#Outset Book Reviews

Text

2024 Book Review #13 – Victory City by Salman Rushdie

One of my goals for the year is to read more proper literature (here defined as fiction I can mention reading to my mother without getting judged for it). I’ve never read anything of Rushdie’s before, but I did remember his name in the news recently due to the whole attempted-murder thing and, happily, my library actually had a copy of his newest work. So, picked this up and read it sight unseen!

The book follows one Pampa Kampana – a nine-year-old girl who, in the 14th century, witnesses her city destroyed, and her mother burning herself alive. She is then inhabited and blessed by a goddess, blessed/cursed with a lifespan measured in centuries and the destiny of raising an empire up and seeing it fall before she dies.

The narrative is framed as a modern adaptation/summary of the epic poem recounting her life Pampa completes before finally dying, finally discovered and translated after being forgotten in the ruins of te imperial capital for centuries. The story is largely a story of this miraculous, semi-utopian empire, as told Pampa’s eyes (and with a lengthy digression during the years she spends in exile).

This is a story that exists somewhere in the muddy middle ground between historical low fantasy and magical realism – it’s in some sense an alternate history of the Vijayanagara Empire, and replete with historical trivia and references, but is quite clear from the outset that accuracy is not really something the book cares about. Instead, the book’s Vijayanagara – always written as Bisnaga, as it was translated by a historical Portuguese chronicler whose also a minor character in the story, to prevent confusion – is basically allegory and morality tale with a light coating of history for flavour.

Not that I can really begrudge Rushdie for his strident politics (as far as I can tell I basically agree with him on all of it), but this really does feel like one of those old fantastical utopias, or a political treatise that gets past the censors by pretending to be the history of a foreign country, more than it does a novel. Which could definitely work! But in this case really didn’t, at least for me. There’s enough time spent on characterization and character drama to eat up pages, but not enough for it to ever feel like they’re people and not just marionettes acting out a show. I suppose the best way to get across the reading experience is that I was reading a proper 500 page history book at the same time as I read this, and this felt like the bigger slog by far.

Though part of that might just be disappointed expectations that I really had no right to have in the first place? As I said, I had Rushdie slotted in my head as a literary author, but really I don’t know nearly enough about him or his work to justify that. So I came to this expecting to be at least a bit wowed and bedazzled by the artistry and beautiful prose on display – and like, eh? Not bad, to be sure, the narrative voice and the framing device are both fun and fairly well done. But having read it there’s really not a single passage or sequence I can say has stuck with me.

The comparison that comes to mind is Kalpa Imperial by Angélica Gorodischer, which is also a book-length epic history of a fantastical empire that never was which laughs at all conventional wisdom about pacing, characterization and plot (and which also has been shelved as magical realism for what are basically reasons genre snobbery imo). It’s been a few years since I read it, but from what I recall that agreed with me far more. Maybe just because it abandoned the conceit of a single protagonist and family melodrama entirely, or maybe because it had a bit more subtle in its social commentary (or maybe it was just better written on a sentence-to-sentence level).

Though I should say, there’s every possibility I’m being a bit harsher on this than it entirely deserves – it’s an entirely competent book! The politics are blatant but like a) they’re politics I agree with and b) they’re nowhere near the most blatant or forced-feeling inclusion of progressive politics in fiction I’ve seen recently. However, this is also a piece of writing that’s among other things very clearly and directly about how important and sublime and world-changing the art of writing is. Which is like a movie about making it in showbuisness, or a musical about how great singing is. Automatic deduction of a full letter grade.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Andrew Doyle

Published: Apr 18, 2024

“Why do you think the giraffe has a long neck?” says the naturalist Philip Henry Gosse to his son Edmund while he tucks him up into bed. “Does it have a long neck so that it can eat the leaves at the top of the tree? Or does it eat the leaves at the top of the tree because it has a long neck?”

“Does it matter?” says Edmund.

“A great deal, my son.”

This exchange is taken from Dennis Potter’s wonderful television play Where Adam Stood (1976), a loose adaptation of Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son (1907). Gosse’s book must rank among the very best of autobiographies. It is his account of being raised by his father Philip, one of Darwin’s close contemporaries, a man whose faith in the Bible was so fervent that the revelations of natural selection almost destroyed him.

The question about the giraffes is Potter’s invention, but it adroitly captures the profound inner struggle of this scientist who had devoted his life to a belief-system that was suddenly falling apart. It wasn’t just a matter of changing his mind as new evidence emerged, because the proposition that the earth’s age could be numbered in the billions rather than the thousands was not something that his faith could accommodate. The stumbling block was the Bible, a point that Edmund is quick to acknowledge in his book:

“My Father’s attitude towards the theory of natural selection was critical in his career, and oddly enough, it exercised an immense influence on my own experience as a child. Let it be admitted at once, mournful as the admission is, that every instinct in his intelligence went out at first to greet the new light. It had hardly done so, when a recollection of the opening chapter of Genesis checked it at the outset. He consulted with Carpenter, a great investigator, but one who was fully as incapable as himself of remodelling his ideas with regard to the old, accepted hypotheses. They both determined, on various grounds, to have nothing to do with the terrible theory, but to hold steadily to the law of the fixity of species.”

Philip Gosse had an instinct for scientific enquiry, but the new discoveries simply could not be reconciled with his holy text. His whole being was invested in the Biblical truth, and to cast that in doubt would be to undermine the crux of his being. To admit that he might have been wrong, in this particular instance, would be a form of spiritual death.

Both Gosse’s memoir and Potter’s dramatisation grapple with what Peter Boghossian and James Lindsay (in their book How to Have Impossible Conversations) call an “identity quake”, the “emotional reaction that follows from having one’s core values disrupted”. Their point is that when arguing with those who see the world in an entirely different way, we must be sensitive to the ways in which certain ideas constitute an aspect of our sense of self. In such circumstances, to dispense with a cherished viewpoint can be as traumatic as losing a limb.

The concept of identity quakes helps us to understand the extreme political tribalism of our times. It isn’t simply that the left disagrees with the right, but that to be “left-wing” has become integral to self-conceptualisation. How often have we seen “#FBPE” or “anti-Tory” in social media bios? These aren’t simply political affiliations; they are defining aspects of these people’s lives. This is also why so many online disputes seem to be untethered from reason; many are following a set of rules established by their “side”, not thinking for themselves. When it comes to fealty to the cause, truth becomes irrelevant. We are no longer dealing with disputants in an argument, but individuals who occupy entirely different epistemological frameworks.

Since the publication of the Cass Review, we have seen countless examples of this kind of phenomena. Even faced with the evidence that “gender-affirming” care is unsafe for children, those whose identity has been cultivated in the gender wars will find it almost impossible to accept the truth. Trans rights activists have insisted that “gender identity” is a reality, and their “allies” have been the most strident of all on this point. As an essentially supernatural belief, it should come as no surprise that it has been insisted on with such vigour, and that those who have attempted to challenge this view have been bullied and demonised as heretics.

Consider the reaction from Novara Media, a left-wing independent media company, which once published some tips on how to deceive a doctor into prescribing cross-sex hormones. Novara has claimed that “within hours of publication” the Cass Review had been “torn to shreds”. Like all ideologues, they are invested in a creed, and it just so happens that the conviction that “gender identity” is innate and fixed (and simultaneously infinitely fluid) has become a firm dogma of the identity-obsessed intersectional cult.

Identity quakes will be all the more seismic within a movement whose members have elevated “identity” itself to hallowed status. When tax expert Maya Forstater sued her former employers for discrimination due to her gender-critical beliefs in 2019, one of the company’s representatives, Luke Easley, made a revealing declaration during the hearing. “Identity is reality,” he said, “without identity there’s just a corpse”.

