain future, faces in terror after a bombing, faces of men going into battle and the faces of men who will never return from battle, faces full of grief and determination and fear.”

In the end, with its mix of documentary and re-constructed elements, The Spanish Earth is at once a less elaborate but more complex film than that first conceived by Ivens. One critic aptly describes it as "an improvised hybrid of many filmic modes." This gives the film a curiously contemporary feel, but what really marks it out as a landmark of documentary filmmaking is its directness, its sense of immediacy, and its refusal to have any truck with spurious notions of "objectivity."

Ivens himself states that "My unit had really become part of the fighting forces," and again, "We never forgot that we were in a hurry. Our job was not to make the best of all films, but to make a good film for exhibition in the United States, in order to collect money to send ambulances to Spain. When we started shooting we didn't always wait for the best conditions to get the best shot. We just tried to get good, useful shots."

When asked why he hadn't tried to be more "objective" Ivens retorted that "a documentary film maker has to have an opinion on such vital issues as fascism or anti-fascism - he has to have feelings about these issues, if his work is to have any dramatic, emotional or art value," adding that "after informing and moving audiences, a militant documentary film should agitate - mobilise them to become active in connection with the problems shown in the film." Ivens would later justify his beliefs by stating, "on issues of life and death, democracy or fascism, the true artist cannot be objective."

Not that The Spanish Earth is in any sense strident - indeed, quite the reverse. Ivens understood fully the power of restraint and suggestion, quoting approvingly, à propos his film, John Steinbeck's observation of the London blitz that "In all of the little stories it is the ordinary, the commonplace thing or incident against the background of the bombing that leaves the indelible picture."

Ivens's visual restraint is matched by that of the commentary. The original commentary by Orson Welles did feel out of place and I would agree with Ivens sentiment that, "There was something in the quality of Welles’ voice that separated it from the film, from Spain, from the actuality of the film." Hemingway's manner of speaking, however, perfectly matched the pared-down quality of his writing. Ivens saw the function of the commentary as being "to provide sharp little guiding arrows to the key points of the film" and as serving as "a base on which the spectator was stimulated to form his own conclusions." He described Hemingway's mode of delivery as sounding like that of "a sensitive reporter who has been on the spot and wants to tell you about it. The lack of a professional commentator's smoothness helped you to believe intensely in the experiences on the screen."

Overall the film's avoidance of overt propagandising reflected not only Ivens' conception of the documentary aesthetic - it was also hoped that this might help The Spanish Earth achieve a wide theatrical release. However, as in Britain, there was thought to be no cinema audience for documentary films, and the plan failed. Nor did it help the film to escape the watchful eye of the British Board of Film Censors (who had previously attacked Ivens' New Earth) , who insisted that all references to Italian and German intervention were cut from the commentary, those countries being regarded as "friendly powers" at the time.

Photo (above): Ernest Hemingway and director Joris Ivens During the shooting of "The Spanish Earth" (1937).

#hemingway#ernest hemingway#the spanish civil war#war#the spanish earth#documentary#joris ivens#ivens#film#movie#cinema#orson welles#welles#f scott fitzgerald#europe#propaganda#art#aesthetics#film director#america#spain#fascism#franco

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

363. Júlia (Julia, 1977), dir. Fred Zinnemann

#cinema#fred zinnemann#jane fonda#vanessa redgrave#american movies#1970s movies#classic movies#technicolor#drama#based upon the story by lillian hellman#based on true story#nazi germany#lillian hellman character#1930s#romantic friendship#berlin germany#female bonding#railway station#border#flashback#typewriter#cinematography by douglas slocombe#film editing by walter murch#academy awards winner#bafta awards winner#césar awards nominee#dga awards nominee#cult director#cinefilos

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The case of Miss Woods and Miss Pirie against Lady Helen Cumming Gordon may be somewhat familiar to contemporary readers because it provides the source material for The Children’s Hour, first written and produced in 1934 by Lillian Hellman. The play itself was controversial when it was staged, though the word “lesbian” was never uttered and Hellman herself denied that the play was about lesbians at all. Then what was it about? Lying apparently, and the terrible damage that a stray rumor adapted from a lie can do. In 1934, the Hays Code had made it illegal to even mention homosexuality in films, but this censorship did not extend to Broadway plays. So, though the material on lesbianism could be more directly addressed in the play, it had to be buried when the play was made into a film. Director William Wyler made two different film adaptations of the play. In the 1936 adaptation, he based the film on the play but transformed the female drama into a heterosexual love triangle. He also changed the name of the production to These Three to avoid any connection to the scandalous material in the play. But when Wyler made the play into a film again in 1961 following the lifting of the Hays Code, lesbianism emerged from the shadows and became the clear (but still unspeakable) accusation directed at two teachers by a malicious pupil. Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine bring the characters to life in much acclaimed performances. On account of the dramatic tension that the two women generate, the complexities of the friendship that they negotiate, and despite the depressing ending, the film became a classic of gay and lesbian cinema.

