#a little monastery in tuscany

Text

Did you know there's a copy of the Shroud of Turin in New Jersey?

…and it's been there for 100 years!

The Shroud of Turin, the most fascinating relic preserved by the Church, was widely venerated by the start of the 17th century. It has a mysterious history, one that has been studied intensely for many, many years.

Holy_Face_of_Jesus_from_Shroud_of_Turin-300x382

Sketch of the Shroud by St. Thérèse's sister, Sr. Geneviève of the Holy Face

Little-known fact: the Shroud has been copied for devotional purposes, and in miraculous circumstances.

Here are the facts.

Maria Maddelena, the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, commissioned a copy of the Holy Shroud in 1624.

After the copy was made, it was laid right on top of the actual Shroud, so that it could be venerated as a third class relic.

What happened next astonished everyone.

The copy was lifted off the original, and a damp mark—like blood—was found on the Shroud's side wound.

The dark fluid had seeped into the copy lying on top.

300 years later, the scientists who examined the Holy Shroud analyzed its copy. The test results awed them: the dark patch was blood. The same blood as that on the original Shroud.

The rest, as they say, is history.

The Dominicans of St. Clare's Monastery in Rome received the shroud copy as a gift from Maddelena. Keeping it in their care for 300 years, they gave it to the Dominican monastery in Summit, New Jersey after World War I.

Source: http://24101925.hs-sites.com/gf_022024_bb_sunday_feb_18?ecid=ACsprvs0G_907kkVq2koE_Nf7JuN-s-evIIbNPXj2NaddIbssAHcvGp1su9E64ORmXbeh_EMGtVv&utm_campaign=GF_022024_BB_Sunday_Feb_18&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=294303544&_hsenc=p2ANqtz--94KowVyVNETmHUTyy4AC97IwZ3i6Y8oTuq3BUxdtCPxiwbTV4UYIaxdrwfIpaxvvYj7QhWZMOPjPO9EH22oRH4Su7Dw&utm_content=294303544&utm_source=hs_email

0 notes

Text

{From Townsend}

Last time I wrote we were in Spain and since then we’ve traveled through France and now are in our last 2 days in Italy. France overall was a really fun experience. I enjoyed it the most so far. I enjoyed staying in our house in Avignon and the town in general. I liked all the back streets as well as how it wasn’t a huge city with a lot of tourists. During our time there we saw some cool structures that left me extremely impressed and interested on the people of that time period. We also had a lot of good French food.

On Friday we took a flight from France to Italy. The flight was short so we still had plenty of time to experience Florence on our first day there. When we arrived we got sandwiches from s very popular spot and the sandwiches did not disappoint. We then walked around the city for a little bit as well saw the David statue. The statue was pretty cool and was fun to see such a popular and praised spot in Florence. We ate dinner that night at a pasta restaurant and I got Gnocchi. It surprised me and I ended up enjoying it a lot. After dinner we then of course got gelato and that wrapped up our day in Friday.

Yesterday was the most eventful day throughout the entirety of the trip. We first woke up early and climbed to the top of the Duomo which was a little tiring but also was worth it to see the whole city and take some cool photos. We then came back to the hotel and me and my mom went and walked around to a market then came back. We took a little brake and then went to some towns outside of Florence for the rest of the afternoon until after dinner. We first went to San Gimignano which was a little medieval village in the hills of Tuscany. I thought it was pretty cool walking around it. I ended up getting three photo prints as a souvenir. During our time there we ended up seeing a parade/celebration. We then went to Siena and walked around and ate out dinner there. We all got pizzas which were very delicious and ended up being just perfect. As of writing this me and my dad had just came back from walking up to a monastery nearby and exploring and my mom and sisters are currently in a cooking class. That’s all from me, Thanks for reading.

0 notes

Text

Sept 5, 2022: Gambassi Terme to San Gimignano - 15 km CUS 1500 feet

Simple is Sometimes Best

Stayed the night at a charming little B&B Villa Della Certossa in Gambassi Terme. It even came complete with a hot tub that wasn’t actually hot (not a problem in 30+ heat). The owner is a lovely older woman and is the first person to support our mask wearing as she has a pacemaker.

She sent us to the main square to eat at Il Gato e La Volpe (The Cat and the Fox from Pinocchio) where they played no fairy tale tricks upon us. Instead it was a simple but delicious meal of the house specialty penne (tomato sauce, cippolini, pancetta, basil, oregano, bay leaf?) followed by a plump lemon chicken breast that must have been tenderized and moisturized by some magical Italian process before being sautéed. It was accompanied by grilled vegetables and 1/2 litre of the house white while enjoying all the families out in the square (infants to ancients) on their late evening passeggiata. Also had a nice chat with a fellow walker, Xavier from Brisbane. This is his first long walk at age 75 and he is disdainful of using apps and gps to wayfind. I suspect this purism will only last until the first time he makes a wrong turn and walks a couple of extra kilometres.

A short day, but it seemed to be in the 30s by about 10:30. Lots of up and down in a short distance. There were a couple of handy roadside fountains from which I repeated filled my water bottle and poured it over my head. This worked well until one of them had a high sulphur content,which left a lasting impression. Walking the hills in Tuscany is deceiving. You can see a hill crest ahead of you and you think “if I can just make it the next Kilometre and 100 m of climb it’s all down hill from there”. You reach that crest, only to discover that it is a small ledge/plateau hiding another brutal 100m climb (think MacDougall Hill stairs) to the next ledge, and so on. It is almost like they are teasing you. It took us a total of 5 hours to go only 15 km. We were quicker at end because we could see the San Gimignano skyline in the distance and we eschewed a detour to the top of one hill to visit a monastery.

I have been to San Gimignano three times and it holds a lot of very special memories for me. Nearby farm houses and converted barns can be rented by the week as a base of operations for touring Tuscan hill towns by car (hill country means no trains). However, San Gimignano itself is Banff with towers. Packed with tourists shoulder to shoulder at midday (40-50 lined up for one gelato shop) and completely buried in cheap souvenir stores, Kim described it as Medieval Disneyland without the rides or Mickey Mouse. What else can you say about a town that support two torture museums.

San Gimignano is most famous for its medieval towers with 14 of the original 72 towers still surviving. They were built for inter- and intra-city defence when the town was a trading crossroads and very wealthy. The tower entrances are 1-2 stories up so that the outdoor wooden stairways could simply be burned off when under attack. The towns affluence collapsed in the mid-14th century when plague killed off 2/3 of its population and like other sudden backwaters, this decline preserved its medieval character. For my money, the towers’ primary purpose was not defence, but as a symbol of male ego and power (appropriate given their size and shape).

The Cathedral is worth a visit, if only because it is completely lined with beautiful frescos (paint infused plaster) including several by major artists. My favourites are The Annunciation of the Death of Santa Fina and the Funeral of Santa Fina by Dominico Ghirlandaio. This may make me sound a little sophisticated until you learn that my first encounter with them was the movie “Tea with Mussolini” where Judy Dench, Maggie Smith and Cher tried to save them from Allied bombing in WWII bombing. On a more contemporary note, Kim and I revisited a commercial gallery that was among my favourites in the world the last time I was here. I still have the business card at home after 13 years. Previously, the art was full of emotion, passion, angst and often a great deal talent. Today, sadly, there were a few pieces that were interesting and well done, but most were merely pretty (done skillfully) and, in my opinion, soulless. On display across the street, however, (“by appointment only”) was a sculpture that appeared to be a genuine Giacometti. If so, a wee bit out of my price range😂.

Tomorrow, another short day to Colle de Val d’Elsa, another hill town that I have visited in the past. If I remember clearly (highly unlikely).it is a centre for crystal glass production and carved alabaster. I think it unlikely that either will end up in my day pack.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Un petit monastère en Toscane / A Little Monastery in Tuscany

Otar Iosseliani. 1988

Monastery

Localita' S. Antimo, 222, 53024 Castelnuovo dell'Abate SI, Italy

See in map

See in imdb

#otar iosseliani#un petit monastère en toscane#a little monastery in tuscany#italy#monastery#montalcino#castelnuovo dell abate#siena#tuscany#movie#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#1988

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

Haikyuu!! and its Saints

Fly to victory. In celebration of my birthday today, here's our black and orange boys of Karasuno and their corresponding saints!

