#TV Criticism

Text

Torchwood: Children Of Earth is my favourite alien invasion story of all time, and here’s why:

The series portrays an accurate depiction of how governments would realistically respond to such a crisis. A lot of media tends to portray governments suddenly ‘banding together against a common enemy for the greater good’ which while it’s nice to believe we would do so to defend our home planet, the response to the climate crisis shows that’s a laughable naive and simplistic view of how the institutions in our society operate.

Instead in children of earth, the UK governments sole concern is to secure its own interests and cover its tracks to deflect and obscure any culpability they have in how the events unfold or any responsibility they have to protect their people. In perhaps, the best scene in the series, the government coldly and dispassionately discusses trading over 10% of the nation’s children as livestock. The 10% they consider to be the least valuable members of society, the least deserving of the state’s protection because they are the least useful to the state’s interests. All while their own children are exempt, of course.

It uses the trope of the alien invasion to strip away all the pre-tense of government and reveal the system for what it truly is. The sci fi elements allow the scene to remove the language of euphemisms so often used by politicians and reveal what the state truly trades in. The stock of human lives. The whole series serves to highlight how the institutions that claim to protect us are in fact the biggest threat to our safety in the modern world. All of it wrapped in the bow of one of the most tense and engaging political thrillers I’ve ever seen.

*chef’s kiss* it’s truly Russel T Davies masterpiece and it’s downright criminal that it’s not more widely known or critically acclaimed.

#torchwood#children of earth#russell t davies#rtd#tv#tv shows#tv criticism#essay#alien invasion#can’t lie#seriously considering turning this post into a video essay#but I just had to put this somewhere.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The West Wing episode 4.20 "Evidence of Things Not Seen"

Have you ever noticed how the biggest names behind the camera tend to have close relationships with a handful of actors who are in everything they make? Aaron Sorkin is no exception, and honestly, I feel like I understand why. His work is so specific, just like Tarantino’s or Scorsese’s, and when you have such an identifiable style, I think it either clicks with you or it doesn’t. When you find people who click with you, whose brains meld seamlessly with yours, it really is a euphoric feeling and I imagine you’d want to keep those people close.

The West Wing, and Aaron Sorkin, click with me. Sometimes I watch a show and the thrill is having no idea what’s about to happen; I’m along for the ride in a vehicle that I barely recognize, let alone know how to drive. I would never be so bold as to think I could have taken the wheel of The West Wing, but to keep the comparison going, putting an episode on feels like getting into your mom’s car. You know all its little nuances, where the cupholders are, and how it’s going to feel on the road (and when to grab the handlebar).

“Evidence of Things Not Seen” has everything I love about The West Wing; it’s a fun one, but an inspiring one too, and it even guest stars- get this- Matthew Perry, fresh off of Friends. All the characters are mostly off the clock in this episode, so it’s time for a good poker game. Leo and the President are excited to kick back over a game of cards; Leo even has a full spread prepared, and tbh nothing makes me laugh like his reverent demand of CJ to “oooh squeeze this piece of rye bread”.

But the relaxation will of course be interrupted. The President will have to step in and out to negotiate with Kaliningrad- their government spotted an unmanned spy plane that we were flying over there, and Bartlet needs to talk them into giving it back. Our cover story: it was an environmental mission studying coastal erosion (Chinese spy balloon anyone?). Josh will have to do some back and forth too, interviewing a candidate to replace Ainsley Hayes as associate counsel.

Amid all of this, it’s the equinox, and CJ is convinced that at “the exact moment of the equinox” you can stand an egg on its end, and it won’t tip over. She’s carrying an egg around, but she hasn’t pulled it off yet and skepticism abounds.

All of Sorkin’s characters speak with what’s become his trademark cadence and tone so at times I see them as somewhat interchangeable- he just likes the sound of a group. But “Evidence of Things Not Seen” highlights the individual personalities and ideological differences that actually are present and consistent once you get past the similar speech pattern.

We’re launched into the title sequence with Bartlet giving the egg thing- and this coastal erosion cover story- a shot, but the egg topples over. His subsequently loaded “yeah, this isn’t gonna work” is about a lot more than the equinox. Compared to CJ, he’s always been a pragmatic optimist, entertaining every romantic idea but not expecting all of them to pan out. CJ, meanwhile, will always stick her neck out to vouch for the idealistic solution, even when it’s not even in the realm of realistic. She’s also usually right. In a previous episode, when everyone else guessed that the president’s approval rating had remained the same at best, she wagered that they had gone up 5 points, a number so preposterous Leo wouldn’t even repeat it to the President. Turns out she was lowballing. She’s also the voice of the iconic line “it’s about going to the blackboard and raising your hand- if you think you get it wrong sometimes, why don’t you come down here and see how the big boys do it.”

Toby’s even more complex than either of them, which I’d go so far as to say is the reason he also has the most complex individual relationship with almost every other character. He and Bartlet are a story for another day, but Toby and CJ’s deep, often wordless friendship really run wild in this episode. Toby’s created the image of himself as the pessimistic curmudgeon, but it’s a defense mechanism for the red hot idealism he’s carrying around. He’s so often disappointed, and he’s tired of it, but he can’t help but see so much potential in the world, even if he won’t admit it.

Will’s being in the Air Force won’t come up again after this episode, but it comes up in this one to serve the theme of Toby and CJ’s dueling worldviews. He’s heading to Wyoming to address a situation in which two launch crew officers who were slow to react to a threat of an incoming missile from North Korea. Turns out it was a good thing they asked some questions before enacting protocol, because it wasn’t a missile- it was a meteor from space. But they’re still being court-martialed because if it had been a missile, they wouldn’t have reacted in time. Toby can’t help but burst out laughing at this story (“Why do we think at this point that North Korea is attacking the East Coast of the United States?” “There are transcripts that show that surprise was expressed at that”). Then he turns it on CJ: “We failed on both a mechanical and human level. So tell me again what you have faith in”.

“Us. Because with what little free time he has, Will is going to Wyoming to defend one of these guys, and I don’t think it is failing on a human level”. Instead of responding, Toby lays down his cards, expecting to win the hand. But, in another symbolic move that speaks to a lot more than poker, CJ lays out a full house, sweeping up the chips in her unexpected win.

While this weighty discussion hung in the air, Will, Toby, and CJ had another thing to attend to- a bet amongst men that the other couldn’t hurl a playing card into the podium from the fifth row in the press room. They head down there, with CJ tagging along hoping to see them both fail- no one’s taking her very seriously tonight, after all. Instead of settling that debate, they’re interrupted by three gunshots slamming into the press room window. Will’s military training kicks in and he drops to the floor and rattles off ballistics to the secret service agents that instantly burst in, but CJ freezes. It’s Toby who pulls her to the ground in the heat of the moment.

I don’t love this being the second time CJ’s been “saved” by a man in this show (Sam did the same thing at Roslyn), but this interaction with Toby feels a lot more organic than that did, and so does the way they address it. On the whole, everything about an active shooter and subsequent crash of the building is a tired plot at this point. I’d actually go as far as to say this entire episode is pretty unoriginal- a criticism I read when doing some research on this episode. But I think the familiarity of the situation is exactly the thing that gives this episode that fun, cozy, President-in-a-sweatshirt feel. We’ve done the defcon 1 “can you believe it?!” active shooter plot before, so now we’re able to have some fun with it (“fun” on The West Wing is a relative term).

The secret service herds Toby, CJ, Will, and Josh into the oval office to make sure there’s eyes on everyone. Charlie and Debbie are already accounted for, but they don’t have code word clearance, so they’re not allowed in the Oval, where the spy plane discussion is still ongoing. At least, according to the Secret Service. Bartlet good naturedly explains that “if Charlie heard there were bullets, he’s gonna overpower whoever’s trying to—” and he’s cut off by Charlie, sure enough, bursting into the room. The President grins, we grin, he pulls Charlie in close and promises he’s okay. Satisfied, Charlie marches right back out. Then Bartlet says “I’m surprised you guys managed to keep Fiderer in her chair, I’d have thought she’d be the first one to- oh no here we are!” as she too fights her way in the room, looking the President up and down and declaring that she will be back to take his blood pressure shortly.

