#J. Edgar Hoover

Text

J. Edgar

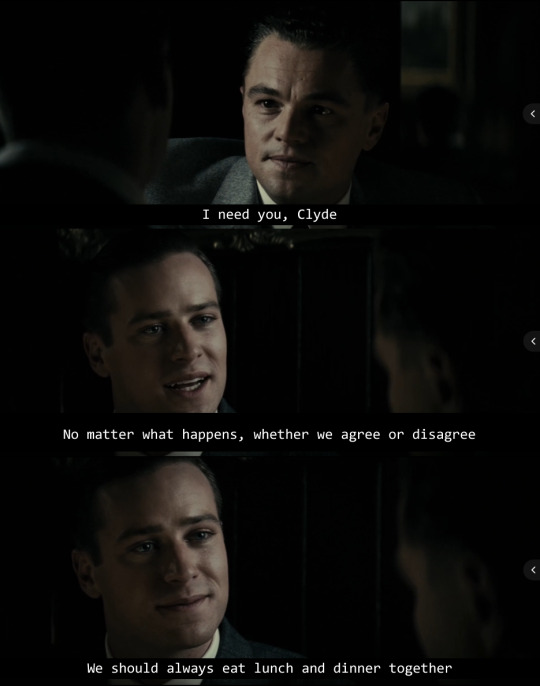

I'm more than devastated. It is incredible. I cried for more than 30min.

You'll learn why Hoover was controversial but at the same time you'll understand and accept how he was. The old-age makeup can be cringy and it does take some time to get used to but the relationship between Hoover and Tolson is just deep felt. I didn't quite enjoy the slow pace and music but in the end they really made sense to me.

How can anyone love another person like Tolson did!?!? The best part, he's portrayed by Armie🙏

\\Armie looks immaculate in vintage fashion//

My fav Armie film aside from U.N.C.L.E.(and CMBYN!)😭🙏

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

J. Edgar Hoover portant un masque de Mickey Mouse lors d'une soirée du Nouvel An.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Those who shout about "law and order" are frequently law breakers themselves; Criminals with political power.

17 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Crime books, comics and other stories packed with criminal activity and presented in such a way as to glorify crime and the criminal may be dangerous, particularly in the hands of an unstable child. A comic book which is replete with the lurid and macabre; which places the criminal in a unique position by making him a hero; which makes lawlessness attractive; which ridicules decency and honesty; which leaves the impression that graft and corruption are necessary evils of American life; which depicts the life of the criminal as exciting and glamorous may influence the susceptible boy or girl who already possesses anti-social tendencies.

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, at the Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency in 1950, being entirely unoriginal and of course entirely wrong

cited in Bart Beaty, Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture (University Press of Mississippi, 2005)

#J. Edgar Hoover#comics#rogues in fiction#train them young#analysis#information wants to be free#Bart Beaty#Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Black Panther Party suffered very directly from J. Edgar Hoover:

It was in the end a group that adopted both the organization and the phrasing and a great deal of the goals of a standard Soviet-style communist party of the Cold War. In a Cold War context this was all it would have taken to draw the malice of even the most kindly people, of whom J. Edgar Hoover was not. It did not matter that the Black Panthers used the rhetoric that in other societies led to slave labor camps and mass executions to build the infrastructure for free lunches, to Hoover they were the perfect excuse for the kind of abuses he indulged in and to expanding Cointelpro, as well as the most classic examples of the specific places and people targeted by it.

As far as Vanguardist parties go, the Black Panther Party was the kindliest they got. Didn't save them, and it didn't prevent Hoover exploiting divisions and Newton embracing the Stalinist purge logic from causing the movement's collapse.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#the long civil rights movement#black panther party#cointelpro#j. edgar hoover

