#amy clampitt

Text

It’s Fine Press Friday!

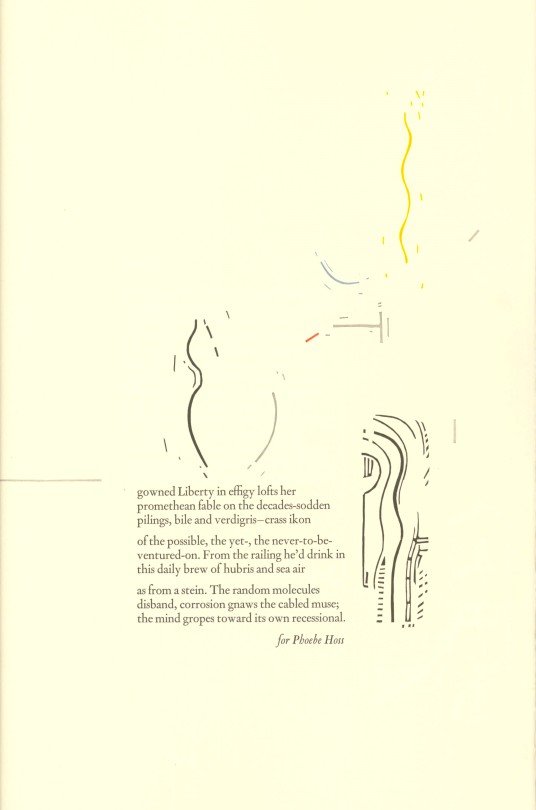

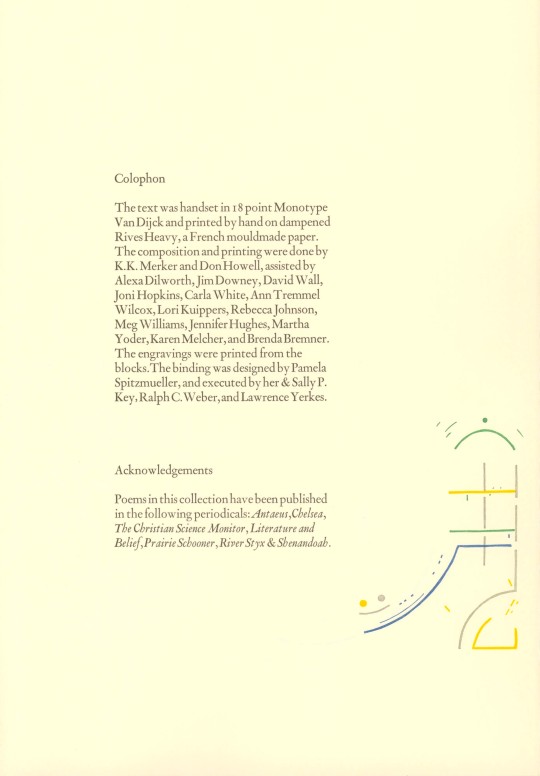

Today’s fine press book is another from the collection of our late friend Dennis Bayuzick, entitled Manhattan. The book consists of poems by Amy Clampitt (1920-1994) with wood engravings by Margaret Sunday. Each poem references varying observations and places in Manhattan, accompanied by woodcuts created by Sunday. At first glance, these engravings seem simply to be abstracted lines, but it becomes obvious that they are illustrations of the surroundings in Clampitt's poems. Subway maps, construction equipment, and housing can all be seen in Sunday’s woodcuts.

Manhattan was printed by Kim Merker and Don Howell for the University of Iowa Center for the Book in an edition of 130 copies on Rives Heavy mouldmade paper. The type is handset 18pt Monotype Van Dijck. Poems were previously published in a variety of periodicals including Antaeus, Chelsea, and the Christian Scientist Monitor.

View other books from the collection of Dennis Bayuzick.

View more Fine Press Friday Posts.

– Sarah S., Special Collections Graduate Intern

#Fine Press Friday#fine press fridays#Dennis Bayuzick#Amy Clampitt#Manhattan#Margaret Sunday#Kim Merker#Don Howell#University of Iowa#University of Iowa Center for the Book#wood engravings#van dijk type#rives#poetry#New York#fine press printing#fine press books#fine press publishing#Sarah S.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Athena