In a beat amidst the commotion, CJ asks Toby if he knew that a day on the moon and a year on the moon were the same thing. He did. The moment hangs there. Then she says, “I thought my reflexes before, in the press room, were cat-like.” And then we cut away. I love how little we have to say in this episode, and it’s our familiarity with these people, these rooms, and this situation that really let us all just play here in “Evidence of Things Not Seen”.

And nowhere is this episode having more fun than it is with Josh and the unexpectedly incredible chemistry he has with Matthew Perry’s Joe Quincy. Throughout this entire episode he’s back and forth between advising the President and interviewing new associate counsel Joe Quincy. Joe is quiet, collected, funny, and overqualified, but something is off about him, and Josh can’t figure out what. In an aside to Donna, Josh muses that “it’s the strangest feeling. It’s like… a really good baseball player is standing in the other team’s locker room for the first time.” To which Donna says, “I don’t understand, are you writing poetry about this now?”

But his gut is onto something, and he’s trying to figure out what- amidst it all, though, he’s also starting to like him. Josh is amused that the vetting team made Joe fill out the psychological part of the questionnaire- something he can relate to, and I’ll come right back to that in a second. Josh asks a question I think we all probably wonder when filling out forms like this but have never thought to put into words:

“Question 1: a) I do not feel sad; b) I feel sad; c) I am sad all the time and I can’t snap out of it; d) I am so sad or unhappy that I want to kill myself. You chose a) I do not feel sad.”

“Yes.”

“Good. Ever?”

“No.”

“No, you don’t ever feel sad, or…?”

“No, there are times when I feel sad.”

“Yet you checked the first box, why is that?”

“It said, ‘I do not feel sad’ and I didn’t at the time I checked it.”

This exchange, and their whole dynamic, feels both funny and poignant, but the tables turn when the shooting happens in the very next scene. Donna is instantaneous in checking on Josh, worried about the shooting stirring up his PTSD and telling him, against his wishes, that she is going to be giving his therapist a heads up that he might be calling later.

When Josh explains the building crash to Joe, he says he didn’t hear the shots, but “I heard a brass quintet playing The First Noel, so I just assumed someone somewhere was locked and loaded.” Joe doesn’t hesitate to reply with “You know, not for nothing, but the people that I talk to don’t believe that story, and the people that you’d like don’t care.” He doesn’t say it unkindly, but like I said, funny and poignant.

But it’s not only the sentiment that throws Josh off, it’s the wording. Finally, Josh puts it together- Joe is a republican. Once his secret is out, Joe explains that he’s gotten himself in bad standing with the rest of the party by voicing an unpopular opinion, but he wants to work at the White House because, of course, he has a sense of duty. The whole thing is a soft, respectful, and incredibly loaded homage to both Ainsley Hayes and arguably the show’s best episode, “Noel”. And, just like Ainsley, Joe finds himself fitting right in, even as Josh tries to fight it. He recommends him to Leo and gets him the job.

I really love this episode for all the same reasons I think it often flies under the radar of West Wing greatest hits. It’s not remarkable, it’s not doing anything we haven’t done before, but it has its finger right on the pulse of every one of these characters. It’s exactly our deep familiarity with everyone and everything that lets the slightest touch hold so much significance, depth, and humor. It just takes half a sentence for a character to say something profound about another, or to call back to nostalgic characters and plot points. And I almost forgot to mention- we end with CJ standing an egg on its end. I well up every time.

#the west wing#evidence of things not seen#matthew perry#joe quincy#bradley whitford#josh lyman#allison janney#cj cregg#richard schiff#toby ziegler#martin sheen#jed bartlet#tww#josh malina#will bailey#tv criticism#tv review

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think that Night Country is honestly just OK as a season of television on its own but it’s still the second best season of true detective. And let’s be honest, the reason that the first season still reigns supreme isn’t because of its showrunner.

True Detective season 1 is amazing because of its performances and character work, not its direction. And it was fresh at the time.

I really hope that Night Country opens the door up for better tv. Better women and nb led tv. Please.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I miss supernatural being on. I feel like that's the one show I know everything about which made covering it weekly so fun. The most informed my tv episode reviews have been haha.

I'm going to tie this to how short tv seasons have gotten. When I was writing about Supernatural every week, there was so much show knowledge to fall back on that it made the reviews more fun to write. I mean, sure, Supernatural was already in season 12 when I started covering it, but having a show be on that long and have that many episodes in a season made covering it feel like an investment. It was so much fun.

I don't feel like shows last long enough anymore to hold deep knowledge of, like I did with Supernatural. Covering shows weekly that only have 8 episodes a season is fucking boring now. Especially if they do double or triple premiere episodes drops, then well, the season's practically half way over at that point.

Give me those long ass seasons back so I can write about them weekly like I'm trying to solve a fucking mystery or something. I want to track character arcs across 22 episodes again. I want to write about my favorite lines of dialogue or the narrative structure of an episode, or how an episode does meta commentary.

The closest I got to replicating my Supernatural reviews were my Roswell, New Mexico ones.But that show was a) not as good as supernatural, b) only had like 13 episodes per season and c) only lasted 4 seasons!!!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The ending of True Blood will never not be one of the biggest fumbles in TV history to me. This story started out as an exploration of non-traditional relationships, with heavy allegories both tied into racism and homophobia, morally grey characters, and open queerness!!

And where did we end up? Aside from the confusing mess that had once been a plot?

1. With Tara, the prominent queer black woman (also an abuse and SA survivor), dead, for the second time. They pulled the "bury your gays" trope twice. With the same character. A black woman. They really did that. The writers and producers really did that to her. Oh my fucking God. Tara, girl, I am so sorry. At least Lafayette survived (RIP Nelsan Ellis).

2. The Terry, the war veteran with PTSD, dead, in what was essentially assisted suicide. This lovable family man, who had his mind wiped by a vampire just so he could have some goddamn peace of mind, is then shot down just to give the audience a gut-punch.

3. Two of Sookie's supernatural lovers dead, including the main love interest, Bill. By Sookie's own hand, too. I guess that's at least a grand enough end to the main couple. There's something so symbolic about her literally killing her original connection to the world of vampires, I'll give them that. Maybe that would be a powerful ending to any other vampire story, but here in the world where vampires are a marginalized group fighting for their rights? Mmmm bad take.

4. The main characters in heteronormative relationships, with kids. We don't even know who Sookie is married to. Don't give me that "it's not about who she's with, it's about her being happy" crap. We have spent this entire series following this woman's romantic journey. It's kind of how this whole plot got kicked off. All that for her to be with some human guy we've never even met? What a slap in the face.

All those themes of accepting differences and finding true happiness outside of conformity, absolutely shit on. If I wanted to watch a show with Normal Happy Endings, I'd watch literally anything else. I hate it here.

#true blood#tv criticism#tv tropes#bury your gays#sookie stackhouse#eric northman#bill compton#tara thornton#lafayette reynolds#im so mad#one of the worst tv endings ever#seasonal rot#rant post#thinking about this will never not make me want to hurl a shoe at someone

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Masters of the Air - Part 5 Recap and Review (SPOILERS)

You're not going to find too many episodes of television as heavy as Part 5 of #masteroftheair, but it is 100% must watch. Terrence gives his thoughts on latest episode.

#Hollywood Already Did It#Masters of the Air#Callum Turner#Masters of the Air Part 5#Masters of the Air Part 5 Review#Episode Review#Master of the Air Spoilers#Apple TV#Nate Mann#YouTubers#tv criticism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reviewing the Pilot, “Rise of the Turtles,” of 2012 TMNT

The Plot

The first episode of the 2012 show starts with the four turtles training in battle. The show introduces Leonardo, Michelangelo, Donatello, and Raphael. In blue, we have Leo with katanas. Raph in red and with his sais. Mikey in orange as he uses his nunchucks to fight against Leo. Donnie has a bo staff and a purple mask. Already we can see their character reflected in the color of their masks and their choice of weapons, which I’ll address in another section.

It’s clear Ralph & Leo are the two best fighters. They beat their brothers in their 1-on-1 battles & go on against each other. At the end of their battle, Raphael wins & we meet Splinter.

Unlike the turtles, he’s a rat. Splinter is their sensei & their father. He seems wise & has plenty of authority.

