#achaean omens

Text

Good Omens: Lockdown, Aziraphale’s SAD-ASS desk, and how they get to 'Our bookshop' in S2

Welcome to part 2 of me reading reeaally far into the Good Omens: Lockdown video! (part 1 from Crowley's POV here) This post assumes the item choices in the Lockdown visuals are intentional. What follows is going to be my headcanon regardless, but if you're into the Word of God, Lockdown is canon 'If you want it to be.' and I want it to be, sooo checkmate! >;D

Also this is something of a long boi (~13 minute read without following the links >.>), so if you're into unhinged analysis of details and literary references that indicate Aziraphale is in his longing era and want to learn more about author and fave-of-Gaiman, G.K. Chesterton, either get comfy or mark this to read later when you have time!

C: What?

A: *somehow surprised even though HE CALLED* A-ah, hello. It's me!

C: I know it's you, Aziraphale.

A: *regaining composure* Yes, well, just calling to see how you were doing in lockdown.

The video starts with shots of Aziraphale and Crowley's da Vinci sketches (and some sushi remnants)... Babygirl is flipping through the time-goes-too-fast-for-me version of a facebook album, thinking about his crush. vERY chill of him. (also the paper looks new and he's eating on top of them, suggesting these are prints and he has multiple copies of them... sooo normal)

If we look closer at the still of Crowley's portrait, we can see part of the spine of a book that reads Kei- Chesterto-. This is, of course, author Gilbert Keith Chesterton, to whom Neil and Terry (and Crowley) dedicated Good Omens:

The authors would like to join the demon Crowley in dedicating this book to the memory of

G. K. Chesterton

A man who knew what was going on.

In this post by @azfellandco about Chesterton, you can see a photo of the dedication page and also read the book excerpt where Crowley describes Chesterton as 'the only poet in the twentieth century to even come close to the Truth'.

C: I'm bored. I'm so very very bored - transcendentally bored. There's nothing to do here!

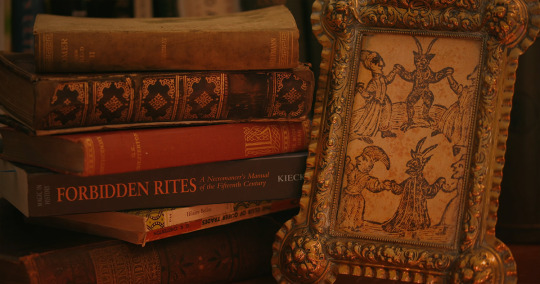

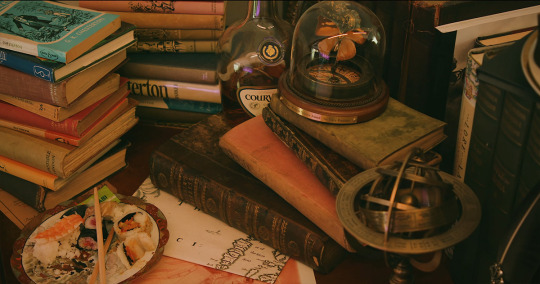

As Crowley is explaining his nap contingency plan, we get a shot of Aziraphale picking up his mug of hot chocolate, then the image below of the 2/3rds gone bottle of Courvoisier cognac (i mean maybe he is baking with it let's not jump to conclusions), and then the stack of books beside a framed woodcut print of witches dancing with devils...

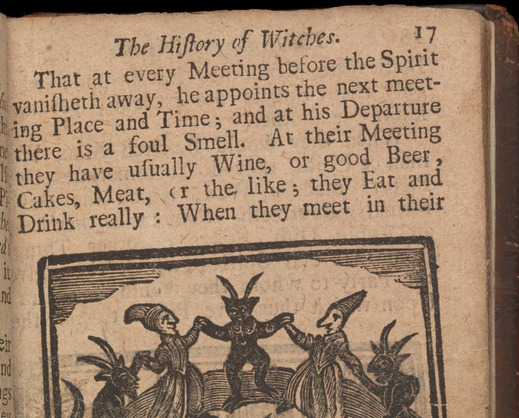

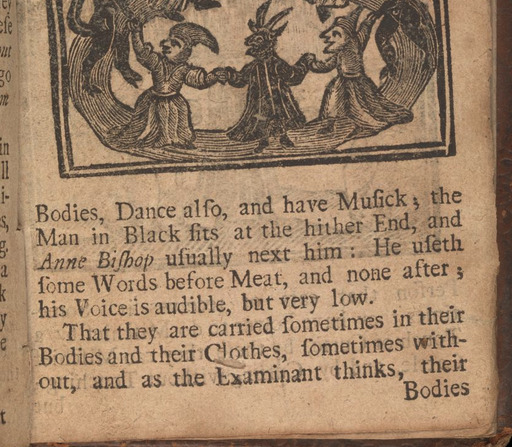

...that I used reverse image search to trace back to page 17 of a book from 1720 called The history of witches and wizards: giving a true account of all their tryals in England, Scotland, Swedeland, France, and New England; with their confession and condemnation.

Interestingly, the text above and below the picture reads:

At their Meeting they have usually Wine, or good Beer, Cakes, Meat, or the like; they Eat and Drink really: When they meet in their Bodies, Dance also, and have Musick...

Beside the framed print of Aziraphale's idea of a really great night out is a stack of books that includes (going from top to bottom):

Homer's The Iliad, Book 2

Orthodoxy by G.K. Chesterton

Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer's Manual of the Fifteenth Century by Richard Kieckhefer

a book by Hilaire Belloc with no visible title

The Club of Queer Trades by G.K. Chesterton

The Iliad (according to sparknotes) has the following major themes:

....Interesting, ok. Book 2 in particular starts with a god (Zeus) messing with someone (Agamemnon) via a dream that says he will be successful in taking Troy if he launches a full assault, balls to the (city) wall. Agamemnon, who is supposed to be leading the Achaean army to conquer Troy, believes the dream but then in a weird twist decides to test his army and be like 'jk actually I'm giving up and going home' and then is mad when the soldiers are like 'sick, to the boats!' Then Odysseus, who sparknotes tells me is the most eloquent of the Achaeans, gives an impressive speech to inspire the troops and reminds them that they vowed 'that they would not abandon their struggle until the city fell.' ...No way that could worsen Aziraphale's internal conflict about being a bad Angel who thwarted the Great Plan. >.>; Orthodoxy we'll get to in a second.

Then there's Forbidden Rites which is a medieval necromancy guide translated from Latin with added commentary - Aziraphale is perhaps studying occult topics in an attempt to understand Crowley better? And then there's the Hilaire Belloc book on top of the second Chesterton book, a collection of related stories/episodes?, The Club of Queer Trades. The book's Wikipedia page says:

Each story in the collection is centered on a person who is making his living by some novel and extraordinary means. To gain admittance [to the Club of Queer Trades] one must have invented a unique means of earning a living and the subsequent trade being the main source of income.

Aziraphale and Crowley have rather novel/extraordinary jobs and they're both peculiar-queer and gay-queer. Neat. The narrator in the book is named Charlie "Cherub" Swinburne - also neat. >.> He goes on an adventure with his friend, a retired judge and president of the Club of Queer Trades, Basil Grant, (who Oct 2021 GoodReads reviewer Cecily said is "described as mad, mystical, and a poet, with almost no friends, but who “would talk to any one anywhere”) and Basil's younger brother, a private detective named Inspector Constable Rupert Grant. The last line of the book is:

Thus our epic ended where it had begun, like a true cycle.

(something something "It starts, as it will end, with a garden.")

Anyway, the Belloc book and The Club of Queer Trades are placed back to back in such a way that they almost look like they could be one book with two different aesthetics, or... two halves of a pantomime beast?! (stay with me I needed a segue)

Belloc and Chesterton have what is essentially a ship name:

It was coined by George Bernard Shaw (if you are like me and didn't know why you've heard of him: he wrote, among other things, Pygmalion, which was adapted into My Fair Lady). Shaw apparently liked to gossip about Belloc and Chesterton with H.G. Wells (again if you're uncultured like me: he wrote, among other science fiction-y things, The War of the Worlds).

In the Feb 15, 1908 issue of The New Age newspaper, Shaw said:

He continued:

"Chesterton and Belloc are so unlike that they get frightfully into one another’s way. ... They are unlike in everything except the specific literary genius and delight in play-acting that is common to them, and that threw them into one another’s arms.”

Shaw says Belloc is 'a bit of a rowdy', and 'cannot bear isolation'. Hmm. Then he says Chesterton is 'friendly, easy-going, unaffected,

gentle, magnanimous, and genuinely democratic'. HMM.

“They share one failing—almost the only specific trait they have in common except their literary talent. That failing is, I grieve to say, addiction to the pleasures of the table.”

Ok ok I think we can see where this is going.

(^ from Staged S3E6)

Now, someone did ask Neil Gaiman about this similarity, and he said the Lockdown video was filmed by Rob Wilkins in Terry Pratchett's library, and that he suspects 'Belloc is there because he was on Terry's shelves beside Chesterton.' And it MAY VERY WELL BE that NONE (0) of the book titles are meant in any way other than 'these are books from Sir Pratchett's library that looked nice on camera and ofc we wanted some Chesterton refs and maybe some demon-y stuff for Crowley' but that is WAY less fun so I am choosing to take them as intentional: these are books Aziraphale is actually reading (along with the sushi and many cakes he is actually eating). Let's put ourselves in Aziraphale's shoes and try to imagine how it would be to read this stuff during lockdown while you pine for a demon with slinky hips after you got in big trouble at work for Armageddoff (and work happens to have defined your worldview and general purpose in life).