Lillian Faderman first encountered the source material through Hellman’s drama when she played the role of the malicious pupil, Mary Tilford, in a school production. Later, as a professor, she returned to the case material that informed the play and decided to learn more about the mysterious Scottish case upon which the play about rumors, lies, and sexual intrigue between women was based. [...] In this midst of this contest between legal understandings of sex, social definitions of friendship and contemporary readings of historical material, there is another very important aspect of this case that stands out to a current reader as a marker of shifting views of identity. The girl who brings the accusations against the schoolteachers in the original nineteenth-century case was an Anglo-Indian child. Jane Cumming, as Faderman explains, was the daughter of George Cumming and a very young Indian woman (she was fifteen years old when she gave birth to Jane, according to Faderman’s account). George Cumming was Lady Cumming Gordon’s eldest son and, like so many other young British men of that time, he went to India in the employ of the British East India Company. Once in India, again like so many others, he had access to young Indian women. Soon after the birth of his daughter, he succumbed to disease and died at the age of twenty-seven. His daughter was then brought to Scotland to live with her grandmother and subsequently placed in Miss Pirie’s and Miss Woods’ School for Young Ladies.

The fact that Jane Cumming was Anglo-Indian gave the original case much of its ambiguity. In her stage version, Hellman left out this part of the case, making Mary Tilford a white, unpleasant bully. Her play pivots upon the maliciousness of the child. In the original court case, however, much was made of the possibility that Jane Cumming had been exposed to licentious behavior in India that was unthinkable in Scotland. One judge, for example, remarks: “However well known the crime charged here may be amongst Eastern nations, this is the first instance on record of such an accusation having been made in this country” (239). Another, Lord Meadowbank, refers the courtroom to “two Hindoo laws” in order to propose that while this kind of behavior might be commonplace in India, “the imputed vice has been hitherto unknown in Britain” (259).

Charging the foreign Jane Cumming with fabricating the whole story based upon her early exposure to “vice” allows all concerned to rest assured that whatever depravity might occur “over there,” British women remained cloistered from such knowledge and were beyond any suspicion of dubious sexual conduct. Faderman herself, writing in 1982, succumbs to some of the orientalism that taints the original texts. Describing Jane Cumming early on as probably “very much Indian, of the large type rather than the delicate, with heavy eyelids,” Faderman sometimes unconsciously echoes the sentiments of the judges, Lord Meadowbank in particular. He even who remarks at one point: “I detect something inscrutable and disturbing about this child of India” (189)!” As suspicious as she herself may have been of Jane Cumming’s testimony, Faderman still conveys the injustice done to Cumming by the judges and lawyers. She also knows that the lawyer for Woods and Pirie bases his case upon the idea that “Jane Cumming is not a reliable witness because she is illegitimate, a native of India, and colored” (222).

—Judith Halberstam, foreword to Lillian Faderman’s Scotch Verdict: The Real-Life Story That Inspired The Children’s Hour.

#judith halberstam#lillian faderman#the children's hour#history#jane cumming#marianne woods#jane pirie#india#scotland

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

We Asked 15 Wine Pros: Which Bordeaux Offers the Best Bang for Your Buck?

As one of the world’s premier wine regions, Bordeaux’s main focus is Cabernet Sauvignon- and Merlot-driven blends. While Cabernet Franc, Malbec, and Petit Verdot make regular appearances, the region is also known for producing small amounts of white Bordeaux, as well as the lusciously sweet wine known as Sauternes.

Bordeaux is divided into three regions — the rival Left Bank and Right Bank, and Entre-Deux-Mers — each with its own distinct terroir. As a result, deciphering Bordeaux’s many variations can be tricky. Add Bordeaux’s often intimidating prices, and it’s not hard to understand why oenophiles on a budget often shy away from its wines. However, a great bottle of Bordeaux doesn’t have to break the bank.

To ensure that approachable Bordeaux is on the radar for every drinker, VinePair asked wine professionals around the country which bottles of Bordeaux present the very best value.

