#Nineteenth century Indian model

Text

Why women presented as men, in their own words

Most of these working-class women appear to have begun their "masculine" careers not because they had an overwhelming passion for another woman and wanted to be a man to her, but rather because of economic necessity or a desire for adventure beyond the narrow limits that they could enjoy as women. But once the sexologists became aware of them, they often took such women or those who showed any discontent whatsoever with their sex roles for their newly conceptualized model of the invert, since they had little difficulty believing in the sexuality of women of that class, and they assumed that a masculine-looking creature must also have a masculine sex instinct.

Autobiographical accounts of transvestite women or those who assumed a masculine demeanor suggest, if they can be believed at all, that the women's primary motives were seldom sexual. Many of them were simply dramatizing vividly the frustrations that so many more women of their class felt. They sought private solutions to those frustrations, since there was no social movement of equality for them such as had emerged for middle-class women. Lucy Ann Lobdell, for example, who passed as a man for more than ten years in the mid-nineteenth century, declared in her autobiography: "I feel that I cannot submit to all the bondage with which woman is oppressed," and explained that she made up her mind to leave her home and dress as a man to seek labor because she would "work harder at housework, and only get a dollar per week, and I was capable of doing men's work and getting men's wages." "Charles Warner," an upstate New York woman who passed as a man for most of her life, explained that in the 1860s:

“When I was about twenty I decided that I was almost at the end of my rope. I had no money and a woman's wages were not enough to keep me alive. I looked around and saw men getting more money and more work, and more money for the same kind of work. I decided to become a man. It was simple. I just put on men's clothing and applied for a man's job. I got it and got good money for those times, so I stuck to it”

A transvestite woman who could actually pass as a man had male privileges and could do all manner of things other women could not: open a bank account, write checks, own property, go anywhere[…]

Ralph Kerwinieo (nee Cora Anderson), an American Indian woman who found employment for years as a man and claimed that she "legally" married another woman in order to "protect" her from the sexist world, also expressed feminist awareness for her decision to pass as a man:

“This world is made by man—for man alone.... In the future centuries it is probable that woman will be the owner of her own body and the custodian of her own soul. But until that time you can expect that the statutes [concerning] women will be all wrong. The well-cared for woman is a parasite, and the woman who must work is a slave.... Do you blame me for wanting to be a man-free to live as a man in a man-made world? Do you blame me for hating to again resume a woman's clothes?”

There must have been many women, with or without a sexual interest in other women, who would have answered her two questions with a resounding "no!"

From “Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers.” The economic reason for women to pass as men is almost never mentioned, funny that!

#mypost#radical feminism#lesbian women#bookcitation#the more things seem to change#gnc women#100 notes tag

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

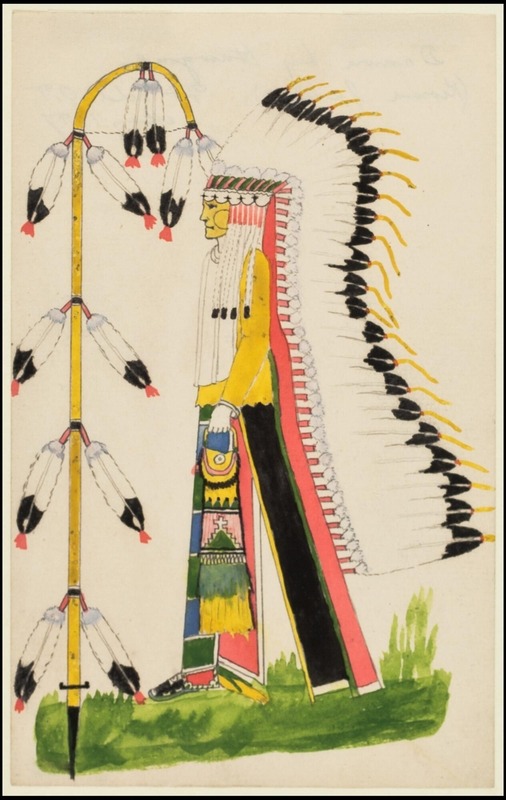

Silver Horn drawings, 1897-1921

Silver Horn drawings, 1897-1921

“Silver Horn (1860-1940), a Kiowa artist from the early reservation period, may well have been the most prolific Plains Indian artist of all time. Known also as Haungooah, his Kiowa name, Silver Horn was a man of remarkable skill and talent. Working in graphite, colored pencil, crayon, pen and ink, and watercolor on hide, muslin, and paper, he produced more than one thousand illustrations between 1870 and 1920. Silver Horn created an unparalleled visual record of Kiowa culture, from traditional images of warfare and coup counting to sensitive depictions of the sun dance, early Peyote religion, and domestic daily life. At the turn of the century, he helped translate nearly the entire corpus of Kiowa shield designs into miniaturized forms on buckskin models for Smithsonian ethnologist James Mooney.”

-- Silver Horn: Master Illustrator of the Kiowas by Candace S. Greene

The artist Elbridge Ayer Burbank traveled to Indian reservations in the late nineteenth century to paint the portraits of Indigenous peoples. Burbank traveled to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, on three occasions; it was there that the Kiowa artist Silver Horn sat for him for at least two portraits.

Silver Horn had been an established artist among the Kiowa since the 1880s. In 1899, he became interested in Burbank’s “naturalist” technique, and he observed the American artist as he painted other subjects. With Burbank, Silver Horn studied the art of modeling faces and individual portraiture. He experimented with this style in a series of individual portraits of people and animals, most of which he sold to Edward E. Ayer, before abandoning the style in favor of work that was more stylistically Kiowa.

Silver Horn drawings, 1897-1921

The 123 pieces by Silver Horn in the Newberry’s Ayer Collection demonstrate that his experimentation took him away from narratives about community to work that featured individuals. This makes the body of work held in the collection stylistically distinct from both the earlier and later periods of Silver Horn's work.

–former Ayer Reference Librarian Seonaid Valiant (abridged from original post)

View Silver Horn's drawings or all of the Edward E. Ayer Collection at Newberry Digital Collections

#newberry library#libraries#special collections#archives#native american history#native american art#silver horn#kiowa#collection stories

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coral today is an icon of environmental crisis, its disappearance from the world’s oceans an emblem for the richness of forms and habitats either lost to us or at risk. Yet, as Michelle Currie Navakas shows in her eloquent book, Coral Lives: Literature, Labor, and the Making of America, our accounts today of coral as beauty, loss, and precarious future depend on an inherited language from the nineteenth century. [...] Navakas traces how coral became the material with which writers, poets, and artists debated community, labor, and polity in the United States.

The coral reef produced a compelling teleological vision of the nation: just as the minute coral “insect,” working invisibly under the waves, built immense structures that accumulated through efforts of countless others, living and dead, so the nation’s developing form depended on the countless workers whose individuality was almost impossible to detect. This identification of coral with human communities, Navakas shows, was not only revisited but also revised and challenged throughout the century. Coral had a global biography, a history as currency and ornament that linked it to the violence of slavery. It was also already a talisman - readymade for a modern symbol [...]. Not least, for nineteenth-century readers in the United States, it was also an artifact of knowledge and discovery, with coral fans and branches brought back from the Pacific and Indian Oceans to sit in American parlors and museums. [...]

---

[W]ith material culture analysis, [...] [there are] three common early American coral artifacts, familiar objects that made coral as a substance much more familiar to the nineteenth century than today: red coral beads for jewelry, the coral teething toy, and the natural history specimen. This chapter is a visual tour de force, bringing together a fascinating range of representations of coral in nineteenth-century painting and sculptures.

With the material presence of coral firmly in place, Navakas returns us to its place in texts as metaphor for labor, with close readings of poetry and ephemeral literature up to the Civil War era. [...] [Navakas] includes an intriguing examination of the posthumous reputation of the eighteenth-century French naturalist Jean-André Peyssonnel who first claimed that coral should be classed as an animal (or “insect”), not plant. Navakas then [...] considers white reformers, both male and female, and Black authors and activists, including James McCune Smith and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and a singular Black charitable association in Cleveland, Ohio, at the end of the century, called the Coral Builders’ Society. [...]