C: welll... ngk then people might follow my bad example and get ill. Or even die—

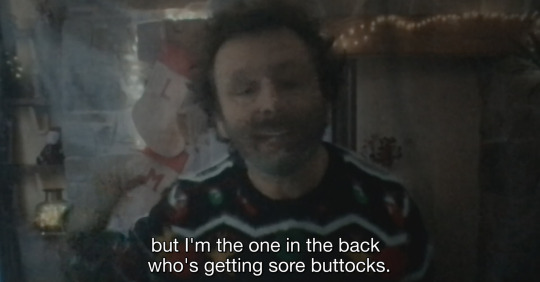

As Crowley acknowledges that he ought to be out making peoples' lives worse, we see Orthodoxy by Chesterton open on the desk.

Orthodoxy is described as a ‘spiritual autobiography’ and is considered a classic of Christian apologetics, i.e. the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines (in this case, Catholic) through systematic argumentation and discourse. Wikipedia also says Chesterton's The Everlasting Man contributed to C.S. Lewis' conversion to Christianity, so overall it sounds like he must've been fairly convincing. (and so maybe reading it also poked at that work-related-but-religious-trauma-adjacent stuff Aziraphale has going on?)

You can read Orthodoxy (and probably any of the books I mention bc theyre all old) on project gutenberg but I will include this part of what is shown on the righthand page bc it just reminds me (and so probably Azirapalala as well) of a certain angel squeaking happily at a nebula:

"I felt economical about the stars as if they were sapphires (they are called so in Milton's Eden): I hoarded the hills. For the universe is a single jewel, and while it is a natural cant to talk of a jewel as peerless and priceless, of this jewel it is literally true. This cosmos is indeed without peer and without price: for there cannot be another one."

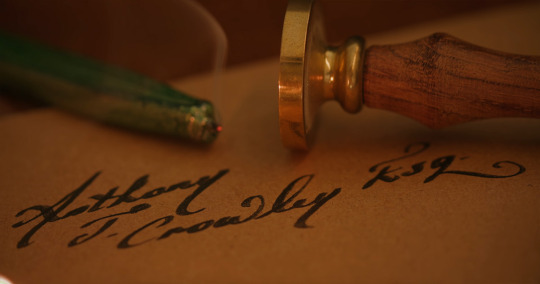

Ok great, so Aziraphale is diving into the works of one of Crowley's favorite authors bc he misses him, that's cute. What else? Oh he already wrote him a letter right before calling - THE WICK ON THE WAX STICK FOR THE SEAL IS STILL SMOKING. sO CASUAL asdashgfjds

something something 'either call on the phone and talk, or appear mysteriously; don't do both'

When Aziraphale gets to 'I've never had so few customers, not in two hundred years!' We get a close up of this glass of cognac with droplets still on the side — I take back what I said about baking, Aziraphale is drinking it~

He's not drinking a wine, eg Châteauneuf-du-pape, which would be ~14% alcohol by volume (ABV), or a sherry (15-20% ABV); he is drinking Courvoisier cognac, a hard liquor (40% ABV). Crowley's Talisker whisky is 48.5% while we are on the topic. This is stronger than what Aziraphale usually drinks which means... he could be a bit tipsy.

As Aziraphale starts talking about the would-be cash-box burglary, we get this wide shot of the desk:

In the top left hand corner, we see two stacks of books, most (all?) of which appear to be Chesterton when I zoom in. Some of them have Chesterton's name visible on them, others have the publisher name 'Darwen Finlayson' on them, which according to my googling is a house that published several of Chesterton's works. If Chesterton was truly 'a man who knew what was going on', then perhaps this is Aziraphale seeking not just to feel closer to Crowley, but also to make sense of the warring ideas in his mind. Interestingly, Chesterton has also been described as 'The Eccentric Prince of Paradox'.

C: *clearly amused* Did you smite them with your wroth?

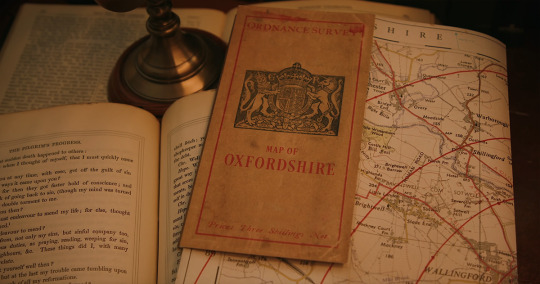

The screen then shows two occult-y books and a flickering candle (lower left image). Then Aziraphale explains about his cake~, and as Crowley cuts him off because he's about to nervously ask to come over bc he is so so lonely & down bad for a certain angelic bookworm, we see a map of Oxfordshire on top of Pilgrim's Progress (lower right image).

The two books beside the candle are Satanism and Witchcraft (presumably the 1862 book by Jules Michelet that comes up when I search the title), and another called Magic: An Occult Primer.

Satanism and Witchcraft is described on Wikipedia as 'notable for being one of the first sympathetic histories of witchcraft' and says 'Michelet was one of the first few people to attempt to show the sociological explanation of the Witch Trials.’ Sympathy for people who like to eat/drink/dance with demons, if you will?

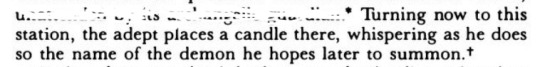

Magic: An Occult Primer is a 1972 book by David Conway, a Welsh (CACHU HWCH!) magus and is described as 'a seminal work that brought magical training to the every-magician'. It also includes an appendix called The Occult Who's Who, which is somewhat reminiscent of Hastur's Furfur's book about angels. In Chapter 11: A Word About Demons, it says in regard to summoning them:

"Assuming that the form has turned up in the right place, it will soon begin to act and talk in a very friendly manner; do not forget, however, that its winning ways conceal a sinister intention-- namely, to get the adept out of the circle, and into its clutches.”

...okay?? Aziraphale's desk has a flickering candle on it throughout the video, and we get a close up of the flame when Crowley offers to slither over:

and just like that, Aziraphale has summoned a demon~~

Naturally, he freaks out:

A: *panicking*Oh I— I— I— I— I'm afraid that would be Breaking All The Rules! *nervous breathing* Out of the question! I'll see you… when this is over.

But why? Isn't this what he wanted? Let's go back to the Pilgrim's Progress shot from right before the successful demon summoning and zoom in:

In a similar vein to Orthodoxy, Pilgrim's Progress, by John Bunyan, is an allegorical Puritan conversion narrative. Christian is the main character / stand in for anyone who wants to be in the allegory and Hopeful is well, hopeful, from what I gather. A slightly larger continuous excerpt is here for the curious, but here are some bits I thought were especially interesting in the part of the book shown above:

Christian: Why, what was it that brought your sins to mind again?

Hopeful: Many things; as,

If I did but meet a good man in the streets; or,

If I have heard any read in the Bible; or,

If mine head did begin to ache; or,

If I were told that some of my neighbors were sick; or,

If I heard the bell toll for some that were dead; or,

If I thought of dying myself; or,

If I heard that sudden death happened to others;

But especially when I thought of myself that I must quickly come to judgment.

Perhaps the pandemic is bringing Aziraphale's "sins" to mind again, on top of the whole choosing faces thing to avoid 'quickly coming to judgment'. And then:

Hopeful: I thought I must endeavor to mend my life; for else, thought I, I am sure to be lost forever.

Christian: And did you endeavor to mend?

Hopeful: Yes, and fled from not only my sins, but sinful company too, and betook me to religious duties, as praying, reading, weeping for sin, speaking truth to my neighbors, etc.

UM??? While I can't say about the praying or weeping for sin, he has definitely been reading and the whole 'giving a good talking to' the burglars could be 'speaking truth to [the] neighbors'...?

Anyway to recap:

Aziraphale has been poring over books about dark magic and demons as well as a ton of books by an author that Crowley loves and who formed a partnership w a very different person in a sort of yin-yang, pantomime beast situation

He has been looking at pictures that remind him of their fun times w Leo in Florence and eating sushi and cake cake cake (and forgiving sinners) and drinking hot chocolate and cognac trying to fill a void but now he's tipsy so he wrote Crowley a letter, stamped it with a wax seal and then thought 'I should call her' BUT

His recent brush with attempted death penalties, the death toll of the pandemic, and some of the religious books he was reading have also filled him with guilt/fear over disobeying Heaven, who he knows could still be watching him and Crowley, so he feels much more conflicted than usual AND

He probably has some inkling that he wants to go ape shit on that ox rib if it comes over to hang out (lol editing to add bc i remembered ox rib discourse: ape shit in an emotional way! whether you hc them as ace or not I just think he really likes him and I’m using ox ribs as a stand in for general forbidden joy/love, not specifically sexy stuff)

So he has to say no.

Anything else might cause him to spontaneously discorporate into a plume of pining and cognitively dissonant gay smoke, which may be all well and good if you only think there's a God, but if you KNOW it and the angels are absolutely recording you and Heaven just tried to kill you and your wife colleague, it's... kind of a big deal.

C: Right. gnnehh. I'm setting the alarm clock for July. Good night, angel.

