#Timothy O’Sullivan

Text

Is Cruelty the Price of Peace? — Another View on Gaza

The Gaza war has produced over 13,000 corpses so far, most of which were civilian non-combatants, including thousands of women and children. The ratio of Palestinian deaths to Israeli deaths is 10 to 1. Ten eyes for an eye.Enough!

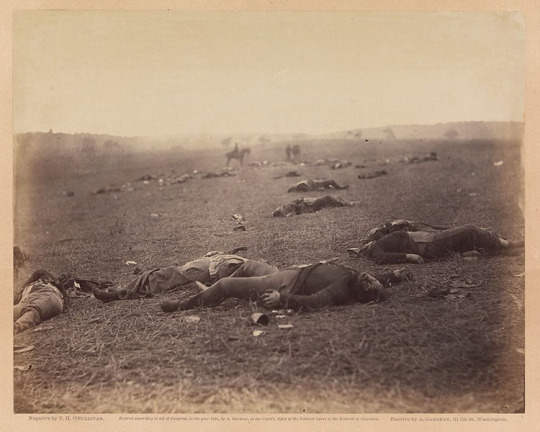

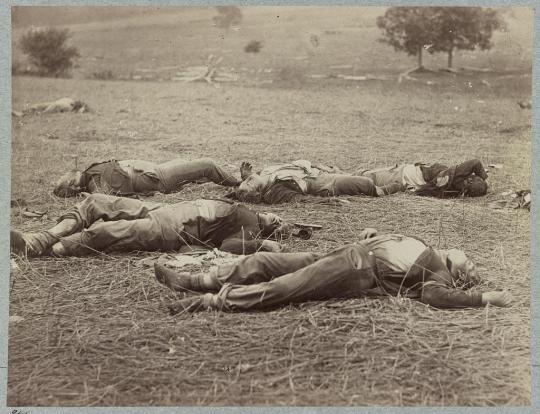

Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Harvest of Death (Gettysburg, July 1863: the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War).

“War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.”

— William Tecumseh Sherman, 1864

“I confess, without shame, that I am sick and tired of fighting—its glory is all moonshine; even…

View On WordPress

#American Civil War#Book of Ruth#Carthaginian Peace#Cynthia Bourgeault#Ezra#Gaza#Israel#kenosis#Orson Welles#Palestinians#Robert Alter#San Gimignano#Stephen Crane#The Hebrew Bible#War in Gaza#William Tecumseh Sherman

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

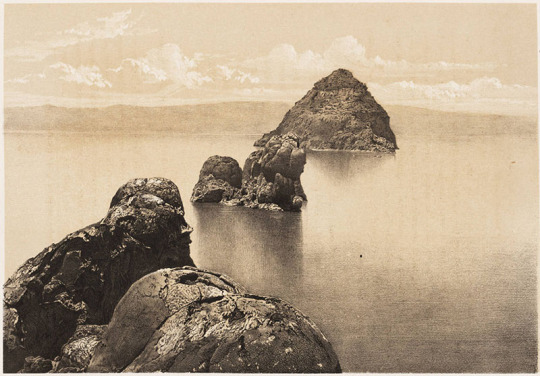

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American, 1840-1882), The Pyramid & Domes, Pyramid Lake, Nevada 1867, Albumen print Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

