#Romano-Egyptian art

Text

Mummy portrait (wax encaustic on sycamore wood) of a girl, from the Fayum region of Egypt. Artist unknown; ca. 120-150 CE (reign of Hadrian or Antoninus Pius). Now in the Liebieghaus, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Photo credit: Carole Raddato.

#history#ancient history#Ancient Egypt#Roman Empire#Roman Egypt#art#art history#ancient art#Roman art#Egyptian art#Romano-Egyptian art#mummy portrait#encaustic painting#Liebieghaus

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

A Romano-Egyptian Black Basalt Male Portrait Bust

Circa Late 1st Century B.C.-Early 1st Century A.D.

#A Romano-Egyptian Black Basalt Male Portrait Bust#Circa Late 1st Century B.C.-Early 1st Century A.D.#sculpture#bust#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman art

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romano-Egyptian cartonnage mummy mask depicting a female head

ITEM

Romano-Egyptian cartonnage mummy mask depicting a female head

MATERIAL

Linen and Gesso

CULTURE

Egyptian, Roman period

PERIOD

1st Century B.C – 1st Century A.D

DIMENSIONS

208 mm x 200 mm x 200 mm (without stand)

CONDITION

Good condition

PROVENANCE

Ex English private collection, Ex Christie’s, London, April 2000, lot 59 (part lot), Ex Belgian private collection, Ex Bonhams

During the Roman period in Egypt, which spanned from the 1st century BCE to the 4th century CE, a unique blend of Egyptian and Greco-Roman artistic influences emerged. This period saw the production of cartonnage mummy masks that often depicted female heads, showcasing a fusion of traditional Egyptian religious beliefs with the cultural impact of the Roman Empire. Cartonnage was a material made from layers of linen or papyrus soaked in plaster, creating a rigid surface suitable for painting and decoration.

The female heads depicted on these mummy masks during the Roman period often reflected the idealized beauty standards of the time. These masks were not just functional elements for preserving the deceased's features, but also served a ritualistic and symbolic purpose. The depictions frequently incorporated Roman hairstyles and fashion trends, showcasing the blending of cultural elements.

Read the full article

#ancient#ancientart#ancienthistory#artefact#artifact#ancientartifacts#antiquities#antiquity#art#artobject#ancientrome#ancientworld#history#classical#archaeology#roman#egyptian#romano-egyptian#mummy#sarcophagus#female#head#cartonnage

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (1/26/22)

Attributed to the Isidora Master (Romano-Egyptian, active 100-125 CE)

Mummy Portrait of a Woman (100 CE)

Encaustic on linden wood & gilt on linen, 48 x 36 x 12.8 cm.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Scrupulously painted in encaustic wax and enlivened with gilding, every aspect of this Romano-Egyptian portrait identifies its owner as a person of substantial wealth and social position. Isidora’s impressive earrings are distinguished by their unique size and luxurious materials. They consist of a horizontal gold bar suspended from a single pearl; itself suspending four gold vertical bars and each terminating in a pearl. She wears three necklaces connected at the front by an amethyst set into an elaborate gold mount. The topmost necklace appears to be of emeralds, pearls and gold beads, gems characteristically worn by elite women at this time.

For the complete set of 56 Faiyum portraits, visit this MWW Special Collection:

* Ancient/Medieval Art Gallery

vanity=TheMuseumWithoutWalls&set=a.419770264795015

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Mummy Portrait of a Man.

Culture: Romano-Egyptian

Place of origin: Egypt

Date: A.D. 100–125

Medium: Encaustic on wood

#ancient#ancient art#history#museum#archeology#ancient egypt#ancient sculpture#roman#ancient history#archaeology#mummy#mummy Portrait of a man#portrait#fayum#Romano-Egyptian#a.d. 100#a.d. 125

405 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Romano-Egyptian Faience Sculptural Group: Ram with Manger in the Form of a Lotus

Faience, Roman Period, ca. 2nd Century C.E., From Fayum (Medinet el-Fayum)

This charming ram, with its almost prehensile muzzle, feeds from a lotus-form trough. The traditional Egyptian gods Amun of Khnum were identified with curly-horned rams, but by this time several other divinities were as well. In terracotta statuettes and on coins Harpokrates can be seen riding a ram or sitting upon a lotus flower, the latter symbolic of rebirth. Perhaps this faience composition alludes to Harpokrates, who was an immensely popular god of fecundity and rebirth during the Roman era.

