#Marie thérèse de France

Text

Oil Painting, 1787, French.

By Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Portraying Marie Antoinette in a red velvet dress with black fur trim, with her children.

Château de Versailles.

#élisabeth vigée le brun#marie antoinette#marie Thérèse de France#Louis Charles de France#womenswear#1780s womenswear#1787#1780s#1780s painting#1780s France#red#louis Joseph of France#dress#1780s dress#royalty#ancien regime#château de versailles

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women in History Month (insp) | Week 4: Dynastic Daughters

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#women in history#women in history month challenge#my edits#mine#marie anne de bourbon-conti#princess hexiao#hanzade sultan#caroline bonaparte#marie-thérèse-charlotte de france#princess fukang#gorgô of sparta#french history#chinese history#ancient greece#17th century#18th century#19th century#11th century#6th century bc#5th century bc

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

@perioddramasource: PERIOD DRAMA APPRECIATION WEEK

Day Two: Favourite Period Drama TV - Versailles (created by Simon Mirren and David Wolstencroft)

#versailles tv#versaillesedit#perioddramaedit#perioddramaweek2023#noemie schmidt#george blagden#alexander vlahos#evan williams#anna brewster#elisa lasowalski#jessica clark#frances pooley#catherine walker#my edits#heniette d'angleterre#louis xvi#phillipe d'orléans#chevalier de lorraine#madame de montespan#marie thérèse#liselotte von der pfalz#marie louise#madam de maintenon

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pierre Balmain Haute Couture Collection Fall/Winter 1953-54.

Marie-Thérèse in a pale blue evening dress (ball gown), strapless, (Dognin fabrics)

Pierre Balmain Collection Haute Couture Automne/Hiver 1953-54.

Marie-Thérèse dans une robe du soir (robe de bal) bleue pâle, sans bretelles, (tissus Dognin)

Photo Philippe Pottier.

#haute couture#pierre balmain#french designer#french style#fashion 50s#1953-54#fall/winter#automne/hiver#dognin#philippe pottier#marie-thérèse#evening gown#robe du soir#robe de bal#ball gown#jolie madame de france

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

༄Sala de estar, en "Le Château du Champ de la Bataille"

༄El Castillo de "Champ de Bataille" fue construido en el siglo XVII por el Conde Alexandre de Créqui-Bernieulles. Este castillo está situado en la localidad de Sainte-Opportune-du-Bosc, a escasos kilómetros de Neubourg, en la Alta Normandía, en Francia. Desde 1992 pertenece al diseñador Jacques García, que lo ha restaurado y remodelado, para lograr que el aspecto del castillo se asemejara al que tenía en el siglo XVII.

#france#francia#normandía#17th century#château#campo de batalla#marie thérèse#luis xiv#elegance#elegant style#aristocracy#french aristocracy#luxurydecor#luxury

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Set Women in House of Bourbon [Black & White]

Fanart by Sweet_FXXKER

#house of bourbon#bourbon#anne of austria#maria theresa of spain#Marie Leczinska#madame de pompadour#Jeanne Antoinette Poisson Marquise de Pompadour#marie antoinette#Marie Thérèse of France#black and white drawing

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Seventeenth-century stars ?

When Paul Scarron baptized the leading lady of his profoundly provincial theatrical troupe "Mademoiselle de l'Etoile" in Le Roman Comique in 1651, we might think he was verging on irony. In fact, the word "star", meaning an actor or actress distinguished by his or her celebrity, seems to have entered English usage only in the nineteenth century and to have been borrowed by the French in the twentieth. Scarron's pairing of Mlle de l'Etoile with her partner, Le Destin, plays rather on an earlier meaning of étoile, as in Shakespeare's "a star danced and under that I was born". Both "Destin" and "Etoile" imply that fate rather than choice has determined their profession. But in fact, if not in lexicography, the "star", that is, someone notably conspicuous for professional accomplishments and celebrity, was born in France over the course of the last half of the seventeenth century.