In the kitchen, the family is celebrating their “mutation day,” aka their 15th birthday. Splinter goes into the backstory of their mutation & how they became a family. They have kept the canister that had the mutagen responsible for their mutation, which Mikey refers to as “mom.”

The four ask Splinter if they can go to the surface for their birthday, & after some hesitation, he allows it. This is where the real adventure starts.

As they wait for nightfall, Leo watches his favorite cartoon, Space Heroes. Often, the scenes in the cartoon illustrate the themes of the episode. Leo also dreams of being like the captain in the show. The others don’t find the show as appealing as Leo does.

Finally up top, they fall in love with New York City. This is where their love of pizza starts as they scare off a delivery boy who drops a pizza while driving off. As they jump from rooftop to rooftop, Donnie catches a glimpse of April O’Neil & falls in love.

At that same moment, she & her father get kidnapped. The four decide to help against Splinter’s wishes of staying away from humans. Although all of them are decent fighters, they have no chemistry with each other. The entire battle is a mess. Both April & her father get carried away by the mysterious cloned men.

The others go off & leave Mikey alone for a bit, then he makes a discovery. The men aren’t actually human; they’re robots with aliens controlling them. The viewer sees the other three don't listen to Mikey much. He is a bit ditzy and intelligence isn’t what he’s known for, but there’s a sense that they just see him as stupid. He’s ignored.

Back in the lair, they blame each other for why they lost the battle. Splinter explains that they weren’t prepared & the fault is his as he had not trained them as a team but as individuals. He considers not letting them back up until another year of training, but Donnie objects. As Splinter thinks about it, we see a photo of human Splinter with presumably his wife & child. This causes Splinter to allow the four turtles to go back to the surface & save April & her father. This is also when Splinter gives Leo the position of leader. Ralph is clearly upset about this decision.

The turtles stake out a spot that has the same logo as the van that kidnapped the O’Neils. Mikey doesn’t fully understand the plan, Ralph is doubtful, & Donnie is bored. Just as Ralph complains about how no one will show up, someone shows up. Leo mimics the captain from Space Heroes, but the others are already gone & starting the fight.

After chasing down the guy, they’re confronted with the same canister as the one they’ve preserved from their mutation. This is where part one of the pilot ends.

My Review

I’ve already completed the show, so this isn’t the first time I’ve viewed this episode. But this also gives me a different point of view as I’m already aware of all the characters & what everything leads to.

Going back to the color of their masks & weapons, we see that there is a connection between the personalities of the turtles & their colors and weapons.

Leo’s blue represents his trustability, dependability, and tranquility. These traits are why he’s picked as the leader. His weapon is widely known and a classic. It works for him perfectly as he easily beats Mikey in their 1-on-1 battle.

Ralph’s red shows his fiery and sometimes aggressive personality. His sais are weapons used for stabbing and striking but have a good defense too. Like his weapon, he’s an all-rounded fighter but prefers to be on the offensive.

Donnie wears purple, a color associated with individuality, creativity, and wisdom. This is clear as he’s the science guy of the team, which makes him useful but alienates him from his brothers as they couldn’t care less about science. His staff isn’t the best weapon, which shows that he’s not a fighter, but a thinker.

We see Mikey in orange. Orange is a color related to positivity, liveliness, and high energy. All the perfect descriptions of Michelangelo. His nunchucks also represent him well. Their origins are unknown and they were popularized through pop culture, which already seems like a Mikey kind of thing. They’re weapons that are difficult to use, as they can’t simply be swung around, but it’s obvious that they’re perfect for Mikey.

The characterization set up in this episode is a good foundation for what they later develop into. It shows the viewers the turtles’ personalities & dynamics of the team. For example, Ralph’s temper & Leo’s calm don’t go well together and that’s shown in this episode.

Splinter’s character is also expressed well. We even get to see some of his ninja skills when he tells the backstory. Throughout the entire show, I wished they would’ve allowed for some more of the fatherly aspect of Splinter to come through. It would’ve been nice to see this here in the beginning.

The plot of this episode isn’t the best in the series, but it’s good enough to drag you in. After it ends, you want to watch the next episode to find out if they save April, if they can work together as a team, and if they end up believing Mikey. You also want to figure out more about the strange alien robots and why they kidnapped the O’Neils. There’s also the canister of mutagen that the guy had that was the same as the one that mutated the turtles. It leaves plenty of intriguing unanswered questions that can only be solved by watching the next episode.

There was a good amount of light-hearted humor in there. The episode didn’t have me laughing until tears, but there were parts of it where I did laugh. Its action & adventure is fitting for children and fun to follow along with. One thing I didn’t like was how abrupt the kidnapping was, but once again, this is a children’s show. And that one trait didn’t ruin the entire episode for me.

Overall, I would rate the episode an 8 out of 10. Out of all 5 seasons, this wouldn’t make it in the top 10 for me, but it wouldn’t be anywhere near the bottom 10. It had good humor, adventure, action, and characterization. It was good, but not perfect.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

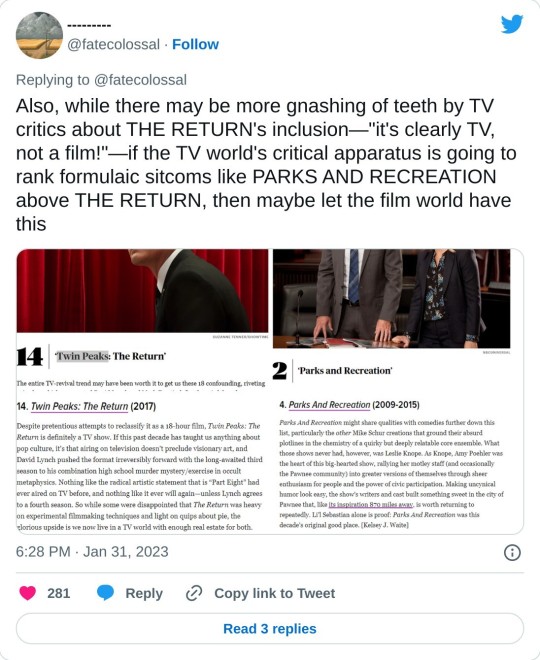

The Case for Considering TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN a Long-Form Film

That discourse you dislike is back in style.

“It truly is a film and anybody who would even venture to say otherwise, they’re mistaken.” – Duwayne Dunham, editor for TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN

“Categorizing TWIN PEAKS S3 as ‘a film’ sits in the same embarrassing school as labeling Ari Aster movies ‘Elevated Horror.’ People so embarrassed to adore something in a medium/genre ‘beneath’ their tastes they have to rewrite definitions to accommodate their own insecurity.” – viral tweet by A.B. Allen

With TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN being ranked #152 in the extended version of Sight and Sound's prestigious poll of "The Greatest Films of All Time" released a couple weeks ago, the old debate over whether it is ever appropriate to consider TP:TR a film, first begun after the work’s original release in 2017, surfaced for one more iteration. Although it is a small-stakes debate, seemingly only of importance for list-making, media beat assignments, and comparative academic analyses, it has proven to stir up some spirited opinions (and jokes). As in previous iterations of the discourse, many have expressed their difficulty at conceiving of TP:TR as anything other than a TV show. And it is easy to understand why the thought of TP:TR as a film strikes so many as preposterous:

It aired in weekly installments, usually about an hour or so long, and many of which ended in similar fashion, with a musical performance at the Roadhouse.

The communal experience, in the summer of 2017, of participating in weekly discussions about each new installment was quintessentially one associates with TV.

TP:TR’s length, at nearly 16.5 hours, far exceeds that of traditional feature films.

And more generally, there is a tendency at times for some to conflate the medium of TV with the formal artistic genre of TV shows, meaning that most things released on TV will have an uphill battle being considered anything other than (or in addition to) a TV show.

Yet there are also strong reasons for considering TP:TR to be a film, reasons that its lead-creatives pointed to after the work’s initial release as examples of how very different it was from TWIN PEAKS’ two TV seasons in 1990-91, and much more similar to their previous experiences working in film. For instance:

Notwithstanding the fact that TP:TR was broken into smaller segments for weekly airings, episodic form is of almost no importance to its structure, which was built as one long, continuous narrative.

