#amatonormativity anecdotal

Text

Honestly I probably wouldn't find Taylor Swift nearly so annoying if it weren't for a large contingent of her fans thinking she's hotter shit than what Satan last shat.

#anecdotes by peachdoxie#like sorry! but i don't buy the 'authenticity' that so many of her fans claim she embodies#she's an artist with a good marketing team who found a certain kind of song to sing as her brand#then there's the other issues of 1) the amatonormativity of her music#and 2) the whole private jet thing#also no taylor swift is not a queer icon fuck off with that bullshit#actually that's probably the most annoying part#is people reading their own ideas onto taylor swift's brand and content#when that reading is pulled out of their ass based on asinine wishful thinking#its the same issue i have with people who do it to movies and tv shows and books as well#learn some basic media literacy for fucks sake

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Does anyone else ever think about how amatonormativity makes it such a paradox to be aroace? When you don't have a committed relationship partner, you're expected to be the most emotionally/financially/socially free and available, when in fact you're so exhausted from having to prioritize yourself (due to not having a partner to help provide for you) that you actually have less of the aforementioned resources available to you than anyone you know who is in a partnered relationship.

Like, yeah, in an ideal world, you'd get support from your platonic relationships to alleviate this, but amatonormativity is just so pervasive that, in reality, this is exceedingly rare, to the point that the only scenarios I've even heard of in which someone holds their non-romantic/non-sexual relationships at an equal or higher priority (generally speaking) than their romantic/sexual relationships are like. Two anecdotes I read on Tumblr in the entire 10+ years I've been here.

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see a lot of sad confessions here so here's a slightly happier aro/ace anecdote.

I identified as aroace for all of my teenage years; at 20, I realized I was transmasc, and at 21 I started experiencing romantic attraction.

I have a qpp. He's been my best friend since I was 7. I never gave much thought to my orientation, but I came out as aroace shortly after he did (even back then I had a sneaking suspicion that I might have been demi or gray, but stuck with the aroace label because I didn't intend to act on it, regardless of whether or not I felt it).

I identify now as alloace, I'm pretty sure I experience romantic attraction towards him, and we're queerplatonic partners. We have a dog. We have our own apartment. I have many more ace- and aro- spec friends online, and have met a few more besides my partner and myself in school as well. No one tries to force amatonormativity onto me, and I'm starting to embrace my feelings of attraction as well (in a way that I still don't intend to act on, as I'm very happy with my current partnership setup).

I draw. I just got into a graduate school (which I'm a little scared of, but excited for). I'm hoping to pursue a career in research (feels like an autistic ace stereotype a little bit but that's ok). I've slowly let myself drift away from friends that made me feel ashamed of myself and towards friends that will be excited with me and communicate with me and give me the benefit of the doubt when I slip up or say something wrong.

I've found a pretty happy place to settle in for the rest of my life, I think, and I expect that this little social home I've carved out will continue to grow as I do.

#aromantic#asexual#aroace#arospec#acespec#aspec#aroacespec#arose#trans#transgender#nonbinary#non binary#non-binary#nb#enby#transmasculine#transmasc#ftm#trans guy#trans man#transgender man#transgender guy#queer platonic partner#queer platonic relationship#qpp#qpr#squish#friends#friendship#alloace

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

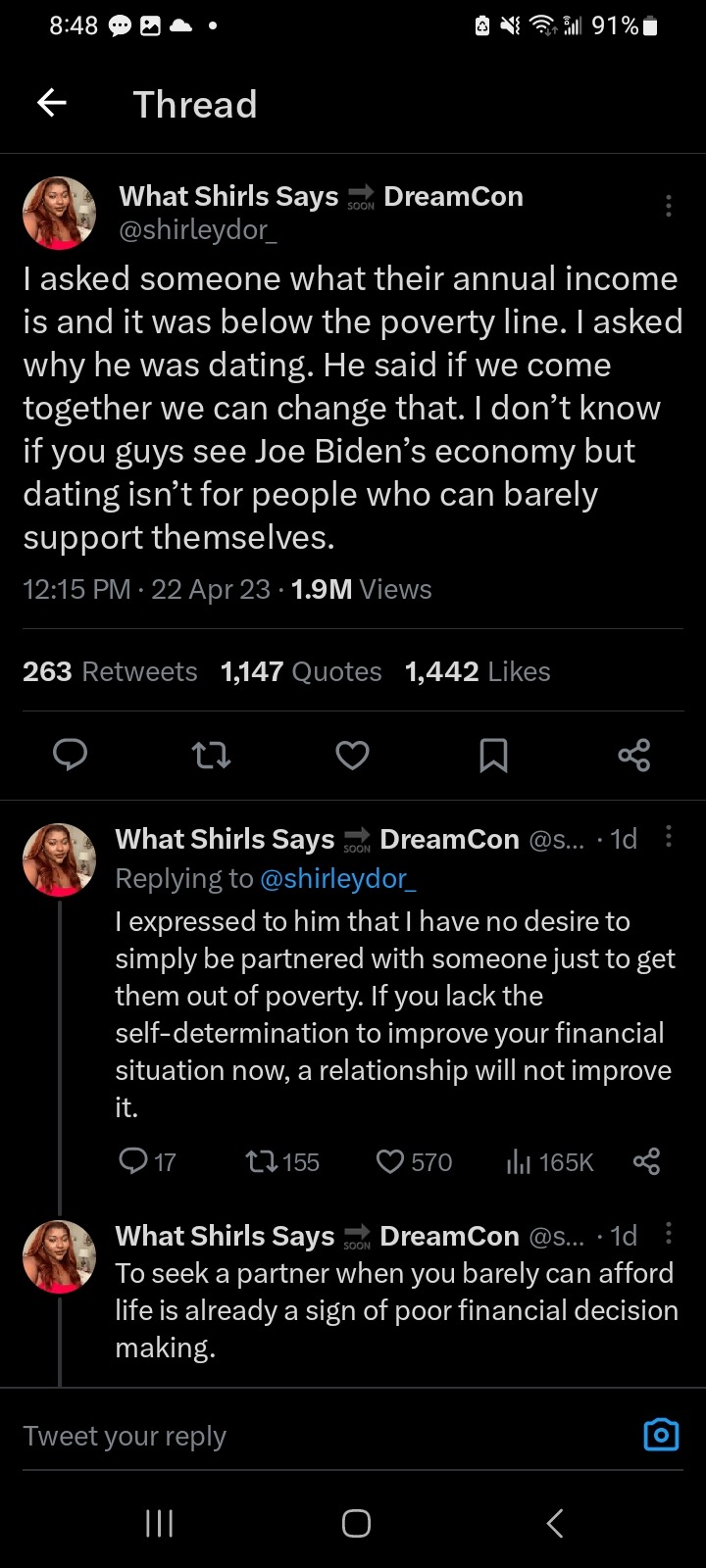

I need to move this from my "to read" list to my "have read" list (like over 50 other damn things) but this tweet had me thinking about the coining of amatonormativity again, which was done in Minimizing Marriage: Marriage, Morality, and the Law by Elizabeth Brake.

I realize tumblr is brain poisoned as fuck about this still, given that I believe I saw a post calling amatonormativity "rape apologia" as recently as 2020, but part of why this tweet is fucking stupid is that being in a relationship is smart economic sense, has been for a very long time, and Minimizing Marriage actually... discusses this.