This sentiment encapsulates the kind of magical thinking that lies at the core of the creed. So while it becomes increasingly obvious that gender identity ideology is a reactionary force that represents a direct threat to the rights of women and gay people, there will be many who simply will not be able to admit it. In Easley’s terms, if their entire identity is based on a lie, only “a corpse” remains. From this perspective, to abandon one’s worldview is tantamount to suicide.

This determination to hold fast to one’s views, even when the evidence mounts up against them, is known as “belief perseverance”. It is a natural form of psychological self-defence. After all, there is a lot at stake for those who have supported and enabled the Tavistock Clinic and groups like Mermaids and Stonewall. Many of the cheerleaders have encouraged the transitioning of children, sometimes their own. What we have known for years has now been confirmed: many of these young people will have been autistic, or will have simply grown up to be gay. For people to admit that they supported the sterilisation of some of the most vulnerable in society would be to face a terrible reality.

This idea was summarised in parliament on Monday by Victoria Atkins, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. Addressing Labour MP Wes Streeting, she said:

“I welcome all those who have changed their minds about this critical issue. In order to move forward and get on with the vital work that Dr Cass recommends, we need more people to face up to the truth, no matter how uncomfortable that makes them feel. I hope the honourable gentleman has the humility to understand that the ideology that he and his colleagues espoused was part of the problem. He talked about the culture and the toxicity of the debate. Does he understand the hurt that he caused to people when he told them to ‘just get over it’? Does he know that when he and his friends on the left spent the last decade crying ‘culture wars’ when legitimate concerns were raised created an atmosphere of intimidation, with the impact on the workforce that he rightly described?”

youtube

It remains to be seen whether those politicians who failed to grapple with the implications of gender identity ideology, and who mindlessly accepted the misleading rhetoric of Stonewall and its allies, will have the humility to admit that they were wrong. Many culpable celebrities have been choosing to remain silent in recent days, while others have opted for outright denial. On the question of puberty blockers and their harm to children, television presenter Kirstie Allsop has made the remarkable claim that “it is, and always has been possible to debate these things and those saying there was no debate are wrong”. The concept of “no debate” was official Stonewall policy for many years, and has been a mantra for many within the trans activist movement. To suggest that there have been no attempts to stifle discussion on this subject can only be ignorance, mendacity or a remarkably acute form of amnesia.

Of course, the stakes could hardly be higher. We are dealing with complacency and ideological capture that had resulted in the sterilisation and castration of healthy young people. It is, without a doubt, one of the biggest medical scandals of our time. It is entirely understandable that those who have supported such terrible actions would enter a state of denial. And so we must also be sensitive to those who are now strong enough to admit that they were mistaken.

But we also need to prepare ourselves for the inevitable doubling down. There are those whose psyche cannot withstand the kind of identity quake that Philip Henry Gosse once suffered. His solution was to write a book explaining why God had left evidence of natural selection. It was called Omphalos (1857) – the Greek word for “navel” – and his thesis was that since Adam had no mother, his navel was merely an addition to generate the illusion of past that did not exist. The fossils that were being discovered in the ground were therefore no different than the rings in the first trees in the Garden of Eden. They weren’t evidence of age, but rather part of God’s poetical vision.

Some of the revisionism and excuses from gender ideologues are likely to be even more elaborate. They have invested too much in their fantasies to give up without a fight.

==

As gender identity ideology falls apart, we need to pay attention to who is working to fix the mistakes they made, who is doubling down, and who is remaining silent.

#Andrew Doyle#revisionism#gender ideology#gender identity ideology#queer theory#Cass report#Cass review#intersectional feminism#gender cult#medical scandal#medical mutilation#medical corruption#ideological capture#ideological corruption#religion is a mental illness

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpts from Edward Said's The Essential Terrorist, a review of the 1986 book Terrorism: How the West Can Win by Benjamin Netanyahu

This brings us to the book at hand, Terrorism: How the West Can Win, edited and with commentary, weedlike in its proliferation, by Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli ambassador to the United Nations. A compilation of essays by forty or so of the usual suspects–George Shultz, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Lord Chalfont, Claire Sterling, Arthur Goldberg, Midge Decter, Paul Johnson, Edwin Meese 3d, Jean-Francois Revel, Jack Kemp, Paul Laxalt, Leszek Kolakowski, etc.–Terrorism is the record of a conference held two years ago at the Jonathan Institute in Washington, Jonathan Netanyahu being Benjamin’s brother, the only Israeli casualty of the famous raid on Entebbe in 1976. (It is worth noting that victims of “terrorism” like Netanyahu and Leon Klinghoffer get institutes and foundations named for them, to say nothing of enormous press attention, whereas Arabs, Moslems and other nonwhites who die “collaterally” just die, uncounted, unmourned, unacknowledged by “us.”)

[...]

In fact, Terrorism: How the West Can Win is a book about contemporary American policy on only one level. It is equally a book about contemporary Israel, as represented by its most unyielding and unattractive voices. An attentive reader will surely be alerted to the book’s agenda from the outset, when Netanyahu, an obsessive if there ever was one, asserts that modern terrorism emanates from “two movements that have assumed international prominence in the second half of the twentieth century, communist totalitarianism and Islamic (and Arab) radicalism.” Later this is interpreted to mean, essentially, the K.G.B. and the Palestine Liberation Organization, the former much less than the latter, which Netanyahu connects with all nonwhite, non-European anticolonial movements, whose barbarism is in stark contrast to the nobility and purity of the Judeo-Christian freedom fighters he supports.

Unlike the wimps who have merely condemned terrorism without defining it, Netanyahu bravely ventures a definition: “terrorism” he says, “is the deliberate and systematic murder, maiming, and menacing of the innocent to inspire fear for political purposes.” But this powerful philosophic formulation is as flawed as all the other definitions, not only because it is vague about exceptions and limits but because its application and interpretation in Netanyahu’s book depend a priori on a single axiom: “we’ are never terrorists; it’s the Moslems, Arabs and Communists who are.

[...]

Certainly Israeli violence against Palestinians has always been incomparably greater in scale and damage. But the tragically fixated attitude toward ‘armed struggle’ conducted from exile and the relative neglect of mass political action and organization inside Palestine exposed the Palestinian movement, by the early 1970s, to a far superior Israeli military and propaganda system, which magnified Palestinian violence out of proportion to the reality. By the end of the decade, Israel had co-opted US policy, cynically exploited Jewish fears of another Holocaust, and stirred up latent Judeo-Christian sentiments against Islam.

[...]

For the main thing is to isolate your enemy from time, from causality, from prior action, and thereby to portray him or her as ontologically and gratuitously interested in wreaking havoc for its own sake. Thus if you can show that Libyans, Moslems, Palestinians and Arabs, generally speaking, have no reality except that which tautologically confirms their terrorist essence as Libyans, Moslems, Palestinians and Arabs, you can go on to attack them and their ‘terrorist’ states generally, and avoid all questions about your own behavior or about your share in their present fate.”

#the essential terrorist#edward said#edward w. said#benjamin netanyahu#terrorism#terrorism how the west can win#israel#i read this on blaming the victims earlier this year and idk that this has been circulated on tumblr much. glad it's in The Nation website!#zionism#post

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

For the beautiful interior graphite pieces by Brenda Lyons for the GryphIns series, the plan was to keep them as a perk for buying copies of the books. As more and more fans are experiencing the series on audio, I've been a little happier to show them on social media, just to make sure the audio listeners get to see them, too.

The first piece for Eyrie was a deliberate choice: Reeve Brevin, the antagonist, in all her snake-themed peacock glory. While the series has gryphons that are more traditional (Zeph matches the traditional Egyptian gryphon pretty well as a hawk, Cherine matches the traditional Greek gryphon pretty well as a golden eagle), I'd noticed that there were some fans who wanted gryphons to be specifically a North American bald eagle + lion gryphon. While I love all gryphons, I didn't want someone to pick up this story and be disappointed. The choice to go with a green peafowl was intentional, especially as Zeph was on the cover, to let readers know from the outset that you were going to get interesting gryphons in interesting locations with this series.