Amy Clampitt

Force of reason, who shut up the shrill

foul Furies in the dungeon of the Parthenon,

led whimpering to the cave they live in still,

beneath the rock your city foundered on:

who, equivocating, taught revenge to sing

(or seem to, or be about to) a kindlier tune:

mind that can make a scheme of anything—

a game, a grid, a system, a mere folder

in the universal file drawer: uncompromising

mediatrix, virgin married to the welfare

of the body politic: deific contradiction,

warbonnet-wearing olive-bearer, author

of the law’s delays, you who as talisman

and totem still wear the aegis, baleful

with Medusa’s scowl (though shrunken

and self-mummified, a Gorgon still): cool

guarantor of the averted look, the guide

of Perseus, who killed and could not kill

the thing he’d hounded to its source, the dread

thing-in-itself none can elude, whose counter-

feit we halfway hanker for: aware (gone mad

with clarity) we have invented all you stand for,

though we despise the artifice—a space to savour

horror, to pre-enact our own undoing in—

living, we stare into the mirror of the Gorgon.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

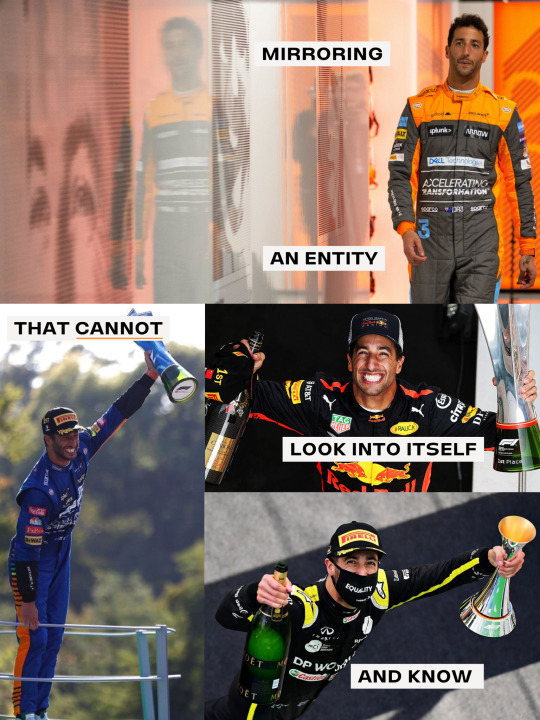

daniel ricciardo x a procession at candlemas

#daniel ricciardo#dr03#web weaving#amy clampitt#web#mine#i spent an obscene amount of time on this#red bull racing#q#w#words

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

[...] moving lights along Route 80, at nightfall,

in falling snow, the stillness and the sorrow

of things moving back to where they came from.

Amy Clampitt, final lines from A procession at Candlemass

see here

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nothing Stays Put.

Nothing says put. The world is a wheel.

All that we know, that we're

made of, is motion.

— Amy Clampitt, from "Nothing Stays Put" from Westward (Alfred A. Knopf, April 7, 1990)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Vague fancies

of Aeolian harpings, twined with weird oaks'

murmurings."

----Amy Clampitt

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

…the branches overhead so full of small, unfrightened quicknesses…

— from “Notes on the State of Virginia”, Amy Clampitt (source)

I just love the use of “quicknesses” as a name for small birds (warblers?)

#Notes on the State of Virginia#Amy Clampitt#poetry#writing#literature#poets on tumblr#quotes#excerpts#birds#warblers

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Clampitt, Amy. “Amy Clampitt, The Art of Poetry No. 45.” Interview by Robert E. Hosmer. The Paris Review, Issue 126, Spring 1993.

[Text ID: “There were a lot of relative, a lot of cousins, and at Christmas there would usually be a huge family gathering—pleasant in a way, yet I remember being miserable. I couldn’t deal with all the people who sounded so sure of themselves when I didn’t feel sure of anything.” /end ID]

#amy clampitt#the paris review#casually getting my ass handed to me this morning#I GET IT AMY I GET ITTTTTT#wowowowow#quotes#*

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dancers Exercising

Frame within frame, the evolving conversation

is dancelike, as though two could play

at improvising snowflakes’

six-feather-vaned evanescence,

no two ever alike. All process

and no arrival: the happier we are,

the less there is for memory to take hold of,

or—memory being so largely a predilection

for the exceptional—come to a halt

in front of. But finding, one evening

(cont.)

on a street not quite familiar,

inside a gated

November-sodden garden, a building

of uncertain provenance,

peering into whose vestibule we were

arrested—a frame within a frame,

a lozenge of impeccable clarity—

by the reflection, no, not

of our two selves, but of

dancers exercising in a mirror,

at the center

of that clarity, what we saw

was not stillness

but movement: the perfection

of memory consisting, it would seem,

in the never-to-be-completed.

We saw them mirroring themselves,

never guessing the vestibule

that defined them, frame within frame,

contained two other mirrors.