As bars and restaurants continue to navigate the coronavirus pandemic and reopening phases, VinePair asked the bartenders and drinks professionals below to provide a virtual tip jar or fund of their choice. More resources for helping hospitality professionals are available here.

“Château d’Armailhac, Pauillac, Bordeaux, France 2016. One of the great values, especially when great older vintages can be found. An elegant Bordeaux with the technical expertise of the team behind Château Mouton Rothschild.” — Jhonel Faelnar, Wine Director, Atomix, NYC

“I think the wines of Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste have been getting increasingly better without huge jumps in the price for some time.” — Rusty Rastello, Wine Director, SingleThread, Healdsburg, Calif.

Donate: NAACP; The United Sommeliers Foundation

“This is an easy one… if you are looking for well-known, high-end Bordeaux — best bang I’d suggest [is] Brane Cantenac. If you want lesser-known Bordeaux at a more accessible price point, Chateau Biac or Haut Bailly.” — Carrie Lyn Strong, Wine Director/Sommelier, Casa Lever, NYC

Donate: Carrie Lyn Strong Venmo

“If you are a fan of Bordeaux, I recommend looking to Southwest France for value wines. Buzet, a small appellation known for its Merlot and Cabernet blends, offers really great wine for a fraction of the cost that you would pay for great Bordeaux. [The] 2016 Mary Taylor Wines Buzet punches above its weight. You get those wonderful aromas of tobacco, black fruit, and leather that invoke Right Bank comparisons. It retails around $18.” — Etinosa Emokpae, Wine Director, Friday Saturday Sunday, Philadelphia

“Château Beauséjour ‘Pentimento,’ Montagne-Saint-Émilion. This wine tells a story. It’s made by the first American female making wine in Bordeaux. I had the pleasure of working with the winemaker, Michelle D’ Aprix, at Bin 14 wine bar when she was traveling to France several times in the year to produce her first vintage. It is named Pentimento after one of her favorite books, “Pentimento,” by playwright Lillian Hellman. Just like the memoir muses on the people and experiences that have had a profound influence on her life, Michelle felt the same with her first wine label. The wine is farmed and made using little to no intervention for each vintage. [It’s] a wine that can be enjoyed upon release — no aging required — while pleasing Old World and New World palates alike.” — Madeline Maldonado, Beverage Director, da Toscano, NYC

“Château Haut-Segottes Saint Emilion Grand Cru (Cabernet Franc, Merlot). [Chateau Haut-Segottes is] owned and operated by Danielle Meunier. Smoked cherries, cigar, and peppercorn make it feel distinctly Bordeaux. Great with rich and rustic food but still light enough for other cuisines.” — Emmanuelle Massicot, Assistant General Manager, Kata Robata, Houston

“White Bordeaux. Probably not what you were expecting, I know. But if you haven’t spent time drinking the white blends of Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, and Muscadelle from Bordeaux, you’re missing out. Graville-Lacoste Graves Blanc is a delicious blend of mostly Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc, with just a touch of Muscadelle.” — Theo Lieberman, Beverage Director, 232 Bleecker, NYC

Donate: 232 Bleecker Gift Cards

“This is a little tricky because the casual wine drinker tends to equate Bordeaux with unrivaled decadence and sophistication, which isn’t entirely untrue, but it’s certainly not the case across the board. The Cabernet-driven wines of Margaux aren’t the cheapest, but they’re consistent in texture, intensity, and quality.” — Kyle Pate, Sommelier, Tinker Street, Indianapolis

“2019 Château Le Bergey, Bordeaux, France ($12). Biodynamic and Bordeaux aren’t two words you often hear in the same sentence, unless you’re talking about this wine. It has everything you could want from a classic Cabernet-dominant blend and tastes like it should cost three times the amount — but doesn’t, which is great.” — Luke Sullivan, Head Sommelier, Gran Tivoli & Peppi’s Cellar, NYC

“Château Larruau, Margaux 2015 is an elegant and sophisticated Bordeaux that offers exceptional value. [The] estate is located next to Chateau Margaux, but the Larruau is a fraction of the price.” — Marsella Charron, Sommelier, The Harbor House Inn, Elk, Calif.