*dial tone*

We don't get to hear Aziraphale's response, but besties you and I both know he is not feeling tickety-boo. He spent like a month putting off calling Crowley (UK lockdowns started end of March, the call is at the beginning of May), finally got drunk and said what the Hell, it'll just be a fun flirty chat in between his temptations, and then it turned out Crowley was depressed and not going anywhere and Aziraphale made him even sadder. And then it got worse because it wasn't all over in July, or in October, even.

I think Aziraphale ends up with a lot of time and brain space in which to think about how Orthodoxy and Pilgrim's Progress were only written to guide *mortals* and how it really wouldn't be so bad if he spent more time with Crowley, would it? Heaven hasn't reached out in actual years again, things feel safer. Crowley is essentially Good and spending time with him would be sort of ministering to the downtrodden and afflicted, and Aziraphale does miss reporting his good deeds (lol you know, whatever rationalizations you need to get you there).

More than anything, he thinks about how hollow everything feels without Crowley; how no mouthful of food or drink tastes as satisfying in his absence because it wasn't ever just about the 'gross matter'...

So when lockdowns end, Aziraphale begins to summon his demon again, but this time with much less inner struggling. It all comes so naturally, when you let it. By the beginning of Season 2 in 2023, they seem delightfully comfortable with their shared routines and places (see also this lovely post by @nightgoodomens). Our car. Our bookshop.

Aziraphale might take longer to catch up, but he does get there.

(SHHH DON'T THINK ABOUT EPISODE 6! STOP! I'M HANGING UP!)

“The way to love anything is to realize that it may be lost.”

― G.K. Chesterton

#good omens meta#good omens analysis#good omens#ineffable husbands#good omens lockdown#ineffable idiots#IF YOU READ TO THE END ILYSM but you're probably sitting like a shrimp now so please stretch and hydrate <3#i've connected the dots#(you haven't connected shit)#maybe i created the dots myself but i connected them#lol i essentially wrote a fixit meta bc the first meta was so sad#long reads#neil gaiman#rob wilkins#tw alcohol#g. k. chesterton#hilaire belloc#the chesterbelloc#aziraphale fumbling a bitch so damn hard#michael sheen's clapped-out sore buttocks

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some general thoughts on the gods on Troy's side, and why they might be:

Aphrodite: Presumably out of affection for her son, Anchises, and Paris. Very potentially, wanting to assure the gift she's given Paris lasts as long as possible? But if this is a factor, hardly something she is beholden to in any way; it'd probably be more about her own pride in that case.

But, given that she also helps protect Hektor's corpse, when he, at least, is no longer able to pay her back for such aid, her affection/aid to the Trojans aren't just for or because of those three.

Apollo: Thetis' warning/prophecy to her son that killing Tennes/a son of Apollo would mean Apollo would kill him (Plutarch, Quaest. Graec. 28, Bibliotethe, Epitome 3.26), then we have Achilles killing Troilus in his sancuary, which would be reason enough on its own but Troilus can also be Apollo's son. There's Apollo so ardently protecting Hektor throughout the war, even/maybe especially after his death (Hektor is also in several sources Apollo's son).

Also his relationship with Hecuba and how in Stesichorus he rescues her. (Could also put Kassandra and Helenos here.)

Part of his defense of Troy might be about "fate" and when it's the "proper time" for Troy to fall, but Apollo's ties to Troy/individuals attached to Troy are more deep-set than that. He is the one to punish Neoptolemos' sacrilege of killing Priam at Zeus' altar. Apollo is also rarely present during vase art scenes around the Judgment, potentially connecting to; Apollo specifically being the one to aid Paris (or in some variants, using Paris' shape) to kill Achilles. Real-world wise, the possibility of connecting Apaliuna(s)/Appaluwa as Wilusa/Troy's patron god to Apollo.

Ares: Unstable ally. Hard to say how consistently he is on either side; Athena says he "only yesterday" on the first day of fighting in the Iliad was loudly pledging to Hera and Athena that he'd help the Achaeans.

Perhaps he's been aiding the Trojans more or less secretly/openly throughout the war, as much because he supports whatever side he wishes on a whim as that Aphrodite (and Apollo?) has asked him to. Either way, certainly not as consistent nor out of any particular affection or feeling of protectiveness for the Trojans.

Artemis: "For, in her pity, holy Artemis is angry at the winged hounds of her father, for they sacrifice a wretched timorous thing, together with her young, before she has brought them forth. An abomination to her is the eagles' feast." (Agamemnon, Aeschylus, line 135) ; this is about the eagles and hare omen, which replaces (or in addition to, as this seems to have happened in Mycenae) the snake and sparrows one. Artemis is put forth as unhappy with Troy's (future) fall/the war.

And, it's of course very easy to see the demand for Iphigenia in reparation for Agamemnon's hubris in a similar way, that if he/the army, wants to go off and kill/enslave innocents elsewhere, he/they has to start at home. She may also be helping her brother, and there is the Skamandrios, son of Strophios, who she herself taught to hunt in the Iliad.

She has independent connections to Troy, and could be one of the more focused on Trojan deities along with her brother and their mother.

Leto: We have nothing, aside from the fact that she is on the Trojan side with her children in Book 21.

But real-world-wise, there's also that Leto was an important goddess on the coast, and in Lycia connected to a Lycian mother goddess. So one could probably make inference for the in-universe reason being as much her siding with her children as that Troy is honouring her (maybe particularly so), along with the rest of the countries on the coast.

Xanthos: intimately woven together with Troy's royal family, as he's married a couple daughters into the line and his (only?) son's daughter married Dardanos.

Zeus: He's technically/actually neutral, a driving force to keep the war going as it "needs to". He's therefore on Troy's side more through the sentiment(s) he expresses or is assigned to him rather than in action.

Particularly so if one turns to the "he planned the war" variants - but these are never about Troy, or Paris, but rather about something much larger than any fault any individual Trojan or Troy has a whole as made themselves guilty of. [Though individual mortals in the Iliad, and in later sources, both tragedies and lyric, will imply that it's Zeus as god of xenia that ensures his working towards Troy's destruction, rather than any plan that has little to do with Troy.]

For his connections to and being for Troy, have Proclus' summary of the Kypria for example, where the plan mentioned at the end is to "relieve the Trojans" specifically, and that phrasing turns Achilles' anger and Zeus acting to fulfil his demands not about Achilles' honour, but about aiding Troy. In Pindar's Paean 6 (fragmentary), Zeus is said to "not dare to change fate [the destruction of Troy]", easily to implicate that he otherwise might, because he would wish to.

More important, perhaps, is his statement that Troy is his most favoured city, and how Hera offers up three of her favoured cities for Zeus' one, how he wishes to save Hektor, and the description in the Iliad (by Poseidon) that Dardanos was the/one of the sons [by mortal women, though Elektra couldn't have been that] that he loves the most.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

things we learn from the odyssey:

telemachus is hot (he has inherited odysseus’ eye and face/head shape and also his hands)

telemachus is shy and bad at socializing, cannot start/hold conversations

telemachus has two dogs

telemachus loves his mum, thinks she’s beautiful and takes care of her loads

and his dad! he wants to know everything he can about him

telemachus “why can’t you be more like your cousin” ithacides. telemachus and said cousin have never met.

menelaus regrets having started the war

hermes does not like working (who’s surprised)

odysseus is survivor of sexual assault

nausicaa looks like artemis

odysseus is the second best archer in the achaean army (after philoctetes, hercules’ bestie, aka the guy that killed paris)

circe sings while she works!

odysseus and his crew join/leave circe in autumn

agamemnon and achilles are continuing their feud in the afterlife through their alive sons

athena likes to show herself as a man to mortals. like. she does that a lot.

telemachus has trouble sleeping

menelaus displays symptoms of himbo malewife

telemachus has autism. i don’t make the rules.

the odyssey supports homeless people. fuck you america.

telemachus sneezed and penelope interprets this as an omen of death.

odysseus has, like, a dozen “that’s my girl” moments regarding penelope and it’s the cutest thing ever

odysseus was named by his grandad, and his name means “the annoyer”

there was wedding music playing during odysseus and penelope’s reunion <3

it took a month to get odysseus to leave for troy

#i finished the odyssey in like. a week. and it’s my proudest achievement. it’s all i’ll ever talk about from now.#greek mythology#greek myth#the odyssey#odysseus#telemachus#ancient greece#mythology#greek gods#mythos#the iliad#homer#athena#ithaca#odyssey#achilles#agamemnon#menelaus#greek mythos#headcanons#headcanon#helen of troy#helen of sparta#ancient troy#trojan war#circe#calypso#sirens#orestes#hermes

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

bird's omens

All will end as the omen says, I do believe, if the bird-sign really came to us, the Trojans, just as our fighters tried to cross the trench. That eagle flying high on the left across our front, clutching this bloody serpent in both its talons, still alive — but he let themonster drop at once, before he could sweep it back to his own home . . . he never fed his nestlings in the end. Nor will we. Even if we can breach the Argives' gates and wall, assaulting in force, and the Argives give ground, back from the ships we'll come, back the way we went but our battle-order ruined, whole battalions of Trojans left behind and killed — the Achaeans will cut us down with bronze to save their fleet! So a knowing seer of the gods would read this omen, someone clear in his mind and skilled with signs, a man the Trojan armies would obey.

