#Jehan Duseigneur

Photo

Je reviens à mon projet de présenter la plupart de mes 54110 photos (nouveau compte )

2015. Une balade au Louvre-Lens

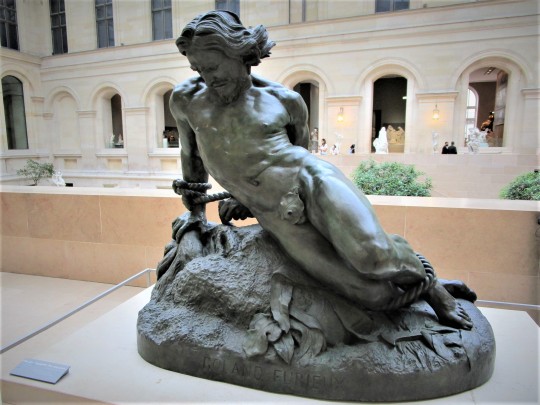

- alternés avec : Jehan Duseigneur : “Roland furieux”, 1831

- Ingres :”Roger délivre Angélique du Monstre marin”, 1819

- (les 2 autres): jardinière acajou et bronze - Châlons-sur-Marne, 1819

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Orlando Furioso by Jehan Duseigneur

Louvre Museum, Paris

#bronze sculpture#Ariosto#epic poetry#16th century#Romantic art#madness#male nude#fine art#medieval poetry

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Medallion of Theophile Gautier by Jehan DuSeigneur!!!

#I had never seen this one#only an etching#the louvre collection also has Orlando Furioso which is great imo#Theophile Gautier#Jehan Duseigneur#four people and a shoelace#petit cenacle#art art art#louvre collection

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

TFW you're looking through a bunch of cosplay photos and they actually take the time to visit Nerval's grave. And you just see his name... ;_;

(They are remembered)

#Whenever I see something about#Nerval#Gautier#Borel#Jehan DuSeigneur#They are remembered#*cries*#French Romantics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s almost Yuletide! This will be my 18th Yuletide! My first Yuletide story will be old enough to vote this year and I have some mixed feelings about that! But also I have never missed or defaulted on a Yuletide since, and I have to say I feel pretty proud of that.

I am still pretty far down the Les Misérables rabbit hole (speaking of which, it is not too late to propose programming for Barricades!), and unsurprisingly all the fandoms I'm nominating/requesting this year are set in July Monarchy France--Les Mis canon era: Petit-Cénacle RPF,

Champavert: Contes Cruelles | Champavert: Immoral Tales - Pétrus Borel, and Les Enfants du Paradis | Children of Paradise.

Petit-Cénacle RPF

The Petit-Cénacle was a French Romantic salon, slightly younger and considerably more politically radical than the Cénacle centered on Hugo and Dumas; it included painters and sculptors as well as writers and critics, and most of its members at least dabbled in both written and visual arts. Its best-known members today are Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and Pétrus Borel (the Lycanthrope)--the last two are thinly fictionalized in Les Misérables as Jean Prouvaire and Bahorel. (It's debatable how much Grantaire owes to Gautier but it's probably a nonzero amount.)

The group coalesced around Borel and Nerval as the organizers of the Battle of Hernani--a fight between Romantics and classicists at the premiere of Victor Hugo's play Hernani in 1830. Most theater productions at this time had claques--groups of paid supporters of a show or an actor, who were planted in the audience to drum up applause. For Hernani--the first Romantic work staged at the prestigious Comédie-Français, which broke classical norms so thoroughly that it no longer seems at all transgressive--Hugo and the theater management decided they were going to need more than just a claque. They recruited a few of Hugo's fans--Gautier was so star-struck he had to be physically hauled up the stairs to Hugo's apartment--to stage An Event. The fans recruited their friends. They showed up in cosplay, with the play already memorized and callback lines devised. It was basically the Rocky Horror Picture Show of its day. It almost immediately turned into an actual fight, with fists and projectiles flying. And it made Hernani the hottest ticket in Paris.

This is the group's origin story, and they pretty much spent their lives living up to it. They were every bit as extra as you would expect--Nerval allegedly walked a lobster on a leash in the Champs-Elyseés, explaining that "it knows the secrets of the deep, and it does not bark"--but they also stayed friends all their lives, often living together, supporting each other through poverty and mental illness and absurd political upheaval.

I'm nominating Pétrus Borel | Le Lycanthrope, Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and Philothée O’Neddy; you could nominate other people like Jehan Duseigneur, Celestin Nanteuil, or the Deverias, or associates of the group like Dumas and Hugo.

The Canon

Gautier's History of Romanticism covers the early days of the group and the Battle of Hernani in some detail. (There is also a 2002 French TV movie, La bataille d'Hernani, which is charming and pretty accurate; hit me up if you want a copy.)

Other than that--this crowd wrote a lot, and they're all very present in their work--even in their fiction, which is shockingly modern in a ton of ways.

For Gautier, Mademoiselle de Maupin has a lot of genderfeels, surprisingly literal landscape porn, and a fursuit sex scene in chapter two.

If you want Nerval's works in English, you might be limited to dead-tree versions, but I highly, highly recommend The Salt Smugglers, a work of metafiction that answers the question, "What if The Princess Bride had been written in 1850 specifically to troll the press censorship laws of Prince President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte?"

Borel's experimental short story collection Champavert has a new and very good English translation by Brian Stableford and is also my next fandom :D.

Champavert: Contes Immoraux | Champavert: Immoral Tales - Pétrus Borel

Last year I requested Borel RPF but I decided this book was unfanficcable. This year, I am going to have a little more faith in the Yuletide community.

Champavert, available in ebook and dead tree form, is a weird as hell little book and probably the best thing I read last year. It's an experimental short story collection from 1830. Someone on one of my Les Mis Discords described it as "a collection of gothic creepypasta, but the author is constantly clanging pots and pans together and going 'JUST IN CASE you didn't notice, the real horror was colonialism and misogyny all along and i'm very angry about it!'"

And, yeah, pretty much that, with added metafictional weirdness, intense nerding about architecture and regional languages, and the absolute delight that is Borel's righteously ebullient voice.

Borel wrote for a couple of years under the name of The Lycanthrope, and though he kills the alter ego in this book, the name stuck, and would continue to be used by friends and enemies alike all his life. Pretty much everyone who met Pétrus agreed that 1) he was just ungodly hot; 2) he was probably a werewolf, sure, that makes sense; and 3) he was definitely older than he claimed to be, possibly by centuries, possibly just immortal, who knows.