Donate: Alder Springs Vineyard “A Case for a Cause”

“Château La Garde from Pessac-Léognan in Bordeaux. Roughly equal parts Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, this wine explodes from the glass with violet, blackberry, and smoky notes. It’s structured and full with great minerality and firm tannins. Retails around $25.” — Matthew Pridgen, Wine Director, Underbelly Hospitality, Houston

“For value Bordeaux, I often go to the Côtes, but customers in the restaurant are often more familiar with Medoc, so I generally steer people to Château Castera. I’m fascinated by its history, dating from the Middle Ages, and I think being Merlot-predominant, it’s much more versatile [than] many Cab-based Bordeaux wines for pairing with multiple dishes. I generally can find this wine with a few more years on it than the current release of other wines, which customers appreciate.” — Jeff Harding, Wine Director, Waverly Inn & Garden, NYC

Donate: Jeff Harding Venmo

“Clos du Jaugueyron (any bottling). Bordeaux is big business. Dealing in large quantities can lead houses to make choices that sacrifice long-term vineyard health for short-term financial assurance. However, there are some winemakers who are doing things in a more old-school way, focusing on sustainability and rejecting chemical use — perhaps none better than winemaker Michel Théron of Clos du Jaugueyron. His entry level Haut-Medoc can be found for under $50 most places, while his top-of-the-line Margaux bottling will run you just shy of $100.” — Andrew Pattison, Beverage Director, Sushi Note, Los Angeles

“Château Biac is located in Cadillac, in the Entre-Deux-Mers. When the Asseily family acquired and revived the estate in 2006, the vineyards were rethought and now have dedicated old-vine blocks for Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Cabernet Franc. The wines are full-bodied and juicy! The structure and complexity definitely rival the growths of the Left Bank. For more bang for the buck, go for the Felix de Biac, the little sister to the flagship.” — Stefanie Schwartz, Sommelier, Portale, NYC

Donate: Stefanie Schwartz Venmo

“Best Bordeaux for the price — Château Potensac or Château Ormes de Pez.” — Zac Adcox, Advanced Somm, indo, St. Louis

Donate: The United Sommeliers Foundation

The article We Asked 15 Wine Pros: Which Bordeaux Offers the Best Bang for Your Buck? appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/15-best-quality-bordeaux-brands-price/

source https://vinology1.tumblr.com/post/627523703115317248

0 notes

Text

We Asked 15 Wine Pros: Which Bordeaux Offers the Best Bang for Your Buck?

As one of the world’s premier wine regions, Bordeaux’s main focus is Cabernet Sauvignon- and Merlot-driven blends. While Cabernet Franc, Malbec, and Petit Verdot make regular appearances, the region is also known for producing small amounts of white Bordeaux, as well as the lusciously sweet wine known as Sauternes.

Bordeaux is divided into three regions — the rival Left Bank and Right Bank, and Entre-Deux-Mers — each with its own distinct terroir. As a result, deciphering Bordeaux’s many variations can be tricky. Add Bordeaux’s often intimidating prices, and it’s not hard to understand why oenophiles on a budget often shy away from its wines. However, a great bottle of Bordeaux doesn’t have to break the bank.

To ensure that approachable Bordeaux is on the radar for every drinker, VinePair asked wine professionals around the country which bottles of Bordeaux present the very best value.

As bars and restaurants continue to navigate the coronavirus pandemic and reopening phases, VinePair asked the bartenders and drinks professionals below to provide a virtual tip jar or fund of their choice. More resources for helping hospitality professionals are available here.

“Château d’Armailhac, Pauillac, Bordeaux, France 2016. One of the great values, especially when great older vintages can be found. An elegant Bordeaux with the technical expertise of the team behind Château Mouton Rothschild.” — Jhonel Faelnar, Wine Director, Atomix, NYC

“I think the wines of Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste have been getting increasingly better without huge jumps in the price for some time.” — Rusty Rastello, Wine Director, SingleThread, Healdsburg, Calif.

Donate: NAACP; The United Sommeliers Foundation

“This is an easy one… if you are looking for well-known, high-end Bordeaux — best bang I’d suggest [is] Brane Cantenac. If you want lesser-known Bordeaux at a more accessible price point, Chateau Biac or Haut Bailly.” — Carrie Lyn Strong, Wine Director/Sommelier, Casa Lever, NYC

Donate: Carrie Lyn Strong Venmo

“If you are a fan of Bordeaux, I recommend looking to Southwest France for value wines. Buzet, a small appellation known for its Merlot and Cabernet blends, offers really great wine for a fraction of the cost that you would pay for great Bordeaux. [The] 2016 Mary Taylor Wines Buzet punches above its weight. You get those wonderful aromas of tobacco, black fruit, and leather that invoke Right Bank comparisons. It retails around $18.” — Etinosa Emokpae, Wine Director, Friday Saturday Sunday, Philadelphia