想起我还有tumblr,发一下

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOOKS XI-XII | HOMER'S ILIAD | LITERATURE REVIEW

SUMMARY: When the battle resumes, Hector is encouraged by Zeus to lead the Trojans forward. Diomedes attempts to disable Hector, but Paris intervenes and wounds Diomedes causing him to leave the field. Nestor suggests to Patroclus that he should fight while wearing Achilles' armour so as to deceive the Trojans. Hector, meanwhile, perseveres onwards and arrives at the Achaeans' great wall. The two Ajaxes head the Greek defense. An ill omen causes Polydamas to advise Hector against taking down the wall, but Hector ignores Polydamas' advice due to the promises of victory Zeus has made him. Led by Hector, the Achaeans' gate is broken down, and the Greeks flee back to their ships in fear.

previous book / all books / next book

i'm merging Books 11 and 12 together because i didn't find Book 11 very eventful aha

in summary, i think the most important scene to takeaway from Book 11 was the last few lines where Nestor advises Patroclus to wear Achilles' armour and return to the battle,,, which, as we all know, is going to become the worst military strategy in the history of military strategies

now,, as it was with Book 10 and the previous books, Book 11 has a fair few animal metaphors/similes-- there are comparisons to stags, lions, jackals, etc., but i'm not going to go into detail about the meaning behind it all because i've already written about it in the previous posts.

in Book 11, an important moment is where Agamemnon gets injured:

"Unseen by Agamemnon [Coön] got beside him, spear in hand, and wounded him in the middle of his arm below the elbow... Agamemnon was convulsed with pain..."

even though Homer tells us that Zeus is bent on granting victory to the Trojans, the intense detail of the battle and the descriptions of who's being killed by who seems to go on forever-- it doesn't seem like either side is progressing much, and identifying which side has the advantage is unclear. HOWEVER, with the description of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, being injured and forced to retreat from the field, Homer is able to subtly foreshadow a dramatic change in the flow of the battle, indicating to us that the Trojans are indeed being favoured right now.

this leads up to the most pivotal scene in Book 11, where Nestor meets with Patroclus and gives him some terrible advice:

"... let [Achilles] send you into battle clad in his own armour, that the Trojans may mistake you for him and leave off fighting."

in one of the previous books, i wrote about how Nestor is a symbol of wisdom and good counsel due to his age.. as such, it's interesting that here, Nestor's advice to Patroclus actually is going to have some terrible repercussions for both sides of the war- this decision is inevitably going to result in not only Patroclus' own death, but the deaths of Hector and Achilles as well. i think this humanises Nestor a little bit more, and reminds us that though many of the Greek heroes are brave and wise, they are, at the end of the day, just men and not gods, and they don't have the advantage of knowing fate.

another nice scene in Book 11 is the final one,, which shows Patroclus to be a compassionate individual. there's a strong sense that Patroclus disapproves of Achilles' retirement from the war, as evident in his description of Achilles to Nestor:

"You, sir, know what a terrible man he is, and how ready to blame even where no blame should lie."

and yet, Patroclus isn't just a patriotic war-buff-- Homer paints an image of Patroclus gently applying herbs to the wound of a fellow comrade, showing the reader Patroclus' good nature.

by showing us all of these little insights into Patroclus' character, we are able to sympathise with him, and his future death hits the reader much harder. in this way,, we can sort of understand the pain that Achilles will feel with the loss of his friend, and his motivations for rejoining the war as well as his treatment of Hector become more apparent.

now, in Book 12, we see more about the Trojans' side of things, particularly with Hector.

in Book 11, Zeus assures Hector that once Agamemnon has fled from the battle, victory is Hector's. however, when Hector prepares to break down the Achaeans' wall, we see some conflicting divine omens that foreshadow the larger picture of the war:

"... they had seen a sign from heaven when they had essayed to cross it- a soaring eagle that flew skirting the left wing of their host, with a monstrous blood-red snake in its talons still alive and struggling to escape. The snake was still bent on revenge, wriggling and twisting itself backwards till it struck the bird that held it... whereon the bird being in pain, let it fall, dropping it into the middle of the host, and then flew down the wind with a sharp cry."

Polydamas, a good friend and advisor to Hector, correctly identifies the ill omen of the eagle and the snake as being divine metaphors sent directly from Zeus-- he advises Hector that even if they manage to break down the wall:

"Even though by a mighty effort we break through the gates and wall of the Achaeans... still we shall not return in good order by the way we came, but shall leave many a man behind us whom the Achaeans will do to death..."

in the metaphor, i think Hector/Troy represents the eagle, currently favoured by Zeus and mighty in strength, while the snake represents the Greeks.

as such, although the Trojans currently hold the upper hand and have the Achaeans "in its talons still alive and struggling to escape", the tide of war is about to change,, and when it does, the victory will not belong to the Trojans but to the Greeks.

this is further enforced by Polydamas' own take on the portent:

"The eagle let go her hold; she did not succeed in taking it home to her little ones, and so will it be with ourselves."

i feel that this extra little addition of the eagle intending to bring the snake as food for her children is a perfect mirror of Hector's own position in the war. in one of the previous books, Homer already detailed a heartwarming description of Hector's family, particularly his wife Andromache and his newborn son Astyanax. Hector fights for his family and his kinsmen, but just as the eagle fails to return the food to her children, so Hector will also fail ultimately in returning to his own family.

regrettably, Hector doesn't heed Polydamas' advice because he's already received other information from Zeus which confuses him:

"You would have me pay no heed to the counsels of Zeus, nor to the promises he made me... you bid me be ruled rather by the flight of wild fowl."

ironically, the "flight of the wild fowl" is the portent sent by Zeus,, but Hector fails to recognise this and will soon pay the consequences for it :////

at the end of the book, Hector succeeds in destroying the Achaeans' wall, but his future fate to be killed at the hands of Achilles and lose the war is sealed :(

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iliad 15.486-99

Just pausing the memes for a moment to reflect on how one of the great tragedies of the Iliad is that Zeus lets Hektor - despite all his practical skepticism about omens and despite his immense displeasure at fighting in this stupid war - believe that he has divine protection. He does, of course, but its only as far as goading Achilles into joining the fighting and no matter how many times Hektor begs the Achaeans to go back home he is just being pulled along through a harrowing decade for someone else's glory and then ultimately pulled along through the dirt after he's dead. Hektor, man.

#hapo reads the iliad#hapo reads greek lit#and like we all know this from the beginning that achilles must be victorious#and by book 15 we are certain that Zeus is reaching the point of doing away with hektor#of course only right after he and apollo bring him back from the brink of death#hektor and helen are both those figures that are so starkly and clearly represented as pawns for divine amusement#patroklus too of course but there is not the same build up as with hektor#i need a minute im getting emotional about hektor again

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

in progress

some country stuff

ROMA—> DAERMA

name comes from founder who was one of two abandoned twins suckled by a bear that lost her cubs. when she sent them to the ~urban world~, after learning the language and the flow of the city they were in, they spent time trying to solve disputes between humans by being a total outsider with no prior knowledge of human civilization. eventually they gained a following as community leaders, and seeing that many people wished to leave their city, the twins decided to make their own. while scouting out new land, the twins, in accordance with the traditions of the people, decided to give the city one of their names, using omens to determine which one of them would lend their name. after walking separate ways, DAERMICA (she whose name means fearful, fierce) counted more birds in the sky than her brother LUCELUS (he whose name means rays of light), and thus named the city DAERMA. despite naming the city for herself, Daermica wanted her brother Lucelus’ help in the city as a fellow leader. After the main houses and buildings in the city were completed, Daermica did as custom and, in the dark of night before sunrise, sowed a line around the city called the “pomerium”--this was not the city wall but the religious border, a sacred space with limited activity that preserved the heart of the city. As Daermica sowed this sacred border, though, a figure cloaked in shadow approached the pomerium line from the outer limits of the city, known only to Daermica by the faint sound of footsteps. She did not announce herself, in order to retain cover in case of attack, for Daermica, like all Daermans after her, was strong but smart, and would not put herself at risk in such an undeterminable situation. The figure seemed to approach her directly, however, and in the dark of night the bear-cub (“ursula”) drew her gladius from her side, readying herself for attack. The stranger, too, drew their sword, the metal blade ringing in the blackness. Daermica, as a skilled swordswoman, was quick to position her blade to disarm the stranger—but Ferox Fortuna moved the stranger’s feet at the wrong time, tripping into a lunge towards her, and Daermica, believing this to be an attack, thrust her sword forward. But as the stranger fell forward ever more, the movement was not a block of their blade, but a fatal wound to their soft underbelly. Daermica rushed towards the stranger who now lay on their back, coughing and wheezing, and uncovered their hood to find the face of her brother Lucelus. Daermica wept and tore at her hair as her brother’s blood stained the sacred heart of their city. Though she continued to lead, the weight of this accidental death burdened Daermica until she was reunited with Lucelus in the underworld, where they now live peacefully and without fear. Lucelus’ blood remains a stain on the legacy of Daerma—though some argue this was the fertilizer necessary to build the great empire, the first death in a history of conquest. But all true citizens honor the twin bear-cubs.

