#Quenya

Text

Now this is a real dealbreaker 💔

#nerdy girls#sexy nerd#nerd girl#nerdy chicks#lovely legs#lord of the rings#girls in sneakers#tolkien#girls in yoga pants#strong legs#great legs#female legs#beauty legs#yoga shorts#short shorts#the hobbit#lotr movies#lotr#quenya#sindarin#lotr elves

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

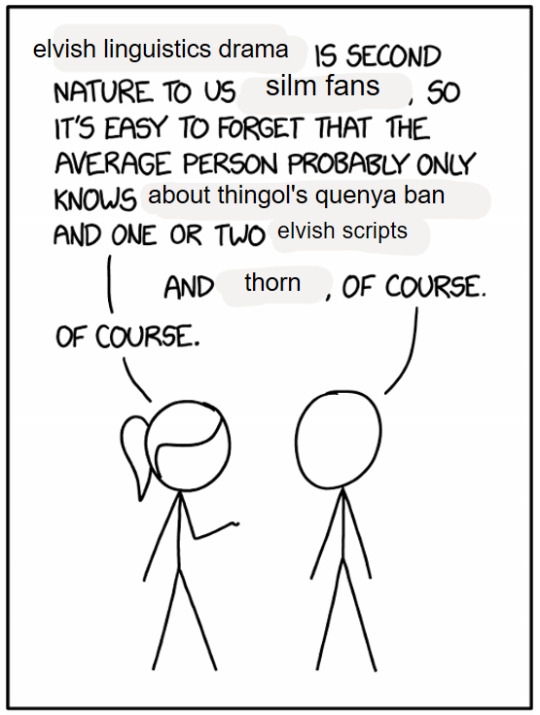

in reference to this post:

admittedly i'm not the right person to make this meme since i'm not really well-versed in the lore lol

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

My toxic trait is that when I encounter the ‘Fëanorian lisp’ in a fanfiction I’ll go check the root of the word to make sure it was originally written with a Þ and it is not a linguistic abomination. For example: Þauron is correct since the archaic form is Thaurond, but saying Þilmaril would send Fëanor in a fiery fit of anger.

450 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hc in my au:

Thranduil doesn’t speak Quenya, but he does speak Primitive Quendian bc he was literally there when that was still the language used, so while he doesn’t understand exactly what people are saying when they speak in quenya, he does get the gist of it using context clues.

The thing is, no one realizes it, so sometimes some noldor elves are talking in quenya, talking shit in front of him, thinking he can’t understand them, but he can. He’s been wanting to drop that little tit bit of information forever, but he can only do it once, so it has to have the largest impact as possible.

Naturally, he replys to something galadriel said in quenya in sindarin, knowing exactly what the conversation was about, in the middle of a banquet, and he could see half the elves present go through the 5 stages of grief right then and there as galadriel reboots her systems.

#thranduil#lord of the rings#lotr#lotr elves#the hobbit#silmarillion#quenya#primitive quendian#lake cuivienen#pre orome days#4 silvan sibs au#shamelessly pushing my ‘miriel and thranduil are twins agenda’#house of edireth

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Tolkien's languages#quenya#sindarin#tolkien legendarium#tolkien#silmarillion#lord of the rings#lotr#lotr rop#lotr trop#fantasy#jrr tolkien#the hobbit

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

Idea for the poll submitted by anonymous – slightly altered.

#middle-earth#middleearth polls#tumblr polls#tolkien#the silmarillion#Silmarillion#Quenya#Shibboleth#category: pick something#I hope the minor adjustments are ok for you anon

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

recently translated 'he chanted a song of wizardry...' to quenya so here's finrod vs sauron battle and some tengwar ~calligraphy

222 notes

·

View notes

Text

There was a post going around for a while about how kana means chicken in Finnish, making Kanafinwe = chicken Finwe. The thing is, a lot of Quenya names have te reo Māori meanings or can have funny meanings when transliterated into te reo. I've made a little list.