But, like I said, he kills the alter ego in this book: it begins with an introduction announcing that "Pétrus Borel" has been a pseudonym all along, that the Lycanthrope's real name is Champavert--and that the Lycanthrope is dead and these are his posthumous papers, compiled by an unnamed editor; the papers include some of Borel's actual poems and letters, published under his own name. The final story in the collection is called "Champavert, The Lycanthrope," and is situated as an autobiographical story, following a collection of fictional tales--which share thematic elements and, in the frame of the book, start to look like "Champavert"'s attempts to use fiction to come to terms with events of his own life.

And that's probably an oversimplification; this is a dense little book and it's doing a lot.

The subtitle is Contes Immoraux. It's part of a genre of "contes cruelles" (and, content note for. Um. A lot), but it's never gratuitously cruel--it's very consciously interrogating the idea of the moral story, and what sort of morality is encoded in fables, and what it means to set a story where people get what they deserve in an unjust world where that's rarely the case.

I'm nominating the unnamed editor, Champavert, his friend Jean-Louis from the introduction and the final story, and Flava from the final story; you could also nominate characters from the explicitly fictional stories.

Les Enfants du Paradis | Children of Paradise

This is a film made between 1943 and 1945 in Vichy and Occupied France and set...somewhere?...around the July Revolution, probably, I'll get into that :D. There's a DVD in print from Criterion and quite possibly available through your local library system. (And it's streaming on Amazon Prime and the Criterion Channel.)

It's beautifully filmed, with gorgeous sets and costumes and a truly unbelievable number of extras, and some fantastic pantomime scenes. (On stage and off; there's a scene where a henchman attempts to publicly humiliate a mime, and it goes about as well as you would expect.)

"Paradise," in the title, is the equivalent of "the gods" in English--the cheap seats in the topmost tier of a theater. It's set in and around the theaters of the Boulevard du Temple--the area called the Boulevard du Crime, not for the pickpockets outside the theaters but for the content of the melodramas inside them.

The story follows a woman called Garance, after the flower (red madder), a grisette turned artists' model turned sideshow girl turned actress turned courtesan, and four men who love her, some of whom she loves, all of whom ultimately fail to connect with her in the way she needs or wants or can live with.

This sounds like a setup for some slut-shaming garbage. It's not--Garance is a person, with interiority, and the story never blames her for what other people project onto her.

Of those four men, one is a fictional count and the other three are heavily fictionalized real people: the actor Frédérick Lemaître, the mime Baptiste Deburau, and the celebrity criminal Lacenaire. Everyone in this story is performing for an audience, pretty much constantly, onstage or off: reflexively, or deliberately, or compulsively.

Garance's survival skill is to reflect back to people what they want to see of themselves. She never lies, but she shows very different parts of herself to different people. We get the impression that there are aspects of herself she doesn't have much access to without someone else to show them to. Frédérick is also a mirror, in a way that makes him and Garance good as friends and terrible as lovers--an empty hall of mirrors. He's always playing a part--the libertine, the artist, the lover--and mining his actual life and emotions for the sake of his art. Baptiste channels his life into his art as well, but without any deliberation or artifice--everything goes into the character, unfiltered. It makes him a better artist than any of the others will ever be, but his lack of self-awareness is terrifying, and his transparency fascinates Garance and Frédérick, who are more themselves with him than with anyone else. Lacenaire, the playwright turned thief and murderer, seems to no self at all, except when other people are watching. Against the performers are the spectators: the gaze of others--fashion, etiquette, and reputation--personified by Count Mornay; and the internal gaze personified in Nathalie, an actress and Baptiste's eventual wife, who hopes that if they observe the forms of devotion for long enough the feeling will follow.

The time frame is deliberately vague--it's set an idealized July Monarchy where all these people were simultaneously at the most exciting part of their careers. In the real world, Frédérick turned his performance of Robert Macaire into burlesque in 1823, Baptiste's tragic pantomime Le Marrrchand d’Habits! ("The Old-Clothes Seller") played in 1842, and Lacenaire's final murder, for which he is guillotined, is 1832; these all take place in Act II of the movie within about a week of each other.

(Théophile Gautier, mentioned but tragically offstage in the film, was a fan of Baptiste; Le Marrrchand d’Habits! started as Gautier's fanfic--he wrote a fake review of a nonexistent pantomime, and the review became popular enough the Theater des Funambules decided to actually stage it. It only ran for seven performances.)

I am nominating Garance, Frédérick Lemaître, Baptiste Deburau, and Pierre François Lacenaire. You could nominate any of the other characters (Count Mornay, Nathalie, the old-clothes seller Jéricho, Baptiste's father, his landlady, Nathalie's father the Funambules manager). Gautier, regrettably, does not actually appear in the film but you can bet that's going to be one of my prompts.

So, that's one good movie you definitely have time to watch before signups, several good books you probably have time for and that are probably not like whatever else you're reading right now, and one RPF rabbit hole to go down! Please consider taking up any or all of these so that you can write me fanfic about Romantic shenanigans.

#yuletide#crosspost from Dreamwidth#petit-cenacle#champavert#children of paradise#les enfants du paradis#petrus borel

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dedication section from Rapsodies

Translators: Joseph Carter, Olchar Lindsann

The whole translation is online free here, and should really be checked out, if only for the footnotes!

Sharing this bit because Gautier references it in History of Romanticism, specifically the bit about Joseph Bouchardy :

Assuredly, the bourgeoisie will not be at all alarmed by the names dedicated that it will meet in this volume; simply, they are all young folk, like me; of heart and of courage, with whom I grew, how I love them all! It is they who make disappear for me the platitude of this life; they are all frank friends , all comrades of our camaraderie, tight camaraderie, not that of Mr. Henri Delatouche: ours he would never understand at all. Feared I not having an air of paragoning our small names to those larger, I would say that ours, ours is that of the Titien and of the Arioste, that of Molière and of Mignard. It is to you above all, companions, that I give this book! It was made among you, you may claim authorship. It is to you, Jehan Duseigneur, the sculptor, beautiful and good of heart, secure and courageous work, nevertheless ingenuous as a girl. Courage! your place would be beautiful: France for the frst time would have a French statuary.—To you, Napoléon Thom, the painter, air, frankness, soldierly handshake. Courage! you are in an atmosphere of genius. —To you, good Gérard: when then, the customs officers of literature, will they let arrive to the public committee the works, so well received from their small committees. — To you, Vigneron, who have my deep friendship, you, who prove to the coward that which can be done by perseverance; if you have carried the mortarboard, Jamerai Duval has been the drover. — To you, Joseph Bouchardy, the engraver, heart of saltpetre! — To you, Théophile Gautier. — To you, Alphonse Brot! — To you, Augustus Mac-keat! — To you, Vabre! to you, Léon! to you, O'Neddy, etc.; to you all! who I love.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