December 31 - Daichi Sawamura

Pope St. Sylvester I: 33rd bishop of Rome who reigned from 314 to 335 A.D. He filled the see of Rome at an important era in the history of the Western Church, yet very little is known of him. The accounts of his pontificate preserved in the seventh or eighth-century Liber Pontificalis contain little more than a record of the gifts said to have been conferred on the church by Constantine the Great, although it does say that he was the son of a Roman named Rufinus. Large churches were founded and built during Sylvester I's pontificate, including Basilica of St. John Lateran, Basilica of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem, Old St. Peter's Basilica and several churches built over the graves of martyrs. Legend has it that Sylvester is slaying a dragon, hence he is often depicted with the dying beast.

June 13 - Koshi Sugawara

St. Anthony of Padua: Franciscan Portuguese friar and priest who is noted by his contemporaries for his powerful preaching, expert knowledge of scripture, and undying love and devotion to the poor and the sick, he was one of the most quickly canonized saints in church history. Although he is known as the patron of lost items, his major shrine can be found in Padua, Italy. In January 1946, he is proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XII, and is given the title of Doctor Evangelicus (Evangelical Doctor).

January 1 - Asahi Azumane

Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God: One of the most important Marian feasts days to start the New Year. It is to honor the Blessed Virgin Mary under the aspect of her motherhood of Jesus Christ, whom Christians see as the Lord, Son of God, and it is celebrated by the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church on 1 January, the Octave (8th) day of Christmastide.

October 10 - Yu Nishinoya

St. Cerbonius: Populonian bishop who lived in the time of the Barbarian invasion. Gregory the Great praises him in Book XI of his Dialogues. Another tradition states that Cerbonius was a native of North Africa who was the son of Christian parents. Ordained a priest by Regulus, though not the same one as in the Scottish Legend. One of the saint’s attributes was a bear licking his feet, because during Totila’s invasion of Tuscany, he was ordered to be killed by a wild bear, the bear remained petrified before him. It stood on two legs and opened its jaws wide. Then, it fell back on its paws and licked the feet of the saint.

March 3 - Ryunosuke Tanaka

St. Katharine Drexel: American philanthropist, religious sister, educator, heiress, and foundress of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament, as well as Xavier University of Louisiana, the only historically black Catholic college in the country. She might be the second canonized saint to have been born in the United States and the first to have been born a U.S. citizen, she is the patron of philanthropists and racial justice.

December 26 - Chikara Ennoshita

St. Stephen: Dubbed as the first Christian martyr, and his appearance can be found in the Acts of the Apostles. He is a deacon in the early church at Jerusalem who aroused the enmity of members of various synagogues by his teachings. Accused of blasphemy at his trial, he made a long speech denouncing the Jewish authorities who were sitting in judgment on him and was then stoned to death, in which Saul of Tarsus was a witness to see him died before his conversion in Damascus.

February 15 - Hisashi Kinoshita

St. Claude de La Colombière: 17th century French Jesuit priest who assisted St. Margaret Mary Alacoque in establishing the devotion to the Sacred Heart. He was her confessor, and his writings and testimony helped to validate her mystical visions and elevated the Sacred Heart as an important feature of Roman Catholic devotion. He was appointed court preacher to Mary of Modena, who had become duchess of York by marriage with the future King James II of England, and he took up his residence in St. James's Palace in London. Falsely accused by a former protégé of complicity in Titus Oates's 'popish plot,' he was imprisoned for five weeks and, when released, was obliged to return to France, where he died an invalid under the care of Margaret Mary. Canonized by Pope St. John Paul II on the Feast of the Visitation in 1992, his major shrine can be found in Paray-le-Monial.

August 17 - Kazuhito Narita

St. Hyacinth of Poland: 13th century Polish Dominican priest and missionary who worked to reform women's monasteries in his native Poland, and was a Doctor of Sacred Studies, educated in Paris and Bologna, and is known for the monicker, 'Apostle of the North.' One of the major miracles attributed to Hyacinth came about during a Mongol attack on Kiev. As the friars prepared to flee the invading forces, Hyacinth went to save the ciborium containing the Blessed Sacrament from the tabernacle in the monastery chapel, when he heard the voice of Mary, the mother of Jesus, asking him to take her, too. He lifted the large, stone statue of Mary, as well as the ciborium. He was easily able to carry both, despite the fact that the statue weighed far more than he could normally lift. Thus he saved them both. His tomb is in the Basilica of Holy Trinity in Krakow, Poland, in a chapel that bears his name. Hyacinth is the patron saint of those in danger of drowning.

December 22 - Tobio Kageyama

St. Ernan, Son of Eogan: He was a nephew of St. Columba. His monastery in Ireland was at Druim-Tomma in the district of Drumhome, County Donegal. He is venerated as the patron saint of Killernan, though he may not have visited Scotland and also as patron of the parish of Drumhome, where a school has been dedicated to him. His commemoration is assigned to the 21st and 22nd of December according to the Scottish Kalendars.

June 21 - Shoyo Hinata

St. Aloysius Gonzaga: Italian confessor from the Jesuit order. Born into the noble Gonzaga clan in 1568, and in order to satisfy his father's ambitions, he was trained in the art of war and was obliged to attend royal banquets and military parades. Not with standing his father's furious opposition, Aloysius renounced his inheritance and join the Jesuits in Rome. While still a student at the Roman College, he died as a result of caring for the victims of a serious epidemic. Canonized on New Year’s Eve in 1726 by Pope Benedict XIII, he is the patron saint of the Christian youth, Jesuit scholastics, the blind, AIDS patients, AIDS care-givers.

September 27 - Kei Tsukishima

St. Vincent de Paul: 17th century French priest who is the founder of the Congregation of the Mission (the Vincentians) for preaching missions to the peasantry and for educating and training a pastoral clergy. The patron saint of charitable societies, he is primarily recognized for his charity and compassion for the poor, though he is also known for his reform of the clergy and for his early role in opposing Jansenism. With St. Louise de Marillac, he co-founded the Daughters of Charity (Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul) in 1633. The association was patterned after the Confraternities of Charity and was the first noncloistered religious institute of women devoted to active charitable works. Canonized as a saint by Pope Clement XII in 1737, his major shrine can be found in Rue de Sèvres in Paris.

November 10 - Tadashi Yamaguchi

St. Leo the Great (Pope St. Leo I): 45th bishop of Rome who reigned from 440 to 461 A.D. His pontificate - which saw the disintegration of the Roman Empire in the West and the formation in the East of theological differences that were to split Christendom—was devoted to safeguarding orthodoxy and to securing the unity of the Western church under papal supremacy. He is perhaps best known for having met Attila the Hun in 452 and allegedly persuaded him to turn back from his invasion of Italy. Leo is mostly remembered theologically for issuing the Tome of Leo, a document which was a major foundation to the debates of the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon. Pope Benedict XIV proclaimed Leo I a Doctor of the Church in 1754, next to one other pope, St. Gregory the Great.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#haikyuu!!#karasuno high school#daichi sawamura#koshi sugawara#asahi azumane#yu nishinoya#ryunosuke tanaka#chikara ennoshita#hisashi kinoshita#kazuhito narita#tobio kageyama#shoyo hinata#kei tsukishima#tadashi yamaguchi

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Padre Pio Inspirational Story

Padre Pio and his Friend from Donegal, Ireland — John McCaffery — Part - II

On John McCaffery’s many visits to San Giovanni Rotondo, he met a number of people who were very close friends of Padre Pio. One was Dr. Guglielmo Sanguinetti. Dr. Sanguinetti was one of the major collaborators in the building of Padre Pio’s hospital, the Home for the Relief of Suffering.

One day when John was at the monastery, he was happy to run into Dr. Sanguinetti as well as one other acquaintance. Dr. Sanguinetti suggested that the three of them go to the small room adjoining the choir loft and discuss some of the upcoming plans for the Home for the Relief of Suffering. At the time, Dr. Sanguinetti was heavily burdened with many difficult decisions that he had to make regarding the hospital. He was trying to raise funds, publish an informational newspaper regarding the hospital, and oversee the construction plans.

The informal business meeting that Dr. Sanguinetti suggested would cause the men to miss the sermon that was about to begin in the church. However, they would be finished with their discussion by the time Padre Pio was ready to preside at Benediction. “You know, the sermons of the visiting Capuchin are boring,” Dr. Sanguinetti said. “I am not able to stay awake when he is preaching. We will just talk together quietly while the sermon is going on. When we hear Mary Pyle and her choir start to sing, it will be our cue to go in the church for Benediction.”

The plan sounded like a good one, but the men would soon regret it. When Padre Pio rounded the corner and saw the three men discussing business together, he became angry. John and his two companions instantly regretted their decision, but it was too late. “How could you do it?” Padre Pio said. “How could you have a discussion while the Capuchin is preaching a sermon? You must go downstairs at once to the church!” The tension in the air was mounting by the minute. To the men, it seemed like Padre Pio had overreacted. Nevertheless, they followed his advice and went into the church. Later, John and Dr. Sanguinetti would recall the incident and see the humor in it, but at the time it happened, it was no laughing matter.