The interior art pieces were set in the front instead of inside the text so if you picked up the book, you'd see Brevin and Hatzel (another non-traditional gryphon, saber-toothed tiger and the extinct Haast's eagle) first. If you wanted traditional (or bald eagle?) gryphons only, you knew this was a series to skip. But if the idea of interesting gryphons captivated your imagination, you were in.

Later editions would move the interior art pieces into the, well, interior of the novel, near where you meet each of the characters. Zeph and Kia, as the protagonists of Eyrie, also received interior art pieces. The reasoning there was that, once a few books were out, it was clear the series really lived up to its "interesting gryphons in interesting locations" mantra. Zeph may look boring (I'd argue he's interesting and pretty) on Eyrie's cover, but the next few books gave us snowy owls, shrikes, Peruvian diving petrels, European starlings, hooded pitohui, hoopoe birds, snow leopards, great blue herons, and white-tailed kites front and center.

Here at the beginning, however, in March of 2019, we wanted to set an expectation. And while Hatzel did some of that on her own, the choice of Brevin specifically let us show off the harnesses and jewelry the opinici in the series wear. It set an expectation: you won't get gryphons with laser guns, but there's some kind of society here.

I've always been grateful that we met Brenda Lyons. My husband came across her work at local conventions, and came home with one of her pine phoenix pieces for the office. She was working on a cover for another of my books when we all got to talking, and when you have three gryphon fans together, the topic often turns to The Black Gryphon by Mercedes Lackey and Larry Dixon. And how much we all loved Larry's interior art pieces for the series, how they shaped many artists and authors today. Though the first review copies of Eyrie had gone out, there was a moment where we realized there was just enough time before the print files were finalized to do interior art. And the rest is history.

(The choice of Brevin also hinted at the origins of the gryphons and opinici in having a female character with male bird plumage. Growing up with peacocks and peahens guarding the nearby orange groves, I do know the difference between peafowl. But in addition to the nature angle, it foreshadowed the queerness of the characters. With Pridelord's release, it's probably the series with the most trans gryphons in it.)

#Brenda Lyons#gryphon#gryphins#gryphon insurrection#fantasy#griffin#griffon#gryfon#creature fantasy#Reeve Brevin#Eyrie#green peafowl#peacock gryphon#peaphon#opinicus

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

After the war, as a student first at Brooklyn College and then at Columbia, Hilberg was quickly drawn to the academic study of the fate he had escaped in Europe but that many of his relatives had not. "Briefly I weighed the possibility of writing a dissertation about an aspect of war crimes, and then I woke up," he explained in his autobiography. "It was the evidence that I wanted. My subject would be the destruction of the European Jews." He was soon spending long hours in a torpedo factory in Virginia that had been transformed into a repository for countless boxes of captured Nazi archives. Hilberg’s decision to study this material was not considered a professionally prudent one at the time, which may seem odd in the current era of Holocaust movies and proliferating Holocaust studies departments. But in the late 1940s and ’50s, the genocide of the Jews was a subject ignored in academic circles. History books of the era focused on the cult of Hitler and the Nazi terror but generally did not identify the slaughter of the Jews as a central part of the story of World War II. In the United States, the first college-level course dedicated to the subject of the Holocaust was taught in 1974–by Raul Hilberg. More than twenty years earlier, when Franz Neumann, Hilberg’s adviser at Columbia, learned of his dissertation topic, he quipped, "It’s your funeral."

Hilberg’s study opens with a bold statement: "Lest one be misled by the word ‘Jews’ in the title, let it be pointed out that this is not a book about the Jews. It is a book about the people who destroyed the Jews." Hilberg toiled for nearly a decade in the archives of the Nuremberg trials and other collections of recovered German documents. During his last lecture, which he delivered in Vermont just a few months before his death, he recalled the void that engulfed him at the outset of his research. "I was transported into a world for which I was totally unprepared," he explained in his dry, austere manner. "I would read a document, but I would not understand what it meant. The context had to be built record by record."

In Hilberg’s telling, the murder of the Jews was not a product simply of Hitler’s anti-Semitic rage (as Dawidowicz would later argue), nor was it preordained the moment the Nazi Party coalesced or even by the terror of Kristallnacht. "The destruction of the Jews was an administrative process, and the annihilation of Jewry required the implementation of systematic administrative measures in successive steps." Hilberg presented a staggering picture of the bureaucratic machinery of extermination, which developed slowly over time and inundated every sector of German society–not just the Einsatzgruppen and the SS but also the finance ministry, foreign office and railways; everyone knew what was happening, and everyone cooperated.

Hilberg defended his dissertation in 1955 and submitted it to prominent publishing houses. It was roundly rejected until 1961, when a young press in Chicago, Quadrangle Books, decided to publish the work, printing it in double columns on cheap paper. From there, the massive tome began quietly and slowly to win over admirers. In a glowing review in Commentary, the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote that Hilberg’s book was "not yet another chronicle of horrors. It is a careful, analytic, three-dimensional study of a social and political experience unique in history: an experience which no one could believe possible till it happened and whose real significance still bewilders us." Michael Marrus, the foremost historiographer of the Holocaust, says that it is now generally agreed that before Hilberg "there was not a subject. No panoramic, European-wide sense of what had happened. That’s what Hilberg provided."

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

ftr this is my current list of books I started and plan to finish

the adventures of anima al-sirafi (fun, and I enjoyed city of brass too despite some juvenile writing choices)

ancillary justice (👀)

annihilation (BIO SCIFI!!! the writing is so beautiful)

entangled life (fungi 🥰)

go tell it on the mountain (just gorgeous and so powerful)

kitchen (I learned about this one from a FANFICTION don't look at me. it's good)

mask of mirrors (one of the few ya-esque action novels I still enjoy. the social politics and con artistry and action is pretty fun)

mistborn (I've wanted to read brando sando forever. his ending of wot may have been a bit off-key but he's undeniably a giant in the high fantasy world)

see what you made me do (really insightful!)

snow crash (honestly this one is a bit racist, or at least tone-deaf, but the plot is really interesting and it's wild to see a view of the future from the 90s that's fairly accurate in a lot of ways)

books I have yet to start

babel

beloved

the bluest eye

the buried giant

dead collections

the fire next time

gathering moss

a gentleman in moscow

giovanni's room

the goblin emperor

horse

I'm glad my mom died

land of milk and honey

lolita

a memory called empire

monarchs of the sea (octopus book)

my year of rest and relaxation (I've heard mixed reviews but like. why not)

other minds (other octopus book)

our share of night

pachinko

the parted earth

the tiger's wife

the translator's invisibility

uprooted and spinning silver (tbh I don't remember why people hate naomi novak and these look kind of neat)

the water dancer

the woman in me

year of wonders

books I tried but couldn't get into

fourth wing (looked a bit silly from the outset but the writing was SO juvenile I was like no by the first page)

jasmine throne (the opening scene just was not engaging imo)

jonathan strange and mr. norrell (weirdly boring and the austen pastiche fells a little flat)

way of kings (brando sando got so classic he went full predictable chosen-one beginning and it was really boring)

kindle keeps reccomending me paperback thrillers and romances, which are among my least favorite genres. I can see why people like doing this one goodreads or storygraph but I don't know anyone on there so this is better bc I can actually discuss with people I know. man I hope I keep up this momentum to actually finish half of these bc this is a lot 😭 I have so much catching up to do

#cor.txt#my general rule is that if I'm not interested in the sample chapters then I don't continue#there are so many books I want to stick with the ones I already think I'll like#cor reads

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On page 419 of Death’s End and I am going to GNAW ON THE WALLS PRETTY SOON because this series has enthralled me. I’m not sure what I expected when I picked up the book and honestly I’m not sure knowing ahead of time would have made much difference--I’m reading reviews for the early books, trying to gather my thoughts together, because they feel like they’re pinging off in a dozen different directions at once, and thinking about how I probably would have felt like this was overhyped, either before I read it or once I’d read it.