The most important thing to know is that 'wh' is pronounced 'f' in most dialects. Also, I took several liberties with the transliterations - when there were multiple options, I picked the one whose meaning I liked the best.

Translations

Maitimo: Māītimo means sour gardening tool. (Māī = sour, timo = a tool used to dig up sweet potatoes.) But if you're willing to mess around with the vowel sounds a little ... Māī-iti-mau [my-ee-tee-mo]* = to be a little sour to be captured.

*'au' is usually pronounced like the o in no.

Kanafinwe: Kana = wild stare / to stare wildly, making him Wild Stare Finwe.

Kano: either 1) colour or 2) bean.

Turukano: tūru means chair, so Tūrukano means chair bean

Ingo means desire, yearning, wanting. (Ingoldo becomes Ingoroto, a desire/yearning within.)

Amarie: Amārie = of peace, tranquility.

Arafinwe: ara means the waters breaking in childbirth. It also means path, but the first option is funnier.

Arakano: path bean

Angamaite: anga = to face, māī = sour, and tē = fart.

Curufinwe: Kuru has a lot of meanings including to hit/punch, to be tired, a piece of greenstone jewelry, or a mallet. So I guess that makes his name Tired Finwe, Ornamental Finwe, Mallet Finwe, or Punch Finwe. The last one would be in the imperative, making it a command.

Moringotto: we have to take out one of the t's to make this Mōringoto. It means either 1) intense unimportant person or 2) unimportant person to penetrate.

Transliterations

Feanaro: The best transliteration would be Wheanaro, which is pronounced the same as in Quenya. But my favourite interpretation is Whaea-ngaro; mother lost/missing.

(Edited to add that 'ng' is a soft sound pronounced like in sing. I'm cheating a bit here, because it's actually the equivalent of the Quenya ñ, not n like in Feanaro.)

Nelyo: We don't typically have l or y sounds. My preferred option for this would be Ngērō, meaning to scream inside.

Nelyafinwe -> Neriawhine or Nerawhine. Nera can mean nail (as in a metal nail) or to nail. Whine [fee-neh] isn't a word in most dialects, but in some very small areas it's the word for woman/women.* (In most areas the word is wahine.) So uhhhhh interpret that as you will, but this may be the single most ironic name on the list.

*Another possible transliteration of Finwe would be Whinewē, meaning woman liquid. This is physically painful to me so I'm sticking with Whine.

Findekano: In the same vein, Whinekano means bean woman or woman bean. If you prefer Whine-te-kano or Whine-tē-kano, the former means Woman The Beans and the latter means women fart beans.

Turko is Tūrukau: chair cow / nothing but a chair.

Makalaure could become Makarōre. Maka = to throw/fling and rōre = lord, making the full name Yeet Lord. A prophetic mother name.

Tyelkormo would become Terekomo. Tere= swift/fast. Komo... um. This is mostly used to describe putting on clothes. But it can also mean to thrust or insert. So basically the same as the Quenya

Moryo = Mōriau, a firm unimportant person / a howling unimportant person.

Curvo: if written as Kuruwau, in certain dialects it would mean hit me.

Pityo would be Pitiau: defeated smoke/mist.

Findarato: rātō means western, so Whinerātō = western woman.

There are also names that are pronounced the same in te reo Māori as they are in Quenya but have no Māori meaning, e.g. Anaire or Curumo.

Take this whole thing with a pinch of salt, because obviously we don't usually make word-for-word translations of transliterated names. Like I said, I've also taken some liberties with the transliterations. But to the best of my knowledge, all of these are accurate translations.

It's the House of Finwe uwu smol beans

#silmarillion#quenya#my nonsense#māori-fying tolkien#don't mind me mushing together different dialects

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Question towards the silm fandom: Do you guys adress some elven characters by their quenya names too? Like saying "Irisse" instead of "Aredhel" and "Nolofinwe" instead of "Fingolfin". I do this very often accidentally without noticing because it just feels natural to say the quenya names.