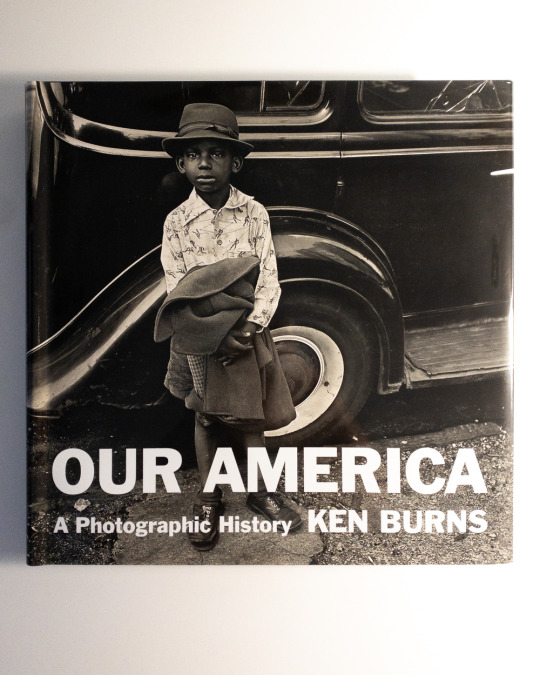

I’ve been waiting two years to share this news. I’m not really sure how this came to be, but certainly it is a highlight of wishing my work out into the world. 26 years ago in a crowd of many I could not take my eyes off a dancer at the Schemitzun Powwow and, I think for the first time in my life, approached a stranger to ask for a portrait. This is what we made together, “Tommy in His Car”. And now it is in this stunning new book, Our America, A Photographic History, by Ken Burns with an introduction by Sarah Hermanson Meister. Oh, and it is on the facing page of an image by Sally Mann, and just page widths away from the iconic works of Hansel Mieth, Elliott Erwitt, Minor White, Walter Iooss, Richard Avedon, Danny Lyon, Eve Arnold, Dennis Stock, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Gordon Parks, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson, Jerome Liebling, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, Eudora Welty, Helen Levitt, Marion Post Wolcott, Walker Evans, Margaret Bourke-White, Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler, Alfred Stieglitz, Laura Gilpin, Lewis Hine, Edward Curtis, Mathew Brady, Timothy O’Sullivan, and Carleton E. Watkins. There are many more known and unknown photographers, but these are the names that leapt out at me when I finally got to hold the book in my hands last night.I’m kinda excited! Many thanks to Tommy Christian, Ken Burns, and Susanna Steisel.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Contemporary Views Along the First Transcontinental Railroad

While construction of the Pacific Railroad ostensibly began during the Civil War, it was not until that great conflict was over that it really got rolling. In a race for government subsidies and land grants, the Central Pacific built eastward from Sacramento, California, while the Union Pacific built westward from Omaha, Nebraska. The two railroads met at Promontory Summit, just north of Great Salt Lake, Utah Territory, on May 10th 1869. It was a watershed moment.

I follow in the footsteps of photographers Alfred A. Hart and A. J. Russell who expertly recorded the construction of the road. But this is not a re-photography project—it is, rather, photography as archaeology. In making a comprehensive series of photographs along the original route, my goal is to give the viewer as strong of a connection as possible to this 19th century engineering marvel through the remaining visual evidence of the human-altered landscape. And while not visible, I also hope to evoke the various peoples involved with the railroad, as well as those affected by it.

~ ~ ~

I have always been drawn to western landscape photographs, particularly the work of Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan. I tend to see their imagery as existing on opposite sides of an aesthetic coin—with the former rendering the beautiful and the latter portraying the sublime. These two 18th century linguistic terms, beautiful and sublime (usually considered in relation to one another), were used to categorize one’s emotional response when viewing artwork. Imagery that promoted pleasurable and familiar feelings was referred to as beautiful, while pictures that evoked feelings of awe or terror, often brought on by the immense scale of nature, were referred to as sublime.

The story of the first transcontinental railroad is one of contradictions and oppositional forces not unlike the conceptual interrelatedness of those two aesthetic terms. The surveyors explored an Eden, but initiated its destruction. The road was a crown jewel of the industrial age, but the actual building, the grading and tunneling, was done almost completely without machines. The railroad conquered time and space, but this led quickly to the decimation of the American bison which pushed the people who depended upon them to the brink. This was the first transcontinental railroad in North America, or anywhere for that matter. The pounding of the Golden Spike signaled the completion of a great human achievement, but it must have sounded like a death knell to Native Americans. It put a bow on Manifest Destiny and served as a primer for the questionable business practices that would follow in the Gilded Age.