Because what really gets me about this series is the absolutely relentless pacing of it and how it feels to experience that. From the outset, if you’d explained the structure of the story to me, as I’ve wanted to several times when talking about the book, because I feel I should give an accurate view of what it’s like, I think I would have been less than enthused. It’s incredibly brisk, the characters aren’t ones that really lend themselves towards fandom-type Blorbos (though, I do love several of them), and it’s about weaving together culture, science, and the fundamental questions about what drives sentient people.

With each scene, the story keeps moving forward, there’s always a new puzzle to tease out, a new question about what motivates an alien race that we may or may not think similarly to, that humanity is stepping onto a galactic playing field that’s been going on for longer than they know, and the nature of the universe. I had no idea what to expect when I read the premise of the books, other than that it was reasonably hard scifi, which it is, but at a more fundamental level, I think it’s mostly about what people do when they discover new things and what that means in regards to your relationships with other peoples.

The way the story is written, almost like a series of puzzles to solve, then a bombshell is dropped, and you have a new series of puzzles to figure out, is an absolute rush to read, it’s addictive and more than one night I stayed up just to read one more chapter, because the reveal moments work so damn well each time. The answers the story gives, even the way it leads to more questions, satisfied me every single time. Especially because the answers weren’t always nice ones, so I never knew whether the characters would figure their way out of this one or if they would be trapped in a corner and have to face a terrible cost.

This is very much a story about humans facing what seems like an impossible mountain to climb and the messy, shell-shocked feeling of how all of that plays out.

Is this a perfect series? No, I can see why some people warned me about parts of it, especially that there are some moments of side-eye-worthy sexism, but what the story delivers on is fantastic and it’s made me genuinely excited to read more genre stories again, because I fell in love with that sense of exploration, of discovery of what’s around the next corner that’s wildly imaginitive, that a story can grip me in the thrall of desperately wanting to know where all of this is going.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

On 6 July 1860, a British consul by the name of George Whittingham Caine arrived at the nondescript port of Swatow, today’s modern Shantou. He “disembarked from a warship to the cacophony of a seven-gun salute” and, following the obligatory hoisting of the Union Jack [...], “triumphantly declared the treaty port of Chaozhou ‘open’.” Yet unlike other treaty ports scattered along the maritime fringes of the tottering Qing empire, the British found themselves from the outset outflanked by established Chaozhouese (otherwise known as Chiuchow or Teochew) trading communities and failed to gain a foothold in the profitable local commodity trade in rice, sugar, beancake [...].

[T]he Chaozhouese emerged from a[n] [...] ungovernable corner of Guangdong and joined the ranks of the Fujianese and Cantonese as major players in commerce and commodity production, not only along China’s southeastern littoral but across the different territories washed by the South China Sea. The story of the rise of maritime Chaozhou is set against the backdrop of state attempts to subdue and pacify [the region] [...], the emergence of colonial states in Southeast Asia, and the booms and busts of the commodity trade. [...]

[F]rom 1869 to 1948, around six million laborers departed from the port of Swatow and fanned out across the Nanyang (or “Southern Ocean”) [...]. They worked in Chaozhouese-owned gambier, pepper, rice, sugar, rubber, and fruit plantations, toiled in the gold mines of West Borneo, and served as sailors in the intra-Asian junk trade. These overseas sojourners provided a steady trickle of remittances and in the process transformed the local economy [...] [and] brought Siam, Malaya, Borneo, French Indochina, Hong Kong and Shanghai within the orbit of maritime Chaozhou.

---

The story of the heyday of maritime Chaozhou [...] is bookended by two defining moments; the ascent, following the collapse of Ayutthaya in 1767, of the half-Chaozhouese king of Siam, Taksin, and the catastrophic collapse of the global economy in the 1930s. [...] Ming and Qing [authorities] attempt[ed] to subjugate China’s unruly southeastern littoral. A series of interdictions and measures, ranging from the forced depopulation of complete coastal areas in the second half of the seventeenth century to Fang Yao’s [...] “pacification campaigns” in the 1860s, wreaked havoc but also buttressed anti-dynastic sentiments and reinforced Chaozhou’s maritime orientation. [...] These [...] campaigns triggered [...] migration of several generations of Chaozhouese men [... ]. Singapore's authorities were overwhelmed [...] [and this] worked as a catalyst for the British colonial project in the Straits Settlements. [...]

"Mexican dollars, Hong Kong dollars, French Indochinese piasters, Philippine pesos, Straits dollars and Japanese yen inundated local markets” and sustained a remittance-dependent Chaozhou economy that was always oriented towards the Nanyang and [...] removed from Beijing.

---

But the steady influx of foreign-earned capital also had its shadows. Remittances exacerbated social divides [...]. Furthermore, the success stories of some protagonists, [...] whose fabulous wealth derived from their near-monopoly on gutta-percha during Malaya’s rubber boom, are matched by uncountable, and often irretrievable, stories of suffering and hardship.

Thousands of migrants embarked penniless as “credit ticket coolies” and were shipped under trying conditions to far-flung places where they then toiled for months to earn their passage fare back. [...]

Its leading merchants and brotherhoods competed as well as cooperated with colonial actors across Southeast Asia [...] and Chaozhou-controlled business ventures were crucial to the evolution of industrial capitalism both at home and overseas.

---

Text by: Yorim Spoelder. '"Distant Shores: Colonial Encounters on China's Maritime Frontier" by Melissa Macauley'. Asian Review of Books. 5 October 2021. [A book review published online in the Non-Fiction section of Asian Review of Books. Some paragraph breaks/contractions in this post added by me.]

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks to Sourcebooks Fire for providing me with an ARC in exchange for an honest review

✩🃏🕰️Review:

“What Happens After Midnight” tore me apart and then put me right back together again!

I was invested in Lily and Tag at the very outset and held on to hope that they would be able to mend their relationship by the novel’s end. Walther’s newest release is written solely from Lily Hopper’s point-of-view as she embarks on one last adventure with the senior class jester, who just so happens to be her ex-boyfriend Tag, in stealing the class yearbooks. As one of the jester’s fools, Lily works with Tag to leave clues hinting at the yearbooks’ whereabouts around campus for the senior class president to find. Visiting certain locations on campus trigger memories about her past relationship with Tag, shedding light on the whirlwind romance they once had and what led to their eventual split. Lily vows that once the night is over, she will put her past with Tag behind her. The more time she spends with him, however, the harder she falls for him all over again. Little does she know that Tag orchestrated the whole night in an attempt to win her back.

Walther creates an immersive experience by ensuring that her fictional boarding school is representative of real schools by creating diverse characters that are a part of the student population, which I greatly admired. Walther spreads awareness about diabetes through Tag, who has a type 1 diagnosis, and gives her readers opportunities to see themselves in her characters and their different cultural backgrounds and sexual orientations.

Like her debut novel, “What Happens After Midnight” is formatted in a unique way. Each section of the book is separated by the different clues Tag and Lily hide as part of their senior prank. Walther also sprinkles in Taylor Swift references throughout the book, further drawing me in and contributing to its playful atmosphere.