Even living together without papers is economically beneficial. Rent is priced above a third of a lot of people's income. Two people's income, however... and of course, we're all familiar with the "getting married for tax benefits" joke. The only people for whom it's not economically beneficial to have a partner/be married in Biden's economy are the disabled, because the law specifically punishes you if you're on benefits for being married, because of eugenics.

Marriage itself is in large part a matter of finances. You're creating a unit which has joint finances, and historically your family would benefit economically from marrying off their kids (dowries/dowers/bride prices, and not needing to provide for as many people, and I'll note here that this is still true of many families today).

To underscore this: I recently saw an anecdote that this is part of why child marriage occurs in the US and Canada. Now, I did not see this person link academic or journalistic discussion about this aspect specifically, but I'm inclined to believe it.

The flip side of this tweet as well is that the OP is basically saying "the less you live the more you can work, and some people do not deserve to live" like it's a good thing, and someone replied to her stating that sentiment even more clearly, which immediately brought to mind this quote by Marx- "The less you eat, drink, buy books, go to the theatre or to balls, or to the pub, and the less you think, love, theorize, sing, paint, fence, etc., the more you will be able to save and the greater will become your treasure which neither moth nor rust will corrupt—your capital. The less you are, the less you express your life, the more you have, the greater is your alienated life and the greater is the saving of your alienated being." This sentiment compounds with the fact that discouraging the poor (who often overlap with the disabled, the racialized lessers, the queer, etc) from having relationships, families, and/or children, is again, part of eugenics.

#Cipher talk#amatonormativity#The fight for marriage is and was a fight for economic equality (disabled people still haven't won that right in the US)#The fight against marriage and the family and a dozen other things related to this is the fight to destroy these kinds of economic#Pressures and bonds that necessarily exclude people from having full status and full protection in society#Socially and economically#Not to destroy family or committed relationships but to destroy the bludgeoning they can be used for in presence or absence

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Went through your comic tag again because I needed a pick me up and your anecdotes always makes me smile. Very cute and infinitely charming (and it reminds me to tone down the amatonormativity for my ace bff oop)

Thank you so much for the kind words TwT I've said it before but I'm really struggling with my self-confidence as a comic artist, especially on stuff that isn't fan-art, so I'm always super grateful for comments like these TwT

Thank you so much for being mindful, too <3

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

if anyone has good articles/books/video essays/anecdotes/anything to share on amatonormativity or aromanticism (or asexuality, but that's more tangential to my interests) please send them my way! doing an informal lit review

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cut the crap, Hamlet! My biological clock is ticking, and I want babies NOW! (Elogium, s2e4)

I get the sense that "Elogium" is an episode that viewers find embarrassing. Maybe I am just projecting my adolescent feelings onto the internet consensus. It is certainly somewhat hamfisted, but it also belongs to a genre that we might call "reproductive health body horror" and, like... I'm kind of into it?

The premise of the episode is, of course, that space alien radiation causes Kes to enter estrus. (Unaccountably the Ocampan word for this is "elogium," which is a real Latin word for something else. Okay guys!)

Let's get the "bad science fiction watch" out of the way: Ocampan reproduction makes no sense from a population biology point of view. If an Ocampan couple can only reproduce once, they need to have a multiple pregnancy to maintain population levels, not the single child Neelix seems to be contemplating. (Also, having kiddos at age five means that grandparents would often not be around to participate in elogium rituals, as the Ocampan lifespan is 9.)

Additionally, it's hard to know what to make of the revelation that Kes hasn't reached "puberty" yet. The show seems to be decoupling intellectual/emotional maturity from reproductive capacity, but we are left with some very awkward questions about Kes's relationship with Neelix. Like, sex aside, what does romance mean for a young Ocampa? This show doesn't dare ask the question, such is its fragile allo/amatonormativity.

Still, I thought Jennifer Lien's performance was strong - emotional and a little weird while still respecting her character's personhood. In an important scene (one that frames her relationship with the Doctor as a parent/child one, thank god), she questions whether she wants a kid and makes a self-affirming decision that I loved to see, though I wish it had been dramatized more fully.

And, like, occasionally, having a uterus does make you feel like you're in a dirt-eating fever dream. I don't know if the alien physiology metaphor will work for everyone but I sorta dug it.

Neelix is, of course, trash in this episode, with the return of his jealousy subplot, his dreadful gender essentialism, and the extremely cliched portrayal of him as a reluctant father. His "should I be a dad" dilemma is fundamentally relatable, but instead of showing a real dialogue between a couple that's been avoiding the question, he and Kes start the episode with gender normative beliefs (she wants a baby, he wants adventure) and switch positions after some extremely light self-reflection. They're never on the same page, and they don't make the decision together.

On a happier note, this one's shippy! The episode starts with Janeway and Chakotay having one of their ridiculous whisper-conversations on the bridge. People are (shock!) hooking up and they need to decide what to do about it. This is very weird and silly because both Starfleet and the Maquis seem cool with fraternization, and they're 70,000 light years from home. Surely there is not even a conversation to be had, other than a need for some policies and mental health supports around breakups? But we do get Chakotay asking his extremely impertinent question about Janeway's personal dating plans, and the introduction of the Janeway chastity vow.

It makes sense for Janeway not to date crewmembers, especially in light of her commitment to Mark (this episode was originally slated for season one). But what about Chakotay? He is also everyone's boss?? I think that even in the 23rd century people should still not date their bosses, but this show does not seem to know this and it bums me out, particularly because of the gendered double-standard here.

(Mollie watch: Janeway is looking at a Mark/Mollie photo in the final scene. The show wants us to believe she's pining for her man, but honestly I think the baby talk is just making her miss her doggo. In my head canon Janeway is the type of person who responds to all child-rearing anecdotes with stories about her dog.)

Ensign Wildman, and her pregnancy, are also introduced, and we get another J & C scene where Janeway affirms the crew's right to have kids (hashtag reproductive justice) and contemplates the possibility of becoming a generation ship (whoa, slow down, lady! Like, of all the ethical questions about having kids while space marooned, assuming they'll continue your mission for you is quite a leap!)

Tuvok's line "It appears we have lost our sex appeal, Captain," sums this one up: despite all the innuendo, this is a very unsexy episode, and I think that's by design. Family planning is often unsexy! I just wish it had gotten a little closer to contemplating the real issues that emerge from our dual natures as people with bodies and people with agency over those bodies, and the push and pull of figuring out what that means for us, individually and in relationship.

3/5 bowls of mashed potatoes with butter (a Terran delicacy!)

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey! Hope you are doing well

I was wondering if I could get a reading about my romantic soulmate, any information you can share with me would be greatly appreciated

I’m A, she/her 🐧🫶🏻

Thank you so much in advance

MMMMMMMMMMMMMM, gurl I'm gonna be real with you.

Much as how Saint Valentine and Christmas have a cute, full of love root of origin (and quite a lot of catholicism in the mix) but rn are a costume for capitalism in the worst of cases, Romantic Soulmates are a disaster.

Soulmates don't exist

🚨🚨🚨 AROMANTIC TAROT READER ALERT 🚨🚨🚨 (ajshashas)

I'm sorry pal, but it's true ahshas. The notion that you're "soul bounded" to just ONE single human in this world isn't true.

Almost all of us want to feel romantically loved and looking for your "half orange" is an honest desire. But the thing with "soulmates" is that you're chaining yourself to this specific person and closing the door to your heart freedom for no good reason.

And that is in the best scenario, in the worst, there are many many anecdotes about people in very toxic relationships that were trapped by thinking "this person IS my soulmate, I CAN'T be with anyone else" and that is DANGEROUS as fuck.