---

Most strikingly, her attention to layered knowledge allows her to examine the subversions of coral imagery that arose [...]. Obviously, the mid-nineteenth-century poems that lauded coral as a metaphor for laboring men who raised solid structures for a collective future also sought to naturalize a system that kept some kinds of labor and some kinds of people firmly pressed beneath the surface. Coral’s biography, she notes, was “inseparable from colonial violence at almost every turn” (p. 7). Yet coral was also part of the material history of the Black Atlantic: red coral beads were currency [...].

Thus, a children’s Christmas story, “The Story of a Coral Bracelet” (1861), written by a West Indian writer, Sophy Moody, described the coral trade in the structure of a slave narrative. [...] In addition, coral’s protean shapes and ambiguity - rock, plant, or animal? - gave Americans a model for the difficulty of defining essential qualities from surface appearance, a message that troubled biological essentialists but attracted abolitionists. Navakas thus repeatedly brings into view the racialized and gendered meanings of coral [...].

---

Some readers from the blue humanities will want more attention, for example, to [...] different oceans [...]: Navakas’s gaze is clearly eastward to the Atlantic and Mediterranean and (to a degree) to the Caribbean. Many of her sources keep her to the northern and southeastern United States and its vision of America, even though much of the natural historical explorations, not to mention the missionary interest in coral islands, turns decidedly to the Pacific. [...] First, under my hat as a historian of science, I note [...] [that] [q]uestions about the structure of coral islands among naturalists for the rest of the century pitted supporters of Darwinian evolutionary theory against his opponents [...]. These disputes surely sustained the liveliness of coral - its teleology and its ambiguities - in popular American literature. [...]

My second desire, from the standpoint of Victorian studies, is for a more specific account of religious traditions and coral. While Navakas identifies many writers of coral poetry and fables, both British and American, as “evangelical,” she avoids detailed analysis of the theological context that would be relevant, such as the millennial fascination with chaos and reconstruction and the intense Anglo-American missionary interest in the Pacific. [...] [However] reasons for this move are quickly apparent. First, her focus on coral as an icon that enabled explicit discussion of labor and community means that she takes the more familiar arguments connecting natural history and Christianity in this period as a given. [...] Coral, she argues, is most significant as an object of/in translation, mediating across the Black Atlantic and between many particular cultures. These critical strategies are easy to understand and accept, and yet the word - the script, in her terms - that I kept waiting for her to take up was “monuments”: a favorite nineteenth-century description of coral.

Navakas does often refer to the awareness of coral “temporalities” - how coral served as metaphor for the bridges between past, present, and future. Yet the way that a coral reef was understood as a literal graveyard, in an age that made death practices and new forms of cemeteries so vital a part of social and civic bonds, seems to deserve a place in this study. These are a greedy reader’s questions, wanting more. As Navakas notes in a thoughtful coda, the method of the environmental humanities is to understand our present circumstances as framed by legacies from the past, legacies that are never smooth but point us to friction and complexity.

---

All text above by: Katharine Anderson. "Review of Navakas, Michele Currie, Coral Lives: Literature, Labor, and the Making of America." H-Environment, H-Net Reviews. December 2023. Published at: [networks.h-net.org/group/reviews/20017692/anderson-navakas-coral-lives-literature-labor-and-making-america] [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

DAY 5525

Jalsa, Mumbai Apr 2, 2023 Sun 11:49 PM

Birthday Ef

🪔 .. April 03 .. birthday wishes to Ef Haarsha Balraj from South Africa .. Ef Krishna urf Kris Dwivedi from Bilaspur CG .. and Ef Divyansh Rawat from Lucknow .. love and happiness .. ❤️❤️❤️🌿 and all the good wishes from the family Ef

..

and the Sunday meetings at the Gate be in preference of course .. hence here

And the very revealing aspect for the coming day be that on April 3, for the first time an adventure took place .. the first plane to fly over the Everest .. in the year 1934 , apparently ..

Justification :

📌 .. and on this day .. April 3, 1933 .. conquering the impossible .. happened the first fly ever over Everest 🏔️ .. by two British aircraft of type Westland Wallace bi-planes .. crewed by Squadron Leader Douglas-Hamilton and Colonel LVS Blacker in one and Flight Lieutenant MacIntyre and Mr SR Bonnet in the other .. they took off from Lalbalu aerodrome, near Purnea, India .. the flight lasted for around three hours, covered a return distance of 320 miles reaching nearly 30,000 feet clearing the mountain by a reported 100 feet .. close range photographs of Mt Everest proved the achievement which previously was not possible to any airplane ..

further justification -

the peak , the highest point on Earth .. the mountain , the Himalayas and the feat that seems to this generation to be no big deal, because they are unaware of the conditions and circumstances that prevailed then ..

Everest .. named by the British when they ruled over India ..

In the nineteenth century, the mountain was named after George Everest, a former Surveyor General of India. The Tibetan name is Chomolungma, which means “Mother Goddess of the World.” The Nepali name is Sagarmatha, which has various meanings.

Sagarmatha .. ‘sagar’ , the Ocean .. ‘matha’ churning .. and the Indian mythology that the Oceans were churned by the mountain to produce the ‘amrit’ ..

my interpretation .. though the knowledge from the records says this :

Sagarmatha is a Sanskrit word, from sagar = "sky" (not to be confused with "sea/ocean") and matha = "forehead" or "head", and is the modern Nepali name for Mount Everest.

the Goddess of the Sky .. in Tibet it is addressed as

Therefore, the historic, local Tibetan name for Mount Everest is Chomolungma, also spelled Qomolangma, meaning "Goddess Mother of the World." Chomolungma is pronounced "CHOH-moh-LUHNG-m?." The Nepali name for Mount Everest is Sagarmatha, meaning "Godess of the Sky." Some refer to the entire massif of peaks as ...

and the many adventure stories on the Sagarmatha prevail ..

And the great thrill at the time of a shooting in Nepal, when I went on a plane that flew us right next to the Everest and the experience almost unreal ..

Such be the moments of remembrance ..

It was a touristy matter and many such flights I do believe operate from Kathmandu, Nepal for the pleasure of tourists .. even now ..

Its majesty has never reduced despite the conquering of it by several now .. and the very sight of which evokes so much wonder .. the wonder of the Gods .. the makers that introduced us to us all .. and the reason of its formation .. that the entire subcontinent now known as India was a part of the continent of Africa, at Egypt .. and many millions of years ago the entire subcontinent broke away from the mother board and shifted travelled over the Indian Ocean, to the Eastern sub continent and attached itself there .. the impact of the joining of the land mass being so great , it formed the realm, now known as the Himalayas !!

I do not have authenticity on this , but it does seem to be believed , historically and geographically .

and the day in recuperation and the meeting at the Gate , of the ever present well wisher ..

Amitabh Bachchan

and the signature above out of place , because the icon that opens the Desktop to search the sign is JUST not appearing ..

and this has been on several times before too ..

this model of the updated Mac, the Ventura is absurd and has created many problems ..

deliberately done to attract more when the changed model is brought out ?? marketing and manufacturing often does that .. the deliberation to access the mode of investing in the latest and doing away with the present ..

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

A review of “Persophilia’ of Hamid Dabashi

“Shaj Mathew reviews Persophilia

Hamid Dabashi. Persophilia: Persian Culture on the Global Scene. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015. 296 pp.

Review by Shaj Mathew

28 November 2018

In Persophilia, Hamid Dabashi explores the consequences of the European fascination with all things Persian, examining texts by Montesquieu, Voltaire, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich Nietzsche; artwork by Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse; the scholarship of E. G. Browne and Annemarie Schimmel; and even the films of Abbas Kiarostami. Dabashi narrates a dynamic process whereby Persian culture travels outside of its imperial courts, becomes the idée fixe of European artists and intellectuals, and returns from Europe utterly transformed by its cross-cultural and colonial encounters. In recovering this lively but largely unacknowledged artistic and critical circuit of exchange—which begins in seventeenth-century Europe, becomes prominent in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, and continues into the present—Dabashi models a vein of cross-cultural comparison that scholars of all disciplines should heed.