➤ 5 stars

Cross-posted to: Instagram | Amazon | Goodreads | StoryGraph

#booklr#book blog#book blogger#bookish#book review#what happens after midnight#taggartswell#tag swell#lily hopper#kl walther#second chance romance#forced proximity#slow burn#ya romance#ya contemporary#contemporary romance#romance books#romance novels#bibliophile#bookaholic#new adult romance#book lover#book recs#book reader#ya recs

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Essential Tips for Perfecting Your Hardcover Book Printing in Australia

Are you an author, publisher, or aspiring novelist looking to bring your masterpiece to life in the form of a hardcover book? Choosing the right printing service is crucial to ensuring your vision is translated impeccably onto the pages. In Australia, where quality printing services abound, it's essential to know how to navigate the process to achieve the best results. Here are five indispensable tips for perfecting your hardcover book printing in Australia:

Choose a Reputable Printing Service: When it comes to hardcover book printing, quality is paramount. Research and select a printing service in Australia with a proven track record of excellence. Look for companies that specialize in book printing and have experience producing high-quality hardcover books. Reading reviews and viewing samples of their previous work can give you valuable insights into the quality of their printing.

Pay Attention to Paper and Binding Options: The paper and binding choices play a significant role in the overall look and feel of your hardcover book. Work closely with your printing service to select the most suitable paper stock for your content and audience. Consider factors such as paper weight, finish, and durability. Additionally, discuss binding options such as sewn binding or perfect binding to ensure your book's pages are securely held together for years to come.

Optimize Your Design for Print: Designing a hardcover book requires careful consideration of the printing process. Work with a professional designer who understands the intricacies of print design to create a layout that enhances your content and translates seamlessly onto the printed page. Pay attention to factors such as margins, bleed, and color profiles to ensure your design looks stunning in print.

Proofread Diligently: Before sending your book off to print, invest time in thorough proofreading and editing. Even minor errors can detract from the professionalism of your finished product. Consider hiring a professional editor to review your manuscript for grammar, punctuation, and consistency. Additionally, carefully review digital proofs provided by your printing service to catch any layout or formatting issues before printing begins.

Communicate Clearly with Your Printer: Effective communication with your printing service is key to ensuring a smooth printing process. Clearly communicate your expectations, specifications, and deadlines from the outset. Provide all necessary files and assets in the correct format and respond promptly to any queries or requests for feedback from the printer. By maintaining open and transparent communication, you can avoid misunderstandings and ensure that your hardcover book is printed to perfection.

By following these five essential tips, you can navigate the process of hardcover book printing in Australia with confidence and achieve outstanding results. From choosing the right printing service to optimizing your design for print, attention to detail at every stage is essential to creating a stunning finished product that will captivate readers for years to come.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

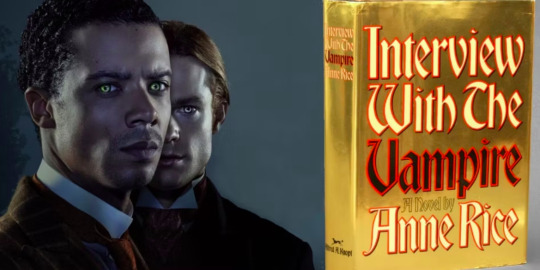

We need to talk about Interview With the Vampire’s biphobia (Part 1: Bi erasure)

Amid rave reviews, praising the new AMC series for “finally letting the vampires be gay”, the conversation about the show’s treatment of bisexuality is silenced. To describe the show’s take on bisexuality in one word, it is complicated. Simultaneously erased, elevated, trodden down, associated with evil, seductiveness, villainy, privilege, freedom, and queerness. Laden with rich meaning, some of the scenes form a master class in cinematic storytelling through bisexuality, while others are the epitome of classic biphobia.

This is going to be a series of articles in which I show how Interview With the Vampire takes the source material’s bisexuality and turns it into ambivalent biphobia, by depicting it as simultaneously oppressive and liberatory. I’ll explore bisexual erasure, the meanings given to bisexuality, and explain how these ultimately reveal bisexuality’s subversive power against dominant social structures.

Let me start with a disclaimer.

Just so we’re clear – this is a great show

Though much complaint is heard from fans of the Anne Rice books for deviating from the original, critics have been praising this show to no end – and justifiably so. The show’s irreverent treatment of the source material is nothing short of a stroke of genius. The showrunners took the original book and ran with it. They spun it into a retelling that is fresh and original, standing on the shoulders of a giant to create something new, while still preserving the core, the heart of the story.

Specifically, the choice of making Louis – originally a slave plantation owner – black, brings a whole new level of meaning, depth, and complexity into the narrative. It exposes the viewers to a culture and experience that the source material could never dream of. It also makes for a brilliant solution to the problem of depicting a white plantation owner as the romanticized protagonist of the story, by literally turning the book’s racism on its head.

Even as its own text, without regard to the source material, this show does its job incredibly well. It’s well narrated, written, and acted. Its beautiful cinematography makes every episode a delight to behold. It is completely legible to people who haven’t read the book, while still adding easter eggs and meta commentary on the original that both enriches and subverts it.

On the whole – I fucking love it.

And therein lies the problem – when something that does so very well on literally every level fails so hard in this.

Bisexuality in the book

[Book spoilers]

Interview With the Vampire is a very bisexual book. Though very little is explicit and on the surface, the subtext is rich with it. From the outset, the interview itself between Louis and Daniel takes place after they cruise each other and then go to Louis’ apartment. Most of the book/the interview itself focuses on his relationship with Lestat, starting with courtship and ending with an embivalent breakup. In addition, Louis tells about his love for a woman named Babette Freniere, which continues even after Lestat turns him into a vampire. When Louis and Lestat turn Claudia, Louis’ feelings towards her aren’t just fatherly, as in the show, but also romantic (yes, Anne Rice has a penchant for p*dophilia). Their relationship is consistently described in terms that blend and obscure the boundary between fatherly and romantic love. At one point in the book, while talking to Louis, Armand calls her “Your lover”, to which Louis replies: “No, my beloved”, emphasizing the complexity and multiplicity of Louis and Claudia’s relationship and feelings for one another. All the while, during this part of the book, Armand also is trying to court Louis (ultimately successfully, once Claudia dies). So, Louis is bisexual.

Moving on, both Interview With the Vampire and the Vampire Chronicles book series in general, make it abundantly clear that Lestat is bisexual. In Interview, he continues to feed on men and women, where bloodsucking is invariab;y described as erotic in Anne Rice’s books – both with the refrain that feeding replaces sex for vampires, and through the erotic language used to describe the act. Lestat is the one to seek out the relationship with Louis and turn him into a vampire. And throughout the Vampire Chronicles, Lestat has relationships, both romantic and erotic, with several women and men.

Daniel is also bisexual. During the Vampire Chronicles, he is shown to have relationships with Armand and Marius, and Anne Rice has spoken multiple times to the fact that all her vampires “transcend gender in their orientation”.

The book is not biphobic in its representation and storytelling. Don’t get me wrong, one can certainly make a case about the fetishization of male bisexuality in the books. It also, of course, links between bisexuality and vampirism, a well rich with meanings that by association imagine bisexuality as innate (the problematic notion that “everyone is bisexual really”), and as predatory and monstrous, dejected and dangerous. The latter meanings, though lovely when reclaimed, carry negative cultural meaning, therefore revealing a negative attitude and fear of bisexuality (=biphobia)*. But because Anne Rice’s vampires are all bisexual, and because they are humanized, romanticized, and eroticized, this doesn’t carry over to a strong negative characterization of bisexual vampire characters.

The show messed this up. And it starts with bisexual erasure.

[* Saying this is not, in fact, biphobic, nor is it a form of respectability politics. It becomes respectability politics when in response, we demand that bisexual characters be made respectable. Pointing out biphobic tropes , in itself, is not biphobic. Honestly this shouldn’t need explaining, but here we are..]

One bi character left standing

Out of three bisexual main characters, only one is left. Where it had the choice of staying true to the bisexual source, the show chooses to erase both Louis and Daniel’s bisexuality – Louis is made gay while Daniel is made straight. First and foremost, this change betrays somewhat of a bifurcated perception of bisexual identity and attraction, i.e. imagining it as “half gay” and “half straight”. One can imagine that the showrunners thought this change made sense as they chose which “half” to go with for each character.