“Château Beauséjour ‘Pentimento,’ Montagne-Saint-Émilion. This wine tells a story. It’s made by the first American female making wine in Bordeaux. I had the pleasure of working with the winemaker, Michelle D’ Aprix, at Bin 14 wine bar when she was traveling to France several times in the year to produce her first vintage. It is named Pentimento after one of her favorite books, “Pentimento,” by playwright Lillian Hellman. Just like the memoir muses on the people and experiences that have had a profound influence on her life, Michelle felt the same with her first wine label. The wine is farmed and made using little to no intervention for each vintage. [It’s] a wine that can be enjoyed upon release — no aging required — while pleasing Old World and New World palates alike.” — Madeline Maldonado, Beverage Director, da Toscano, NYC

“Château Haut-Segottes Saint Emilion Grand Cru (Cabernet Franc, Merlot). [Chateau Haut-Segottes is] owned and operated by Danielle Meunier. Smoked cherries, cigar, and peppercorn make it feel distinctly Bordeaux. Great with rich and rustic food but still light enough for other cuisines.” — Emmanuelle Massicot, Assistant General Manager, Kata Robata, Houston

“White Bordeaux. Probably not what you were expecting, I know. But if you haven’t spent time drinking the white blends of Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, and Muscadelle from Bordeaux, you’re missing out. Graville-Lacoste Graves Blanc is a delicious blend of mostly Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc, with just a touch of Muscadelle.” — Theo Lieberman, Beverage Director, 232 Bleecker, NYC

Donate: 232 Bleecker Gift Cards

“This is a little tricky because the casual wine drinker tends to equate Bordeaux with unrivaled decadence and sophistication, which isn’t entirely untrue, but it’s certainly not the case across the board. The Cabernet-driven wines of Margaux aren’t the cheapest, but they’re consistent in texture, intensity, and quality.” — Kyle Pate, Sommelier, Tinker Street, Indianapolis

“2019 Château Le Bergey, Bordeaux, France ($12). Biodynamic and Bordeaux aren’t two words you often hear in the same sentence, unless you’re talking about this wine. It has everything you could want from a classic Cabernet-dominant blend and tastes like it should cost three times the amount — but doesn’t, which is great.” — Luke Sullivan, Head Sommelier, Gran Tivoli & Peppi’s Cellar, NYC

“Château Larruau, Margaux 2015 is an elegant and sophisticated Bordeaux that offers exceptional value. [The] estate is located next to Chateau Margaux, but the Larruau is a fraction of the price.” — Marsella Charron, Sommelier, The Harbor House Inn, Elk, Calif.

Donate: Alder Springs Vineyard “A Case for a Cause”

“Château La Garde from Pessac-Léognan in Bordeaux. Roughly equal parts Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, this wine explodes from the glass with violet, blackberry, and smoky notes. It’s structured and full with great minerality and firm tannins. Retails around $25.” — Matthew Pridgen, Wine Director, Underbelly Hospitality, Houston

“For value Bordeaux, I often go to the Côtes, but customers in the restaurant are often more familiar with Medoc, so I generally steer people to Château Castera. I’m fascinated by its history, dating from the Middle Ages, and I think being Merlot-predominant, it’s much more versatile [than] many Cab-based Bordeaux wines for pairing with multiple dishes. I generally can find this wine with a few more years on it than the current release of other wines, which customers appreciate.” — Jeff Harding, Wine Director, Waverly Inn & Garden, NYC

Donate: Jeff Harding Venmo

“Clos du Jaugueyron (any bottling). Bordeaux is big business. Dealing in large quantities can lead houses to make choices that sacrifice long-term vineyard health for short-term financial assurance. However, there are some winemakers who are doing things in a more old-school way, focusing on sustainability and rejecting chemical use — perhaps none better than winemaker Michel Théron of Clos du Jaugueyron. His entry level Haut-Medoc can be found for under $50 most places, while his top-of-the-line Margaux bottling will run you just shy of $100.” — Andrew Pattison, Beverage Director, Sushi Note, Los Angeles

“Château Biac is located in Cadillac, in the Entre-Deux-Mers. When the Asseily family acquired and revived the estate in 2006, the vineyards were rethought and now have dedicated old-vine blocks for Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Cabernet Franc. The wines are full-bodied and juicy! The structure and complexity definitely rival the growths of the Left Bank. For more bang for the buck, go for the Felix de Biac, the little sister to the flagship.” — Stefanie Schwartz, Sommelier, Portale, NYC

Donate: Stefanie Schwartz Venmo

“Best Bordeaux for the price — Château Potensac or Château Ormes de Pez.” — Zac Adcox, Advanced Somm, indo, St. Louis

Donate: The United Sommeliers Foundation

The article We Asked 15 Wine Pros: Which Bordeaux Offers the Best Bang for Your Buck? appeared first on VinePair.

source https://vinepair.com/articles/15-best-quality-bordeaux-brands-price/

0 notes

Text

We Asked 15 Wine Pros: Which Bordeaux Offers the Best Bang for Your Buck?