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

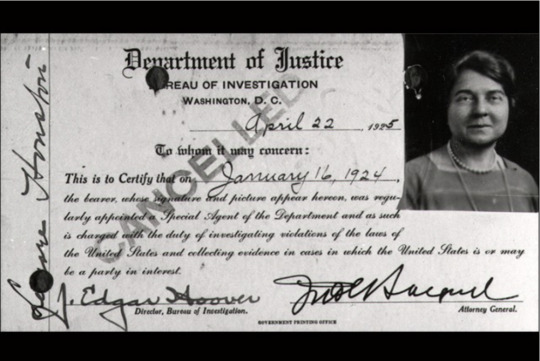

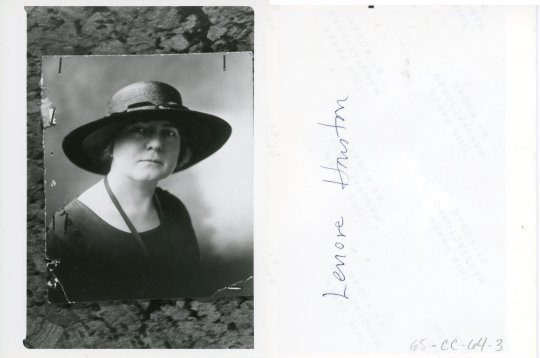

[Image description:A black and white photo of Special Agent Lenore Houston. She wears her hair pulled back, pearls, and a dark coat. ]

This is Special Agent Lenore Houston, one of only three female Bureau of Investigation agents hired before 1972. Her history is shrouded in mystery and in the process of writing "The Case of the Penumbral Gate" (our next season which we’re crowdfunding for right now and ends 11/23/22). We hope to uncover more of her real history and imbue our fictional character, Special Agent Lake, with authentic experiences pulled from Houston's life.

As Sarah Rhea Werner, who plays her on the show pointed out, in the above photo Special Agent Houston "just looks f---in' PISSED."

When J. Edgar Hoover came to power, he asked for the resignation of the two existing female agents, Davidson and Duckstein. Houston has the strange distinction of being the only female agent hired during Hoover's nearly 50 years of tyranny as Director of the FBI.

[ Image description: Special Agent Lenore Houston's form and photo certifying her as an agent. a CANCELLED stamp is across it. ]

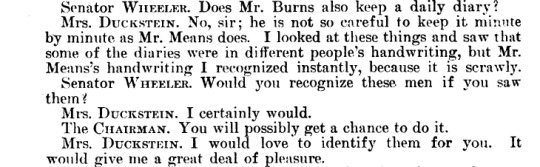

Side note: Duckstein, who we can't find any photos of, has her own wild story and Hoover targeted her for testifying against the Bureau's illegal investigative techniques. We're looking into her too. Below is an excerpt from page 547 of the Investigation of the Former Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty, in which Duckstein is intensely charming in her enthusiasm to point out some creepy perps in this scandal.

[Image description: An excerpt from page 547 of the Investigation of the Former Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty, transcripts of Duckstein where she says it would give her great pleasure to identify some shady characters. ]

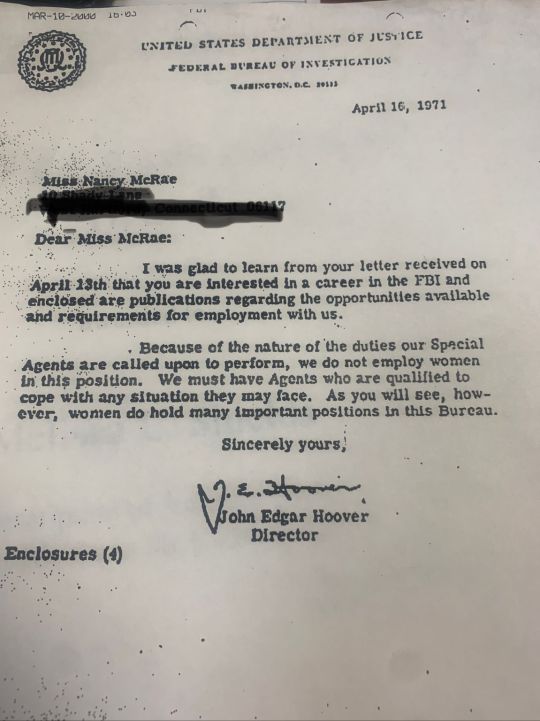

Hoover, famously misogynistic (see below letter from 1971), was against Houston becoming an agent, but after pressure from the Pennsylvania Governor & a Congressman on her behalf, he conceded & she was an active agent from 1924 to 1928. Who was she and how did she have such powerful allies? No one knows.