De retour de l’expo #11 : Paris romantique, 1815-1848 - Paris, Petit Palais

26 juin 2019

Il s’agit avant tout d’une déambulation dans le Paris de la Restauration et de la Monarchie de Juillet : le découpage des salles ne relève pas d’une logique chronologique, ni vraiment thématique, mais avant tout géographique, selon une progression centrifuge. La visite commence donc par le cœur de la ville, qui est aussi celui du pouvoir : le palais des Tuileries. Entre le Consulat et le Second Empire, il s’agit en effet de la résidence permanente du chef de l’Etat. Si la vie de cour y est plutôt atone, quelques figures sont populaires : c’est le cas du duc d’Orléans (le fils de Louis-Philippe) et de la duchesse de Berry, veuve du duc assassiné en 1820. Une fille de Louis-Philippe, Marie d’Orléans, se distingue par ses talents artistiques. Formée par Ary Scheffer, elle s’oriente vers la sculpture : elle est notamment l’auteure de statuettes figurant Jeanne d’Arc, dont on peut admirer trois exemples. Amatrice du Moyen Age, elle décore son appartement dans le goût néogothique, tandis que ceux de sa famille sont meublés dans un style beaucoup plus éclectique, où le goût pour le Grand Siècle côtoie le style rocaille ou néo-Boulle, sous l’influence du décorateur Eugène Lami. A noter aussi : une toile de Viollet-le-Duc représentant un somptueux dîner aux Tuileries.

Toute en longueur, la deuxième salle nous transporte au Palais Royal. Construit en 1628 pour Richelieu, il devient ensuite la résidence de la famille d’Orléans. Un premier réaménagement à la fin du XVIIIe siècle en fait un lieu vivant et prisé, avant une complète rénovation entreprise sous Louis-Philippe. La scénographie reproduit la disposition des boutiques de luxe le long de la galerie d’Orléans, édifiée alors à la place des galeries de bois. Une gravure et deux très belles maquettes d’époque restituent l’élégance de ce lieu lumineux et moderne, doté d’un verrière métallique et de l’éclairage au gaz. On y trouve les articles de luxe les plus divers, que le visiteur peut admirer dans les vitrines le long desquelles il déambule. On dispose ainsi d’un bel aperçu de la mode et du luxe de l’époque : sacs à main, très jolis éventails (dont l’un orné de girafes), incontournables châles et chapeaux, gilets, cols-cravates et cannes qui font la tenue du dandy. J’y ai appris que la canne de Balzac avait fait sensation par ses dimensions hors normes... Les arts décoratifs ne sont pas en reste : porcelaine de Paris de Jacob Petit, très colorée et un rien kitsch, couleurs claires et mates des coupes opalines, en vogue sous la Restauration (il s’agit de verres au plomb mêlés à des colorants), ou encore pendules et cartels dorés aux styles éclectiques (orientalisant, néogothique, renaissance ou rocaille). Le Palais Royal est également un haut lieu de la gastronomie parisienne, grâce aux restaurants Véry, Véfour et des Frères Provençaux, dont la carte pléthorique est exposée, comportant un grand nombre de potages, hors d’œuvres, entrées, plats de viande et de poisson, rôts, entremets, desserts, vins et liqueurs !

Cette scénographie « mimétique » se poursuit dans la troisième section, consacrée au Salon, qui se tient dans le Salon Carré du Louvre depuis 1725. Le charme de la salle (carrée, donc) tient notamment à l’accrochage des toiles, à touche-touche. Presque toutes été exposées à l’un des Salons organisés, chaque année, pendant cette période. L’ingrisme, notamment représenté par Amaury Duval, et les scènes de genre et d’intérieur côtoient toutes les nuances du romantisme : l’orientalisme, le style troubadour, le goût pour le sujet historique, notamment pour la Renaissance, François Ier et Henri IV (voir aussi Cromwell et Charles Ier (1831) de Paul Delaroche, qui connut un grand succès par ses formats monumentaux, ses sujets anecdotiques et spectaculaires – voire, ici, macabres...), le mysticisme dépouillé (et presque pré-symboliste) d’Ary Scheffer (Saint Augustin et Sainte Monique), inspiré par les peintres mystiques allemands, le sens du sublime (impressionnant Trait de dévouement du capitaine Desse du peintre de marine Théodore Gudin). Le Christ au jardin des Oliviers de Delacroix (1826) domine l’ensemble, où se distinguent aussi Mazeppa aux loups d’Horace Vernet (1826), le Roland furieux (1831) de Jehan Duseigneur, œuvre manifeste du romantisme en sculpture et, pour ma part, l’onirique Rayon de soleil (1848) de Célestin Nanteuil. Dans un sous-bois pailleté de lumière, trois nymphes se fondent dans la clarté surréelle d’un rai de soleil, suggérant ainsi le rêve du jeune écuyer endormi... Le Salon y apparaît ainsi comme un lieu ouvert aux innovations, à un nouveau langage plus libre, plus exalté, plus « sentimental » - mais finalement très divers.