I really want to know if i'm the odd one out here bc i havent heard of anybody else do this.

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Languages and Linguistics of Middle Earth

Gin suilannon!

In the context of my minor programme in Celtic studies and languages, I am following a course called From Táin to Tolkien and Beyond, and today, we had a guest lecture about the languages of Middle Earth, more particularly Sindarin. Since it might be useful to some of you (out of curiosity or for your fanfictions), I thought I would share my notes and my conversations with the guest lecturer here.

This was a very linguistics-driven lecture, so I will try to add explanations where I can and, hopefully, make the information more accessible. If you have any questions, you can react to this post or DM me! And beware, this is a very long post.

So, without further ado, here is what I learnt.

✽ Notes on Historical Linguistics, Manuscript Tradition and the Languages of Tolkien's Middle Earth by Dr. Aaron Griffith

✣ Shared histories of languages and manuscripts are often visualised with tree diagrams to see the evolution and how they branch out

✣ Little material was published about Middle-Earth and the Elves during Tolkien's lifetime

-> Most of it is part of the Legendarium

-> Main periods of writing (here we only mentioned the writing processes or when a project was finished, not when they were published):

- The Lost Tales (1916-1926): infancy of the Elvish languages

- Sketch of The Silmarillion (1926-1930): revision of The Lost Tales and some changes brought to Elvish

- Quenta Noldorinna (1930): further reworking and significant expansion of the sketch

- The Hobbit (1933): originally intended as an unrelated story

- Quenta Silmarillion (1937): fullest expansion of The Lost Tales and significant refinement of the languages

- The Lord of the Rings (1950s): use of the mythology of all the earlier writings as a basis, reworking of the languages and massive changes in their interrelations

- The Silmarillion (post-1948): based on Quenta Silmarillion, which was heavily revised after The Lord of the Rings

✣ Tolkien rarely dated his works and compositions, so it is difficult to establish a precise creative process or linear chronology of the changes brought to Middle Earth. However, he did leave us some clues:

- Absolute Dating -> occasionally, Tolkien did attach dates to his manuscripts, but it remained a rare occurrence

- Relative Chronology -> some compositions are dependent on changes to earlier works, so a logical chronology can be estimated (this can also be made possible by the scrap papers from Tolkien's personal records and drafts)

- Handwriting -> can be misleading, but it can be a helpful tool to date pieces of distinctly different chronological layers

- Nomenclature -> Tolkien frequently changed character names, so particular names can be matched with letters and extracts in which they appear

- Christopher Tolkien -> his manuscript order from the twelve-volume The History of Middle-Earth series

✣ Critical asymmetry -> languages frequently split into dialects and other languages of their own, but when manuscripts are retraced according to their version of the same text (think of Arthurian romances and oral tradition being recorded at different points in time and therefore presenting different themes or characters), narratives (stories) cannot be regrouped as easily

-> However, there are 2 relations between stories and languages:

1. How changes can propagate in a language system or narrative tradition

2. The relations of language families in real- (at the time of composition) or book-time (time as it passes in the stories)

✣ In natural language, change moves forward in time. This is a trend which also applies for errors in manuscript copies (irregularities in tropes, character changes, etc.)

✣ In stories, a plot development can be carried forward just like a sound can evolve in a language. However, change can occur backwards, too. For example, if a character's ancestry is modified, this can change the whole manuscript history of the story being written (by this, understand that the story must be readapted to fit the new information to maintain some consistency).

✣ Historical linguistics is concerned with the study of language change and the formation of language families (Romance languages, Germanic languages, Slavic languages, etc.). It does so by examining and comparing systems from different languages to see if they can be retraced to an original, common system (Welsh and Irish stemming from Proto-Celtic, for instance).