We can only guess what motivated the showrunners to make this change. One option is that they wanted to tick more representation boxes. They knew the series would receive greater acclaim if one of the characters would be “fully gay” rather than just “half”, i.e. bisexual. They may have also felt they were being more faithful to the source material by doing so – as the rave reviews say, letting the story be “actually gay”. Similarly to the above, these two notions also reflect the belief that bisexuality is only “half”, that it is not “fully queer”, or that it’s a “cop out”.

Another reason why leaving Lestat as bisexual while making Louis gay might have made “more sense” to the showrunners is that Lestat is to a large extent the villain while Louis is the victim. The range of meanings associated with bisexuality in culture means people feel more comfortable seeing bi characters in villainous roles, it “makes sense” for people to associate bisexuality with evil. Whereas this has also been the case for representations of gay people in the past, this has overwhelmingly changed over the last 20 years. Though queer coding villains is still a prevalent practice, explicitly gay characters are not so often cast in such a role anymore. But bi characters are.

Yet another possible reason for this is the association between bisexuality and whiteness. After making Louis black, it might have made “less sense” to the showrunners for him to be bisexual, since bisexuality is widely perceived as a white identity (ironically enough, as statistically, bi people are disproportionately people of color). Meanwhile blackness, like gayness, is an oppressed identity that is actually perceived as oppressed. Therefore it makes “more sense” for the black character to bear a gay identity, while the white character is allowed to remain bisexual an imagined marker of “privilege”.

On a more sympathetic note, one can also imagine the showrunners may have wanted to avoid the “everyone is bisexual” trope which is broadly present in the source material. As I noted above, this trope suggests that everyone is actually bisexual. It consigns bisexuality to an eternally latent status, always lurking underneath, but never present in the here and now. Combined with vampirism, it suggests that bisexuality is only possible when one exists outside of society and is able to live a long life. It also imagines bisexuality as supernatural and inhuman.*

[* Again, pointing this out is not biphobic, see above.]

[TW: discussion of p*dophilia]

Another valid reason why the showrunners may have chosen to do this is avoiding the p*dophilic tones in Louis and Claudia’s relationship. Anne Rice was openly supportive of p*dophilia, which is deeply disturbing. In the 1994, there is actually a scene where Kirsten Dunst and Brad Pitt kiss. She was 12 at the time, while he was 29. So I’m genuinely glad and relieved that they decided to leave that part out. However, they absolutely could have done that while letting Louis stay bisexual.

[End of TW]

Whatever the reason, making Lestat the only bisexual character makes him the focal point of bisexuality in the show. He remains to represent it alone, meaning that his depiction, his actions, and his function in the plot make up the whole of the show’s commentary on bisexuality. And the meanings given to his bisexuality in many ways echo the points made above.

In the next part, we’ll delve into the many and complicated meanings that the show attributes to bisexuality through Lestat’s character.

#bisexuality#bi tumblr#bi characters#bisexual characters#interview with the vampire#anne rice#bi media representation

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on the His Dark Materials TV show

Warning Major Spoilers ahead... If you have not yet read the fabulous books or watched the entirety of the story through the long form TV series entitled 'His Dark Materials' or even the film called The Golden Compass, then bare in mind that this discussion might well spoil your enjoyment of Philip Pullman's masterpiece of fiction. I am going to try to take a major dive into the story and offer my critique, which given that I know very little about the critical theory of literature or even how to spell Asriel, might be a bit of a trial!

Still here? OK then, here is my hand, let's take a trip together into the worlds of Dæmons and Dust. From the outset, I cannot promise an impartial review of these works because I absolutely adore them. I may struggle with aspects of them because of the deep emotional scars they touch in my soul, but I continue to love both the books and the person that is Lyra and Pan. I read the books at least once per year and even though I know full well what the Amber Spyglass book is going to do, I always cry at the end because it is so beautifully heart breaking. The books are written for a younger audience than your horrifyingly close to fifty year old reporter and are based upon the work Paradise Lost, by John Milton, which I will admit to you now, I have never read. Maybe that is a task I can try to undertake this year? Hmmm, as if I had not already set myself enough tasks that I am going to struggle to achieve this year!

In 2007, Hollywood released the film, The Golden Compass, the first attempt to bring the story of His Dark Materials to the flickering screen. The first confusion for me was to rename the story from Northern Lights, or His Dark Materials, into The Golden Compass, however there are several reasons for why this was done, some of which include a reference to the original inspiring work of Paradise Lost. However, the film flopped, losing money and support of a wider audience, largely due to the fact that they tried to cram so much into the film from what is a pretty huge book. A young girl called Dakota Blue Richards was cast to play Lyra and she gave us a wonderful, believable representation of Lyra, which is remarkable when one considers what she was given to work with. Sadly this is a comment that can be made for the entire cast of the film to be honest, but the rest of the production was a shocking mess, with often incoherent scenes that rushed past in a blur with little time to digest the events of the book. It was a triumph in that it was even made at all, given the resistance and interference of the studio and even the religious intolerant who claimed the book to be blasphemous (rather proving the point of the book while they did it!). Basically, the cast and crew never had a chance and it was deeply saddening to see the resultant, utterly beautiful looking, film fail. No matter what, I will always be grateful to the crew and cast who tried so hard to make what was probably an impossible dream come true. What good can be taken from the films though is the wonderful portrayal of Mrs Coulter by Nicole Kidman (a person who has in the past had dealings with horrendous theocratic organisations. However, that is a story best left to others to tell.) and Lord Asriel as played by the future Bond, Daniel Craig. Both of them gave wonderful performances and gave Dakota Blue Richards the perfect parents to play Lyra against.

These books are huge and deeply immersive which is one of the problems facing those trying to turn them into other forms of entertainment. I have listened to the Radio play that aired on the BBC a few years ago and enjoyed it to some degree, but again it was limited by the time it had to tell the story. If you are clever with the internet and don't mind listening to a play, this can still be found on line, albeit with some slightly naughty Detective skills. If you want a hint... Try looking for the Internet Archive. Who knows what you will find?

In 2017, the first of The Book of Dust was released by Pullman. Like many of you, I always find that the end of the Amber Spyglass leaves a hurt feeling of grief in the chest when the last page in turned. Yes, some short stories have been released by Pullman, in particular Lyra's Oxford does go into some small detail of her life post His Dark Materials, but this new trilogy promised further adventures for our beloved Lyra. What we got however was thus far something of a mixed bag, with La Belle Sauvage being more of a prequel that fills out the story of Lyra's birth with details of the great flood and goes on to explains how a young Malcolm Polstead and, his often enemy, Alice come to care for the infant Lyra. Along the way they encounter agents working against the Magisterium (the theocratic rulers of Lyra's world), faeries and other complicated beings all of whom have an interest in young Lyra. It was an adventurous enough read, but it did not really fulfil that desire to discover more about Lyra and her adventures after her return to Oxford.

Two years later in 2019 (just before the world went tits up with covid!), Pullman released the second in the Book of Dust trilogy, The Secret Commonwealth. It was from the outset, a deeply disturbing book and anyone hoping to find a happy and peaceful Lyra and Pan, were instead given a broken and severely depressed Lyra, who continually argues with Pan, right up until in a silent mood, he leaves her. As I was reading this, I had not long finished a course of therapy that had helped me come to terms with my own past and mental health, so seeing Lyra and Pan as wounded as they were carried a lot of extra grief that I could understand. I knew what it felt like to be at war with oneself and I could feel both of their pain in the difficult story. This was a more mature story than Northern Lights or even The Amber Spyglass, as such the themes were more mature and darker. It is a sad fact that young people suffer, often undiagnosed, with mental health problems and this book does not shy away from this fact, no matter how painful it can be. Desperate to see Lyra and Pan come back together as a whole person once again, I sped through the book, missing the finer detail and at the end was left heart broken and hanging onto a cliff with less hope than my favourite cartoon Coyote!