L’exploration des goûts et de la production artistiques du temps se poursuit dans une salle consacrée au néogothique, et particulièrement à Notre-Dame de Paris. Une incroyable pendule reproduisant la façade de la cathédrale ouvre la salle, où figure l’édition originale du roman de Hugo (1831) à côté d’une toile de Charles de Steuben, La Esméralda (1839). On peut aussi y admirer un étonnant polyptyque d’Auguste Couder, Scènes tirées de Notre-Dame de Paris. Réalisé seulement deux ans après la parution du roman, il témoigne de son succès massif et immédiat. Ce serait un peu l’équivalent d’une adaptation cinématographique, de nos jours... Notre-Dame est aussi le personnage central des aquarelles de l’Anglais Thomas Shotter Boys, qui mêle l’intérêt pour les vieux monuments à l’observation du petit peuple de Paris. Autre lieu parisien : l’hôtel de Cluny, où Alexandre du Sommerand installe en 1832 sa collection d’objets d’art du XIIIe au XVIIe siècle, rachetée à sa mort par l’État qui y ouvre un musée en 1843. Un beau choix de papiers peints, de meubles (chaises du salon du comte et de la comtesse d’Osmond), d’horloges, de coffrets, de candélabres et de divers bibelots en bronze doré, met en lumière la vogue des motifs gothiques, entre les années 1820 et la moitié du siècle : ogives, rosaces, pinacles, clochetons et quadrilobes issus des cathédrales font irruption dans le quotidien. L’inspiration n’est pas seulement formelle : des thèmes sont également empruntés au Moyen Age. Charles VI est ainsi présent deux fois dans l’exposition : dans les bras de sa maîtresse Odette de Champdivers, chez le sculpteur Victor Huguenin (1839), et dans un bronze d’Antoine-Louis Barye, Charles VI effrayé dans la forêt du Mans, qui connaît un vif succès au Salon de 1833.

L’aspect politique est brièvement évoqué dans la cinquième section, organisée autour du plâtre du Génie de la Bastille, qui se trouve au sommet de la Colonne de Juillet, élevée pour le dixième anniversaire des Trois-Glorieuses. L’expo insiste d’ailleurs sur la volonté d’apaisement et de concorde nationale menée par Louis-Philippe qui, en outre, achève l’Arc de Triomphe et érige le tombeau de Napoléon aux Invalides. Il est vrai que cette politique du consensus et du juste milieu demeure assez peu problématisée. C’est oublier un peu vite, me semble-t-il, que les romantiques ne furent pas que des dandys amateurs de Moyen Age, de théâtre et de jolies femmes, mais aussi des acteurs engagés dans leur époque, et que le « romantisme » est aussi, au sens large, une option politique. Le parcours se clôturera d’ailleurs sur une très rapide évocation de la Révolution de 48, uniquement présentée sous l’angle de la caricature (le Gamin des Tuileries qui s’enfonce dans le trône du roi, de Daumier) et de la désillusion (les pages ironiques de L’Éducation sentimentale sur le sac des Tuileries).

Il est vrai que chaque section, ou presque, présente des « portraits-charges » : la période apparaît ainsi comme un premier âge d’or de la caricature. L’allure excentrique des « Jeunes-France » est moquée : cheveux longs, barbes, vêtements colorés (le gilet rouge porté par Théophile Gautier à la première d’Hernani). La célèbre tête de Louis-Philippe en forme de poire côtoie le dessin beaucoup plus amer de Daumier où, sortant de leur tombe, les martyrs de 1830 soupirent avec dépit : « C’était vraiment bien la peine de nous faire tuer ! », en voyant les espoirs déçus des Trois-Glorieuses. De manière plus légère, les artistes sont la cible des petits bustes satiriques de Jean-Pierre Dantan : le plus irrésistible est peut-être celui de Berlioz, à la chevelure démesurée...

Si l’aspect politique est donc abordé avec parcimonie, la question sociale est à peine effleurée dans la sixième section, consacrée au quartier latin. Un tableau de Claude-Marie Dubufe (pourtant élève de David) représente ainsi deux jeunes Savoyards ayant quitté leur région, le temps d’un hiver, afin de s’engager comme ramoneurs à Paris. Mais la jeunesse qui est à l’honneur ici est davantage estudiantine. Les jeunes étudiants, accompagnés des « grisettes », ces « jeunes filles qui ont un état, couturière, brodeuse, etc., et qui se laissent facilement courtiser par les jeunes gens » (Littré), déambulent dans le Quartier Latin et fréquentent les bals publics. Ils sont le sujet principal des chansons de Béranger, le « poète national », des Scènes de la vie de bohème d’Henri Murger, des romans très populaires de Paul de Kock, et, surtout, des dessins plaisants de Paul Gavarni. Quelques toiles et caricatures évoquent les bals et les carnavals (notamment une Scène de Carnaval, place de la Concorde (1834) d’Eugène Lami, folâtre et enjouée), ou commémorent la fièvre de la polka, danse osée qui suscita, en 1844, une véritable « polkamanie » chez les jeunes gens.

Selon cette logique centrifuge, les deux dernières salles évoquent des quartiers plus neufs et périphériques, mais qui jouent un rôle central dans la vie intellectuelle et artistique. Si la Chaussée d’Antin est le quartier de la haute banque et des « nouveaux riches », la Nouvelles-Athènes (dans le 9ème arrondissement, là où se trouvent les musées de la Vie romantique et Gustave Moreau), plus récente, attire un grand nombre d’artistes. Géricault, Scheffer (dont une toile montre l’atelier, qui est justement aujourd’hui le musée de la Vie Romantique), Vernet, Isabey ou Delaroche s’y installent. Mais cette section est davantage consacrée à la musique. Deux alcôves dotées d’enceintes diffusent notamment des œuvres de Liszt, l’un des personnages principaux de cette salle. Il est aussi bien le sujet de portraits-charges caricaturant la virtuosité du pianiste, qui faisait courir tout Paris, que du portrait en pied d’Heinrich Lehmann, qui en capte la ferveur ascétique et l’aura toute romantique... Au milieu trône un piano Pleyel semblable à celui sur lequel jouait Chopin. Ainsi se dessine la géographie d’un Paris d’émigrés, celui de Chopin et de Liszt, mais aussi de Mankiewicz, de Heine et de la princesse Belgiojoso, patriote italienne dont le salon était l’un des plus courus. La section se clôt sur l’évocation de deux figures féminines très en vue dans le Paris de la Restauration et de la Monarchie de Juillet : Marie Duplessis (la Dame aux Camélias de Dumas fils, qui meurt en 1847) et Olympe Pélissier, maîtresse d’Eugène Sue et d’Horace Vernet (dont elle était aussi la modèle) et seconde épouse de Rossini.

De la Nouvelle-Athènes on passe aux Grands Boulevards, quartier des théâtres. On y apprend que cette longue artère présentait des visages divers. De la Madeleine aux alentours de la Chaussée d’Antin, le boulevard traversait un quartier cossu et tranquille. La Chaussée d’Antin marquait le début du «Boulevard» par excellence, cœur palpitant du Paris de la mode, formé des boulevards des Italiens et Montmartre. On y trouvait de riches magasins d’orfèvrerie ou de porcelaine, les cafés, restaurants et glaciers les plus réputés (Café de Paris, Maison Dorée, Café Riche, Café Anglais, Tortoni, Café Hardy) et les grands théâtres subventionnés (l’Opéra, le Théâtre-Italien, l’Opéra-Comique, le Théâtre-Français). La présence de huit théâtres populaires, spécialisés dans les mélodrames, vaut au boulevard du Temple le surnom de «boulevard du Crime», qui disparaîtra dans les travaux d’urbanisme haussmanniens du début des années 1860.

