#and MSF clinic was attacked too

Text

Insult to Injury: The Director’s Cut — Chapter 01 [PREVIEW]

Note: Please view on the main blog page for an optimal reading experience. :D

Chapter One is about 95% revised to my liking. Here is a somewhat lengthier preview whilst work begins on 02 & 03.

June crawled by. Currently the MSF were in the process of dealing with a new influx of internally displaced persons (IDPs) from the surrounding prefectures and villages, all of whom had to be tested and separated from those not stricken with disease—as this did not necessarily mean they weren’t carrying others. Thanks to the cooperation with the local civilians and tireless efforts on part of the medical staff, there had been a forty-five-percent decrease in fatalities compared to the start of the year.

The atmosphere within the hospital was not improving. The topic of insurgence was the new favourite with patients. Allegedly there had been several attacks on neighbouring villages; a sign of impatience at the lack of tangible progress coupled with deep-seated mistrust of government officials. Now the Force Sécurité/Protection, or FSP, had been brought on in collaboration with an additional Protective Services Detail (PSD) by the name of Kerberos, to ensure the hospital and surrounding property remained untouched.

Their project coordinator called them all in for the sake of reviewing protocol in the event of an attack, starting to seem like more of a possibility. Criticism of the government’s method in handling the situation was discouraged during their meetings with the project coordinator. Madeleine was savvy enough to keep herself abreast of any controversy. For the rest of the Psychosocial Unit, she presumed they were either too naïve or willing to look the other way.

The only exception to this was the Vaccines Medical Advisor, Francis Karner; a stoic older man with thinning hair and glasses. He and Madeleine had cooperated a handful of times at the behest of the Medical Coordinator. Madeleine had found nothing wrong with his conduct. A diligent worker, he acknowledged her judgement fairly but did not overextend his gratitude. Outside of his work he was straight-laced and private. Whenever they had a break, he would often disappear frequently on calls. He’d been coming back tenser as of late and apologised to Madeleine.

“I was supposed to be sent home last month, but with the situation being what it is, I decided to stay on until things are resolved.” He did not sit down. “It’s madness. We’ve already waited until things are too severe to think of bringing in a proper security detail—who the hell does the project coordinator think we’re fooling?” Madeleine ignored him. “Dr Swann. The Medical Coordinator tells me you’ve been involved in volunteer work for a while.”

“Five years, as of March.”

“Perhaps they would be more willing to listen to someone with your expertise.”

“Well, it’s fortunate that I was not selected for my personal opinion.”

Karner chuckled. “You’ll go far.”

Madeleine had no interest in pursuing this topic any further. “Who were you speaking to?” Francis didn’t answer immediately. “Sorry. I shouldn’t have been so blunt. But you leave often enough and it appears to be taking a toll on you.”

“Just my wife. This past month has been no easier on her. But I find that it can help somewhat, just talking to someone outside of this element.” Madeleine nodded. Francis paused. “I’ve never seen you contact anyone outside of your unit.” Madeleine did not anticipate the conversation to take such a turn, nor did she particularly wish to divulge much about herself. But she could not deflect as she could in the clinic back home, and Francis seemed forthright enough to warrant a harmless response.

“I’m living with a friend. We graduated from college together.”

“And you keep in touch while you are abroad?”

“He tends to lead his own life while I am away.”

“That’s a great deal to ask of someone.” Madeleine inclined her head in his direction. This was not a man that emoted often; now the thin mouth was set, and the eyes behind the glasses disillusioned. “Few women your age would devote themselves to a thankless vocation. Not everyone is going to want to stick around until you decide you want to settle down.”

Madeleine’s smile did not touch her eyes. She hadn’t even mentioned the nature of her relationship to Arnaud. “We have an understanding, that’s all. Besides, I don’t bother him about his social life.”

Karner shook his head. In a few minutes the break subsided and they were back to work as usual. By the end of the day, Madeleine resolved to let him dig his own grave without further interference.

The next few days blurred together in her recollection. Karner made no attempt to converse with her. Madeleine found her mind snagging easily on technicalities. She became less tolerant of the Psychological Unit’s personal hang-ups with the lack of resources and lack of any obvious moral closure. Smell of rot and disinfectant permeated into her clothing and hair until she had begun to associate the smell itself with a total lack of progress.

She left the window to her hotel room cracked most nights, afraid to open it completely. Alone with her own mind and the recorder. The conversations now circled back readily to death and terrorism. An overwhelming fear of retaliation from insurrection.

It was just past one in the morning. In six hours she would return to Donka Hospital and repeat the process. A month and a half from now she would be on a flight back to Paris. Her mind refused to settle in either direction.

Outside her window she heard the distant voice of Francis Karner. He was conversing in German, from a few storeys down, but as Madeleine came over to the window she understood him clearly:

“…I’ve been saying it for weeks, and they dismiss me every time. These wounds are the result of prolonged exposure from chemicals. We’ve seen evidence of IDPs coming through, exhibiting the same symptoms as the PMCs we treated back in February. How we can expect to make any progress if the project coordinator refuses to bring this up? We’re putting God-knows how many lives at risk waiting for a vaccine that we don’t know if we need—and even so, it won’t be ready for another week. There’s not enough time to justify keeping silent….”

Madeleine closed the window carefully. She’d never been one to intrude on family matters.

⁂

When Madeleine exited her room the next morning, she found the project coordinator waiting for her in the hallway, along with the head of security from Kerberos and a couple Donka Hospital staff Madeleine knew by sight but not intimately.

The vaccines had arrived earlier than anticipated. Several members of the Medical Unit had stayed on-site in order to determine if all had been accounted for and subsequently realised it was rigged. Thanks to the intervention of the FSP the losses were minimal. Several doctors, including Herrmann, had suffered chemical exposure and were currently isolated from the rest of the IDPs to receive immediate medical attention. A few others, including Dr Karner, had been less fortunate.

Now there was additional pressure from the doctors and Logistics Team to begin moving the high-risk patients to a safer area. The fear that this story would circulate and any chance of obtaining vaccines would be discouraged could not be ruled out. So they would not be reporting this as a chemical attack to the government, but as an interception of an attack by local terrorists.

“Dr Swann.” The head of security, Lucifer Safin, gave Madeleine pause. His accent and complexion would presume a Czech or Russian background but he could have come from a variety of surrounding countries. The MSF on staff commonly referred to him by surname; perhaps Lucifer was simply an alias. What set him apart was his face. Gruesomely scarred from his right temple to the base of his left jaw, though the structure of his eyes and nose remained intact. In spite of the weather, she had never seen him without gloves. “I understand that you were one of the last to speak with Dr Karner?”

His manner wasn’t explicitly taciturn, more akin to the disconcerting silence one might experience while looking into a body of still-water—met only with your reflection.

“Yes,” said Madeleine, “but that was nearly five days ago.”

“You were instructed to monitor him during that period by the Medical Coordinator?”

“That’s correct.”

Safin glanced at the project coordinator. “I’ll speak with her alone.”

“Of course.”

Safin nodded. They walked down the length of the hall back to her room. His gait was purposeful and direct. He had a rifle strapped to him. Madeleine tried to avoid concentrating on it. Her attention went to the window. She had not locked it.

“Dr Swann.” The early morning light put his disfigurement into a new, unsettling clarity. Too intricate to be leprosy or a typical burn wound, it was more as if his very face were made of porcelain and had suffered a nasty blow, then glued together again. “What was the extent of your relationship to Dr Karner?”

“I did not work with him often. We talked once or twice but that was all. I have my own responsibilities with the Psychosocial Unit. From what I could tell, he never made an effort to befriend anyone.”

“You were asked to monitor Dr Karner. Why?”

“I was requested to do so on behalf of the Medical Coordinator. There were concerns that Dr Karner was somehow unqualified to continue his work. In observing him, I had no reason to suspect he was unfit for the position psychologically.” Safin said nothing. “The only issue I could see worth disqualifying him for, was that Karner and the project coordinator had very differing views on protocol.”

“He spoke to you about his views?”