Through the years, John observed that Dr. Sanguinetti always seemed to feel totally at ease whenever he was with Padre Pio. That was rare. Because almost everyone had a certain awe of Padre Pio, it was very difficult for most people to feel completely comfortable in his presence. Not Dr. Sanguinetti. He was able to be truly natural, truly “himself.” Knowing that, Padre Pio could let his guard down and could relax in his company. It was something that he was not able to do with many people.

Once, John and Dr. Sanguinetti were saying goodbye to Padre Pio after visiting him. Padre Pio suddenly became serious. For some time, he stared intently at John and at Dr. Sanguinetti and finally said to them, “Who knows when and where we will meet again.” John wondered what Padre Pio meant by the mysterious comment. Shortly after that and quite unexpectedly, Dr. Sanguinetti died of a heart attack. His death came as a terrible blow to Padre Pio and it left a great void in his heart. It seemed that no one was able to console Padre Pio over the loss of his dear friend.

Several months later, John returned to San Giovanni Rotondo for a visit. When Padre Pio saw John, he began to cry. They went into a private room in the monastery so that they could talk together. “You probably did not think that you would ever see me in a state such as this,” Padre Pio said to John. The tears flowed freely from his eyes. “We lost our good friend,” Padre Pio added. “Unlike you or me, God saw that Dr. Sanguinetti was ready to be with Him in eternal life.” John tried to comfort Padre Pio in his sorrow but no words could

console him.

In addition to Dr. Sanguinetti, another one of Padre Pio’s spiritual children that John felt fortunate to meet was a woman named Elena Bandini. Elena, a Third Order Franciscan, had dedicated herself totally to her faith and to many charitable and apostolic works. She began writing to Padre Pio and seeking his spiritual direction in 1921. In 1937, she moved from her home in Mugello to live permanently in San Giovanni Rotondo. She served Padre Pio’s apostolate in innumerable ways.

When Elena was diagnosed with stomach cancer, her strength of character and her heroic spirit became apparent to all. The suffering that Elena endured was almost unbearable. However, she did not pray for a healing. She offered all of her sufferings to God and united them to Padre Pio’s sufferings, for his intentions. John visited Elena right before she died. His heart was moved with pity to see her in so much pain. Her resignation to her illness was beautiful and her profound spirituality was evident, even on her death bed. Finally, her sufferings became so intense that she prayed to Padre Pio that her end would come. “It will just be a little longer. Just a little more straw to burn,” Padre Pio said. Elena finally passed away on October 5, 1955. John spoke to Padre Pio about her death. “Elena was such a saintly person,” John said. “She lived a holy life and she died a holy death. I believe that she went straight to heaven.” Two large tears rolled down Padre Pio’s cheeks. “Oh yes, that is true,” Padre Pio replied. “Elena went to heaven with no stop at all!”

During one of his visits to the monastery of Our Lady of Grace, John met a man named Giovanni and soon they became fast friends. Giovanni was known simply as Giovanni da Prato, since he was originally from Prato, Italy. He had a deep conversion experience through his contact with Padre Pio and was able to completely reform his life.

Giovanni da Prato drove a taxi for a living and in times past, he had a serious drinking problem. When he drank too much, he would often become violent. Once, after an evening of excessive drinking, he struck his wife and then collapsed in a drunken stupor across the bed. Suddenly, he felt the bed moving. He looked up to see a Capuchin, holding onto the bed rail and shaking the bed. The Capuchin, who had a very angry look on his face, was staring directly at Giovanni. “You have gone too far this time!” the dark-robed figure said to Giovanni. With that, the Capuchin disappeared.

Giovanni told his wife about the mysterious Capuchin who had stood beside his bed. “I have been praying to a priest named Padre Pio,” his wife said. “I have been invoking his presence so that he will protect me against your drunken rages.” Later, she admitted that she had sewn a picture of Padre Pio inside Giovanni’s pillow case. His wife’s words aroused his curiosity. He got in his taxi and made the long journey from Tuscany to San Giovanni Rotondo. He had to find out if Padre Pio was the same man that he had seen in his bedroom.

When Giovanni arrived at the little church of Our Lady of Grace, he noticed many people standing both inside and outside the church with rosaries in their hands. The sight of it was disgusting to him. He assumed that they were all religious fanatics. Giovanni had very little respect for people who claimed to have faith. He had always considered religion to be a matter of superstition. As an active member of the Communist party, Giovanni had spent years persecuting people who professed religious faith.

Giovanni was standing in the sacristy of the church when he saw Padre Pio for the first time. He immediately recognized him as the man who had stood beside his bed. “So, the mangy old sheep has arrived!” Padre Pio said when he saw Giovanni. It was definitely not a warm welcome.

Giovanni wanted to speak to Padre Pio privately. Ever since he had the strange experience of seeing Padre Pio in his home, he had begun to think about the meaning of life. If faith was important and if God really existed, Giovanni wanted to discuss the matter with Padre Pio. He was told that the only way to do so was to go to confession to him. He decided to take the plunge.

In the confessional, Giovanni was shocked to hear Padre Pio say to him, “You must leave at once. I cannot hear your confession. You must find another priest. I do not want to go to hell for you!” After hearing the harsh words, Giovanni had no peace of mind. He was angry at Padre Pio for speaking to him in such a cutting manner, but after a short time, his anger subsided. He desperately needed some answers to his questions and he felt that Padre Pio was the one person who could supply them.

Giovanni felt at a total loss as to what to do next. He could not bring himself to make his confession to another priest. He had heard that Padre Pio’s parents, Grazio and Giuseppa Forgione were buried in the local cemetery. He walked to the cemetery and was able to find their graves. He wanted to say a prayer to them but he did not know how to pray. He had never said a prayer in his life. Instead, he lit two candles, one for Grazio and one for Giuseppa. He spoke to them from his heart, “You are Padre Pio’s parents. Please tell your son to accept me as one of his spiritual children. I want to change my life and I also long to hear a kind word from him.”

One morning, after Giovanni attended Padre Pio’s Mass, Padre Pio spoke to him briefly. He tapped Giovanni on the head and said to him, “It is not true what you were thinking in the church today, ignoramus! I want you to learn how to pray the Rosary!” Obediently, Giovanni went and bought a little devotional book with instructions on how to pray the Rosary.

Not long after, Padre Pio heard Giovanni’s confession. For the sins that Giovanni had forgotten, Padre Pio named them for him. During his confession, Giovanni broke down and cried. Padre Pio cried as well. Giovanni handed his Communist party membership card to Padre Pio and asked him to throw it away. Padre Pio said, “Yes, that is good. I will indeed destroy it.” Giovanni invited many of his former Communist friends to visit the monastery. He introduced them to Padre Pio and many were converted.

Padre Pio explained to Giovanni that he had hurt a lot of people and needed to make amends for his past sins. He told Giovanni that he must go to the last Mass each Sunday until further notice. At that time, the fasting rules of the church were such that one had to fast from midnight until the time one received Holy Communion the following day. That meant that every Sunday, Giovanni would have to fast from the previous night until the end of the next day.

Everyone without exception went to Sunday Mass in the morning, in part because of the strict fasting rules. People were generally quite hungry after fasting from midnight the night before. They usually went directly home after Mass in order to have breakfast. No one received Holy Communion at midday or at the end of the day. For Giovanni, not only was the penance difficult, it was also humiliating. As he walked down the aisle to the communion rail all by himself and knelt there alone, he felt embarrassed. He had to endure the rude remarks of the people in the church who whispered together about him and stared at him curiously.

Giovanni’s penance lasted for almost one year. He never asked that the length of time be shortened and he completed it without a complaint. At the end of the year, he spoke to Padre Pio and told him how happy he was that his penance was finally over. Padre Pio said to him, “Giovanni, I too suffered during that year. I was stretched out on the cross and I shed my blood for you.”

Giovanni wanted to live his new found faith to the fullest. He knew that Padre Pio was interceding for him and helping him to turn away from sin. Most of his destructive behaviors fell away easily. He stopped using profanities in his speech and he made many other positive changes in his life. There were a few bad habits, however, that he found difficult to break. He spoke to Padre Pio about it. Padre Pio said to him, “Giovanni, you put in your good will and I will take care of the rest of it.”