Caricatures, portraits et objets témoignent de cet incroyable engouement pour le théâtre. Les truculents tableaux de Louis-Léopold Boilly en témoignent d’une manière piquante : voir L'Entrée du théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique à une représentation gratis (1819). plus particulièrement du succès (et, déjà, de la médiatisation) des grandes comédiennes (Mademoiselle Mars ou Marie Dorval) et des grands comédiens (Frédérick Lemaître ou Talma). Un tableau amusant figure L’acteur Bouffé représenté dans ses principaux rôles (1848) : Victor Darjou a démultiplié la silhouette de l’un des acteurs les plus populaires du temps, Hugues Bouffé, en le représentant dans une vingtaine de rôles. Le monde du spectacle recouvre aussi l’opéra (le docteur Véron dirige l’Opéra de Paris de 1831 à 1835, lançant la vogue de l’opéra à la française) et la danse. Là encore, quelque figures se détachent : les chanteuses Laure Cinti-Damoreau, Maria Malibran et Henriette Sontag, dont les portraits ornent une série de vases de la Manufacture Darte, ou Marie Taglioni, grande ballerine romantique, qui porte à la perfection la jeune technique des pointes.

L’exposition est donc surtout didactique : les œuvres exposées le sont davantage dans un but documentaire qu’esthétique. C’est parfois un écueil : ainsi, dans la salle consacrée à Notre-Dame, un petit portrait de Mérimée n’est là que pour illustrer le propos sur la naissance des Monuments Historiques. Mais soyons juste : la salle dédiée au Salon est exceptionnelle, les pièces d’arts décoratifs remarquables et j’ai découvert ces artistes qui se font, par le pinceau, le burin ou le crayon, chroniqueurs de la vie parisienne, dans de plaisantes scènes de genre ou de mordantes caricatures : Jean Pezous, Paul Gavarni, Jean-Pierre Dantan, Louis-Léopold Boilly... La remarquable, scénographie, ambitieuse et soignée (les couleurs et l’éclairage de chacune des salles évoquent le cours de la journée, du petit matin aux Tuileries à la soirée sur les Boulevards) fait agréablement passer un propos roboratif mais passionnant. Même s’il ne fait qu’effleurer les questions politiques et sociales (qui, une fois encore, relèvent des deux axes de l’exposition, l’histoire du romantisme et l’histoire urbaine), il dresse un portrait vivant et enthousiasmant, servi par un grand nombre d’œuvres variées et de qualité, du Paris de la première moitié du XIXe siècle.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sculpture by artist Jehan Duseigneur (1808-1866) “Roland Furieux” 1867 Bronze, in the special exhibition “Paris Romantique” at the Petit Palais. This work was originally exhibited at the Salon of Paris 1831. Considered a work that manifested the ideas of romanticism in sculpture. The young artist Duseignour for his first Salon, wanted to make a show of brilliance while demonstrating his mastery of the academic nude. Choosing a passage from the epic poem of L’Arioste, the sculptor presents his hero Roland at the moment of despair when he has just learned the betrayal of Angelica, his beloved. The work is presented here just in front of Delacroix’s painting “Christ in the Garden of Olives”. . . . #Paris #eugenedelacroix #parisjetaime #petitpalais #parisart #parismonamour #parislove #romantique #Iloveparis #parisfind (at Petit Palais, musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris) https://www.instagram.com/p/B1-5HiSo4cI/?igshid=u2b0z2npopwo

#paris#eugenedelacroix#parisjetaime#petitpalais#parisart#parismonamour#parislove#romantique#iloveparis#parisfind

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Paris Romantique (1815-1845): Theodore Chasseriau : Sapho prête a se précipiter du rocher de Leucate, Auguste Preault : Tuerie, Eugene Delacroix : le Christ au Jardin des Oliviers, Jehan Duseigneur : Roland furieux, Pierre-Jean David d’Angers : la jeune Grecque au tombeau de Marco Botzaris, Antoine-Louis Barye : Tigre dévorant un gavial, Bavotet Frères : Pendule Notre-Dame, Thomas Schottet Boys : l’Hotel de Sens, Felicie de Faverezu : Lampe de l’archange St - Michel, Francois-Honore Desmalter: chaise du cabinet gothique de la comtesse d’Osmond, Augustin Jeanron: les Petits Patriotes. #petitpalais #petitpalaisparis #parisromantique #parisromantique18151848 #chasseriau #sapho #leucate #preault #delacroix #lechristaujardindesoliviers #jehanduseigneur #rolandfurieux #daviddangers #marcobotzaris #botzaris #barye #bavotet #notredame #hoteldesens #archangestmichel #desmalter #comtessedosmond #jeanron #peinture #sculpture #photooftheday #instaart #parismaville #parismaville🙏 (à Petit Palais, musée des Beaux-arts de la Ville de Paris) https://www.instagram.com/p/BytQTxWi7lQ/?igshid=t4emscuu0enh

#petitpalais#petitpalaisparis#parisromantique#parisromantique18151848#chasseriau#sapho#leucate#preault#delacroix#lechristaujardindesoliviers#jehanduseigneur#rolandfurieux#daviddangers#marcobotzaris#botzaris#barye#bavotet#notredame#hoteldesens#archangestmichel#desmalter#comtessedosmond#jeanron#peinture#sculpture#photooftheday#instaart#parismaville#parismaville🙏

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m just so glad Jehan DuSeigneur got to build his cathedral!!!

(Obviously, “his” may not be the best word, but it’s what we’ve got. I don’t think anyone can own a thing like that)

;_;

#Jehan DuSeigneur#Jeunes France#architecture#cathedrals#Romanticism#French Romantics#architecture feels#goddamnit where's your two way ticket to the underworld so you can tell your people how happy you are for them?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letter from the police on the Jeunes-France, April 5, 1832

Aaah I’ve been looking to find this somewhere for ages

this is a follow-up to a rougher police note from March!