Don't put mind chains on yourself, pls. You deserve more.

And this applies to the "Future Spouse" thing too, I'd love to answer, but I can't promote this kind of thought. Nothing personal, it's not you, it's the amatonormativity that impregnates our society to the bone hahsas.

#divination#tarot#cartomancy#witchcraft#fortune telling#tarot cards#witchblr#tarotblr#aromantic#aro#romantic soulmates#soulmates#future spouse#love reading

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

an aspec goes to a bookshop

I recently had my first encounter with an aroace Sci-Fi in Japanese and just had to write about it.

I enter a bookshop and feel like crying. I don’t know which book to pick up and I end up spending more time walking around than reading. This has been typical of me in a bookshop over the past few years, since I started to identify as aspec.

Growing up, I’ve always been a bookworm. As soon as I learned to read, I started devouring all the books I could get my hands on. Recently I found a reading diary we were made to keep in primary school, and the small notebook contained the titles of many more books than I had remembered. Fantasy had already become my favourite genre. I probably read so many books during that time that I didn’t remember what happened in each story.

Looking back, I can’t pinpoint when that started to change. As I got older my reading skills developed and I came to digest each story more slowly and carefully so I could enjoy the reading experience. That explains why I became so bad at deciding what to read; when you want to take time for it, you would want to choose what you enjoy reading.

But that wasn’t the only reason, though I couldn’t figure it out at first, and maybe it already started in the fifth or sixth grade. As I grew older, the books recommended for my age group started to contain elements of romance, a certain kind of interaction between a girl and a boy (it was always a girl and a boy - which I didn’t care that much at that time because being anything other than straight simply wasn’t given as an option anyway). I still enjoyed the books and got excited about all the adventures and characters and emotions and all that was there, and I read the romance plots just as any other kind of b-plots. But then, romance and sex became more and more dominant with time, both in books I read and in conversations I had with my friends. I started to feel as if I were much younger than them, too “innocent” and childish for those topics. It might also have had something to do with the fact that Asians are often perceived as younger than their age in Western/European contexts, which was often the case where I spent the latter half of my teenage years, but that definitely wasn’t the only reason. When I came across the terms asexual and aromantic, things started to make so much sense.

But as it might be the case for many, figuring out at least part of my sexuality wasn't necessarily the most difficult part, unlike many of the YA books I had previously read about queer experiences. Just as much as I was relieved to have a way to describe myself and to find others whose experiences and feelings I share, I also came to notice small and big things built upon the premise of heteronormativity and amatonormativity, and how other people seem to smoothly navigate through them, and be hurt by those little things like advertisements on the metro and anecdotes in daily conversations. It might sound like an exaggeration, but it did feel that way. Little things like that often build up.

For me, one of the ways in which the impact manifested was that I started to sometimes feel like crying in bookshops and libraries, my favourite places of all. I felt like I was out of place in those storyworlds. I became scared of picking them up.

I don’t mean to say that all (hetero) alloromantic allosexual people enjoy all the books in the world. But there are simply more options to choose from to relate to in any genre. Of course, there are a vast number of stories and books and every person can like or dislike them, relate to or not relate to them; it’s not unique to queer, aspec, or aroace people. But objectively speaking, there are many more books built upon the premise that romantic and sexual relationships and interactions are an essential and natural part of anyone’s course of life. At least the stories I’ve encountered have been that way, especially those supposedly for “grown-ups” that I found in bookshops in Japan. And when the sheer existence of that premise in a book felt like rejection and exclusion, just the idea that none of the books in the bookshelves went directly against or weren't based on that premise made me want to cry. I started to avoid stopping by the fiction shelves. And that’s been the default for the past few years since the very striking discovery that not everyone feels the way I do and that I was rather the odd one out that the descriptor aroace can be applied to. I got used to feeling as if there were no books for me to read without feeling like an imposter, or read always only as audience and never a participant.

So, reading The Nowhere Garden for the Innocent (無垢なる花たちのためのユートピア) just blew my mind. As a collection of SF short stories by an openly aroace author, it was what I had always wanted without realising. Science fiction and more broadly speculative fiction reimagines the world and enables the understanding of the world and people in ways otherwise impossible, which is one of the reasons I love the genre. But (though the number of books I’ve read so far isn’t large) it was the first work of speculative fiction that spoke to my experience and feelings specifically related to my aroace-ness in a way this book did.

The book contains six short stories, all science/speculative fiction. The rule-bending nature of speculative fiction enables us to imagine what ifs, but it also makes visible the author’s assumptions about the limitation to those imaginations, what they regard as essential or minimum for the story to be real in their worlds. Of course, books written by alloromantic and allosexual authors also often explore possibilities of relationships and sexualities, I know that. But it just feels different when it reflects the aroace experience. I didn’t know how liberating it feels to read stories where I’m not told I’m in the wrong for the lack of certain experiences or feelings, implicitly or explicitly.

I hadn’t understood the true importance of representation in media, especially that of aro people, until I read Loveless by Alice Oseman (whose protagonist is aroace) and watched Little Women (2019) (whose protagonist Joe who I interpreted as an aro icon, largely thanks to Sounds Fake But Okay podcast. My fave pod btw). Recently, I have also been rediscovering the power of fanfiction. And now, I have an even deeper understanding of what it means to have a piece of work in your favourite genre that you can see yourself in, and whose author clearly states their wish to create works in which they battle against amatonormativity, and in a language you grew up reading books in, which for me is Japanese. I’m now more jealous than before of the majority of the people who I suppose have plenty of books they can relate to in this particular sense (which is a fresh surprise to me every single day, what do you mean sexual attraction and games of romance are real and not fake?) (I am joking, respectfully).

I don’t want to spoil the book so won’t write too much about it here, but what I found to be one of the undercurrents in the book is the power of writing itself. It’s about how much writing stories and letters and diaries and memoirs and names might mean to somebody who might be looking for something or somebody. And, reading the book, I realised a special impact that fiction has on me. Works of fiction enable a kind of empathy different from the kind that nonfiction offers, like interviews, scientific books or even tweets, though they have also helped me. Fictional stories enable the reader to immerse themselves entirely in the world and identify with the characters. That is how I feel reading fiction, especially speculative fiction. And when identities often invisible are represented there, it can act like a special kind of affirmation that yes, a person can feel like that, and yes, it is a way to exist in the world and to interact with other people.

So I’m glad this book exists, and that I had the chance to encounter and read it. Stories save people. I hope people keep believing in the power of writing and storytelling, because now that I know books like this one can and do exist, I don’t feel as much like crying in a bookshop.