[Image description: A famous letter from Director Hoover in 1971 in which he insists that women are unfit to be FBI agents. ]

Houston was born in a town that no longer exists (Collamer, PA), went to Swarthmore College, belonged to Pi Beta Phi - the first female secret society in the US, and was unmarried. Between graduating college and becoming a Special Agent at 45 there's 20 years unaccounted for.

[Image description: An image from @usnatarchives of Lenore Huston in a studio photograph from the bust up, wearing a wide-brimmed hat. ]

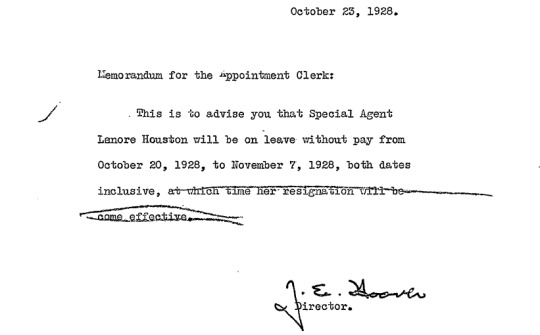

In her last year as an agent, Hoover personally wrote several memos retroactively placing her on leave (very unusual) until asking her resignation. Two years later she was institutionalized, reportedly hallucinating and threatening to shoot Hoover if she was ever released.

[Image description: Hoover's final letter retroactively placing Houston on leave without pay and asking her resignation.]

Houston died in 1933, and her strange final years suggest a sinister story. She moved from the Philadelphia office to the Washington D.C. office in 1927 and an outstanding career turns sour, the more Hoover directly gets involved. During a time where it was very easy to call a woman hysterical and have her institutionalized (especially a gender-nonconforming unmarried woman of almost 50) it's easy to read that Hoover silenced her. It's in his playbook.

[Image description: An illustration by Jarrod Pope of Special Agent Lenora Lake from The Call of Cthulhu Mystery Program, rendered in the style of a sepia toned photograph. Lake looks disheveled, wearing a dress and hat, holding a gun.]

Agent Lake's story is going to be very different from Houston's - very much her own, but very informed by Houston's life, times, work environment, and perhaps even the history of her fellow female agents. Though all of this informed the character that Sarah played in our initial roleplaying session, this history isn't at the center of "The Case of the Penumbral Gate". We're hoping that we'll be able to meet our stretch goal to do a standalone Agent Lake special so we can dive deep into all of this and tell the story of how untangling a conspiracy in Washington D.C. puts Agent Lake in Director Hoover’s crosshairs. There’s something weird going on and no one is listening. Naturally, this world-weary non-conformist has to take matters into her own hands.

If you want to hear this story and help us do research that as far as we know no one else has done into the lives of these Agents, please spread the word far and wide. Let's see if we can get this campaign funded and reach these stretch goals!

#special agent lenore houston#lenore houston#sarah rhea werner#historical fiction#audio drama#crowdfunding#bureau of investigation#fb#federal bureau of investigation#j. edgar hoover#women of history#the mann act#lovecraft#hp lovecraft#call of cthulhu#deviant women#fbi agent#actual play#rpg audio drama#the call of cthulhu mystery program

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

On January 17, 2020 It's Alive and The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover were screened as a double-feature on TCM Underground.

#tcm underground#it's alive#the private files of j. edgar hoover#larry cohen#exploitation films#grindhouse movie#cult movies#biopic#horror art#j. edgar hoover#horror movies#monster movies#political thriller#political films#horror film#horror#monsters#movie art#art#drawing#movie history#pop art#modern art#pop surrealism#portrait#cult film

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

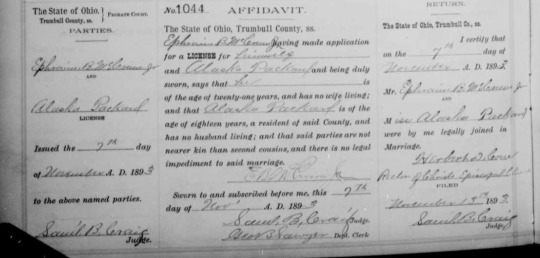

"Sister of the Packard men": The unusual story of Alaska Packard Davidson

Portrait picture of Alaska, presumably in 1922, via Wikimedia, which posted this public domain image