Giovanni visited the monastery as often as he could. Sometimes he would reflect on his life and say to himself, “Why am I so captivated by this elderly priest? Why have I left everything for him?” Giovanni knew in his heart that he would never return to his former way of living. On several occasions, while sitting in the little church of Our Lady of Grace, he had seen Padre Pio’s face shining with an unearthly beauty. He asked one of the pilgrims if he had ever seen the radiance on Padre Pio’s face. “Indeed I have seen the same thing,” the man replied. Giovanni spoke to Padre Pio about it. “Father, your face is so very beautiful.” “Why would you say something like that to me?” was Padre Pio’s only reply.

One day at the monastery, Giovanni was present when Padre Pio and some of his fellow Capuchins were talking together. The subject of Padre Pio’s stigmata came up. “Tell us how you received the stigmata,” one of the Capuchins said to Padre Pio, but he made no reply. Several of the Capuchins gave their opinion on the matter and each one had a different idea. “It was the crucifix in the choir loft of the church that imprinted the wounds of Christ on Padre Pio’s body,” one of the Capuchins stated. “And what do you think happened, Giovanni?” Padre Pio asked. “I have a different thought about it than the others,” Giovanni replied. “I think that Jesus came down from heaven and embraced you. At his embrace, you received the stigmata.” “You are closer than all of the others in your explanation,” Padre Pio replied. But he would make no other comment.

John McCaffery had an adventure with Giovanni da Prato on one occasion that he would never forget. One day, he happened to see Giovanni at the monastery. Giovanni told John that he had a great desire to see Padre Pio that day. “Oh, but it is impossible,” John replied. “Padre Pio is sick and confined to his cell. No one is allowed to visit him today.” “I will tell you a secret if you promise not to tell anyone,” Giovanni said. “I happen to have a key that leads to the monks’ cells.” “How on earth did you manage to get a key?” John asked. But Giovanni would not answer the question. “Don’t worry about how I got the key. Let’s just try our luck!” Giovanni said.

Giovanni’s bold and daring spirit gave John the courage he needed to do something that was very much against the rules. The two men walked past the “no visitors allowed” sign in the monastery and unlocked the door that led to the cloister. They walked down the hall very quietly so as not to arouse attention and then opened the door to Padre Pio’s cell. Once inside, they saw that Padre Pio was all alone. They spent just a few moments with him. Padre Pio received them kindly and gave them each a blessing. Giovanni had received his heart’s desire.

On one occasion, John told Padre Pio about a brand-new book that had just been published in Ireland. “What is the book about?” Padre Pio asked. “It is a book about you,” John replied. At John’s words, Padre Pio became distraught. With tears in his eyes he said, “You are the ones who are good. Not me. I know that God has given me many graces. But it frightens me to think about it because I do not think that I have made good use of the gifts that I have been given. I think that anyone else would have made better use of them than I have.” John tried to convince him otherwise but he was not able to change Padre Pio’s mind.

During John’s visits to the monastery of Our Lady of Grace, he came in contact with a number of people who had received miracles through the hands of Padre Pio. John witnessed some of the miraculous cures with his own eyes, including the complete healing of a man who had throat cancer. The pain of the man’s illness was intense and he was only able to speak in a hoarse whisper. As his disease progressed, his speech became completely inaudible. It even became difficult for him to breathe.

The man and his wife had moved from Milan to San Giovanni Rotondo in order to be close to Padre Pio. Every day, he stood in the sacristy, waiting for Padre Pio as he passed through the sacristy to the church. When Padre Pio came into view, the man would simply look at him and in silence, he would pray to him for healing. But the man’s faith was put to the test. He had been suffering from the disease for over a year, and his condition was growing steadily worse.

One evening, when the man was in bed and trying to sleep, the pain of his disease became intolerable. He had the sensation that he was suffocating. Try as he might, he could not seem to get enough air. He became so desperate that he got out of bed and went to the monastery. The monastery door was locked, so he rang the bell. When one of the Capuchins came to the door, the man pleaded with him and said, “I have to see Padre Pio. I am very sick and I need his help!” “But the church is closed for the night,” the Capuchin replied. “Padre Pio is in the choir praying his night Office. No one can speak to him at this late hour. You must come back tomorrow.”

The man’s pleadings finally touched the heart of the Capuchin and he led him to the choir loft where Pio was praying with the rest of his religious community. At once, Padre Pio saw the pitiful condition the man was in and got up from his prayers and walked toward him. Weeping, the man threw himself on his knees before Padre Pio. Padre Pio then placed his hand on the man’s head in a blessing. At Padre Pio’s touch, all of his pain disappeared. He felt an intense joy coursing through his body. The feeling was so overwhelming that he did not think that he could endure it. He wrenched himself away from Padre Pio and stood up. Padre Pio evidently was aware of the blessing that the man had received for he smiled at him and said, “That surely was beautiful, wasn’t it! But now you must go back to your home and go to bed because it is late.”

Padre Pio later advised the man to have surgery in the city of Bologna and gave him the name of a highly-skilled doctor who could help him. The man followed Padre Pio’s advice and had the operation. The next time he returned to the monastery, his voice was strong and he had regained all of his former vitality. He said that the doctor had given him a clean bill of health. John was amazed to see the complete transformation in the man.

John was a witness to another miracle, which concerned a man from Lecco, Italy who was blind. The man visited Padre Pio and begged him for his intercessory prayers. The man knelt down and implored Padre Pio saying, “Even if sight returns to only one eye, I would be so grateful and so satisfied.” He kept repeating the words. Padre Pio answered him and said, “Do you want healing in one eye only?” Then Padre Pio promised the man that he would pray for him. The man’s eyes had a sunken appearance and John described them as looking like two “dried and shriveled peas.” The man received a miracle, for the next time he returned to the monastery of Our Lady of Grace, both of his eyes were completely normal in appearance. With tears of gratitude, he thanked Padre Pio for his prayers. An interesting fact of the story is that the man’s vision was restored in one eye only. Padre Pio spoke to him later and said, “Remember, do not put limitations on God. Ask him for all that you need. Always ask for the big grace!”

As John witnessed the healings around him, he reflected on his own poor health. He had a heart condition which caused him to experience heart palpitations and made him so uncomfortable that at night he had to sleep sitting up in a chair. He was frequently tormented by severe and recurring headaches. One night he lost consciousness and was rushed to the hospital. He had suffered a partial stroke. He often feared that he would die an untimely death and he worried about his wife and children. Who would provide for them if he should pass away?

One day at Padre Pio’s Mass, John prayed silently and with great intensity, begging Padre Pio to intercede and to heal him of his heart condition. That afternoon, John saw Padre Pio in the monastery. He spoke to John very tenderly and said, “I want you to know that my prayer for you is that you go to heaven. I want you to be satisfied with that. I ask you to pray for me as well, that I might go to heaven. Do you understand what I am saying?” “Yes, I understand,” John replied. He was disappointed at Padre Pio’s words but he tried his best not to show it. Padre Pio had obviously been aware of John’s prayers at the Mass that morning. His comment indicated to John that he was praying for his salvation, not necessarily for his health. Evidently, John was not going to receive a healing for his failing heart.

After speaking to John, Padre Pio continued to converse with the others who were present. John was preoccupied with thinking about the remark that Padre Pio had made to him. He was trying to hide his feelings of sadness. Several times that afternoon, John noticed that Padre Pio was staring at him with a very penetrating gaze. When it was time to say goodbye to Padre Pio, all the men who were gathered knelt down to receive his blessing. Once again, Padre Pio scrutinized John with great intensity. He blessed all of the men and then embraced John in such a way that John’s head rested on Padre Pio’s chest, near the wound in his heart. Padre Pio held John’s head against his heart wound for some time. It was the third time that day that Padre Pio had embraced John in such a way.

After Padre Pio departed, the others who were present told John how lucky he was. He had obviously been singled out for a special blessing that day. Some time later, Padre Pio placed the palm of his right hand against John’s heart. After that, John never again had any signs or symptoms of a heart condition. The next time he went in for a checkup, the doctor informed him that his heart was in perfectly good condition.

After Padre Pio’s death on September 23, 1968, John McCaffery never went back to San Giovanni Rotondo. He had visited Padre Pio countless times over a period of many years. With Padre Pio gone, John could not bring himself to return. He knew that it would not be the same. John had made many good friends in San Giovanni Rotondo. He was not to see any of them again. He went back to his home in Donegal, Ireland where he stayed for the rest of his life. John passed away in 1981.