--------

無垢なる花たちのためのユートピア (The Nowhere Garden for the Innocent), Megumi Kawano - in Japanese

Loveless, Alice Oseman

SFBO Little Women episode

(This post was originally posted on my previous account @seasidesunset on 09/08/2022)

1 note

·

View note

Text

pardon me thinking about the aro community again.

it would be nice to go five minutes in the aromantic tag or on a new aro-centric blog id like to follow without running into a bunch of posts outta nowhere about how xyz types of aros are the ones who are Accepted Or Normalized and how abc types of aros are the ones who are shut out and ostracized in the community and out of it because like…. it really just seems like everybody feels that way. EVERYONE feels like they’re the ones who are being uniquely shunned by everyone else and not really accepted or supported and like yeah, we’re all being impacted by amatonormative society and arophobia, sometimes in differing or contradictory ways, but that’s not the fault or responsibility of other aro people who have different experiences or relationships to their identity? nobody else feels supported or accepted either and all these posts accusing other aros of Having It Better Or Easier is just misdirected anger that’s aiming at people who don’t deserve it and also aren’t being supported.

like anecdotally, in the same day i see a dozen posts about how romance-favourable aros need to be supported and validated and recognized because they’re silenced and shunned in the community, and also a dozen positivity posts or information posts about romance-favourable aros. and then the next day i see a dozen posts about how non-partnering aros who don’t want any kind of relationship romantic or otherwise need to be uplifted and supported and validated and given more attention and voice because THEY’RE silenced and shunned in the community, and then also a dozen positivity posts and informative posts and supportive posts for that demographic.

there’s no explanation other than we all feel like this all the time and it really feels like there’s a lot of misdirected and unearned hostility going around that’s only serving to make everyone more resentful and upset. im sorry people feel this way. i also feel this way. but accusing other members of your community of getting too much support (or even sometimes being responsible for your own feelings of alienation!) is just not it.

#gav gab#aro blogging#aromantic#there’s today’s thoughts#feel free to reblog btw i'm thinking out loud but if it resonates it's yours

776 notes

·

View notes

Text

For some reason, everything about Elemental just annoys me.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

it's aromantic spectrum awareness week. so i guess i'll talk about identifying as demiromantic and what it means for me.

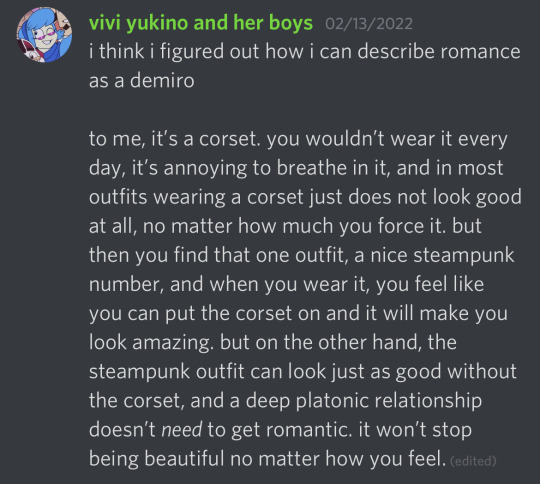

for the longest time, i would say things like "i could be arospec, but it could also just be trauma from my last romantic relationship", as if that made it any less legitimate. but sometime earlier this year, i just thought "you know what? i should be kinder to myself. even if i'm not right about this label, it still comforts me in the current time. besides, my identity and labels have changed so much ever since i first thought i could be queer, and there was a time when it comforted me to identify as a lesbian, so why not this?" and so i did. it's just really freeing to not have to worry about romance as much as i did. i'm a relationship anarchist anyway, so i have no desire to seek a relationship that is romantic. i'd rather just have good people in my life and let the relationships define themselves separately. amatonormativity is a poison and the ways in which i identify are slow working anecdotes. i'm just happy to not worry about romance as much these days. i don't want to force it. if it happens, it happens.

as for how i see romance, i'm just gonna use this discord message to describe it because i honestly think i hit the nail on the head the first time

once again, happy aro week everybody!!

167 notes

·

View notes

Note

You've got me thinking about this theoretical orgy.more than I should. How would that affect their friendship dynamics? Like hey we're just friends and we hang out but I also saw you get picked down last week

Just curious what the aftermath of that would be lol

i know this is a very queer aspec take but i am a firm believer that fwb or one-off sex with your friends doesn't have to be weird unless you make it weird. i think it would become a funny and cute anecdote they bring up to tease each other later in life

and also like... theres a certain level of of taking the setting into account, i think as well. the entire towns magic, your friends include a changeling, a fairy prince, and witch youve seen breathe underwater and sit in campfires, and a guy who can magically compel anyone to do anything. the fairy prince's mom is an eldritch horror the size of a county. you were all present at an event in which you got possessed by a ghost and tried to kill your classmates.

at that point like alskdjalkjds who cares about amatonormativity? why SHOULDN'T you have some one-off sex with your hot friends that you can laugh and tease each other about afterwards?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why identifying as aromantic is important to me (as a 36-year-old woman)

Submission to the October 2020 Carnival of Aros on the theme of ‘Prioritization’.

I identify as aromantic asexual (aro/ace). Both parts of that identity are important to me, but the aro one particularly so. Why? Because at 36 years old, society’s amatonormativity has more of an effect on me than its allonormativity.

In your teens and twenties, sex is a huge deal. There’s a lot of pressure to have sex and to be sexually desirable. But by the time you reach your mid-30s, this eases off. Your allosexual peers’ obsession with sex starts to wane, and you find less conversations about it taking place in your everyday life. In fact, if I were to admit to a 30/40/50-something allosexual person that I’m just not that interested in sex, I reckon there’s a good chance I’d receive a nod of recognition.

However, if I were to say that I’m not interested in having a relationship? That I intend to be ‘forever alone’? Well, that would raise eyebrows. For in amatonormative society, partnering up and settling down with someone, in the form of a mutually exclusive, ‘romantic’ relationship, is deemed inevitable; essential; the natural order of things. As you get older, society can (just about) countenance you not wanting sex. But it can’t comprehend you wanting to remain single.

When younger, aro people can get away with saying things like, ‘oh, I’m not looking for a relationship’, or, ‘I’m not interested in getting married’, in response to those seemingly innocuous, everyday questions we all get asked such as, ‘have you got a partner?’ and ‘are you married?’ Why? Because people assume that’s just your age talking, not your orientation. However, as you get closer to 40, being asked these kinds of questions can fill aro people with trepidation. How to explain that you’re just not that way inclined, when the overriding message from society is that you should be?

I remember a work lunch a few years ago, at which the conversation amongst my colleagues turned to talk about their husbands; how they met them; how they popped the question. Obviously, I had nothing to share on this topic, but that was okay; in my colleagues’ eyes, I was still young, with plenty of time to find My Man. I do wonder though, had I stayed in that job, how my colleagues’ attitudes towards me might have changed as the years went by and I continued to stay single. How would they have accounted for my singleness? With open-mindedness or prejudice?

For this is another issue aro people face as they get older. As the years go by, you become more conscious of what your family and any long-standing friends/co-workers might be making of your perma-singleness. Do they think me socially inept? Emotionally under-developed? Frigid? Pitiful? Just… not normal? Such is the stronghold amatonormativity has over our lives, that to lead a single life leaves you open to being perceived in all sorts of narrow-minded and unkind ways.

This is why claiming an aromantic identity is so important to me at this stage of my life. Whilst I’m still not really ‘out’ as aro, just coming out to myself has made all the difference. Now I know who/what I am, people can make whatever assumptions they like about me; that I’m a socially inept loner, whatever; it doesn’t matter. Knowing I’m aro, I feel the sting of the prejudicial attitudes our hetero/amatonormative society has towards single women a lot less, and am a lot more secure in myself.

Knowing I’m aro also helps when it comes to just being able to deal with everyday adult conversation; so much of which is centred around people’s dating lives, their married lives, their coupled-up nuclear family lives. For alloromantics – i.e. the majority of people – their ‘romantic’ relationship, and the family they create around that, is the very foundation of their lives. So, of course this ends up being the subject of a lot of everyday chit-chat, whether at the family dinner table or round the office water cooler. But for those of us who are aro/arospec, these most ‘normal’ and mundane of conversations can be awkward at best and alienating at worst.