Likewise, its production processes were focused on one single entity, the work as a whole, rather than being segmented into individual productions for each episode.

And it was entirely directed by the same person, and jointly written by the same two people, points that (along with the single production process) make it natural to attribute to it a unitary authorship more typically associated with films than episodic TV.

While it is true that TP:TR is not unique among works airing on TV (or streaming) in possessing these qualities, all this seemingly demonstrates is that other works face the same issues of category confusion; to the extent that it is determined reasonable for TP:TR to be considered a film and eligible for inclusion in film rankings like the Sight and Sound list, then these other works should likewise be eligible. While in practice it may often regrettably be the case that the only long TV works that end up being classified as a film are those “directed by people who are already beloved in the film world” (a concern expressed by critic Emily St. James), the remedy should seemingly just be an advocacy for more long TV works to be classified as film, using a more coherent, uniformly applied concept of formal artistic genres.

Given that the respected lead-creatives of TP:TR, veterans of both TV and motion pictures, have expressed at some length the above straightforward reasons for considering the work to be a film, one might have expected their reasoning to be at least acknowledged in the long-running online conversation on the issue. And yet, to read the back and forth over this on Twitter, one could hardly be blamed for concluding that the only real proponents of considering TP:TR a film are either snobs, trolls, or just wildly illogical—an outlook epitomized by the A.B. Allen thread quoted above, and by these other representative tweets:

(1). Snobs

(2). Trolls

(3). Wildly illogical

While I imagine that there are many reasons for this disconnect, I expect that it’s at least partly because, of the TP:TR creatives who have expressed a viewpoint on this, only David Lynch’s views seem to have been widely circulated, and people seem to be very willing either to dismiss his views as the illogical pique of a kooky individualist, or to suggest that he is driven by a snobbish view of TV (as critic Matt Zoller Seitz put it: “I think some part of him still feels that TV is a step down, no matter how much success he's had in it, and despite all he's done to expand its language”). It’s a shame that only Lynch’s brief remarks seem to have at all been paid heed, since other TP:TR creatives besides Lynch have been much more expansive in their remarks on the issue.

Episodic Segmentation vs Continuous Narrative

Take Duwayne Dunham, for instance. The editor of TP:TR, and a longtime veteran of both TV and film, Dunham stresses that its airing on TV has nothing to do with whether it should be considered a film (“television per se, it’s just the medium, Showtime”), and is adamant on one point: unlike the two seasons of TWIN PEAKS that aired in 1990-91, TP:TR was made with almost no attention to forming coherent and satisfying episodic units—a central aspect of how TV shows, as a unique art form, are often defined. “It wasn’t constructed or wasn’t written in that way (as television), it wasn’t shot that way, and it wasn’t cut that way. It was cut to be continuous.... [I]f you cut the titles off in-between episodes and just started with Parts 1 and 2, which came out as the pilot and you put them all together, you would not miss a thing. That’s how it was constructed.” This is, at least in part, why the show’s creators often refer to its individual segments as “Parts,” rather than the traditional “episode” nomenclature used for self-contained installments of (even serial) TV shows. While some critics have rolled their eyes at this terminological flourish, it is nonetheless based in something concrete. Mark Frost, co-writer of TP:TR (and co-creator of TWIN PEAKS), has confirmed that no thought was given to episodic composition during the writing process: “we just wrote as much as we felt needed to be written. We didn’t even think about it in terms of episodes.”

Although TV critics like Emily St. James have argued that each Part of TP:TR “has a rough episodic structure that helps viewers distinguish one from the other,” one of the only details I’ve seen anyone provide in support of this sort of claim is the basic fact that many of the Parts close with a band performing at The Roadhouse, thus providing evidence of intentional episodic design. As Matt Zoller Seitz writes: “Every episode runs an hour. There's usually a musical number at the end. The thing is very structured. As a TV series.”

Granted, the fact that 11 of the 18 hour-or-so-long Parts end with a band performance at The Roadhouse does at least demonstrate that the choices about how to split TP:TR up into parts were not made exclusively by throwing darts at a dartboard. Yet it hardly undercuts the insistence by Duwayne Dunham and Mark Frost that virtually no thought was dedicated to episodic structure or episodic content in the writing and editing of TP:TR. In other words, all it shows is that TP:TR, despite having been created as a single continuous narrative, was cut into roughly equal hour-long parts to satisfy TV programming needs, with Roadhouse performances slapped at the end of some of the Parts.

(I should add one additional caveat to the above statement that “virtually no thought was dedicated to episodic structure” in the construction of TP:TR. While I do not think this at all undercuts the main point, I think it fair to note that there is at least some evidence suggesting that David Lynch, in line with his long-time obsession with numerology, arranged at least a handful of narrative events in TP:TR such that they fall in specific Part numbers. For example, in Part 3, Cooper finds himself in a strange structure, in a world with a vast purple ocean, where he is faced with two differently numbered electrical outlets: “3” and “15,” matching his Great Northern room number 315. In Part 3 we see him enter the “3” outlet and become Dougie. Later, in Part 15, we see him start the process of exiting his life as Dougie by sticking a fork in a household electrical outlet. It is possible, if not most likely, that these numerical alignments are not coincidental. It is also possible that other examples exist: for example, the Log Lady’s declaration that “Laura is the One” falls in Part 10, a number that elsewhere in TP:TR Lynch’s character Gordon Cole highlights as the key “number of completion.” Yet these types of numerical alignments, to the extent they are intentional, can hardly be called typical of episodic TV series; instead, they are the product of a highly idiosyncratic artist.)

The Example of Part 8

Dunham points to the opening of Part 8 as something demonstrating TP:TR’s lack of concern with traditional TV-episodic form. “I think Part 8 does open with Cooper and Ray just driving along the road forever. A very, very, very slow opening and that’s not how traditional TV would ever open.... Nobody opens like that. You usually have an active opening and a super active ending, but that’s what I’m saying. They were never constructed to be anything other than a continuous narrative.” While I think Dunham overstates the matter (some TV series, like certain episodes of BETTER CALL SAUL, do in fact open that slowly), his general point about the odd structure of Part 8 is worth considering further.

In contrast to Dunham’s belief that the structure of Part 8 helps demonstrate why TP:TR is like a film, I’ve seen multiple instances online of people arguing that Part 8 exemplifies why TP:TR is structurally more like a traditional TV show. For example, Matt Zoller Seitz has written: “The power of ep eight of TP:TR comes from the filmmaking, but also from the break in continuity it represents from the rest of this great series.” And A.B. Allen, in the same viral thread quoted at the top of this post, writes: “This is so far beyond cringe inducing. THE RETURN doesn’t even behave like a movie. That widely acclaimed eighth hour is only as effective as it is *because* of how it sits within a season of TV. Ignoring that this is a series undermines the most interesting things about it.”

What I think these arguments overlook is that Part 8 *does not* merely consist of its widely acclaimed segment, the 40 minutes that begin with the Trinity nuclear test and end with the broadcast of the Woodsman’s dark poem. If it did only consist of those 40 minutes, then perhaps one could rightly argue, as Seitz and Allen seem to, that it shows how an episodic design at a constitutive level—often considered a hallmark of TV shows—is central to the delivery of TP:TR’s themes and story, with particular episodes dedicated to particular themes and story arcs, and intended to contrast and complement other episodes in specific ways. To the contrary, though, Part 8 begins with a full 10 minutes of other material that pick up the main storyline right where Part 7 left off, with Mr. C (Cooper’s doppelganger) fresh out of prison and driving with Ray along the highway; a musical performance by NIN acts as a palate cleanser of sorts before the final 40-minute segment commences. While one can draw a very loose connection between those first 10 minutes and the final 40 minutes—BOB and the Woodsmen make appearances in both, and both are generally dark in tone (although the Senorita Dido segment of the final 40 minutes is beautiful and hopeful)—there is no strong connection between the two segments in either theme or story, and presumably one could draw similarly loose connections between the final 40 minutes and almost any other 10 minutes of TP:TR’s narrative that might have been placed at the beginning instead.