0 notes

Text

The Sun Underfoot Among the Sundews by Amy Clampitt

0 notes

Audio

In Nothing Stays Put: The Life and Poetry of Amy Clampitt, Willard Spiegelman explores the highly unconventional path and mindset of this Iowa-born, late-blooming talent, who lived for much of her adult life in a small studio apartment in the Village and, after years of failing as a novelist, published her first collection, The Kingfisher, when she was sixty-two years old. She became an instant star in the field of American poetry; she died only eleven years later, leaving us with five beautiful books. A poet of long sentences and ornate, flowing music, Clampitt did not confide her secrets directly in her verse; the biography provides a kind of subterranean poetic map of her life. Of this energetic presence, a woman who wore vintage hats and scarves with flair, Spiegelman observes, “Amy knew how to live ‘poor,’ but she also knew, perhaps as compensation, how to write ‘rich.’” In the passage below, the poet immerses herself in studying Greek.

. . .

As Clampitt was assembling what would become The Kingfisher, she did something she had long promised herself she would do. It was, in part, a much-delayed homage to her father, the Grinnell Classics major who had first taught her the Greek alphabet. Having studied Greek literature in translation, in school and college, and having finally visited Greece in 1965, she enrolled in Ancient Greek language classes. As early as 1954 she had written about wanting to read Sophocles in a bilingual edition, making use of a newly purchased secondhand Greek dictionary. A decade later, on board ship en route to Greece, she took daily half-hour classes to learn basic conversational phrases. Her intellectual curiosity was, as usual, excited by anything having to do with language, whether native or foreign, contemporary or dead.

She got up the courage—as she had four years earlier when she enrolled in Daniel Gabriel’s workshop—to sign on for a weekly class in Attic Greek at The New School in the fall of 1981. She was sixty-one. She took her inspiration from the journalist I. F. Stone, who started his Greek studies at seventy-one in order to learn about Athenian democracy from Thucydides, in the original language. Her classmates ranged from curious young people to a retired physician who read with a magnifying glass. It was the kind of variegated community that had always appealed to Amy, this time in a classroom rather than in a bus or at a protest meeting. “Thrilling though formidably difficult,” the course was grist for an intellectual’s mental mill, with short selections from Pindar, Aeschylus, Simonides, and the Gospels circulating among the students every Saturday from nine in the morning until one in the afternoon, under the watchful eye of Sam Seigle, a moonlighting professor from Sarah Lawrence, whom Amy adored. He “has the learning and the imagination to bring the entire scene alive, and almost every minute he is striking flint with some new insight, historical or etymological.” The material was manna for the voracious student.

Interviewed forty years later, Seigle remembered his student vividly. Coming from the avant-garde precincts of Sarah Lawrence, the professor taught without a syllabus, encouraging students in an elementary course to devise their own paths through new material in a strange tongue. They were forced to think for themselves, he said, especially about the nature of the words and phrases they were learning. “Always curious,” he said, Amy took to “the precision of syntax, and the exactitude of the language” with her typical intellectual alertness. She thrilled, her professor recalled, to the difference between an objective and a subjective genitive (e.g., the two meanings of “the love of God”), a concept she had previously not known. After the semester ended, Seigle never saw her again. Nor did he forget her.

The following semester, Amy stayed uptown, at Hunter College, within walking distance of home on East 65th Street. Here she read Homer with Irving Kizner. She described this to Vendler as “one of the great experiences of my life.” And to Salter she recounted the mouthwatering thrill of those famous, ringing and untranslatable Homeric phrases like “polyphlosboio thalasses” (“the much-sounding sea”) whose sound is integral to the meaning, regardless how you translate it. She found “it impossible to convey the peculiar excitement that goes with all this: it’s like arriving in a place you’d dreamed of all your life.”

When she was young, Amy had dreamed of Manhattan, of England, of Greece. She landed, successively, in all of them. She had dreamed, too, of the Greek language, and now was immersing herself in it. She landed in Greek as well as Greece. She traveled both in the flesh and in her mind. One lovely result was a Petrarchan sonnet—“Homer, A. D. 1982”—that appeared in What the Light Was Like. It begins with a nod to young John Keats’s first great poem, “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” which conveys the excitement available to both real-life travelers and stay-at-home explorers who experience an original only vicariously, like Keats reading Homer in translation: “Much have I travelled in the realms of gold, / And many goodly states and kingdoms seen.” Amy was a traveler of both sorts. Clampitt’s 1982 Manhattan is like, and unlike, Keats’s 1816 London.

Here is the octave of her sonnet, dedicated to Kizner:

Much having traveled in the funkier realms of Ac-

ademe, aboard a grungy elevator car,

deus ex machina reversed, to this ninth floor

classroom, its windows grimy, where the noise of traffic,

πολυφλοίσβοιο-θαλάσσηζ-like, is chronic,

we’ve seen since February the stupendous candor

of the Iliad pour in, and for an hour and a

quarter at the core the great pulse was dactylic.