My aro identity provides a much-needed bulwark against this. Before I discovered aromanticism, when I found myself in conversations about marriage and dating and settling down, I would often end up feeling insecure and embarrassed because my lack of relationship experience meant I had no similar anecdotes or stories to share. And even though I knew I didn’t actually want a relationship, and felt on some innate level that I was destined to stay single, this didn’t stop me from wondering whether the fact I’d made it all the way to 30 without ever having been in a relationship, or gone a date, meant there was something wrong with me. If I hadn’t discovered aromanticism, I can imagine these feelings of shame and embarrassment would only have intensified as I got older.

But now I know I am aromantic, I understand my non-existent relationship history to be a sign of my aromanticism, rather than of there being something ‘wrong’ with me, whether socially, emotionally, or physiologically. Again, this doesn’t mean I’m at the stage where I feel comfortable being all ‘I’m aro!’ when talking to people. But it does mean I can hold my head a bit higher when I find myself caught up in conversations in which everyone’s going on about their love lives.

As I get older, it’s my aromanticism that makes me feel queer in the world. My peers, siblings and cousins are coupling up and settling down, and here I remain, steadfastly single. As a result, I become more conscious of how my lack of romantic attraction sets me apart from others more than my lack of sexual attraction. No one’s quizzing me on the details of my sex life, or asking me who I ‘fancy’, anymore. But people do enquire about my relationship status. And people are likely to make all sorts of not-very-nice assumptions about that 30/40/50-something woman in their midst who continues to stay single. This is why, now I’m in my mid-30s, I have more of a need to give a name to, and to understand, my lack of interest in romantic relationships, than I do my lack of interest in sex. Claiming an aromantic identity helps me to navigate the amatonormativity which is all-pervasive in everyday adult life; and to navigate it with pride.

#aromantic#aromanticism#asexual#asexuality#aroace#aro pride#amatonormativity#allonormativity#permasingle#single life#carnival of aros

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I've been trying to figure this out for a long time now and it still confuses me a lot, so: how do I know if I'm arospec or if I just have commitment/trust/intimacy issues? I believe my experiences with romance would fall into aroflux and/or lithromantic, but I'm too young to be sure of anything and my feelings could be affected by thousands of things! I know that I don't really need to stick with a label for the rest of my life and that it's okay to be questioning, but discovering the cause of my (probable) aromanticism would help me a lot.

Well, for starters, being aro and having commitment/trust/intimacy issues aren’t mutually exclusive. Some aros struggle with those, but others don’t, and some alloros struggle with them, while others don’t. Furthermore, if you don’t feel comfortable with commitment/trust/intimacy right now (or ever), that’s fine; some people might see it as an “issue” with an obvious “cause” that needs to be “fixed”, but that “fixing” usually involves amatonormative and anti-aro behavior, so take that “advice” with at least a mountain of salt.

With regards to age, I’m always skeptical of the argument that someone’s too young to know their feelings or orientation, especially if it’s something they’re thinking about. (After all, who says that straight kids are too young to know they’re straight?) Plus, we have some science that suggests that people on average first feel sexual attraction when they’re ten years old, and if anecdotal evidence is anything to go by, that’s probably about when people start experiencing romantic attraction.

Hope that helps, as always feel free to ask for clarification/any follow up questions.

#ask#anon#original#questioning#questioning orientation#questioning aspec#questioning aro#questioning aromantic#Anonymous

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Makes Us Human, Part One

Moll of Sirenne needs prompts in their girdle book to navigate casual conversations, struggles to master facial expressions and feels safest weeding the monastery's vegetable gardens. Following their call to service, however, means offering wanderers in need a priest's support and guidance. A life free of social expectation to court, wed and befriend does outweigh their fear of causing harm—until forgetting the date of a holiday provokes a guest's ire and three cutting words: lifeless and loveless.

A priest must expand a guest's sense of human worth, but what do they do when their own comes under question? Can an autistic, aromantic priest ever expect to serve outside the garden? And what day is it...?

Contains: A middle-aged, agender priest set on defying social norms around love; an alloromantic guest with a journey to undergo in conquering her amatonormativity and ableism; and an elderly aromantic priest providing irascible reassurance.

Content Advisory: Depictions and discussions of ableism, amatonormativity and dehumanisation, particularly with regards to autism and aromanticism. Please expect additional background references to partner abuse and dysfunctional relationships, along with a side mention of magic causing harm to animals. This piece also includes reflections on non-romantic love's being pushed as a second-best "humanising" quality on non-partnerning, aplatonic and neurodiverse aros.

Length: 4, 946 words (part one of two).

Note: This is the newest entry in my tradition of Not Valentine’s Day Aro Stories posted on Valentine’s Day. No familiarity with my other Marchverse stories is needed, although it does obliquely nod at events referenced in Love is the Reckoning.

You think love is what makes us human, if you must choose one quality?

Moll opens their girdle book and, without looking, sets their fingertip by a word written a third of the way down the page. Gardening. Sighing, they buckle the book closed and drop it back into position at their hip. Sirenne’s greenhouses and vegetable gardens, in their midsummer bounty, gift the monastery a glut of corn, beans and cucumbers; they can start breakfast’s conversation with that observation. The kitchen’s current tendency to add corn to foods and dishes that don’t usually encompass them offers another direction, along with more anodyne comments about weeding and Sirenne’s scores of potted plants. Simple enough, as discussions go.

When will their calling start to feel simple?

True, they count ownership of their red robes in weeks and months, the scar on their shoulder still pink. The brown belt of a novice priest bears the girdle book and a leather pouch, its length crisp and unmarked. Five years of study can’t yet earn the confidence of experience: by logic’s metric, it’s unreasonable for Moll to expect mastery in this new art. How can they compare the difficulty of their new work to the ease they owned in the old? Aren’t they creating their distress by anticipating the unrealistic?

“Fifteen years with the Seventh,” they mutter under their breath as they walk to the serving tables and fill a bowl with steamed rice and quinoa, today drizzled with stewed apricots. A waiting acolyte, standing behind the array of dishes, pays Moll’s murmuring no mind. “It’s only been a little over five, here. Don’t compare them.”

They add another ladle of apricots to their bowl and turn towards their table, tucked to the side of the great hall—away from the clatter of the kitchen doors, close to a window looking onto one of the monastery’s fern-clustered courtyards. Moll dislikes navigating all the chairs filled by guests, acolytes and guiding priests, but they’ll accept that thrice-daily annoyance for the comparative quiet of their corner.

Today, despite the hall’s great arched roof and echoing tile floor, the noise isn’t as bothersome.

Only when they reach their table do they realise why: one advising priest, her red robes belted with green, joins the gaggle of guests and acolytes. Where are the others? Did something happen overnight? The Guide misses as many meals as she attends, but never has Moll seen so few of Sirenne’s senior priests at breakfast. Frowning, they look to their acolytes sitting at the middle of the table. Dare they ask? If something serious has happened, wouldn’t Moll already know? Why risk distressing James by calling attention to something that may lack any import?

Neither appears to mark anything amiss.

“Good morning.” Moll sits opposite James and across from the brown-robed acolytes, working to keep their voice even and low. James regards the slightest abruptness in Moll’s speech as indicative of anger or disgust, and they prefer no further misunderstandings. “I see that the kitchen serves cornbread, creamed corn and corn fritters this morning?”

The acolytes nod vehemently.