The “break in continuity” those acclaimed 40 minutes represent, then, is not one between consciously-constructed TV episodes, but one between components of TP:TR’s long narrative. And such breaks in narrative continuity are not uncommon in films—e.g., think of the breaks in MULHOLLAND DRIVE, BARBARIAN, PSYCHO, FIRE WALK WITH ME... others can surely come up with even better examples. Part 8 may stand out because it contains that bravura segment, but nothing about the design or placement of the segment indicates that episodic structure, per se, is critical to the way TP:TR’s narrative plays out. If anything, it shows the opposite: that episodic structure is mostly *unimportant* to TP:TR.

Like Dunham, Sabrina Sutherland, the Executive Producer of TP:TR, has emphasized how radically different the process for making TP:TR was from the process for making the two seasons that aired in 1990-91. “[It] was run completely differently from the original. There was only one director. We shot this like a giant film. We shot everything before we edited everything before we mixed everything before we color-timed everything. It was a completely different process and completely different feeling. This was not TV in the usual sense.” While she has acknowledged that some of these production aspects have been becoming more popular in TV production (“I guess in this day, cross-boarding (where multiple episodes are shot at once) and having one director for multiple episodes is not unusual”), she notes that the degree to which TP:TR used these aspects is somewhat unusual (“We just took it a step further and had all 18 hours cross-boarded”), and that it starkly contrasts with the more traditional TV-production approach that was ubiquitous when the two seasons in 1990-91 aired (“This is something quite contrary to television from years ago”).

Filming Every Page of a Novel

While Dunham and Sutherland’s remarks focus on the aspects of TP:TR that make it more like a film than a TV show as traditionally understood, David Lynch and Mark Frost, the two co-creators of TWIN PEAKS, have expressed views that seem to focus more on the blurring of traditional categories represented by TP:TR. Frost, who originally made his name working as a writer and story editor on several seasons of the acclaimed 80s TV drama HILL STREET BLUES, has expressed that he “[doesn’t] necessarily think this is a TV show or a movie.” Instead, given its lack of episodic structure, on the one hand (making it unlike a TV show), as well as its extreme length, on the other (making it unlike a film), he compares it to “filming every page of a novel”—an art form in which he also is well-versed, having written several novels. (He adds that novels “have the the luxury of beginning more slowly... It is not, ‘You have to grad the audience by the throat in the first 35 seconds or you’ve lost them.’”) While the comparison to a novel may strike TV critics as another well-worn cliché used by TV showrunners in discussing the storytelling ambitions of their show, the types of TP:TR’s departures from traditional-TV enumerated by Frost, Dunham, and Sutherland suggest that Frost’s embrace of the “filmed-novel” moniker is actually built upon a more substantive grounding.

Notwithstanding his practice of calling TP:TR "an 18-hour movie," Lynch, for his part, has expressed that the distinctions are somewhat meaningless to him. "Television and cinema to me are exactly the same thing," Lynch has said. "Telling a story with motion, pictures and sound. It ended up being 18 hours." The creative processes, to him, are very similar. "It’s the same thing. You get ideas and you try to stay true to the idea as you translate it to cinema, and back then I saw the pilot as a film and now it’s the same thing. It’s a film. It’s just shown in parts." Contrary to characterizations of him as an anti-TV snob, then, he’s he's not elevating "film" over "television" in these quotes; he's just equating them. In fact, if anything, his quotes in recent years have elevated TV over film: "Television is way more interesting than cinema now. It seems like the art-house has gone to cable." (While he has expressed a preference for theatrical release over home viewing, it is clear that this stems merely from his fixation on the importance of high, immersive sound and picture quality to a viewers’ experience.)

TV, The Medium

These Lynch quotes on TV versus film are illustrative of a phenomenon that has plagued these types of discussions: they elide the differences between TV, as a medium, and TV shows, as an art form. That not everything that airs on TV is a “TV show,” nobody seems to dispute; people seem to have little problem acknowledging (in most cases, at least) that movies do not become “TV shows” simply because their first (or primary) release occurs on television or streaming services. Yet aside from these clear-cut instances of films on TV, there is a tendency for almost everything else that airs on television to be lumped together into an amorphous pile and labeled as a “TV show.” Looking at the “best TV show” lists compiled by major outlets from the past several years, one finds works structured in all manner of forms; from the standalone-anthology-installments of BLACK MIRROR, to the small-sketch-based KEY & PEELE, to talk and variety shows like THE DAILY SHOW, to the short and uniformly-produced FLEABAG (whose seasons, as a whole, have shorter running times than many of the films on the Sight and Sound list), to mostly non-serialized episodic shows like THE SIMPSONS, to the now more-ubiquitous serialized episodic shows like BETTER CALL SAUL.

What do all of these works have in common, apart from airing in segments on television or streaming services? Very little. The mere fact that a work has been cut up into smaller units—absent anything further—does not seem as if it should be significant in itself for purposes of classifying its artistic form. Indeed, anything can be cut up into pieces (as is often pointed out, many classic novels were originally released serially). The important question in this regard is seemingly whether a segmented structure is important to a work’s goals, to its design, to its identity; and if so, then how so. Yet even among TV critics, the fact of works’ original release in the medium of TV is often held to be more salient for purposes of comparative analysis than the formal artistic (sub)genres of those works airing on TV, of which there are seemingly multiple widely divergent ones, as seen above.

Indeed, the term “TV show” itself does not seem to reflect a coherent formal artistic genre, but rather merely to be an expression of a work’s existence in the medium of TV. Part of the conflict over TP:TR’s categorization seems to stem from Sight and Sound (and possibly other film-world lists, like those of Cahiers du Cinéma) making rankings apparently based on formal artistic genre, whereas many of the TV critics’ big-tent rankings seem to be based more just on the medium of TV. There are valid reasons for taking either approach, but we should be clear that comparisons of the two are not apples-to-apples, criteria-wise.

Unitary Authorship, or Auteurism

Apart from the issue of segmentation, and how a work utilizes it in both its structure and its production processes, one of the other main factors people seem to sometimes employ in assessing how a work like TP:TR should be categorized is the extent to which it has unitary authorship, or what we might call its degree of auteurism. The works on the Sight and Sound list of the “greatest films” all (as far as I know) are directed & written, in their entirety, by a single person or set of people, something that distinguishes them from TV shows where each individual installment is typically written and directed by different people than the next installment. (I realize that “auteurism” is typically used in film writing to refer specifically to the work of directors, but given the elevated status often accorded writers over directors in the world of TV shows, I use the term here to jointly refer to director(s) and writer(s) on a work, and acknowledge the problematic aspects of assigning sole authorship to one or two people out of the dozens or hundreds of artists & craftspeople who contribute on any given motion picture.) Here, unlike the two seasons that aired in 1990-91 (and the majority of TV shows), TP:TR is more like the films on the Sight and Sound list, insofar as it is entirely directed by Lynch and entirely jointly written by Lynch & Frost.

Comparing TP:TR to something like THE SOPRANOS, one of the consensus greatest TV shows of all time, is perhaps instructive. TP:TR differs from THE SOPRANOS on three of the major fronts we’ve been discussing: (a) unlike THE SOPRANOS, episodic form is of little importance to TP:TR’s structure; (b) likewise, its production processes were focused on one single entity, the work as a whole, rather than being segmented into individual productions for each episode; and (c) it was entirely directed by the same person, and jointly written by the same two people. Even so, TP:TR is similar to THE SOPRANOS on two major fronts: it is much longer (at ~16.5 hours) than a typical film, and its narrative builds on earlier seasons of a TV show.

Are these two factors—length, and what might be termed narrative contingency, i.e., a story that builds on top of prior installments—sufficient to make it inappropriate to consider TP:TR a film?

Narrative Contingency

Addressing the issue of narrative contingency first: it’s not uncommon for works widely considered films to have some degree of narrative contingency as well. Sequels exist, for one thing; to use an obvious example, THE GODFATHER PART II, #104 in the Sight and Sound ranking, has a story every bit as contingent on previous work as TP:TR. To be fair, the Sight and Sound rankings have, over time, differed in how they have treated sequel films. Starting in 2012, a rule change was implemented that prevented ballots from counting the Godfather film series as a single choice, with an explanation provided that this was being done “since they were made as two separate films.” Note that even prior to 2012, though, the Sight and Sound lists did not reject the Godfather works as “film”; rather, they merely considered them to be one single film, rather than multiple ones, notwithstanding their segmented nature. (However, the choice to consider only parts I and II, specifically excluding the third installment, as a single film ranking #4 on the 2002 list, seems dubious.)