An attentive reader can hear the poet mingling the dactylic rhythms (DUM-da-da) of Homer with the insistent iambs (da-DUM) of English, and alternating in her rhymes between the hard, consonantal endings in lines 1, 4, 5, and 8 and the more mellifluous, liquid sounds of lines 2, 3, 6, and 7. The “great pulse” is a throbbing, bilingual one, Homer’s and Clampitt’s together. This poem projects the energetic fun that a polyglot intellectual can have, and can share with her readers.

. .

More on this book and author:

Learn more about Nothing Stays Put by Willard Spiegelman.

Learn more about Amy Clampitt and browse other books by her.

Hear Willard Spiegelman read from Nothing Stays Put at Grinnell College in Iowa, on Friday, April 21 (no registration required) and hear his featured guest appearance on the Close Readings podcast with Kamran Javadizadeh.

Visit our Tumblr to peruse poems, audio recordings, and broadsides in the Knopf poem-a-day series.

To share the poem-a-day experience with friends, pass along this link.

#Spiegelmanaudio#poetry#knopfpoetry#knopf poetry#poem#amy clampitt#biography#willard spiegelman#national poetry month#excerpt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Athena

Amy Clampitt

Force of reason, who shut up the shrill

foul Furies in the dungeon of the Parthenon,

led whimpering to the cave they live in still,

beneath the rock your city foundered on:

who, equivocating, taught revenge to sing

(or seem to, or be about to) a kindlier tune:

mind that can make a scheme of anything—

a game, a grid, a system, a mere folder

in the universal file drawer: uncompromising

mediatrix, virgin married to the welfare

of the body politic: deific contradiction,

warbonnet-wearing olive-bearer, author

of the law’s delays, you who as talisman

and totem still wear the aegis, baleful

with Medusa’s scowl (though shrunken

and self-mummified, a Gorgon still): cool

guarantor of the averted look, the guide

of Perseus, who killed and could not kill

the thing he’d hounded to its source, the dread

thing-in-itself none can elude, whose counter-

feit we halfway hanker for: aware (gone mad

with clarity) we have invented all you stand for,

though we despise the artifice—a space to savour

horror, to pre-enact our own undoing in—

living, we stare into the mirror of the Gorgon.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wanted: Penpals

I am a published poet looking for one or more penpals to trade messages with about poetry, day-to-day life, and shared interests. My passions are poetry, modern literature, world cultures, history, art, cinema/art films, theater, classical and folk music, architecture, historical fashion, and vintage transportation. I am also willing to discuss things I am less knowledgable in like ancient culture and history; philosophy; crafting, bookbinding, etc. I am not geeky and am not interested in video games, Marvel/DC, or TV shows. I'm not interested in Classical or Medieval literature. I hate high fantasy and sci-fi. I hate horror and romance genres. I am not in any fandoms. I don't like Tarot, Astrology, or Taylor Swift.

My favorite movies include Brief Encounter, Russian Ark, Tarkovsky's Mirror and Andrei Rublev, Kurosawa's Ran and Dreams, Days of Heaven, and The Lion in Winter. My favorite poets include Ruth Stone, Ellen Bryant Voigt, Amy Clampitt, Natalie Diaz, and Ocean Vuong. My favorite books are Inland by Téa Obreht and Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishnan.

I am 31 years old, male, and gay, and seeking someone who is at least 21 years old, and preferably at least 24, and emotionally mature. I am looking to trade long-form emails on a monthly or semi-monthly basis, once every two to four weeks, on an agreed-upon and fairly regular schedule (this can be discussed later). I am also open to chatting informally on a more frequent basis, such as every few days. I love hearing from people about the things they study! I also love hearing about life in other countries, for those who aren’t from the US.

I require anyone I correspond with to support LGBT rights, and support Palestine.

I welcome both people who are knowledgeable about poetry and people who aren't knowledgable but want to learn more. I have a lot of PDFS of poetry books I can share.

Several of my poems have recently been professionally published! You can read a few here:

https://www.youngravensliteraryreview.org/yr19-sean-eaton.html https://eunoiareview.wordpress.com/2024/02/28/my-grandfather/ https://arborealmag.com/issues/04-fresh-hell/sean-eaton-poetry/ https://apricitymagazine.com/portfolio/the-boxer/ https://apricitymagazine.com/portfolio/sea-lions/

I am a friendly, intelligent, caring, earnest person, so please give me a try if any of this sounds at all interesting.

No men (cis or trans)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sun Underfoot Among the Sundews

But the sun

underfoot is so dazzling

down there among the sundews,

there is so much light

in the cup that, looking,

you start to fall upward.

— Amy Clampitt, from "The Sun Underfoot Among the Sundews" (The New Yorker, August 14, 1978)

4 notes

·

View notes