As one of the world’s premier wine regions, Bordeaux’s main focus is Cabernet Sauvignon- and Merlot-driven blends. While Cabernet Franc, Malbec, and Petit Verdot make regular appearances, the region is also known for producing small amounts of white Bordeaux, as well as the lusciously sweet wine known as Sauternes.

Bordeaux is divided into three regions — the rival Left Bank and Right Bank, and Entre-Deux-Mers — each with its own distinct terroir. As a result, deciphering Bordeaux’s many variations can be tricky. Add Bordeaux’s often intimidating prices, and it’s not hard to understand why oenophiles on a budget often shy away from its wines. However, a great bottle of Bordeaux doesn’t have to break the bank.

To ensure that approachable Bordeaux is on the radar for every drinker, VinePair asked wine professionals around the country which bottles of Bordeaux present the very best value.

As bars and restaurants continue to navigate the coronavirus pandemic and reopening phases, VinePair asked the bartenders and drinks professionals below to provide a virtual tip jar or fund of their choice. More resources for helping hospitality professionals are available here.

“Château d’Armailhac, Pauillac, Bordeaux, France 2016. One of the great values, especially when great older vintages can be found. An elegant Bordeaux with the technical expertise of the team behind Château Mouton Rothschild.” — Jhonel Faelnar, Wine Director, Atomix, NYC

“I think the wines of Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste have been getting increasingly better without huge jumps in the price for some time.” — Rusty Rastello, Wine Director, SingleThread, Healdsburg, Calif.

Donate: NAACP; The United Sommeliers Foundation

“This is an easy one… if you are looking for well-known, high-end Bordeaux — best bang I’d suggest [is] Brane Cantenac. If you want lesser-known Bordeaux at a more accessible price point, Chateau Biac or Haut Bailly.” — Carrie Lyn Strong, Wine Director/Sommelier, Casa Lever, NYC

Donate: Carrie Lyn Strong Venmo

“If you are a fan of Bordeaux, I recommend looking to Southwest France for value wines. Buzet, a small appellation known for its Merlot and Cabernet blends, offers really great wine for a fraction of the cost that you would pay for great Bordeaux. [The] 2016 Mary Taylor Wines Buzet punches above its weight. You get those wonderful aromas of tobacco, black fruit, and leather that invoke Right Bank comparisons. It retails around $18.” — Etinosa Emokpae, Wine Director, Friday Saturday Sunday, Philadelphia

“Château Beauséjour ‘Pentimento,’ Montagne-Saint-Émilion. This wine tells a story. It’s made by the first American female making wine in Bordeaux. I had the pleasure of working with the winemaker, Michelle D’ Aprix, at Bin 14 wine bar when she was traveling to France several times in the year to produce her first vintage. It is named Pentimento after one of her favorite books, “Pentimento,” by playwright Lillian Hellman. Just like the memoir muses on the people and experiences that have had a profound influence on her life, Michelle felt the same with her first wine label. The wine is farmed and made using little to no intervention for each vintage. [It’s] a wine that can be enjoyed upon release — no aging required — while pleasing Old World and New World palates alike.” — Madeline Maldonado, Beverage Director, da Toscano, NYC

“Château Haut-Segottes Saint Emilion Grand Cru (Cabernet Franc, Merlot). [Chateau Haut-Segottes is] owned and operated by Danielle Meunier. Smoked cherries, cigar, and peppercorn make it feel distinctly Bordeaux. Great with rich and rustic food but still light enough for other cuisines.” — Emmanuelle Massicot, Assistant General Manager, Kata Robata, Houston

“White Bordeaux. Probably not what you were expecting, I know. But if you haven’t spent time drinking the white blends of Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, and Muscadelle from Bordeaux, you’re missing out. Graville-Lacoste Graves Blanc is a delicious blend of mostly Semillon and Sauvignon Blanc, with just a touch of Muscadelle.” — Theo Lieberman, Beverage Director, 232 Bleecker, NYC