Dabashi investigates the effects of European (and later American) persophilia through an engagement with Edward W. Said, Raymond Schwab, and Jürgen Habermas. Said and Schwab offer causal explanations for Europe’s interest in the so-called Orient. For Said, Europe created knowledge about the “Orient” in order to dominate and colonize it; for Schwab, European artists viewed the “Orient” as an imaginative or artistic substrate. But for Dabashi, “abandoned in both their projects is the fate of the Orientalized societies themselves—or what happens to Persian, Indian, Arabic, or Chinese literary and artistic traditions (and the emerging public spaces that are hosting them) once they have been translated into a European context” (p. 9). To correct this lack, Dabashi turns to Habermas, whose concept of the public sphere allows Dabashi to provide an account of the effects of persophilia that is neither cultural (Schwab) nor political (Said) but social.

This social or societal account of persophilia obviates two biases that tend to dominate critical thought about the postcolonial state: the critique of European Orientalism (which, for Dabashi, “paradoxically assigns universal agency to a Eurocentric conception of the world”) and a radical anti-Western nationalism (p. 206). Although “both sides of this binary—the critique of Orientalism and the appeal of nativism—are both necessary and even logical for the historical circumstances in which they were launched,” Dabashi writes, “at the same time they have both come together paradoxically to rob the postcolonial person of historical agency and moral and authorial imagination” (p. 206). Dabashi’s attempt at restoring agency and imagination to the “postcolonial person” rests on the following claims about the cycle of European persophilia: Persian culture exited its royal courts and entered the emerging European bourgeois public sphere through art, literature, and philology, largely in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; this European bourgeois public sphere became transnational in light of this encounter with Persia (and other cultures); this newly transnational public sphere periodically reentered Persia through the circulation of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century texts and through the twentieth-century colonial encounter; and finally, the appropriation of the transnational public sphere by twentieth-century Persians provided them with the tools to resist European imperialism. With each stage of persophilia—from Persia, to Europe, and back—Dabashi underscores the fact that the ideas and texts being exchanged underwent mutations.

Dabashi’s argument unfolds over twelve brief chapters, each of which describes a cycle of persophilia organized around one or two literary or scholarly figures. In chapter two, for example, he describes the windy path of Montesquieu’s Persian Letters (1721), which was inspired by the travels of two Frenchmen to Isfahan in the seventeenth century. Persian Letters of course reverses that voyage, and describes, in epistolary fashion, the satirical observations of two Persians in France; Dabashi’s gloss of Persian Letters allows him to claim that European persophilia was at the heart of the European Enlightenment. In support of Persophilia’s overall argument about cultural flows, Dabashi then demonstrates how Montesquieu’s persophilia came to influence Persian writers themselves. Accordingly, Dabashi zooms in on one Persian intellectual, Mirza Fath Ali Akhondzadeh (1812–1878), who wrote his own epistolary work, the Correspondences of Kamal al-Dowleh (Maktubat-e Kamal al-Dowleh; 1863), after being exposed to the ideas of Montesquieu as well as those of Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Akhondzadeh was a prolific dramatist and essayist whose writings often transliterated words such as “civilization” and “despotism” directly into Persian—“a clear indication,” for Dabashi, that these concepts “entered Persian prose directly under the influence of Montesquieu and other French Enlightenment thinkers” (p. 56). Throughout his wide-ranging career, Akhondzadeh also launched a campaign to latinize the Persian alphabet and debated the merits of liberal democracy. In short, his intellectual production, originally inspired by persophilic European thinkers such as Montesquieu, helped open a public sphere in Persia—a prime example of how Persian culture drifted into Europe and returned to Persia to catalytic effect.

Chapter four, entitled “Goethe, Hegel, Hafez, and Company,” is similarly exemplary of Dabashi’s argument. Here he describes how Goethe’s fascination with Hafez and Saadi Shirazi, newly translated into German during his lifetime, led to the publication of the West-östlicher Divan in 1819. Likewise, for G. W. F. Hegel, these translations created an image of Persia against which he could define European thought in his philosophy of world history. For many German romantic thinkers of the early nineteenth century, classical Persian poetry—with its strains of self-annihilation and rebirth—fed into a form of nationalist mysticism that would ultimately provide cover for the political repression of liberal thought. Romantic beliefs proliferating in nineteenth-century Germany, influenced by their appropriation of Persian and “Sufi” poetic mysticism, had “a joint proclivity toward political absolutism” that reentered Persia in the twentieth century through the thought of Seyyed Hossein Nasr (p. 100). Under the sway of the Swiss-German mystic Frithjof Schuon, Nasr would launch a critique of modernity that “had a direct root in these German sources of romanticism, mysticism, and fascism” (p. 101). Nasr’s antimodern ideology would provide cover for both the Pahlavi dynasty and its destroyer, Ayatollah Khomeini.

The chapters I have sketched above are emblematic of Dabashi’s method in this book, which regularly marshals substantial and engaging evidence to support his cyclical theory of persophilia. Persophilia’s main shortcoming has to do with the last movement of its argument, which asserts that the public sphere in Persia was not restricted to the bourgeoisie and in fact admitted subaltern classes; this claim, while prominent in the introduction, is mentioned only en passant in most chapters, and does not receive the same space and explanatory treatment enjoyed by the work’s other major ideas. In some ways the counterpart to Dabashi’s previous book—The World of Persian Literary Humanism (2012), which narrated the various stages of Persian literature’s understanding of itself in a fashion reminiscent of Hayden White’s Metahistory (1973)—Persophilia joins a wave of scholarship that sheds light on the global origins of phenomena typically considered the province of specific national traditions. Furthermore, it generates new ways of thinking about global culture that do away with tired dichotomies such as East and West, center and periphery, and tradition and modernity. What makes Persophilia an especially urgent and impressive accomplishment is that Dabashi achieves all this without advocating for parity or equivalence and without ignoring the asymmetrical power relations that underlie all encounters between cultures.”

Source: https://criticalinquiry.uchicago.edu/shaj_mathew_reviews_persophilia/

Shaj Mathew, PhD, Assistant Professor at Trinity College, is a scholar of global modernist literature. He writes about literature and film in English, Spanish, Turkish, and Persian, often in a cross-cultural key.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

All of these link to either one of my posts on twitter or a thread I made on twitter or tumblr, also my twitter is private so if you don't follow me you won't be able to access any of them, sorry.

Made this post so that I won't have to scroll for 5 minutes on my pinned post thread of threads to find what I'm looking for, and for people (who I narcissistically believe exist) that actually want to access these thoughts of mine.

Collection of threads where I annotate books/articles I'm reading

In-Progress books

"Compromised Campus: The Collaboration of Universities with the Intelligence Community, 1945-1955" by Sigmund Diamond

Hinterland: America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict by Phil A. Neel (2018)

"The Wretched of the Earth" by Frantz Fanon

"Jesus: A Life in Class Conflict" by James Crossley and Robert J. Myles

"The New Spirit of Capitalism" (New Edition) by Boltanski and Chiapello

"Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else)" by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò

"An Antonio Gramsci Reader: Selected Writings, 1916-1935", Edited by David Forgacs

"Sex Among Allies" by Katherine Moon

"The Chinese in America : A Narrative History" by Iris Chang

"Caliban And The Witch" by Silvia Federicci

"Riding the Wave: Sweden's Integration into the Imperialist World System" by Torkil Lauesen (anti-sw*den aktion)

"Sinologism: An alternative to Orientalism and postcolonialism" by Ming Dong Gu (Don't agree at ALL with the author's assessment that China has not been colonized. Not sure when I'll pick this book back up.)

"Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism" by Kwame Nkrumah (No offense but this is kind of dry but I do intend to finish it)

"The Roots of American Individualism: Political Myth in the Age of Jackson" by Alex Zakaras (Do look forward to digging into this one whenever my interest in the topic peaks)

"Model-Minority Imperialism" by Victor Bascara (not really liking so far but I just started)

"Atrocity Fabrication and Its Consequences: "How Fake news Shapes World Order" by A.B. Abrams

Completed books/articles/films

On Zionist Literature by Ghassan Kanafani [COMPLETED]

Zionist Colonialism in Palestine by Dr. Fayez Sayegh [COMPLETED] (short and sweet only 72 pages you should read it)

How to Blow Up a Pipeline by Andreas Malm [COMPLETED]

The Jakarta Method by Vincent Bevins [COMPLETED]

The Women Outside [COMPLETED]

"Why Not Genocide? Anti-Chinese Violence in Aceh, 1965-1966" by Jess Melvin [COMPLETED]

"American Exception: Empire and the Deep State" by Aaron Good [COMPLETED]

"The Case of The Gang of Four" by Chi Hsin [COMPLETED]

"Surveillance Valley: the Secret Military History of the Internet" by Yasha Levine [COMPLETED]

"The Apprentice's Sorcerer: Liberal Tradition and Fascism" by Ishay Landa [COMPLETED]

"Maoism: A Critique From The Left", edited by Prasenjit Bose [COMPLETED]

“They Looked Askance”: American Indians and Chinese in the Nineteenth Century U.S. West [COMPLETED]

"Inventing Reality" by Michael Parenti [COMPLETED]

Collection of threads/posts of hot takes

Specifically China-related

Thread on the roots of sinophobia

Thread on the Chinese coolie slave trade

Displacement of yellow peril tropes onto China

"Han Supremacy" vs. White Supremacy

Anti-China sentiment in the Soviet Union

Snobbish/arrogant Chinese

Why are westerners so obsessed with the governance of China?!?!?

(This happens for most Asians but this thread is specifically for China) The need to make China and Chinese people into a monolith

General Racism/Orientalism

Deep Racism

Fetishism of colonial frailty

Scholarship and imperialism

Orientalist Realism

Observation: propagandists act like paparazzi

On the destruction of the orient

Similarly, on the shielding of genocidal hatred of the orient

Orientalist fascination

Potential psychological roots of orientalist/sinophobic realism

Demonizing Asian leaders to the point where they aren't seen as human beings that live in space and time

I later call this "orientalist unreality"

Miscellaneous

Imperfect mothers

Collection of threads on the devaluation of artists

Another thread on the devaluation of artists

Yet another thread on the devaluation of artists

THREE threads on the western urge to consume snuff films of Chinese workers, color coded links to help you decipher between the different links: thread 1, comparison with lynching postcards and murderabilia from Abu Ghraib; thread 2; thread 3 on how this is a form of catharsis for the insecure white westerner.

Tumblr Writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indian Stock market

As an AI language model, I don't have my own opinion, but I can give you some facts you can use to write your own article about the Indian stock market. Here they are:

The Indian stock market is the oldest in Asia, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century when the Bombay Stock Exchange was established in 1854. Today, India boasts of two major stock exchanges, namely the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) and the National Stock Exchange (NSE).

The BSE is the oldest stock exchange in Asia and the first-ever stock exchange to be set up in India. It is also the largest, with more than 5,000 listed companies, and the site of the Sensex and BSE-100 indices.

The NSE, on the other hand, is the largest stock exchange in India by trading volume and market capitalization. It is the site of the NIFTY 50 index, which is widely regarded as a barometer of India's economic health.

The Indian stock market has come a long way since its early days, with the market capitalization of all listed companies rising from just INR 125 billion in 1980 to more than INR 200 trillion today. The Indian stock market has also been able to weather several economic storms, including the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and the global financial crisis of 2008.

The Indian stock market is also home to some of the world's largest companies, including Tata Consultancy Services, Infosys, and Reliance Industries. These companies have helped put India on the global business map and have contributed significantly to the country's economic growth.

In recent years, the Indian stock market has also been the site of several major reforms, including the introduction of electronic trading, the dematerialization of shares, and the move towards a more investor-friendly regulatory environment.

In conclusion, the Indian stock market is a vital part of the country's economy and a driving force behind its growth. Despite facing several challenges in the past, it has emerged stronger and more resilient, and today, it is regarded as one of the most dynamic and exciting stock markets in the world.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Photograph Courtesy the Author

At Least We Can Give Thanks For a Tree! Visiting The Largest Known White Pine.

— By Bill McKibben | Thursday November 23, 2023 (Thanksgiving Day)

As far as the climate (and, truthfully, much else) is concerned, 2023 has felt like one nasty jack-in-the-box moment after another; there have been a record number of billion-dollar natural disasters in the United States and much worse in the rest of the world. That may explain why I was so pleased a few months ago to read a short article in a Syracuse newspaper about something both unexpected and quite unreservedly lovely: this past July, in the remote Moose River Plains Wild Forest, in the Adirondacks, a young botanist named Erik Danielson found the largest Eastern white pine known to exist. Indeed, it is the largest tree of any kind known in that great wilderness, and ever since I read about it I’d been hoping he might be persuaded to take me for a look. Earlier this month, with a dusting of snow on the ground, he led a small group of enthusiasts on a two-hour bushwhack into the forest.

Danielson, aged thirty-three, is a self-taught botanist who works for the Western New York Land Conservancy, helping to, among other things, identify rare and endangered plant communities. “I’m particularly interested in mosses and liverworts,” he said, and, indeed, we’d barely left the dirt road between Indian Lake and Inlet, New York, before he was bent over a carpet of green. But, in his spare time, Danielson is a big-tree hunter, at work for the Gathering Growth Foundation, on a book about the big trees of New York. He’s part of a small band that has systematically sought out the patches of old-growth forest that were left across the East after the rapacious logging of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. I’ve known some of these sleuths for years—I spent a pleasant day a quarter century ago with one of Danielson’s mentors, another autodidact tree-lover named Bob Leverett, measuring white pines in a state park in the Berkshires. I’ve visited forest patches in the Carolinas, Vermont, and New Hampshire, but much of the remaining Eastern old growth is confined to the Adirondacks, the vast and sparsely populated quarter of New York that rises north of Saratoga, south of Quebec, and between the Mohawk and St. Lawrence Rivers, Lake Champlain, and Lake Ontario. Though the region is high and cold, with a short growing season, it’s also protected and empty, as long as you stay away from the scenic High Peaks around Lake Placid. I’ve often wandered there for days on end seeing no one.

Danielson was alerted to this particular corner of the Adirondacks by a hunter, Matt Kane, who posted a picture of a giant white pine on a Facebook group this year. Kane had been researching the logging history of the area, which came into state hands in the last decades of the nineteenth century, when it was still largely virgin forest. In 1950, a huge storm—still known as “the big blowdown”—toppled most of the trees there, and though the area was officially protected wilderness, the state allowed a controversial “salvage logging” of downed trees. For the first half of the hike, we followed, in places, an overgrown former logging road. Danielson has tools that his predecessors lacked, most notably lidar scans—basically, a Light Detection and Ranging aircraft pulses a laser down at the earth, measuring distances so accurately that it can build a 3-D picture of any area. “I was processing the canopy height model, and you could see that there had to be trees that were a hundred and forty to a hundred and sixty feet tall,” Danielson said. “In the Adirondacks, that’s very tall. And what made it really exciting was that it was a large area—it looked like five hundred or five hundred and fifty acres. Usually what you find are very small clusters”— such as the eight-acre Elder’s Grove, near Paul Smith’s College, where the state’s onetime tallest pine, Tree 103, fell in 2021.

Sometimes, as with the Elder’s Grove pine, these giant trees are situated conveniently near a road. Not in this case. We clambered along the remains of the logging road until we came to a sizable brook; you could plot a theoretical course across the rocks, but, as is often the case, theory succumbed to practice, and I slipped and got my boots wet (thank science for Gore-Tex). Across the brook, the forest began to deepen, and so did Danielson’s story (though it gave way at regular intervals to short seminars on bronze grape fern, which comes in two forms, and Northeastern sedge, “which looks a lot like yellow sedge except for some details”). He was describing his July expedition to us. On the first day, he found a very big white pine, but barely had time to catalogue it. “It felt so remote,” he said. “Usually, there are some signs of hunters, but here I didn’t even see a beer can.” He hit on a small brook, and followed it up through a quiet forest, scrambling across giant deadfalls—“nurse logs” sprouting hundreds of seedlings. “I was in a kind of ecstatic state, especially after I saw that waterfall over there,” he said. “Then I glimpsed an extra-large trunk through the trees and, as I got closer, it wasn’t getting any smaller.” Foresters, charmingly, measure the size of trees by D.B.H., or diameter at breast height, which is calculated from the circumference. He added, “When I wrapped my tape around it, it was 16.39 feet”—one of the largest ever measured for a white pine. (This tree’s D.B.H. is more than five feet.) But base circumference does not make a big tree—indeed, most really wide white pines are comparatively squat. “Looking up at this one, though, I could tell it was tall,” Danielson said. He crossed a gully to a small glade where he could get a clear view of the crown and, using a hypsometer, measured the tree’s height at a hundred and fifty-one feet and six inches.