________

“Death and eternity are the two faces of one great destiny. Nothing is in vain; nothing dies. Our life on earth is completed, crowned, and perpetuated in heaven. Earthly life is beautiful and worthy when it is lived in the service of God. All that is beautiful and good in us and around us on earth and in the universe is a mere pallid image of the kingdom of God. The higher one rises toward heaven, the more he understands the great mystery of life which has as its aim: goodness, happiness, God.” — Giorgio Berlutti

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

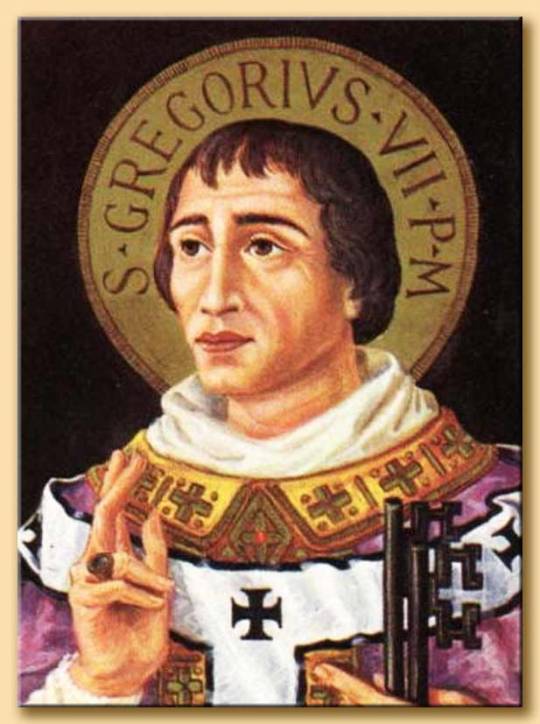

25 May – Today is also the Memorial of St Pope Gregory VII (1015-1085) Monk, Priest, Reformer, Administrator, Adviser, born Hildebrand of Sovana (Italian: Ildebrando da Soana), was Pope from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. Patronage – Diocese of Sovana. St Pope Gregory was born in c 1015 in Soana (modern Sovana), Italy and died on 25 May 1085 at Salerno, Italy of natural causes. Pope Gregory “was probably the most energetic and determined man ever to occupy the See of Peter and was driven by an almost mystically exalted vision of the awesome responsibility and dignity of the papal office” (Eamonn Duffy, Saints and Sinners: A History of the Popes.

A disciple of Pope Gregory VI

Born at Sovana, a small town in southern Tuscany, the son of a blacksmith and christened Hildebrand, he was educated in Rome by the archpriest John Gratian, who in 1045 became Pope Gregory VI. However, because of a financial deal involved in getting rid of his corrupt predecessor, Gregory was deposed in 1046 by the reforming German king and Holy Roman Emperor Henry III and went into retirement in the Benedictine monastery of Cluny, France. Hildebrand went with his master into exile at Cluny and spent three years there as a monk.

Ambassador of four popes

However, he returned to Rome in 1049 to serve the newly elected Pope St Leo IX as papal treasurer. Hildebrand became a deacon and then prior of the monastery of St Paul’s Outside the Walls and was an assistant to a major influence on the next four popes, all of whom were reformers. He was also successful in various ambassadorial roles. On the death of Pope Alexander II (1061-73, he was elected pope by popular acclaim by the clergy and people of Rome. He still had to be ordained priest and bishop before he could act as pope.

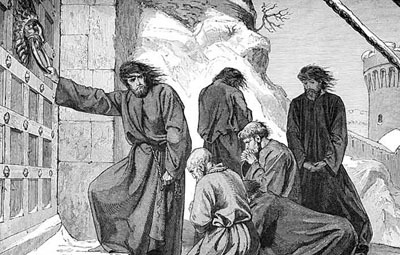

Conflict with King Henry IV of Germany

Taking his name from his mentor Gregory VI, Gregory VII immediately set about cleaning up the abuses of simony, clerical concubinage and lay investiture. He demanded that bishops take an oath of obedience to him and threatened those who wouldn’t carry out papal decrees. Over lay investiture he faced opposition from King Philip I of France, William the Conqueror of England and the young King Henry IV of Germany. Henry, whose father had appointed bishops and popes at will, resented the brusqueness of this new pontiff and gathered “his” bishops at Worms and insisted Gregory be deposed. But Gregory then excommunicated Henry and all the bishops collaborating with him and absolved his subjects from allegiance. Ecclesiastical support for Henry cracked and in 1077 he had to travel to the house of Matilda of Canossa in Italy where Gregory was staying and there he begged the Pope’s pardon and absolution. Gregory left Henry standing in humiliation for three days in the snow before eventually granting him pardon.

Pyrrhic victory and death

But Gregory’s victory was short lived. Henry rallied his forces and in 1080 invaded Italy, captured Rome, declared Gregory deposed. He installed an antipope Guibert of Ravenna as Clement III. Gregory took refuge in Castel Sant’Angelo, invited in the Normans under Robert Guiscard to rescue him. However, the Normans behaved so badly in Rome that the Romans turned on Gregory and forced him to retire first to Monte Cassino and then to Salerno south of Naples where he died. His last words were famously an adaptation of Psalm 44 (45) verse 7: “I have loved justice and hated iniquity; therefore I die in exile”.

Papal claims

Gregory’s pontificate represents a strong staking out of the papal claim of power over the secular world and though he achieved little, the spirit of papal reform continued and the papacy never receded from its claims to freedom from secular and political control in spiritual matters. From this time on also the pope began to be presented not just as the vicar of St Peter, but as “the vicar of Christ himself” (Innocent III 1198-1216).

His influence

Gregory’s beatification (1585) and canonisation (1605) took place at a time when the papacy was in conflict with secular powers – Queen Elizabeth I and James I in England. His feast was extended to the universal Church in 1728, causing some fury among proponents of Gallicanism in France.

He was later seen as a precursor of Vatican I with its definition of the doctrine of papal infallibility . One could perhaps be forgiven for detecting a hint of spin or ideology in his promotion but the tyrannies of the 20th century bear out the value of his insistence on the freedom of the Church in speaking out on spiritual matters.

(via Saint of the Day - 25 May - St Pope Gregory VII (c 1015-1085))

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas Nativity Sets: What They Are and Where to Find Them

Italy's culture still has a strong religious component. It is not surprising that Christmas plays such a significant role in Italian traditions. This is not because of the commercialism that you might see in other countries, but for all the right reasons. The spirit of giving and the optimism that anything is possible.

It's therefore not surprising that the nativity set is a major part of Italian Christmas culture.

In the middle of the 13th century, St. Francis created the first outdoor live nativity set in a cave close to Greccio's tiny Italian monastery. The nativity was used by St. Francis to tell the Christmas story to the local population, who were largely uninformed and could not have read it. It must have been very meaningful to the parishioners that all the major characters were played by local people.

The Christmas nativity set was born. Many small Italian villages still have live outdoor nativities. The idea of re-creating an indoor nativity for festive decorations was quickly adopted by western Europe, despite it being originally an outdoor scene. It is one of few Christmas traditions that has survived both time and culture. It's now called the 'creche' in France, the kribbe' in Germany, and the UK the 'crib'. In Italy, it's called the 'presepe' (plural of both being ’presepio).

The Christmas nativity set is a crucial part of any Italian home, from early December to the feast of Epiphany on the 6th of January. Families treat their nativities like family heirlooms that they start collecting as young couples and then add to each year with the hundreds of presepe' figurines purchased in shops and markets across the country, most famously in Rome’s Piazza Navona in November.

Fontanini is the preferred manufacturer of high-quality Italian Christmas nativity sets. It is a family-owned and operated company. The company was established by Emanuele Fontanini, a local businessman, in a small room in Bagni di Lucca in Tuscany in 1908. Fontanini has grown, but it still specializes in hand-painted nativity figurines. It is a great honor to work with them. Some of the best painters in Italy are employed by the company.

Fontanini produces some of the most well-known indoor Christmas nativities. Recently, they have introduced a range of snow globes. A 10" tall, 14" wide set made of a nearly indestructible, child-friendly resin that is hand-painted is one of their most popular.

You can also make beautiful outdoor nativity scenes. These lawn nativities have become increasingly popular in both private homes and in public places such as churches and government buildings. They can hold figures up to 48 inches high and are sculpted with the same Fontanini care to detail. Although the figures aren't cheap, you can buy one piece at a time to make an outdoor nativity set.

It's not enough to have a stable scene. In Italy, a "proper" Nativity is more than just a single scene. With pizza-makers, wine sellers, and electrically-operated water-mills, the scenes quite often spill down a homemade "hillside", each little scenario telling the story of life carrying on while a miracle is happening close by.