Donate: 232 Bleecker Gift Cards

“This is a little tricky because the casual wine drinker tends to equate Bordeaux with unrivaled decadence and sophistication, which isn’t entirely untrue, but it’s certainly not the case across the board. The Cabernet-driven wines of Margaux aren’t the cheapest, but they’re consistent in texture, intensity, and quality.” — Kyle Pate, Sommelier, Tinker Street, Indianapolis

“2019 Château Le Bergey, Bordeaux, France ($12). Biodynamic and Bordeaux aren’t two words you often hear in the same sentence, unless you’re talking about this wine. It has everything you could want from a classic Cabernet-dominant blend and tastes like it should cost three times the amount — but doesn’t, which is great.” — Luke Sullivan, Head Sommelier, Gran Tivoli & Peppi’s Cellar, NYC

“Château Larruau, Margaux 2015 is an elegant and sophisticated Bordeaux that offers exceptional value. [The] estate is located next to Chateau Margaux, but the Larruau is a fraction of the price.” — Marsella Charron, Sommelier, The Harbor House Inn, Elk, Calif.

Donate: Alder Springs Vineyard “A Case for a Cause”

“Château La Garde from Pessac-Léognan in Bordeaux. Roughly equal parts Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, this wine explodes from the glass with violet, blackberry, and smoky notes. It’s structured and full with great minerality and firm tannins. Retails around $25.” — Matthew Pridgen, Wine Director, Underbelly Hospitality, Houston

“For value Bordeaux, I often go to the Côtes, but customers in the restaurant are often more familiar with Medoc, so I generally steer people to Château Castera. I’m fascinated by its history, dating from the Middle Ages, and I think being Merlot-predominant, it’s much more versatile [than] many Cab-based Bordeaux wines for pairing with multiple dishes. I generally can find this wine with a few more years on it than the current release of other wines, which customers appreciate.” — Jeff Harding, Wine Director, Waverly Inn & Garden, NYC

Donate: Jeff Harding Venmo

“Clos du Jaugueyron (any bottling). Bordeaux is big business. Dealing in large quantities can lead houses to make choices that sacrifice long-term vineyard health for short-term financial assurance. However, there are some winemakers who are doing things in a more old-school way, focusing on sustainability and rejecting chemical use — perhaps none better than winemaker Michel Théron of Clos du Jaugueyron. His entry level Haut-Medoc can be found for under $50 most places, while his top-of-the-line Margaux bottling will run you just shy of $100.” — Andrew Pattison, Beverage Director, Sushi Note, Los Angeles

“Château Biac is located in Cadillac, in the Entre-Deux-Mers. When the Asseily family acquired and revived the estate in 2006, the vineyards were rethought and now have dedicated old-vine blocks for Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Cabernet Franc. The wines are full-bodied and juicy! The structure and complexity definitely rival the growths of the Left Bank. For more bang for the buck, go for the Felix de Biac, the little sister to the flagship.” — Stefanie Schwartz, Sommelier, Portale, NYC

Donate: Stefanie Schwartz Venmo

“Best Bordeaux for the price — Château Potensac or Château Ormes de Pez.” — Zac Adcox, Advanced Somm, indo, St. Louis

Donate: The United Sommeliers Foundation

The article We Asked 15 Wine Pros: Which Bordeaux Offers the Best Bang for Your Buck? appeared first on VinePair.

Via https://vinepair.com/articles/15-best-quality-bordeaux-brands-price/

source https://vinology1.weebly.com/blog/we-asked-15-wine-pros-which-bordeaux-offers-the-best-bang-for-your-buck

0 notes

Text

It was while attending the current revival of Lillian Hellman’s 1936 play “Days to Come,” which is set during a strike at a brush factory in Ohio, that I suddenly wondered: Where are the American plays about unions, or workers, or even just workplaces?

It seems an apt question for Labor Day, which, contrary to what may be public perception, was not created to promote barbecues. Congress passed a law making Labor Day a legal holiday in 1884 to celebrate the labor union movement, a holiday first proposed by a labor union official

To The Bone,2014: Liza Fernandez, Annie Henk and Lisa Ramirez working in the poultry plant

Waiting for Lefty, 1937

When Mañana Comes, 2014. Jose Joaquin Perez, Jason Bowen, Brian Quijada and Reza Salazar as busboys in “My Manana Comes”

The worker, bloodied, toting a gun, in “Days to Come”

A Taste of Honey, 1961 Broadway, with Angela Lansbury and Joan Plowright.