“He expressed to me once, in confidence, that he did not understand the project coordinator’s hesitance to bring in a security detail.” Safin’s attention on her was razor-sharp, unwavering. She’d said too much. “He also told me he’d elected to continue volunteering here past his contract duration, just to ensure the operation was successful. That was my only conversation with him outside of a work-related context. You would be better off asking the other doctors about this.”

“We have video surveillance in place on the Grand Hotel de L’independence. At around one in the morning, Dr Karner exited the building and contacted an unknown party by mobile phone. Then, a minute later, you were at your window.”

“Oh, yes. I have been forgetting to close it. With so many longer days, it can be difficult to remember these things.”

“Your room was the only one to show signs of activity at that hour.”

“I was reviewing my notes from that day’s session. I heard a voice from outside, though not clearly. It was distracting me from my work, so I closed the window.”

“Do you commonly review your notes in the early hours of the morning with an unlocked window?”

“I just wanted some quiet. And I leave the windows open because otherwise I seem to find myself trapped with the smell of rotting flesh as well as humidity.”

Safin’s expression became easier to read, but not in a positive sense. This was not a man you wanted to be on opposing sides with. Madeleine kept the apprehension away from her face and her voice tightly controlled.

“Look. Without information about Dr Karner’s lifestyle outside MSF, I cannot give you an answer in good faith. I was assigned to survey him. He showed no signs of dereliction in his work, and to my knowledge kept his personal views separate from his duties. Whatever he said to me during outside hours was assumed to be in confidence. Many people say things to one another in what they believe to be confidence that they would not admit to otherwise. If I had reason to suspect he was unfit to work, I would have contacted the Medical Advisor privately.”

Safin held her gaze. She did not dare avert her face. Then he said: “The project coordinator is waiting for you downstairs. Thank you for your time.”

The rest of the day she spent in a different wing of the hospital. The Psychosocial Team was cut down from four members to three. Another inconsequential day of thankless work that never seemed quite good enough. That night Madeleine laid back on her bed and watched the shadows on the ceiling stretch over peeling paint, slowly overtaken by daybreak.

When she’d first arrived at the airport she could stave off her doubts with shallow, private reassurances. As long as you are here, you are just Dr Swann the psychologist consultant. Your father is many miles away and he won’t contact you. No one else of importance will come for you in a place like this.

With a guy like Safin around, she was safer than she would have been with the FSPs alone.

Safer, but no longer invisible.

#fanfic#fanfiction#upcoming projects#no time to die#technically this takes place a year after skyfall though#madeleine swann#lyutsifer safin#slow build#crime drama#still can't believe he's actually named lucifer and I have to work with this... somehow#at least he isn't named nacho that would be unsalvagable#the part of karner will be played by uh... gene hackmann I guess?#been thinking about The Conversation man what a nice film#good ost too

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#10yrsago The Photographer: gripping graphic memoir about doctors in Soviet Afghanistan, accompanied by brilliant photos

FirstSecond, one of the great literary comics presses of the modern world, has topped itself with The Photographer: Into war-torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders, a collaboration between photographer Didier Lefevre, graphic novelist Emmanuel Guibert, and designer Frederic Lemercier.

The book is the memoir of Didier, a photographer who accompanied a caravan of Medecins Sans Frontiers doctors into war-torn Afghanistan to staff a clinic in the middle of the Soviet-Mujahideen war. Didier dictated the memoir to Guibert (the graphic novelist who also produced Alan's War, a stunning memoir of post-war France) before he died of a heart-attack, and Guibert and Lemercier worked to turn this into The Photographer.

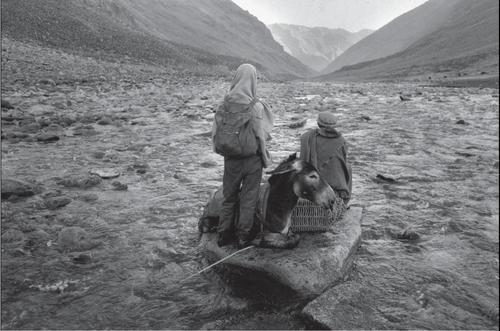

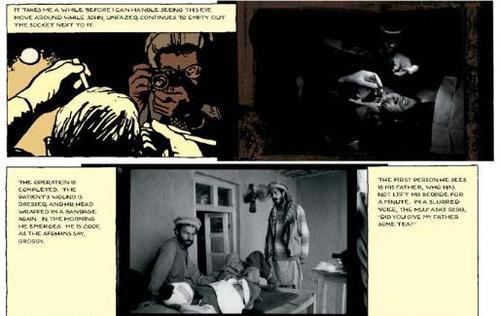

Visually, The Photographer resembles nothing so much as a Tin Tin adventure, except that it is liberally sprinkled with Didier's photos and contact sheets, dropped in among the drawn panels, incorporated seamlessly into the action. Didier was a powerful, naturalistic photographer, unflinching and unpretentious, and between the finished drawings and the annotated contact sheets, you get a sense of a real artist at work.

The story is in three parts: first, there is the journey to the clinic, which begins in Pakistan where Didier meets all manner of intelligence operatives, pathological liars, adventurers and NGO workers, and then follows the MSF crew as they meet up with escort of Mujahideen guerrillas and arms-smugglers, buy their horses and donkeys, and are smuggled over the border into Afghanistan. After this, the caravan proceeds through the towns and mountains of Afghanistan, dodging Soviet helicopters, losing pack animals over sheer cliffs, and watching in horror as the discipline in their escort is brutally enforced. The caravan is led by an unlikely and charismatic woman doctor who commands the Muj's respect through sheer competence and force of will.

The second part of the story tells of Didier's time at the clinic, as all manner of war-wounded, ill and orphaned victims are processed and treated by the doctors, tales of horrific woundings and incredible bravery and sacrifice and nobility. After a while, it becomes too much for Didier, who decides -- unwisely -- to return to Pakistan alone, with just an escort of Afghani farmers with whom he does not share a common language.

Finally, Didier tells the story of his voyage home, a gruelling trip that gets worse after he is abandoned by his escort. After coming close to death, he is rescued by grifters who rob him -- but get him to safety. After more misadventures, he arrives home, finally, in Paris.

The story is very well told, a gripping adventure that sheds light on subjects as diverse as faith, photography, art, love, nobility, Soviet-Afghani relations, pride, masculinity, racism, and bravery. As I said, the photos are magnificent -- worth the cover-price alone -- but the story makes them so much better. This isn't just a great photography book, it's a great novel, a great comic, a great memoir, and a great history text.

The Photographer: Into war-torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders

The Photographer sampler (PDF)

https://boingboing.net/2009/05/12/the-photographer-gri.html

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lesvos

I've been procrastinating writing this blogpost for a long time because it's felt like I'd have too many thoughts to effectively capture on paper and that it would be too rambling. But it's about time now, during my last evening in Mytilini, while my housemates cook food for my farewell dinner/party tonight before I leave tomorrow, that I get to it.

Mytilini and Moria.

I was so looking forward to this trip for such a long time. I was determined to keep a journal while I was here, to document the things I saw, the people I interacted with, to bear witness to the events. However, it was a perfect storm of circumstances that have forced me to have to leave for the States two weeks early. Before I arrived on the island, we knew of the Golden Dawn and other fascist groups holding rallies in the city of Mytilini and on the road to Moria, but then Turkey opened its borders and things got worse. The school at the One Happy Family community center, where my organization, Medical Volunteers International, operates a refugee medical clinic, was burnt to the ground by suspected fascist activities. This paused MVIs activities out of the clinic, and as fascist rallies started becoming more frequent, with some even attacking NGO workers and breaking car windows, there was an exodus of volunteers at the same time as Greece started tightening restrictions on NGO activities and migrant/refugee processing. They even suspended their cooperation under international asylum laws, rejecting new arrivals. A fascist group physically forced one refugee boat back into the water as they made land, resulting in the drowning of a child onboard. Then COVID-19 becomes a serious threat. There is one confirmed case on Lesvos, being treated at Mytilini hospital, but no known cases elsewhere. NGO activity is further hamstrung, and the local government makes no effort to facilitate aid to people trapped in the camp.