With the two faience masks on display with this sculptural group, the ram is said to have been part of a find of numerous faience objects at Arsinoe, capital of the Fayum region.

From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

#ancient egyptian#faience#figurine#2nd century#egyptian#romano-egyptian#sheep#ram#religious art#ceramic

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Romano-Egyptian "mummy portrait" of a bearded man, circa 150-170 CE. A diverse range of elites would either mount such paintings to the front of their coffin or wrap them into their bandages. Getty Villa. Pacific Palisades, CA.

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gold finger ring

Egyptian, Roman Period, probably 2nd century A.D.

Brooklyn Museum

#Ancient Egypt#Roman Empire#Roman Period#ancient art#ancient jewelry#art#gold#ring#finger ring#jewelry#Egyptian#Romano-Egyptian#Brooklyn Museum

399 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Portrait of a Bearded Man from a Shrine’ ( Egypt, A.D. 100 ).

Tempera on wood. Artist unknown.

Image and text information courtesy The Getty.

This image is available for download, without charge, under the Getty's Open Content Program.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Snake Bracelet // Artist: Unknown // Date: 100 BC-100 AD // Material: Gold

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Egyptian deity Horus as a Roman emperor. The figure bears the falcon-head of Horus, topped by the characteristic double crown (pschent) of Egyptian pharaohs, but also wears Roman armor (specifically lorica squamata, consisting of metal scales sewn to a fabric backing) with a small gorgoneion. Artist unknown; 2nd cent. CE. Now in the Louvre. Photo credit: © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons /

CC-BY 4.0

#classics#tagamemnon#Ancient Rome#Roman Empire#Egypt#Ancient Egypt#art#art history#ancient art#Egyptian art#Ancient Egyptian art#Roman art#Ancient Roman art#Roman Imperial art#Roman Egypt#Romano-Egyptian art#Horus#Egyptian religion#Ancient Egyptian religion#kemetic#syncretism#sculpture#statuette#figurine#metalwork#bronze#bronzework#Louvre#Louvre Museum#Musee du Louvre

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Romano-Egyptian Group of Millefiori and Mosaic Glass Beads

Circa 1st Century B.C./4th Century A.D.

Strung as a necklace, including faceted cylindrical beads with floral motifs, two ovoid beads with opaque yellow and red eyes in a translucent green matrix, and a large biconical bead with feather pattern, the gold spacer beads probably of later origin.

Length 43.2 cm.

#A Romano-Egyptian Group of Millefiori and Mosaic Glass Beads#Circa 1st Century B.C./4th Century A.D.#art#artist#art work#art news#jewelry#ancient jewelry#roman jewelry#egyptian jewelry#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mummy Portrait of a Woman

An inscription in Greek gives her the name of ICIΔOPA (Isidora), and she would've been of high social and economic standing, as indicated by both her attire and the care, effort, and material used when creating this portrait.

Romano-Egyptian, 100 CE.