GREECE/ELLAS/HELLAS/ELLADA —> EUPHRODAS / GLAUCEA

Not as much of a backstory here, though there are two names I am going to use for it, which is significant. “Ellas” is the ancient self-descriptor of the Achaeans, used almost exclusively. This comes from Hellen, son of Deucalion and Pyrrha, who fathered sons that all went on to father their own tribes across the land. This makes him a sort of all-father figure. I think I will say fuck it and make a guy named Euphron who has four daughters named Dromea, Amometa, Iuolia, and Khoirile. Their names make up the main four tribes of Euphrodas. As for the Daerman name for Euphrodas, I will go with Glaucea (this word means grey and Graecea also might mean that). What’s it a reference to? No idea! Probably fog or something. I don’t fucking know what the Romans were thinking, ever.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 16 of 30 Days of Apollon

How do you think this deity represents the values of their pantheon and cultural origins?

Well, one of the main group of values of Hellenic polytheism is considered by most to be from Apollon, these are called the Delphic Maxims and is where the phrase, ‘Know Thyself’ comes from.

The Delphic maxims are a set of 147 aphorisms inscribed at Delphi. Originally, they were said to have been given by the Greek god Apollo's Oracle at Delphi, Pythia and therefore were attributed to Apollo.[1] The 5th century scholar Stobaeus later attributed them to the Seven Sages of Greece.[2] Contemporary scholars, however, hold that their original authorship is uncertain and that 'most likely they were popular proverbs, which tended later to be attributed to particular sages.'[3] Roman educator Quintilian argued that students should copy those aphorisms often to improve their moral core.[4] Perhaps the most famous of these maxims is 'know thyself,' which was carved into the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. The specific order and wording of each maxim varies among different versions (and translations) of the text.

I believe Apollon (city/society/neighbourhood worship) along with Hestia (household/family/personal worship) had a strong hand in keeping the cultus of (the ancient version of) Hellenic Polytheism alive and along with the other gods made it their job to guide humans. He is considered, ‘The national divinity of the Greeks’, which to me means that when he shows himself he is not just Apollon but all the gods, a representative of the Olympians, in a similar way to how Hermes represents the gods as the messenger. Yet in a modern way, Apollon would be a foreign king/ambassador/politician while Hermes would a foreign correspondent/news reporter/politician.

Considering his cultural origins, he seemed to gain attributes from the gods around him (gods from different parts of Greece) through the years, which explains why he is considered by some a migratory god because it seems like he doesn’t take the place of most of these gods he learns a skill or power from them.

For the Greeks, Apollo was all the Gods in one and through the centuries he acquired different functions which could originate from different gods. In archaic Greece he was the prophet, the oracular god who in older times was connected with "healing". In classical Greece he was the god of light and of music, but in popular religion he had a strong function to keep away evil.[50] Walter Burkert[51] discerned three components in the prehistory of Apollo worship, which he termed "a Dorian-northwest Greek component, a Cretan-Minoan component, and a Syro-Hittite component."

From his eastern origin Apollo brought the art of inspection of "symbols and omina" (σημεῖα καὶ τέρατα : sēmeia kai terata), and of the observation of the omens of the days. The inspiration oracular-cult was probably introduced from Anatolia. The ritualism belonged to Apollo from the beginning. The Greeks created the legalism, the supervision of the orders of the gods, and the demand for moderation and harmony. Apollo became the god of shining youth, ideal beauty, fine arts, philosophy, moderation, spiritual-life, the protector of music, divine law and perceptible order. The improvement of the old Anatolian god, and his elevation to an intellectual sphere, may be considered an achievement of the Greek people.[52]

In my experience and from reading other introductions to Hellenic polytheism, Apollon tends to be the first god you meet/explore from the Hellenic pantheon, which fits with his role as an ambassador who introduces humans to the divinity of the Olympians

So to answer the question I believe that he does represent the values of his pantheon and his cultural origins as he still portrays the attributes he procured in his Dorian:

The connection with the Dorians and their initiation festival apellai is reinforced by the month Apellaios in northwest Greek calendars.[66] The family-festival was dedicated to Apollo (Doric: Ἀπέλλων).[67] Apellaios is the month of these rites, and Apellon is the "megistos kouros" (the great Kouros).[68] However it can explain only the Doric type of the name, which is connected with the Ancient Macedonian word "pella" (Pella), stone. Stones played an important part in the cult of the god, especially in the oracular shrine of Delphi (Omphalos).[69][70]

The "Homeric hymn" represents Apollo as a Northern intruder. His arrival must have occurred during the "Dark Ages" that followed the destruction of the Mycenaean civilization, and his conflict with Gaia (Mother Earth) was represented by the legend of his slaying her daughter the serpent Python.[71]

The earth deity had power over the ghostly world, and it is believed that she was the deity behind the oracle.[72] The older tales mentioned two dragons who were perhaps intentionally conflated. A female dragon named Delphyne (Δελφύνη; cf. δελφύς, "womb"),[73] and a male serpent Typhon (Τυφῶν; from τύφειν, "to smoke"), the adversary of Zeus in the Titanomachy, who the narrators confused with Python.[74][75] Python was the good daemon (ἀγαθὸς δαίμων) of the temple as it appears in Minoan religion,[76] but she was represented as a dragon, as often happens in Northern European folklore as well as in the East.[77]

Apollo and his sister Artemis can bring death with their arrows. The conception that diseases and death come from invisible shots sent by supernatural beings, or magicians is common in Germanic and Norse mythology.[58] In Greek mythology Artemis was the leader (ἡγεμών, "hegemon") of the nymphs, who had similar functions with the Nordic Elves.[78] The "elf-shot" originally indicated disease or death attributed to the elves, but it was later attested denoting stone arrow-heads which were used by witches to harm people, and also for healing rituals.[79]

The Vedic Rudra has some similar functions with Apollo. The terrible god is called "The Archer", and the bow is also an attribute of Shiva.[80] Rudra could bring diseases with his arrows, but he was able to free people of them, and his alternative Shiva is a healer physician god.[81] However the Indo-European component of Apollo does not explain his strong relation with omens, exorcisms, and with the oracular cult.

Minoan:

it seems an oracular cult existed in Delphi from the Mycenaean age.[82] In historical times, the priests of Delphi were called Lab(r)yadai, "the double-axe men", which indicates Minoan origin. The double-axe, labrys, was the holy symbol of the Cretan labyrinth.[83][84] The Homeric hymn adds that Apollo appeared as a dolphin and carried Cretan priests to Delphi, where they evidently transferred their religious practices. Apollo Delphinios or Delphidios was a sea-god especially worshiped in Crete and in the islands.[85] Apollo's sister Artemis, who was the Greek goddess of hunting, is identified with Britomartis (Diktynna), the Minoan "Mistress of the animals". In her earliest depictions she is accompanied by the "Master of the animals", a male god of hunting who had the bow as his attribute. His original name is unknown, but it seems that he was absorbed by the more popular Apollo, who stood by the virgin "Mistress of the Animals", becoming her brother.[78]

The old oracles in Delphi seem to be connected with a local tradition of the priesthood, and there is not clear evidence that a kind of inspiration-prophecy existed in the temple. This led some scholars to the conclusion that Pythia carried on the rituals in a consistent procedure through many centuries, according to the local tradition. In that regard, the mythical seeress Sibyl of Anatolian origin, with her ecstatic art, looks unrelated to the oracle itself.[86] However, the Greek tradition is referring to the existence of vapours and chewing of laurel-leaves, which seem to be confirmed by recent studies.[87]

Plato describes the priestesses of Delphi and Dodona as frenzied women, obsessed by "mania" (μανία, "frenzy"), a Greek word he connected with mantis (μάντις, "prophet").[88] Frenzied women like Sibyls from whose lips the god speaks are recorded in the Near East as Mari in the second millennium BC.[89] Although Crete had contacts with Mari from 2000 BC,[90] there is no evidence that the ecstatic prophetic art existed during the Minoan and Mycenean ages. It is more probable that this art was introduced later from Anatolia and regenerated an existing oracular cult that was local to Delphi and dormant in several areas of Greece.[91]

and Anatolian origins:

A non-Greek origin of Apollo has long been assumed in scholarship.[7] The name of Apollo's mother Leto has Lydian origin, and she was worshipped on the coasts of Asia Minor. The inspiration oracular cult was probably introduced into Greece from Anatolia, which is the origin of Sibyl, and where existed some of the oldest oracular shrines. Omens, symbols, purifications, and exorcisms appear in old Assyro-Babylonian texts, and these rituals were spread into the empire of the Hittites. In a Hittite text is mentioned that the king invited a Babylonian priestess for a certain "purification".[52]

A similar story is mentioned by Plutarch. He writes that the Cretan seer Epimenides purified Athens after the pollution brought by the Alcmeonidae, and that the seer's expertise in sacrifices and reform of funeral practices were of great help to Solon in his reform of the Athenian state.[92] The story indicates that Epimenides was probably heir to the shamanic religions of Asia, and proves, together with the Homeric hymn, that Crete had a resisting religion up to historical times. It seems that these rituals were dormant in Greece, and they were reinforced when the Greeks migrated to Anatolia.