2e Division 2e Bureau 2e Service

5 avril 1832

De soi-disant républicains dont les noms suivent parmi lesquels : Wabre (pierre, jules) rue fontaine au Roi-4, Borel (Petrus) même adresse, Borel (francisque) employé à la compagnie générale des sépultures, rue St Marc feydeau - 18, Bouchardy, graveur sur métaux, Delabrunie (Gérard) élève en médecine, Duseigneur frères, l’un sculpteur et l’autre architecte, Broclet (Léon) vérificateur en bâtiment et Sully, anglais, relieur en livre et décoré de juillet font tous partie d’une société particulière ont fondé une réunion nommée le club des cochons dont le nombre s’élèvent [sic] environ à 30 qui se comporte d’environ 30 individus ([illisible] tous jeunes et on les dit déterminés et tous armés de poignards.

Ils ont adopté des sobriquets depuis une échauffourée qui est arrivée au qu’ils ont faite passage Choiseul, et sont tous signalés comme sodomistes. Le chef de la 2e Division prie son collègue chef de la police Male de faire surveiller ces individus afin de connaître découvrir le lieu où il se réunissent et de faire connaître le résultat de ces points [?]

M. le chef de la police Male [illisible et rayé, débauche et avoir les nom de tous les membres de cette société] qui ont tous été consignés dans un opuscule de l’un d’eux Petrus Borel, intitulé Rapsodies.

Le chef de la 2e Division

Attempted translation and notes under the cut!

Attempted Translation:

The names of these so-called republicans follow: Wabre, Pierre, Jules, (living at)rue fontaine au Roi-4, Borel (Petrus) of the same address, Borel (Francisque) employed by the general company of burials, rue St Marc feydeau 18, Bouchardy, engraver of metals, Delabrunie (Gérard) medical student, the Duseigneur brothers, one a sculptor and the other an architect, Broclet (Leon), building inspector, and Sully, English, bookbinder, who wears a décoré de juillet (medal from the July Revolution), are all part of a particular society that has founded a group called the Club of Pigs which numbers about 30 individuals-- young and they say determined, and all armed with daggers.

They have adopted nicknames since having a clash in the passage Choiseul, and it is reported that they are all sodomists. The head of the 2nd division asks his colleague, Head of the Municipal police, to have these people monitored, to find out where they meet, and make known the results on these points (some confusing marks here).

M. head of Municipal Police (illegible, scratched out writing, with the words debauchery and the names of the group again) , all of which are recorded in a pamphlet by one of them, Petrus Borel, entitled Rapsodies.

-Head of the 2nd Division

Notes!

“ M. le chef de la police Male” -- the M(ale) address is apparently shorthand here for “Municipale”; I’ve translated this as “head of the Municipal police” but could very easily be wrong about that, and overall don’t know what exactly that would signify..

Names! Crying Poetry Squad Represent!

Jules “Wabre” is Jules Vabre, attempting to make his name sound more ~~ exotic; the police note that he was living with Petrus Borel at this point (it’s confirmed in various memoirs that they did live together for a while).

-I’m not sure what the “general company of burials” that Francisque Borel worked for was?

- Bouchardy= Joseph Bouchardy, soon to be a well known playwright, started as an engraver

- Delabrunie = Gérard de Nerval, of course

- the Duseigneur brothers: only the sculptor, Jehan Duseigneur, would become fairly well known; you can still see some of his work in the Louvre , and in churches around France

- Leon Broclet: I suspect this is Leon Clopet, mentioned in several letters and accounts as one of Borel’s architect friends

- Sully: An English bookbinder, who apparently had a fighting role and got a medal for combat in the July Revolution! I’ve not heard about him before, and that’s a shame , because he sounds interesting!

As mentioned in the last line, all of these people (except Sully) are mentioned in the Preface to Petrus Borel’s Rapsodies, a translation of which can be seen right here!

- I know nothing about the “échauffourée” in the passage Choiseul; certainly Borel and many of his friends were a fighty bunch in general, but I’ve not read an account of this “clash” particularly. But I do know they were all going by these Very Daring Romantic Nicknames well before 1832-- most of them by 1829 at least, if not earlier (and “Petrus” wasn’t any sort of Romantic nickname, unless it was one from his family, since he was using it with them as a kid). Note that the police don’t seem to know about the de Nerval name for Gérard yet, though that was also in use.

- about the passage Choiseul, a Tripadvisor writeup says: "Passage Choiseul is one of the covered passages of Paris, and is the continuation of Rue de Choiseul. The passage was opened in 1827 and is mentioned in two novels by author Louis-Ferdinand Céline. It is the longest covered passage in the city, at 190 meters long and 3.7 meters wide and is a registered historic monument in France.”

- “it is reported they are all sodomists”-- and armed with daggers! This appears to be a fairly random spot of homophobia; the issue at hand is republicanism and general disturbances of peace. But it was, indeed, Reported!

- “M. head of Municipal Police (illegible, scratched out writing, with the words debauchery and the names of the group again) , all of which are recorded in a pamphlet by one of them” : all the names (except Sully) are, as said, mentioned in the preface to Rapsodies, along with a very blatant declaration of republicanism. But here’s the draw back to “debauchery” again. Hey head of the 2nd Division, their Politics are up here :P

The original of this letter is still on file in the Paris police archives!

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

More from Jehan Valter’s account of the premier of Le Roi s’amuse:

The romantic camp was divided into bousingots and Jeune-France.

After the July revolution, the Republicans who had adopted the Marat vest, the Robespierre hair and the boiled leather hat called Bousingot, were given the name of bousingots.

In his eccentricities of language, M. Lorédan-Larcheydit said that the word Bousingot signified “maker of bousin (noise)”. It is true, adds M. Charles Asselineau, the author of the Bibliographie romance, it is true that the Bousingots very much liked the noise; but who then did not love it at that time? No doubt, the Bousingots had fought at Hernani and broke their share of seats, but that's all. The Bosingouts alone were at the barricades of 1832. There is the difference between them and the Jeune-France.

They were the two branches of the same tree. Both belonged to the romantic trunk. Bousingots and Jeune-France enveloped in a common hatred the Academy, the classics, the clown, the bald men and the bourgeois, and professed the same cult for the Middle Ages, the color, the noise and the oddness. Only, while the Young-France, inspired by the Byronnian sadnesses, hid their health and their good humor under elegiac and morbid exteriors, while they were satisfied with the freedom of the enjambement, and that they dreamed of revolutions as those of art, the Bousingots manifested political sentiments of extreme violence at least in form.

