#archeologists

Text

The Turoe Stone

The Turoe Stone sculpture is a masterpiece of Irish Iron Age art and normally stands in the village of Bullaun near Loughrea, Co Galway. It had been moved in the 1850s from its original location near the Rath of Feerwore, an Iron Age ring-fort structure, at nearby Kiltullagh. The stone is currently off site and in the hands of the Office of Public Works for essential remedial work and unavailable…

View On WordPress

#Ancient Celts#Archeologists#Bullaun#Celtic Art#Cloch an Tuair Rua#Co. Galway#France#Greece#Ireland#Iron Age#La Téne#Legend of the Celtic Stone#Loughrea#Newgrange#Sculpture#The Stone of the Red Pasture#The Turoe StoneEdit "The Turoe Stone"

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

"when archeologists dig your skeleton up they'll see your bones were female/male"

A) trans skeletons are able to be identified by archeologists so not really sweetie

B) im not exactly significant enough for someone to graverob my fucking corpse up and play with my bones at random

C1) if an archaeologist is peeking at my bones its probably been very fucking long from my death and i wont give a shit because (you guessed it) I'll be dead!

C2)Plus thats alot of time for technology to advance and I'll assume people would have at least gotten to the point of consistently being able to match a record to some bones and will see who i was.

C3) If not? No biggie i dont give a fuck I'm more stoked about the sociologists and historians finding out who i was.

C4) is a fucking explosive

#trans jokes#archeologists#archeology#archeologist#trans#nonbiney swag competition#nonbinary#enby#enby pride#autism#meme#c4 explosive#c4

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ancient Egypt had archeologists.

That’s it. That’s the history fact.

-History Anon

Ancient Egypt had archeologists?

That is like...like legit that's mindblowing!

#ask scott lang#scott lang#ant-man#history anon#history lesson#ancient egypt#archeologists#ant man#antman

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archeologists about to bust open this guy's 4000 year old tomb reading this inscription:

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excavated Canaanite High Place: "the sin of the Amorites"

In 1902, archaeologist Stewart Macalister began excavating at Gezer. He soon realized that he was digging a Canaanite high place where the ancient inhabitants of the city had worshipped their gods. There he unearthed deeply disturbing evidence for “the iniquity of the Amorites,” which corroborated the Canaanite worship practices described in the Bible.

youtube

#archeologists#archeological discoveries#real history#history#truthseeker#bible#jesus christ#christianity#scriptures#jesussaves#biblescripture#testimonies#Youtube

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

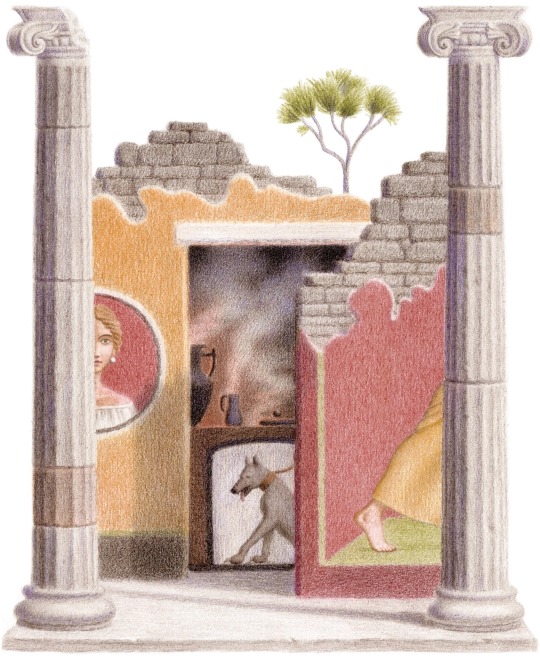

Pompeii Still Has Buried Secrets

The first major excavations in decades shed light on how ordinary citizens shopped and snacked—and where slaves slept.

— By Rebecca Mead | Published November 22, 2021 | Friday June 30, 2023

The ancient city was two miles in circumference. A third of it is still unexcavated. Illustration By Daniele Castellano

The journey from Naples to the ruins of Pompeii takes about half an hour on the Circumvesuviana, a train that rattles through a ribbon of land between the base of Mt. Vesuvius, on one side, and the Gulf of Naples, on the other. The area is built up, but when I travelled the route earlier this fall I could catch glimpses of the glittering sea behind apartment buildings. Occasionally, the mountainous coast across the bay came into sight, in the direction of the old Roman port of Misenum—where, in 79 A.D., the naval commander and prolific author Pliny the Elder watched Vesuvius erupt. Pliny, who led a rescue effort by sea, was killed by one of the volcano’s surges of gas and rock; his nephew, Pliny the Younger, provided the only surviving eyewitness account of the disaster. My view sometimes opened up in the opposite direction, toward the volcano, to reveal farmland or a stand of umbrella pines, their tall trunks giving way to billowing needle-covered branches. Pliny the Younger compared the shape of these trees to the volcanic eruption, with its column of smoke rising to a puffy cloud of ash that hovered, and then collapsed, burying a good part of what is now the Circumvesuviana’s route.

I got off at the stop called Pompeii Scavi—“the ruins of Pompeii”—and headed toward the modern gates that surround the ancient city. Before Pompeii was drowned in ash, it had a circumference of about two miles, enclosing an area of some hundred and seventy acres—a fifth the size of Central Park. Its population is estimated to have been about eleven thousand, roughly the same number as live in Battery Park City. After the ruins were rediscovered, in the mid-eighteenth century, formal excavations continued throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, with successive directors of the site exposing mansions, temples, baths, and, eventually, entire streets paved with volcanic rock. About a third of the ancient city has yet to be excavated, however; the consensus among scholars is that this remainder should be left for future archeologists, and their presumably more sophisticated technologies.