✣ Some of Tolkien's languages were intended to be related. The following languages and dialects are related in a clear, 'historical' structure, which mimics the way that languages evolve in our world:

- Quenya

- Sindarin

- Lindarin

- Noldorin

- Telerin

- Doriathrin

- Ilkorin

✣ Elvish languages were constantly revised by Tolkien, making it challenging to determine a single 'history' (or creative process) of Elvish tongues. In their case, it is more accurate to speak of a series of histories or continua, which refer to the times at which Tolkien brought significant changes (often 1916, 1937 and post-1948). A tree diagram is thus no longer fitting to visualise them all. The diagrams overlap in a three-dimensional visualisation instead, with each layer representing the changes of each major revision.

✣ Some changes were brought solely for aesthetic purposes. Tolkien found the phonetics of Welsh and Finnish particularly pleasing to the ear and, therefore, based Sindarin and Quenya on their structures. As you probably already know, these are the two most-developed languages in the lore of Middle Earth, but he fleshed out at least four other Elvish languages (Telerin, Ilkorin, Doriathrin and Danian). There were generally more changes in Quenya (abbreviated Q).

✣ What was originally Noldorin (abbreviated N) in the 1916 and 1937 versions is now Sindarin (abbreviated S). After 1948, Noldorin became a dialect of its own, and its place in the language tree shifted. The terms and grammar remained rather consistent from one version to the next.

-> example:

1916: N Balrog 'fire demon' (bal- 'anguish' + -róg 'strong')

1937: N Balrog 'fire demon' (bal- 'torment' + rhaug 'demon')

1948: S Balrog 'demon of might' (bal- 'might' + raug 'demon')

✣ Such modifications reflected the major changes brought to the stories (especially to what we now know as The Silmarillion), but they also mirror the natural linguistics evolution of real-life languages. This causes a problem, namely in the emergence of 'linguistic orphans', or words whose etymology was no longer valid because the linguistic or sound laws that birthed them in the first place were removed.

-> example: Eärendil (Q 'lover of the sea', ayar- 'sea' + -ndil 'lover')

1916: eären was the genitive form (or possessive form) of eär, so the compound made sense.

1937: eäron replaced eären, but Tolkien remained particularly attached to the previous version because of the Old English éarendel -> this created a disruption in etymology, so he declared that eär/eären meant 'sea'

✣ Major sound changes introduced with The Lord of the Rings

✣ Tolkien introduced lenition in some grammatical cases. In Celtic languages, it is a rather common occurrence. It consists in the softening of a consonant at the start of a word according to certain rules. For example, the sound [p] is softened into a [b]. My knowledge of Irish is non-existent, but it is something which happens in Middle Welsh (c.1100-c.1400) and Modern Welsh.

-> example: before 1972, Tolkien suggested that the name Gil-Galad ('star of brilliance', 'brilliant star') was lenited, which means that the second component of the name stems from the word calad (lenition causes the c to soften into a g).

-> However, he stated in a letter in 1972 that lenition no longer occurred if 'the second noun functions as an uninflected genitive' (in other words, that the possessive is not marked with an apostrophe, 'of the', or any other marker that applied in Sindarin). This explains the merging of ost 'start' + giliath 'fortress' into Osgiliath 'fortress of the start'. If giliath was lenited, the name would instead be Osiliath or Ostiliath (when lenited, g disappears at the head of the noun).

-> There is one noted inconsistency regarding the 'rule' above, and it is the case of Eryn Vorn 'Dark Forest'/'Forest of Darkness'. Eryn is a plural form of oron 'tree' and morn acts as a noun (but it is usually the adjective for 'black, dark' and morne is the noun referring to 'darkness, blackness'). Due to Welsh vowel change rules in certain plural forms, morn becomes myrn, and this very same plural form should accompany eryn (both adjective and noun adopt a plural form). Instead, we find a singular form of morn which is lenited (m becomes v). This is possibly an error accidentally left in by Tolkien.