Fascists, fires, a pandemic, a volunteer exodus, restrictions on NGO activities. I've been frustrated at not being able to do anything about it all, despite being here. I know I could be more effective once I'm done with school, but even MSF and Kitrinos, two of the bigger medical NGOs still operating, have had to scale back their work. It feels like I came all this way to try to make a difference, and aside from about a week's worth of seeing patients, I wasn't able to do anymore. At times this has felt more like a poorly planned vacation than a trip to help people.

I also noticed that I wasn't as phased by much of Moria's situation: the open sewers, the poor hygiene, the burning of plastic for fuel, the rampant scabies, the five families living in one tent together, because it all felt very familiar. Like any slum I've visited in India. We are rightfully enraged about the EUs treatment of the refugees, and the conditions they've been forced to stay in. Perhaps justifiably more so because the EU has significantly better developed infrastructure and more money than does a country like India. But it made me consider why circumstances I get angry about here don't provoke as strong a response in my back home. Why do I more readily accept the status quo in India? I had this thought in a different vein a few years ago when I realized I treated service workers differently in India than in the States. Not that I treated them badly or dismissively here, but that in the States, be it due to a more common language or a less internalized sense of class structure, I found I'd treat service workers like people like me who are working a job. Potential friends, whom I treated as true equals in the sense of actually engaging and invested conversation. Whereas in India, I realized I never extended the same idea of possibly being friends to those who worked there. It was always cursory pleasantries, but never with the underlying idea that this person is a "real" person just like me, with a life outside work.

Perhaps it's just silly or privileged or stupid to have been thinking this way. Perhaps it's normal to think this way, as we can't be friends with everyone we meet and so we draw up those invisible divisions to make our social lives more feasible. Either way, the discrepancy between my thoughts/actions in the States vs in India was noteworthy to me, and one I have been conscious of not propagating further.

People.

Aside from that overarching frustration and general cloud over my thoughts however, the people I coordinated to room with are fantastic. As are the others I've met here. The house I'm staying in houses me, a German/French medical student, a German nurse, an Italian junior doctor, and a Spanish Antifa activist, and the landlord is a Syrian refugee who arrived on the island four years ago.

The translators we work with who become fast friends quite quickly include a Palestinian, a Burundian, and a man from Burkina Faso, the latter two of whom speak predominantly French, forcing me to improve my French significantly, having entire conversations for entire evenings in an entirely different language.

Then there are the coordinators of the different NGOs here. There's a German retired GP who made the decision to extend his trip in light of all the changes because he knows that now the need is highest and it feels wrong to leave. His family understands and supports his decision. There's an Irish lady who works with unaccompanied minors, i.e. kids below the age of 18 who have lost or been separated from their parents, aunts, uncles, or any family at all, but have somehow managed to cross an ocean to get away from the people literally destroying their homes. She teaches them, cares for them (sometimes as simply as giving them a place to shower), and more recently put one in touch with a lawyer to delay his deportation due to turning 18 and therefore being able to be tried as an adult. A 17yo kid, running away from the Taliban in Afghanistan, having had his family killed in front of him, arrives in Greece finally hoping he's safe, only to be deported to Turkey, where he knows and has no one. There's an American journalist who started an NGO to teach refugee kids to film and document their lives, giving them skills, and the ability to bear witness, but more so, just giving them something to do. He's stayed to document the EUs mismanagement of this refugee crisis. And there's a Russian teacher who runs a school for minors and children of refugees so they have somewhere to go and don't miss out on some form of education while their parents do what they need to to get by.

And lastly, I met the settled refugees in Greece, including my landlord from Syria and his friends. Got a haircut from one of his Iraqi friends, met some other friends of his in the Olive Grove, the overflow camp surrounding Moria.

The people I've met here are incredible. From all over the world, trying to do what they think is some good for the people they know are in need, in conditions where the vast majority of people would not stay in.

The remind me that everyone we interact with is just another human being, and force me to consider my own biases that I didn't realize I held until this trip. I didn't realize I unconsciously put up a guard around people who didn't speak the same language as me, or more accurately, people who didn't speak the same language, and, I'm ashamed to say, were doing poorly socioeconomically. Having traveled all my life and seeing the ends of the socioeconomic spectrum, I always thought I was very accepting and comfortable around any conditions. But be it a product of internalizing the presentation of certain types of people as dangerous or undesirable, or a core poor judgement on my part, I realized I was being defensive. It was clear to me when I was sitting across from this person on the bus, obviously living in Moria. I remember feeling an almost subconscious desire to avoid conversation. But then the Irish lady asked him if he was on his way to school, to which he excitedly replied yes, and showed her his notebook. I noticed it in myself again when we were surrounded by refugees as the Irish lady spoke to the boy about to be deported, and I found myself feeling uncomfortable, or even unsafe. But these were literally kids. 10 years younger than me, having seen and experienced so much more than I could imagine, gathering around to listen to how they could maybe help one of their newly acquired friends. I couldn't understand when I started feeling this way. I even jumped into a jog for a couple steps before very ashamedly catching myself when a homeless man in Atlanta tripped behind me.

What exactly am I scared of? Where is that insecurity coming from? And why, of all people, is it directed at those who are least fortunate? I hate that I've had to ask myself these questions. But I'm glad that I have. I think these questions are exactly those that many people in the world need to be asking themselves right now as well.

Life.

Living here has been a unique experience as well. Since my arrival, I knew my housemates were a special group of people. I've always only seen it on TV shows or in fiction, the idea of communal living, or a family of sorts formed out of the people you live with. Even in the States, my roommates and I very much kept to ourselves and led our own, parallel lives. But somehow, and perhaps because of the relative non-fancy-ness of our accommodation, that's exactly what happened with us. We would cook together every night and have dinner, go out for drinks with the other teams and organizations, spend afternoons together just talking. And the scaled-down lifestyle was something I was slowly getting used to as well. The relatively spartan bedroom with the creaky and drafty windows, the limited facility bathroom with the hot pipes running along the walls and the shower I can't stand up in, the "kitchen" with one working burner, knives more blunt than the spoons, and poorly draining sink, the laundry machine that no one knows how to work shorter than 5 hours, the cafe cat that started staying with us for food since the covid-19 lockdown, the tiny living room space that everyone gathers in both because it's the only option and because we're all new here and subconscously I'm sure want to spend time together with familiar faces. It's a simple life, with people you like around you, doing work you enjoy and find important. Life in Dayton with all the other things I normally do to try and fill my time seems so far away. I haven't watched a youtube video in two weeks, when I usually spend at least a couple hours watching back home. I've cooked more often these couple weeks with these blunt knives and poor kitchen than I did in Dayton over two months. I've learned new, inexpensive dishes. I've met and befriended more new people.

As my last post captured a snapshot of what I could see as my potential future, I think this trip captured a snapshot of what I think I wish my life could ultimately be like at least intermittently, if not always. When I do this kind of work that I already feel satisfied by, that feels important and fulfilling, I realize I don't feel that underlying insecurity or restlessness than makes me want to get involved in other things. I started Dayton Driven because I was too restless in medical school, for example. This feeling here reminds me of when I felt similarly in Geneva, just, finally, content.

I know there are other things important to me too though, in normal life, if not within this parentheses. I may not be able to be the Irish lady or American journalist, but perhaps I can be the German retired doctor, still being involved, still doing what I think is right, and still holding on to the other things important to me. Saara said something to me a couple months ago that I didn't realize would become something I'd think of quite often. She said, "If you ever feel like you are torn between two things and have to give up one, then you have the wrong two things." Maybe that's true. Maybe I can have and do every thing that I want. Maybe I can make it happen.

Well, it's at least pretty to thinks so.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cont. Travels of Cophine, Part 2.3

Tunisia.

Link for the entire work here: http://archiveofourown.org/works/13525500

They arrived in Sousse in the afternoon, their last stop in Tunisia and the end of their Francophone African experience. If everything went well here, they would be in Libya in a few days, and Egypt after that. Cosima's energy level was partially recovered and the sinus headaches were gone, but she still had frequent coughing fits, and her voice cracked every couple of words. She now spent her time propping up Delphine, who insisted that she wasn't really all that sick.