Fontanini Christmas Nativity/Crib Sets make great gifts for young couples. It's not only for Christmas but also for weddings and anniversaries. The nativity is a family tradition that becomes part of every year's family activities, with some of the figures being collectible. It is a treasured reminder of the family's Christmas traditions.

0 notes

Photo

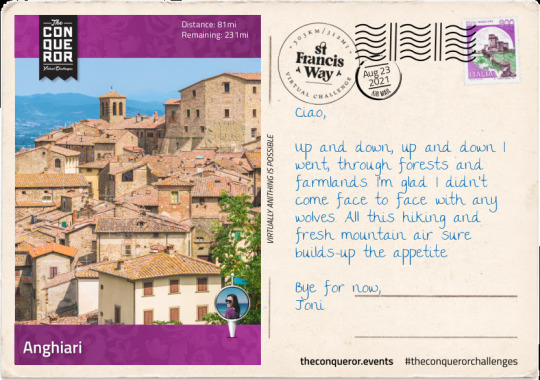

POSTCARD 03 @ Anghiari

The trail continues weaving through mountains and forests passing a few isolated buildings to the mountain village of Badia Prataglia. The village is located within the Foreste Casentinesi, a national park that stretches out over 37,000 hectares. It has more than 600km of trail paths and 20 mountain biking routes. The area can also be explored on horseback, whilst in the winter it is open for cross-country skiing. In the village is a mid-19thC arboretum that was originally established for Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany. The arboretum has a museum that also includes the Duke's former villa.

Skirting around the small village of Rimbocchi (1,640ft/500m), I am back in the woods admiring the tall trees, densely packed as I gently climb up to La Verna (3,937ft/1,200m) to visit the Franciscan sanctuary where St Francis is said to have received the stigmata in 1224. The sanctuary is home to several churches, chapels and a monastery. The site was taken under papal protection in 1260. The main church took over a century to complete from 1348 to 1459. The monastery was partially destroyed in the 15thC, suffering desecration during the war of this time and it took three centuries to be fully restored. The friars suffered further in 1810 and 1866 when they were expelled from the monastery as part of suppressing religious orders.

The sanctuary is nestled within a spruce-beech forest with specimens as tall as 160ft (50m) and some with diameters up to 5.9ft (180cm). The forest floor teems with wildlife such as deer, boar and wolf, whilst above one can find eagles, owls and peregrine falcons.

Leaving the sanctuary, I descended through fields and farmlands to Caprese Michelangelo (1,969ft/600m), a small commune where Michelangelo, a Renaissance era painter, sculptor and architect was born in 1475. Michelangelo was baptised in the village's church, St John de Baptist and a museum in his honour has been established inside a fortress. The aim of the museum is to document his body of works with plaster casts. The collection also includes sculptures and paintings donated by artists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The terrain steadies a little with gentle undulations until I reached Anghiari, a sprawled out, hilltop town overlooking the Tiber Valley. The town centre, however, is a fortified collection of stone buildings and labyrinth-like narrow streets. In this compact location are a handful of museums including the Battle of Anghiari Museum. The battle was a 1440 event between the Republic of Florence and Duchy of Milan. The battle, comprising of thousands of foot soldiers and knights took only one day and according to Machiavelli it resulted in only one death of an unfortunate knight who fell off his horse and drowned in a swamp. The battle ended with the Florentines winning and securing their domination over central Italy. Leonardo da Vinci depicted a painting of the battle which has since been lost. Fortunately copies existed inspiring Paul Rubens to sketch a replica of the original.

The terrace in the town centre with its fortified wall was a perfect place to indulge in some Tuscan food, overlooking the landscape and residential homes. My starter was bruschetta which was a slice of Tuscan bread generously rubbed with garlic, lavishly drizzled with green olive oil and lightly sprinkled with salt (at home I might have chopped up some tomatoes and added it to the mix). This was followed by a hearty slow-cooked stew called "spezattino" and finished it with a scrumptious sugar-coated, fried doughnut known as "bomboloni". No meal experience is ever complete without a café macchiato.

0 notes

Text

Sangiovese Di Romagna Wine

Sangiovese di Romagna is probably Emilia-Romagna’s best known wine, though for a long time likely for the wrong reasons. More on that in a bit. The story goes that the name of the grape originated from Sant’Angelo di Romagna at a Capuchin monastery. A noble guest was visiting the monastery and remarked at the quality of the wines made from the hillside Collis Jovis vineyards. When he asked what the wine was called, the name Sanguis di Jovis (Blood of Jupiter) was made up on the spot. From there it evolved from Sangue di Giove and finally to Sangiovese in the 18th century. Its popularity through the decades gave Sangiovese di Romagna the distinction of becoming the region’s first DOC in 1967.

The large production zone stretches from the hills east of Bologna to the coast of Rimini, with various subzones inbetween. To be labeled as Sangiovese di Romagna, the wine must contain at least 85% Sangiovese and up to 15% of other grapes grown in the production zone. There are four styles Read more »

Sangiovese di Romagna is probably Emilia-Romagna’s best known wine, though for a long time likely for the wrong reasons. More on that in a bit. The story goes that the name of the grape originated from Sant’Angelo di Romagna at a Capuchin monastery. A noble guest was visiting the monastery and remarked at the quality of the wines made from the hillside Collis Jovis vineyards. When he asked what the wine was called, the name Sanguis di Jovis (Blood of Jupiter) was made up on the spot. From there it evolved from Sangue di Giove and finally to Sangiovese in the 18th century. Its popularity through the decades gave Sangiovese di Romagna the distinction of becoming the region’s first DOC in 1967.

The large production zone stretches from the hills east of Bologna to the coast of Rimini, with various subzones inbetween. To be labeled as Sangiovese di Romagna, the wine must contain at least 85% Sangiovese and up to 15% of other grapes grown in the production zone. There are four styles:

*Sangiovese di Romagna - the catch all style, must be made from grapes in the production zone.

*Novello - “new wine.” 50% of grapes undergo carbonic maceration (like Beaujolais nouveau) with a minimum ABV of 11.5%. Meant to be consumed young.

*Superiore - grapes are grown in what are considered the top areas of the production zone, the hills south of Via Emilia. These wines must reach a minimum 12% ABV.

*Riserva - sourced from grapes grown at lower yields, aged at least two years before release. These wines are considered the most structured and ageworthy.

For a long time, Sangiovese di Romagna was the dilettante cousin of the more prestigious Sangioveses of Tuscany like Chianti Classico and Brunello. It has the same ripe cherry flavors, but with less of that tannic bite in most cases. This was the wine many red-checker table cloth Italian joints in the 60s, 70s and 80s served as their “house wine” in the straw carafe, usually a bit thin and unremarkable. But in more recent years, producers realized they had something to work with if they gave it a little love. These wines tend to have more perfumed qualities, and some herbal notes. One edge over Tuscany is they aren’t as acidic. Try one with your next pizza and see how well it matches the red sauce, bringing out the fruitier notes.

0 notes

Text

The Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

The Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore

A visit on a gorgeous day to the Abbazia di Monte Oliveto Maggiore in Tuscany is about as good a day trip as I can think of. Leaving Florence on a soft, summer morning, it is a pleasure to drive through beautiful countryside. And once you reach the historic abbey itself, you’ve reached a little piece of heaven.

This large Benedictine monastery is constructed mostly of red brick, making…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Un petit monastère en Toscane / A Little Monastery in Tuscany

Otar Iosseliani. 1988

Hitchhiking

Strada Provinciale della Badia di Sant'Antimo, 53024 Montalcino SI, Italy

See in map

See in imdb

#otar iosseliani#un petit monastere en toscane#a little monastery in tuscany#hitch hiker#monk#road#movie#cinema#film#location#google maps#street view#montalcino#siena#tuscany#italy#1988

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cinque Terre & San Gimignano

