#Rusyn

Text

Lemko woman, Ukraine, by Ксенія Малюкова

#lemko#rusyn#ukraine#europe#eastern europe#folk clothing#traditional clothing#traditional fashion#cultural clothing

388 notes

·

View notes

Text

The word “Slavs” in the Slavic languages

Old Church Slavonic: Словѣне (Slověne)

Ukrainian: Слов’яни (Slovjany)

Slovak: Slovania

Czech: Slované

Polish: Słowianie

Kashubian: Słowiónie

Silesian, Lower Sorbian: Słowjany

Upper Sorbian: Słowjenjo

Slovene: Slovani

Serbian, Macedonian: Словени (Sloveni)

Montenegrin: Словјени (Slovjeni)

In these languages the pronunciation of the root has shifted from /o/ to /a/:

Russian, Belarusian, Rusyn: Славяне (Slavjane)

Bulgarian: Славяни (Slavjani)

Croatian, Bosnian: Slaveni

#slavs#slavic#ukrainian#slovak#czech#polish#kashubian#silesian#sorbian#slovene#serbian#macedonian#montenegrin#russian#belarusian#rusyn#bulgarian#croatian#bosnian

169 notes

·

View notes

Text

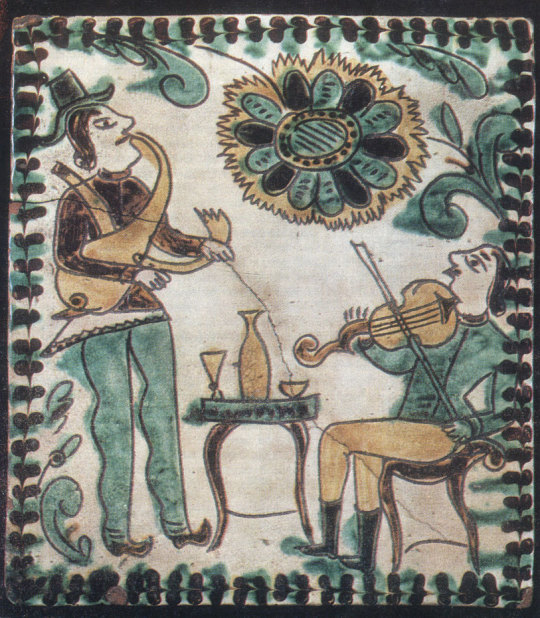

Jewish and Ruthenian musicians in Verecke, Ukraine (then Hungary, Bereg county), 1895

#folk music#jewish#ruthenian#rusyn#ukraine#hungary#klezmer#ruthenian music#ukrainian music#eastern carpathians#eastern europe#1890s#hutsul

603 notes

·

View notes

Text

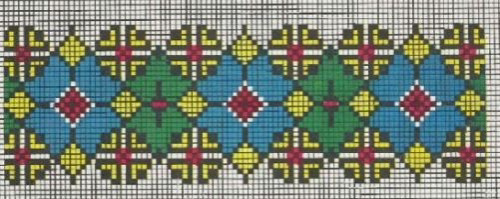

More older pieces.

The orange pattern is Rusyn and the blue/green is from Ukraine.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

“In Kosiv, death took Oleksa Bakhmatiuk, a Rusyn, a man of great talent and wide fame, whose obituary now appears in foreign magazines. He was a peasant, uneducated, a Kosiv Hutsul. As a self-taught potter, he made pots, jugs, and bowls that were works of art. Everyone was fascinated by his drawings with their gentle simplicity and naivety, fascinated by the execution, imagination, and color." - Lviv newspaper Dilo (1882).

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

Non-English songs that I listen to

To celebrate 4,000 followers (😯, thank you so much!!), I have decided to post a list of non-English songs that I listen to. Most of them are in my target languages, but I like some songs of which I don't understand a word 😅