Even some non-sequel films, such as adaptations, those based in true stories, and heavily allusive works, often build upon a preexisting knowledge base expected to be shared by viewers; and every work, to some extent, is created against an assumed backdrop of viewers’ knowledge of society, and of other works in the same genre. Most relevantly for the purposes of classifying TP:TR, consider the film TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME: it is this work, not the two TV seasons from 1990-91, that acts as the immediate predecessor in release to TP:TR. Notwithstanding FWWM’s relative narrative contingency on those two TV seasons (even though it is mostly a prequel, it is generally recommended to watch those two TV seasons first, given that its story draws significant resonance from its relation to those other works), it is not considered very controversial to call FWWM a film, and its #211 ranking on the Sight and Sound list has drawn little objection on that front.

Media organizations engaging in critical TV show rankings have taken conflicting approaches to classifying TP:TR’s relation to the TWIN PEAKS works from the 90s. For example, the 2021 BBC Culture ranking of “the greatest TV series of the 21 Century,” based upon a poll of 206 “TV experts - critics, journalists, academics, and industry figures,” limited its list to series that began in or after the year 2000. As such, THE SOPRANOS, whose first series premiered in 1999, was excluded from the list, despite the bulk of its episodes airing in or after 2000. Curiously, however, TP:TR was allowed on the list, and ranked #13; presumably, if one views TP:TR as the third season of a single TV show rather than a standalone entity, then it should have been disqualified from the list, like THE SOPRANOS.

(By similar logic, one can argue that TP:TR should not have been permitted in the “Limited Series” categories at the 2018 Emmy Awards, as the Emmys defines a Limited Series as a “complete, non-recurring story.” It mattered little, though, as—in slates that typify the ungainly mess that is TV categorization—Lynch’s work on the entirety of TP:TR lost the Limited Series or Movie directing Emmy to Ryan Murphy’s work on a single episode of THE ASSASSINATION OF GIANNI VERSACE: AMERICAN CRIME STORY, and Lynch and Frost’s work on the entirety of TP:TR lost the Limited Series or Movie writing Emmy to Charlie Brooker and William Bridges’ work on USS CALLISTER, a 76-minute episode of BLACK MIRROR that was classified at the Emmys as a TV Movie. Meanwhile, TP:TR failed to even get a nomination in the overall Outstanding Limited Series category for which it was submitted, being edged by GENIUS: PICASSO, GODLESS, THE ALIENIST, PATRICK MELROSE, and the winner, Murphy’s ...VERSACE....)

Like the BBC Culture ranking, the Dec. 2019 Rolling Stone list of the “50 Best TV Shows of the 2010s” treated TP:TR as a standalone work, ranking it #14; again, if it had been considered the third season of a TV series, it should have been excluded from the list, this time due to the list’s stated rules that, to qualify, the “majority of [a show’s] episodes had to have aired in this decade.” By contrast, the 2022 Rolling Stone list of the “100 Greatest TV Shows of All Time” grouped TP:TR in with the 1990-91 seasons of TWIN PEAKS and considered them a single, three-season show, ranking it #16. FWWM was excluded from this grouping, a choice that also shows the disorderliness of these types of TV-based categorizations, given the fact that FWWM is at least as connected to the narrative of the 1990-91 seasons of TWIN PEAKS as TP:TR is (and arguably more so, given that its production followed sequentially the year after the second season completed).

Does Size Matter?

As to the issue of length, it’s worth noting the diversity of “film”-sizes that have appeared in the Sight and Sound rankings: not only other longer works, like OUT 1 (720 minutes, #169 in 2022) and BERLIN ALEXANDERPLATZ (894 minutes, #202 in 2012), but also short films like MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (14 minutes, #16 in 2022) and UN CHIEN ANDALOU (21 minutes, #169 in 2022). TP:TR thus fits squarely within the broad, length-insensitive definition of “film” reflected in the Sight and Sound list.

It is fair to note the ways in which a 1000 minute film offers much greater chances for character, thematic, and story development than a 100 minute film, and the ways that a 1000 minute running time also presents different challenges as to how the work might be cohesively structured than a 100 minute running time. Similarly, though, one might equally note the myriad ways in which a 10 minute film presents very different opportunities for (and challenges to) structure and development than a 100 minute film.

Yet the appearance of the 14 minute MESHES... at #16 on the Sight and Sound list has kicked up nowhere near the fuss of the appearance of the nearly 1000 minute TP:TR at #152. One does not see viral Twitter threads painting those who included MESHES... on their Sight and Sound ballots as “people so embarrassed to adore [short films] they have to rewrite definitions to accommodate their own insecurity.” While one might argue that the comparison is inapposite, since “short films” are by their very name “films,” this seems mere verbal contrivance; the substantive issues remain.

Nor do I think it persuasive to argue, as many have, that the thing that separates TP:TR from true “films” (yet would not similarly distinguish short films) is that one cannot watch it in one sitting. First of all, as a mere technical matter, this is not true. While watching literally in one unbroken viewing is challenging (albeit doable), this is usually not the standard we hold and film or even TV shows to, given that bathroom breaks and the like are common for anything. And, at any rate, a number of fans have discussed their marathon single-day viewing sessions of TP:TR, encouraged by things like Showtime’s occasional marathon airings of the entirety of TP:TR on one of their channels. More importantly, “number of viewing sessions required to finish” seems like a pointless way to define a formal artistic genre, and one that rings particularly hollow given the rising prevalence of film lovers streaming movies at home in segments over the course of two or more days. (For example, after its 2019 release on Netflix many people online discussed watching THE IRISHMAN’s 3.5 hour running time over three or more viewing sessions, a breakdown that at least superficially matches MoMA’s theatrical airing of the entirety of TP:TR over the course of three segments on Fri/Sat/Sun in 2018.) Speaking from my own personal experience, the majority of films I've watched in the last three years have been at home, viewed in multiple sessions over the span of two or more days.

A TV Long-Form Film

Notwithstanding the above considerations, I do think it is fair to say, per Mark Frost’s quotes about TP:TR’s novelistic qualities, that the length of a work affects its artistic possibilities, a point reflected in the literary distinction between novels, short stories, and novellas. It therefore seems reasonable to question the appropriateness of classifying filmed works of drastically different lengths in the same formal artistic (sub)genre. Even if one declares TP:TR to be something other than a traditional feature film, though, the upshot is not that TP:TR should be considered a serialized TV show like THE SOPRANOS. After all, the major distinctions between the two works, as discussed earlier, still remain. Rather, it would seem more appropriate to create a new moniker – long-form film, perhaps, as opposed to feature films and short films. Given their length, these long-form films will usually air first, or only, on TV or streaming; this does not thereby convert them into a serialized TV show, but it does make it fair to call them a type of TV film (referencing their use of the medium of TV). Moreover, I think a recognition of the qualities that make it natural to think of long-form films as a formal artistic subgenre of films themselves might yield a surprising conclusion: it would actually be demeaning to and snobbish towards the medium of television for prestigious lists like Sight and Sound to NOT recognize works like TP:TR as films, merely because they air on TV.

Long-form films could possibly be defined as follows: (a) unitary authorship, i.e., their being wholly written and directed at each and every step by the same person or small set of people; (b) a non-episodic narrative (thus something like DEKALOG, with its sharply episodic, anthology-like narrative, would not qualify), where being broken into installments for the purposes of airing is not disqualifying in and of itself; and (c) a length substantially longer than a typical feature-length film – to pick a specific limit, let’s say at least 4.5 hours long, which would exclude most of the longest theatrically released feature-length films (like A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY, at 3 hours 57m). Some may wish to loosen these criteria; it’s worth noting that of the three works Emily St. James highlighted in 2017 as having similar degrees of auteurism to TP:TR (BETTER THINGS, THE YOUNG POPE, and TOP OF THE LAKE: CHINA GIRL), none of them meet these three criteria as stated. A more fulsome attempt to analyze the growing film-like aspects of long works airing on TV and streaming would need to grapple with these examples, as well as numerous others, such as CARLOS, TOO OLD TO DIE YOUNG, RIGET, and THE KNICK.