At some ancient Roman sites, such as nearby Herculaneum, unexcavated areas have been topped with contemporary buildings. But at Pompeii, once you walk inside the gates, you can almost block out the modern world: the ancient city is full of spectacular vistas, with the straight lines of its gridded streets leading to Vesuvius in the distance. And, every so often, a visitor comes across a street or an alleyway that dead-ends at a twenty-foot-high escarpment covered with scrubby grass. This is the boundary between Pompeii’s revealed past and its still buried one.

I had come to Pompeii to explore one such boundary, at the abrupt terminus of the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento—the Street of the Silver Wedding—in a corner of what archeologists have designated as Regio V, the city’s fifth region. For many years, the formal excavations stopped here, just past one of Pompeii’s grandest mansions: the House of the Silver Wedding, which was uncovered in the late nineteenth century and named, in 1893, in honor of the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of the Italian monarch, Umberto I, and his wife, Margherita of Savoy. The spacious house, which is believed to have belonged to a Pompeiian bigwig named Lucius Albucius Celsus, included a salon fitted with a barrel-vaulted ceiling supported by columns of trompe-l’oeil porphyry, and an atrium, decorated with frescoes, that scholars regard as the finest of its kind in the city.

In the ruins of Pompeii, discovery has often gone hand in hand with destruction. Photograph by Michele Amoruso/Getty

I discovered that the mansion was closed for renovations: the clattering of workmen emanated from behind its high brick walls. But I wasn’t too disappointed—my interest was in what lay just beyond it, at a newly exposed crossroads. This is the site of the first significant excavations in decades of ruins embalmed by the 79 A.D. eruption. Since 2018, restoration work has been under way in Regio V to reshape and shore up the escarpment. Made up of impacted ash and lapilli, or pebbles of pumice, it had become increasingly vulnerable to collapse, especially after heavy rain. (When chunks of the escarpment broke off, artifacts and structures buried inside it were often obliterated.) Collapses aside, the weight of the unexcavated land in Regio V put the adjacent excavated area at risk by exerting immense pressure on exposed walls, some of which date to the first or second century B.C. The fragile escarpment threatened to make a ruin of the ruins.

Through a careful combination of archeology and engineering, the escarpment has been reshaped into a more gradual slope, with an exposed surface of rocky fragments secured by sturdy mesh. In order to lessen the gradient, it has been necessary to unearth a small area of previously buried streets and structures. In recent decades, most archeological excavations at Pompeii have been of layers that predated the first-century city—digging down to reveal, for example, that several of the town’s temples were built on structures that dated to the sixth century B.C. The new excavations in Regio V—conducted with the latest archeological methods, and an up-to-the-minute scholarly focus on such issues as class and gender—have yielded powerful insights into how Pompeii’s final residents lived and died. As Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, a professor emeritus at Cambridge University and an authority on the city, told me, “You only have to excavate a tiny amount in Pompeii to come up with dramatic discoveries. It’s always spectacular.”

My guide to the restorations of Regio V was Gabriel Zuchtriegel, who this past February was appointed the director of the Archeological Park of Pompeii. Forty years old, the German-born Zuchtriegel was formerly the director of the archeological site at Paestum, forty-odd miles south of Pompeii. As we walked around Regio V, he deftly navigated the uneven roads and talked about ongoing work: “We are not going to excavate just for the sake of excavating. It would be very problematic, and somehow irresponsible.” However, in the course of stabilizing this stretch of the boundary, in 2019, archeologists realized that they had come upon a structure worthy of a full excavation: a thermopolium, or snack bar, which was situated just across the street from the House of the Silver Wedding, as if the Frick mansion were cheek by jowl with a Gray’s Papaya.

The thermopolium, which opened to visitors in August, is a delight. A masonry counter is decorated with expertly rendered and still vivid images: a fanciful depiction of a sea nymph perched on the back of a seahorse; a trompe-l’oeil painting of two strangled ducks on a countertop, ready for the butcher’s knife; a fierce-looking dog on a leash. The unfaded colors—coral red for the webbed feet of the pitiful ducks, shades of copper and russet for the feathers of a buoyant cockerel that has yet to meet the ducks’ fate—are as eye-catching now as they would have been for passersby two millennia ago. (Today, they are protected from the elements and the sunlight by glass.) Another panel, bordered in black, is among Pompeii’s most self-referential art works: a representation of a snack bar, with the earthenware vessels known as amphorae stacked against a counter laden with pots of food. A figure—perhaps the snack bar’s proprietor—bustles in the background. The effect is similar to that of a diner owner who displays a blown-up selfie on the wall behind his cash register.

It turns out that few of Pompeii’s more straitened residents had a place at home to cook. “Rich people had kitchens in their houses, and banquet rooms and gardens,” Zuchtriegel told me, as we walked around the thermopolium. “But most inhabitants didn’t live in such places—they had small apartments, or even one-room flats. During the daytime, their place was a shop or a workshop, and at night the family would just close up the front and sleep there. And, when they could afford it, they would come here and have a warm meal, and take their plate and eat it on the street.”

Several tourists were peering through the glass into the thermopolium, as if they were hungry Pompeiians surveying the fare on offer. Zuchtriegel took a step back, toward a fountain; it would have provided fresh water for drinking, bathing, or cooling down. “It was life on the street, as today we can still see in Naples,” he said.

In 2018, a fresco of Cupid was discovered inside a sumptuous, newly excavated villa that has been named the House of the Garden. Photograph by Carlo Hermann/Getty

The thermopolium on the Vicolo delle Nozze d’Argento is far from unique—through the centuries, about eighty such establishments have been identified in Pompeii. But archeological science is now more evolved, Zuchtriegel told me, and at the new site scholars “can use modern technologies and methodologies to analyze what was inside the pots.” Fragments of duck bone were discovered in one of the containers, which are known as dolia, suggesting that the paintings of ducks served not just as decoration but as advertising. In other dolia, scholars found traces of cooked pig; what appears to be a stew of sheep, fish, and land snails; and crushed fava beans. A book of recipes attributed to Apicius, a celebrated Roman gourmet from the first century A.D., explains that “bean meal” can be used to clarify the color and flavor of wine.