With my second reading of the book, I went more slowly and absorbed the prose and its meaning. I followed Lyra as she travelled, following her heart trying to locate Pan and meeting people along the way who had also lost or even due to horendous poverty, sold their Dæmons. The lore of the Dæmon has changed with this book. The bond can be broken, when not fully severed and a replacement can be found. If there is a sadder parable of our money obsessed society, then I am yet to read it. Hidden deep within the despair of Lyra and Pan, there is a beauty in the world and towards the end, we see Pan helping a child who has suffered a terrible loss. The child in the book is named after one of the victims of the Grenfell fire in London and in many ways, this is a beautiful eulogy to her.

As heart breaking as the book is, it continues to bring a taste of blood to the mouth as Lyra goes from place to place searching for Pan. The worst part of this journey is no doubt when Lyra is sexually assaulted on a train, by soldiers who have no respect for a woman, let alone a woman without a Dæmon. If you did not cry reading this book, then you are a stronger reader than I because I cried several times during both my first and second reads of this book. You may ask why, but the reason is simple, Lyra is our beloved heroine. She may have started out as a deceitful, unwashed brat, but she ended the story with a broken heart, but somehow still full of love and wisdom. In some regards, it is hard to correlate the exhausted, heart worn but hopeful Lyra of the Amber Spyglass with that of the closed off, angry Lyra of the Secret Commonwealth. Yet given the political nature of these books, I am sure that even the most disinterested of readers can feel the depth of despair for our modern times ringing like a funeral bell through out the prose. It has been nearly four years since we were left wondering if Lyra and Pan would reconcile and every day when I look up at my copies of these books, I feel a little pain in my heart.

So it was that in 2019, the BBC and HBO released their attempt to put His Dark Materials onto the big screen, well the big TV screen in my home anyway, with eight weekly episodes of the first book, cleverly combined with aspects of the second so that the meeting of Lyra and Will happened sooner than we would otherwise have got. Now it is cards on the table time and I have to be honest here. I did not go willingly into the show. I had a sore heart from the film and I desperately did not want to witness another botched attempt or see another young Lyra broken by process of telling her story. This time Lyra was portrayed by a young Dafne Keen, whose father portrayed the undeniably vile, Father MacPhail. I did not want to get my hopes up and was promptly treated to some things that as a dedicated reader of the books, I found strange or in some cases not fully truthful to the letter of the book. However I persevered and struggled through some aspects of the series such as the Gyptian culture which was explored far more visibly and audiably than I was expecting and come the end, I was left with mixed feelings. Dafne Keen is undoubtedly a very good Lyra, within what her script gives her. Amir Willson makes an interesting Will and seeing him as mixed race makes him a far more interesting person and does give an extra depth to some of his Mother's suffering. But it did not have the Lyra and Will I wanted. There was also the concerns over how they were going to film some of the later scenes, because as actors, both of them were still children when filming the series.

Series two came upon us quickly enough and was one episode short of the first series (or season for those of an American culture), but given the source material, some of which had already been covered in series one, this was not a surprise and it gave us again a few changes and differences. As with series one it was hard to fault the choices, given how hard it must be to make a show about something as expansive as war with God across the multiverse! I purchased the two seasons on DVD as soon as they became available (something that DisneyPlus really needs to think about for those of us with incomplete Clone Wars DVD sets!) and binge watched them through, enjoying them more and more with each viewing. I understood the changes and why they had been made, the show was utterly beautiful and the sets used were fantastic. The Dæmons were beautifully animated, with puppets used on set to make the interactions with their people more believable. Pan was wonderful, the Golden Monkey terrifying and Stelmaria was beautiful. I was at peace with the series and I was looking forwards to the third and final season.

The third season seemed to hit the airwaves almost unannounced. It almost felt as if the BBC were somehow ashamed of their beautiful series. I have been following Pullman for some time on Farcebook and the only update I saw from him was an advert for a re-release of the original trilogy and then an actual paper version of 'The Collectors', a short story about a very curious pair of artefacts from Lyra's world. I caught episode one and instantly felt the bad taste in my mouth of wrongness. Changes yet again, Mrs Coultier was hiding in a cottage on the coast and not a cave in the Himalayas. The young child who helps her was deaf and not Asian. Will did not meet the scary paedophile priest... Actually, that was probably a good thing! Asriel was jetting about gathering troops, rather than them answering his call to arms. All of these changes probably made the show easier to follow if you have not read the books, but as a close to obsessive reader of the books, some of the changes felt wrong.

However the BBC in their wisdom put the entire series on their i-Player service and I was able to sit through a couple of episodes, rather than wait weeks at a time to get where I wanted to be. (Again, Disney, I know why you do it, but one episode a week... Really?) The misery of Solstice, Christmas, Yule or whatever we choose to call this time of year, got in the way and despite having the joy of my friends around me, His Dark Materials got put to one side until I had a quiet day to go through it. That was when I caught the flu and lost my voice. Even as I type this, I am still not able to talk above a whisper and trying to do so, seems to make things worse. Getting old sucks.

So sat in bed, unable to speak, sick with a winter cold, I started to watch episodes three to eight and it was traumatic. There was a lot of changes and again I understand why some of them were done, because not every viewer will have torn the books apart the way I have over the years. However, enough remained the same that I could still follow the story and I did wonder at some of the changes made, until you think about how much visual effects cost and what the budget would have been for this whole show.

The actor Simone Kirby, portraying Mary Malone, was perfect and she has been since she first appeared in the series, so much so that I completely believed that she was Mary. Yet when it came to her major discoveries about Dust and the importance of the Mulefa and their world, so much was cut away, it was almost like a crude orchidectomy done with rusty scissors! Mary meets and then spends time with Atal, her friend among the Mulefa. They share time together, chat about the nature of life, the universe and everything... Sorry, wrong book. But Mary and Atal are important, it is together that the pair of them help Mary find the answer to Sraf, first in seeing Sraf and then in discovering why the trees are dying because of a lack of Sraf. Mary as the serpent must have knowledge to share with Eve, yet the time allotted to her on screen meant that a great deal of her story was trimmed away or flashed over in seconds and we never got to know Atal, one of the truly beautiful souls of the story.

The end of the second series left us with Mrs Coulter taking Lyra away in a trunk on a ship. Will had found and then lost his father while Lee Scorsby had died defending the very same man. We find Mrs Coulter hiding in her little house, Will arrives, they talk. He rescues Lyra during a raid by the Magisterium and while cutting an exit, the subtle knife breaks as Lyra's Mother pushes him to think of his own lost parent back in the human world. It is different enough to grind my gears, but close enough to keep me watching. The calls of Roger are hinted at, but never really clear and it is with some surprise that Lyra announces her quest to enter the world of the dead to find Roger to apologise for his death. Again we have the strange arguments between Lyra and Will, a conflict that never happened in the books. They believe in each other and as they journey, they are falling in love, not overcoming each other. These slightly argumentative scenes felt like sand in a gear box, things work, but you know damage is being done. Iorek agrees to mend the subtle knife, but the discussion between him and Will is almost nonexistant. The warning about the nature of the knife had none of the brevity that it has in the book, but the reforging of the blade was at least a pretty moment. The biggest problem though was that it was horribly rushed and yet they filled in the episodes with stuff that we did not need to see. Why did we need to see Asriel gathering an army... of mainly one man who he took an eternity to persuade, when in the book he raises his call to arms and they simply come. At the cost of important detail, they gave us chaff.

