#Philothee O'Neddy

Text

Oh

Oh heck

looking around for info on Romantics, as I do from time to time, I found one of O’Neddy’s poems from Feu et Flamme , Nécropolis ; I’m not going to past over the whole thing bc it’s long, but this bit:

Sous la tombe muette oh ! comme on dort tranquille !

Sans changer de posture, on peut, dans cet asile,

Des replis du linceul débarrassant sa main,

L’unir aux doigts poudreux du squelette voisin.

seemed Relevant to LM studies. bc loosely translated , it reads as:

“Under the silent tomb, oh! how tranquil one sleeps in this asylum!

Without changing position, one can, folds of the shroud falling from the hand,

Unite it with the powdery fingers of the neighboring skeleton!”

- which of course syncs nicely with this little bit in LM:

“ Oh! would that we were lying side by side in the same grave, hand in hand, and from time to time, in the darkness, gently caressing a finger,—that would suffice for my eternity! “ ( A Heart Under a Stone, aka Marius leaves Cosette a love letter)

I’m definitely not accusing Hugo of “stealing” the idea, or even copying it-- Love in The Tomb was such a common idea for the Gothic Romantic crowd, that would be silly-- it’s just neat to see such a close image in a much-earlier Romantic poem from one of Hugo’s friends.

(the entire poem, and a much better translation, can be found here!)

..OK, I gotta include the epigram O’Neddy starts the poem with, because it’s from Petrus Borel:

Sur la terre on est mal : sous la terre on est bien.

the Dramaaaaaaa

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sir,

The old O'Neddy who, in his quality as a burgave, spends a great deal of his time dreaming in the shadows and in the night, has only recently become aware of the notice you paid to his juvenilia, and which was include in le Boulevard over a month ago already. It is for this reason that he come so late in thanking you warmly.

He succumbs also to the temptation to offer you here a some information and a few observations on his behalf and that of his former brothers, flattering himself that you will not disdain to use them a bit, in the event that your siege (I mean your volume on the romantics) is not already done.

Philotée O'Neddy was, in 1833, the young, the very young nephew and cousin of Mr's Dondey-Dupré father and son. If they printed his little book, they did not edit it. Note this point. Both of them, learned men indeed, detested romanticism, particularly the uncle, who had something of the immortal Gillenormand in his spirit. Fire and Flame did not have an editor. It had to walk its path alone, that is to say that it did not walk it at all. Philothée O'Neddy was very clever and even more awkward. He did not correct himself. Fire and flame only had 300 copies printed.

M. Charles Monselet is correct: Théophile Dondey of Santeny is the same as Philothée O'Neddy. Of Santeny is not a title but only a family name (like Dupré) already used by the father of O'Neddy. The work which was published in the Boulé collection is not called The ring of Salomon. Here is the exact wording of its title: History of an enchanted ring, a novel of chivalry; Paris 1844. There is a preface in verse and an epilogue similarly in verse, ending with a sonnet. The story entitled The Lazarus of love did indeed appear in the ancient Patrie (February 1843, eight pamphlets). In this same year 1843, Théophile Dondey of Santeny wrote theatre critiques, first for la Patrie, then for the Courrier Francais. He thus had the honor, quite precious for him, to become aware of the Burgaves.

Before this, in October 1839, the pamphlet of l'Estafette had published, in two articles, a work of Th.D. of S. titled The Bishop of Saint-Or, episode. This excerpt is taken from an unpublished novel, which remains unpublished, which had for a title Sodom and Solime, which is none other than the novel first announced as Between dog and wolf*, at the end of Fire and flame. Within the prose of the aforementioned Bishop of Saint-Or can be found a long fragment in verse (always verses).