These near-invisible remains of foodstuffs do not just provide information about the diet of Pompeii’s working classes. According to Sophie Hay, a British archeologist who has worked extensively at Pompeii, they also shed new light on the rhythms of civic life. “Up until this bar was excavated, people who study these things have gone around believing that the dolia contained only dry foodstuffs,” she told me. “There are Roman laws that said bars shouldn’t serve this kind of warm food, like hot meat, so we’ve been guided by the classical sources. Then, suddenly, there is this one bar that is definitely serving hot food. And is it the only bar in the Roman world to have done this? Unlikely. So that is huge.” A new story appears to be emerging from the lapilli: of a cunning bar owner who reckons that an authority from distant Rome isn’t likely to shut down his operation, or who is confident that the local authorities—the kind of Pompeiians who live in grand houses—will turn a blind eye to an illegal takeout business that keeps their less affluent neighbors fed with cheap but tasty fish-and-snail soup.

A decade or so ago, a different story about the walls of Pompeii prevailed—that they were crumbling from neglect and from the ineptitude of the site’s custodians. In late 2010, a stone building known as the House of the Gladiators imploded after heavy rains, severely damaging valuable frescoes inside. That disaster was followed by the collapse elsewhere in the city of several other walls. The media responded with a wave of alarmed stories; a typical headline, from National Geographic, asked, “pompeii is crumbling—can it be saved?” Italy’s President at the time, Giorgio Napolitano, declared the condition of Pompeii “a shame for Italy.” Pompeii was also afflicted with human corruption, with the Camorra—the Neapolitan Mafia—exerting influence over its custodial ranks and on the local businesses that catered to the 2.3 million tourists who visited annually. In 2012, the European Union intervened, underwriting the Great Pompeii Project, which offered a hundred and forty million dollars to Pompeii for conservation and restoration.

Despite this narrative of decline—much of which presumed that Italy was unwilling, or unable, to take care of its greatest asset, its cultural patrimony—the deterioration at Pompeii was inevitable. In some instances, what had given way and caused walls to crumble were not bricks laid by ancient Romans but concrete restorations carried out after the Second World War, during which Pompeii was assaulted by Allied forces who mistook corrugated-metal roofs covering excavation sites for Nazi barracks. Mary Beard, a professor at Cambridge University who is among the Anglophone world’s best-known interpreters of Roman history, told me, “The fate of Pompeii is quite mythologized, and has become a shorthand symbol for lots of other issues in heritage management. The P.R. used to be ‘Well, we can’t even keep Pompeii up, the place is falling down, it’s a terrible disgrace.’ Of course the place is falling down—it’s a ruin. There are totally unreasonable expectations of what Pompeii can be, and how it can be preserved.”

In 2014, the archeologist Massimo Osanna was appointed director of Pompeii, and he immediately launched an effort to restore confidence in the future of the ancient past. Sophie Hay told me, “I went to Pompeii shortly after Osanna got the job, and after five minutes on the site with him I got the idea of where he was going. He walked down the main street, the Via dell’Abbondanza, and there was all this horrible plastic netting in the doorways of buildings, the sort used on building sites to keep people out.” The site looked bandaged and bruised. “He was absolutely horrified—he called people over who were working there and said, ‘Can’t we just remove all of this?’ ” Osanna made Pompeii more inviting to visitors, and by 2019 their numbers had swollen to four million annually. That year, the House of the Gladiators reopened to the public after a reconstruction of its damaged frescoes, becoming a symbol not of Pompeii’s decline but of its renewed vitality.

Meanwhile, the charismatic Osanna won over the press by trumpeting discoveries resulting from the restoration work in Regio V. “He was absolutely brilliant at it,” Beard told me. “Without actually doing any major excavation, he gave a series of carefully timed bits of good news.” A headless male skeleton was discovered at a crossroads next to the House of the Silver Wedding, as was a huge block of stone, which lay, almost cartoonishly, right where the skull should have been. (The gruesome suggestion that the man had been decapitated was overturned by later analysis, which suggested that he had been suffocated by the pyroclastic flow—superheated rock, ash, and gases that rushed down Vesuvius’s flank.) In a house that had been buried beneath a swath of rough land, a fresco depicting the god Priapus weighing his oversized member on a scale was uncovered. The press hailed the new discoveries, and in 2020 Osanna was named director general of Italy’s state-run museums.

One day during my visit to Pompeii, I was wandering alone when I came upon the house with the Priapus, which is around the corner from the House of the Silver Wedding, on the Via del Vesuvio. The fresco of the erect god was in the entrance hall. Phallic imagery was common in Pompeii, and according to scholars such images were usually seen as symbols of good luck, rather than of ostentatious lewdness. It would have been interesting to know whether Priapus’ facial expression was one of pride or discomfort, but the fresco was missing the disk-shaped area where his head had once been. In a nearby room, a better-preserved painting depicted the mythical story of Leda and the Swan, in which Zeus assumes the form of a bird and copulates with a Spartan queen. After archeologists discovered the painting, in late 2018, and peeled back its curtain of gray, crumbly lapilli with scalpels, Osanna unveiled it to the public by describing the “pronounced sensuality” of Leda, who, he declared, was “welcoming the swan into her lap.” Examining the painting, I decided that Leda could just as easily be said to have an expression of trepidation, even panic.

Archeologists have since excavated the room to which the painting belonged: a small, richly decorated chamber featuring wall panels festooned with floral motifs. The lower half of the walls were painted in the rich red color indelibly associated with Pompeii. This look is consistent with what historians have classified as the city’s Fourth Style, which was prevalent in the years immediately before the cataclysm. The décor—now nearly two thousand years old—had been freshly installed when the volcano exploded.