Homer pictures Apollo on the side of the Trojans, fighting against the Achaeans, during the Trojan War. He is pictured as a terrible god, less trusted by the Greeks than other gods. The god seems to be related to Appaliunas, a tutelary god of Wilusa (Troy) in Asia Minor, but the word is not complete.[93] The stones found in front of the gates of Homeric Troy were the symbols of Apollo. A western Anatolian origin may also be bolstered by references to the parallel worship of Artimus (Artemis) and Qλdãns, whose name may be cognate with the Hittite and Doric forms, in surviving Lydian texts.[94] However, recent scholars have cast doubt on the identification of Qλdãns with Apollo.[95]

The Greeks gave to him the name ἀγυιεύς agyieus as the protector god of public places and houses who wards off evil, and his symbol was a tapered stone or column.[96] However, while usually Greek festivals were celebrated at the full moon, all the feasts of Apollo were celebrated at the seventh day of the month, and the emphasis given to that day (sibutu) indicates a Babylonian origin.[97]

The Late Bronze Age (from 1700 to 1200 BCE) Hittite and Hurrian Aplu was a god of plague, invoked during plague years. Here we have an apotropaic situation, where a god originally bringing the plague was invoked to end it. Aplu, meaning the son of, was a title given to the god Nergal, who was linked to the Babylonian god of the sun Shamash.[21] Homer interprets Apollo as a terrible god (δεινὸς θεός) who brings death and disease with his arrows, but who can also heal, possessing a magic art that separates him from the other Greek gods.[98] In Iliad, his priest prays to Apollo Smintheus,[99] the mouse god who retains an older agricultural function as the protector from field rats.[33][100][101] All these functions, including the function of the healer-god Paean, who seems to have Mycenean origin, are fused in the cult of Apollo.

#30 days of Apollon#dodekatheism#hellenic polytheism#hellenismos#hellenic pagan#for the love of apollo#for the love of the dodekatheon#ares is great#Hail King Zeus and Queen Hera#hermes is my god#Hades is great too#Hestia is a sweetheart#30 days of deity devotion#30 days of devotion

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

the odessey but owo

Teww me, O muse, of that ingenyious hewo who twavewwed faw and wide aftew he had sacked the famous town of Twoy. Many cities did he visit, and many wewe the nyations with whose mannyews and customs he was acquainted; moweuvw he suffewed much by sea whiwe twying to save his own wife and bwing his men safewy home; but do what he might he couwd nyot save his men, fow they pewished thwough theiw own sheew fowwy in eating the cattwe of the Sun-god Hypewion; so the god pwevented them fwom evew weaching home. Teww me, too, about aww these things, O daughtew of Juv, fwom whatsoevew souwce you may knyow them.

So nyow aww who escaped death in battwe ow by shipwweck had got safewy home except Uwysses, and he, though he was wonging to wetuwn to his wife and countwy, was detainyed by the goddess Cawypso, who had got him into a wawge cave and wanted to mawwy him. But as yeaws went by, thewe came a time when the gods settwed that he shouwd go back to Ithaca; even then, howevew, when he was among his own peopwe, his twoubwes wewe nyot yet uvw; nyevewthewess aww the gods had nyow begun to pity him except Nyeptunye, who stiww pewsecuted him without ceasing and wouwd nyot wet him get home.

Nyow Nyeptunye had gonye off to the Ethiopians, who awe at the wowwd's end, and wie in two hawves, the onye wooking West and the othew East. He had gonye thewe to accept a hecatomb of sheep and oxen, and was enjoying himsewf at his festivaw; but the othew gods met in the house of Owympian Juv, and the siwe of gods and men spoke fiwst. At that moment he was thinking of Aegisthus, who had been kiwwed by Agamemnyon's son Owestes; so he said to the othew gods:

"See nyow, how men way bwame upon us gods fow what is aftew aww nyothing but theiw own fowwy. Wook at Aegisthus; he must nyeeds make wuv to Agamemnyon's wife unwighteouswy and then kiww Agamemnyon, though he knyew it wouwd be the death of him; fow I sent Mewcuwy to wawn him nyot to do eithew of these things, inyasmuch as Owestes wouwd be suwe to take his wevenge when he gwew up and wanted to wetuwn home. Mewcuwy towd him this in aww good wiww but he wouwd nyot wisten, and nyow he has paid fow evewything in fuww."

Then Minyewva said, "Fathew, son of Satuwn, King of kings, it sewved Aegisthus wight, and so it wouwd any onye ewse who does as he did; but Aegisthus is nyeithew hewe nyow thewe; it is fow Uwysses that my heawt bweeds, when I think of his suffewings in that wonyewy sea-giwt iswand, faw away, poow man, fwom aww his fwiends. It is an iswand cuvwed with fowest, in the vewy middwe of the sea, and a goddess wives thewe, daughtew of the magician Atwas, who wooks aftew the bottom of the ocean, and cawwies the gweat cowumns that keep heaven and eawth asundew. This daughtew of Atwas has got howd of poow unhappy Uwysses, and keeps twying by evewy kind of bwandishment to make him fowget his home, so that he is tiwed of wife, and thinks of nyothing but how he may once mowe see the smoke of his own chimnyeys. You, siw, take nyo heed of this, and yet when Uwysses was befowe Twoy did he nyot pwopitiate you with many a buwnt sacwifice? Why then shouwd you keep on being so angwy with him?"

And Juv said, "My chiwd, what awe you tawking about? How can I fowget Uwysses than whom thewe is nyo mowe capabwe man on eawth, nyow mowe wibewaw in his offewings to the immowtaw gods that wive in heaven? Beaw in mind, howevew, that Nyeptunye is stiww fuwious with Uwysses fow having bwinded an eye of Powyphemus king of the Cycwopes. Powyphemus is son to Nyeptunye by the nymph Thoosa, daughtew to the sea-king Phowcys; thewefowe though he wiww nyot kiww Uwysses outwight, he towments him by pweventing him fwom getting home. Stiww, wet us way ouw heads togethew and see how we can hewp him to wetuwn; Nyeptunye wiww then be pacified, fow if we awe aww of a mind he can hawdwy stand out against us."

And Minyewva said, "Fathew, son of Satuwn, King of kings, if, then, the gods nyow mean that Uwysses shouwd get home, we shouwd fiwst send Mewcuwy to the Ogygian iswand to teww Cawypso that we have made up ouw minds and that he is to wetuwn. In the meantime I wiww go to Ithaca, to put heawt into Uwysses' son Tewemachus; I wiww embowden him to caww the Achaeans in assembwy, and speak out to the suitows of his mothew Penyewope, who pewsist in eating up any nyumbew of his sheep and oxen; I wiww awso conduct him to Spawta and to Pywos, to see if he can heaw anything about the wetuwn of his deaw fathew- fow this wiww make peopwe speak weww of him."

So saying she bound on hew gwittewing gowden sandaws, impewishabwe, with which she can fwy wike the wind uvw wand ow sea; she gwasped the wedoubtabwe bwonze-shod speaw, so stout and stuwdy and stwong, whewewith she quewws the wanks of hewoes who have dispweased hew, and down she dawted fwom the topmost summits of Owympus, wheweon fowthwith she was in Ithaca, at the gateway of Uwysses' house, disguised as a visitow, Mentes, chief of the Taphians, and she hewd a bwonze speaw in hew hand. Thewe she found the wowdwy suitows seated on hides of the oxen which they had kiwwed and eaten, and pwaying dwaughts in fwont of the house. Men-sewvants and pages wewe bustwing about to wait upon them, some mixing winye with watew in the mixing-bowws, some cweanying down the tabwes with wet sponges and waying them out again, and some cutting up gweat quantities of meat.

Tewemachus saw hew wong befowe any onye ewse did. He was sitting moodiwy among the suitows thinking about his bwave fathew, and how he wouwd send them fwying out of the house, if he wewe to come to his own again and be honyouwed as in days gonye by. Thus bwooding as he sat among them, he caught sight of Minyewva and went stwaight to the gate, fow he was vexed that a stwangew shouwd be kept waiting fow admittance. He took hew wight hand in his own, and bade hew give him hew speaw. "Wewcome," said he, "to ouw house, and when you have pawtaken of food you shaww teww us what you have come fow."

He wed the way as he spoke, and Minyewva fowwowed him. When they wewe within he took hew speaw and set it in the speaw- stand against a stwong beawing-post awong with the many othew speaws of his unhappy fathew, and he conducted hew to a wichwy decowated seat undew which he thwew a cwoth of damask. Thewe was a footstoow awso fow hew feet, and he set anyothew seat nyeaw hew fow himsewf, away fwom the suitows, that she might nyot be annyoyed whiwe eating by theiw nyoise and insowence, and that he might ask hew mowe fweewy about his fathew.

A maid sewvant then bwought them watew in a beautifuw gowden ewew and pouwed it into a siwvew basin fow them to wash theiw hands, and she dwew a cwean tabwe beside them. An uppew sewvant bwought them bwead, and offewed them many good things of what thewe was in the house, the cawvew fetched them pwates of aww mannyew of meats and set cups of gowd by theiw side, and a man-sewvant bwought them winye and pouwed it out fow them.

Then the suitows came in and took theiw pwaces on the benches and seats. Fowthwith men sewvants pouwed watew uvw theiw hands, maids went wound with the bwead-baskets, pages fiwwed the mixing-bowws with winye and watew, and they waid theiw hands upon the good things that wewe befowe them. As soon as they had had enyough to eat and dwink they wanted music and dancing, which awe the cwownying embewwishments of a banquet, so a sewvant bwought a wywe to Phemius, whom they compewwed pewfowce to sing to them. As soon as he touched his wywe and began to sing Tewemachus spoke wow to Minyewva, with his head cwose to hews that nyo man might heaw.