“Delphine, I love you,” Cosima said, “but your eyes haven't opened completely for, like, two days. Your voice is an octave lower, and your sneezes have woken the dead. You are fucking sick.”

Delphine fell back on her bed beside Cosima. In Tunis they'd gotten a queen sized bed in their room, which was great at first, but a lot less appealing when both of them tossed and turned the whole night. Here in Sousse, they were back to separate twins, and neither of them had the energy to even comment on it.

“Okay,” Delphine said, “I'm sick. Are you happy now?”

“No. I just want you to stop pretending that you're fine. I want you to take care of yourself. I mean, I'm happy taking care of you, but you're not letting me do that, and you're pushing yourself too hard.”

As if to prove Cosima's point, Delphine rolled over to check the little beep her phone just made. “Dr. N'Jikam wants to postpone our meeting until Wednesday.” She pinched the bridge of her nose.

“And you don't have to be at the clinic until Wednesday morning, either, so tomorrow we can focus on getting rest, yeah? Maybe check out that sauna they're supposed to have.” With the chilly weather outside and the lack of heat in the hotel room, spending the day at a nice 180 degrees fahrenheit had a certain appeal.

“Mmm... maybe. We still have a lot of arrangements to make.”

Cosima rubbed her back through her sweater. “We do. But we're not going to help anybody if you're not healthy. So you need to rest. That's what you told me the other day!”

“I can't sleep, I've told you.”

The night before, Delphine had apparently been awake for five hours while Cosima slept like a log. She'd drifted off for an hour or so on the ride into Sousse, but good sleep still aluded her. “Take some more NyQuil,” Cosima said. “Or I'll get the bar downstairs to make you a nice hot toddy.”

She shook her head. “Then I'll be hung over all morning. Is there any tea?”

Cosima checked the little complimentary beverage station near the ironing board. “Um... yes, but it all looks caffeinated.”

“Then no.”

Another coughing fit hit Cosima then, doubling her over as she pounded on her chest. The pounding never helped, but it was better than doing nothing. Once it subsided, she straightened back up and fumbled around for some more water. Delphine stayed on her bed, watching her.

“Have you tried the throat spray again?”

“Um, no.”

“Maybe you should. It would numb your throat and...”

“It would make me vomit again. No thanks.”

“You might've done it wrong.”

Naturally, Delphine was able to use the throat spray with no problems at all. Cosima added it to the list of things Delphine did effortlessly.

Cosima picked up her purse and wrapped her scarf around her neck again. “If I did, I'm not willing to risk doing it wrong again. But I will get some more cough syrup. And some more tea.”

Delphine propped herself up on her elbows to return Cosima's kiss. “Can you get some soup, too?”

“Yup. Soup, syrup, and tea. I'll be back soon, love.”

Delphine nodded and sank back down.

* * *

They tried the sauna the next day, but found it packed with Scandinavian women who all knew each other and laughed too loudly at everything each of them said. Cosima got some tea loaded with valerian root and lemon balm, and Delphine drank mug after mug of it while Cosima did their laundry in the hotel's facilities and brought containers of brik and fricassé from the vendors across the street. In the evening, they drank more tea and watched the Arabic dubbing of Downton Abbey on the hotel television.

On Wednesday it rained, the first time since they'd arrived in North Africa. Cosima sat at the bar in the hotel's restaurant and watched it fall in sheets over the cars and cyclists and old men in traditional burnouses hustling around with newspapers over their heads. It was just after noon, almost time for midday prayers, when the locals on the street would clear off for a moment but the tourists in the restaurant would stay. She knew these things now. She was also starting to forget that she hadn't always dropped the “h” sound in “hotel.”

The restaurant was packed. Most of these tourists were here for the promise of a sunny beach-side vacation in a relatively progressive Arab country, the lone gunman attack of a few years ago now a distant memory. The rain, however, put the beach off limits. The business men were here too, but in fewer numbers than in Tunis or Algiers. Cosima wondered how many tourists would be in Tripoli.

Delphine was supposed to be back by now. The clone here in Sousse had been easy to find, unlike the one in Tunis who'd gotten married and changed her name since the Leda List was compiled. Cosima double checked the time and confirmed that this clone's appointment had been for 10:30, and then she texted Delphine.

Everything okay?

While she waited for a reply, she scrolled through her Facebook feed, finding very little that was new since that morning. Alison posted pictures of a black forest cheesecake from all angles; Cosima's mother posted memes that she thought were hilarious and Cosima had seen ten years ago; Scott cracked science jokes; her father ranted about Republicans. Same old, same old. She thought about reading the news, but she'd done that earlier and had no desire to repeat the experience. She was nervous enough about going to Libya without reading that the country was “mired in chaos” and ruled by “men with guns.” She wanted to keep her worries confined to the language barrier.

“Anything else?” The bartender gestured to her empty tea cup.

“Yeah. Another one. Thank you. Merci. Shukraan (شكرا.)”

He gave her an indulgent smile and got her more hot water and some fresh tea.

Instagram yielded no new results, either. Five of the Ledas were hyper active there, posting so many photos of their personal lives that Cosima felt closer to them than to most of her own cousins at this point, and was becoming personally invested in the little drama that was brewing in the love life of one of the Austrian sisters. All total, Cosima tracked 33 Ledas through Instagram and 34 on Twitter, 11 of which were on both. None so far had symptoms of clone disease that they were sharing on social media, though the Leda in Cape Town, South Africa, did seem to have a worrying rash on her torso that had nothing to do with being a clone, but probably with a swimming in the ocean.

Her phone buzzed. Difficult patient. Delphine said.

Cosima arched an eyebrow. That could mean many things. And?

A reply wasn't immediately forthcoming, and Cosima rubbed her face to keep from swearing. The restaurant was loud enough that she might've gotten away with it, but it was better not to risk it, even surrounded by foreigners. She tried to look out the window but a man pushed up to the bar and blocked the view. He was tall and broad, wearing what Cosima called the “I yell at my family in public” uniform.

“Hey!” he shouted. “Can we get a table, please? We've been waiting fifteen minutes!”

Cosima rolled her eyes and went back to her phone. No reply from Delphine, but another cake picture from Alison on Facebook – red velvet this time.

She pulled up Twitter and perked up again. A clone from southern California they hadn't made contact with yet finally posted something. She was in Cambodia, it turned out, and she had a long thread about politics and southeast Asian history that was actually quite fascinating. And then Delphine replied to her text.

Still trying.

“Still trying? That doesn't help, Delphine.” She tapped out her response. Do you need anything? Can I help?

She'd been at the bar for over an hour. She could have been up in their room, working on her thesis, or napping, or masturbating, or catching up on her reading. But Delphine had asked her to be here, to meet her after her 10:30 appointment at the clinic, because she was bringing one of her contacts from MSF, and this was an Important Contact. Cosima was wearing her nice shirt, for fuck's sake, and she'd ironed her pants. They were going to eat lunch together, their treat for this Important Contact, so Cosima had not eaten since 8:30 that morning.

She typed some more. Do you have an ETA?

Three minutes later, as she watched the loud man yell at his son for touching the floral arrangement on the table they'd finally gotten, her phone buzzed. Her excitement faded when she saw it was just an email from her mother.

Cosima,

Here's that dress company I told you about, based out of the City, very social-justice and queer oriented and I think right up your alley. It's pricey but we'd be happy to help you out if....

She closed the message without finishing it. “I am not dress shopping online, goddamn it,” she muttered. “How many times do I have to f.... ugh. Mother.” She rubbed her face again and checked the time.

12:40 pm. Five minutes since her last message to Delphine, and more than two hours since the appointment at the clinic started.

A bearded man in a West Virginia University sweatshirt sat down beside her, apologized when he brushed against her knee, and placed his order with the bar tender in Arabic. Once the bartender left, he laced his fingers together and turned to Cosima. “Heckuva weather we're having, yeah?”

“Yup. Sure is.”

“You know, I been coming here for ten years, and I swear this is the first time I've seen it rain.”