~ ~ ~

In the end, I want these images to be a pictorial accompaniment to well-established textual histories of the building of the railroad, the foremost being David Haward Bain’s Empire Express. His book tells the complete tale, but when I’m in the field I most often think of the people who built the line with their hands and their backs—primarily the Chinese, who performed so well for the Central Pacific, and the Irish, who toiled proudly for the Union Pacific.

The railroad is still active over much of the route—which was preceded by pioneer trails, joined by the Lincoln Highway, and eventually succeeded by Interstate 80 and air travel. While I have photographed along much of the line, I tend to linger where the steel has been pulled up, those portions of the line that has been abandoned for a less steep or curvy alignment. I enjoy the calm of those deserted areas most—through modern absence, I find it most easy to imagine a 19th century presence.

Richard Koenig, Genevieve U. Gilmore Professor of Art, Kalamazoo College—see forty web-based images here from across the route—from west to east.

#railroadhistory#railwayhistory#firsttranscontinentalrailroad#unionpacific#centralpacific#pacificrailroad#transcontinentalrailroad#americanwest#westernlandscape

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Puget Sound on the Pacific Coast, Albert Bierstadt, 1870

“Through more than 100 works, including an in-depth presentation of the Seattle Art Museum’s painting Puget Sound on the Pacific Coast (1870) by Albert Bierstadt, Beauty and Bounty surveys great 19th and early 20th-century American landscape paintings and photographs, showing American artists’ responses as they encountered the North American continent’s ever-expanding vastness of natural beauty and nature’s bounty. The exhibition presents a rare opportunity to view great works of American art that have rarely—or never—been seen by the greater public.

Painters including Sanford Gifford, Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran gave form to landscapes of once unimaginable character, as they crossed the continent on expeditions through the plains and the mountains of the Great West. Beauty and Bounty includes 45 of these majestic works—many of which are held in private collections and were previously unknown to the public. Also included in the exhibition are approximately 60 landscape photographs, including mammoth plate images by the pioneers of the western photography, including Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and Timothy O’Sullivan.

The paintings and photographs on view demonstrate that it was often these artist-explorers who were raising important questions about humankind’s place in the world and how best to respond to a continent that many at the time viewed as a divine blessing of beauty and bounty from nature.”

–Patricia Junker, The Ann M. Barwick Curator of American Art, Seattle Art Museum

#missing seattle today so I'm looking through some Seattle Art Museum exhibits online#puget sound#seattle#trees trees trees#peering through

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did J.E.B. Stuart’s Vanity Spark the Gettysburg Campaign?

Culpeper was a key supply depot on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, which ran from Alexandria, on the outskirts of Washington, D.C., to Gordonsville in Orange County, Va. In August 1862, photographer Timothy O’Sullivan placed his camera directly on the track to capture this photograph of a stopped freight train. (Library of Congress)

This article by Robert Lee Hodge was in the August, 2023…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Official Poster For THE MIRACLE CLUB | In Theaters July 14 | Starring Laura Linney, Maggie Smith, Kathy Bates, Stephen Rea, Agnes O’Casey

Sony Pictures Classics has released these official poster and trailer for THE MIRACLE CLUB starring Laura Linney, Maggie Smith, Kathy Bates, Stephen Rea, & Agnes O’Casey

IN THEATERS JULY 14, 2023!

*World Premiere – Tribeca Film Festival 2023*

Directed by: Thaddeus O’Sullivan

Starring: Laura Linney, Kathy Bates, Maggie Smith, Stephen Rea, Agnes O’Casey

Written by: Jimmy Smallhorne, Timothy…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Gold Hill Nevada

Gold Hill, Nevada is a small unincorporated community located in Storey County, Nevada, United States. It is situated on the eastern side of the Virginia Range, about 10 miles south of Reno. The history of Gold Hill dates back to the early 1850s when gold was discovered in the area.