Recently, in going through some documents made searchable and digitized by the Library of Congress, I came across one Alaska Packard Davidson, who is described on her Wikipedia page as "an American law enforcement officer who is best known for being the first female special agent in the FBI." At age 54, she joined the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) in October 11, 1922 as a special investigator, with a starting salary of $7 a day, which went up to $11 a day when traveling, first working at the New York office (where she went for training), then at the Washington office. [1]

Although the BOI, the FBI's precursor, wanted to hire women for cases related to combating intersex sex trafficking, she was considered "refined" so she wasn't put on such cases, meaning the BOI considered her of "limited use" in prosecuting such crimes, partially due to her limited schooling. [2] Instead, she was involved in a case against an agent who sold classified DOJ information to criminals, for example. [3] After the resignation of her former boss, William J. Burns, who was caught up in the Teapot Dome Scandal, she was forced out by J. Edgar Hoover, who had become the Bureau's acting director in 1924. He asked her to resign after the special agent leading the Washington field office, E.R. Bohner, said he had "no particular work for a woman agent."

She resigned on June 10 of the same year, even though there was no indication her work was unsatisificatory. Before that point, she still was able to transmit information to the BOI on the Fourth International Congress of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), a women's peace activist group, in May 1924, under the name of A.P. Davidson, informing the agency, including Hoover, about their activities, because they claimed that Jane Addams was committing "treason" (a lie). [4] Following her, and with the resignation of other agents in the 1920s (Jessie B. Duckstein and Lenore Houston), the BOI, then FBI, had no female agents for 43 years, between 1929 and 1972! There is more to her life than her brief stint in the BOI, crossing some ethical boundaries by spying on WILPF by telling the BOI about its activities. Despite this, the agency still celebrates (also see here) her, despite the problematic history, as I just described, and role of Hoover in her ouster from the BOI.

Here's what we do know. Alaska "Al", likely named after the then-territory of the same name, was born in Ohio, on March 1, 1868, to Warren Packard and Mary Elizabeth, with her two brothers, James Ward and William Doud, who both founded the Packard auto company. She was first listed in the 1870 census as a 2-year-old girl, with James and William in the house, as was her 1-year-old sister Carlotta, and the household headed by Warren, a hardware merchant, and his wife, Mary. [5] In 1880, she was living with her parents, siblings (William, James, and Carlotta) in Chautauqua, New York. She had another sister, named Cornelia Olive, as well.

Via "Ohio Marriages, 1800-1958", database, FamilySearch, 25 March 2020, Alaska Packard in entry for Ephraim B. McCrum, 1893, Marriage Record Vol. 10: 1890-1895, Trumbell County, Ohio page 348, image number 214 of 638. This was also confirmed by a 1897 newspaper clipping which called her "Mrs. E. B. McCrum."

Al had been in public school for three years and did not have a college, or university education. Cindee Mines notes on the Trumbell County Historical Society (TCHS) website that she grew up as the daughter of a wealthy territory, living in a huge mansion "on High Street at Mahoning Avenue in the mid 1870’s," and that while there is no evidence she had any higher education, she was a "well-known equestrian, winning awards at county fairs in her teenage years," even put in charge of the "New York and Ohio plant" for Packard Electric in 1890. Beyond that, she married two times. In 1893, she married a man named Ephraim Banks McCrum Jr., a close friend of her father, in Trumbell County, Ohio, as shown above. She had a daughter named Esther in 1894. [6] In 1900, the federal census showed her as married and with one child, while also confirming she had been married for seven years. [7] By then, however, she had, according to the aforementioned TCHS biography, had divorced Ephraim, with Esther living in a Columbus hospital known as the “Institution for Feeble-Minded Youth”. The same census showed her living with her widowed mother, Mary, brothers W.D. and William, and sisters, Carlotta and Cornelia. Esther sadly died in 1902 at the age of 8, of pneumonia, although TCHS said it was tuberculosis. [8]

At some point before 1910, she married a man named James B. Davidson, who was well-known to the Packard family. She is shown in the 1910 census as his wife, living in O'Hara Township, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, with two boarders: a 32-year-old man named Fred Osterley and an 18-year-old woman named Jessie Osterley. [9] A land record the previous year noted Al and James Ward Packard owning a tract of land named Lakewood in Chautauqua, New York. [10] The THCS biography says she purchased over 100 acres in Accotink, Virginia, which is near Mount Vernon, an unincorporated area in Fairfax County, living there with horses and a dog.