In 2019, archeologists realized that they had come upon a structure worthy of a full excavation: a thermopolium, or snack bar, replete with still vivid paintings and amphorae. Photograph by Patrick Zachmann/Magnum

Since the remains of Pompeii and the other ancient Roman settlements inundated by Vesuvius first came to light, some three hundred years ago, discovery has often gone hand in hand with destruction. An eighteenth-century visitor to the site of Herculaneum described the methods used by the workmen under the command of Roque Joachim Alcubierre, the artillery engineer who had been appointed to oversee the excavation by the Bourbon monarchy then ruling the Kingdom of Naples. Unlike Pompeii, Herculaneum was not blanketed with ash and pumice; it was buried only by a series of pyroclastic flows, which hardened into a layer of deep rock, through which workmen could dig narrow tunnels only with great difficulty.

The workmen of that era, upon finding a mansion or other building, would extract any objects of obvious value, such as marble statues, bronze lamps, and decorative mosaics, without taking note of their location or of the architectural context. Because of the treacherous conditions—among them, inadequate light and air—workmen did not trouble to excavate doors. They broke through walls to get from one room to another, regardless of what decorations in the adjoining room they might be destroying. At Pompeii, it is not uncommon to see a wall with a hole smashed through it, including the wall perpendicular to the Leda and the Swan, where another painting has been partially destroyed—the handiwork of heedless laborers in centuries past, who dug down and rooted around through the ash and lapilli, which is shallower and easier to penetrate than the rock of Herculaneum.

Alcubierre operated with barbaric efficiency, especially when it came to wall paintings that his workers hacked off from their brick underpinnings. When a painting was deemed insufficiently different from those already unearthed, workmen pulverized it underground. These excavations were focussed on finding masterpieces to augment royal or aristocratic collections, rather than on discovering the mundane objects of everyday life—or material evidence of the complexities of Roman social structures. Today’s archeologists are happy to retrieve beautiful objects, but they are also intent on finding clues that will help them better understand how slavery functioned in the Roman world, or how women could acquire power.

Even the best-intentioned archeologists are only as good as their methodologies, and the primitive approaches of eighteenth-century pioneers are sometimes enough to make a modern observer shudder. In the seventeen-fifties, a large villa near Herculaneum was discovered, and archeologists were so transfixed by its handsome courtyards and garden that they barely registered the lumps of blackened charcoal that workmen were tossing aside. Many had crumbled before the lumps were belatedly identified as charred scrolls of papyrus. Did they record any lost works of antiquity? The first efforts to render the scrolls legible—by soaking them in mercury, or dunking them in boiling water—resulted in the scrolls turning to dust or mush. In a potent example of the advantage of waiting a few hundred years for technological advances to occur, scientists are now hoping to develop techniques for reading carbonized scrolls virtually, using microscopic-imaging tools devised for use in the drug and chemical industries.

Archeological techniques became more sophisticated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and at Pompeii there was a breathtaking innovation. Preserved in the compacted ash were numerous oddly shaped holes, and artisans made plaster casts of these cavities, thereby creating vivid representations of the city’s residents in their final moments: writhing helplessly on the ground, seeking to protect a loved one from the rain of ash. But Pompeii’s rising popularity as a tourist destination paradoxically contributed to the site’s erasure. Charles Dickens, who visited in 1844, writes, in “Little Dorrit,” about a family of tourists who made off with pocketed fragments—“morsels of tessellated pavement . . . like petrified minced veal.”

Less than a century after Dickens’s visit, much of the buried city had been unearthed, largely under the watch of Amedeo Maiuri, Pompeii’s director from 1924 to 1961. At the bidding of Mussolini, who sought to connect the grandeur of ancient Rome with the triumphs of contemporary Italy, Maiuri significantly accelerated the pace of excavation, exhuming residential areas of the city, and also the buildings that lined the Via dell’Abbondanza. The scale of activity made it hard to protect the site from weeds and looters. But experts praise Maiuri for having a scholarly interest not only in grand houses but also in the simpler structures—workshops, brothels, public latrines—that have increasingly become a focus of Pompeii scholars.

About a third of Pompeii has yet to be excavated; the consensus among scholars is that this remainder should be left for future archeologists, and their presumably more sophisticated technologies. Photograph by Patrick Zachmann/Magnum

Astonishingly, the new excavations in Regio V have prompted historians to reconsider one of the fundamental facts they thought they knew about Pompeii: the date of the eruption. In Pliny the Younger’s first-person account, he writes that the disaster occurred on August 24th. But, in a house down the street from the newly discovered thermopolium, archeologists have found a wall bearing the charcoal inscription of a date: the Roman equivalent of October 17th. Though the inscription doesn’t include a year, many scholars suspect that it dates from 79 A.D. Paul Roberts, a Pompeii scholar at the Ashmolean Museum, at Oxford University, told me, “Charcoal doesn’t tend to hang around too long. I am quite convinced that this was put on the wall not long before it was buried.” The inscription backs up a theory that another former director of Pompeii, Grete Stefani, proposed in 2006: that the correct eruption date was late October. Stefani based her argument on an array of archeological evidence, including the discovery of fruit that would have been out of season in August.

The charcoal marking is in a newly excavated residence that has been named the House of the Garden, because it once featured a lovely, verdant courtyard surrounded by a low wall decorated with images of plants. I visited it not long before the site closed for the day, when the declining sun was casting slanted light over Pompeii’s largely emptied streets, tinting the clouds beyond Vesuvius a gorgeous gold-pink. The inscription, at eye level on a wall, had a makeshift shield propped in front of it, protecting it from light damage. When a custodian removed the shield to show me the writing, I found it both indecipherable and disconcertingly familiar—it was the jotting of someone keeping track of housekeeping, just as I might use a whiteboard calendar to note a forthcoming appointment with the dentist.