You say, sir, that Petrus Borel was the chief of the group in question. This is not accurate. We were greatly fond of him, and he had his influence. But Gérard de Nerval and Théophile Gautier had just as much, as did Joseph Bouchardy, future dramatist, who was an ardent and enjoyable conversationalist. O'Neddy also had passably peremptory words, and acted as though he were fully in a republic. The synagogue (as you say) held six poets: Gérard de Nerval, Petrus Borel, Théophile Gautier, Alphonse Brot, Augustus Mac-Keat, and Philothée O'Neddy. -- Gérard de Narval had published under the restoration nationalist and Napoleonic poetry, which he did not want anyone to be read, being the first to declare them cliche. He distributed almost nothing of the excellent things he was working on at the time. Alphonse Brot had had printed a collection titled Love songs in 1829. This little book is not to be dismissed, but it lived among us without authority, derived at once from the genres of Parny and of M. Jules of Rességuier. Alphonse himself bragged in his preface that he was neither classical nor romantic. -- We had a few charming verses from Augustus Mac-Keats, but very few in number. -- Before being introduced to the group and discovering the verses and persons of Théophile Gautier and Petrus Borel, O'Neddy had already composed a third of the pieces held within Fire and Flame. The majority, indeed, are dated 1829, 1830, and 1831. It is thus unfair to say that he aped and that he outraged the great rabbis. Furthermore I think that, when comparing his verses with Petrus', it is difficult to not find them very dissimilar. It is not better, but it is other. For example, Petrus Borel is too disdainful of form, and O'Neddy is too curious. -- Similarly, did he imitate Gautier's Albertus, where already the great poet of the Comédie de la Mort announced himself? Again no, and in this case let us an an: alas! He outraged whom? Petrus? Is that really possible? Outraging Petrus! The best one could hope for was equaling him in exaggeration. In this, I confess, O'Neddy did not hesitate. But to say that he was an ape! that is harsh. Call him mad, at the right time, that is acceptable. Sir Don Quixote, the greatest of knights, certainly was! That he had a large store of extravagance and bad taste, nothing is more accurate, but he has the presumption to believe, in this 93 of our literary revolution, that his carmagnole was indeed his own.

You must smile at this nostalgic self-love, and you think perhaps that due to being suceptible to these emotions, my O'Neddy is becoming ungrateful and does not take heed of the great benevolence that at the end of your review you offer to his muse. Stand corrected. He is very grateful. But it seems that he is not yet old enough to have entirely set aside the old man.

I arrive at the most important point, the most delicate, the chief correction. Sir, never was there Bouzingotisme, nor were there Bouzingots. Never did the Jeunes-France of our group (it is only this that we called ourselves and that we must be called) decked ourselves in such a term and in such a qualifier. It is simply a bad joke from the crudities of the bourgeois, like the infamous round danced around the bust of the author of Athalie, to the cry of Racine is an imp! Here is, in truth, the history of the matter. -- One fine day, a few of us took part in a rather lively dinner. On our return, sub nocte per umbram, we were very loud, we sang a less than melodious song, of which the chorus was We have made or We will make bouzingo (note the spelling carefully). In short, we scandalized an entire block of Lutece** and we amply committed the offense of nighttime disorderliness. The watch intervened, disguised as a squadron of policemen and were not nasty. Much worse: three or four Jeunes-Frances were arrested, among others poor Gérard. They were held for a short time at Sainte-Pélagie. From Gérard there is a charming little piece about his captivity. Meanwhile the word bouzingo having made quite an impression, the bourgeois took hold of it, and with their good faith and their usual good taste, took to affirming in the leaflets of order and the holy doctrines, that the young republicans had just taken the name Bouzingots (sic), that they took from it glory, that in this they were correct, that they were thus well named, that they should thus no longer be called otherwise. From there, in the aforementioned leaflets, an unheard of zeal for repeating in all contexts, for six months, the words Bouzingotisme and Bouzingot. At first we laughed about it between ourselves. Théophile Gautier cried, "Those bourgeois donkeys, they don't even know how to write bouzingo! To teach them some spelling, we will have to collectively publish a volume of tales that we will bravely call Tales of the bouzingo!" -- The proposition was widely hailed and we set to work. But the thing never happened, and since then there was no way to go among us but to renounce them, these two wicked words, cacographic product of the bourgrois' heavy magnanimity.