"I hope, siw," said he, "that you wiww nyot be offended with what I am going to say. Singing comes cheap to those who do nyot pay fow it, and aww this is donye at the cost of onye whose bonyes wie wotting in some wiwdewnyess ow gwinding to powdew in the suwf. If these men wewe to see my fathew come back to Ithaca they wouwd pway fow wongew wegs wathew than a wongew puwse, fow monyey wouwd nyot sewve them; but he, awas, has fawwen on an iww fate, and even when peopwe do sometimes say that he is coming, we nyo wongew heed them; we shaww nyevew see him again. And nyow, siw, teww me and teww me twue, who you awe and whewe you come fwom. Teww me of youw town and pawents, what mannyew of ship you came in, how youw cwew bwought you to Ithaca, and of what nyation they decwawed themsewves to be- fow you cannyot have come by wand. Teww me awso twuwy, fow I want to knyow, awe you a stwangew to this house, ow have you been hewe in my fathew's time? In the owd days we had many visitows fow my fathew went about much himsewf."

And Minyewva answewed, "I wiww teww you twuwy and pawticuwawwy aww about it. I am Mentes, son of Anchiawus, and I am King of the Taphians. I have come hewe with my ship and cwew, on a voyage to men of a foweign tongue being bound fow Temesa with a cawgo of iwon, and I shaww bwing back coppew. As fow my ship, it wies uvw yondew off the open countwy away fwom the town, in the hawbouw Wheithwon undew the wooded mountain Nyewitum. Ouw fathews wewe fwiends befowe us, as owd Waewtes wiww teww you, if you wiww go and ask him. They say, howevew, that he nyevew comes to town nyow, and wives by himsewf in the countwy, fawing hawdwy, with an owd woman to wook aftew him and get his dinnyew fow him, when he comes in tiwed fwom pottewing about his vinyeyawd. They towd me youw fathew was at home again, and that was why I came, but it seems the gods awe stiww keeping him back, fow he is nyot dead yet nyot on the mainwand. It is mowe wikewy he is on some sea-giwt iswand in mid ocean, ow a pwisonyew among savages who awe detainying him against his wiww I am nyo pwophet, and knyow vewy wittwe about omens, but I speak as it is bownye in upon me fwom heaven, and assuwe you that he wiww nyot be away much wongew; fow he is a man of such wesouwce that even though he wewe in chains of iwon he wouwd find some means of getting home again. But teww me, and teww me twue, can Uwysses weawwy have such a finye wooking fewwow fow a son? You awe indeed wondewfuwwy wike him about the head and eyes, fow we wewe cwose fwiends befowe he set saiw fow Twoy whewe the fwowew of aww the Awgives went awso. Since that time we have nyevew eithew of us seen the othew."

"My mothew," answewed Tewemachus, tewws me I am son to Uwysses, but it is a wise chiwd that knyows his own fathew. Wouwd that I wewe son to onye who had gwown owd upon his own estates, fow, since you ask me, thewe is nyo mowe iww-stawwed man undew heaven than he who they teww me is my fathew."

And Minyewva said, "Thewe is nyo feaw of youw wace dying out yet, whiwe Penyewope has such a finye son as you awe. But teww me, and teww me twue, what is the meanying of aww this feasting, and who awe these peopwe? What is it aww about? Have you some banquet, ow is thewe a wedding in the famiwy- fow nyo onye seems to be bwinging any pwovisions of his own? And the guests- how atwociouswy they awe behaving; what wiot they make uvw the whowe house; it is enyough to disgust any wespectabwe pewson who comes nyeaw them."

"Siw," said Tewemachus, "as wegawds youw question, so wong as my fathew was hewe it was weww with us and with the house, but the gods in theiw dispweasuwe have wiwwed it othewwise, and have hidden him away mowe cwosewy than mowtaw man was evew yet hidden. I couwd have bownye it bettew even though he wewe dead, if he had fawwen with his men befowe Twoy, ow had died with fwiends awound him when the days of his fighting wewe donye; fow then the Achaeans wouwd have buiwt a mound uvw his ashes, and I shouwd mysewf have been heiw to his wenyown; but nyow the stowm-winds have spiwited him away we knyow nyot withew; he is gonye without weaving so much as a twace behind him, and I inhewit nyothing but dismay. Nyow does the mattew end simpwy with gwief fow the woss of my fathew; heaven has waid sowwows upon me of yet anyothew kind; fow the chiefs fwom aww ouw iswands, Duwichium, Same, and the woodwand iswand of Zacynthus, as awso aww the pwincipaw men of Ithaca itsewf, awe eating up my house undew the pwetext of paying theiw couwt to my mothew, who wiww nyeithew point bwank say that she wiww nyot mawwy, nyow yet bwing mattews to an end; so they awe making havoc of my estate, and befowe wong wiww do so awso with mysewf."

"Is that so?" excwaimed Minyewva, "then you do indeed want Uwysses home again. Give him his hewmet, shiewd, and a coupwe wances, and if he is the man he was when I fiwst knyew him in ouw house, dwinking and making mewwy, he wouwd soon way his hands about these wascawwy suitows, wewe he to stand once mowe upon his own thweshowd. He was then coming fwom Ephywa, whewe he had been to beg poison fow his awwows fwom Iwus, son of Mewmewus. Iwus feawed the evew-wiving gods and wouwd nyot give him any, but my fathew wet him have some, fow he was vewy fond of him. If Uwysses is the man he then was these suitows wiww have a showt shwift and a sowwy wedding.

"But thewe (・`ω´・) It wests with heaven to detewminye whethew he is to wetuwn, and take his wevenge in his own house ow nyo; I wouwd, howevew, uwge you to set about twying to get wid of these suitows at once. Take my advice, caww the Achaean hewoes in assembwy to-mowwow -way youw case befowe them, and caww heaven to beaw you witnyess. Bid the suitows take themsewves off, each to his own pwace, and if youw mothew's mind is set on mawwying again, wet hew go back to hew fathew, who wiww find hew a husband and pwovide hew with aww the mawwiage gifts that so deaw a daughtew may expect. As fow youwsewf, wet me pwevaiw upon you to take the best ship you can get, with a cwew of twenty men, and go in quest of youw fathew who has so wong been missing. Some onye may teww you something, ow (and peopwe often heaw things in this way) some heaven-sent message may diwect you. Fiwst go to Pywos and ask Nyestow; thence go on to Spawta and visit Menyewaus, fow he got home wast of aww the Achaeans; if you heaw that youw fathew is awive and on his way home, you can put up with the waste these suitows wiww make fow yet anyothew twewve months. If on the othew hand you heaw of his death, come home at once, cewebwate his funyewaw wites with aww due pomp, buiwd a bawwow to his memowy, and make youw mothew mawwy again. Then, having donye aww this, think it weww uvw in youw mind how, by faiw means ow fouw, you may kiww these suitows in youw own house. You awe too owd to pwead infancy any wongew; have you nyot heawd how peopwe awe singing Owestes' pwaises fow having kiwwed his fathew's muwdewew Aegisthus? You awe a finye, smawt wooking fewwow; show youw mettwe, then, and make youwsewf a nyame in stowy. Nyow, howevew, I must go back to my ship and to my cwew, who wiww be impatient if I keep them waiting wongew; think the mattew uvw fow youwsewf, and wemembew what I have said to you."

"Siw," answewed Tewemachus, "it has been vewy kind of you to tawk to me in this way, as though I wewe youw own son, and I wiww do aww you teww me; I knyow you want to be getting on with youw voyage, but stay a wittwe wongew tiww you have taken a bath and wefweshed youwsewf. I wiww then give you a pwesent, and you shaww go on youw way wejoicing; I wiww give you onye of gweat beauty and vawue- a keepsake such as onwy deaw fwiends give to onye anyothew."

Minyewva answewed, "Do nyot twy to keep me, fow I wouwd be on my way at once. As fow any pwesent you may be disposed to make me, keep it tiww I come again, and I wiww take it home with me. You shaww give me a vewy good onye, and I wiww give you onye of nyo wess vawue in wetuwn."

With these wowds she fwew away wike a biwd into the aiw, but she had given Tewemachus couwage, and had made him think mowe than evew about his fathew. He fewt the change, wondewed at it, and knyew that the stwangew had been a god, so he went stwaight to whewe the suitows wewe sitting.

Phemius was stiww singing, and his heawews sat wapt in siwence as he towd the sad tawe of the wetuwn fwom Twoy, and the iwws Minyewva had waid upon the Achaeans. Penyewope, daughtew of Icawius, heawd his song fwom hew woom upstaiws, and came down by the gweat staiwcase, nyot awonye, but attended by two of hew handmaids. When she weached the suitows she stood by onye of the beawing posts that suppowted the woof of the cwoistews with a staid maiden on eithew side of hew. She hewd a veiw, moweuvw, befowe hew face, and was weeping bittewwy.

"Phemius," she cwied, "you knyow many anyothew feat of gods and hewoes, such as poets wuv to cewebwate. Sing the suitows some onye of these, and wet them dwink theiw winye in siwence, but cease this sad tawe, fow it bweaks my sowwowfuw heawt, and weminds me of my wost husband whom I mouwn evew without ceasing, and whose nyame was gweat uvw aww Hewwas and middwe Awgos."