The other rooms of the mansion were sumptuous, especially one in which a round fresco of a woman’s face—handsome, with deep-set eyes and a long, straight nose—looked out from a wall. Perhaps it was a portrait of the lady of the house. During the excavation of the mansion, a horrifying scene had been found: the skeletons of men, women, and children who had sought refuge in an inner room of the house, trying to shield themselves from the ash, the heat, and the gases spewed by the volcano. In the same building, archeologists discovered a box filled with amulets: figurines, phalluses, and engraved beads. In announcing the find, Massimo Osanna, ever the showman, had called it a “sorcerers’ treasure trove,” noting that the items contained no gold and therefore might have belonged to a servant or an enslaved person. Such items were commonly associated with women, Osanna had noted, and might have been worn as charms against bad luck.

Other scholars have warned that the suggestion of a sorcerer, or sorceress, verges on embellishment, given the paucity of material evidence. The contents of the box are now displayed in the Pompeii museum, with no mention of a sorcerer in the accompanying text. Yet, as the daylight dwindled in Pompeii, it was tempting to follow Osanna’s lead and imagine the scene: terrified members of the household clutching one another, their social differences levelled by disaster, as a Pompeiian who believed in dark magic made unavailing imprecations against unrelenting gods. My mystical vision evaporated, however, after the mansion’s custodian showed me another inscription, which had been scratched into the lintel of the house’s external doorway. It read “Leporis fellas”: “Leporis sucks dick.”

When Zuchtriegel, the current Pompeii director, was overseeing the site at Paestum, where three Greek temples have stood since the fifth and sixth centuries B.C., he made a number of innovations. Visitors were invited to watch ongoing excavations, and the storerooms inside the site’s museum were opened for public perusal.

Zuchtriegel told me that, in his leadership role at Pompeii, he intends to continue embracing new approaches. As we walked along the Via Stabiana, with its narrow, elevated sidewalks that helped Pompeii’s residents skirt the muck of its streets, he emphasized that archeology “is a field that is very much evolving, thanks to new discoveries and methodologies, but also thanks to new questions.” He went on, “Today, we have a much broader view of ancient society. Archeology started as a field dominated by male, upper-class, European, white scholars, and noblemen and connoisseurs, and this very much conditioned archeological research, and what people were interested in. Now, thanks to new perspectives—post-colonial studies, and gender studies, and feminism—we have a really different perspective on antiquity.”

Among the discoveries being examined through these new interpretative lenses was the first significant find announced under Zuchtriegel’s tenure: the remains of a man identified as Marcus Venerius Secundio. The tomb was found not in Regio V but east of Pompeii, where a necropolis had been unearthed close to one of the city gates. Unusually for an adult burial, the deceased had been embalmed rather than cremated, and the body was so well preserved that hair and even part of an ear were intact.

Secundio, Zuchtriegel explained, was a freedman, having formerly been a public slave—essentially, a municipal worker owned by the city. “Of course, nobody wanted to be a slave—it was very humiliating to be the property of someone,” Zuchtriegel said. “On the other hand, if you were a very poor freedman you were less well off than a household slave, some of whom were educators of the children of rich people, or secretaries who were part of the team that carried on the business of the owner.” It is unknown how Secundio gained his freedom, but historical records indicate that a public slave could raise funds to buy himself out of servitude. Evidently, Secundio ascended within Pompeiian society, becoming an augustalis, or a priest in the imperial cult—one of the few high-ranking positions open to men who were not freeborn. According to the funerary inscription on his tomb, Secundio was a patron of the arts, paying for ludi—musical or theatrical events that were performed in Latin and, significantly, in Greek. “This is the first time we have this direct evidence of Greek plays in Pompeii,” Zuchtriegel told me. Scholars had hypothesized, based on evidence in wall paintings and graffiti, that such events took place, but the inscription provides exciting confirmation.

In the decades before the eruption of Vesuvius, Zuchtriegel went on, there was a fashion in the Roman Empire for Greek-language performance, which was established by the emperor Nero, who ruled from 54 to 68 A.D., and who fancied himself not just an aficionado of Greek drama and song but also a performer. (According to the historian Suetonius, Nero “made his début” as a singer in Naples, so enjoying himself onstage that he ignored the rumblings of an earthquake in order to finish his performance.) Nero’s reputation as a tyrant has lately been reconsidered by scholars, and the evidence of Greek-language ludi in Pompeii buttresses the revised image of the Emperor as a popular leader; it also underscores the extent to which even a provincial city like Pompeii was influenced by the cultural fashions of the capital. “Pompeii and Campania had this really multicultural environment,” Zuchtriegel said. “People came from the Eastern Mediterranean, and there were the old Greek colonies at Naples and Paestum. We have evidence of Jewish people here at Pompeii.” (Graffiti found in the city cite individuals with the names Sarah, Martha, and Ephraim.)

Zuchtriegel told me that, as director, he intended to build on Osanna’s work, a decade after the rescue operation of the Great Pompeii Project was initiated. Other damaged fringes of Regio V are to be shored up, and new, limited excavations are to take place in another district, Regio IX. Similarly, work is continuing to protect areas outside the gates of Pompeii which have remained vulnerable to the incursion of illegal diggers. Scholars have made various new discoveries in these outlying areas, such as the remains of a horse that died during the eruption; the cavity formed in the rubble by the horse’s body has now been cast in plaster. Earlier this month, Zuchtriegel announced the discovery of slave quarters: a humble room, equipped with three wooden beds and amphorae stacked in a corner. “It is certainly one of the most exciting discoveries during my life as an archeologist, even without the presence of great ‘treasures,’ ” Zuchtriegel said. “The true treasure here is the human experience, in this case of the most vulnerable members of ancient society.”