A "star" displays some fairly obvious characteristics. Perhaps the most important one is that audiences are drawn to star performances, increasing the financial rewards for everyone involved. Another sign of stardom is when playwrights write specific roles to feature the biggest draws. In the seventeenth century, the two great star-makers were Molière and Racine. Of course, Molière primarily wrote plays that featured Molière, but he also established the stardom of his wife, Armande Béjart, with roles like the Princesse d'Elide, Psyché, Célimène, and Elmire. Racine would probably be aghast at being accused of writing star vehicles for anyone, but nonetheless he wrote for one potential star, Mlle du Parc, and one full star, Mlle Champmeslé, fashioning for them important roles that played to their strengths.

Celebrity, which mixes fame with notoriety, is another aspect of stardom. Mlle du Parc and especially Mlle Molière and Mlle Champmeslé were both famous and notorious. Mlle Du Parc, whose career as as star actress was fleeting, and who is known to history as the mistress of Racine and for her mysterious death and her supposed involvement with the poisoner La Voisin, has been the subject of two recent biographies and a film, while Mlle des Œillets, the most accomplished actress of the period, is completely forgotten. Notoriety need not rest on reality; it can be manufactured. Mlle Molière, for instance, was the subject of a vicious book accusing her of all kinds of transgression, including common prostitution, and damaging her reputation, although primarily after the fact. She, too, has been the subject of various biographies, including one fictionalized biography that features many of the accusations contained in the book. And even Ariane Mnouchkine's great biographical film Molière relies on the assumption that Armande Béjart was persistently unfaithful to her husband, although no hard evidence supports that such was the case. Mlle Champmeslé was certainly no saint; that she enjoyed relationships with men other than her husband is incontrovertible. Of the three, however, she would seem to be the one whose celebrity arose from a balance of professional accomplishments and her willing participation in the galanterie of seventeenth-century Paris.

Virginia Scott- Women on the Stage in Early Modern France: 1540-1750.

#xvii#virginia scott#women on the stage in early modern france#paul scarron#molière#jean baptiste poquelin#jean racine#marquise-thérèse du parc#marie desmares#la champmeslé#armande béjart#la voisin#alix faviot#mademoiselle des oeillets#actresses#history of theater

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

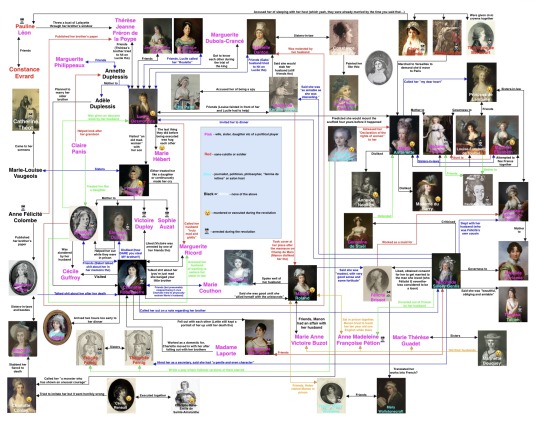

I decided to try this but for the girlies instead.

Are you sure want to click on ”keep reading”?

For Pauline Léon marrying Claire Lacombe’s host, see Liberty: the lives of six women in Revolutionary France (2006) by Lucy Moore, page 230

For Pauline Léon throwing a bust of Lafayette through Fréron’s window and being friends with Constance Evrard, see Pauline Léon, une républicaine révolutionnaire (2006) by Claude Guillon.

For Françoise Duplay’s sister visiting Catherine Théot, see Points de vue sur l’affaire Catherine Théot (1969) by Michel Eude, page 627.

For Anne Félicité Colombe publishing the papers of Marat and Fréron, see The women of Paris and their French Revolution (1998) by Dominique Godineau, page 382-383.

For the relationship between Simonne Evrard and Albertine Marat, see this post.

For Albertine Marat dissing Charlotte Robespierre, see F.V Raspail chez Albertine Marat (1911) by Albert Mathiez, page 663.

For Lucile Desmoulins predicting Marie-Antoinette would mount the scaffold, see the former’s diary from 1789.