James, staring at her plate, pays Moll no attention. She’s a small and delicate woman, pretty as some reckon such things. Fine chains of embroidery decorate the cuffs of her linen shirt and the panels of her grey waistcoat; studs carved like silver roses sparkle in her ear lobes, while matching combs and pins hold back her silky curls. Paint darkens her lips and evens a complexion in little need of it; no callus of pen, needle or weapon roughens her soft fingers. She’s elegant like a fashion plate in a book, but the illusion breaks when Moll looks to her nails, bitten down to the distal edge. A habit, they know, discouraged in the classes of people needful of donning powder and paint before breakfast at a secluded monastery.

Never has she bitten them in public, and she rejected Moll’s suggestion of fidget tools as though offended by their observation of her need. Even their usual use of a weighted, beaded cord while talking drew her ire: it’s manipulative, she said, as though their stimming exists only in relationship to the shame social niceties require nobody mention, to pressure me by using something I have refused in front of me.

She did, yesterday, observe the morning greeting.

“Corn wouldn’t be so bad,” Alicia says, her eyes flicking from James to Moll underneath an untidy mop of red hair, “if they’d do something new with it.”

“Don’t say that!” Ro howls, poking Alicia in the arm. At eighteen, he isn’t much more than a child, gangly and frenetic. Remembering the reasons underpinning his service during meals—to help a guiding priest maintain a casual conversation before their guests—isn’t yet second nature. “They’ll be giving us corn in pudding next!”

Moll suspects they’re meant to learn from Ro’s impulsiveness as much as Ro should from their measured consideration.

Measured consideration is the polite way of saying “rigidly follows rules”.

“Corn custard?” Alicia grins and elbows Ro in the ribs. When he forgets his duty, she soon follows him.

“Don’t even say it! Don’t give them ideas!”

“Corn custard, corn custard, corn custard!”

James sits at the table as if unhearing, her lean hands pushing a piece of toasted wheat bread across her plate. She smells like jasmine, her perfume a foreign, expensive contrast to breakfast’s savoury aromas, Moll’s apricots and the damp, earthy scents of the courtyard. She smells like their childhood.

They hastily swallow a mouthful of their own breakfast, the grains mingling with the sweet fruit, before attempting a direct question. “Do you garden, James? I didn’t have the opportunity before Sirenne, unless I count the Warp’s tendency to provoke sacks of flour into sprouting seedlings overnight? I still know little, but I’ve learnt that I enjoy mucking about with a trowel.”

There: a question and a few personal observations. Isn’t that the mainstay of an acceptable social exchange? Three terms in the Seventh Western Regiment, stationed in the Warp during the Council of Advocates’ last attempt to settle that magic-twisted territory, have left Moll with a lifetime of anecdotes. Many—like the time a crate of fleece-lined coats outside the wards became a bleating collection of violently disfigured sheep—are best left unmentioned during meals, but magical wheat seems safe enough for breakfast chatter.

James, without blinking, pinches off a corner from her piece of buttered toast.

If not for a week’s observation, Moll may have thought her unable to hear or process.

“I hate gardening,” Alicia offers, after another look at James. “Dirt under my fingernails? I’d rather dust or wash dishes or sweep.”

Ro snickers. “Dirt? Of course—”

Moll taps him on the ankle with their bare foot.

“Uh … yes, I don’t like dirt, either. Because I hate laundry. Your hands get all cracked and dry. I’ve still got scars from when my skin split in winter. But when your father’s a launderer…” Ro shakes his head and glances at Moll. “What did you hate, in your old job?”

People who go through my wagons. Officers who refuse to follow needed precautions. The mouldy-citrus smell of warped, decaying magic.

Instead, they stop to think of something others will find relatable: Moll enjoyed the usual army annoyances of polishing boots and mending uniforms. The barracks brats of the Seventh always knew when their quartermaster passed a sleepless night, for they’d wake to find their newly-darned stockings laid out over their gear chests.

“Latrine duty. I didn’t dislike planning or digging, but cleaning up a latrine site isn’t enjoyable for obvious reasons. Soldiers left to unsupervised orders, however, have a marked tendency to the slapdash.”

Alicia, of course, pulls a face.

James turns away from Moll, her pressed lips and deep frown suggesting irritation or disdain.

Anxiety, too familiar a companion, sits as heavily in Moll’s gut as a month’s diet of wheat bread.

They can’t remember a time in childhood absent that pervasive sense of dread, the knowing of their having errored without cognition on how or why. Nor was their adulthood so free—the difference being that Moll had twenty years to learn the rules and rhythms of military life, and service in the Warp excused some of Moll’s habits and provoked similar needs in others. Then the Council surrendered to the Warp and disbanded the Seventh, leaving Moll adrift in a world governed by normal magic and unexplained rules.

Sirenne, where people communicate with clarity and directness about concepts brushed aside as unacceptable, should have offered refuge.

They eat, letting Alicia and Ro carry the conversation against the backdrop of James’s pointed silence. She only makes a few pointed grimaces when Moll speaks, picking her way through half a slice of toast.

After yesterday, they planned to offer James the morning for further discussion.

Today, in the absence of a proper breakfast and animus targeted at Moll, they’d best make it a priority.

When the acolytes clear away the dishes and the hall empties out with priests and guests going about chores or sessions, they stand, round the end of the table and bow at James. “Would you please come and walk with me?”

At first, it felt deceptive to string together words so unrelated to their intent. Honesty, to Moll, means saying what is meant: I want to have a private conversation about your mood and health, to help guide you in following the life’s path best suited to you. Gennifer explained, over several occasions, that while all believers know what a priest of the Sojourner means by “walk”, success rarely results from beginning said conversations with direct utterances of an uncomfortable truth.

They still don’t grasp the logic in that, but Moll now regards the script as a signpost marking the transition from breakfast’s communality to discussion’s intimacy. If Sirenne possesses an agreed-upon willingness to dishonesty between all parties, is it still a lie? A priest’s work doesn’t mean, Gennifer added, a strict adherence to direct honesty, and aren’t they supposed to be challenging the existence of an objective truth? Why should Moll’s regard become the defining metric of falsehood?

Priesthood requires accepting the unfading presence of an existential headache.

James rises, drops her spoon onto her plate with a teeth-jarring clang and follows Moll from the hall—offering, presumably, her consent.

Their favourite courtyard, as always, bears no tag of occupancy. A triangular space jammed between the kitchens and the Guide’s personal wing, it lacks the green softness of Sirenne’s other courtyards, instead beset with craggy planes of rock part-covered by draping vines. While few areas of the monastery don’t feature running water—its movement reflecting the Sojourner’s eternal journey—here a still basin houses pond fish and lilies. Other priests abhor the darkness and stuffiness caused by four walls and the slanting eaves above, but Moll appreciates the yard’s quiet. How do the others listen to running water for hours on end without succumbing to teeth-grinding annoyance?

They murmur the spell for a peach-hued witchlight, palm the resulting sphere and fling it upwards to catch on a trailing cluster of vines by the archway’s apex. “Please, enter.”

James folds her arms, passes under the arch and sits on the bench by the basin, staring at the white lilies clustered along one edge. The toe of her left boot, the leather polished near to gleaming, worries at a crack in the flagstones. “What.”

No lilt, no upturned voice. Probably not a question.

Moll moves to their usual seat. A pillow placed on a dip of the rocky wall provides a safe distance between them and their guests while offering the damp, loamy aura of fern and moss. They still can’t take ordinary nature for granted; they still wake in the night, startled to breathe air that doesn’t smell of rot. “I fear that I have caused you offense or hurt. I would appreciate knowing, if you’d be so kind as to explain, what I did.”