On Saturday (4/29), I got up very early to go to Cinque Terre with my mom, Patrick, and Grandmama! We did a tour group, and took a bus that first brought us to one of the 5 terres, but we just passed through there briefly before taking a train to Manarola. Patrick and I decided to walk up to this church at the top of a hill that had a great view of all the pretty colored houses and the water. My mom and Grandmama walked around below and looked at the shops. We took lots of nice photos, went inside the church (I swear every church in Italy looks VERY similar), and then walked down to the water. We climbed on these rocks, but had to be careful because they were really wet and slippery. It was nice being with just Patrick. He’s finally getting to the age (15), where I can actually have real conversations with him and we really get along now. I love his adventurous spirit-just like me! He kept saying how amazing Italy was and how he wants to study abroad. I told him the biggest thing I learned this semester was that traveling and never getting to comfortable in one place, always having the urge to see the world and what it has to offer, is a beautiful thing. He seemed very interested and agreed with me, and it made me smile. We then got on a boat to Monteresso. The boat ride lasted about 45 minutes, and let me tell you, it was 45 minutes too long. Yes the view was great, and it was a nice day, but the water was SO choppy. People were puking or close to it all around us, and I was not feeling too hot. Finally the boat ride ended and we got off to have lunch that was included with the tour. The lunch was great! It started with a fish salad that was delicious, then pasta with a pesto sauce. We were laughing because we didn’t realize the train passed right over the restaurant, and when it came the first time, the noise was so loud we thought there was an avalanche of some sort. The guy at the table next to us actually stood up and looked panicked, which freaked us all out! After we were all laughing, though. After lunch, we started to make our way to the Old Town part of Monteresso, because that is where our tour guide said we needed to meet to go to our next destination. We had to pass over this cliff, either by going through a tunnel, walking up some stairs and crossing over, or by walking up even higher and going across, where you could see a monastery. We decided to take the highest route, and after we saw the monastery, we aren’t really sure what happened but we could not figure out how to get across! It was hot and we could tell my mom and Grandmama were getting tired of just aimlessly walking, so we finally just turned around and took the lower way across. The view from up there was worth it to me, though! Once we got across, we got gelato and then it was time to get on a train to Vernazza. We were a little disappointed because once we got there, we only had 45 minutes before we had to leave, and the tour guide said we should try to go to the bathroom before we leave. We spent our whole time in Vernazza waiting in line for the bathroom! It was a zoo with so many tourists. We had to get on a train for about 20 minutes to La Spezia, where we got back on the bus. Overall, I thought Cinque Terre was beautiful, I just thought the organization of the trip could have been better, and I wish we had a little longer in Monteresso and Manarola. When we got back, I brought the fam to Gusta Pizza, which is some of the best pizza in Florence. They wanted to go to a sit down restaurant, but it just wasn’t possible on a Saturday night with no reservation (didn’t think about how there are so many tourists now-wouldn’t have been a problem a couple months ago!). I had made reservations for the weekend before, but Gusta Pizza had to do, and we got lucky enough to get a table, which is rare. I walked them back to their hotel, and then met them again in the morning for an early breakfast at their hotel. Saying goodbye to them was sad, but I’ll be home in not too long now! I spent Sunday on a vespa tour through the hills of the Chianti region of Tuscany, and it turned out to be one of my favorite days of the whole semester. We (me, Autumn, Atticus, Alyssa, and Jamie) met in Florence, and had to take a van with a few others. We stopped at Piazzale Michelangelo to take photos, and although I’ve been up there many times, I’d never seen it so clear. We got back in the van and went to the place where we got on the vespas. Riding them at first was hilarious, it’s such a strange feeling to get used to! It’s kind of like riding a bike but a little harder to balance, and you have to get the gas just right because if you give too much you will lose control. After practicing a little bit, we headed out to ride to San Gimignano, which is a medieval city with high towers in Tuscany. We stopped along the way to take pictures, and it was so so beautiful and open. The feeling of riding through the hills with the wind in your face was amazing, and I felt so so happy. When we got to San Gimignano, we spent 30 minutes walking around and exploring the city with our vespa guide. Then, as part of the tour, we got gelato, and it was some of the best gelato I’ve had in Italy. We ate it while looking out at a panoramic view of the region. I loved San Gimignano!! We got back on our vespas, stopping again for photos every once in a while, for about another hour or so before going back to the starting point where there was also a restaurant and Tuscan winery! We knew our tour price included lunch and a wine tasting, but we did not expect this! We tasted NINE different wines (with a hefty pour each glass), balsamic, and olive oil. The food was delicious, too, and the restaurant overall was just so cute and aesthetically pleasing. We had an amazing day riding vespas, and then it ended with wine and food, who could complain!? Alyssa was a volunteer at one point and one of the guys in the family that owns the winery, Leonardo, ended up kissing her on the cheek a few times…you definitely had to be there to understand. He was cute. After all that, we popped a bottle of champagne for a couple that was on their honeymoon, and another couple that plans to get married in a week in Lake Como?. It was really sweet, and the perfect ending to the day. We got back in the van to ride back to Florence, all feeling ourselves, and the driver played the best throwback music. We had so much fun singing and dancing the whole way back. What a great weekend!!!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wine 101: Sangiovese/Chianti

This episode of “Wine 101” is sponsored by Brancaia. At Brancaia, we perceive the work in the vineyard as a flow of energy that must be respected to the highest degree. Rooted in the bold super Tuscan movement that forever changed Italy’s winemaking culture, the wines of Brancaia blend local grapes with international varieties, bringing a decidedly modern touch to a centuries-old wine region. Today, Brancaia embodies a passion for terroir and dedication to artisan techniques, producing elegant, complex wines with a strong Tuscan identity. Brancaia Winery: Resist the usual.

Click the link below to discover and purchase wine brands discussed on the Wine101 podcast series. Get 15% OFF when you purchase $75 or more. Use coupon code “wine15” at checkout: www.thebarrelroom.com/discover.

In this episode of “Wine 101,” VinePair tastings director Keith Beavers discusses the origins of Sangiovese and Chianti. Beavers discusses the history of Sangiovese from its origins in Tuscany, as well as its many nicknames. However, what listeners will learn most about is Chianti, the popular wine made from the Sangiovese grape.

Beaver explains how Chianti came to be a central winegrowing region in Italy, dating back to the 18th century, and how it rose to popularity in the 1970s — appearing in popular films such as “Shaft” and “Silence of the Lambs.” Further, Beavers explains the emergence of the Chianti Classico DOCG in the late ‘80s.

Tune in to learn more and become an expert on Sangiovese and Chianti.

Listen Online

Listen on Apple Podcasts

Listen on Spotify

Or Check out the Conversation Here

Keith Beavers: My name is Keith Beavers, and I think I’ve watched all of HGTV. Like, all of it. I need something else.

What’s going on, wine lovers? Welcome to Episode 19 of VinePair’s “Wine 101” podcast, Season 2. My name is Keith Beavers. I’m the tastings director of VinePair. Sup?

Chianti and Sangiovese. Oh my gosh. You know it from a movie, from life as an American, and from loving Italian wine. Let’s talk about it.

OK, so we did an episode on Tuscany last season. It was to get a nice, rounded idea about Tuscany, and in that episode, we talked about Sangiovese and we talked about how it’s different. It produces different styles of wine, depending on where it’s growing in Tuscany. It’s a very interesting variety, but it’s not an interesting variety in that it mutates and it clones itself and all this stuff. No. What’s unique about Sangiovese is that there are really two kinds of Sangiovese. There’s Sangiovese Grosso, a big fat grape. Then, there’s Sangiovese Piccolo, a little grape.

The majority of the wines that we drink come from Sangiovese Grosso, the big fat grape. But the thing is, Sangiovese Grosso grows throughout Tuscany, but the people who produce wines from that grape call it something different, even just in Tuscany itself. In Montalcino in Tuscany, they call Sangiovese Grosso, Brunello. In the town of Montepulciano, where they make Vino Nobile di Montepulciano, they call it Prugnolo Gentile. And in the Tuscan region of Morellino di Scansano, they call it Morellino. It can be confusing. I know I say it a lot in wine. It can be confusing. Why is wine so confusing?

Well, the thing is, wine is ancient. Oh my gosh, it’s so ancient in so many cultures, townships, and communes throughout Italy, throughout the world. All the synonyms for the grapes, it’s just insane. The thing is, during feudal systems and sharecropping, there is pride in all these towns. It seems to me that they name the grape, and they could care less whether another town calls it something else. This is what they’re going to call it. And that’s just how this works throughout the history of wine in general. In Tuscany, it’s a little bit crazy because it went from one town to the next. Sometimes the variety that’s being used is the same variety but has a different name. And it can be crazy.

Just like other old varieties like Pinot Noir, Sangiovese is thought to be ancient. The first documentation of Sangiovese is from a treatise on the viticulture of Tuscany in 1600 by a dude named Giovan Vettorio Soderini. In it, he says, “il sangiogheto, aspro a mangiare, ma sugoso e pienissimo di vino” which generally means “the Sangiogheto, bitter to eat but juicy and venous.” This is the first documentation of Sangiovese but it’s really the first documentation of the synonym of Sangiovese.