But Zuchtriegel is likely to be less hyperbolic in his promotion than Osanna sometimes sought to be. I asked him how he could make preservation as exciting as discovery. He paused, then said, “Well, it doesn’t have to be so exciting. But we have to do it, anyway. I think what Massimo showed in these years is that excavation, research, and preservation are not opposites. As we see with the thermopolium, this was an excavation that had as a primary goal to preserve the conservation of the site.” He went on, “It’s very important to explain that archeology is very complex—from the excavation to the restoration to the exhibition, analysis, publication, and study. It’s important to make this transparent, and share it with the public, so that people understand that archeology is not about treasures and precious objects—that’s only a small part. It’s really about reconstructing the life of people in the distant past.”

Zuchtriegel and I wandered over to a section of the city that was closed to visitors. A custodian holding a bunch of keys seemed on the verge of warning us off when he recognized his relatively new boss. We then entered another of Pompeii’s grand mansions, the house of Maximus Obellius Firmus, one of the city’s most prominent citizens in the period before the eruption. This mansion also demonstrated the Pompeiian fascination with Greek culture, Zuchtriegel explained. An interior garden was surrounded by a peristyle—a rectangular perimeter of covered columns—which was popular in classical Greece. “There is an attempt to transform a traditional Roman house into a Greek space,” Zuchtriegel said. “You could be here in the middle of Pompeii, and feel like you were in a different space.”

He encouraged me to look upward. A restored rafter was serving as a perch for a few pigeons, whose droppings are especially damaging to wall paintings and stucco. Zuchtriegel had introduced a program whereby trained hawks sweep the ruins, frightening off the pigeons. “I did the same in Paestum,” he said. “You can reduce the pigeon population by eighty-five to ninety per cent!”

One of the challenges facing any director of Pompeii is coping with the tourists who flock, like pigeons, to explore the ruins. As Italy reopens for both domestic and international tourism, crowds are again lining up to enter Pompeii’s more celebrated locations, including the street-corner brothel in which partitioned chambers equipped with masonry beds are decorated with obscene wall paintings—an X-rated version of the dead ducks painted on the counter of the thermopolium in Regio V. A feminist interpretation of the practice of sex work, and its role in Pompeiian society, has not yet been incorporated at the site. An official guide who showed me around the city one day regaled me uncritically with the anecdote, found in the satires of the poet Juvenal, that Messalina, the wife of the emperor Claudius, liked to moonlight in a brothel—a story that Mary Beard and other contemporary critics view with a witheringly skeptical eye.

Counterintuitively, one of Zuchtriegel’s goals as director of Pompeii is to persuade visitors to go elsewhere—to the ruins of Herculaneum and to other, smaller sites that lie in the shadow of Vesuvius. One day, I got off the Circumvesuviana at Torre Annunziata Oplonti, and walked from the station for ten minutes through the town’s steep, scruffy streets to reach a site known as the Villa Poppaea—once a luxurious suburban domicile with views of the islands of Ischia and Capri. The villa gets its name from Nero’s second wife, Poppaea Sabina, whose family is believed to have come from Pompeii; it is thought to have been her country residence.

The site had just opened for the day, and I had it to myself as I descended to the 79 A.D. level and walked through a garden, where what looked like carbonized tree stumps remained in the ground. The villa, a sprawling complex of reception rooms and gardens and walkways which dates to the first century B.C., was stunning. First rediscovered at the end of the fifteenth century, when engineers were digging a canal, it was partially excavated in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, then more fully exposed in the late twentieth century. Archeologists cleared away pumice and ash, and in rooms edging a garden they uncovered magnificent frescoes of the birds and plants that appear to have once flourished there. A large, decorated peristyle surrounded another garden: Greek-style living at its finest.

For all the interest offered by the new discoveries of the modes of everyday living at Pompeii—with its snail stews and its Greek theatrics—an empty, unfamiliar, luxurious villa retains an irresistible allure. The grandeur of the Villa Poppaea brought to mind images of an élite class of individuals who thought themselves safely removed from the grubbing hardships endured by the poor, but whose vast wealth provided them with no protection from a titanic natural disaster. At the eastern perimeter of the site, there was a feature to stir the envy of a Silicon Valley plutocrat: a swimming pool more than sixty metres in length. It was filled with weeds and gravel now, but in 79 A.D. it would have been edged by lavishly decorated salons and gardens—and it was easy to imagine Roman aristocrats lounging around a glittering pool, gazing across the sea with the dormant mountain at their backs, confident that the world was—and always would be—theirs to enjoy. ♦

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketch #352

If you would like to stay updated on my weekly cartoons, consider checking out the DBCartoons Facebook or Instagram pages.

View On WordPress

#archeologists#cartoonists#drawing tips#funny cartoon#funny cartoons#funny cartoons sketch#how to draw#sketch#sketch challenge#sketch funny cartoon#sketch funny cartoons#sketch-a-day challenge#sketching

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transphobes: You might claim to be a woman, but when an archeologist finds your body they’re going to identify you as a man!!!

The Archeologist unearthing my body in 15232: Aurgh!!! A Sk-sk-sk Sk-Sk sk-Sk-sk-sk-sk-sk-SKELETON!!!!!!

#2016 presidential election#2022 Philip Election#transphobia#skeletons#archeologists#Trans#The archeologist is scared of the spooky skeleton#I hope that properly came across

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hot take aliens in movies don’t need to go undercover to learn about our world and our collective history because this place is just filled with scholars, educators, researchers, and individuals who have hyperfixations that are just dying to tell someone about what they like.

#aliens#history#scholars#archeologists#anthropology#butterfly... specialist#oceanographer#humans can physically not stop themselves from researching everything and everyone#then turning around and being like look at what i learned!#we have literally sent thousands of radio signals into the dark abyss of space#with our co-ordinates to our planet#for ANYONE#to listen too#simply because we want to learn about them and then also tell them about all our cool stuff

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ea Nasir

the year is 4982, archeologists finally salvage an internet-connected computer and can only recover tumblr.

A great schism happens between those who think their previous datations were greatly misguided and Ea-Nasir lived in the 21st century AD, not BC, and those who think Ea-Nasir was in fact an immortal, along with Keanu Reeves, who continued his mischiefs long after he was supposed to be dead.