✣ The nature of Noldorin/Sindarin makes Elvish languages rather realistic in their evolution compared to real-life languages, because irregularities occur. Dr. Griffith argues that languages naturally show irregularity because of gradual changes and borrowed words, but he acknowledges that accidents are sometimes just that. Accidents.

✽ Notes on the lecture by Dr. Aaron Griffith

✣ A general interest in creating new languages emerged in the 19th century. It was believed to be a tool which could help resolve political conflicts by creating a sense of cohesion and avoiding miscommunication. This is evident in the creation of Esperanto.

✣ In most cases of invented languages, the language was invented first, and the world or context they belonged to was formed from there. Tolkien worked exactly the other way around.

✣ Tolkien aimed to create an English myth, because he considered that England lacked its own mythology. King Arthur is generally considered Celtic in essence (possibly Welsh) and therefore could not apply as an English myth. This could explain why he retained the Gregorian calendar throughout The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. It served as a familiar bridge between Middle Earth and England/the real world.

✣ In original maps of Beleriand, there used to be land west of Ered Luin (the Blue Mountains northwest of the Shire). This was changed in later maps, which Tolkien designed and drew himself. Often, Arda was depicted as a globe with several continents. Afterwards, Tolkien decided that Arda was, in fact, flat.

✣ Backstory of the Elves (I have no knowledge of The Silmarillion, so if I did not use the right terms or names, please feel free to correct me!):

- Elves first came into existence in Cuiviénen and were invited by the Valar to join them in Valinor, meaning that they had to cross the continent and the ocean

- Not all Elves made it to Valinor, however. Some decided to separate from the main group and settled in different areas of Middle Earth, like in Greenwood (later known as Mirkwood). This caused the language they spoke to evolve into different dialects and, sometimes, completely separate languages

- Elves returned to Middle Earth after the war against Morgoth (S; Q Melkor), aided by Númenorians

- The West was physically separated from the rest of Arda by a 'cut' through the ocean. The gods then shaped Arda into a globe, but once past the portal to the Undying Lands, it was flat again.

✣ Most often, Tolkien did not provide translations of the phrases he peppered into his works, mostly because he believed that nobody would be interested in them. Once he received enthusiastic letters from readers, he decided to attach them to later versions. He did regret publishing the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, however, because the changes felt too 'final' and he felt as though he took away his own liberty to make further revisions to the material (once it's published, you cannot go back).

✣ Tolkien created quite a lot of poetry to match the phonological aesthetics of Sindarin and Quenya.

✣ Outside The Lord of the Rings, the longest source we have in Sindarin is The King's Letter, which was originally supposed to be part of the epilogue in The Return of the King but was not in the final version because he wrote it in the 1970s. In this letter written entirely in Sindarin, Aragorn (then King Elessar) invites Sam, Rosie, and their children to visit him and Arwen in Minas Tirith.

✣ Sindarin grammar is tricky to reconstruct because of the lack of sources on the matter and the complicated grammar revisions that Tolkien brought. However, we do know that it is loosely based on Welsh, which he confirmed in 'English and Welsh' in The Monsters and the Critics (published posthumously in 1983). He aimed to recreate the same 'pleasant' sounds that he found in Welsh for Sindarin. If the reader knows how to pronounce the Welsh alphabet, then they can easily pronounce Sindarin.

✣ Secondary sources on Sindarin:

- A Gateway to Sindarin by David Salo. Salo worked as a language consultant on the films, but his book has been criticised by Tolkien scholars because it tends to ignore the changes between 1937 and 1948 and it treats Noldorin as a dialect of Sindarin, which is no longer the case from 1948 onwards.