By 1920, she was living in Mount Vernon, Fairfax, Virginia, with James and a 16-year-old servant, from Maryland, named James Cot. [11] In 1925 she joined a petition to the New York Supreme Court for an appraisal transfer tax. Then came the letters between herself and Carrie Chapman Catt in 1927. On May 26, Carrie told her about a story from Harriet Taylor Upton, assuming it was a man who came to her with a list of suffragettes compiled by the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), thanks to information from Ms. Mary Kilberth (a leading anti-suffragist) and Robert Eichelberger, the husband of famed suffragist Bessie R. Lucas Eichelberger. She says the list is from the Secret Service, but I think she means the BOI. She then said that she was writing an open letter to the D.A.R., because the first individual was part of it, saying that this material is fodder to anti-suffragists. She then added:

In view of the fact that you no longer are connected with the Department [The Bureau of Investigation], I think you might allow me to make this statement. In the event the government should make inquiry, which it is not likely to do, as to who this person was and I was driven in a corner, I might have to give your name. I do not think you would need to apologize and I believe that your name would not be asked for. I would certainly not give it unless I was driven to it and, indeed, I would agree not to give it until I had again consulted you, letting you know what the condition is under which the pressure has been made.

On May 30, Al responded, saying that she would be fine to use her name, forgetting most of the women on "Miss Kilbreth's list" and said that Kilberth accused Catt "of something…in connection with your South American trip and she couldn't say enough against Mrs. Upton." The final letter in this file is Carrie's reply on June 25. She first apologizes for not acknowledging the letter more promptly, and said two people will be sent to her, stated her intention to write about this incident, and concluded by saying "it is a pity that the anti-suffragists are such poor sports that they cannot overcome their disapproval of us." What I take from this whole exchange is that Al was a suffragist, which really isn't much of a surprise, and that the BOI had compiled a list of suffragists, for who knows what end.

But that's not the whole story. In a May 27, 1927 letter from Harriet Taylor Upton to Carrie, Harriet says the D.A.R. is lifting up an anti-suffragist member, and even noted that she pushed for more women to be appointed within the government, including Al. She proceeded to give a brief description of Al, which gives details about her life:

When I went to Washington in the Republican [Party] Headquarters, I tried not to get places for anybody in government. I did a great deal towards the appointment of women to key positions, but not regular government positions. I made one exception and that was the daughter of a citizen of Warren whom I had known for years. She is the sister of the Packard men who made the Packard machine. She had married rather unfortunately and was living in a little town down in Virginia. She had experience in office work, is splendid at managing people and I asked Harry Daughterty, the Attorney General, if he could find a place for her. She expected just a small place of a thousand dollars or so, and would drive back and forth from her plantation, which is a part of the Washington estate. We were surprised to have him appoint her to the Secret Service Commission [BOI?] and she worked under [William J.] Burns, the great secret service man. She got $2300.00 a year salary and she did a corking [splendid] job. It was just the kind of a job she could do. They finally took in another woman who proved to be a discredit to women and to the department and everything else.

Now in the beginning when Mrs. Davidson began her work in this department, she would come to me asking about the loyalty of this person and that person and in the course of the time she was there, I learned that Miss Kilbreth of the Patriot was stuffing the Attorney General's office with all of the lies possible. Now one day Mrs. Davidson came in with a list of names and among them were our people. I have forgotten now just who was on the list, but it was our own folks and they were just about as much traitors to the government as we are now. I therefore told Mrs. Davidson that that whole thing was just made up, and she said she had about concluded that this was true for she has always been devoted to me, and Miss Kilbreth told her awful things about me. She thought if things were no truer about other people than they were about me, there was nothing to it. I had forgotten that I ever reported this to you. I had forgotten that she threw the list in the waste basket. Of course I did not write that it was a woman who gave me the information, because I did not want anyone to know then that the secret service through personal friendship were consulting me. And you must have taken it that it was a man because all people employed were men...I do not know whether Mrs. Davidson would have any objection to your using her name or saying that it was a woman from the Attorney General's office or not. If you want me to I can write to her, or if you want to you can write direct to her, telling her what you want it for. She is out of the thing entirely now and never will get back because Mr. Daugherty is no longer there and because I am no longer there. Her address is Mrs. James Davidson, Acotink, Va.