“Hm.”

He tapped the bar top. “Are those dreads you've got?”

“Yes.”

“I thought so! They look good!” He turned a little on his stool to face her more. “Usually white girls can't pull those off, but yours look really good!”

“Thank you.” She checked her phone again. 12:45, and no new messages.

“Can I ask, if you don't mind, what you did to make 'em stay so well? Like, my cousin tried dreads, and she's as white as me, and her hair stank!” He laughed and bumped into her knee again. “Like, it was just straight up matted and shit. What's your secret?”

She drained her tea and looked him in the eye. “I've been genetically engineered.”

He chortled. “Okay. Fair enough. I shouldn't have asked; I'm sorry.”

Cosima raised her eyebrows and did not respond. The bartender came with his order then – a steaming bowl of stew with a side of bread and a bottle of beer. The stew smelled amazing, and she still hadn't gotten any messages from Delphine, so she called the bartender back over and ordered a bowl for herself. While she waited, the cups of tea crept up on her and she slid off to the ladies' room, leaving her coat on the stool, pockets empty.

While she peed, she texted Delphine again. Is everything okay over there?

The clinic was on the same block as their hotel, and Cosima would have gone there herself an hour ago if they weren't terrified of accidental clone meet ups.

She also finished her mother's email about that dress shop in San Fransisco, which, Sally was keen to point out, also did tailoring for suits. Great.

Back at the bar, Cosima's coat was still there, along with her food and a fresh cup of tea. The WVU man was wrapped up in conversation with a guy to his left, thankfully, and now there was a different customer to Cosima's right – a woman with short wavy black hair, wearing a collared white shirt. As she walked towards her own seat, Cosima glanced down at the woman's shoes. Sure enough, Keens, or Keens equivalents. Cosima's phone buzzed.

Yes was all Delphine had to say. No ETA, no other information. Cosima put her phone back in her purse.

“Excuse me,” she said as she squeezed in between the two other customers to sit down.

“Sure, no problem,” the woman said, smiling at her. The WVU man did not seem to notice her return. “I hope no one was sitting here?”

“Oh, no,” Cosima assured her. “You're fine.”

The soup was delicious, but spicier than she'd anticipated, so she got a glass of water and another serving of bread to help it go down. In minutes her sinuses opened up and she needed extra napkins, as well. The woman beside her got a salad and a glass of wine, and smiled at Cosima when she drained her water glass.

“A bit spicy, is it?” She was British, or Irish, judging by her accent.

Cosima nodded. The water helped, but her eyes watered and her nose ran, and it was a damn good thing she wasn't trying to look good right now. She thought of Delphine's MSF contact and checked her phone again. It was 1:10. No new messages. “Whatever.” She dropped it back in her purse and gave the rest of her soup her full attention. When she'd finished, she wiped the bowl with some more bread and finished her third glass of water. Beside her, the dark haired British woman watched her, sideways.

“I guess it was good,” the woman said.

“Yeah. Delicious.” She pointed to the half-full salad plate in front of her bar neighbor. “Yours wasn't?”

The other woman shrugged. “I keep forgetting that I don't like tomatoes. I order them every so often, thinking that some dish looks rather good, and then I eat one, and remember.”

Cosima smiled. “I'm like that with oysters and clams. Someone will rave about how good they are, and swear they've got a good recipe, but it's always like eating a snot ball out of a shell.”

The other woman laughed at that, throwing her head back and showing off her neck in the process. “That is such an apt way to put it! They really are nature's little snot balls, aren't they? Tell me, have you read Tipping the Velvet?”

If she hadn't suspected this woman was queer before, she sure did now. More than suspected. Cosima blushed a little and grinned. “I read it when I was, like, twenty. So yeah, but it's been a while.”

“Well, I've read it several times, and every single time, when she's going on and on about oysters and how she prepares them and all that, I just have to shake my head, because I find oysters absolutely disgusting, just as you do.”

“Are they better or worse than tomatoes?”

“Worse. A thousand times worse.” She picked around the tomatoes on her plate, eating pieces of cheese and lettuce speared on her fork. “If I may ask, what brings you to Tunisia?”

“Oh, it's a, uh, a medical trip, of sorts.”

“Hm, I see. Like, medical tourism sort of thing? I've heard of that, and you're American, I take it?”

“I am, yeah. No, it's not for me. I mean, I'm not getting treated for anything.” She twisted her napkin between her fingers, trying hard to look nonchalant.

“You're doing the treating, then, perhaps?”

“Something like that.”

“Cosima?”

She spun around to find Delphine three feet behind her, frowning. “Oh, hey! When did you get here?”

“I got here a few minutes ago, as I said in my message. Did you get my message?”

Cosima dug in her purse for her phone. “The last message I got just said...” She looked at her phone. Sure enough, two new messages from Delphine, at 1:12 and 1:20. It was now 1:27. “Shit.”

“You haven't reserved a table, then, I take it.”

“They wouldn't let me unless I could give a more specific time!”

“Well, if you'd checked your messages, you would have had one. But now we have to wait.” She gestured over to the hostess stand, where a West African man in a linen suit waved and headed in their direction through the other diners. “He has a busy schedule, you know. He is a doing us a favor.”

Cosima gathered her coat and purse. The bartender had their room number to charge for the meal, thankfully. Fussing over credit card payments wouldn't improve either of their moods. “I do know that, and actually, Delphine, I've been checking my messages all day, and you weren't sending any, so maybe you should lay off a little bit?”

It was not the right thing to say, and it was not the right time to say it, but it came out of Cosima's mouth anyway. Delphine's eyebrows went up. She glanced over at the woman to Cosima's right, who was smart enough to pretend she wasn't listening. “Well,” Delphine said, “at least you made a new friend.”

The man in the linen suit reached them and gave Cosima a broad smile.

“Dr. N'Jikam,” Delphine said, “this is Cosima Niehaus, my research partner.”

“Pleasure to meet you, Miss Niehaus. Dr. Simplice N'Jikam, from Médecins Sans Frontières. Dr. Cormier and I used to work together. Perhaps she's mentioned me.”

She put her best smile on for him and shook his hand. “Yes, she has. It's a pleasure to meet you, too.”

As dramatic as Delphine was about waiting for a table, they only had to wait five minutes to get one. Cosima sat across from Delphine, with Dr. N'Jikam to her left. Predictably, Cosima wasn't very hungry any more, but she ordered a carrot salad with hard boiled eggs and another cup of tea. Delphine ordered a lamb platter with couscous and vegetables. She must not have eaten since that morning, either. At least she seemed healthier than she had the day before.

Dr. N'Jikam started off the conversation as soon as they'd ordered. “So, you are going to Yemen.”

Delphine nodded. “That's correct.”

“When do you plan to be there, and for how long?”

“We're not sure exactly,” Cosima said. “It depends on how successful we are there. Right now, we have five days scheduled in early March, but that could change.”

The waiter brought their drinks – water for Delphine, coffee for Dr. N'Jikam, and mint tea for Cosima.

“And what exactly,” Dr. N'Jikam asked Delphine, “is your measure of success for this trip? What is your objective?”

“We've identified three women with a specific phenotype that puts them at risk for a terminal condition, and we plan to inoculate them against it, or cure them if they've already developed symptoms.”

His eyebrows rose. “What condition is that?”

“It's only recently been discovered, so there's not an agreed-upon name for it yet.”

“I see. And you've already identified patients already? How?”

“It's a long story. Some of our connections back in Canada gave us the information.”

The answer satisfied him, and he sipped on his coffee. For Cosima, though, the effects of her earlier bowl of soup and all the accompanying water became pressing, so she excused herself, meeting Delphine's “wtf” look with a wide eyes. Whatever. It would be worse to sit there bouncing and in pain, unable to focus. Waiting in line for the ladies room for the second time, she rummaged in her purse for her bottle of TUMS, and took two.

Back at the table, the food had once again arrived in her absence. Squeezed onto the table between the plates, glasses, silverware, decorative flower arrangement, and complimentary flatbread, Dr. N'Jikam had his tablet and a pad of line-free paper, which he and Delphine crouched over between bites. Delphine glanced at her when she sat down, and continued her conversation with Dr. N'Jikam in French.