#this was created in egypt#btw!#ancient egypt#egyptology#egyptian history#romano-egyptian#roman history#ancient rome#ancient history#history#artifact#classics#greek#ancient art#anthropology#archaelogy#leguinian

0 notes

Photo

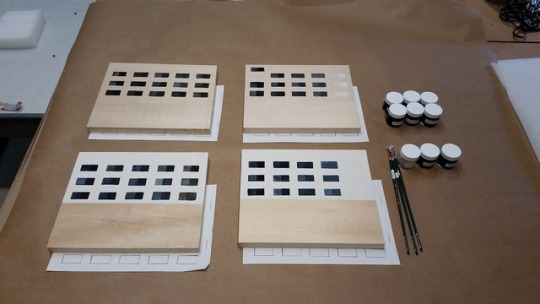

Over the last few weeks, pre-program conservation interns Natasha Kung and Meredith Menache have been making custom paint swatches according to historic procedures. Although the tools they use are up to modern standards of practice – their gloves, masks, and clean glass beakers, for instance – the paint materials themselves and the methodology used are similar to those of artists making Romano-Egyptian funerary portraits (fayum portraits) about 2000 years ago. Dry pigments are mixed with water for form a paste then blended with a binding medium. Natasha and Meredith apply each type of paint mixed to a board that has also been prepared using historic materials and practices.

Conservators are particularly interested in paint made with indigo for this project. Since indigo was often used in a mixture with other pigments (adding orpiment makes green; adding madder makes purple), each board of paint outs that Natasha and Meredith create includes indigo mixed in different proportions with a different historic pigment. So far they have worked on mixtures with vine black and with gypsum. The binding media for the paint is also varied to include the range of options found on the Brooklyn Museum’s fayum portraits: each board will show the pigment mixtures applied using three different types of animal-based glue and two different types of wax.

The goal of this highly methodical process is to learn more about one of the analytical imaging techniques recently adopted at the Brooklyn Museum, used in the characterization of indigo. Studying known mixtures of indigo in a variety of binding media on these boards will help conservators know what information is most reliable when studying the fayum portraits using the same imaging techniques. In the next few months, conservators and interns will complete these paint outs and conduct the imaging. Stay tuned for the progress of this project!

Posted by Jessica Ford

#bkmconservation#conservation#art conservation#art conservators#conservator#painting#paint#swatches#fayum portrait#ancient#romano-egyptian#funerary#indigo#orpiment#science#art#highlight

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

~ Mummy Shroud with Painted Portrait of a Boy.

Culture: Romano-Egyptian

Place of origin: Egypt

Date: A.D. 150–250

Medium: Tempera on linen.

#ancient#ancient art#ancient egypt#ancient roman#ancient portrait#mummy shroud#painted portrait#boy#bird#Romano-Egyptian#Egypt#egyptology#egypt#roman Period#tempera#a.d. 150#a.d. 250#2nd century#3rd century#history#archeology#museum