That’s not the tallest pine we know about—last year, Danielson, not surprisingly, had measured the post-Tree 103 New York State height champion, on the other side of the Adirondacks, near Lake George, at a hundred and seventy-four feet. But many tall trees, including that one, are relatively skinny. This Moose River Plains pine, which he named Bigfoot, is a solid pole heading up into the sky. He could tell that, even at eighty feet, it was still forty inches in diameter, and he was able to conservatively estimate its volume (of the trunk and the main branches) at fourteen hundred and fifty cubic feet—reportedly, a record for the species. Indeed, Danielson says there are fewer than a dozen known, living, and verifiable specimens of white pine larger than a thousand cubic feet.

There’s enormous practical value in a big tree—new research makes it clear that they sequester vast amounts of carbon, and that letting big old trees grow is an even more effective way to draw down greenhouse gases than planting new ones. But the impractical value is likely larger; to be in the presence of a giant is for some reason calming—the air felt tranquil here, the sunlight scattered, the wind stilled. And it was somehow hopeful to think of what the tree had lived through in what Danielson says must be at least three centuries of life (it hasn’t been cored yet, and probably won’t be) and of what it might yet witness. Among many other things, that tally includes the Civil War, a trauma that exceeds even our current discontents. As it happens, one of the people on the hike was an old friend, Aaron Mair, who was the first African American president of the Sierra Club and now works with the Adirondack Council, the region’s premier conservation group. This past summer, Mair oversaw the first rendition of the Timbuctoo Institute—which draws its name from the settlement established for free Black men and their families outside Lake Placid, near John Brown’s homestead—bringing students of color from New York City to the Adirondacks to work with botanists, wildlife experts, and other conservation professionals. “It was a huge success,” Mair said. “I’ve got hundreds of kids who want to come next year, and they are going to be rangers, biologists, you name it.” Often, even amid the traumas of the moment, the seeds of what comes next are growing; sometimes they grow into something very mighty indeed. ♦

#Ecology | Conservation | Trees 🌴 🌲 🌳 | New York#Climate Change | Adirondacks#Largest Known White Pine 🌲#Bill McKibben#The New Yorker

0 notes

Text

Top Home Decor Ideas in 2023

The calling of inside plan has been an outcome of the improvement of society and the perplexing design that has come about because of the advancement of modern cycles. The quest for powerful utilization of room, client prosperity and practical plan has added to the improvement of the contemporary inside plan calling. The calling of inside plan is discrete and unmistakable from the job of inside decorator, a term generally utilized in the US; the term is more uncommon in the UK, where the calling of inside plan is as yet unregulated and in this way, rigorously talking, not yet formally a calling. In antiquated India, engineers would likewise work as inside creators. This should be visible from the references of Vishwakarma the planner — one of the divine beings in Indian folklore. In these planners' plan of seventeenth century Indian homes, figures portraying old texts and occasions are seen inside the castles, while during the bygone eras wall workmanship compositions were a typical component of royal residence like manors in India normally known as havelis. While most conventional home decor ideas have been crushed to clear a path to current structures, there are still around 2000 havelis in the Shekhawati locale of Rajashtan that show wall workmanship compositions. In old Egypt, "soul houses" (or models of houses) were set in burial chambers as containers for food contributions. From these, it is feasible to recognize insights regarding the inside plan of various homes all through the different Egyptian administrations, like changes in ventilation, porticoes, sections, loggias, windows, and entryways. Recreated Roman triclinium or lounge area, with three klinai or couchesPainting inside walls has existed for somewhere around 5,000 years, with models found as far north as the Ness of Brodgar, as have templated insides, as found in the related Skara Brae settlement. It was the Greeks, and later Romans who added co-ordinated, beautiful mosaics floors, and templated shower houses, shops, common workplaces, Castra (strongholds) and sanctuary, insides, in the principal centuries BC. With specific societies committed to creating inside enhancement, and conventional furnishings, in structures built to structures characterized by Roman modelers, like Vitruvius: De architectura, libri decem (The Ten Books on Engineering). All through the seventeenth and eighteenth hundred years and into the mid nineteenth hundred years, inside enrichment was the worry of the home decorator ideas or a utilized upholsterer or specialist who might prompt on the creative style for an inside space. Planners would likewise utilize skilled workers or craftsmans to finish inside plan for their structures. By the turn of the twentieth 100 years, beginner counselors and distributions were progressively difficult the restraining infrastructure that the enormous retail organizations had on inside plan. English women's activist writer Mary Haweis composed a progression of generally perused papers during the 1880s in which she disparaged the energy with which yearning working class individuals outfitted their homes as per the unbending models proposed to them by the retailers. She pushed the singular reception of a specific style, customized to the singular requirements and inclinations of the client: "Perhaps of my deepest feeling, and quite possibly the earliest ordinance of good taste, is that our homes, similar to the fish's shell and the bird's home, should address our singular taste and propensities. For more details please visit here https://www.elledecor.com/design-decorate/

0 notes

Text

cuisinecalls

Cuisine differs across India’s diverse regions as a result of variation in local culture, geographical location (proximity to sea, desert, or mountains), and economics. It also varies seasonally, depending on which fruits and vegetables are ripe.

Arunachal Pradesh

The staple meals of Arunachal Pradesh is rice, in conjunction with fish, meat, and leaf veggies. Native tribes of Arunachal are meat eaters and use fish, eggs, beef, chicken, pork, and mutton to make their dishes.

Many styles of rice are used. Boiled rice desserts wrapped in leaves are a famous snack. Thukpa is a form of noodle soup not unusualplace a few of the Monpa tribe of the vicinity.

Lettuce is the maximum not unusualplace vegetable, commonly organized via way of means of boiling with ginger, coriander, and inexperienced chillies.

Apong or rice beer crafted from fermented rice or millet is a famous beverage in Arunachal Pradesh and is fed on as a clean drink.

Assam

Assamese delicacies is a combination of various indigenous styles, with sizable nearby version and a few outside influences. Although it’s miles acknowledged for its confined use of spices, Assamese delicacies has robust flavours from its use of endemic herbs, fruits, and veggies served sparkling, dried, or fermented.

Rice is the staple meals object and a large sort of endemic rice varieties, together with numerous styles of sticky rice are part of the delicacies in Assam. Fish, usually freshwater varieties, are extensively eaten. Other non-vegetarian objects consist of chicken, duck, squab, snails, silkworms, insects, goat, pork, venison, turtle, screen lizard, etc.

The vicinity’s delicacies entails easy cooking processes, basically barbecuing, steaming, or boiling. Bhuna, the mild frying of spices earlier than the addition of the principle ingredients, usually not unusualplace in Indian cooking, is absent withinside the delicacies of Assam.

A conventional meal in Assam starts offevolved with a khar, a category of dishes named after the principle element and ends with a tenga, a bitter dish. Homebrewed rice beer or rice wine is served earlier than a meal. The meals is commonly served in bell metallic utensils.Paan, the exercise of chewing betel nut, usually concludes a meal

Bengal

Mughal delicacies is a commonplace influencer withinside the Bengali palate, and has brought Persian and Islamic meals to the vicinity, in addition to some of extra difficult strategies of getting ready meals, like marination the usage of ghee. Fish, meat, rice, milk, and sugar all play important components in Bengali delicacies.