Those who think that we lived in a certain detachment from the popular cause are entirely mistaken. We were, for the most part, republicans. We were familiar with more than one Café Musain. The good Petrus was montagnard, the young O'Neddy, for his part, was girondin. (Here you will not accuse him of outrage.) When Philothée wrote that it was good to avoid the republican fanaticism, he did not mean by that republicanism but conspiracies, riots, attacks, violences. We dreamed of the rule of Art, it is true. It seemed to us that one day Religion must, in its condition of exteriority, be replaced by Aesthetic. But we always wanted other things. The preface of Fire and Flame announces wishes for social revolution. We had among us adherents of Saint-Simonism and Fourierism. So too O'Neddy, in time, was greatly surprised when he saw himself so enthusiastically reprimanded in the Revue encyclopédique for his unfortunate Pandemonium. He thought that he had been sufficiently cautious in his words, taking care to get his characters outrageously drunk before making them guilty of the enormous proposals they delivered.

Do not say, I beg you, Sir, that Petrus Borel was the only one who was sincere. Others were as well. O'Neddy requests for them and for himself. He was, even lost in his Byronic allures and his great attraction for Sir Don Quixote.***

Thank you for the testimony of esteem that you offer to the memory of these good young people. But I offer you one last nitpick! You say that they were ridiculous. Such a word is applicable only to idiots. For madmen, one must content onself with the word laughable. For the love of God! it was our adversaries, the bourgeois and the bankers,**** who were ridiculous!

Forgive me this long epistle. A great many details will no doubt seem less interesting to you than to O'Neddy; he is resigned to the fact that you will rule out the greater part. But do not dismiss everything. Take into consideration, I beg you, my protestation about Bouzingotism. Rid yourself of this villainy. It is impossible that you do not add to your remarkable talent as a writer a scrupulous conscience without which one cannot be a true and worthy critic.

Accept my thanks and all my apologies; accept in spirit a hearty handshake and permit that, in offering it to you, I write this old signature which makes me younger:

Philothée O'Neddy.

[*Translation note: 'entre chien et loup' is a french expression meaning twilight.]

[**Translation note: Lutece is the name of the Gaulish city on which Paris now stands.]

[***Translation note: I am pretty sure that that's what that sentence means, but it's not an especially clear sentence.]

[****Translation note: the actual word is 'chiffreur', which today is apparently translated as 'coder' but which I assume he meant derisively as 'people who work with numbers.' I picked 'banker' as a generalized way to get that concept across.]

#in friendship and in art (but mostly in friendship)#philothee o'neddy#jeunes-france#pilferingapples#will this work this time?#this had better work this time

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Petit Cénacle, Jeunes France and the Bouzingos

Writing this here to start trying to untangle and pin down dates - most of this is Enid Starkey, but I'll update tomorrow with more information and hopefully refine this...need to incorporate information from the O'Neddy letter, as although some of what he said (e.g. the respective roles of Borel, Gautier and Nerval in the early days) is in dispute, he is one of the few members of the group/s who looked back in later years and wrote about their origins. Please kick in additions and corrections as this is fluid at the moment.

c. 1829 – 1831 The Petit Cénacle – junior associate group of the more senior, established Cénacle, the group that met in Charles Nodies rooms.Several - du Seigneur, Bertrand, MacKeat and O'Neddy had medievalised or otherwise changed their names in tribute to Walter Scott or out of general eccentricity.