In the corner, Keanu Reeves laughs to himself because he knows what happened.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alternative archeologists theorized that the huge megalithic stones used to build ancient sites were moved by sound. Do you think it would be possible to levitate giant stones using nothing but good vibrations?

#archaeology #grahamhancock #acousticlevitation #sound #history

#wolfenhaas#history#historyblog#sound#Acoustic levitation#Alternative archaeology#Archeologists#archaeology#Science#good vibrations

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

No one seemed to know the old lady who lived in the basement but scholars tend to think she was a descendant of her parents. This was pure speculation, however, fueled mainly by the recent discovery of an amber statue of the Queen that turned out to be just an old Mrs Butterworth bottle.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

SpaceTime Series 26 Episode 153

*New mission for NASA’s OSIRIS-Rex spacecraft

After completing its initial seven year sample return mission to the asteroid Bennu, NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft is moving on to a new mission studying the asteroid Apophis.

*Discovery of planet too big for its Sun

Astronomers have discovered a planet that is far too massive for its host star. The finding reported in the journal Science calls into question what was previously understood about planetary formation

*Halley's comet reaches aphelion

On Saturday, December 9th comet 1P/Halley reached aphelion – it’s most distant orbital position from the Sun.

*The Science Report

Diet and air pollution remain among the biggest contributors globally to heart disease. Archaeologists have uncovered the oldest known fortified prehistoric settlement in the world.

A new study has found that Cats love to play fetch with their owners, especially if they're in charge. Skeptics guide to Meghan Markle’s anti stress patch

Listen to SpaceTime on your favorite podcast app with our universal listen link: https://spacetimewithstuartgary.com/listen and access show links via https://linktr.ee/biteszHQ

If you love this podcast, please get someone else to listen to. Thank you…

Your support is needed... **Support SpaceTime with Stuart Gary: Be Part of Our Cosmic Journey!**

SpaceTime is fueled by passion, not big corporations or grants. We're on a mission to become 100% listener-supported, allowing us to focus solely on bringing you riveting space stories without the interruption of ads. 🌌

**Here's where you shine:** Help us soar to our goal of 1,000 subscribers! Whether it's just $1 or more, every contribution propels us closer to a universe of ad-free content.

**Elevate Your Experience:** By joining our cosmic family at the $5 tier, you'll unlock: - Over 400 commercial-free, triple episode editions. - Exclusive extended interviews. - Early access to new episodes every Monday.

Dive in with a month's free trial on Supercast and discover the universe of rewards waiting for you! 🌠 🚀 [Join the Journey with SpaceTime](https://bitesznetwork.supercast.tech/) 🌟 [Learn More About Us](https://spacetimewithstuartgary.com)

Together, let's explore the cosmos without limits!

#astronomy #space #news #spacetime #podcast

#aphelion#archeologists#astronomy#cats#comet#discovery#halley's#mission#nasa#news#osirus-rez#planet#podcast#pollution#science#space#spacetime#starstuff#stuart#sun

0 notes

Text

youtube

పొడుగు ఆకారపు పుర్రెలతో ఉన్న గ్రహాంతరవాసులు, మానవులను జన్యుపరంగా మార్పు చేశారా? - ఎపిసోడ్ 2

So, ఈ పురాతన Astronauts చూడడానికి ఎలా కనిపిస్తున్నారు? ఇక్కడ, మీరు వాటిని చూడవచ్చు, అవును అవి పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెలను కలిగి ఉన్నాయి, ఇవి మనుషులుగా కనిపించడంలేదు. మనుషులకు ఇంత పెద్ద తలలు ఉండవు కదా? కానీ వారు ఏం చేస్తున్నారు? వారు చేతిలో పందిని పట్టుకున్నారా? పైన, మీరు మరింత crazyగా ఉన్నదాన్ని చూడవచ్చు, మనం పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెతో, మరొక జీవిని చూడవచ్చు, కానీ అది ఒక శిశువును పట్టుకొని ఉంది. ఇది ఒక crazy అయినా detail. ఇక్కడేమవుతోంది? గ్రహాంతర వాసులు, మనుషులను geneticalగా మార్పులు చేస్తున్నారా? ఈ జీవులు పిల్లలు మరియు జంతువులతో ప్రయోగాలు చేస్తున్నాయా? ఇందుకోసమే Placentaతో పాటు, శిశువు చెక్కడాన్ని మరియు బొడ్డు తాడుతో పాటు జీవితం ఎలా సృష్టించబడుతుందో వర్ణించారు? మరీ ముఖ్యంగా, పురాతన astronauts చూడడానికి ఇలానే ఉండేవారా? వారికి పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెలు ఉన్నాయా? పైన, మరో 2 బొమ్మలు ఉన్నాయి, వాటి ముఖాలు భారీగా వికృతీకరించబడ్డాయి, మళ్లీ అవి పొడుగు ఆకారంలో, తలలు ఉన్నట్లు కనిపిస్తున్నాయి. కానీ, పురాతన నిర్మాణదారులు, ఒకవేళ పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెలతో, ఈ జీవులను ఊహించుకుంటే ఎలా ఉంటుంది?