Cosima ate her salad and listened, picking out about half of what Delphine said and less than a quarter of what Dr. N'Jikam said. She'd read that Cameroonian French was a little different than Canadian or Parisian French, but she hadn't expected such a great difference. But then, Delphine wasn't having any such difficulties. From what Cosima understood, they talked about the Yemeni refugee crisis, camps, transportation options, and money, and then Dr. N'Jikam said something that made Delphine laugh. Cosima raised her eyebrows at her, hoping for a translation, but none came.

At the end of the meal, Delphine excused herself to use the restroom, letting Cosima handle paying for the meal.

“How was it?” she asked Dr. N'Jikam.

“Pardon? Oh, it was excellent,” he said. He dabbed at his lips with the napkin and smiled at her. “Thank you.”

“You're very welcome,” Cosima said. The food and the rain made her sleepy, but she needed to keep up appearances. “So, uh, how long have you been with MSF?”

“A long time. Twenty years, almost. And I've been, oh, I've been everywhere.” He laughed at that, so she smiled along. “But we've been talking the whole time, and you've said very little. Tell me, Miss Nyehouse, is it Nyehouse or Neuhaus? I can't remember.”

“Uh, Niehaus, actually, but that's not important.”

“It's important to me.” Another grin. “So tell me, Miss Niehaus, how long are you working for Dr. Cormier?”

“Well, I've been working with her for about three years now.”

“Three years, okay. I've known her for almost five years, since right after her doctorate. I wasn't aware before that she had any students.”

“She doesn't.”

He paused, hand midair on its way to adjust his glasses. “No? I thought that...”

“Wait, did she tell you that I'm her student?”

Dr. N'Jikam did not miss the way Cosima leaned over the table as she spoke, and he leaned back to compensate. “Oh,” he laughed, “I don't remember! You know, as we age, ours minds are not so good.”

“Right. Okay.”

He left as soon as Delphine got back, shaking their hands again and repeating his best wishes and his pleasure at having met them both. Delphine promised to keep in touch throughout their travels.

At the elevators, Cosima told Delphine, “You know, if you didn't need me to be there, you could have just said so.”

Delphine rolled her head around on her shoulders. “What are you talking about?”

“You know I understood like, less than half of that entire conversation. You made it pretty obvious you didn't need my contribution.”

Delphine sighed and rubbed the bridge of her nose. An elevator at the end of the row dinged, and they hustled to get on it along with a gaggle of rain soaked tourists. They flattened themselves against the back wall. “He prefers speaking in French,” Delphine said.

“Does he really. English didn't seem to be much an issue for him when we first sat down, or after you'd gone to the bathroom.”

The elevator stopped to let some people off at the third floor, and replace them with a Japanese couple in bath robes, fresh from the third floor sauna. Cosima could have been at the sauna during that entire lunch, and it wouldn't have mattered. Whatever.

“How about our patient?” she asked. “You said she was difficult.”

“She refused the vaccination. Nothing I said, nothing her doctor said, convinced her, and she left without it. After talking my ears off about every medical problem she's ever had, and how doctors are responsible for every single one of them.”

“Oh sh... shoot, really?” That had never happened before. Usually, once the doctor explained it, the patient accepted the vaccine. The trick was often just getting them into the doctor's office to begin with.

“Really. She claims that vaccines made her infertile.”

The elevator stopped at the eighth floor and let out everyone else, then moved on up to the tenth, where Cosima and Delphine got off.

“The doctor is trying to bring her back the day after tomorrow,” Delphine said. “If she still refuses, though...”

“She won't. We'll think of something.” Cosima reached for her arm, but Delphine moved away to unlocked the door and push it open.

Inside the room, Delphine set up her papers on her bed, and sat in the armchair next to it with her laptop. “Dr. N'Jikam sent us both a list of other contacts we should talk to. Some are in Libya, which he doesn't know as much about, but cautions us against visiting.”

Cosima opened her laptop on the desk. She had had other ideas for the afternoon, especially since it seemed they'd be staying in Sousse longer than originally planned. Delphine was buried in her work, though, chewing on a thumbnail, so Cosima might as well follow suit.

“Great. Sounds like a perfect afternoon.”

* * *

That night, after pouring over Dr. N'Jikam's information, calling and emailing his contacts in Yemen, Libya, and a Jordanian refugee camp, and a last minute phone call with one of Art's Arabic translators, the walls of their little hotel room were pressing in against both of them. Cosima's eyes hurt from differentiating tiny Arabic words from other tiny Arabic words and staring at screens, but there was one more email to write.

Dear Dr. Lacrabére,

I was directed to you by Dr. Simplice N'Jikam of Médecins Sans Frontières because

“It goes the other way.”

“Huh?”

Delphine stood behind her, one hand in her damp hair. “It's Dr. Lacrabère, not Lacrabére. You need the accent grave, not aigu.”

“Oh. Shit. Thank you.”

Delphine walked on towards their suitcase and said, “It's not Spanish.”

“Yeah, I'm aware of that, thanks.” She finished the email, watching Delphine's eyebrows do that sarcastic little wiggle in her peripheral vision. “By the way, did you tell Dr. N'Jikam that I'm your student?”

“What?”

“He thought I was your student. Like, your graduate student or something.”

Delphine dug around her suitcase for a bottle of lotion. “I don't know why. I introduced you as my research partner. You were there when I introduced you, yes?”

“Well, yeah, but...”

“But what?”

“I dunno. It was just weird, that's all.”

“Okay.” She sat on the edge of her bed and rubbed lotion into feet. “You should take your shower now, so you're not up too late. I'm going to talk to the doctor at the clinic again tomorrow.”

Cosima refrained from replying with “yes, Dr. Cormier,” but she got up and gathered her shower things. At the bathroom door she turned back and saw Delphine massaging lotion into her left calf, her eyes closed.

The hotel bathroom was nice, with a bathtub and strong water pressure from the shower head. She let the water beat against her back, her head bowed. When she got out of the shower later, Delphine would probably be in bed. A different bed, because of course no one could know they were lovers, so they had separate twin beds. Again. Delphine's eyes would be covered, and she'd be turned away from Cosima because the light was on Cosima's side of the room. She would not want to talk, either about important topics or trivial ones. And then she would get up early in the morning to try convincing their sister here in Sousse that she needed a vaccine. And Cosima would.... what?

Maybe she'd stay in tomorrow. The forecast called for more rain, after all. She could work on her dissertation, enter more data and run some preliminary stats on them. She could go back to the restaurant and drink a couple more gallons of mint tea. She could stay in bed all day, and it wouldn't make much of a difference.

She turned off the shower and leaned against the tile wall. How long would it take for Delphine to wonder what she was doing in here, or what was taking her so long? Or was Delphine still so annoyed with her that she was happy to have Cosima out of the bedroom for a while?

The steam from the shower swirling around her, she slid down in the bathtub, her face in her hands. Tears pushed out of her eyes before she could stop them, and then she was sobbing.

A minute or so later, the door opened, and Cosima took some deep breaths to try to gain some control, hands still over her face.

“Cosima? Hey, hey, hey....” And then Delphine's hands were on her neck, and her arm was around her shoulders. “Shh... come here.”

She leaned onto Delphine's shoulder and cried some more, soaking her T-shirt and clinging to her arms with wet fingers. “I'm sorry,” she managed. “I'm sorry.”

“For what?”

“For not seeing your messages, for not knowing French better, for not helping you cure the Ledas, for everything.”

Delphine stroked her arms and her back and kissed her head. “Chérie, it's okay. I don't expect you to know French very well, and you cannot help me with the Ledas any more than you already are. You know that. You already do so much for them, anyway. And the thing with the messages was just a mistake, a misunderstanding. It's okay.”

“It didn't seem that okay earlier.”

Delphine's chest rose and fell as she sighed. “I was just... irritated earlier. That's all. I'm sorry I took it out on you.”