The story goes that, in the region of Emilia-Romagna, which is north and east of Tuscany, there is a town called Rimini. Just outside of that town is a mountain called Montegiove. And in the foothills of that mountain was a — wait for it — monastery! Yep, the monks. And here, the monks were making wine. And the wine they made, they called vino, which basically just means wine in Italian. When asked what this wine was, they thought for a second and they said “sanguis Jovis”, which means the blood of Jupiter. Sangiovese came from that.

Eventually, it’s thought to be also a reference to the blood of Jove. Sangiogheto is a synonym of whatever happened there. Sangiovese isn’t only important in Tuscany. This whole story happened in a region just outside of Tuscany. Sangiovese is really the workhorse of central Italy in general. In Umbria, it is blended in a DOC or a wine region called Montefalco. It’s often blended with a grape called Sagrantino, a very big, powerful variety that softens it a little bit.

In the region of Le Marche, there are two very well-known red wines there, Rosso Piceno and Rosso Conero, and they are also Sangiovese, blending with a grape called Montepulciano. Not the town, but the grape. It’s also being used more and in Lazio, which is where Rome is. And here’s a fun little fact, if you guys ever come across Corsican wine — yeah, we should sometime do an episode on Corsican wine. It’s pretty cool. They make wine from Sangiovese there. But there they call it Nielluccio. Yeah, it’s crazy. It’s good and it’s awesome. They do great rosés with it, too.

Now every town, every region that produces wine from Sangiovese is awesome. Everyone has their own unique spin on this variety. It’s beautiful, and that’s all in the Tuscan episode. Yet, what you and I know more than any other wine made from Sangiovese in Italy is Chianti. This wine has had a presence in our culture for a long time. I remember as a kid, in the early ‘80s, going to this Italian restaurant with my parents. They loved it so much, it was called Mom and Pop. They had basket wine bottles. They’re called fiaschi. There were Chianti bottles with the baskets on them, and that was the candleholder.

Even as far back as the ‘70s, it made it into film. You have “Shaft,” an amazing film. When Shaft goes in to talk to the local Italian crime boss, the dude is sitting there sipping on a nice Chianti. I mean it was a basket wine, but in the ‘70s, it was considered good stuff. Of course, we had to get this out of the way: “A census taker once tried to test me. *I ate his liver with fava beans in a nice Chianti” — creepy murder doctor Hannibal Lecter, “Silence of the Lambs.”

Yeah. I don’t know where you are in age or pop culture, but that scene is one of the most famous scenes from the movie and one of the most famous scenes in film history. And what’s really interesting is in the book, he has this fava beans with the liver, with an Amarone, which is actually a red wine from the northern part of Italy. But because Chianti was so ingrained in our minds, the people writing the script decided to put Chianti in there instead of Amarone so we would be familiar with it. Sure enough, that line is basically timeless.

And even though we, in the United States, have had an intimate relationship with Chianti for such a long time, it still confuses us. It’s confusing because, guys, Chianti is complicated. It’s really complicated. If I had an entire episode to tell you the history of this place, it would blow your mind.

The city of Florence, which is very close to the Chianti wine region — which we’re going to get into in a second — I think between the 14th and the 16th century was the center of the world. This is where the birth of the Renaissance happened, some of the most famous glassmakers in the world were in Florence. The stories, the history, and the documentation are pretty immense. Just the story of Florence and its history with its rival city just to the south, Siena, includes Chianti and the wines from this region. These are awesome stories for another time because we’re here to talk about wine. Let’s get deep in the hills of Chianti and understand this place.

In the center part of Tuscany, there is a major town called Florence, which you guys all know. And then south of that city is a city called Siena. Between the town of Florence and the town of Siena, are these mountainous hills there called the Chianti or the Chianti Hills or the Chianti Mountains. It’s thought that viticulture goes all the way back to the Etruscans, which came before the Greeks. Actually, the Greeks came to Italy, and they saw the Etruscans. The Etruscans freaked out the Greeks because of their hedonism. It’s wild. I just wanted to tell you about that.

I mention the Etruscans because I’ve always been so fascinated with the word Chianti, in that I don’t know what it means and it’s very hard to figure out what it means. The only thing I could really find is that the Etruscans are thought to name this area, Clante. I don’t know what that means, but Clante? Chianti? It makes sense. If anybody knows any Italian etymologists that can help me out, would be awesome. However, the word Chianti first shows up in documents in the late 1330s. That seals the deal for Chianti. Well, the name at least because this document doesn’t name wine so much, it just calls this area the Chianti Hills.

By the 18th century, this area was known for wine. There are three townships in the Chianti Hills: Castellina, Radda, and Gaiole. At this time, Chianti was applied to these three townships. Also what’s interesting is these three townships are under the jurisdiction of Florence, and they formed what was called the League of Chianti, which was a guard against the town or city of Siena at the time. There was a rivalry, and a pretty storied rivalry at that. If you remember in the Portugal episode, we talked about the Douro Valley and how it was one of the first attempts at demarcating or creating some controlled appellation because of the popularity of the wine to combat fraud and to maintain the authenticity of the wines coming out of that region because of all the money that was being made there.

This is the same thing that happened in 1716 in the Chianti Hills. The three initial townships — Radda, Castellina, and Gaiole — were demarcated as Chianti, the wine-growing and winemaking region, by Cosimo III, the Grand Duke of Tuscany. In these hills with high-ish elevation in this very well-known famous soil called galestro with some limestone and clay, there’s a short list of native varieties that are being used to make wine around this time — most of them red, some of them white, often blended together for red. You had Sangiovese, there was a grape called Ciliegiolo, which is actually related to Sangiovese. Also, there is a grape called Mammolo and a grape called Canaiolo. Those are the red wine grapes. For white wine, there’s a group called Trebbiano, which is all over central Italy, and a grape called Malvasia, which we’ve mentioned before in other previous episodes.

There wasn’t a rhyme or reason and there weren’t any rules or regulations. Toward the end of the 19th century, there was this dude named Baron Bettino Ricasoli. In 1872, he wrote a letter saying that he had synthesized 10 years of experimentation. And what he’s found is that the Sangiovese grape is the best grape to use as the base of the Chianti blend. For aging wines, he found that Sangiovese’s aroma profile and its vigorous acidity, blended with a little bit of Canaiolo, was the best way to make age-worthy Chianti. For younger wines, he kept that little formula going, but he thought, “You know what? Add a little bit of Malvasia. Add a little bit of white wine. It really is nice.”

This formula or this idea caught on. And basically, this guy — and his family still makes wine to this day — is the inventor of modern Chianti. From the 18th century to the 1930s, this is what Chianti was: three townships basically carrying the Chianti name, but it’s spreading out more and more. People started to adhere to this new Chianti formula. The identity of Chianti was coming into itself. By the 1930s, this wine was becoming very popular, so the Italian government decided they were going to extend the Chianti zone. They’re going to name different subzones to capitalize on what was happening here. And to the dismay of the original townships, the government extended these subzones to basically surround the original area.

To this day, there are seven of them. Chianti is the prefix, and then the geographical location comes after that. I’m not going to get into all of them, but I’m going to name some of them right now so you can get a sense of them. Colli Fiorentini, Rufina, Montalbano, Colli Aretini, Colline Pisane, and Montespertoli. And you’ll often see it on the wine label. It’ll say Chianti in big letters, and underneath it it’ll have the geographical location. This extends the Chianti zone to about 40,000 acres, give or take. It’s a very large area.

In the 1960s, when Italy was creating its own appellation-controlled system that was based on the French appellations system, they went to Chianti and they saw how popular the ricasoli formula was. When they gave Chianti its DOC, that is the blend that became a regulation for Chianti: Sangiovese, Canaiolo, and Malvasia. They also added other varieties in there: Mammolo, Ciliegiolo, and also Trebbiano. With such a large area and with some economic troubles in the region, the trend of Chianti wines went towards quantity, not quality. Of course, there was quality being made during this time, but until the early 1980s, it got pretty bad as far as people taking advantage of a good thing. The famous Fiaschi basket wine we see in “Shaft” was eventually seen as just not very good wine. It was very thin. There was a lot of white wine in it, and it was giving Chianti a bad rap. To this day, Chianti basket wine is mainly known as a candle holder. Am I right?

And it wasn’t only basket wine that was compromised. There was a lot of wine coming into the United States and just being distributed throughout the world in which the quality wasn’t there.

In 1984, the government said “OK, we’re going to elevate the Chianti region from a DOC to a DOCG. We’re going to have stricter rules put in place. Now, we’re restricting the amount of white wine you can use and doing all these things to make sure the quality of Sangiovese is sound.” And I gotta say, they made some good decisions.