Harriet hen goes onto say that she might sever her membership with the D.A.R. I would like to know if the D.A.R. was filled with suffragists at the time, or if Harriet was boasting. After all, Susan B. Anthony, Emily Parmely Collins, Carrie Chase Davis, and Alice Paul were recorded as members of the D.A.R. Al showed good judgment by throwing away the list of suffragists in the waste basket. Someone needs to make a film or animation of this. It would be great! There are other Packards mentioned in the papers, like a "Mrs. Packard" in Springfield, Massachusetts who is the vice-chairman for a "Mrs. Ben Hooper." [14] Also, considering that Carrie was, at the time, in a relationship with Mary "Molly" Garrett Hay, after her second husband, George Catt died in 1905, is it possible she was attracted to Al, even from their short exchange? More pertinent, it says something about the close friendship that Al and Harriet had for Harriet to comment that Al "married rather unfortunately" and say that Al "has always been devoted" to her. Maybe the friendship went further than that? In any case, Al was still married to James at the time. Even so, it appears that Harriet recommended Al for the job, at least if this letter is to be believed.

Al Packard as a teen, via the Classic Cars Journal

Three years later, in 1930, Al was widowed and still living in Mount Vernon, at a house worth about $4,000. [15] And yes, she lived alone, had a radio and no occupation listed, which is not a shock for someone 62 years old. Although she was alone, we don't know whether she had close friends or family members which kept her company, although it is possible. She was described as widowed because James had died in May 1929. It is not known whether she and Carrie, or she and Harriet ever met each other after the death of James in 1929. Keep in mind that the marriage Harriet had with a man George W. Upton, who she had been with since 1884, ended in 1923. According to the TCHS biography, she continued living on the farm until her death.

She died four years later, on July 16, 1934, in Alexandria, Virginia, at the age of 66 of various causes. [16] She lived on in many realms. She was mentioned in the episode "Waxing Gibbous" of the eighth season of Archer, a mature animation, which was described by The A.V. Club as an obscure reference, and praised by Vulture. In chapter two of Gloria H. Giroux's Crucifixion Thorn: Volume Two of the Arizona Trilogy, a character is inspired by Al, while others chattered on Twitter about renaming the FBI building after her. As some of her ancestors put it, she lived an "unusual life." She definitely did, without a doubt! There are many avenues and chances to branch out with this article, for someone who is my sixth cousin three times removed, to other topics and I hope you all enjoyed this post.

Notes

[1] Theoharis, Athan G. (1999). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 321–322. ISBN 9780897749916; Mullenbach, Cheryl (2016). Women in Blue: 16 Brave Officers, Forensics Experts, Police Chiefs, and More. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613734254; Vines, Lynn. "The First Female Agents," The Investigator, p 77-78

[2] Delgado, Miguel A. (February 4, 2017). "Alaska Packard, la primera agente del FBI despedida por ser mujer". El Español (in Spanish). Retrieved January 16, 2021; Theoharis, Athan G. (1999). The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 321–322. ISBN 9780897749916.

[3] Mullenbach, Cheryl (2016). Women in Blue: 16 Brave Officers, Forensics Experts, Police Chiefs, and More. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613734254. Her testimony before a House select committee in that case in May 1924 is shown on pages 2492 to 2495 of [Investigation of Hon. Henry Daughtery Formerly Attorney General of the United States] Hearings Before the Select Committee on the Investigation of the Attorney General, United States Congress, Senate Sixty-Eighth Congress First Session Persuant to S. Res 157 Directing a Committee to Investigate the Failure of the Attorney General to Prosecute or Defend Certain Criminal and Civil Actions Wherein the Government is Interested: May 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, and 22, 1924 [Part 9] (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1924).