Bengali delicacies may be subdivided into 4 special styles of dishes, charbya , or meals this is chewed, inclusive of rice or fish; choṣya, or meals this is sucked, inclusive of ambal and tak; lehya , or meals which can be intended to be licked, like chuttney; and peya , which incorporates drinks, in particular milk.During the nineteenth century, many Odia-speakme chefs have been hired in Bengal,[50] which brought about the switch of numerous meals objects among the 2 regions. Bengali delicacies is the most effective historically advanced multi-path culture from the Indian subcontinent this is analogous in shape to the cutting-edge provider à los angeles russe fashion of French delicacies, with meals served path-smart instead of all at once.

Bengali delicacies differs in keeping with nearby tastes, inclusive of the emphasis on the usage of chilli pepper withinside the Chittagong district of Bangladesh However, throughout all its varieties, there may be primary use of mustard oil in conjunction with huge quantities of spices.

The delicacies is understood for diffused flavours with an emphasis on fish, meat, veggies, lentils, and rice. Bread is likewise a not unusualplace dish in Bengali delicacies, especially a deep-fried model known as luchi is famous. Fresh aquatic fish is certainly considered one among its maximum unique features; Bengalis put together fish in lots of ways, inclusive of steaming, braising, or stewing in veggies and sauces primarily based totally on coconut milk or mustard.

East Bengali meals, which has a excessive presence in West Bengal and Bangladesh, is plenty spicier than the West Bengali delicacies, and has a tendency to apply excessive quantities of chilli, and is one of the spiciest cuisines in India and the World.

Shondesh and Rashogolla are famous dishes product of sweetened, finely floor sparkling cheese. For the latter, West Bengal and neighboring Odisha each declare to be the beginning of dessert. Each country additionally has a geographical indication for his or her nearby sort of rasgulla.

The delicacies is likewise located withinside the country of Tripura and the Barak Valley of Assam.

Bihar

Bihari delicacies can also additionally consist of litti chokha, a baked salted wheat-flour cake packed with sattu (baked chickpea flour) and a few unique spices, that is served with baigan bharta, product of roasted eggplant (brinjal) and tomatoes.

Among meat dishes, meat saalanis a famous dish product of mutton or goat curry with cubed potatoes in garam masala.

Dalpuri is any other famous dish in Bihar. It is salted wheat-flour bread, packed with boiled, crushed, and fried gram pulses.

Malpua is a famous candy dish of Bihar, organized via way of means of a combination of maida, milk, bananas, cashew nuts, peanuts, raisins, sugar, water, and inexperienced cardamom. Another high-quality candy dish of Bihar is balushahi, which is ready via way of means of a mainly dealt with aggregate of maida and sugar in conjunction with ghee, and the opposite global well-known candy, khaja is crafted from flour, vegetable fat, and sugar, that is in particular utilized in weddings and different events. Silao close to Nalanda is well-known for its production.

During the pageant of Chhath, thekua, a candy dish product of ghee, jaggery, and whole-meal flour, flavoured with aniseed, is made.

Other meals objects which can be pretty distinguished in Bihar are, Pittha, Aaloo Bhujiya, Reshmi Kebab, Palwal ki mithai, and Puri Sabzi.

Chandigarh

Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab and Haryana is a town of 20th-century beginning with a worldly meals way of life in particular related to North Indian delicacies. People experience home-made recipes inclusive of paratha, particularly at breakfast, and different Punjabi meals like roti that is crafted from wheat, sweetcorn, or different glutenous flour with cooked veggies or beans. Sarson da saag and dal makhani are famous dishes amongst others.Popular snacks consist of gol gappa (called panipuri in different places). It includes a round, hole puri, fried crisp and packed with a combination of flavoured water, boiled and cubed potatoes, bengal gram beans, etc.

Chhattisgarh

Chhattisgarh delicacies is specific in nature and now no longer located withinside the relaxation of India, even though the staple meals is rice, like in plenty of the country. Many Chhattisgarhi human beings drink liquor brewed from the mahuwa flower palm wine (tadi in rural areas). Chhattisgarhi cuisines varies as in step with unique events and fairs like Thethari and Khurmi, fara, gulgule bhajiya, chausela, chila, aaersa are organized in nearby fairs.[65] The tribal human beings of the Bastar vicinity of Chhattisgarh devour ancestral dishes inclusive of mushrooms, bamboo pickle, bamboo veggies, etc.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 1 Blog Post:

Hi everyone,

This week, I watched the Virtual AHA panel about the Future Directions in Research and Training for Digital History. The panel started with Zoe Genevieve Leblanc, a Ditiagal humanities professor at Princeton University. She explained the state of Digital History between the European and American perspectives on the use and need for the field of History. She started her presentation with a post that reads that Computational History is dead. She was trying to make the point that, as historians, we need to restructure how we display and collect data to show our work in the world. Zoe Genevieve Leblanc shows on the next few slides that the field of historians in the job market has decreased to the point that historians need to reinvent Digital History to make the value field to society again. If historians refuse to adapt and evolve in the 21st century, we will see a collapse in the area. A significant question while watching the panel is, what are the Future Directions in Research and Training for Digital History? The answer is that historians need to create and use applications and databases to make a visible image that shows the data that these scholars are researching. Without Universities teaching their students to work in the Digital age in the history field, we will see a steady decline in the field, however; if Universities start creating programs mandatory for future historians to take, we will see an uptick in job opportunities for history majors that are not a PhD. Their insights track with the scholarship featured in Current Research in Digital History is to find Digital History research that serves as the base for future Digital History. Also, we need to have the History departments of the Universities promote better Digital History scholarships for future and current research in the field. Overall, the panel dives deep into the problems that come with the change in how historians from the 20th and early 2000s conducted and displayed their research to more digital and interactive exhibits that the public and future historians can use for the next generation of Digital History. I have chosen three articles to show how historians use Digital programs and illuminations to display the data points they have researched throughout their articles. The first article I read was Language Borrowing Among Indian Treaties, and the author is Joshua Catalano. He uses data mapping and graphing visualization to show the wording of treaties with the native Americans from the 1770s to the 1880s. Joshua Catalano also uses data mapping and graphing visualization to deliver similar langue that each treaty had with different groups of Native Americans during this timeframe to see how the colonizers changed the language of the treaties for the other group's situations during the timeframe. This research can help show the political changes in the Americans and the policies of how the United States interacts with the Native Americans. While Joshua Catalano used digital programs to elevate his research, I will use the article, A Nested Topic Model of Britain's Debates over Landed Property in the Nineteenth Century, to show a different use of digital applications to show their finding to the public. The authors Jo Guldi and Benjamin Williams's research is about how government and land interact in nineteenth-century Britain. The digital application shows the relationship between the article topics and the keywords found in the articles they researched for their study. The style of applications that they used to display this data is Topic modeling because they take the topic and dive deeper into the subject of an article or paper that has si a language and world across their study. In comparison, these two articles show different versions of how historians display their research for the public. The last article that I will use to show examples of how historians use a digital application to conduct their research is called, The Political and Economic Geography of SNCC's Friends Network; David S. Busch writes about how the SNNCC Network reaches the public from different economic classes across the United States. He uses GIS mapping to show the census of the people with where the types were located and which part of the country these people are located. Also, he shows where the SNCC Network broadcasts in the United States. Using this type of mapping with the GIS and SNCC Network broadcasts map to show that the show truly reaches all parts of the United States and the SNCC Network broadcasts were not for a particular economic class of people. Overall, using digital applications to display their information helps the public understand the importance of these studies and supports the future of historians to grow the field with the new application that the 21st century allows.

0 notes

Text

Yes, it is critical to acknowledge the centrality of Britain to the world economy in order to understand how Chinese and Indian tea fitted into it. [...] Asian tea relied on forms of employment [...] such as independent family farms in China and indentured ‘coolies’ in India. [...] It would be very difficult to explain how and why Asian tea became driven by the modern dynamics of accumulation then, unless we connect China and India to the broader global division of labor, centered on the most cutting-edge industrial sectors in the north Atlantic. [...] But I also wish to reframe the idea of British capital as “protagonist,” because when we think about capital, agency is a weird thing. [...] Nothing about accumulation is inherently loyal to this or that region, though it has been concentrated in certain sites, such as nineteenth-century Britain or twentieth-century US, and it has been territorialized by nationalist institutions. Thus, although British firms drove the Asian tea trade at first, by the twentieth century Indian and Chinese nationalists alike protested British capital [...].