Members: Joseph Petrus Borel, Jehan du Seigneur (Jean Dusseigneur), Louise Bertrand (Aloysius Bertrand), Auguste Mackeat (Augustus Macquet), Philothée O’Neddy (Théophile Dondey), Eugène Devéria, Théophile Gautier, Ourlioff, Bouchardy, The two brothers nicknamed “Le Gothic” and “Le Christ”, Célestin Nanteuil, Gérard de Nerval

1831: Les Jeunes France – Petrus Borel, Célestin Nanteuil, Bouchardy, Jehan du Seigneur, Philothée O’Neddy, Gérard de Nerval, Théophile Gautier, Eugène Devéria, Boulanger

In 1831 Petrus Borel and followers from the Petit Cénacle migrate from the Latin Quarter to the heights of Rochechouart (present day Boulevard Rochechouart) and rented a large room at the corner of the Rue d’Auvergne. The group soon changed is name to Les Jeunes France. Their rowdy behaviour caused their landlord to give them notice and they moved to La Rue d’Enfer. For a time they continue to attend Nodier’s Sunday literary evenings at the Bibliotheque de L’Arsenal, but they scandalise the more respectable members (with, for example, their outré dress) who protest to Nodier, and they cease to attend.

Late c.1831- 1833: Bouzingos

The group’s name evolved into the Bouzingos – origins of the name somewhat in dispute, but probably derived from “bousin” meaning noise. One story runs that it was originally a name of contempt bestowed on them by those who heard them singing a song with the chorus “Nous allons faire du bouzingo, du bouzingo, du bouzingo”, the group takes it up as a title and they achieve some literary notoriety – in Figaro, there were seven articles devoted to the Jeunes France between August and October 1831, and between January and June 1832 twenty articles and frequent allusions to the Bouzingos.The group breaks up not long after the 1833 publication of O'Neddy's Feu et Flamme and Borel's Champavert of the same year.

Members: Similar to the Jeunes France; Arsène Houssaye also noted as part of the group (Houssaye was also a Dandy – “literary Dandies” formed a separate circle)

#le petit cenacle#jeunes france#bouzingos#philothee o'neddy#petrus borel#Theophile Gautier#Gerard de Nerval#jehan du seigneur#aloysius bertrand#eugene devaria

28 notes

·

View notes

Link

#linkspost#Philothee O'Neddy#Four People and a Shoelace#it is. Very Earnest Young Romantic poetry#oh dear XD

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

It has been observed that the ideal of amour is far more inaccessible to the brushes of human expression than the ideal of dolor; and that impotence is no less the share of geniuses of the first order than secondary minds. Dante and Milton, so sublime with force and color when they paint the terrors and the tortures of the Inferno, show themselves to be feeble and dull when they try to paint the splendors and delights of paradise. (O’Neddy, The Enchanted Ring)

“...look we all tapped out of the Paradiso verses, right? it wasn’t just me?”

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh, it is with my forehead in the dust that I protest my reverence, my respect and my veneration for (marriage)! On approaching its region I am subject to the sacred terror to which people were subject in antiquity as they approached the vicinity of the lair of Trophonius! ...Marriage! but every thinker, every reasoner, ought to adhere to it! Marriage, God’s truth, is the vertebral column of the social body. It is more than a holy thing, it is a necessary thing, and it has an importance equal to the law of recruitment to military discipline, to the magistracy, to the gendarmerie, to the National Guard. -- Philothée O’Neddy, The Enchanted Ring, a Romance of Chivalry (1841)

..I was not expecting this story to subvert its entire form halfway through? at least not so blatantly?? I really thought we were just gonna surf along on undercurrents of Commentary but no, “I know writers who use subtext and they’re all cowards” is really just the banner for the whole crew huh

#Four People and a Shoelace#Philothee O'Neddy#this is magnificent and changes the entire story#love it when the lads get Ironical#The Enchanted Ring

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is my fave picture of O’Neddy I’ve ever come across, but this is the only size I’ve ever seen it at, and I can’t even tell who drew it! If anyone has a better idea of where it’s from, let me know?