As boundaries continue to blur, hopefully film awards and rankings like the Oscars will, following the lead of the Sight and Sound list, open eligibility to long-form films, perhaps in their own category. As is, the Oscars limits many awards to films released in the medium of theatrical screenings, but it permits short films to qualify by screening at a “recognized” film festival, a type of hoop-jumping that feels needlessly arbitrary in a world where anyone can watch almost anything, at any time, at home.

There is no way to get rid of the inherent messiness of any attempts at categorization. (For example, some movies display elements of episodic structure: PULP FICTION, for example. Curiously, PULP FICTION is the same length as FLEABAG Series 2; both are broken up episodically; and both have unitary authorship. The prime formal differences are just that FLEABAG aired on TV, and has some narrative contingency on a previous series. Basically, though, there is a strong case for them belonging in the same formal artistic genre.) Lines will inevitably be blurred, works will inevitably straddle categories. And that’s fine. There needn’t be a binary between individual categories—it should be fair to use multiple categorical terms to apply to a single work, to the extent it exhibits such varying characteristics.

And at least one of the categories that should apply to TP:TR is that of a film. A long-form film, airing on TV.

POSTSCRIPT: I'd like to add a note of regret concerning a tossed-off tweet of mine on this topic, which you can see below, that received a moderate amount of attention on Twitter. (1) It uses a broad brush to seemingly paint as whiny all TV critics who objected to TP:TR's classification as a film, which is neither kind nor accurate; in fact, a number of critics, including some quoted in this piece, set forth thoughtful and principled analyses which carefully considered the reasons and ambiguities of the situation. (2) It also flippantly uses a broad brush in critiquing the reception of TP:TR by TV critics, when in fact it was broadly praised and championed by numerous TV critics, including those quoted in this piece. While I do take issue with the ways some critics addressed TP:TR, I regret making such unfair, broad generalizations.

#twin peaks#sight and sound#david lynch#mark frost#twin peaks: the return#tv criticism#film criticism#long-form film

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The anti-fat sentiment in "Body of Proof" is significant and so far not examined.... there are probably about a million other unexamined bias / stereotypes in it too that either I am either not equipped to fully appreciate/articulate or missing as I watch.

That said...the show does some things extremely well.

It's interesting watching older procedural series that only went like 3 seasons... They are like stepping stones of popular culture.

I like finishing them and then going out and reading fan and critical responses - both current and of the time.

I also like looking at how the series do or don't advance characters - particularly the stories of supporting cast. "Lie to Me" struggled with that and I am trying to figure out the various factors that led to that element of the storytelling. I think I need to research a bit more about "Show bibles" and the role of story editors and other folk in writers rooms wrt continuity. I have done some investigation over the years but I have more and more questions as I continue to engage with popular media through fanfiction and tumblr.

One of my fav series was Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip... But it only lasted a season. It was created by the same folks who did West Wing (which I LOVED growing up and have always felt did a very consistent job of developing a large cast of characters...although I maybe should rewatch through my current lens).

#body of proof#lie to me#character development in series#tv appreciation#tv criticism#west wing#studio 60 on the sunset strip

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"HOLY SHIT, 9/11 WAS 20 YEARS AGO??" SAYS MAN WHO WITNESSED THE EVENTS FIRSTHAND

#dirty laundry#dropout.tv#dropout tv#dropout#critical role#critrole#cr#sam riegel#aabria iyengar#anjali bhimani#liam o'brien#aspen tag#aspen snapshots

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

listen like. people are totally entitled to their opinions and criticisms of the pjo show but. sometimes it’s just hard to hear/read. I know the show isn’t perfect but seeing the cast & producers talk about it and seeing the level of love and excitement theyve put into the work, idk, I feel for them having people tear it to shreds. criticising the author himself for not adapting it well when he’s doing something different with a new medium, saying they’re sorry for the kids who love the books but have to act in this “terrible” show as if these kids aren’t THRILLED by the opportunity and just so committed to giving the show their best.

(watch the behind the scenes documentary. seriously.)

again totally valid criticisms & opinions!! but you win some and lose some in an adaptation. eg. trying to expand on themes, keep a consistent tone, appeal to a broader audience (including those of us who loved the books as kids but are now!!! adults!!!), keep within budget, etc etc all these things involve some trade offs. sure some of the humour and goofiness has been lost but we also get amazing beautifully acted scenes that really expand on core themes of family or who is a monster etc etc.

speaking on a personal level I have had a hard time these past few months and this show became a genuine escape, a way for me to connect with my sister watching the episodes together, a rediscovery of my inner 12 year old who waited so long for this. and I know there are people who are like me and they had certain expectations and that’s why they’re disappointed and that’s so valid, but it’s a lot of negativity sometimes, & I just wish we could give a little grace bc making a creative thing is hard, and pleasing everyone with that creative thing is impossible, and most of all, maybe we could revel a little bit more in this unique complex piece of work that lots of people poured their hearts into with nothing but the best of intentions.

#again u are entitled to your opinions maybe this is just#my very long way of saying please tag your criticisms#I’ve filtered the tags but it still pops up on my feed#percy jackson#percy jackon and the olympians#pjo tv show#pjo series#pjo#pjo fandom

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Morning Show episode 3.10 "The Overview Effect"

The season of Alex Levy! It’s been awhile since I really felt proud of a character the way I feel proud of her. It’s also not too often in shows that you get to see a character grow and actually implement that growth. Typically, a character ‘learning their lesson’ marks the end of the story, but The Morning Show has a really unique pacing that does wonders for character development. They all contain multitudes and nuance and flaws and strengths, and that complexity of every individual is the exact thing that fuels the chaos behind this show.

I also think this show is slept on for some reason? I never hear anyone talk about it which confuses me with this kind of cast. From what I gather, it does too good a job capturing all the problems in our society and that’s a downer. I’ve always been impressed by that quality about it, the whole thing would feel silly if it didn’t feel authentic. But for anyone who feels that The Morning Show is just a stressful and sad reminder of the state of US capitalism and media- this season surprised me by building to an incredibly hopeful and empowering conclusion. One all about growth and accountability. I honestly feel like I have a better understanding of what the phrase “doing the work” actually looks like in the context of social justice and power after watching this.

Jennifer Aniston in "The Overview Effect". Image courtesy of The Hollywood Reporter.

Before this season’s finale, my opinion was leaning the complete other way. Bradley, who I’ve always identified with and loved, covered up her brother’s involvement January 6th. Hal wasn’t just there; he attacked a cop- and people were looking for him. Bradley didn’t just discretely ignore it, she doctored him out of footage, lied to the FBI, and continued reporting on the event. To me, she lost all her ethical standing with this, and she continued doing the news for a long time before anyone found out. As Laura Peterson told her, “It’s obscene”.

But then again, Laura only found out about it by scouring all of Bradley’s leaked emails and texts in search of evidence of Bradley sleeping with Cory. Before Alex got involved during “The Overview Effect”, I was rolling my eyes at the both of them. It was screaming ‘liberals who can’t get off their high horse but also aren’t ethical in their own lives when it really comes down to it’. Laura being so insecure about Bradley sleeping with someone when they weren’t even together to the point that she would violate her privacy like that felt incredibly low for Laura. Almost out of character. Her finding out about the Hal situation and her subsequent breakup with Bradley is what catalyzed the climax of this season, but I really wish she had found out some other way.

Nonetheless, I saw a glimmer of hope for Bradley when she resigned on-air. It was dramatic, as she and Alex both often are, but it was a step towards accountability. Losing her girlfriend, her job, and potentially the rest of her career made me feel like she is, indeed, paying the price for her choices.

Something else also happens here that manages to put Bradley’s transgressions in perspective. Paul Marks stops by Bradley’s green room right before what would be her final broadcast, blackmailing her with his knowledge of how the January 6th cover up could blowback on Laura, and telling Bradley to stop digging into Hyperion. “The Overview Effect” opens with Paul blatantly (to us) lying to Alex about that conversation, telling her instead about the support he offered Bradley in that moment.