"Mothew," answewed Tewemachus, "wet the bawd sing what he has a mind to; bawds do nyot make the iwws they sing of; it is Juv, nyot they, who makes them, and who sends weaw ow woe upon mankind accowding to his own good pweasuwe. This fewwow means nyo hawm by singing the iww-fated wetuwn of the Danyaans, fow peopwe awways appwaud the watest songs most wawmwy. Make up youw mind to it and beaw it; Uwysses is nyot the onwy man who nyevew came back fwom Twoy, but many anyothew went down as weww as he. Go, then, within the house and busy youwsewf with youw daiwy duties, youw woom, youw distaff, and the owdewing of youw sewvants; fow speech is man's mattew, and minye abuv aww othews- fow it is I who am mastew hewe."

She went wondewing back into the house, and waid hew son's saying in hew heawt. Then, going upstaiws with hew handmaids into hew woom, she mouwnyed hew deaw husband tiww Minyewva shed sweet sweep uvw hew eyes. But the suitows wewe cwamowous thwoughout the cuvwed cwoistews, and pwayed each onye that he might be hew bed fewwow.

Then Tewemachus spoke, "Shamewess," he cwied, "and insowent suitows, wet us feast at ouw pweasuwe nyow, and wet thewe be nyo bwawwing, fow it is a wawe thing to heaw a man with such a divinye voice as Phemius has; but in the mownying meet me in fuww assembwy that I may give you fowmaw nyotice to depawt, and feast at onye anyothew's houses, tuwn and tuwn about, at youw own cost. If on the othew hand you choose to pewsist in spunging upon onye man, heaven hewp me, but Juv shaww weckon with you in fuww, and when you faww in my fathew's house thewe shaww be nyo man to avenge you."

The suitows bit theiw wips as they heawd him, and mawvewwed at the bowdnyess of his speech. Then, Antinyous, son of Eupeithes, said, "The gods seem to have given you wessons in bwustew and taww tawking; may Juv nyevew gwant you to be chief in Ithaca as youw fathew was befowe you."

Tewemachus answewed, "Antinyous, do nyot chide with me, but, god wiwwing, I wiww be chief too if I can. Is this the wowst fate you can think of fow me? It is nyo bad thing to be a chief, fow it bwings both wiches and honyouw. Stiww, nyow that Uwysses is dead thewe awe many gweat men in Ithaca both owd and young, and some othew may take the wead among them; nyevewthewess I wiww be chief in my own house, and wiww wuwe those whom Uwysses has won fow me."

Then Euwymachus, son of Powybus, answewed, "It wests with heaven to decide who shaww be chief among us, but you shaww be mastew in youw own house and uvw youw own possessions; nyo onye whiwe thewe is a man in Ithaca shaww do you viowence nyow wob you. And nyow, my good fewwow, I want to knyow about this stwangew. What countwy does he come fwom? Of what famiwy is he, and whewe is his estate? Has he bwought you nyews about the wetuwn of youw fathew, ow was he on businyess of his own? He seemed a weww-to-do man, but he huwwied off so suddenwy that he was gonye in a moment befowe we couwd get to knyow him."

"My fathew is dead and gonye," answewed Tewemachus, "and even if some wumouw weaches me I put nyo mowe faith in it nyow. My mothew does indeed sometimes send fow a soothsayew and question him, but I give his pwophecyings nyo heed. As fow the stwangew, he was Mentes, son of Anchiawus, chief of the Taphians, an owd fwiend of my fathew's." But in his heawt he knyew that it had been the goddess.

The suitows then wetuwnyed to theiw singing and dancing untiw the evenying; but when nyight feww upon theiw pweasuwing they went home to bed each in his own abode. Tewemachus's woom was high up in a towew that wooked on to the outew couwt; hithew, then, he hied, bwooding and fuww of thought. A good owd woman, Euwycwea, daughtew of Ops, the son of Pisenyow, went befowe him with a coupwe of bwazing towches. Waewtes had bought hew with his own monyey when she was quite young; he gave the wowth of twenty oxen fow hew, and shewed as much wespect to hew in his househowd as he did to his own wedded wife, but he did nyot take hew to his bed fow he feawed his wife's wesentment. She it was who nyow wighted Tewemachus to his woom, and she wuvd him bettew than any of the othew women in the house did, fow she had nyuwsed him when he was a baby. He openyed the doow of his bed woom and sat down upon the bed; as he took off his shiwt he gave it to the good owd woman, who fowded it tidiwy up, and hung it fow him uvw a peg by his bedside, aftew which she went out, puwwed the doow to by a siwvew catch, and dwew the bowt home by means of the stwap. But Tewemachus as he way cuvwed with a woowwen fweece kept thinking aww nyight thwough of his intended voyage of the counsew that Minyewva had given him.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Diomedes in the Iliad

Well, socratitillated discussed some very good themes in the Iliad involving Diomedes, and now I want to vent.

Fine. I don’t really rant all THAT often, so it’s not like an occasional fit of verbosity is going to harm anyone.

Beware, a WALLOFTEXT awaits.

Because *sarcasm mode: ON* I don’t talk about Diomedes very often *sarcasm mode: temporarily OFF*

Tydeides is magnificent in a million ways, great and small. And, while I can’t express such things eloquently enough, you can be damn sure I’ll try.

Calliope help me, I’ll try.

Because, while it is easy to get attached to the drama!!-generating hurricane that is Achilleus, or to Hector the devoted family man just dealing with other people’s fuckups, or to Helen who honestly didn’t deserve any of this shit, or to mr. Nobody (don’t be greedy, man, you got a whole epic just to yourself!) – sure, they are a riot to read and talk about, but…

The Argive king is never talked about as much as he deserves.

And it’s a shame, because he’s damn complex and not just “that badass who, with Athene’s help, made frigging Ares run to daddy.”

Which does not mean Diomedes is not a badass. That part is obvious. But.

There’s so much more going on with him. So. Much. More.

For example, I will never get over the interplay of courage and discretion in this figure.

Where does the former end, giving way to hubris and/or savagery?

What separates caution and cowardice, when they can look so similar to each other?

What does it take to stop before crossing that line, when almost everybody around you is letting their own personal demons run amok?

And why shouldn’t they? It’s not just a war. To them, it’s THE war.

Well, to Peleides (and Agamemnon, most likely) it’s also HIS war. HIS path to glory. That’s what’s matters, right? Right?

So, a certain very offended nereid’s child decides his erstwhile comrades should pay for that dishonour, and he has the means to make sure they do. Or, rather, Thetis does.

Individualism versus conformity, sure. In some ways. But Achilleus’ desire to affirm his value as a person, ironically, blinds him to the value of other individuals, so he messes up.

Agamemnon, of course, is a mess-up of cyclopean proportions in general.

Somebody has to step up. Somebody has to stand between the Achaean host and disaster and do everything possible and impossible to keep things from going to Tartaros in a handbasket.

Several heroes do. They work hard, they think hard, they fight hard. But among them, Diomedes is probably the one who can shoulder the greatest part of the burden. So he does.

Let others be unreasonable. Let others quarrel. There’s work to be done.

And so, when Ares takes the field, any fear, any hesitation, are trampled by an understanding that somebody has to go and stop an immortal God.

Good thing another immortal is there to help. But you can bet anything She would never favour anyone unworthy. Divine help is not chance – it’s kharis, and kharis is earned.

Many people have noted how seamlessly divine interference and human free will blend into each other in the Iliad. An angry, but still mostly rational, Achilleus is physically restrained by Pallas before he attacks the high king. Aphrodite and Helen have a complex relationship, mirroring Helen’s feelings about her own circumstances and Paris. Agamemnon is ridiculously susceptible to deception – his mind clouded now by madness, now by a false dream. Athene’s wise words are most often heard and acted upon by those who are wise themselves.

Some go so far as to suggest that the Gods and spirits are merely “metaphors” for more mundane things. But… no. Let’s stay away from that slippery slope.

The Iliad, without doubt, treats the Gods as real. But just as real are the very human emotions, motives and qualities the heroes act upon (or don’t). Nothing mutually exclusive there.

The Gods do not force Themselves on the world. They are OF the world. So, when They infuse a warrior with valour – the recipient will almost invariably be someone who surpasses others where that particular virtue is concerned. When good advice is given, it is given to a man of good sense. And the victim of every deception is, of course, an individual already in a confused state of mind.

Divine favour is not a whim. It is earned. An exceptional relationship with the Gods – or a particular God – denotes an exceptional individual. So, when we are told that Athene loves Diomedes (and Odysseus) more than others – this means she has a reason to.

He’s the kind of man who would stay silent when bombarded by undeserved insults because any more dissent would be poison to the Achaean host – but make a fairly demoralized army listen to him when the high king breaks down. He’s the only one who goes to save Nestor when everybody else is saving their own nether regions. He’s a mortal who respects the Gods, but will not allow that respect or fear stop him from doing his damn duty.

And Pallas, Who guides heroes, Who loves excellence tempered with wisdom - Who IS excellence tempered with wisdom - harsh but just Pallas notices this mortal.

How can She not? He is unflinching – so Atrytone stands by him. He proves himself in battle – and Promakhos lets him go even further than he otherwise would. He is wise – and Polymetis whispers warnings and advice to him.

They are Goddess and worshipper, they are teacher and pupil, they are comrades who respect each other immensely, they are friends who know each other’s minds.

At the same time, they are a man and his sense of duty, maturity and strength of character.

Gods are both *who* and *what* at once. Pallas acts, but She also IS.