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

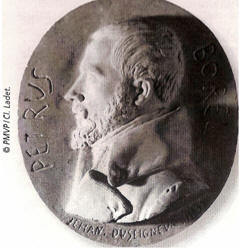

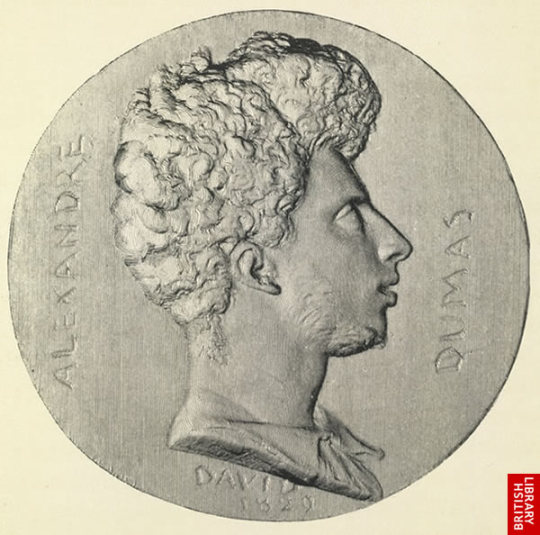

Medallions by Jehan du Seigneur! (And one from David--that’s Dumas) Dated roughly from 1829 (Dumas) to ~1831 Top row:

Gerard de Nerval (then still going by Labrunie) and Petrus Borel

Second row:

Theophile Gautier, Philothee O’Neddy (I’ve only been able to find the etching of this one! if anyone has a photo of the medallion itself, please let me know!)

Bottom row: Alexandre Dumas

I love these things-- for most of the crew here, these are the only portraits I can find for them from those very early years when they were still fairly obscure and photography wasn’t really a possibility yet (exception: Dumas was already pretty famous at this point, and has a good few sketches, caricatures etc). Images of Gautier before he grew his hair out and O’Neddy without his beard are pretty hard to find!

I’ll add more to this post if I find any!

#Four People and a Shoelace#Romanticism#Alexandre Dumas#Gerard de Nerval#Petrus Borel#Theophile Gautier#Philothee O'Neddy#Jehan du Seigneur

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Que je l'aime ce nom, saint dans tous les langages,

Ce nom terrible, écrit sur le char des orages,

Ce nom, beau de puissance et d'immortalité,

Qui fait pleurer les rois dans leur alcove immonde,

Que nous verrons un jour le seul culte du monde,

Ce nom de bronze, Liberté !...

-Philothee O’Neddy

- À Monsieur mon très-cher frère Théophile Dondey, offert du meilleur de mon cœur.- dedication from Petrus Borel in O’Neddy/Dondey’s copy of Madame Putiphar

Theophile Dondey/Philothee O’Neddy was one of the more overtly republican and activist of the Jeunes France. His poetry was mostly in the frenetic camp. despite his open and lifelong admiration for more formal or moderate writers like Hugo and Gautier.

O’Neddy had to give up being fully active in both art and politics in 1832, when his father, a minor civil servant, died in the cholera epidemic, one month before he and his family would have been eligible for a pension. Dondey, then all of 21, was left to support his mother and infant sister. He fell out of the spotlight (and out of public consideration as a possible future Great Writer), but he stayed involved on the periphery of the artistic movement, writing reviews and small essays (and several poems that wouldn’t be published until after his death).

Like most of the Jeunes France, he also stayed close to his old Romantic friends,especially his fellow republican Petrus Borel, and built up a considerable archive of the group’s publications and correspondence (unfortunately sold off after his death).

Sources:

top photo: Engraving of a medallion by Jehan du Seigneur

bottom photo: photo of O’Neddy, photographer unknown

Resurrecting the Bouzingo

Lekti-Ecriture

Letter to Asselineau

letter in French

A History of Romanticism, by Theophile Gautier

The Lycanthrope, Enid Starkie

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

A translation,with footnotes, of one of O’Neddy’s poems!

5 notes

·

View notes