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

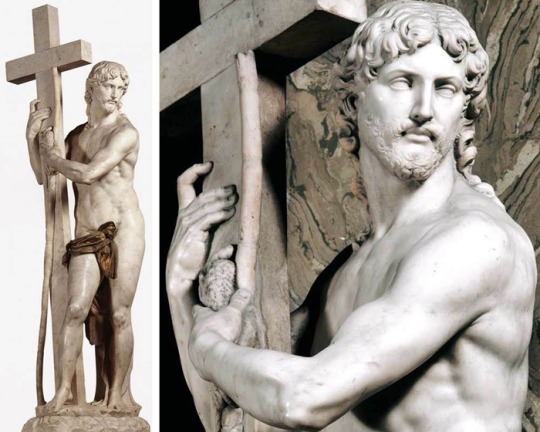

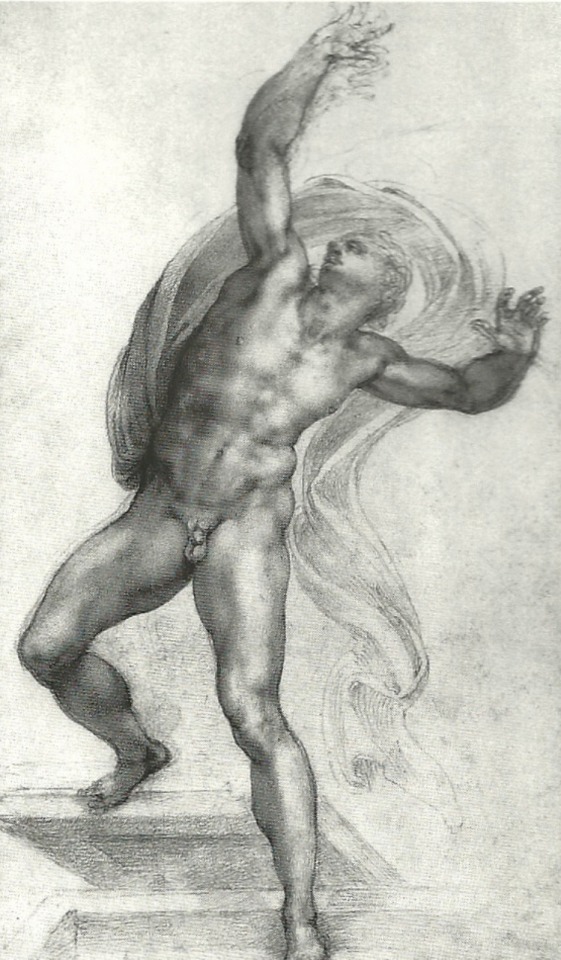

Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ: Discovering the sacred in the profane.

The true work of art is but a shadow of the divine perfection.

- Michelangelo Buonarroti

While a visit to Rome’s grand squares like Piazza Navona is at the top of everyone’s list, there is much more to the Eternal City. The Piazza della Minerva, is one of Rome’s more peculiar squares and is a must-see for lovers of Bernini’s work.

As one of the smaller squares in Rome, Piazza della Minerva holds some interesting sites. Built during Roman times, the square derives its name from the Goddess, Minerva, the Roman Goddess of wisdom and strategic warfare. During the 13th Century, the decision was made to build a Christian Church on top of what was once a square dedicated to a pagan Goddess – and so the church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva was born, a beautiful example of Gothic architecture and Rome’s only Gothic church.

In fact this is the only Gothic church in Rome. It resembles the famous Church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. There are three aisles inside the church. The soaring arches and the ceiling in blue are outstanding. The deep blue colours dominate the structure while the golden touches promote the intricate design. There are paintings of gold stars and saints. The stained glass windows are beautiful too.

In the centre of the Piazza is an elephant with an Egyptian obelisk on its back, one of Bernini’s last sculptures erected by Bernini for Pope Alexander VII and possibly one of the most unusual sculptures in Rome. There are several theories which aim to decipher Bernini’s inspiration for the sculpture, some of which point to Bernini’s study of the first elephant to visit Rome, while others point to a more satirical combination of a pagan stone with a baroque elephant in front of a Christian church.

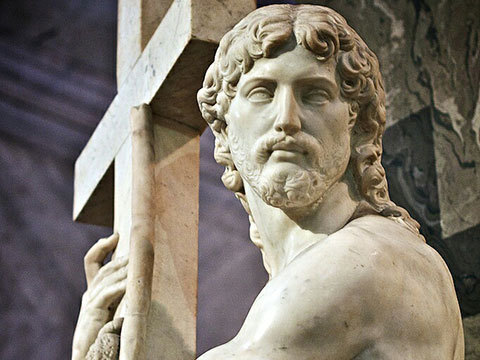

Tourists flock to see the elephant but more often than not they miss out visiting an almost forgotten marble masterpeiece by Michelangelo himself inside the church. This controversial statue has resided in the Santa Maria sopra Minerva Church in Rome for almost five hundred years. Indeed The Risen Christ by Michelangelo is one of the artist's least admired works. While modern observers frequently have found fault with the statue, it satisfied its patrons enormously and was widely admired by contemporaries. Not least, the sculpture has suffered from the manner in which it is presently displayed and from biased photographic reproduction that emphasises unfavorable and inappropriate views of Christ.

Around 2017 I was fortunate on a visit back to London to see once again Michelangelo’s marble masterpiece, The Risen Christ, which was being displayed in all its naked glory at an exhibition at the National Gallery.