Albanian

Lejla by Elvana Gjata ft. Capital T and 2PO2

Arabic

السيّدة النّصر/Doña Victoria by Raja Meziane

مية و خمسين (Miyye W Khamsin) by Nancy Ajram

يا حبيبي (Ya Habibi) by Mohamed Ramadan & Gims

Armenian

Յարխուշտա (Yarkhushta) by Sevak Amroyan

Catalan

30 dies sense cap accident by Els Amics de les Arts

Ara, aquí, present by Blaumut

Heroïnes de la fosca nit by el Diluvi

Història d’Espanya (explicada pels espanyols) by Brams

Huracà by Sense Sal amb Txarango

Jennifer by Els Catarres

Semblava que fossis tu by Els Amics de les Arts

Sóc d’un país by Brams

Telepàtic by Minova

Tornarem by Lax’n’busto

Un secret que t’havia de dir by Brams

Franco-Provençal

La Tita Eun Vacanse by Le Digourdì

French

Alien by Louane Emera

Alors on danse by Stromae

C’est la vie by Khaled

Chez nous by Patrick Fiori

Dès que le vent soufflera by Renaud

En chantant by Louane Emera

Je te déteste by Vianney

Je vais t’aimer by Louane Emera

Je veux by ZAZ

Je vole by Louane Emera

Jour 1 by Louane Emera

La Marseillaise (It’s the French hymn, but I love it 😂)

La vie est belle by Indochine

Maman by Louane Emera

Papaoutai by Stromae

Sur ma route by Black M

Tous les mêmes by Stromae

Tu vas me manquer by Maître Gims

Vois sur ton chemin by Les Choristes

Galician

Terra by Tanxugueiras

Gaulish

Epona by Eluveitie

German

99 Luftballons by NENA

194 Länder by Mark Forster

Atemlos durch die Nacht by Helene Fischer

Auf uns by Andreas Bourani

Copacabana by IZAL

Die Liebe lässt mich nicht by Silbermond

Drei Uhr Nachts by Mark Forster, LEA

Feuerwerk by Wincent Weiss

Geboren um zu leben by Unheilig

Ich lass für dich das Licht an by Revolverheld

Irgendwie, irgendwo, irgendwie by NENA

Ist da jemand by Adel Tawil

Je ne parle pas français by Namika

Legenden by Max Giesinger

Leichtes Gepack by Silbermond

Nur ein Herzschlag entfernt by Wincent Weiss

Nur für dich by Wise Guys

Sag mir was du willst by Clueso

Schon okay by JEREMIAS

Traum by CRO

Übermorgen by Mark Forster

Wer kann da denn schon nein sagen by Feuerherz

Wir sind frei by Berge

Greek

Όνειρό μου (Oniro mou) by Γιάννα Τερζή (Yianna Terzi)

Irish

D’Aon Ghuth Amháin by Seo Linn

Italian

Non mi avete fatto niente by Ermal Meta, Fabrizio Moro

Non è vero by The Kolors

Latin

City of the Dead by Eurielle

Mandarin

作勢裝腔 by 張韶涵 Angela Zhang

倒數 by 鄧紫棋 G.E.M.

天亮以前說再見 by 曲肖冰

我的歌聲裡 by 曲婉婷

是他不配 by 孫盛希 Shi Shi

淒美地 by 郭頂 Guo Ding

蓋亞 by 林憶蓮 Sandy Lam

裝醉 by 張惠妹 aMEI

諷刺的情書 by 田馥甄 Hebe Tien

陽光宅男 by 周杰倫 Jay Chou

Mongolian

Yuve Yuve Yu by The HU

Russian

Бадола by Альбина и Фати Царикаевы

Жить by DJ SMASH, Полина Гагарина & Егор Крид

Ищи не ищи by Ирина Круг

Когда рядом ты by Винтаж

Май by Клава Кока

На Титанике by Лолита

Не любовь by Ханна

Не пара by Потап и Настя

Небеса Европы by Александр Рыбак

Прованс by Ёлка

Прогулка by Земфира

Я свободен by Кипелов

Rusyn

Štefan by Hrdza

Slovene

Hvala, ne! by Lea Sirk

Spanish

20 de enero by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Abrázame by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Adiós by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Como un par de girasoles by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Cuéntame al oído by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Cuídate by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Deseos de cosas imposibles by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Dices by Selena Gomez

Dulce locura by La Oreja de Van Gogh

El 28 by La Oreja de Van Gogh

El mismo sol by Álvaro Soler

El universo sobre mí by Amaral

El último vals by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Él no soy yo by Blas Cantó

Geografía by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Hacia lo salvaje by Amaral

Inmortal by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Jueves by La Oreja de Van Gogh

La esperanza debida by La Oreja de Van Gogh

La playa by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Llévame muy lejos by Amaral

Marta, Guille, Sebas y los demás by Amaral

Más by Selena Gomez

Mon amour by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Moriría por vos by Amaral