For Lucile being friends with madame Boyer, Brune, Dubois-Crancé, Robert and Danton, calling madame Ricord’s husband ”brusque, coarse, truly mad, giddy, insane,” visiting ”an old madwoman” with madame Duplay’s son and being hit on by Danton as well as Louise Robert saying she would stab Danton, see Lucile’s diary 1792-1793.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Marie Hébert, see this post.

For the relationship between Lucile Desmoulins and Thérèse Jeanne Fréron de la Poype, and the one between Annette Duplessis and Marguerite Philippeaux, see letters cited in Camille Desmoulins and his wife: passages from the history of the dantonists (1876) page 463-464 and 464-469.

For Adèle Duplessis having been engaged to Robespierre, see this letter from Annette Duplessis to Robespierre, seemingly written April 13 1794.

For Claire Panis helping look after Horace Desmoulins, see Panis précepteur d’Horace Desmoulins (1912) by Charles Valley.

For Élisabeth Lebas being slandered by Guffroy, molested by Danton, treated like a daughter by Claire Panis, accusing Ricord of seducing her sister-in-law and being helped out in prison by Éléonore, see Le conventionnel Le Bas : d'après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve, page 108, 125-126, 139 and 140-142.

For Élisabeth Lebas being given an obscene book by Desmoulins, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre dissing Joséphine, Éléonore Duplay, madame Genlis, Roland and Ricord, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834), page 76-77, 90-91, 96-97, 109-116 and 128-129.

For Charlotte Robespierre arriving two hours early to Rosalie Jullien’s dinner, see Journal d’une Bourgeoise pendant la Révolution 1791–1793, page 345.

For Charlotte Robespierre and Françoise Duplay’s relationship, see Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 85-92 and Le conventional Le Bas: d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve (1902) page 104-105

For the relationship between Charlotte Robespierre and Victoire and Élisabeth Lebas, see this post.

For Charlotte Robespierre visiting madame Guffroy, moving in with madame Laporte and Victoire Duplay being arrested by one of Charlotte’s friends, see Charlotte Robespierre et ses amis (1961)

For Louise de Kéralio calling Etta Palm a spy, see Appel aux Françoises sur la régénération des mœurs et nécessité de l’influence des femmes dans un gouvernement libre (1791) by the latter.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 198-207

For the relationship between Madame Pétion and Manon Roland, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 158 and 244-245 as well as Lettres de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 510.

For the relationship between Madame Roland and Madame Buzot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland (1793), volume 1, page 372, volume 2, page 167 as well as this letter from Manon to her husband dated September 9 1791. For the affair between Manon and Buzot, see this post.

For Manon Roland praising Condorcet, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 2, page 14-15.

For the relationship between Manon Roland and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires de Madame Roland, volume 1, page 360.

For the relationship between Helen Maria Williams and Manon Roland, see Memoirs of the Reign of Robespierre (1795), written by the former.

For the relationship between Mary Wollstonecraft and Helena Maria Williams, see Collected letters of Mary Wollstonecraft (1979), page 226.

For Constance Charpentier painting a portrait of Louise Sébastienne Danton, see Constance Charpentier: Peintre (1767-1849), page 74.

For Olympe de Gouges writing a play with fictional versions of the Fernig sisters, see L’Entrée de Dumourier à Bruxelles ou les Vivandiers (1793) page 94-97 and 105-110.

For Olympe de Gouges calling Charlotte Corday ”a monster who has shown an unusual courage,” see a letter from the former dated July 20 1793, cited on page 204 of Marie-Olympe de Gouges: une humaniste à la fin du XVIIIe siècle (2003) by Oliver Blanc.

For Olympe de Gouges adressing her declaration to Marie-Antoinette, see Les droits de la femme: à la reine (1791) written by the former.

For Germaine de Staël defending Marie-Antoinette, see Réflexions sur le procès de la Reine par une femme (1793) by the former.

For the friendship between Madame Royale and Pauline Tourzel, see Souvernirs de quarante ans: 1789-1830: récit d’une dame de Madame la Dauphine (1861) by the latter.