This was another version of this great sculpture that no one has got round to covering up. It has just come to Britain. Michelangelo’s first version has been lent to the National Gallery, in London, for its exhibition Michelangelo and Sebastiano del Piombo in 2017. It came from San Vincenzo Monastery in Bassano Romano, where it languished in obscurity until it was recognised as Michelangelo’s lost work in 1997.

I found it profoundly moving then as I had seen the other partially clothed one on several visits to the church in Rome. It has always perplexed me why this beautiful work of art has been either shunned to the side with hidden shame or embarrassment when it holds up such profound sacred truth for both art lover or a Christian believer (or both as I am).

Michelangelo made a contract in June 1514 AD that he would make a sculpture of a standing, naked figure of Christ holding a cross, and that the sculpture would be completed within four years of the contract. Michelangelo had a problem because the marble he started carving was defective and had a black streak in the area of the face. His patrons, Bernardo Cencio, Mario Scapucci, and Metello Vari de' Pocari, were wondering what happened when they hadn't heard for a while from Michelangelo. Michelangelo had stopped work on The Risen Christ due to the blemish in the marble, and he was working on another project, the San Lorenzo facade. Michelangelo felt grief because this project of The Risen Christ was delayed. Michelangelo ordered a new marble block from Pisa which was to arrive on the first boat. When The Risen Christ was finally finished in March 1521 AD Michelangelo was only 46 years old.

It was transported to Rome and this 80.75 inches tall marble statue was installed at the left pillar of the choir in the church Santa Maria sopra Minerva, by Pietro Urbano, Michelangelo's assistant (Hughes, 1999). It turns out that Urbano did a finish to the feet, hands, nostrils, and beard of Christ, that many friends of Michelangelo described as disastrous). Furthermore, later-on in history, nail-holes were pierced in Christ's hands, and Christ's genitalia were hidden behind a bronze loincloth.

Because people have changed this sculpture over time; many are disappointed with this work of art because it is presently different than the original work that Michelangelo made. The Risen Christ had no title during Michelangelo's lifetime. This sculpture was given the name it has now, because Christ is standing like the traditional resurrected saviour, as seen in other similar works of art.

It was in discussion with an art historian friend of mine currently teaching I was surprised through her to discover the sculpture’s uncomfortably controversial history. There is no doubt Michelangelo’s marvellous marble creation has raised robust debates about where beauty as an aesthetic sits between the sacred and the profane. And nothing exemplifies that better than the phallus on Michelangelo’s The Risen Christ.

For the majority of its time there, however, the phallus has been carefully draped with a bronze loincloth - incongruous at best, and prudish at worst, but either way a less than subtle display of the historic Church’s discomfort with the full physicality of Christ.

Indeed, it is worth noting that this attitude prevails, at least in some sense, into the twentieth-century: the version of the statue in Rome remains covered to this day, and much of the critical attention the sculpture has received after Michelangelo’s death has been grating. Romain Rolland, an early biographer, described it as ‘the coldest and dullest thing he ever did’, whilst Linda Murray bluntly dubbed the work ‘Michelangelo’s chief and perhaps only total failure’.

But Michelangelo himself saw no such mistake. The censored statue seen in Santa Maria sopra Minerva is what we might call his second draft.

It’s interesting to note that when artist was originally commissioned to sculpt a risen Christ in 1514, he had all but completed it before realising that a vein of black marble ran across Jesus’ face, marring the image of classical perfection which he so wished to emulate. It had nothing to do with the phallus. Furious, Michelangelo abandoned this Christ - the one I saw at the National Gallery - and began again. Even given a fresh chance, he chose to retain Christ’s complete nudity.

Why was this of such importance to Michelangelo? Why did he so strongly wish to craft the literal manhood of Christ, as never depicted before? Part of the answer may lie in his historical context: the Renaissance in Italy was driven in the part by the remains of Roman antiquity discovered there; study of the classics became commonplace, and scholars tended to consider the Graeco-Roman world as a cultural ideal, with ancient art in particular being emblematic of a lost Golden Age. Famously, classical sculpture was almost always nude.