Gold Hill, Nevada Circa 1867, 1868 Photographer Timothy H. O’Sullivan

The discovery of gold in Gold Hill is…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

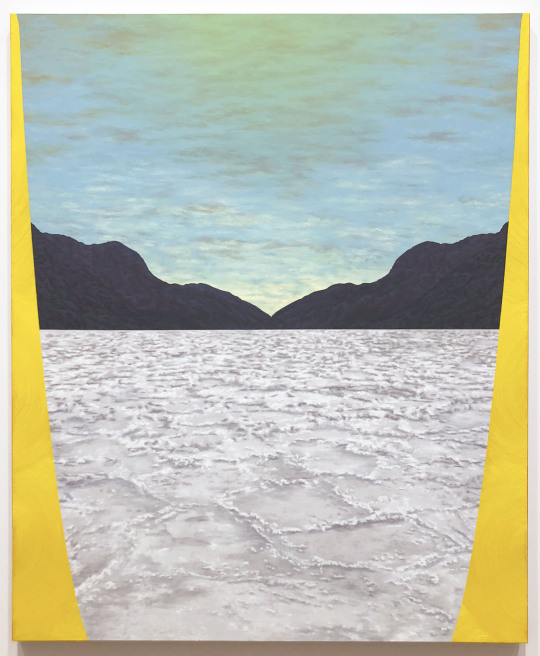

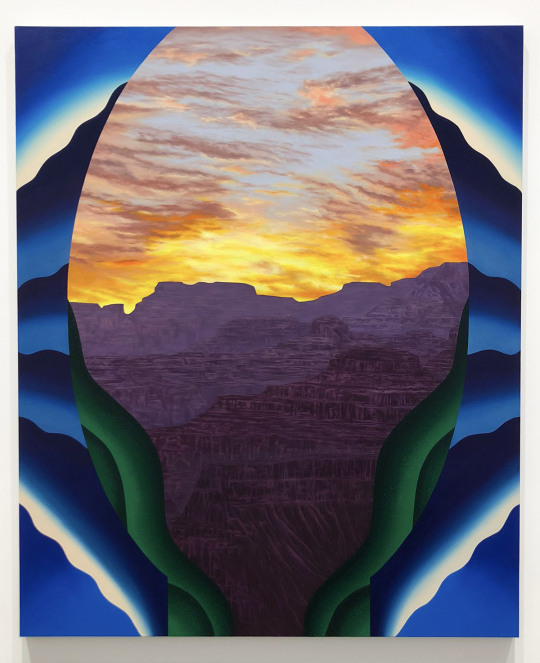

Closing on 3/11/23 is Joani Tremblay’s exhibition of paintings, Intericonicity at Harper’s gallery in NYC.

From the press release-

Tremblay presents twelve oil paintings made since April 2022 that largely depict the landscape of rural Pennsylvania. In contrast to the chromatic levity of recent work portraying citrus fruits or the American southwest, here Tremblay hews to a darker palette of rich greens and blues inspired by farmland valleys just thawing at the start of spring. This is what she saw driving from New York City through the Laurel Highlands to reach Fallingwater, the iconic house that Frank Lloyd Wright designed as a nature retreat for a wealthy retail magnate.

How we use the land lies at the heart of Tremblay’s work. A road’s placement, a water reclamation initiative, or the machinations of land ownership matter for Tremblay not so much for their factual circumstance as for the power relations that structure them. Behind the myths of the untouched landscape or nature as a fierce inevitable conqueror over human ambition lies a question about our standpoint when we approach a particular vista. Will we simply look? Take a photograph, or retrieve a rock to carry with? Commission a plan to shape the earth this way or that? Wright erected Fallingwater over a waterfall so that it literally straddles but symbolically surmounts the tributary’s onrush. Even its windows are unframed, the better to create an illusion of coextension with the same nature it tames. Built from 1935–39, at the height of the great economic depression, Wright used nearby laborers, supporting the local economy to forge an elaborate private gem amid the picturesque.