For Félicité Brissot possibly translating Mary Wollstonecraft, see Who translated into French and annotated Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman? (2022) by Isabelle Bour.

For Félicité Brissot working as a maid for Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis: sur le dix-huitième siècle et sur la révolution française, volume 4, page 106.

For Reine Audu, Claire Lacombe and Théroigne de Méricourt being given civic crowns together, see Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel, September 3, 1792.

For Reine Audu taking part in the women’s march on Versailles, see Reine Audu: les légendes des journées d’octobre (1917) by Marc de Villiers.

For Marie-Antoinette calling Lamballe ”my dear heart,” see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 197, 209 and 252.

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Madame du Barry, see https://plume-dhistoire.fr/marie-antoinette-contre-la-du-barry/

For Marie-Antoinette disliking Anne de Noailles, see Correspondance inédite de Marie Antoinette, page 30.

For Louise-Élisabeth Tourzel and Lamballe being friends, see Memoirs of the Duchess de Tourzel: Governess to the Children of France during the years 1789, 1790, 1791, 1792, 1793 and 1795 volume 2, page 257-258

For Félicité de Genlis being the mistress of Louise Marie Adélaïde de Bourbon’s husband, see La duchesse d’Orléans et Madame de Genlis (1913).

For Pétion escorting Madame Genlis out of France, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis…, volume 4, page 99.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Louise de Kéralio Robert, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume, page 352-354

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Germaine de Staël, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 2, page 316-317

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théophile Fernig, see Mémoires inédits de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 300-304

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Félicité Brissot, see Mémoires inédites de Madame la comptesse de Genlis, volume 4, page 106-110, as well as this letter dated June 1783 from Félicité Brissot to Félicité Genlis.

For the relationship between Félicité de Genlis and Théresa Cabarrus, see Mémoires de Madame de Genlis: en un volume (1857) page 391.

For Félicité de Genlis inviting Lucile to dinner, see this letter from Sillery to Desmoulins dated March 3 1791.

For Marinette Bouquey hiding the husbands of madame Buzot, Pétion and Guadet, see Romances of the French Revolution (1909) by G. Lenotre, volume 2, page 304-323

Hey, don’t say I didn’t warn you!

#french revolution#frev#marie antoinette#pauline léon#claire lacombe#théroigne méricourt#reine audu#charlotte robespierre#éléonore duplay#élisabeth duplay#élisabeth lebas#lucile desmoulins#louise de kéralio#félicité de genlis#félicité brissot#mary wollstonecraft#manon roland#madame royale#charlotte corday#albertine marat#simonne evrard#catherine théot#madame élisabeth#sophie condorcet#françoise duplay#cécile renault#gabrielle danton#louise sebastien danton#theresa tallien#theresa cabarrus

173 notes

·

View notes

Text

In defense for Marie Antoinette

A long time ago following a passionate debate and good reblogs that you can easily find on Tumblr (if everyone agrees I will put the link), I had fun defending Marie Antoinette (although a fervent sympathizer about the Montagnards).As in two weeks it will be the defense of Manon Roland, I will put this ability to defend to the test by publishing what I had already written about the former queen of France. Here we go:

The problem with Marie Antoinette is that her education was often neglected, and her mother, the Great Marie Thérèse, an excellent politician, instilled in her very conservative ideas, not to mention the fact that she wanted her daughter to become a spy but without the great talent political of her mother. This will be one of the reasons why it will be a great problem when she arrives at the Court.

She won't have the necessary mental strength to face the heaviness of the protocol, and although she caused major problems initially in terms of expenditure, her frankness, unsuitable for a dauphine then a queen, and her frivolity don't help. In addition to the expenses she incurs to please her friends (notably Polignac), wanting to forget the pressure her mother puts on her, despite Louis being a good husband to her, with no children, which is a source of gossip, she decides to increasingly take refuge in Trianon, which again leads to excessive spending, not to mention new clothes. But it's important to note that once she had children, she behaved much less frivolously, more reasonably, less extravagantly, but refused to reintegrate Versailles, which she deemed as heavy and hypocritical (rightly so, but as her mother said, with privileges come duties; if she had made a concession on this side, perhaps she could have obtained less absurd protocol).