Most economic histories were focused on whether other countries could ever develop into nineteenth-century England. For labor historians, Mike Davis recently wrote, the “classical proletariat” was the working classes of the North Atlantic from 1838-1921. These modular assumptions jump out when you flip through the classics of Asian economic and labor history, almost always focused on some sort of textile industry (silk, cotton, jute) and in cities such as Shanghai, Osaka, Bombay, Calcutta. By contrast, I was really inspired by a field pioneered by South Asia scholars known as “global labor history” — especially the work of Jairus Banaji — which has been critical of the centrality of urban industry in economic history. Instead, these scholars reconsider labor in light of our current world of late capitalism, including transportation workers, agrarian families, servants, and unfree and coerced labor. These activities have enabled global capitalism to function smoothly for centuries but were overlooked because they did not share the spectacular novelty of the steam-powered factories of urban Europe, US, and Japan.

As far as how tea production worked: in simple terms, Chinese tea was a segmented trade and Indian tea was centralized in plantations known as ‘tea gardens.’ The Chinese trade relied on independent family farms, workshops in market towns, and porters ferrying tea to the coastal ports: Guangzhou (Canton) then later Fuzhou and Shanghai. By contrast, British officials and planters built Indian tea from scratch in Assam, which had not been nearly as commercialized as coastal China or Bengal. They first tried to replicate the ‘natural’ Chinese model of local agriculture and trade, but frustrated British planters ultimately decided to undertake all of the tasks themselves, from clearing the land to packaging the finished leaves. [...] Indian tea was championed as futuristic and mechanized. [...]

In India [...] the tea industry’s penal labor contract became one of the original cause célèbres of the nationalist movement in the 1880s. The plantations later became a site for strikes and hartals, the most famous occurring in the Chargola Valley in 1921. But even though tea workers chanted, “Gandhi Maharaj ki jai” at the time, Gandhi himself had allegedly visited Assam and declined to see the workers, meeting instead with British planters to assure them they were safe. While Indian nationalists had politicized indenture in Assam tea, their main complaint was the racialized split between British capital and Indian labor. Their remedy was not to liquidate the tea gardens but to diversify ownership over them. The cause of labor was subordinated to the nationalist struggle.

---

Words of Andrew B. Liu. As interviewed by Mark Frazier. Transcript published as “Andrew B. Liu - Tea War: A History of Capitalism in China and India.” Published online by India China Institute. 23 March 2020. [Some paragraph breaks and contractions added by me.]

72 notes

·

View notes

Link

Nineteenth century Indian model of Indian temples carved and constructed out of pith. Pith is found in the central cylinder of tissue found inside the stem of most flowering plants. This has a glass case that sits on its wooden base.

0 notes

Photo

Godmonster of Indian Flats

If I had a dollar for every movie I’ve seen about a bloodthirsty mutant sheep, I would have... two dollars.

I was entirely willing to feature Godmonster of Indian Flats based on its strangeness alone, but it does have one connection to MST3K in that actress Peggy Browne was also in Avalanche. Another performer here, Kerrigan Prescott, also had a part in previous Episode that Never Was Fiend Without a Face, so hey, close enough!

Dr. Clemens and his assistant Mariposa discover a mutant lamb on Eddie the Rancher’s sheep farm, and take it up to a secret lab at Indian Flats for study. This seems somewhat outside of Clemens’ claimed purview as an anthropologist, but whatever, I’m just here to watch the movies. While the monster grows to maturity in a tank, the mayor of a local tourist town, Mr. Silverdale, is refusing to sell land to a Mr. Barnstable, who is interested in the mining rights. We soon get the idea that Silverdale is less interested in tourism than he is in having his own private Wild West LARP, and the townsfolk have an almost cult-like reverence for him. Eventually, their increasingly violent attempts to run Barnstable out of town cross paths with Dr. Clemens’ pet mutant, and all hell breaks loose!

Well, maybe not all hell. This movie hasn’t got the money for all hell. Rest assured, though, that they unleash all the hell they could afford.

The hell in question takes the form of a lumpy hunchbacked sheep creature with a rubbery sock puppet head, one long dangling arm, and a huge Kim Kardashian ass. It interrupts a picnic, and blows up a gas station by knocking over a pump with its bubble butt. It may or may not understand English, and it breathes poisonous gas when injured. The puppet is pretty weird and scary-looking in the darkness of Clemens' secret lab, but out in the full light of day it is ridiculous.

Any movie with a mutant sheep monster is going to be weird, and the monster is the weirdest thing in the movie, but make no mistake – Godmonster of Indian Flats sans monster would still be a weird fucking movie. The other story going on here, Silverdale vs Barnstable, is thoroughly bizarre in itself.

Apparently it's not enough for Silverdale and the townspeople to simply refuse to sell Barnstable their mining rights. Instead, they have to totally ruin his career and both his physical and mental health! First of all, they invite him to their 'Bonanza Days' and have him take part in a shooting contest, where the whole town conspires to make it look like he accidentally shot the sheriff's dog. Then they hold a funeral for the dog as if it were a person. The whole time the dog is fine – it was just playing dead, and afterwards the sheriff sends it to live with a friend.

When Barnstable still doesn't leave town after this, Silverdale's toady Phil whacks him over the head with a bottle, then shoots himself in the shoulder and puts the gun in the unconscious man's hand. Barnstable wakes up in jail and demands a lawyer, but everybody ignores him. Eddie and Mariposa help him escape, and the sheriff then forms a posse to hunt him down and lynch him! At the end of the movie Silverdale triumphantly tells Barnstable that he's going to lose his job because his boss is embarrassed by all these goings-on. At this point Barnstable also has a cracked skull and a broken arm. He's a PTSD-ridden shell of a man and yet Silverdale is still yelling “I've beaten you, Barnstable!” as the end credits roll.

All of this might become a little less weird (but way more horrible) when I mention that Barnstable is the only black character with dialogue. And yet, none of it is ever overtly framed as racist. Nobody ever uses a slur – in fact, Barnstable's race is never once referenced in dialogue, not even obliquely. You could cast a white actor in this part and nothing would have to be changed. What Barnstable seems to represent, and what Silverdale and the townspeople claim to be fighting against (Silverdale declares that he is 'the custodian of an era'), is decadence and capitalism, concepts traditionally associated with a white elite.

This in itself should be read as a commentary on race. It's notable that Barnstable is playing by white rules. He's a smooth businessman representing the interests of his presumably white boss. When Silverdale invites him to Bonanza Days, he is happy to step into that role, too. He dresses the part and takes up the six-shooter, and does a pretty good job with it. Barnstable is a 'model minority' figure, a black man with the trappings of white success... and in spite of that, he is still abused. Hard as he tries to fit into the white people's world, he is not welcome there.

I don't think that's actually what Barnstable is supposed to represent to the viewer, however. The people of this town are described in the opening as 'living in the past' and we see that they're very dedicated to it. Silverdale dresses the part of a nineteenth century gentleman even when he's at home. Everybody dresses up in period costumes for occasions like parties and church, and the town's status as a tourist attraction requires many people to play such a role full-time. There's a dark underbelly to this quaint little world, as we see in the opening when a barmaid steals Eddie's casino winnings, but even that fits their chosen period.

Barnstable intrudes into this world as a representative of modernity and reality. If you're paying attention, you soon realize that the 'past' the townsfolk are living in isn't like the real past at all. The real history of this little mining town would have involved filthy, back-breaking work in the mines, and saloons full of drunks, prostitutes, and crime. The modern town has adopted the pretty trappings of the 19th century – the clothes, the horses, and nice little shows of piety like the dog funeral – while sweeping the dirt and violence under the rug. The latter are only to be turned on outsiders.

This fantasy version of the old west is also very, very white. In the real world, history is always more diverse than we usually think it was – one of the historical figures who inspired the character the Lone Ranger, for example, was Bass Reeves, the first black US Marshall in the west. The people in Silverdale's town have no interest in that. There is not a single Native American character in the movie, and I've already mentioned the lack of other people of colour, except for a couple of background tourists. This is an essential part of throwing away the ugly parts of the past – race brings conflict, and Silverdale and his followers want none of that. Barnstable's race makes his status as an outsider all the more obvious, both visually and as a reminder that the world these people are trying to live in never really existed.