The difficulty in needing to ask people for explanations lies in their requiring them from those Moll has hurt. Some don’t mind, those who understand the cause of their ignorance, but too many become more offended when having to explain the how and why of something Moll should have known to avoid. If a quartermaster is expected to read another’s body language and glean its inspiring thoughts and feelings, guests grant far less leeway to a priest—no matter how much introductory explanation Moll provides about their autism.

They try, where possible, to describe situations and ask questions of other people, but how can they do so here? James is distressed enough to disregard the customs on which she sets such value; while she wasn’t friendly at breakfast, she didn’t direct her expressions at the acolytes. Moll, based on limited evidence, a reasonable assumption and their history, must have caused her mood.

Again.

James turns her head and shoulders away from Moll—almost putting her back to them while remaining seated on the stone bench.

“I apologise.” They bow as best they can from their seated position. “It’s unfair to place on you the burden of educating me after being hurt. I do wish to know how I can avoid distressing you in future, and I promise that I won’t be angered by your explanation. If you wish another priest to assist in—”

James whirls to face them with startling speed, her teeth bared in something close to a snarl. “What, so you’ll write it down in your book of things to remember?”

Talking, however abrupt and disagreeable, provides an entry into exploration. While a variety of considering or responsive silences should be recognised and supported in a healthy exchange, guiding is easier when anything expressive replaces the wall of sullen silence.

Even accusation and aggression.

“I don’t understand,” Moll demurs, letting their eyes rest on James’s face for fear avoidance suggests anger or insincerity. “Didn’t I explain sufficiently to you why I use my book?”

A guiding priest must, inquisitively, engage with their flock’s thoughts and feelings. Curiosity means putting aside judgement and listening, open-hearted, to the twists and turns of a path that lead to their conclusions. Curiosity means offering, as non-judgementally as possible, a more useful direction. Curiosity means listening to and acknowledging another’s criticism of their work. Curiosity means putting aside the last conversation Moll had with a guest about their girdle book … even as bile’s bitter sourness coats the back of their throat and tongue.

James snorts. She holds her chin high above the stiff collar of her shirt, her shoulders set, her hands folded in her lap. Even in session, she doesn’t forgo correctness for comfort. “You think that I haven’t seen you picking something to talk about each meal? Except you didn’t remember to write down what day it is, did you? You just ask completely irrelevant questions!”

What day…? They work through the shards of story James has shared, but none suggest significance of the day, week or season. She spoke, in short references, of a relationship fallen apart and a family taking the side of her partner, citing reasons of financial investment. She spoke of need for a temporary reprieve from both—threaded with the hope of return when her partner’s anger ebbs enough for normal’s resumption—but resentment colours her references to the friend that suggested sanctuary at a monastery. They know of no anniversary that lends one summer day such profound weight.

Perhaps her disdain draws from something she believes sufficiently communicated, conveyed in hints perceived by an allistic priest?

“I find participating in casual exchanges difficult. This book,” and Moll dips their chin towards their hip, “helps me engage in the talk many of our guests find comforting. Perhaps I mayn’t need it in future, but today I do.” Moll closes their fists and opens them, one deliberate finger at a time. Since fidgets provoke James’s anger, Moll possesses fewer ways to direct and manage their nervousness. “I am grateful for a tool that eases my navigation of unsuited customs. Do you have occasions where you would appreciate a tool to help you with something people don’t expect you to find difficult?”

Gennifer gifted them the girdle book a few months after Moll took the brown; the acolytes of Moll’s calling-year spent that evening offering suggestions and prompts. Sorcha and Oki passed the book amongst the priests until a score of hands filled the pages. For the first time in Moll’s life, they found themself surrounded by people more interested in helping them navigate expectations than in using their difficulties to void their position.

If not for the guests, Sirenne should have offered nothing short of paradise.

Even to think this borders on sacrilege.

“You’re a priest. You’re supposed to be…” James stares, shaking her head. “Or maybe that’s why! You don’t even know what today is, do you? It’s just another day to you—away from the real world, thinking you know anything!” Her voice edges on shrill as she leans forwards. “Is that why you all become priests? Because you’re not normal enough for anything but hiding here?”

Moll admits that their calling exists in part because of the similarities shared by divine and armed service. Both offer the comforting limits of hour bells, set times for work and play, assigned clothing, clear expectations around behaviour. While surprises happen, Sirenne and the Seventh provide rules and processes for how one responds; even the unexpected, in many ways, still owns a guiding spectre of regularity.

Structure, Gennifer summarised after Moll’s explanation. You need—thrive in—the structure.

The monastic life also permits and justifies their failure to navigate life and relationship expectations. A priest of the Sojourner needn’t avoid partnering, but such avoidance isn’t unexpected given their remove from circumstances that facilitate such relationships.

They knew, their boots crunching on the driveway’s blanket of fallen leaves and twigs, that this secluded compound will become home.

They knew, during their first gently-interrogative conversation with Gennifer, what new path their feet must follow.

Does that correlate to hiding?

“I was quartermaster for fifteen years in the Seventh Western Regiment,” Moll says quietly. “After the Seventh’s disbandment and my discharge, I was called to begin a new shape of service, in which I am recognised by the Sojourner and the community of Sirenne. May I ask what ‘normal’ means to you?”

It’s crass to draw James’s attention to their bare shoulders, one marked by their god and one marked by the Guide. What does the possession of either mean, anyway, if Moll doubts their ability to serve as called? They open and close their fists, lifting and lowering one finger at a time, until their body feels less likely to slip out of control.

James, her thin brows raised, stares at the basin and its lilies.

Remember your curiosity.

Curiosity, in the Warp, too often became lethal.

“Would you share with me your understanding of priestly service? Guests are often surprised by the differences between the monastic orders.” They try to smile. “I think that speaks to what the Sojourner preaches—that there are many pathways, often contradictory but always leading to the same place, to understand and honour hir. But it can, sometimes, make for confusion.”

Even her criticism, should it encompass substance and clarity, seems better than this wall of vague disdain interspersed with rejecting silence. Other than referencing a date on which Moll recognises no significance and objecting to their use of the girdle book’s prompts, she hasn’t provided actionable critique or evaluation. They forgot—or didn’t know—today’s significance. How can they rectify that without explanation?

James snorts. “That’s what you tell yourself.”

A woman so bound up in observing customs of dress and behaviour must intend her rudeness.

Should they admit defeat and take James to Gennifer for reassignment? Yet if something significant busies the Guide and her advising priests, Gennifer doesn’t need a brown-belted priest running for help with one guest in, comparatively, a trivial circumstance. Surely even a raw priest, who doesn’t need reminder lists for mealtime conversations, will navigate this situation without help? Isn’t this, then, a learning opportunity? If they can figure out how to gain James’s trust, will they make fewer mistakes with other allistic guests?

They draw a series of breaths—inhale, hold, exhale—but the nauseating anxiety now bears the edges of a restless, sweating panic.

“Yes, I do tell myself that,” they say as agreeably as possible. A display of receptiveness may help James feel comfortable with further elaboration, even though they don’t know why she made such a snide comment. “I do wish to better support you. Before I can do that, I need to learn from you. Every priest must learn from their guests; I just have a greater need than some.”

James looks down at their feet, scraping the soles of their boots across the tiles with a sound that sets Moll’s teeth on edge.

Breathe in, hold, breathe out. Exhale for as long as possible. Close fingers one by one, hold, open them again as slowly as possible. Breathe.