For eight days the Bousingots and Jeune France had been boiling. The meetings followed one another in the studio of Jehan Duseigneur, the sculptor, Rue Madame, near the Luxembourg and in the studio of Achille Deveria, buried in the gardens of the Rue Notre-Dame des Champs. Friends brought friends, and counted each other.

Translator’s notes and French under the cut:

- People meeting in the studio, handing out tickets to friends who hand them out to friends, ramping up excitement in the week before the show-- the Romantic Army strategy of Hernani is still active (and would be through Hugo’s next few plays).

-It’s interesting that Valter’s accepting both the more orderly spelling of “Jeune-France” and the idea that “bouzingo” was a separate branch from the Jeunes-France but still solidly part of the Romantic movement. IME the divide wasn’t even as pronounced as that--it was the avowedly apolitical Gautier who wanted to get a Tales of the Bouzingo anthology going, after all--, but it’s certainly closer to the truth than the usual line taken by people who try to normalize the words.

- Case in point for the lack of real separation, he cites Jehan du Seigneur and Achille Deveria’s studios as the primary gathering places. Du Seigneur was still involved with Saint-Simonian and possibly even Avadamiste groups at this point, and Deveria was one of the most outspoken and activist republicans in the movement, and worked as a political artist with Philipon (the publisher who kept employing Daumier through several government lawsuits).

Le camp des romantiques se divisait en bousingots et en Jeune-France.

Après la révolution de Juillet, on donna le nom de bousingots aux républicains qui avaient adopté le gilet à la Marat, les cheveux à la Robespierre et le chapeau en cuir bouilli des marins appelé Bousingot.

Dans ses excentrités du langage, M. Lorédan- Larcheydit que le mot Bousingot signifiait faiseur de bousin. Il est vrai, ajoute M. Charles Asselineau, l'auteur de la Bibliographie romantique, il est vrai que les Bousingots aimaient fort le tapage; mais qui donc ne l'aimait pas à cette époque? Sans doute, les Bousingots avaient combattu à Hernani et cassé leur part de banquettes, mais voilà tout. Les Bosingouts seuls étaient aux barricades de 1832. Là est la différence entre eux et les Jeune -France. C'étaient les deux branches d'un même arbre. L'une et l'autre appartenaient au tronc romantique. Bousingots et Jeune-France enveloppaient dans une haine commune l'Académie, les classiques, le poncif, les hommes chauves et les bourgeois, et professaient le même culte pour le moyen âge, la couleur, le bruit et la bizarrerie. Seulement, tandis que les Jeune-France, s'inspirant des tristesses byronniennes, cachaient leur santé et leur belle humeur sous des dehors élégiaques et maladifs, tandis qu'ils se contentaient des libertés de l'enjambement, et qu'ils ne rêvaient de révolutions que celles de l'art, les Bousingots manifestaient des sentiments politique d'une extrême violence du moins dans la forme.

Depuis huit jours, les Bousingots et les Jeune- France étaient en ébullition. Les réunions se succédaient dans l'atelier de Jehan Duseigneur, le sculpteur, rue Madame, tout près du Luxembourg et dans l'atelier d'Achille Deveria, enfoui au milieu des jardins de la rue Notre-Dame des Champs. Les amis amenaient des amis, on se comptait.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

La première de Le roi s'amuse: the gang’s all here

More from Jehan Valter’s La première de Le roi s'amuse:

The general rendezvous was between four and four-thirty in the black gallery of the artists' entrance. Theophile Gautier and Celestin Nanteuil each brought fifty friends or partisans; Achille Deveria and Jehan Duseigneur brought about as much; Petrus Borel, the lycanthrope, arrived the last, followed by a long column of students in berets and rapins (art students) with pointed beards, singing at the top of their heads:

Poulot goes off to war,

Mironton, your tone, mirontaine;

Poulot goes off to war,

Don’t know when he’ll come back.

A chorus set in fashion by the Republicans, and designating the Duke of Orleans, who had just left for the siege of Antwerp.

Notes and original French under the cut:

- “singing at the top of their heads”-- I don’t know if the closer colloquialism in English would be “singing at the top of their lungs”(loudly) or “singing off the top of their heads (that is, impromptu, or improvising)” so I left it at the more direct translation; also, I really love the phrase “off the top of their heads”. But clarification would be appreciated!

-I don’t know much about the Duke and the Siege of Antwerp, sorry! I’d just be copying ol’ Wiki here.

-I am forever amused by how everyone who writes about them specifies “Petrus Borel, the lycanthrope” like Cecil talking about John Peters, You Know, The Farmer, as if there was a herd of other Petruses Borel running around and they needed to make this clear, oh and also we gotta let everyone know he’s a frigging werewolf.

Le rendezvous général était entre quatre heures et quatre heures et demie, dans la galerie noire de l'entrée des artistes. Théophile Gautier et Célestin Nanteuil amenèrent chacun une cinquantained'amis ou de partisans; Achille Deveria et Jehan Duseigneur en amenèrent à peu près autant; Petrus Borel,le lycanthrope, arriva le dernier, suivi d'une longue colonne d'étudiants en bérets et de rapins à barbes pointues, chantant à tue-téte :

Poulot s'en va t'en guerre,

Mironton, ton ton, mirontaine;

Poulot s'en va t'en guerre,

Ne sait quand reviendra.

Refrain mis à la mode par les républicains, et désignant le duc d'Orléans, qui venait de partir pour le siège d'Anvers.

#Four People and a Shoelace#Le Roi s'amuse#Petrus Borel#Jehan Valter#Jehan du Seigneur#Theophile Gautier#Celestin Nanteuil#Achille Deveria

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

La première de Le roi s'amuse,cont

more from Jehan Valter; this is further along , and the play and its reception are starting to go off the rails:

Unfortunately, the spectators of the parterre and the amphitheater recommenced their jokes during the intermission; appealing to the tenants of the lodges and the balcony, already ill-disposed to the author (Hugo).

Messrs. Arnault pere and his sons, Jouy, Jay, and Viennet, who had signed a passionate protest against the Romantics some time before, were particularly beset. We* sang on the air of Malborough:**

The academy is dead,

Mironton tone your mirontaine,

The academy is dead,

Is dead and buried.

By the time the curtain was about to rise on the second act, a shower of small papers thrown from the third gallery fell unexpectedly onto the audience of the orchestra and the lower galleries. It was Jean Journet "the apostle" who thus announced to the world by printed flyers that a new religion had just been founded and that he was the founder.