This puts Barnstable in a very strange place in this movie. He's definitely a victim, but never a hero – in fact, Godmonster of Indian Flats is yet another movie that doesn't have a hero – yet he is not a villain, either. He's just some poor bastard who wandered into a horror movie and now he can't find his way out of it.

So... what does any of this have to do with a mutant sheep monster?

I dunno. There seem to have been mutants in this area for a long time, since Clemens talks about legends of a 'mine monster' and even shows off weird fossils he's found, but how does that tie into the theme of clinging to the past? Maybe it's supposed to be about history repeating itself, since new monsters are being born just as the mines are about to re-open? I have no idea.

Does the monster die at the end? I cannot tell you. I think it dies when the truck it was caged in blows up? The movie ends with an angry mob pushing the truck over a steep slope where they dump their garbage, while Eddie, Clemens, and Mariposa try to reveal Silverdale's own land-grab scheme. This all degenerates into chaos and people tumbling down the hill and shooting each other, while Silverdale stands there yelling about how violence controls the masses and how he's beaten Barnstable. It's an ending that seems calculated to leave the audience going, “... huh?”.

Why is it a God monster? Now this, I do have a theory about. I don't think the sheep is actually the godmonster – I think the titular menace is actually Mr. Silverdale! He wields a god-like authority within the town, even when his evil scheme is apparently exposed at the end, and uses it to do monstrous things! If that's not what they were going for... then I have no idea.

I mentioned in the opening that I've seen two movies about mutant sheep monsters. The other is Black Sheep, which is one of those off-the-wall movies they make in New Zealand when they're not doing Tolkien-related stuff. Black Sheep was apparently inspired by Godmonster of Indian Flats, but it throws out the race relations stuff and runs with the 'mutant sheep' thing to make on of the most perfect dark comedies I've ever seen. I would recommend it to the strong-stomached in the same way I recommended The Valley of Gwangi to anyone disappointed by Beast of Hollow Mountain – it is everything the older film should have been but was not.

#mst3k#reviews#episodes that never were#godmonster of indian flats#70s#just fuckin weird#allow me to recommend a better movie

41 notes

·

View notes

Link

Once citizenship was equated with human dignity, its extension to all classes, professions, both sexes, all races, creeds, and locations was only a matter of time. Universal franchise, the national service, and state education for all had to follow. Moreover, once all human beings were supposed to be able to accede to the high rank of a citizen, national solidarity within the newly egalitarian political community demanded the relief of the estate of Man, a dignified material existence for all, and the eradication of the remnants of personal servitude. The state, putatively representing everybody, was prevailed upon to grant not only a modicum of wealth for most people, but also a minimum of leisure, once the exclusive temporal fief of gentlemen only, in order to enable us all to play and enjoy the benefits of culture.

For the liberal, social-democratic, and other assorted progressive heirs of the Enlightenment, then, progress meant universal citizenship—that is, a virtual equality of political condition, a virtually equal say for all in the common affairs of any given community—together with a social condition and a model of rationality that could make it possible. For some, socialism seemed to be the straightforward continuation and enlargement of the Enlightenment project; for some, like Karl Marx, the completion of the project required a revolution (doing away with the appropriation of surplus value and an end to the social division of labor). But for all of them it appeared fairly obvious that the merger of the human and the political condition was, simply, moral necessity.2

The savage nineteenth-century condemnations of bourgeois society—the common basis, for a time, of the culturally avant-garde and politically radical—stemmed from the conviction that the process, as it was, was fraudulent, and that individual liberty was not all it was cracked up to be, but not from the view, represented only by a few solitary figures, that the endeavor was worthless. It was not only Nietzsche and Dostoevsky who feared that increasing equality might transform everybody above and under the middle classes into bourgeois philistines. Progressive revolutionaries, too, wanted a New Man and a New Woman, bereft of the inner demons of repression and domination: a civic community that was at the same time the human community needed a new morality grounded in respect for the hitherto excluded.

This adventure ended in the debacle of 1914. Fascism offered the most determined response to the collapse of the Enlightenment, especially of democratic socialism and progressive social reform. Fascism, on the whole, was not conservative, even if it was counter-revolutionary: it did not re-establish hereditary aristocracy or the monarchy, despite some romantic-reactionary verbiage. But it was able to undo the key regulative (or liminal) notion of modern society, that of universal citizenship. By then, governments were thought to represent and protect everybody. National or state borders defined the difference between friend and foe; foreigners could be foes, fellow citizens could not. Pace Carl Schmitt, the legal theorist of fascism and the political theologian of the Third Reich, the sovereign could not simply decide by fiat who would be friend and who would be foe. But Schmitt was right on one fundamental point: the idea of universal citizenship contains an inherent contradiction in that the dominant institution of modern society, the nation-state, is both a universalistic and a parochial (since territorial) institution. Liberal nationalism, unlike ethnicism and fascism, is limited—if you wish, tempered—universalism. Fascism put an end to this shilly-shallying: the sovereign was judge of who does and does not belong to the civic community, and citizenship became a function of his (or its) trenchant decree.

[...]

The perilous differentiation between citizen and non-citizen is not, of course, a fascist invention. As Michael Mann points out in a pathbreaking study3, the classical expression "we the People" did not include black slaves and "red Indians" (Native Americans), and the ethnic, regional, class, and denominational definitions of "the people" have led to genocide both "out there" (in settler colonies) and within nation states (see the Armenian massacre perpetrated by modernizing Turkish nationalists) under democratic, semi-democratic, or authoritarian (but not "totalitarian") governments. If sovereignty is vested in the people, the territorial or demographic definition of what and who the people are becomes decisive. Moreover, the withdrawal of legitimacy from state socialist (communist) and revolutionary nationalist ("Third World") regimes with their mock-Enlightenment definitions of nationhood left only racial, ethnic, and confessional (or denominational) bases for a legitimate claim or title for "state-formation" (as in Yugoslavia, Czecho-Slovakia, the ex-Soviet Union, Ethiopia-Eritrea, Sudan, etc.)

Everywhere, then, from Lithuania to California, immigrant and even autochthonous minorities have become the enemy and are expected to put up with the diminution and suspension of their civic and human rights. The propensity of the European Union to weaken the nation-state and strengthen regionalism (which, by extension, might prop up the power of the center at Brussels and Strasbourg) manages to ethnicize rivalry and territorial inequality (see Northern vs. Southern Italy, Catalonia vs. Andalusia, English South East vs. Scotland, Fleming vs. Walloon Belgium, Brittany vs. Normandy). Class conflict, too, is being ethnicized and racialized, between the established and secure working class and lower middle class of the metropolis and the new immigrant of the periphery, also construed as a problem of security and crime.4 Hungarian and Serbian ethnicists pretend that the nation is wherever persons of Hungarian or Serbian origin happen to live, regardless of their citizenship, with the corollary that citizens of their nation-state who are ethnically, racially, denominationally, or culturally "alien" do not really belong to the nation.

The growing de-politicization of the concept of a nation (the shift to a cultural definition) leads to the acceptance of discrimination as "natural." This is the discourse the right intones quite openly in the parliaments and street rallies in eastern and Central Europe, in Asia, and, increasingly, in "the West." It cannot be denied that attacks against egalitarian welfare systems and affirmative action techniques everywhere have a dark racial undertone, accompanied by racist police brutality and vigilantism in many places. The link, once regarded as necessary and logical, between citizenship, equality, and territory may disappear in what the theorist of the Third Way, the formerly Marxissant sociologist Anthony Giddens, calls a society of responsible risk-takers.

[...]

Citizenship in a functional nation-state is the one safe meal ticket in the contemporary world. But such citizenship is now a privilege of the very few. The Enlightenment assimilation of citizenship to the necessary and "natural" political condition of all human beings has been reversed. Citizenship was once upon a time a privilege within nations. It is now a privilege to most persons in some nations. Citizenship is today the very exceptional privilege of the inhabitants of flourishing capitalist nation-states, while the majority of the world’s population cannot even begin to aspire to the civic condition, and has also lost the relative security of pre-state (tribe, kinship) protection.