“That sound hurts my ears. Would you please stop?” Moll attempts, again, a smile, but even on the best of days and in the happiest of moods such an expression feels forced and unnatural. If only they could project an image of quiet harmlessness! How else do they manage a tension too often read as threatening when their lips don’t move the usual way? “Thank you.”

James stills her feet, staring at Moll with her head tilted as if to suggest that she looks through them to focus on the vine-shrouded stone behind.

“I understand that today has meaning to you,” they offer. Perhaps retreating to the one problem about which James has provided any clarity will encourage movement. “Would you share this meaning with me, so I can offer the specific support you need? I’ve missed your communicating it.”

As soon as the they say “me”, they realise that an allistic priest with an allistic’s intuitive understanding of social interactions will instead have asked an unrelated question or offered a distracting observation on an unrelated subject.

As soon as they say “me”, they know they have handed James all the excuse she needs.

They just don’t know why.

She leaps upright, her hands trembling. “How are you going to help if you don’t even know? How are you going to help me with my partner, when you don’t know why today matters? Why I have to be alone today of all days, and how awful that is—but you just want explanations like you’re a child at their first solstice, too young to know anything! What’s the good of talking to you when you’re just a statue, lifeless and loveless? Look at you—you don’t even have an expression!”

Her brown eyes glisten as though she stands one wrong word away from tears.

Moll opens and closes their hands, one slow finger at a time.

Share, Oki advised every shadowing. Don’t burden them with your pain, but don’t secret your own struggles. Show them that you walk this road because you know theirs.

One word, though, they are hesitant to mention.

Perhaps their aromanticism, the sense Moll has owned as for as long as memory that they don’t desire romantic partnerships, is obvious to others. Perhaps James believes that an autistic, with stiff words and a book of conversation prompts, must be aromantic, both “lifeless and loveless”. Maybe she believes aromanticism accompanies an identity equally misunderstood as a detriment or shortcoming. Doesn’t she believe, at least, that those called to priesthood have surrendered any validating sense of what she considers normal—and, therefore, of value?

Convention, for all that she privileges it, nonetheless sent both sheltering beneath Sirenne’s roof.

“I’m truly sorry that you’re hurting and that today is difficult for you. I will do my best to help you, but the more you’re willing to share, the easier I will find it.” Moll speaks with measured care, pausing between each word in the fight to keep their voice from breaking. Measured means rigid. Rigid … isn’t that another way of saying “lifeless”? “My autism or aromanticism, however, don’t mean we lack humanity in common, or that I haven’t struggled with my family or departures from my road—my own despair and illnesses. I haven’t experienced your precise circumstances, but that doesn’t mean I don’t believe in your struggles or won’t offer a sympathetic ear.”

How can they provide that if she won’t explain her needs?

Lifeless. Frantic limbs and a wild voice, emotion given movement and language, also earns them censure—accusations of immaturity or aggression. Moll’s big, broad body and limbs don’t permit even dangerousness’s suggestion without provoking restrictive consequence. No, they can’t expect her to understand their inability to recollect freedom of reaction, emotion or speech. They don’t expect her to understand that adulthood’s repetition has rendered a seemingly-unnatural control all but innate. Can’t she at least assume that if Moll can master that acceptable state of allistic-flavoured emotional expression, they will?

Loveless. No, they don’t feel in any way categorisable as “love”. They’re not drawn to friends or partners in ways that suit, even non-romantically, the word’s sense of passion and vibrancy; it doesn’t fit their connection to people, labour or place. Their calling to service is too powerful and all-encompassing to be love. Such a general word, often used to describe feelings and actions contradictory to its given purpose, feels ill-suited.

Why must it be a moral failing to use words other than “love” to describe their relationships and feelings? Why must complex emotions be reduced to a binary of hate and love? Why must people replace the pressure to love romantically with the pressure to at least avoid accusations of lovelessness?

“Lifeless” devalues their best attempt to oblige other people’s expectations.

“Loveless”, not synonymous with loathing or disregard, shouldn’t serve as any kind of criticism. James loves. Which of them, today, is the crueller?

Maybe Moll has constrained their feelings for too long to permit a broader, warmer range of emotion.

Maybe their need to match feelings and experiences to words’ exact specifications means they, unknowingly, feel something allistics name “love”.

Maybe the stories that explain and identify love hold little relevance in real life, and people not Moll better accept the chasm standing between idealism and reality.

Maybe the reasoning doesn’t matter: the Sojourner has never required that her followers love.

What if, though, they’re better suited to a trowel or chopping knife than the careful, subtle art of guiding their guests? What if Moll can’t help James because of the qualities they don’t experience or the relationships they don’t desire? What if lovelessness and lifelessness, even best regarded as neutral states of being, render them ill-suited to the work?

“You’re like a puppet—moving your wooden lips, saying the words. But you don’t know anything about … about really being human.” James folds her arms across her body before turning towards the arch, her chin held high. “There’s no point. Not with you.”

No, there isn’t. She needs a priest who won’t make her feel distanced by their inability to share her experiences. One who, in curiosity and kindness, can explore and sympathise with her pain-born feelings and judgements. One who doesn’t feel slapped across the face and punched in the gut by three words: lifeless and loveless.

They understand the process. Pluck out the least-acceptable aspects of aromanticism and autism, disguise them as general qualities society finds objectionable and wield them at the vulnerable—prejudice now concealed under the thinnest veneer of acceptable disregard. Awareness doesn’t ease their hurt.

Wooden. Puppet. Statue.

Inhuman.

She halts at the archway, gesturing in their direction. “See? You aren’t even saying anything now! You’re—”

“Pain!” The word spills from Moll’s lips with shocking vehemence. “You think love is what makes us human, if you must choose one quality? No, humans are pain, not love—the pain of having our worth denied, the pain of injury and loss, the pain of our cognisance of our mortality, the pain of fear, the pain of being overlooked or ignored, even the pain of having our pain denied! Who doesn’t endure against the hurt of being told in word or action that we aren’t worth kindness?”

James stares at Moll in an aghast, still silence.

“You think I can’t know you? If you think, in your pain and ignorance, that I haven’t had someone demonstrate that I’m undeserving of respect, you have done so just now! You sought to strip away my humanity, because you think cruelty will give you back the power torn from you. It won’t. It only makes you cruel. It only envenomates another.” They rise and walk towards the archway, fighting to keep their steps slow and hands loose by their sides. “Because you misunderstand your own humanity, you gave me what makes me as human as you—pain. Will you say it again, now, why I can’t guide you?”

Her lips part as though about to speak, but no sound emerges.

“I have consented to guide you to your rightful path. I haven’t consented to your disrespect.” Despite their efforts, Moll’s bare feet smack against the stone as they step past James into the fern-lined pathway. “Gennifer will assign you to another priest’s care. I won’t spend a moment longer with you.” Just for a moment, they adopt the snapping bark mastered with the Seventh: “Come!”

James moves as though afraid to make the slightest noise, hanging back a few steps behind with the nail of her pointer finger clasped between her teeth.

#aro writing#aromantic#arospec creations#loveless aro friendly#lovelessness#loveless aro#loveless aro feels#nonpartnering#aplatonic feels#aromantic and aplatonic#aplatonic#aromantic and autistic#autism#aromantic and agender#fiction#original fiction#original fiction and prose#fantasy#short fiction#what makes us human#long post#very long post#amatonormativity#ableism#ableism mention#dehumanisation#aro antagonism#nonamory#nonamorous#valentine's day mention

21 notes

·

View notes