Cosima held on to her, nose in the crook of her neck. Delphine had some new jasmine-scented body wash that smelled okay, but didn't smell like Delphine. Cosima wanted her to smell liked Delphine again, goddammit. “I love you,” she whispered.

“I know. Je t'aime aussi.” She kissed her eyes, her lips, and the tip of her nose. “We should get you out of this tub, though.”

“Yeah, this isn't very comfortable.” She let Delphine help her out of the tub and into a towel. “Are you still mad at me?”

“No,” Delphine said. “I was, but I'm not anymore.”

She nodded. “Yeah, I was a little bit pissed at you, too.”

“Are you still?”

She shook her head and finished drying herself off. “No, not anymore. I... I can see why you were upset. I should've just kept my phone out the whole time so I'd see your messages, and...”

Delphine folded the towel in half and hung it up on the rod next to hers. “Maybe. I don't think I would've been quite so upset with you if you hadn't been talking to that girl, though, if we're being completely honest.”

“That girl?” Cosima smiled now as she pulled on her shorts. “She's, like, our age or older.”

“Oh? Is she?”

There was an edge in Delphine's voice, so Cosima put her hands on Delphine's waist. “I didn't ask, and she didn't tell me. There is nothing for you to worry about. I'm engaged to you, and nobody else.” She kissed her, but pulled back after a moment. “I mean, we are still engaged, aren't we?”

Delphine's laugh turned into a cough. “Yes, we are still engaged! Just because we can't tell everyone doesn't change that fact. Now come on, let's go to bed.”

Cosima tucked herself into bed and watched Delphine tweeze her eyebrows with the help of a pocket mirror. Delphine did that most nights, and some mornings, sometimes also yanking hairs from her nostrils in ways that made Cosima's eyes water just watching her do it. “What would your eyebrows look like if you didn't do that?” she asked.

“Euhh... let's not find out, okay?” She got one more hair from her left eyebrow and closed the mirror, then turned off the overhead light and sat on the edge of Cosima's bed, looking down at her. “I want to stay attractive for you as long as possible.”

“Yeah, same here. I mean, for myself. For you.” She wasn't terribly attractive at the moment, of course, but she wasn't going to bring that up.

Delphine rubbed Cosima's abdomen through the blankets. “I'm sorry the beds are so small.”

“It's not your fault. And it's not forever. Here.” She scooted all the way to one side and pulled the blanket back. “You can climb in for a minute if you want.”

“A minute.” Delphine stretched herself out under the heavy blankets and faced Cosima. “I think we're both very tired.”

“Yeah, and you're still sick, even if you're moving around better.” She linked her fingers with Delphine's. “I don't want you to think that I don't appreciate everything you do. For us, I mean. For all of us.”

Delphine kissed her eyes, damp again with tears. “I don't think that. I know that you do.”

“Good.”

“And I don't do any of it by myself. I couldn't do any of it by myself, and I would never want to.”

Cosima thought of Delphine earlier that day, spending hours trying to convince a clone that she had a condition that would kill her one day. “Do you want me to go to the clinic with you? To try convincing our skeptical Tunisian sister?”

Delphine gave an amused little huff. “I would like that very much, but I'm not sure it's a good idea.”

“Right. Probably not.” She tucked herself as close to Delphine as possible, angling her face so that Delphine wasn't breathing directly into her eyes. Delphine wiggled her arm so she could hold Cosima's hand between their faces.

“Of course she's allowed to refuse, but I have some ideas that might convince her.”

“Ideas that don't involve clone disclosure.”

“Of course.”

“Are we still doing our five day rule if she keeps refusing?”

Delphine groaned. “No. I think, if she refuses a second time, we let her refuse, and we move on. She'll have our information, we'll have hers, and we can always come back. I am not arguing with her for five days.”

“Fair enough. That sounds like a plan, then. We really do need to come up with a decent name for this disease, though. Maybe not tonight, but some time before we've cured everybody.”

“I've been thinking of one, actually. I thought of it today, when Inès was questioning everything I said.”

“Yeah?” Cosima propped herself up a few inches. “Can I hear it?”

“I was thinking we could call it Fitzsimmon's Carcinoma.”

Cosima remembered the chipper swim coach whose body had taught them so much about what their disease was and the ways that it couldn't be treated, and she smiled. “I like it.”

“I hoped you would.” She pulled Cosima closer and snuggled against her body. “I didn't want to name it without your permission.”

“Well, you have my enthusiastic permission to use it. I'll tell the sestras tomorrow.” She yawned into Delphine's chest and kissed her her collarbone. “Je t'aime,” she whispered.

Delphine giggled. “I love you, too. Very much.”

And with one hand tucked into Delphine's, and the fingers on her other hand hooked on the waist of Delphine's shorts, Cosima drifted off to sleep.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/fighting-ebola-is-hard-but-in-the-congo-mistrust-is-making-it-harder/

Fighting Ebola is hard but in the Congo mistrust is making it harder

As the disease latched onto families and spread through tightly packed neighborhoods, rumors began spreading of organ harvesting and political conspiracies, even as more people got sick and died.

When the ambulances came to take people away – they would never see them again.

So instead of going for treatment, many stayed at home and died, their bodies still highly contagious and deadly for the family members who buried them.

“Fear prevents good management of the epidemic. Fear makes it difficult to break the chain of transmission. What was needed was to break the fear,” says Zongwe.

It’s this extreme mistrust, along with simmering conflict and what many responders on the ground believe has been a flawed response, that has allowed the world’s second-biggest Ebola outbreak on record to continue unabated more than 10 months after the first cases were found.

Despite millions of dollars in funding, and an effective experimental vaccine, Ebola is spreading to new parts of Congo’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces and re-infecting areas thought rid of the virus. This month, it also made the long-feared jump across the border to neighboring Uganda, though at this stage those isolated cases appear to be contained.

A conflict the world forgets

Butembo’s residents live at the frontier of a conflict that the world often forgets.

Hemmed in by multiple armed groups that commit repeated atrocities and harassed by the national military frequently accused of human rights abuses, they are famously and understandably distrustful of newcomers.

Earlier this year, unknown assailants destroyed Ebola treatment centers in Butembo. In April, a World Health Organization epidemiologist was killed in an attack on the University Hospital. In total there have been 130 attacks on health facilities between January and mid-May, causing four deaths and injuring 38.

Because of these security concerns, the White House barred world-renowned specialists of the US-based Centers for Disease Control from setting up a base in the heart of the epidemic (although it does have staff based in the regional capital Goma.) Similarly, Doctors Without Borders (Medecins Sans Frontieres) closed its treatment centers in some Ebola-hit areas and retreated to Goma.

Faced with an epidemic that is out of control and continued violence targeted at the response, health authorities are urgently searching for a different strategy to stop Ebola.

“During the first seven months of the epidemic we had more than 1,000 cases, now we have more than more than two thousand cases in a very short time,” says Antoine Gauge, a response specialist with Doctor’s Without Borders (MSF).

A draft internal World Bank assessment on the response from late May seen by CNN, describes the mounting shock at the rising death toll.

“Alarmed by the huge and unexpected surge in recent months in the number of new cases, a number of aid agencies and implementing partners have expressed concerns over many aspects of the response,” it reads.

It describes a response top heavy on operational costs like salaries and hazard pay. More than half of the budget for WHO’s strategic response plan during that period was allotted to staff remuneration. At the same time, it also shows that WHO was 40 million dollars short of its requested funding.

“We are absolutely outraged about how this response is going,” one senior humanitarian official based in North Kivu told CNN, saying that WHO would be better served by letting more nimble expert teams, that cost far less, do the work. The official refused to be named, citing fear of criticism from the WHO.

Christian Lindmeier, a spokesman for WHO, says the organization is committed to the people of the DRC affected by the disease and that every key aspect of the response was labor-intensive.

“As some partners and NGOs have had to leave due to insecurity or other reasons, WHO has stepped in and absorbed their tasks,” he said in an emailed statement.

“We owe a great deal of gratitude to the 700 brave WHO personnel who, working in partnership with the DRC Ministry of Health and hundreds of their national health workers, ensure that the response continues to operate across all vital functions, particularly when support is not immediately available from others.”