- The Languages of Tolkien's Middle-Earth by Ruth S. Noel

✣ Primary sources are very incomplete, but the main ones we can use to observe the language are the following publications:

- The Lord of the Rings

- The Lost Road and Other Writings

- The War of the Jewels

- The Peoples of Middle-Earth

✣ As established in the previous section, Sindarin follows some of the grammatical rules present in Welsh and pre-modern Welsh. We encounter mutations, especially lenition (also called 'soft mutation' because of the sounds becoming softer, e.g. p becoming b), and they play a crucial role in the structure of Sindarin. Below is a comparison of soft mutation/lenition in the context of Welsh and then in Sindarin.

-> Welsh: dyn 'man' + teg 'attractive' = dyn teg 'attractive man'

merch 'girl' + teg 'attractive' = merch deg 'attractive girl' -> soft mutation after a feminine noun, t is softened into a d

-> Sindarin: Perhael 'Samwise' (literally 'half-wise')

Berhael 'Samwise' -> lenition when used as a direct object in a clause, p softened into a b

Carm Dum 'Red Valley' (capital of Angmar) -> uses tum 'valley', but it is lenited when acting as an adjective or an adverb, t softened into a d

✣ Other forms of mutations exist in Sindarin, but this part of the lecture is quite technical and does require a basic knowledge of Welsh or Middle Welsh to be comprehensible. Feel free to message me if you wish to know more about them.

✣ Mutations arose from sound changes that affected phrases (intonational units). In other words, they are groups of words that have a single principal accent (or stress) to fluidify the manner of speech and convey a sense of emphasis. For instance, not every word is stressed separately in the sentence 'I am going to the supermarket'. The stress is applied by the speaker to highlight their meaning. Is 'I' emphasised to insist that it is 'I' who is going to the supermarket? Is 'supermarket' stressed to insist that it is the supermarket that I am going to, and not another location?

✣ Mutations are inherited from Welsh and its earlier forms. The same is true between Pre-Sindarin (or what Tolkien then referred to as Noldorin) and Sindarin.

-> Welsh: atar evolved into adar 'bird' (lenition of t into a d)

-> Sindarin: atar evolved into adar 'father' (same pattern)

✣ No cases in Sindarin verbs, unlike in Quenya. This means that there is no Nominative, Genitive, Dative or Accusative.

✣ Like in Welsh, again, some plural forms of nouns involve what we call a vowel change. This means that according to a regular pattern, the vowels contained within a noun are not the same between their singular and their plural forms. In Sindarin, the vowel change and suffixes help to mark plurals. As far as I'm aware, the changes are identical in Welsh, so if you wish to use Sindarin in your own work, have a look at the vowel changes rules and you should be able to form your own plurals. Please note that it occurs with both non-final and final syllables.

-> examples:

- adan 'man' -> edain 'men'

- certh 'rune' -> cirth 'runes'

- annon 'gate' -> ennyn 'gates'

- amon 'hill' -> emyn 'hills'

- mellon 'friend' -> mellyn 'friends'

- Dúnadan 'Man of the West' -> Dúnedain (u is not affected)

✣ Suffixes are another way to mark plurals.

-> examples:

- harad 'south' + rim 'multitude' = Haradrim 'Southrons, Men of the South'

- hadhod 'dwarf' + rim 'multitude' = Hadhodrim 'Dwarves (as a race)'

✣ Compounds are common as well.

-> example:

- morne 'darkness, blackness'/morn 'dark, black' + ia 'pit, gulf' = Moria

✽ Questions I asked Dr. Griffith directly and his answers

✣ Q: In your article and in the PowerPoint presentation, you sometimes mark terms with an asterisk first (e.g. *rokko-khēru-rimbe when you discuss the origin of the term 'Rohirrim'). What does this notation refer to?