In this vein, contradictory impulses about our treatment of the land fuel Tremblay’s paintings, which are, for the most part, each made of three constituent components painted in the following order: sky, ground, and internal frame that focuses our vision like an aperture on the landscape beyond. In Untitled (rain), ice blue shards interpose themselves between roiling clouds anchored by the slender arcs of an emerald frame, while a flaming sky tops amethyst buttes seen through the undulating rays of a cobalt-green opening in Untitled (violet mountains). Tremblay works in oil, building up the texture of certain parts of her internal borders through varying degrees of thickness applied with a loaded sponge, in contrast to the smooth finish of those borders’ flat gradients and the medium texture of her landscape’s painted fields. But as her framing devices and the near-realism of her depictions of earth suggest, the discourse of photography undergirds her work conceptually.

In the nineteenth century, government-funded photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan spread westward, scrutinizing the earth. One of his images records a measuring stick alongside a text left on Inscription Rock by a Spanish invader, literalizing the human desire to regulate nature. Though Tremblay’s landscapes at first seem to aspire to such precision, she deploys lossy processes in the studio that encourage a departure from the indexical, supposedly truthful exactitude of landscape photography. Tremblay projects a digitally-mocked-up composition onto her canvas, but by using a poor-quality projector, she ensures that the image is too grainy to copy fastidiously at close range. And although she initially sourced one of her favorite skies—visible here in Untitled (rain)—from John Constable, she has painted it so many times that it has become her own via the minute changes materialized through repetition. She looks to her own work, not Constable’s, when she paints this sky anew. Thus, Tremblay charts a middle path between photography’s documentary dream and landscape painting’s glorification of subjective experiences in nature, drawing on these themes to surface accrued ideologies latent in the very notion of the landscape view.

Although Tremblay’s vistas arise from her personal travel, they seem uncannily familiar because they draw from a cultural imaginary rather than from specific locales. To wit, Tremblay conducts research on Instagram, where curated landscapes are already shot through with aesthetic codes long established by artists from Ansel Adams to Lawren Harris and Arthur Dove. Photography’s indexical referentiality is at a remove twice over in Tremblay’s work, first through the interpretive act of painting by hand, and second by encoding within it a whole set of images and conventions for their appearance that encircle us in the digital realm.

Unlike a palimpsest, in which a first layer of representation is covered over by a second, Tremblay’s work operates through intericonicity, a term derived from semiotics. Intericonicity offers a way to understand a relation of copresence between two or more images which may appear eidetically or actually as one image within another. This realm of infinite reproduction and false memory offsets a more straightforward mood each painting’s chromatic scheme seems to deliver. The smooth, inky valleys of Untitled (sunset and trees) might suggest placidity, for instance, the sheer height of Untitled (Laurel Highlands) soaring power. But because each work signals allusions to so many art historical or geographic references alongside their ideological effects, that mood resists resolution. Said differently, these are not easy paintings to decode. Their sharpness of focus functions on multiple strata at once.

#joani tremblay#painting#harper's#harper's gallery nyc#intericonicity#landscape painting#john constable#timothy o'sullivan#ansel adams#lawren harris#arthur dove#art#art shows#nyc art shows

0 notes

Text

An appreciation post for my favorite Civil War Era photographer: Timothy O’Sullivan

View on Apache Lake, Sierra Blanca Range, Arizona, with Two Apache Scouts in the Foreground 1873, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Iceberg Cañon, Colorado River, Looking Above 1872, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: Smithsonian American Art Museum

Alpine Lake, in the Sierra Nevada, California 1871, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Cereus Gigantus, Arizona 1871, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Black Cañon, Colorado River, Looking Above From Mirror Bar 1871, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: J. Paul Getty Museum) if you look closely at this picture, you will see a small box on the boat. That box was needed to create the photographs. At this time, film hadn’t been invented yet so the pictures needed to be developed right away. Since Timothy O’Sullivan was out in the middle of nowhere, he couldn’t go to a studio to develop it so he built his own dark room on his boat (similar to the Whats-its wagons of the American Civil War).