Once she had children with her husband Louis XVI, they did everything to ensure that their offspring did not have a high opinion of themselves. Just look at the fact that she wanted her children to dress equally to some of the household children and in her letters indicates that she does not want her daughter to be as arrogant as her aunts. She even tells them that since there are more and more poor people in France, they won't have gifts at a certain period. So she's not a snobbish woman.

Contrary to popular belief, Louis XVI is never influenced by his wife; in fact, she herself knows how to stay in her place as a queen consort and simply prefers to organize certain festivities. But her excessive frankness, rejection of her duties, frivolity in expenditure, and the fact that she sometimes openly shows disdain, for example, for Turgot (one of the few good financial controllers of Louis XVI) will make her the object of all vices in France and a scapegoat for all the decisions of the old Regime.

Do you know who agrees on this point? The revolutionary Saint Just himself in his writings in 1792, who immediately grasped the personality of the Queen in these terms: "Rather deceived than deceitful, rather light than perjured, entirely devoted to pleasure, she seemed to reign not in France but at Trianon."

Moreover, Joséphine de Beauharnais, who was a hundred times more spendthrift and frivolous than her, was much more loved because she took care of her image unlike Marie Antoinette. Perhaps because Marie Antoinette was more frank than her .

In the end, Marie Antoinette stole less from the coffers, so to speak, because her husband wouldn't have let her, and she herself wouldn't have wanted to. Theresia Cabarrus, who profited well from Tallien's scam, was seen as wonderful because she took care of her image. Furthermore, Marie Antoinette clearly displayed her allegiance and stuck to it until the end (although this allegiance was outdated, her mother's conservative ideas about absolute monarchy), faithful to the people she loved (she insisted on sheltering her friends, but Lamballe returned despite the queen's pleas not to do so to support her, faithful to her husband, despite the arranged marriage, because even though she insisted they leave, she didn't want to leave him alone), isn't a friend of the good day only, compared to Cabarrus, who claimed to be imbued with Enlightenment ideas, said she didn't like bloodshed, but in the end, went from one bloody person to another not out of survival (as she liked to say) but out of wealth before marrying a royalist. Yet Theresia and Beauharnais (who took part in the serious scandal during the creation of the Bank of France as a shareholder) did not receive as much criticism.

Of course, we can also understand Marie Antoinette's criticism of Necker, a proud man who is content to borrow and pretend to be more competent than he really is and stabs people in the back (he criticized Turgot but if Turgot hadn't played the "villain," Necker wouldn't have been able to borrow a penny to cover his good reputation not to mention his weather vane attitude and his false attitude as a friend of the people that Marat denounced ), although I don't understand the contempt she had for Turgot.

For her betrayal towards France, I agree with all of you , it's inexcusable, I won't go back on that. What Louis XVI did (primarily him because he was never influenced by his wife, but she also has some responsibility in this regard) is involuntary mass homicide against the French people for the return of absolute monarchy. The problem is that at that time we didn't have the necessary evidence to condemn her (although there was legitim suspicion of the truth), it was a parody and even Saint Just seemed to oppose this execution by telling Robespierre that "this act (the execution) would not benefit national sovereignty." Unfortunately, the person who said this in one of the forums, however, very educated, lost the citation from this book, so let's go cautiously, especially since if the letters had been found, I think Saint Just would have been in favor of the execution of Marie Antoinette. But as mentioned above, at least Antoinette did not betray any ideals, she was clear about that unlike Cabbarus who claimed that she rejected Tallien because of the blood in his hand but then go to Barras, said that she is attired by « les idées lumières » and go to wedding a monarchist, etc., who do not receive as much criticism. But I also understand the hatred she received from Jacques Roux, from a Momoro, and from so many others who never had luxury and found her expenses and behavior legitimately scandalous. But like everyone else outraged and shocked by the behavior of Hébert (and Pache, Chaumette, and Jacques Louis David should not be forgotten even though I like Pache and I find Chaumette unfairly maligned by their best moments it’s was not their best moments and should have died of shame for using such a method, as for Hébert and even to a lesser extent Jacques Louis David, let's not even talk about them).