✣ A: An asterisk before a form means that it is not actually found anywhere, but we assume it must have existed. In this case, *rokko-khēru-rimbe is the form of Rohirrim as it would have been pronounced in Old Sindarin, but we don't actually have the word anywhere in a written text

✣ Q: For Rohirric/Rohanese, we know that the language that Tolkien based it on was Old English and that terms were directly borrowed from it (e.g. grīma 'mask' or þeoden 'lord, prince, king'), or that names and phrases from Beowulf have been peppered in the lore of Rohan (e.g. Éomer is a character mentioned once, and the first line sung by Miranda Otto in the 'Lament for Théodred' is a line from Beowulf as well). Unfortunately, it seems that the sources on the languages are few, but do we know his reasoning or process in tweaking and applying Old English to create Rohirric/Rohanese? Do we know, perhaps, how the grammar differed from Old English?

✣ A: We don't really know anything about the language of the Rohirrim. Tolkien chose Old English as a sort of cipher. What I mean is: the language of Middle Earth is called Westron, and the Rohirrim spoke a very archaic dialect of it. Tolkien represented this by having them use Old English/archaic forms. He talks about this in one of the appendices to The Lord of the Rings, though I don't remember which one.

✣ Q: In your opinion, is it realistic to compose texts in Quenya or Sindarin, considering that we do not really have a cultural context behind them that is fully explicit? By this, I mean that since idioms and certain concepts are intrinsically tied to their cultural context, is it possible to actually use the Elvish languages to compose new texts altogether?

✣ A: It is possible to compose texts in Quenya and Sindarin. People do it. Obviously, some things are simply impossible to know: how would you say 'computer' or 'shopping mall'? And for other things, we cannot really know since only Tolkien really had the 'true understanding' of Elvish languages and cultures necessary for some text production. That said, people do do it. I don't know much about it, though, I'm afraid.

For those who are interested, I have Dr. Griffith's article, the PowerPoint presentation with sources and vocabulary on it, as well as a handout with Noldorin and Old Noldorin. Dr. Griffith also sent me some extra sources, let me know if you want me to send them to you!

If you have questions, I can always try to contact Dr. Griffith again, he is the coordinator of my Middle Welsh course, so I'm bound to bump into him again, and he is genuinely excited to discuss all things Tolkien :)

@konartiste @from-the-coffee-shop-in-edoras @lucifers-legions @emmanuellececchi @hippodameia

#Tolkien#Elvish#Elvish languages#Sindarin#Quenya#Noldorin#linguistics#Middle Earth#Lord of the Rings#LOTR#Tolkien's linguistics#masterpost#reference#lotr ref

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elven word of the day, 117/?

Rusco from Quenya

Meaning “fox”

Source: Parma Eldalamberon

Russa, which means red haired, and where Maedhros’s epessë Russandol originates from, comes from the same root. I enjoy associating Maedhros with foxes 🦊 for this reason

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

how to tell tolkien's languages apart: a beginner's guide

sindarin: looks & sounds like elvish

quenya: chaucer ass elvish (þe olde elvish for the nerds) and there's a lot more weird little things above the letters

khuzdul: if you can pronounce words in a deep voice without laughing then it's khuzdul. also consonants and the vowels have little hats on them

adunaic: even more little hats. also dashes' heaven. also you will laugh if you try to say something out loud

170 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nobody talks about the Shibboleth of Feanor enough.

That is, nobody talks about the Shibboleth of Feanor enough correctly.

Feanor did not decide to pronounce things weird, what he observed was that over the millennia, language gradually changed, and he Did Not Like That. Feanor decided that the language Shouldn’t Ever Change for various reasons, including being the fun police, and being emo about his dead mom, but explicitly, one reason that Feanor wanted everyone to try to speak as close as they could to the same way they did when the first elves awoke is so that there wouldn’t be a language barrier if they ever met the Sindar again.

Now, if we assume that most of the Exiles were around Feanor’s age or younger, and if we assume that Feanor froze his version of Quenya at the point that Miriel died, then we can further assume that everyone who spoke mainstream Quenya did so natively from childhood, learning to speak the language with several of the sound changes that Feanor objected to.

Meanwhile, the younger generations of Feanor’s faction will have grown up speaking the old-fashioned, Feanor approved version of Quenya.