Community care

Alima, the French NGO, believes it has found a solution to the mistrust that has stopped people seeking treatment. It’s both hidden and in plain sight. Perched half-way up a hillside next to a school, their Ebola reception center is right inside a local clinic in the heart of the community.

A thermometer and a quick consult separates incoming suspected Ebola cases from other patients.

Community members were brought in and consulted at the beginning of the construction.

There are no alarming Ebola warning signs and posters. It just looks like part of the existing clinic. And that was the point: It’s not a scary place, hidden away. It’s in the community, as part of a system that treats all ailments.

“As soon as we fixed our approach, the results were there,” says Zongwe.

But to the frustration of Alima, it is the only reception center of its kind in Butembo. Plans to build more have stalled. And, while innovative, it isn’t nearly enough to stem the spread.

“This potentially could’ve been controlled earlier in the outbreak, when it was in a rural area, but letting it go fester underground with unknown chance of transmission, has really prolonged it, and we need to make sure we do everything we can to stamp it out now,” says Dr. Ben Dahl, a leader of the CDC response based in Goma.

Innovation in treatment means if Ebola victims are identified quickly and get to treatment centers from reception centers, hospitals, or clinics, they have a much better chance of surviving.

To make treatment easier and less intimidating, Alima has developed what they call “the cube.” Separated by a thin layer of transparent plastic, patients are able to interact more directly with doctors — they can talk to family members who visit. All of it is an attempt to reduce the fear of Ebola and convince people to come in.

Major reset

During and after the devastating Ebola outbreak that spanned several countries in West Africa from 2014 to 2016 and killed more than 11,000, the WHO faced scathing criticism for acting too slowly and warning the world too late.

In response, the global health agency reorganized its emergency response structure and strengthened its operations.

But in this outbreak, at least according to the responders we spoke with on the frontlines of treating Ebola, it hasn’t worked as planned.

David Gressly, freshly appointed by the UN as an Ebola Tsar of sorts, says the Ebola emergency response has gone through a major reset in recent weeks in the wake of internal criticism and a mounting death toll.

“If the virus continues to circulate, it remains a constant threat to spread to other provinces in this country and to neighboring countries and one day it will if we don’t find a way to bring it to a halt,” says Gressly, who previously managed the region’s UN peacekeeping operations.

CDC’s Dahl says that the existence of the vaccine, which while experimental has been found to be 97% effective in the Congo, has led to complacency and the legwork of tracing patient contacts and quickly isolating them has not been done thoroughly.

“We were very fortunate to have this vaccine. It has probably reduced some of the cases and without it, we would have a much larger number of cases,” he says.

“But they have not been doing the public health fundamentals of quickly following all the contacts, listing all the contacts, and isolating them as soon as it becomes symptomatic,” he says.

He says around half of cases are still unknown to the contact lists and a large number of positive cases are deaths in the communities — from people who wouldn’t trust or couldn’t get to early treatment.

Contact lists allow epidemiologists to ring-fence an outbreak. When a positive case of Ebola is identified, the victim is interviewed to find out who they were in contact with. All of those people get on a list and, in an effective outbreak response, they are closely monitored.

To get this outbreak under control, the CDC says more than 70% of cases need to seek treatment early and upwards of 80% of cases need to be on the contact lists. Otherwise, it will continue to spread.

Beaten up and stoned for taking temperatures

Samuel Mutahwa was unemployed when the virus hit Butembo, but when the outbreak hit he volunteered to help. Now he plays a critical detective role of tracing contacts that could help break transmission.

Armed only with a thermometer, he leads his contact tracing teams through the neighborhoods of Butembo. Twice a day for 21 days — the maximum amount of time from time of infection to onset of symptoms — they follow up with their list of patient contacts.

Mutahwa entered the compound of a grandmother and grandson that visited a sick friend in hospital. The friend later died.

“36.8 — she is fine,” says Mutahwa, holding a thermometer up to the smiling woman.

But earning the trust of his own community has been a hard fought and dangerous process. In the early months, Mutahwa says that he was beaten up and stoned.

“They said they were going to kill me. But I said no, I know what I am doing. I have to save the life of my people,” he says.

Survivors part of the solution

Ebola is an intimate disease that is highly contagious but only contracted through direct contact.

It attacks families and then spreads through communities — often through so-called “super-spreaders” the 20% of cases that spread the disease to 80% of the people.

It is often the personal choices of Ebola victims that can have an outsized impact on the transmission chain.

When the sister of Roger Mumbere Wasukundi, 17, got sick earlier this year, he says nobody wanted to believe that she had Ebola. They didn’t even believe that Ebola existed.

After they buried his sister, his aunt got sick and quickly died. Roger, his mother, and his father all contracted the virus. Only Roger and his mother survived.

“I was sent to the treatment center because I didn’t want to give up. They told me I could survive and I believed them. Everyone prayed for me,” he says, sitting in his classroom in Butembo.

He still dreams of being a lawyer, but the virus still affects his health, his eyes clouded by the after effects of Ebola.

He believes that survivors like him can help turn the tide in the fight against Ebola and dispel the mistrust that has made the disease so hard to beat.

“Ebola survivors (need to) go talk to communities. Because this epidemic is very real,” he says.

Source link

#current health news usa#Fighting Ebola is hard but in the Congo mistrust is making it harder - CNN#Health#healthcare news usa#us public health news#Health News

0 notes

Photo

Out of Character:

Name/Alias: Arda.

Pronouns: She/her/hers.

Age: 25.

Timezone: EST.

Face Claim Preferences: Charlie Hunnam.

Character Basics:

Full Name: Gabriel Mason.

Nicknames/Prefers: Gabe.

Age: 37.

Occupation: Trauma Surgeon~ Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders.

Gender: Male.

Hometown: Hartford, CT.

Current Neighborhood: Cohen Point.

Highest Education: MD, PHD.

Religion: None.

Family and Relationships:

Parents: John and Marie Oliver.

Siblings: Three adoptive sibling sisters~ Jade, Nia, Bobbi.

Children: Alexander Ramos (Gabriel is unaware that the child is his at this point).

Other: Deceased child.

Pets: No pets.

Sexual Orientation: DemiSexual.

Romantic Orientation:Heteroromantic.

Marital Status: Divorced.

Personality:

Favorite Film: The Godfather.

Favorite TV Show: The Sopranos.

Favorite Book: The Dark Tower.

Favorite Song: Stairway To Heaven.

Favorite Color: none.

Likes: Chess,runology, Linguistics, Ice Cream, Netflix.

Dislikes: Liars, disloyalty, liver, avocadoes, birds, cats.

History:

Gabriel’s life began in an incubator, according to his adoptive parents. He remained there for six months after his birth. He had been born prematurely due to his mother’s heroin abuse. A side effect of which was his own opiate addiction. After testing positive for opiates at birth, Child and Family Services stepped in. He then became a ward of the state. According to his parents, his birth mother only remained in the picture a short time. She came to visit him in the hospital the first week of his life but disappeared not long after. She would later die from a heroin overdose and his father was never identified. John and Marie Oliver stepped in as foster parents, raising him from birth. They would later adopt him. He had been lucky. John and Marie were kind, generous people with a strong faith. John was a doctor and Marie an attorney. They were the adoptive parents of four children. Gabriel was the oldest of his adoptive siblings, three sisters.

Gabriel was three when his adoptive parents realized he had a ferocious appetite for reading and a photographic memory. By the time he was three years old, Gabriel was speaking four languages fluently. The traditional school system proved to be inadequate in their efforts to keep Gabriel challenged, thus his parents began to homeschool him with the aid of tutors from the third grade on. For all intents and purposes, Gabriel was considered a child prodigy, having an above average IQ and mastered all the required testing for each of his respective grade levels. His parents fought tooth and nail against their son being escalated through any grade levels beyond his age. When Gabriel finally began high school, his parents agreed to allow him to simultaneously complete undergraduate coursework at a community college. By the time he graduated high school he had an exceptional GPA, and dozens upon dozens of scholarship offers to attend practically any school of choice.