Assistance, 2012

Sweat on Broadway: Alison Wright, Will Pullen, Michelle Wilson

Gloria, 2015

Jason Dirden and Nikiya Mathis in Skeleton Crew

Looking at the list put together recently by the theater critics of the New York Times of the best 25 plays in the last 25 years, only two of the plays could reasonably be considered workplace dramas (and even that a stretch) – The Flick, about movie house ushers, and The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity, about wrestlers. None of the 25 focus on unions.

But even in Entertainment Weekly’s 2013 list of the 50 best plays of the past 100 years, only Arthur Miller’s 1949 “Death of A Salesman” and Sophie Treadwell’s 1928 “Machinal” give us a sense of what working life is like in America.

The truth is, there are plays about workers. “Days to Come” was not successful when it debuted on Broadway; it lasted just seven performances. But one of the biggest hits of the 1930’s, “Waiting for Lefty” by Clifford Odets, presented a meeting of cab drivers who are planning a labor strike– and included the audience as if part of the meeting. The play was produced on Broadway (at the Longacre and then the Belasco) in 1935 by the Group Theater for a total of 168 performances, but then spread to theaters (and union halls) across the country.

In the last few years, I’ve seen several fine plays specifically about the taxing conditions of workers in various workplaces – in 2014, To The Bone, a play by Lisa Ramirez about Latina workers in an upstate chicken slaughterhouse and My Manana Comes, Elizabeth Irwin’s play about the kitchen staff in a fancy Manhattan restaurant; in 2015, Gloria by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins took place in the offices of a publication similar to the New Yorker magazine (which is where Jacobs-Jenkins once worked.) The copy editors and office workers in this play do not fit into American conventional notions of working class, but workplace issues are not limited to blue collar workers; the story revolves around one undervalued worker being driven to a shocking act of violence. Another such play about white collar workers is entitled Assistance, which Leslye Headland wrote in 2008, and I saw in 2012, and which became startlingly relevant in 2017: It is about the mistreatment of the office staff by a thinly-veiled character clearly based on Harvey Weinstein.

And then in 2016, there were the stellar examples of Dominique Morisseau’s play Skeleton Crew, about the mostly African-American workers in a dying auto services plant in Detroit, and Lynn Nottage’s “Sweat,” about the social and economic breakdown of a group of friends of varying ethnicities in Reading, Pennsylvania with the decline of the local factory.

In none of these recent plays do I recall a union being a part of the story (certainly not a central factor) But even just as worker or workplace dramas, such plays are the exception; few are heralded or emulated. This arguably reflects what seems to have become an American consensus. Many of us don’t value “the worker” the way earlier generations did; don’t even identify as “workers”; minimize workplace stresses and inequities; and don’t see unions as a solution.

The numbers tell the story. At their peak in 1954, almost 35 percent of all U.S. wage and salary workers belonged to unions, according to the Congressional Research Service. By 1983, according to the Department of Labor, that percentage had decreased to 20 percent. In 2017, it was under 11 percent.

“Is our theatre now inescapably middle-class? “ English drama critic Michael Billington asked in The Guardian five years ago, lamenting the loss of “unpatronising portrayal of working-class life” in so-called “kitchen sink” plays such as Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey (which was produced on Broadway in 1960 starring Angela Lansbury, Joan Plowright and Billy Dee Williams)

Yet, the theater – actors, stagehands, designers, – are disproportionately members of unions. Actors Equity was formed in 1913, and held its first strike in 1919. “The producers looked upon actors as silly children,” recalled Tallulah Bankhead, “vain, illogical, capricious, even slightly demented. How could artists hope to function in something so plebeian as a union?”

Some producers may still think so, but 105 years later, Actors Equity is still going strong, representing more than 48,000 actors and stage managers.

Many in the theater community surely understand firsthand that our “gig economy,” that our “digital age,” hasn’t made the labor movement obsolete; it’s made it more important.

“Sweat,” though it won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, ran just under four months on Broadway. But listen up and take heart: In the first project of the Public Theater’s Mobile Unit National, from September 27th to October 23rd, an 18-stop tour of Lynn Nottage’s play will travel through Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota — all states with districts up for grab in the midterm elections. This is not a coincidence. It is a movement.

Plays for Labor Day. In praise of theater about unions, workers and workplaces. It was while attending the current revival of Lillian Hellman’s 1936 play “Days to Come,

0 notes