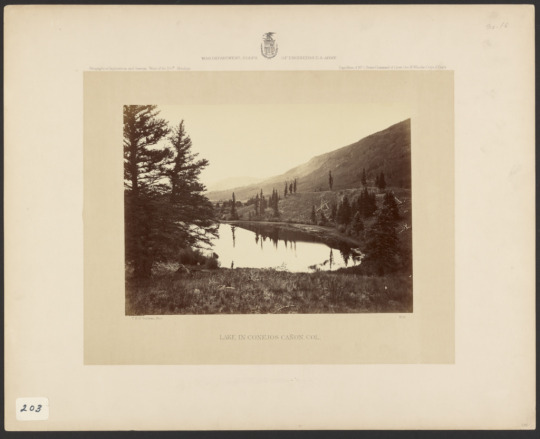

Lake in Conejos Cañon, Colorado 1874, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Washakie Bad Lands, Wyoming 1872, albumen silver print (Courtesy of: Library of Congress)

#yes I know#you probably thought it was Mathew Brady#but it isn’t#history#american history#us history#early photography#photography#Timothy O’Sullivan#desert#exploration

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

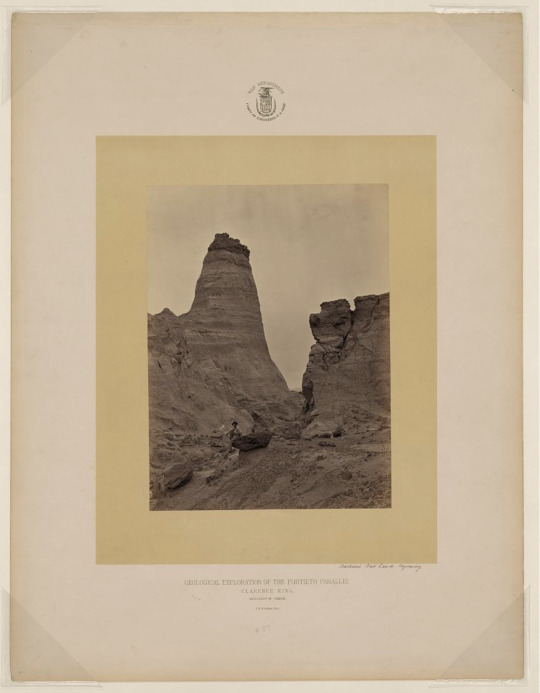

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American, 1840-1882)

Buttes near Green River City, Wyoming

1872

Albumen print

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

115 notes

·

View notes

Photo

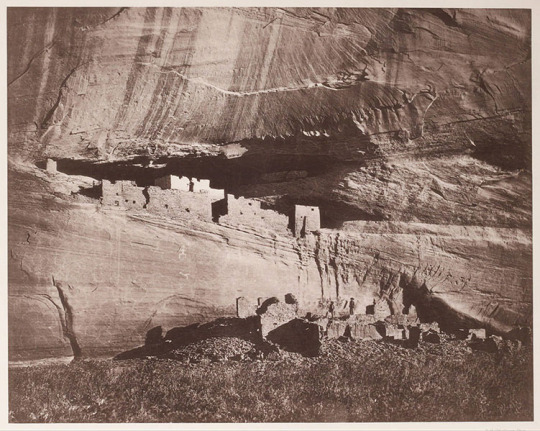

Timothy O’Sullivan – Scientist of the Day

Photographer Timothy O’Sullivan (first image), born c. 1840, died on January 14, 1874.

read more...

#Timothy O’Sullivan#Photography#Geology#Civil War#Clarence King#Fortieth Parallel Survey#19th Century#History of science#Histsci#Scientific illustration

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Timothy O’Sullivan (1867) Turfa Domes, Pyramid Lake, Nevada

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dead soldiers on the Battlefield of Gettysburg, PA - July 1863. Photo by Timothy H. O’Sullivan [1024x785] Check this blog!

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882) - Desert Sand Hills near the Sink of Carson, Nevada (1867).

source

97 notes

·

View notes