París by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Pop by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Puedes contar conmigo by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Rosas by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Sirenas by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Soledad by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Te necesito by Amaral

Un año sin ver llover by Selena Gomez

Un mundo mejor by La Oreja de Van Gogh

Vestido azul by La Oreja de Van Gogh

#langblr#albanian#arabic#armenian#catalan#franco-provençal#french#german#greek#irish#italian#latin#mandarin#mongolian#russian#rusyn#slovene#spanish

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

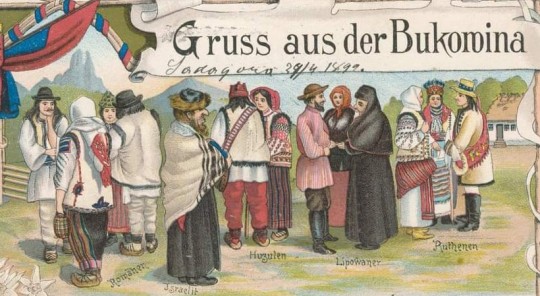

Different ethnic groups of the historical Bukovina region (today part of Ukraine and Romania) on a postcard from Austria: Romanians, a Jew, Hutsuls, Lipovans und Ruthenians.

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

being a rusyn and extremely proud of my tiny little beautiful minority heritage while not being pagan, eastern orthodox or greek cath. gives me such massive imposter syndrome vibes. i know modern rusyn leaders are sort of trying to divorce religion a little bit to attract the young people back but religion was and remains such a critical component of rusyn culture. and because i’m actively being Jewish im like well. can’t really say slava isusu chrystu so ahoj it is i guess. like did y’all have to make everything about the church or paganism omg 😔

also it’s not like there weren’t or aren’t jewish rusyns cause we lived together very closely and affairs did happen despite intermarriage being totally not allowed on all sides (how i became ashkenazi LMFAO) bc the rusyn boys liked the pretty jewish girls but it’s so uncommon there’s probably like three others in the world and i feel like some kind of weird fuxked up ethnoreligious show pony

#jumblr#rusyn#lemko#hutsul#boiko#dolinyan#rusznak#rusyny#RUSYNBLR#religion#ethnoreligion#identity crisis#very cool

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rusyn woman, Ukraine, by Serhij Mazur

#rusyn#ukraine#europe#eastern europe#folk clothing#traditional clothing#traditional fashion#cultural clothing

311 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rusyn woman from Kolomyya, Ivano-Frankivsk Region, 1880

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hutsul musicians in the Carpathian mountains

19 notes

·

View notes

Link

Over 100 minutes of recordings at the intersection of rural mountain music, new recording technology, Slavic immigration, and folk theater, collected with the assistance of the foremost authority on Rusyn recording in the U.S., Walter Maksimovich , this album will seem strange and foreign to many listeners but just imagine how strange and foreign life in the U.S. might have felt to the performers.

Lemkos are one of several ethnic minorities, collectively called Rusyns, who have been natives of the Carpathian mountains on both slopes the present-day Polish-Slovak border, the historical district of Galicia, for centuries. Tens of thousands of Rusyns arrived in the U.S in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, settling largely around the factories and mills of Pittsburgh (Andy Warhol’s family among them) and Cleveland with communities in Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Alberta, Canada. (Thomas Bell’s classic novel Out of This Furnace describes several generations of Lemkos around the steel mill in Braddock, Pennsylvania.) Like many other Slavs, they were often recruited through agents of the coal industry in collaboration with the steam ship companies to participate in the American labor force with the expectation that there would be a home to go back to. The wars in Europe prevented that.

While Canary’s bandcamp releases are primarily an outlet for my own research, some stories are inseparable from earlier, authoritative work. In this case, Walter Maksimovich and Bogdan Horbals’s beautifully detailed monograph Lemko Folk Music in America, 1928-30 (published by the authors in 2008) describes the details of the recordings of Lemko music in New York City in vividly. When I wrote to Maksimovich to ask permission to quote freely and use an image from it for this project, he not only accepted but also kindly offered to loan me exceptional copies of the original discs to use. With gratitude for his generosity, I’ll say that the vast majority of the story that follows is derived from his original research and writing.