In his interview with The Telegraph in 2015, Ian Jenkins, curator of the British Museum exhibition “Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art”, attempted to explain this tradition. ‘The Greeks … didn’t walk down the High Street in Athens naked … But to the Greeks [nudity] was the mark of a hero. It was not about representing the literal world, but a world which was mythologised.’

We see evidence for this trend in Greek literature as well as sculpture: Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, considered by some to be the earliest known works of Western literature, were likely written between the 8th and 7th centuries BC, but their setting is in Mycenaean Greece in the 12th century. The Greeks believed that this earlier Bronze Age was an epoch of heroism, wherein gods walked the earth alongside mortals and the human experience was generally more sublime. In setting the texts at this earlier stage in Greece’s history, Homer echoes the belief held within his contemporary society that mankind had been better before (what we might now call nostalgia, or, more colloquially, “The Good Old Days syndrome”). There is a real feeling of delight present in the distance Homer creates between his actual, flawed society, and the idealised past.

Indeed, it calls to mind a line I once read in an introduction to L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between, by Douglas Brookes-Davies: ‘Memory idealises the past’. Though modernist texts such as The Go-Between problematise this, in antiquity it was not only commonplace but celebrated to look back to a more perfect existence and relive it through art. The very fact that Michelangelo abandoned his sculpture after years of work on account of a barely noticeable flaw in the marble is evidence that he, too, was striving towards the classical ideal of perfection. ‘Unfortunately,’ Hazel Stanier has commented, ‘this has resulted in unintentionally making Christ appear like a pagan god.’

This opens up another question – why does such a rift exist between the way ancient cultures envisaged their divinity and our own conceptions of a Christian God? Why are we not allowed to anthropomorphise the deus of the Bible in the same way that the Roman gods were?

Christ, of course, makes this somewhat confusing, given that he is described in the Bible as ‘the Word made flesh’, a physical and very human incarnation of the spiritual being that we call God. Theology tells us that he is fully human and fully divine, and yet the Church have excluded him from many aspects of life that a majority of us see as typifying a human being. Christ has no apparent sexual desires or romantic relationships, and though not exempt from suffering, he does not play any part in sin (which, as the saying goes, is ‘only human’). I think that the enormous controversy caused by films such as The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), which explore the possibility of Jesus having a sex life, is reflective of the possibility that - though in theory the Christian messiah is fully human - we feel significant discomfort at the notion that he may have explored particular aspects of the human experience.

Purists and the prude and liberals rush to opposite sides of the debate. If purists run one way to completely deny Christ had any sexual desires or even inclinations as all humans are want to do, liberals commit the sin of rushing to the other extreme end and presuppose that Jesus did act on sexual impulses simply because it was inevitable of his human nature.

I think the truth lies somewhere between but what that truth might actually be is simply speculation on my part. It doesn’t detract for me the life and saving mission of redemption that Jesus was on - to suffer and die for our sins as well as the Godhead reconciling itself to sacrificing the Son for Man’s sins and just punishment.

Of course, it is well-known that the classical gods had no qualms about sexual activity. It is difficult to make retrospective judgements about citizens’ opinions on this but, as it was the norm, we might assume that they felt it was rather a non-issue. I can empathise with some critics who reason that the Christian God is not entitled to sexual expression is because of the traditional Christian idea that sex is inherently sinful – that original sin is passed on seminally and so by having sex we continue to spread darkness and provoke further transgression. It is from this early idea that theological issues such as the need for Mary to have been immaculately conceived (she was not created out of a sexual union, much like her son) have stemmed. But here - the immaculate conception - the critics are profoundly wrong in their theological understanding of why God had to enter the world as Immanuel in this miraculous way.