We know, specifically, that one sound change that Feanor personally cared about was the s/th merger, because the th appeared in his mother’s name, Miriel s/therinde. Th is a weird sound, it’s hard to pronounce and is rare across world languages, so it makes sense that Quenya would do away with it. However, Sindarin kept the th. And while Feanor’s Quenya wasn’t the same as Sindarin, both because Feanor froze it at an arbitrary point, and because Sindarin changed probably as much as Quenya did, it stands to reason that it would be closer than the standard version.

Which is all to say, that given the ban and general politics in Beleriand, I find it deeply ironic and hilarious that the Feanorians are the ones who naturally find it easiest to learn Sindarin and have the best Sindarin accents.

Or, TLDR, the sons of Feanor are the only Noldorin leaders who can pronounce “Thingol” correctly, and everyone Hates That.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Excuse me can we please talk about how the Noldor literally say Ave Maria as a goodbye

#lotr#tolkien#quenya#elvish#virgin mary#blessed mother#ave maria#catholic#catholicism#christianity#rosary#silmarillion

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, all I wanted to know what which Quenya words originally had þ instead of s, and instead I stumbled on this thing, and now I need to make it other people's problem.

So I knew a large part of why Feanor was so...twitchy about the þ vs. s thing was because of his mom's name, Miriel þerinde. What I did not know was that, while the verb þer- means "to sew", which means that "þerinde" is "seamstress", there was also a verb ser- before the þer- verb changed.

The original ser- means "to rest". So after the pronunciation shift, "Serinde" could mean either "seamstress" or "she who rests".

Considering that Feanor lost his mom because giving birth to him took so much out of her that she essentially had to permanently rest...I can see why this would be such an incredibly sore point with him.

It's not just about "hey, quit mispronouncing my mom's name", it's about "quit calling my mom 'the one who couldn't hack it and had to go away forever' and use the name that describes her as a craftswoman, you complete troglodytes".

#silmarillion#feanor#miriel therinde#quenya#linguistics my beloved#language rant#there really is always another secret with tolkien languages

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hc that Primitive Quendian (PQ) has a lot of gender neutral terms, and that things like “god” and “king” and “master” in PQ weren’t gendered words the way they are now, so both elleth and ellons would be refered to as “king”, “master”, etc, but as time went on and the language evolved to quenya and sindarin, those words did become gendered, so they were translated as male. The same thing happened with PQ words that mean “damsel” and “slut” and “queen”, which became words associated as female.

And long story short, a lot of stories that were created in PQ were translated to have male heros and female love interests, when in reality the heroes of an epic were pretty diverse across all genders.

In fact, there’s a story called “Swode i Dall” in PQ, which roughly translates to “the swordmaster and the damsel” which is a pretty basic heroic romance about the swordmaster, who always saved the damsel in distress, no matter how many times the damsel got themself into trouble, and it was assumed the swordmaster is an ellon and the damsel is and elleth bc of the respective words becoming more gendered. But in reality the swordmaster in the epic is an elleth, who was specifically based off of Miriel, and the damsel is an Ellon based off of Finwe, and these genders actually make more sense given the context of the story, but it never even crossed many elves’ mind that swordmaster and damsel weren’t gender indications as they were translating the story from PQ into Quenya and Sindarin. The story was actually created bc bby finwe had a massive crush on the strong Miriel and would not go to sleep without the story.

And long story short, there’s a story about Finwe and Miriel in PQ that Feanor has no idea about bc elves got the genders wrong when it was translated.

#everyone was more concerned about describing and naming jobs than they were about gender#primitive quendian#quenya#sindarin#tolkien languages#elvish#pre orome days#feanor#finwe#miriel#give miriel a personality 2023#finwe x miriel#miriel therinde#headcannon obviously#lord of the rings#lotr#lotr elves#silmarillion

43 notes

·

View notes