At least Marie Antoinette unlike other didn’t betrayals the ideas of the revolution unlike some who claimed themself child of the revolution and then betray the revolutionnaries.

If we want to fight against the dishonest people who have blamed everything on people like Saint Just, Robespierre, Couthon, Billaud Varennes (isn't Fouché and Turreau?) we must also do the same thing even for people who are against the revolution even if I agree that the martyrdom of the upper class is tiring and that making Marie Antoinette a pure feminist and innocent icon is just as wrong (but I am here to defend her in this post).

P.S.: I know that Theresia and Joséphine did not harm people unlike their husbands and lovers at least not as much; I do not want to absolve Napoleon, Barras, Tallien; they did not need these women to do what they are reproached for, but to better situate them in relation to Marie Antoinette.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Collaborative Masterpost on Saint-Just

Primary Sources

Oeuvres complètes available online: Volume 1 and Volume 2

A few speeches

L'esprit de la révolution et de la constitution de la France (1791)

Transcription of the Fragments sur les institutions républicaines (1800) kept at the BNF by Pierre Palpant

Alain Liénard's edition and transcription of his works in Théorie politique (1976)

Some letters kept in Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan, etc. (1828)

Fragment autographe des Institutions républicaines

Une lettre autographe signée de Saint-Just, L. B. Guyton et Gillet (not his writing but still interesting)

Two files at the BNF with his writing (and other strange random stuff):

Notes et fragments autographes - NAF 24136

Fragments de manuscrits autographes, avec pièces annexes provenant de Bertrand Barère, de V. Expert et d'H. Carnot - NAF 24158

Albert Soboul's transcription of the Institutions républicaines + explanation of what's in these files at the BNF

Anne Quenneday's philological note on the manuscript by Saint Just, wrongly entitled De la Nature (NAF 12947)

Masterpost (inventory, anecdotes, etc.) - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Chronology

Chronology from Bernard Vinot's biography

Testimonies

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas on Saint-Just, as reported by David d'Angers - by frevandrest and robespapier

Élisabeth Duplay-Le Bas corrects Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des girondins (1847) - by anotherhumaninthisworld

Many testimonies by contemporaries (in French) on antoine-saint-just.fr

Representations

Everything Wrong with Saint-Just's Introductory Scene in La Révolution française (1989) - by frevandrest

On Saint-Just's strange representation of "throwing tantrums" - by saintjustitude and frevandrest

Saint-Just as "goth/emo boy"? - by needsmoreresearch, frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

Recommended Articles

Bernard Vinot:

"La révolution au village, avec Saint-Just, d'après le registre des délibérations communales de Blérancourt", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 335, Janvier-Mars 2004, p. 97-110

Alexis Philonenko:

"Réflexions sur Saint-Just et l'existence légendaire", Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale, 77e Année, No. 3, Juillet-Septembre 1972, p. 339-355

Miguel Abensour:

"Saint-Just, Les paradoxes de l'héroïsme révolutionnaire", Esprit, No. 147 (2), Février 1989, p. 60-81

"Saint-Just and the Problem of Heroism in the French Revolution", Social Research, Vol. 56, No. 1, "The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity", Spring 1989, p. 187-211

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux". Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 183, Janvier-Mars 1966, p. 1-32. (première partie)

"La philosophie politique de Saint-Just: Problématique et cadres sociaux", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 38e Année, No. 185, Juillet-Septembre 1966, p. 341-358 (suite et fin)

Louise Ampilova-Tuil, Catherine Gosselin et Anne Quennedey:

"La bibliothèque de Saint-Just: catalogue et essai d'interprétation critique", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, No. 379, Janvier-mars 2015, p. 203-222

Jean-Pierre Gross:

"Saint-Just en mission. La naissance d'un mythe", Annales historiques de la Révolution française, Année 1968, no. 191 p. 27-59

Marie-Christine Bacquès:

"Le double mythe de Saint-Just à travers ses mises en scène", Siècles, no. 23, 2006, p. 9-30

Marisa Linton:

"The man of virtue: the role of antiquity in the political trajectory of L. A. Saint-Just", French History, Volume 24, Issue 3, September 2010, p. 393–419

Misc

Saint-Just in Five Sentences - by sieclesetcieux

On Saint-Just's Personality: An Introduction - by sieclesetcieux

Pictures of Saint-Just's former school, with the original gate - by obscurehistoricalinterests

Saint-Just vs Desmoulins (the letter to d'Aubigny and other details) - by frevandrest

Saint-Just's sisters - by frevandrest

On Thérèse Gellé and Henriette Le Bas - by frevandrest

Saint-Just and Gellé being godparents - by frevandrest and robespapier

On Saint-Just "stealing" and running away to Paris and the correction house - by frevandrest and sieclesetcieux

How was/is Saint-Just pronounced - Additional commentary in French by Anne Quenneday

#saint-just#antoine saint just#saint just#to be updated#masterpost#refs#sources#frev sources#testimonials and commentaries

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685-1766)

Madame Marie-Louise-Thérèse-Victoire de France - A Água (Princess Victoire of France - The Water), Detail, 1751

São Paulo Museum of Art

#french princess#french aristocracy#aristocrat#royalty#royal#french art#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#oil painting#fine arts#europa#mediterranean#Madame Marie Louise Therese Victoire de France#allegorical art#1700s#french#france#painting#female#portrait#powdered hair#princess

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oil Painting, 1794, French.

By Marie Thérèse Vincent de Montpetit.

Portraying Mademoiselle Lange, an actress, in a blue silk dress and red ribbon.

Robert Simon.

#marie Thérèse Vincent de Montpetit#Robert Simon#mademoiselle Lange#1794#1790s#1790s painting#1790s France

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 19th century engraving depicting Marie-Thérèse Charlotte de France, the duchesse d'Angoulême

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Fürstenberg Tiara

1870s-1890s

The letter which is kept in the Fürstenberg archives, headed by Flach Mediansky & Paltscho, famous Austrian jewelers at the end of the XIX century, explains the many ways in which the extraordinary tiara can be worn. The first and most obvious one, is to wear it complete. Eleven diamond motives in the shape of a double fleur-de-lys, twenty-three pear-shaped pearls (three larger ones) are all fixed on a old-cut diamond frame. This is the way that tiara must have been worn in court by its then owner: H.S.H. the princess of Fürstenberg, née countess Irma of Schönborn Buchheim (1867-1948). Although most of their lands were located in Germany, in the south of Baden-Württemberg, the princes of Fürstenberg were princes of the Holy Roman Empire and they had received their titles from the Habsburg emperors. They also owned land in Bohemia and a very impressive palace in Vienna. Therefore, they were very much part of the Viennese high society.

The Austrian season always started in January with the New Year’s reception and ended in May with the Corpus Christie’s procession which was described by some as "God’s court ball.” Between those two dates, concerts, lavish dinners, private and official balls would take place. The most important of those events were the balls given at the Hofburg palace by the order of His Majesty Emperor Franz Joseph I. Divided in two categories: Court balls and Balls at Court. 2000 guests were invited to the Court Balls. The list would include guests from the aristocracy, but also from the political and military world. Balls at Court only included 800 guests, chosen exclusively among the higher aristocracy. The princesses of Fürstenberg were included in both lists and were also invited to opera premières and private concerts. Therefore the princesses needed quite a few tiaras, or at least a very transformable one.

In the letter, the jeweller mentions a second way to wear the tiara, simply by removing the diamond motives. This way the 23 pearls seemed to just hang among the hair. A third way, even lighter, but still impressive, was to remove the smaller pearls, leaving only the big ones. A fourth way, was to wear only the diamond motives with no pearls. There was of course a fifth way, not mentioned in the letter, to replace the pearls with other precious stones. And this is exactly what princess Irma of Fürstenberg did when she had her portrait painted by Laszlo. She replaced the central pearl with an emerald drop. The diamond motives could also be assembled to be worn as a rather impressive diamond necklace. And each diamond motive could be worn as a brooch or a hair pin.