Some Christian critics - and I would agree with them - assert that the vision of a naked Christ might make a powerful theological point in a world where sex still carries these connotations. They rightly point out that clothing - and I might extend this to mean the covering-up of the sexual parts of our body - was only adopted by humankind after the Fall, the nudity of Christ is making a statement about his unfallen nature as the second Adam. In other words, Christ has no shame, because he is sinless and has no need for shame. Perhaps what Michelangelo intended was actually to disentangle nudity from its sexual, sinful associations, instead presenting us with a pre-lapsarian image of purity taking the form of the classical Bronze Age hero.

There is another, less theological explanation for the sculptor’s obvious use of the classical form. It reminds us of a time when gods walked the earth alongside us, when they were fully human – us, only immortal. Maybe he wanted to emphasise that fully human aspect of Christ’s being. Questionable as much of their behaviour was, the classical gods were certainly easy to identify with. For Michelangelo, this may have been his own way of embodying John 1:14 in marble: ‘The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us’.

It is here critics may have gotten hold of the wrong end of the stick with The Risen Christ when they point out the odd proportions of the figure: that it has a weighty torso, or the broad hips atop a pair of tapered and rather spindly legs, or even a side or rear view of the figure that show Christ’s buttocks.

For a start, this ungainly rear view was not supposed to be seen. The statue was meant to go in a wall niche, so that the back of the statue was hidden. Michelangelo of course knew this, and shaped the statue so that it would appear well proportioned from the front. If we view the sculpture from the front left, perhaps its best side, then Christ is no longer a thickset figure. Rather, his body merges with the cross in a graceful and harmonious composition.

The turn of Christ’s body and his averted face suggest something like the shunning of physical contact that is central to another post-Resurrection subject, the Noli me tangere (“Touch Me Not”). The turned head is a poignant way of making Christ seem inaccessible even as the reality of his living flesh is manifest.

We are encouraged to look at not Christ’s face, but the instruments of his Passion. Our attention is directed to the cross by the effortless cross-body gesture of the left arm and the entwining movement of the right leg. With his powerful but graceful hands, Christ cradles the cross, and the separated index fingers direct us first to the cross and then heavenward. Christ presents us with the symbols of his Passion – the tangible recollection of his earthly suffering.

Behind Christ and barely visible between his legs we see the cloth in which Christ was wrapped when he was in the tomb. He has just shed the earthly shroud; it is in the midst of slipping to earth. In this suspended instant, Christ is completely and properly nude.

We must imagine how the figure must have appeared in its original setting, within the darkened confines of an elevated niche. Christ steps forth, as though from the tomb and the shadow of death. Foremost are the symbols of the Passion, which Christ will leave behind when he ascends to heaven.

Why was Michelangelo compelled to portray Christ completely naked in a way that was bound to trouble some Christians? It was not out of a desire to blaspheme. On the contrary, this genius – poet, architect and painter as well as the greatest sculptor who has ever lived – was not only a faithful Christian but someone who thought deeply about theology. You can bet he had good religious reasons to depict Christ in full nudity.

But it would be complacent to think there was no tension in showing Christ nude. The fact that The Risen Christ in Santa Maria still has its covering proves how real those tensions are. The fundamental reason Michelangelo could get away with it was that he was Michelangelo. By the time he created this statue, he had the Sistine Chapel ceiling (with all its male nudes) under his belt and was the most famous artist in the world.

For centuries, the faithful have kissed the advanced foot of Christ, for like Mary Magdalene and doubting Thomas, they wish for some sort of physical contact with the Risen Christ. To carve a life-size marble statue of a naked Christ certainly was audacious, but it is also theologically appropriate. Michelangelo’s contemporaries recognised, more easily than modern viewers, that the Risen Christ was a moving and profoundly beautiful sculpture that was true to the sacred story.

#the risen christ#michelangelo#marble#church#christian#beauty#aesthetics#statue#religious#renaissance#history#rome#bernini#art#arts#culture#society#religion#sculpture

201 notes

·

View notes