The land of the dead was bleak, sad and grim. Again there were differences, but until the boatman, nothing of consequence. Lyra meets her death, Pan is scared and Will remains stoic. That moment on the boat though, the first heart break between Pan and Lyra when she is told that Pan cannot enter the land of the dead. That was there, but the boatman was more human, which in some ways gave it a softer edge. Making the boatman a well dressed man in his early sixties took away the fear of the cloaked Charon, the creature that may have been a man, but could have been something far more aged and far, far worse. The betrayal of self as Pan is ripped from her soul and Will loses the Dæmon he never knew he had, is still heart breaking, but where in the book time is given to Pan attempting to keep Lyra with him, making her sacrifice all the more important, the show quickly edits past it. Again, time, technical effects and expense cannot compete with the imagery of a few words in a book. To even come close to the scope and the detail of the book, the show needed at least ten hour long episodes per book and a budget of billions. Such things were never going to be possible, so instead we can only be grateful for what we got and the river crossing was still heart breaking as Will and Lyra clung together in agony.

The land of the dead was truly haunting, the sad broken spirits of those trapped there, taunted and berated for every terrible thing they had done, by the impossibly ancient Harpies. The term Harpy comes from ancient Greek and Roman myths, being a form that is half woman and half bird. Basically a bird with the torso and face of a woman. What was presented here was so much more creepy, a scaly filthy tortoise like winged creature filled with hatred and bile. The scene of Lyra telling tall tales was cut for time, but we can assume that she had by this time learned that lying was bad for them. We did have some moments of true horror as she is forced to confront her loss of Pan and the awful fact that there is truly no way out of the land of the dead. The book makes a deliberate choice to have the spirits unable to touch, embrace or hug. Yet again, the horror of finance raised its head and we see actors with grey scale make up and lots of red eye shadow hugging Lyra. As lovely as it was to see Lyra reunited with Roger, the subtle difference gave this a more bleak, angry feel than the loss and love of the book. The difficulty for the production team was also the casting of children for the roles of er... children. Roger has clearly grown up and his buck toothed smile of a ten year old boy has been replaced by the teenage cool of a lad who is nearly a full grown man. They did as well as they could within the budget and Roger was there. Death has clearly broken his voice and made him a foot taller though!

The weaponisation of Mrs Coulter against Lyra, using the tuft of hair she took from Lyra's head was terrifying. Having written out some of the more helpful moments of the book, such as the Galivespians, the energy bomb was never not going to explode. Within the constraints of the TV show, they did it very well and the chasm that opens is destructive in ways that I never connected in the book. The Dæmon that flies above the opening and is sucked down, causing the death of Queen Ruta Skadi was tragic. She did not so much die as simply fall into nothingness and cease to exist. It was utterly brutal. The spectres raided the camp of Asriel and the defence against them was to have Mrs Coulter who had escaped once again from the Magisterium, having come and gone like a welcome guest between camps. In a moment of pure film magic, Ruth Wilson raised her hands and gave the spectres a force shove that Clone Wars ere Obi-Wan would have been proud of. The result was that the entire army of spectres evaporated, never to be seen again. Once again this must come down to cost. The spectres were beautiful in their oil like liquidity. Animating an army of them, fighting see through ghosts who have no Dæmon would have run into the millions of Dollars. So I forgive them for their use of the force, even if for a brief moment, Mrs Coulter became a Jedi!

The fight with Metatron, AKA the Regent of the Clouded Mountain, ruling in the name of the Authority was fabulous. The deception by Mrs Coulter was a dark moment in the book, but she carries it well, hiding what little goodness she has left to fool not a God, but a man who lusts after her. The fight in the show was almost as brutal, Asriel is not as broken as he should be, but with the love of his life, Mrs Coulter, they both drag the Regent into the abyss. As with Ruta Skadi, this is not death but something far, far worse. This of course leads to Lyra and Will finding the casket that contains the withered remains of the authority. In the book it is stated that cutting him free of his prison is an act of kindness for a being so ruined by age as to be insensible. With his atoms reaching the gentle air currents, the Authority is gone forever, along with his regent.

At this moment in the book, the two children find their lost Dæmons and Will cuts through into the world of the Mulefa, grabbing a Dæmon each, they jump through. It is at this moment that they realise that Will has grabbed Pan and Lyra has taken Will's unnamed Dæmon. The thrill of excitement, of something beautiful between them hits them both hard as Will seals the window after himself.

In the series, things are done differently and Will tells the Dæmons to jump through and they will follow on later. Sure enough a short while later they do jump through, but only after Lyra witnesses the death of the Mother, as the Golden Monkey turns to particles. I do not know why they felt that Lyra needed that moment of finality, because in some regards it felt cruel. Once in the world of the Mulefa, there is still a mild hostility between Lyra and Will. They have been through so much together, but do not have that trust of each other yet, which seems strange and almost heretical compared to the book. Their love does grow, but only after a few misjudged moments between them. The book explains that from the moment Mary finds them, she can see the love, the powerful bond between them. She knows that they must heal and save the worlds so does her job, she plays the serpent teaching them about growing up, finding a meaning in life and love. Again there was a slight change in the series from the book, but for me this one worked far better. Mary recalls how she knew that she could not be a Nun any more and it was when a woman showed her an act of love by passing her a simple sweet. This was a moment that awoke something in Mary and it is implied that Mary investigated this attraction. In the book, the tempter was a man and to be honest as a rainbow person, who knows how the Church at large feels about people like me, making Mary a lesbian or at least not fully heterosexual was the right move.

With rather a lot of narrative exposition, Lyra and Will learn that they must not only return to their own worlds, they cannot create new windows and all of the old ones must be sealed to prevent the loss of Dust into the endless void. In the book, Pan lets out a howl of pain that frightens small animals in their holes for ever. Defeated at last, Lyra cries, comforted only by the one soul who can do so, but who she must lose forever. The TV show does allow this to play out and it is painful to watch. The acting of Dafne Keen and Amir Wilson was superb and I genuinely believed their tears as my heart was broken.

The insight of Pullman when he wrote this scene is not to be underestimated. Lyra and Will are forced apart, their sacrifice is explicit. They could stay in the world of each other, but to do so is to lose health and to die, leaving one with the unbearable horror of watching their love die. Leaving the window open will bring an end to Dust and everyone dies. They sacrifice their love for each other to save those who inhabit every realm, including the world of the dead, for every soul that has ever existed can be free from the horror of purgatory and they do so, while their own hearts are torn apart.

Whenever I read the Amber Spyglass, I need a moment of silence when the last page is turned. It feels somehow reverential, as if I too have lost a part of my heart and the grief I feel is very real. It stirs in me every loss I have felt throughout my life, whether that be of parents, lovers, mentors or friends. Every fibre of pain is stirred, every wound cleaned out and shown love. There is however one loss that I dread with all of my being, a loss so great that every person in love fears it. Yet as Maarva Carassi Andor states so bravely to her Son (in the fantastic Disney Plus Series Andor), “that's just love.”

The themes of the book are truly epic, especially for a book aimed at youthful readers. The contemporaries of the time were the likes of Harry Potter, which I am sure touched some people's hearts. Like His Dark Materials, Potter was accused of turning children away from faith, but if it ever did, it was not through clever writing. With His Dark Materials, Pullman asks the young readers to question why they must bow down to theocracy. He tells them to give thought to dogmatic faith and he gives them a parable with which they can understand how religion can destroy love and hope and understanding. The big theme of the Magisterium is how they want to stifle conscious thought. When it takes the Vatican four hundred years to apologise for the destruction of a man who put forward the idea that the Earth is not the centre of the solar system, we can see where the ideas of a toxic theocratic system comes from. With every Holy War, with every hypocritical theologian and with every repressed adherent to religious law, we can see Pullman's point. His Dark Materials is a story of young people on an adventure, but it is also a story about the importance of innocence not corrupted by dogma, just as it is a story about fighting for the liberty to think for oneself. It is my firm belief that Pullman's work is an important piece of youth literature, it is also more than that and is worthy of the awards it has won. The TV show may not have stuck rigidly to the book, but the message remains the same and that is the important part. So I applaud the series, I think that it achieved great things and it did this despite the corruption that killed its big screen predecessor.