For centuries, the Fürstenberg family had been at the very top list of the most important aristocratical families in the Habsburg Empire. The wealth and status of that family was such that in 1770, when archduchess Marie-Antoinette travelled to Versailles where she would marry the future Louis XVI of France, Donaueschingen was chosen as one of her stops. Prince Starhemberg, who was commander of the escort of the archduchess, was so amazed by the splendor of the Fürstenberg court that he wrote to Empress Marie-Thérèse, on the 3rd of May 1770:

Around three in the afternoon, we arrived at the Prince of Fürstenberg’s estate at Donaueschingen. All here is established with magnificence as if the court was that of a sovereign. All the male courtesans were wearing a very rich uniform. And the ladies, including the princess, had white silk dresses embroidered with golden lace. The Prince had all the roads of his principality rebuilt for the archduchess’ trip. It must have cost him more than 200,000 gold florins.

-Vincent Meylan

Christie’s

#tiara#necklace#fashion history#historical fashion#victorian#1870s#1880s#1890s#19th century#diamond#pearl#jewelry#austria#christies

319 notes

·

View notes

Text

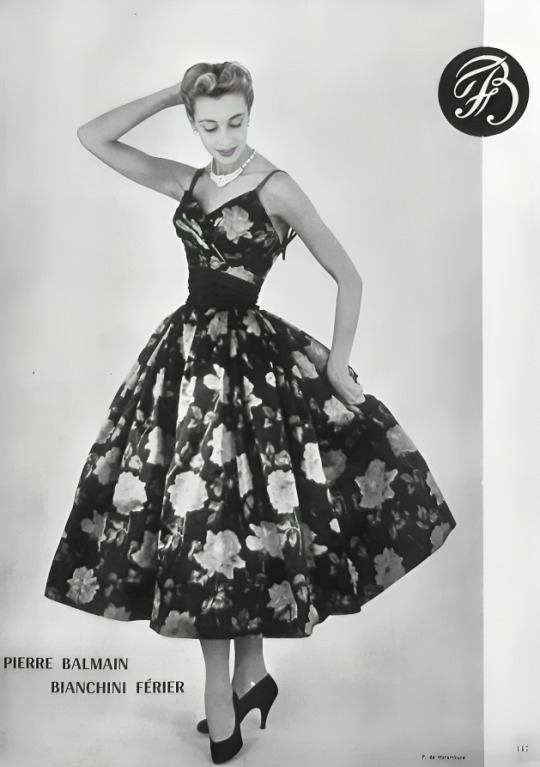

Pierre Balmain Haute Couture Collection Fall/Winter 1954-55 “Jolie Madame de France”

Marie-Thérèse wears a dress in silk taffeta printed with large red roses with green foliage on a black background (Bianchini-Férier silk),

draped belt in black taffeta.

Pierre Balmain Collection Haute Couture Automne/Hiver 1954-55 "jolie Madame de France"

Marie-thérèse porte une robe en taffetas de soie imprimé de grosses roses rouges à feuillages verts sur fond noir de (soie Bianchini-Férier),

ceinture drapée en taffetas noir.

Photo Philippe Pottier

#haute couture#pierre balmain#fashion 50s#1954-55#fall/winter#automne/hiver#bianchini-férier#cocktail dress#robe de cocktail#taffeta#printed#marie-thérèse#philippe pottier#jolie madame de france

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marie-Thérèse-Antoinette-Raphaëlle d'Espagne, Dauphine de France (1726-1746). Par Louis-Michel van Loo.

#louis michel van loo#royaume de france#maison de bourbon#bourbon espagne#infanta de españa#infantes de españa#dauphine de france#full length portrait#kingdom of spain#house of bourbon#full-length portrait

4 notes

·

View notes