Reading these little papers put the whole room in a good mood. We laughed again when the second act began. But the laughter stopped abruptly from the first few verses of the monologue of Triboulet.

This old man cursed me ...

And they changed into enthusiastic bravos from the scene where the unfortunate father said to his daughter:

Oh ! do not wake up a bitter thought.

The verse :

And what would you say if you saw me laughing?

shuddered the whole room. Friends and enemies of the author met in a single ovation. The end of the act went less well. People say- but nothing proves it and I like to doubt it- Samson (Clement Marot), dissatisfied with playing only one end of a role***, deliberately misplaced the band over Triboulet's eyes, and also deliberately forgot the following two explanatory verses:

You can scream high and walk with a heavy step.

The blindfold that makes him blind and deaf.

So that it was not explained how Triboulet did not see that the ladder was applied against the wall of his house and how he did not hear the cries of his daughter. The audience of the lodges burst out laughing.

In addition, Blanche's abduction was as awkward as possible. Mademoiselle Anais was swept upside down with her legs in the air, and the second act ended amid laughter and whistling.

During the passage, Jehan Duseigneur**** ascended to the third gallery, where he had a lively explanation with Journet. Going down, he had to cross the home a group of Lesguillon, Charles Maurice Henri Beyle and a few others, all opponents of the author. The group was heavily eroding the room, that goes without saying.

"Down with the fools!" said the Romantic sculptor energetically.

Nobody answered him and he regained his place proudly.

* This isn’t the first time Valter’s talked about the Romantics as “we” and given his name , it’s likely he really was part of the crew. If so , this pamphlet on Le Roi s’amuse,started as a running article in Le Figaro, is the only writing of his that seems to have survived--though of course it’s possible he has other columns buried in old newspaper articles and the like.At any rate, this is the whole evidence of him that I’ve found, so sadly I can’t give more info on him! But there’s another Jehan for the Romantic Army ; maybe he was a footsoldier and not a lieutenant, but obviously the sense of camraderie stuck with him too.

**Obviously, filking the same song Petrus and his group were singing at the start of the play

*** I am really not sure what this means??

****Duseigneur!! Besides being one of the main hosts of the Jeunes-France, he was the guy who did his hair up like a flame to symbolize THE FLAME OF GENIUS. A noticeable guy, a big success in his art, and well liked, but mostly without speaking lines in histories of the movement--this is fun to see!

Malheureusement, les spectateurs du parterre et de l'amphithéâtre recommencèrent leurs plaisanteries pendant l'entr'acte; interpellant les locataires des loges et du balcon, déjà mal disposés pour l'auteur.

MM. Arnaultpère et fils, Jouy, Jay et Viennet, qui avaient signé quelque temps auparavant une protestation passionnée contreles romantiques, étaient particulièrement pris à partie. On chantait sur l'air de Malborough :

L'académie est morte,

Mironton ton ton mirontaine,

L'académie est morte,

Est morte et enterrée.

Au moment où le rideau allait se lever sur le second acte, une pluie de petits papiers lancés de la troisième galerie tomba à l'improviste sur le public de l'orchestre et des galeries inférieures. C'était Jean Journet « l'apôtre » qui annonçait ainsi au monde par prospectus imprimés qu'une religion nouvelle venait de se fonder et qu'il en était, lui, le fondateur.

La lecture de ces petits papiers mit la salle entière en belle humeur. On riait encore lorsque commença le deuxième acte. Mais les rires cessèrent brusquement dès les premiers vers du monologue de Triboulet.

Ce vieillard m'a maudit...

Et ils se changèrent en bravos enthousiastes à partir de la scène où le malheureux père dit à sa fille :

Oh ! ne réveille pas une pensée amère.

Le vers :

Et que dirais-tu donc si tu me voyais rire ?

fit frissonner toute la salle. Amis et ennemis de l'auteur se réunirent dans une même ovation. La fin de l'acte marcha moins bien. On prétend— mais rien ne le prouve et j'aime mieux en douter— que Samson (Clément Marot), mécontent de ne jouer qu'un bout de rôle, fit exprès de mal placer le bandeau sur les yeux de Triboulet, et fit également exprès d'oublier les deux vers explicatifs qui suivent :

Vous pouvez crier haut et marcher d'un pas lourd.

Le bandeau que voilà le rend aveugle et sourd.

De sorte qu'on ne s'expliqua pas comment Triboulet ne voyait pas que Péchelle était appliquée contre le mur de sa maison et comment il n'entendait pas les cris de sa fille. Le public des loges éclata de rire.

En outre, l'enlèvement de Blanche se fit aussi maladroitement que possible. M" e Anaïs fut emportée la tête en bas et les jambes en l'air. Le deuxième acte finit au milieu des rires et des sifflets.

Pendant Tentr'acte, Jehan Duseigneur monta à la troisième galerie où il eut une vive explication avec Journet. En redescendant, il dut traverser au foyer un groupe composé de Lesguillon, de Charles Maurice, de Henri Beyle et de quelques autres, tous adversaires de l'auteur. Le groupe éreintait fortement la pièce, cela va sans dire.

— A bas les stupide! si cria énergiquement le sculpteur romantique.

Personne ne lui répondit et il regagna fièrement sa place.

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

It is to you above all, companions, that I give this book! It was made

among you, you may claim authorship. It is to you, Jehan Duseigneur, the sculptor, beautiful and good of heart, secure and courageous work, nevertheless ingenuous as a girl. Courage! your place would be beautiful: France for the frst time would have a French statuary.—To you, Napoléon Thom, the painter, air, frankness, soldierly handshake. Courage! you are in an atmosphere of genius. —To you, good Gérard: when then, the customs officers of literature, will they let arrive to the public committee the works, so well received from their small committees. To you, Vigneron, who have my deep friendship, you, who prove to the coward that which can be done by perseverance; if you have carried the mortarboard, Jamerai Duval has been the drover. — To you, Joseph Bouchardy, the engraver, heart of saltpetre! — To you, Théophile Gautier. — To you, Alphonse Brot! — To you, Augustus Mac-keat! — To you, Vabre! to you, Léon! to you, O'Neddy, etc.; to you all! who I love.

from the Preface to Rhapsodies by Petrus Borel (1832), translated by Olchar Lindsann

(Because 3 AM in the morning is a good enough time as any, to have emotions about French Romantics and how adorable their friendship was.)

27 notes

·

View notes