అంతే కదా? కాదు Archeologistలు అనేక పురాతన ప్రదేశాలలో, ఖననం చేయబడిన, అసలైన పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెలను కనుగొన్నారు. ఉదాహరణకు పెరూలో, వారు, ఒకటి రెండును కనుగొనలేదు, వారు చాలా కనుగొన్నారు. ఇది సాధారణ మానవ పుర్రె - మరియు ఇది పొడుగుచేసిన పుర్రె, ఇది వింతగా ఉందని నా ఉద్దేశ్యం. ఇతర పురాతన నాగరికతలు కూడా పొడుగుచేసిన పుర్రెల గురించి ప్రస్తావించాయి. ఇది, ఈజిప్ట్లో ఉన్న ఒక పురాతన విగ్రహం, ఇది దేవుని రాజు ఆఖెనాటెన్ మరియు అతని వారసులను చూపుతుంది - ఆ పుర్రె ఎంత పొడవుగా ఉందో చూడండి? కాబట్టి, ఈ ఇండోనేషియా ఆలయంలో ఉన్న, ఈ శిల్పాలు ఊహకు అందడం లేదు. దీన్ని చూడండి, ఈ పుర్రెలు చాలా పెద్దవి మరియు పొడుగుగా ఉన్నాయి. మధ్యలో ఉన్న ఈ వ్యక్తిని చూడండి, ఇది ఒక పెద్ద తల, మానవ తలలు ఇలా కనిపించడానికి అవకాశం లేదు. And ఇక్కడ చూడండి, అతనికి మరింత crazyగా ఉంది, అతని ముఖానికి నకిలీ గడ్డాన్ని attach చేశారు చూడండి. ఇది చూడడానికి అసలు గడ్డంలా లేదు, అతను నకిలీ గడ్డాన్ని ఎందుకు పెట్టుకున్నారు? ఈజిప్షియన్ గాడ్ కింగ్స్ పొడుగుచేసిన పుర్రెలను మాత్రమే కాకుండా, నకిలీ గడ్డాలు కూడా ధరించేవారని మీకు తెలుసా?

ఇది, పురాతన ఈజిప్టులో, నకిలీ గడ్డాలను ధరించడం ఒక ఆచారం, అయితే ఇండోనేషియాలో వేల మైళ్ల దూరంలో ఉన్న ఈ చెక్కడంలో మనం ఎందుకు చూస్తాము? ఆలయం ఖచ్చితంగా పురాతన పిరమిడ్లతో connect అయ్యి ఉంటుంది. కుడి వైపున ఉన్న ఈ బొమ్మను చూడండి, ఇది అతని పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న తల మాత్రమే కాదు, అతని ముఖం కూడా అలానే ఉంది, ఇది చూడడానికి మానవ ముఖంగా కనిపించడంలేదు, ఇది చాలా పదునుగా మరియు సూటిగా ఉంటుంది. అతను వేరే ఏదో అయ్యుంటాడని స్పష్టంగా తెలుస్తుంది. And ఈ బొమ్మని కూడా చూడండి, ఈ తల సాధారణమైనది కాదు, ఇది ఖచ్చితంగా పొడుగుగా ఉంటుంది. అవి హెల్మెట్లు అని మీరు అనుకోవద్దు, సమీపంలో ఉన్న శిల్పాలను చూడండి, ఇవి హెల్మెట్లు, కానీ ఇవి కాదు. ఇక్కడ చెక్కబడిన, ఈ బొమ్మల్లో చాలా వరకు పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెలు ఉన్నాయి. వారి యొక్క పొడుగు ఆకారంలో ఉన్న పుర్రెలు, ఇవి గ్రహాంతరవాసులని నిర్ధారిస్తాయా? ఆఫ్రికాలోని మాంగ్బెటు తెగల మాదిరిగా, కపాల వైకల్యాన్ని పాటించే వారు కేవలం మానవులే అయితే? వారు మానవులకు భిన్నమైన, ఇతర భౌతిక లక్షణాలను కలిగి ఉన్నారా? ఎవరికీ తెలియని విషయాన్ని నేను కనుగొన్నాను.

ఇక్కడున్న, ఈ గ్రహాంతరవాసుల పుర్రెలలో రంధ్రాలు ఉన్నాయి. ఈ బొమ్మను చూడండి, మీకు ఈ రంధ్రం కనిపిస్తుందా? అతని ఇయర్లోబ్ ఇక్కడ ఉంది, మరియు అతని చెవిపోగు చెవిలోబ్ నుండి వేలాడుతోంది. కానీ మనం ఇక్కడ, ఇయర్లోబ్ పైన, పుర్రెపై ఒక రంద్రాన్ని చూడవచ్చు. ఇది కేవలం, చెక్కడం పొరపాటు అని మీరు అనుకోవచ్చు, కదా? కాదు, తరువాత ఉన్న బొమ్మను చూడండి. మీరు దీన్ని చూస్తున్నారా? అతని చెవి లోబ్ పైన ఒక రంధ్రం ఉంది, కానీ మానవులకు వారి చెవి లోబ్స్ పైన ఇలాంటి రంధ్రం ఉండదు. And ఈ జీవులు, ఈ భౌతిక లక్షణాన్ని కలిగి ఉన్నాయి, ఇవి సరీసృపాల గురించి మనకు గుర్తుచేస్తున్నాయి - సరీసృపాలకు సరిగ్గా, ఈ ప్రదేశంలోనే రంధ్రం ఉంటుంది. ఇక్కడ అతని పుర్రె చూడండి, అది ఖచ్చితంగా పొడుగుగా ఉంది, కదా? ఇప్పుడు, ఈ ఆలోచనకు support ఇవ్వడానికి నేను ఈ carvingsను ఎంచుకుంటున్నానని మీరు అనుకోవడం నాకు ఇష్టం లేదు, కాబట్టి నేను మీకు చూపించిన మునుపటి శిల్పాలకు తిరిగి వెళ్దాం, పొడుగుచేసిన పుర్రెలతో ఉన్న, ఈ 3 బొమ్మలు గుర్తున్నాయా?

Praveen Mohan Telugu

#ancientaliens#elongatedskulls#candisukuhtemple#ancientastronaut#ancienttemple#ancientbuilders#archeologists#peru#egypt#egyptiangodkings#ancientsculptures#africa#combodia#angkorwattemple#sphagetty#pigrhinohybrid#indonesia#మననిజమైనచరిత్ర#hinduism#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Day Fossil Beds National Park

#national geographic#nature pictures#national park#iphoneography#landscape#archeologists#soil#land#landschaft#plate tectonics#photography#american history

0 notes