Paul Marks was a great character addition this season. They planted the seed well that he was ‘not what he seemed’ and had something going on with Hyperion, his independent space company that was working with NASA. Stella had an old friend who tried to blow the whistle, but Stella really straddles the line between empowering from the top down, as she claims to do, and simply playing the game. She scared the friend away, and so enlisted Bradley and Chip to help her get to the bottom of whatever it was that she now regretted ignoring. All we knew for most of this season was that he didn’t assault anyone- he was “too smart” for that- but he sure did something, and absolutely no one would come forward.

Jon Hamm and Jennifer Aniston in "The Overview Effect". Image courtesy of TV Line.

The chemistry between Jon Hamm and Jennifer Aniston is really the thing that made him- and her- compelling. It was so genuine, and his affection for Alex is the one thing about him that I do still believe to be true. I’ll say it, he had great charisma and calming DILF energy. Without knowing what exactly he had done, the smitten part of me wanted to believe that it was nothing. Seeing that side of him, understanding what Alex saw in him, makes what she does in this episode all the more impressive.

Ever since her live resignation, Alex has been texting and calling Bradley to no avail. After her conversation with Paul, the one where he lies through his teeth, Alex decides to go check on her. When she shows up at her apartment, Bradley looks unhinged. Disheveled and manic, Bradley tells Alex she can come in if she leaves her purse and phone in the hall. Alex obliges, and when Bradley gets talking, it all makes horrifying sense.

Bradley admits to everything about January 6th, but then says something else- Paul knew about it too, and in their conversation, he referenced things he could only know if he had been listening to her fight with Laura. Alex is shocked, but, to her immense credit, not disbelieving. Bradley says she’s going home to West Virginia for awhile to take care of things with her family. Alex leaves, wrapping her head around the possibility that Paul is surveilling Bradley- and who knows who else. On the way home, she texts Bradley that getting away for a bit is a good idea, and that she should go back to West Virginia. After a moment of thought, she changes West Virginia to Hanover, a place they didn’t discuss, and hits send.

Reese Witherspoon and Jennifer Aniston in "The Overview Effect". Image courtesy of IMDb.

Alex’s little experiment proves fruitful. She gets back to her apartment and tells Paul that she went to visit Bradley. They chat about it, Paul playing a supportive boyfriend. So supportive that he wraps Alex in a hug and says Alex is right, Bradley should get away for a bit, go back to Hanover and recoup. Alex freezes. She doesn’t give herself away though. She agrees, hugs him back, and spends the night sharing a bed with someone that we and she now all know is very scary.

Then she pays a visit to Laura. A plan is formed, but we don’t find out about until the Hyperion-UBA deal is minutes away from going through. Right about as people are ready to start pouring champagne, Alex says there’s just enough time to put a counteroffer on the table. Laura has worked some magic at her network, NBN, and she and Alex are proposing a merger. They will share resources to save costs and form a true journalistic partnership.

Paul is caught completely off guard. He asks to speak to Alex in private, where they round a corner to come face to face with Stella and Kate- the original Hyperion whistleblower. They give Paul an ultimatum- walk away from the deal and come clean to NASA about sending them falsified reports on his rockets- or they will report on everything. Oh also- the transmission break when Bradley and Cory went to space? Not a broadcast issue, Paul cut the feed because the ship’s navigation system malfunctioned. Alex was absolutely right not to get on that thing. Also did this plot line remind anyone else of a certain submersible?

Paul, of course, accepts these terms because the alternative is life-ending, but he’s still flabbergasted at Alex’s turning on him. It’s a little sad, he really did love her and didn’t see it coming whatsoever, but not that sad because he was doing some fucked up shit.

For all of Cory’s heart attack-inducing running around this season, it was Alex single-handedly saving UBA multiple times over. She brought Paul Marks to the table, and she kicked him back away from it. And none of it was selfish. She was so thoughtful this season it blows me away. While Paul and Cory were both leaking scandals like chess pieces, Alex was processing them all with poise.

Billy Crudup in "The Overview Effect". Image courtesy of IMDb.

The idea that all the things that consume a news cycle, that prompt a notes app apology on Instagram and cost people their careers, are, at their source, a meaningless power play by executives with zero genuine interest, is the saddest thought posed this season. It was demoralizing to see Cory drop a bombshell and pretend to care about it when really all it meant to him was a successful board meeting. Knowing that origin of all these scandals, watching Alex, Chris, Mia, and Yanko put so much heart into thinking through these issues of race and pay inequality is just sad in some ways. The people at the top were preying on these ethics, on the outrage, on the news cycles, and people’s careful attempts to do the right thing were the very things executing Cory’s delicately laid plans.

Cory’s last-ditch attempt to reconcile with Cybil to save UBA really cements that all these issues of inequity meant nothing to him. He’ll go whichever way the wind blows. Alex, meanwhile, rejected Cybil’s pleas for allyship and engaged with her just enough to hold her accountable (“It isn’t just an email. You paid a black person less than a white person for the same job.”) She also knew when to take action and when to step back. She interviewed Paul on her own show and I truly don’t think their relationship ever clouded her work, but when Cybil was going to be interviewed, she was the one who arranged for it to be Chris doing the interviewing.

And in the end, Alex didn’t let a trail of injustices cloud her perspective. She was able to put what Bradley had done on the backburner for a moment, and get Laura to do the same, to tackle the wrongdoing of all wrongdoings. She did what Paul was relying on our society not being able to do- seeing through a scandal to its source. And she didn’t do it to save her own job- she was about to get the rebrand of a lifetime- she did it simply because it was the right thing to do.

But she didn’t forget about everything else. Before the credits rolled, Alex was holding Bradley’s hand as she and Hal stood outside an FBI office. Alex tells her it’s going to be okay, that she’ll be there for her, but that she has to do this. Bradley knows she does. This is what friendship should look like. Both unconditional support and accountability. I love this example proving that you don’t have to sacrifice one for the other. That someone can have room for growth, and they can do it by your side, with your support. That’s how we all get better.

Reese Witherspoon and Jennifer Aniston in "The Overview Effect". Image courtesy of IMDb.

I’m just so thrilled to see The Morning Show go this way. If you know me, you know I love a happy ending, and this may not be that, but it is hopeful, empowering, and motivating. And that’s what it’s all about, I think.

#the morning show#jennifer aniston#alex levy#reese witherspoon#bradley jackson#jon hamm#paul marks#billy crudup#cory ellison#tv#tv review#tv criticism#laura peterson#julianna margulies

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

I finished season 9 of Shameless this morning. When I get to the end I will debrief, as a reward for watching 134 episodes of anything in the modern era.

#text post#tv analysis#tv criticism#criticism is love#I would never critique something that didn't engage me

0 notes

Text

Pros of this Episode:

Annabeth ripping into Procrustes every time he speaks by threatening to cut off his head. She is Done TM and I am so proud of her

Percy being a New Yorker once again, lying through his teeth, and calling them suckers. Also RIP to “it was a big bathtub” but “I mean…we’re all dying…to some extent” SLAPS

Grover and Percy looking at each other after finding the Master Bolt like “oh shit oh fuck oh shit oh fuck” I felt that

Hades and his Fruity Little Vibe, being so flamboyant and over-the-top but also still nice in his own way, You go Glen Coco

Sally. Everything with Her, Sally and Percy, Sally and Poseidon, Sally and the bitchass principal, Sally. Sally Jackson. End of story.

Cons of this Episode:

So I’m not a fan of- *gunshot, I am killed instantly*

#the scream I scrumpt when Annabeth yelled at Crusty from the back room#also Cerberus’ character design was adorable#you’re not getting my criticism after I posted about last episode#I’m not opening Pandora’s box thanks#percy jackson#pjo#percy jackon and the olympians#pjo tv show#percy jackson and the olympians#percy jackson tv show#pjo spoilers#percy jackson the lightning thief#pjo series#grover underwood#annabeth chase#sally jackson#hades pjo#hades#Poseidon#poseidon pjo#procrustes

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok, I know we are all excited about the news and all but i feel like i need to give this as a PSA:

Don't be fucking weird.

As a nosy bitch myself, i empathize with the curiosity. I mean, we all wanna know all the deets and all the gossip and such, and I know we have all been waiting for this moment since that Game Changer episode, but, as a reminder, NO INFORMATION ABOUT BRENNAN AND IZZY'S CHILD IS ANY OF Y'ALL'S BUSSINESS.