Stefan (Steve) Shkimba (also Szkymba, Shkymba, or Skimba) was born Feb. 3, 1895, according to most of his surviving documents, or March 10, 1894, according to some family members, in Wołowiec, a small village 12 miles outside of Gorlice in present-day Poland just north of border with Slovakia. At age 18, he arrived carrying $60 at the port of New York on June 10, 1912 to join his older brother Jan (John, b. Jan. 8, 1887), who had arrived seven years earlier, in Brooklyn. He moved along with Jan and his wife Anna (b. 1891 in Volovets, present-day Ukraine) to Waterbury, Connecticut, where Jan had a job working on machine belts. Stefan worked odd jobs before enlisting for service in World War I from August 1917 to October 1918.

An estimate by Paul Robert Magosci in 1994 gives the number of Lemkos in the U.S. circa WWI as 55,000. Military service paved the way to legal citizenship for many immigrants, and Stefan Shkimba was naturalized in 1921. It may have also provided a degree of financial and social stability, allowing him to marry Mary Wislocka in New Jersey in 1918. The couple remained in Waterbury Connecticut, along with Jan Shkimba’s growing family, for about eight years. There Stefan preoccupied himself there in Lemko community activities, becoming a co-founder of the Carpatho-Russian National Club, an early branch of the Pennsylvania-based Lemko Committee.

Stefan and Mary relocated to Brooklyn in 1926, where he found steady work with the Transit System of the City of New York as a streetcar motorman, a job he kept for at least 15 years, while living at 96 Bedford Ave in Williamsburg. It was there that his devotion to ethnic organizing and his fascination with American technology culminated. Shkimba later described his situation (translated by Walter Maksimovich):

“…from the beginning of my arrival in America in 1912 right up to 1928 the idea was forming in my head that there will come a time when we Lemko-Rusyns, just like the other neighboring Slavic brothers, will be able to generate an artist that will take our beloved motherly words, lyrics, ethnic music, and place them on records. […] Seeing Polish, Slovak, and Ukrainian records being produced, I asked myself why not our own Lemko recordings? This was eating away at my insides, causing lack of sleep, and I asked myself when will one of us, a Lemko, release our own music on a record?”

His worrying was perhaps unique but entirely understandable. Eastern European immigrants to the U.S. accounted for about a third of the massive inward migration to the U.S. during the period 1880-1920, and when the record business began catering to them from 1910 onward, recordings in Polish, Ukrainian, and Slovak significantly outsold those by German-, Irish-, or Italian-born immigrants, who represented vastly larger per-capita populations. Although there was an eagerness to participate in the modern inscription-and-dissemination process of the record business, Shkimba’s sensitivity to a kind of exclusion may have been heightened as member of a struggling and geographically scattered minority that the broader American culture viewed as one lumpen proletariat of “polaks” and “hunkies,” relegated to hard labor and just enough housing, sausage, cabbage, and beer to keep them and their screaming children quiet, while in the homeland, attempts at an autonomous Lemko nation had come and gone.

In December 1925, the brilliant village-style Ukrainian violinist Pawlo Humeniuk (b. 1883) released a few records on the Okeh label before recording again in March 1926. The latter session included a recording that was basically a comedy sketch with musical interpolations that was issued as a 12” disc titled the “Ukrainian Wedding,” depicting all of the big emotions that you’d find at a typical Ukrainian wedding. (Touring theatrical groups during the 1910s and ’20 presented reenactments of weddings as entertainment and excuses to party for the immigrants.) For the equivalent of about $25 in today’s money, it offered about eight minutes of entertainment and was a runaway hit, selling well over 100,000 copies in a time when 500 copies was enough to satisfy the labels. From that moment forward, Slavic Americans had a voice, and it changed the record business in America for decades.

So, it was probably not coincidental that one day in early 1928, Stefan Shkimba decided to claim illness and leave work early from his job running a streetcar, when he crossed the bridge to Manhattan to beg his case to record the music of his own people, it was Okeh records, the second-tier label that had first recorded Humeniuk, that he approached. Their hesitant agreement was accompanied by a requirement of $50 - nearly a month’s worth of his wages - as a guarantee to cover costs in case the recording didn’t sell. Shkimba quickly assembled a group of three singer and two instrumentalists including the violinist Van’o Zapeka (who had published a book of Lemko tunes in 1920), all of whom were born in the old country between about 1877 and 1897, and brought them on April 4, 1928 to make a record titled “Lemko Wedding.”

The performers had not played together before, and it did not go well. The resulting disc was extremely raw and amateurish. Shkimba decided to released it anyway, but perhaps by virtue of his having been well-established in the Lemko cultural scene, and perhaps because of his need to make the project pay back on his investment, it sold incredibly well. Okeh let him continue the series of Lemko Wedding discs at five succeeding sessions from August 1, 1928 through February 27, 1929, and he took on the task with increased professionalism and some additional musicians. When the “Wedding” had run its course, he supplemented the formula with recordings of a “Lemko Engagement,” a description of life “At Mother-in-Law’s,” of domestic life, and a dance party in a tavern, through the end of 1929.

Advertisements he placed in the Lemko language press excoriated its readers that pride in them being Lemkos should require them to buy the records, and they were often willing to do so. Having sold about 100,000 discs from the series, many of them out of his own home, Shkimba then worked with Michael W. Duzey (b. Pielgrzymka Nov 22, 1893; d. New York March 24, 1949) on a now lost Lemko Wedding movie, made according to Maksimovich on a farm in Connecticut. (An unrelated troupe made another Lemko Wedding movie in 1963 in Yonkers, NY.)

Following Shkimba’s lead, Victor P. Hladick (b. 1873; d 1947), a coalminer who immigrated in 1893, began recording Lemko material for Okeh in June 1928 with the singers Anna Dran (b. New York April 14, 1900; d. July 22, 1989 Passaic, NJ) and Eva Tzurik resulting in about 10 discs and, in the Fall of that year cut three discs for Brunswick including two-sided sketch-with music of a Christening. Over a dozen Lemko performers who had worked with Shkimba in 1928-29 made discs under their own names for Okeh, Brunswick, and Colombia.

Shkimba recorded four more brilliant sides with an expanded band in February for a two disc “Gypsy Wedding” series for Columbia (who, by that time had acquired Okeh) before three final discs in April 1930 in the onset of the Depression and the rise of the radio in replacement of the disc medium as modern home entertainment. Shifting his focus to a 10PM Tuesday night radio show called the Karpato-Russka Hodyna on WLBX from Long Island, Shkimba continued his work, producing and presenting Lemko music. He visited Gorlice country Poland in the late ‘30s, meeting with political activists.

As of 1942, when he registered for the draft for World War II as a 47 year old man, Stefan Shkimba was still working as a streetcar driver in Brooklyn. But it is no exaggeration to say that his vision and his efforts resulted in the documentation of a generation of Lemko-speakers in the U.S. and a deepened sense among them that they, here in America, were not alone and could be heard. The value of that project has resonated over generations after Rusyns of the Carpathians were ethnically cleansed, mainly in forcible resettlement following WWII, from their native territory and subsumed into larger nation-states. The recordings that Shkimba produced nearly a century ago from that first generation of the American diaspora are a window into their 19th century village life and a significant example to the people of the United States, as we continue to contend with questions about immigration, of the cultural brilliance of rural, mountaineering people who made this country their home.

Stefan Shkimba, a man who deeply believed in the value of music and the importance of representation on records, died on Nov. 16, 1966 in Saratoga, New York.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mmm.... School slowly making me go mad challenge but also fury at my lack of sewing skills + fear of failure + fear of injury...

To be clear I'm just having a wardrobe wish moment and went through Etsy and Amazon a min ago looking for pieces. I wanna dress like a Kievan Rus or like an older era Rusyn but the stuff I'd want to wear is either $$$ or needs to be seen myself. ;-;

Or it's just unwearable here in Cali.

...then temptation to get a solid color strap dress and just pin on the brooches... Might also just get some easy bandanas for the Rus headresses and sew/pin the temple rings on there instead of adding the headband.

*sigh* reminds me I need to go buy new shoes...

#random tag#random ramblings#slavic#rusyn#kievan rus#tired#school woes#i swear I'm alive im just not socially alive atm ;-;

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Custom also forbade them to whitewash the walls of the room in which the person died ("in case the soul of the deceased is resting in a crack in the plaster"). The belief in the possible return of the dead was so widespread in the Carpatho-Rusyn homeland that tales on this theme have been retained in all the villages. According to the stories, the late relative most often returned to pick up his or her favorite things, such as a pipe, tobacco, or a musical instrument. These things were usually laid upon the grave in order to prevent any further return of the dead.

Via carpatho-Rusyn.org

This little tidbit pulls at my heartstrings

9 notes

·

View notes