[4] Davidson, A.P. "Re - Women's International League of Peace and Freedom: Report of Fourth International Congress," File 237, May 7, 1924, within "Jane Addams Part 1 of 4," FBI, The Vault, Pages 2-9; Davidson, A.P. "Re - Women's International League of Peace and Freedom: Report of Fourth International Congress," File 4237, May 5, 1924, within "Jane Addams Part 3 of 4," FBI, The Vault, Pages 18-25; Davidson, A.P. "Re - Women's International League of Peace and Freedom: Report of Fourth International Congress," May 5, 1924, within "Jane Addams Part 3 of 4," FBI, The Vault, Pages 26-39; Davidson, A.P. "Re - Women's International League of Peace and Freedom: Report of Fourth International Congress," May 5, 1924, within "Jane Addams Part 3 of 4," FBI, The Vault, Pages 40-46, continued in "Jane Addams Part 4 of 4," FBI, The Vault, pages 1-6. Parts of her report may also be on pages 1-29 of "Jane Addams Part 2 of 4." Her reports didn't matter, as Meredith Dovan wrote, on page 18 of her thesis, "FBI Investigations into the Civil Rights Movement and the New Left" that "Hoover fired both women [Alaska and Jessie B. Duckstein] during a round of cuts after he became acting director of the FBI in May 1924."

[5] “United States Census, 1870,” database with images, FamilySearch, James W Packard in household of Warren Packard, Ohio, United States; citing p. 21, family 5, NARA microfilm publication M593 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 552,771; "United States Census, 1880," database with images, FamilySearch, 13 November 2020, Alaska Packard in household of Warren Packard, Chautauqua, New York, United States; citing enumeration district ED 39, sheet 30B, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), FHL microfilm 1,254,815.

[6] "Ohio, County Births, 1841-2003", database with images, FamilySearch, 1 January 2021), Alacha Packard in entry for Esther McCrum, Birth registers 1883-1896 vol 3., page 184, image 183 of 289.

[7] “United States Census, 1900,” database with images, FamilySearch, William Packard in household of Mary Packard, Warren Township Warren city Ward 1, Trumbull, Ohio, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) 120, sheet 13A, family 297, NARA microfilm publication T623 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1972.); FHL microfilm 1,241,325.

[8] "Ohio, County Death Records, 1840-2001," database with images, FamilySearch, 14 December 2020, Alaska P. Mc Crum in entry for Esther Mc Crum, 20 Apr 1902; citing Death, Columbus, Franklin, Ohio, United States, source ID v 3 p 240, County courthouses, Ohio; FHL microfilm 2,026,910.

[9] "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch, accessed 16 January 2021, Alaska Davidson in household of James B Davidson, O'Hara Township, Allegheny, Pennsylvania, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 185, sheet 10A, family 212, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 1296; FHL microfilm 1,375,309.

[10] "United States, New York Land Records, 1630-1975", database with images, FamilySearch, 27 December 2020, Alaska P Davidson in entry for James Ward Packard, 1910, Grantees 1902-1910 vol A-Z, image 564 of 811, page 592. The liber is noted as 388 and the page as 477, but this volume appears to not be digitized as of yet.

[11] "United States Census, 1920", database with images, FamilySearch, accessed 4 January 2021, Alaska Davidson in household of J B Davidson, Mount Vernon, Fairfax, Virginia, United States, citing enumeration district (ED) ED 36, sheet 7B, family 130, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 1886; FHL microfilm 1,821,886.

[12] Catt, Carrie Chapman. Carrie Chapman Catt Papers: General Correspondence, Circa 1890 to 1947; Davidson, Alaska P. - 1947, 1890. Manuscript/Mixed Material, pages 1-3, Letters on May 26, 1927, May 30, 1927, and June 25, 1927.

[13] Catt, Carrie Chapman. Carrie Chapman Catt Papers: General Correspondence, Circa 1890 to 1947; Upton, Harriet Taylor. - 1947, 1890. Manuscript/Mixed Material, pages 3-4.

[14] Catt, Carrie Chapman. Carrie Chapman Catt Papers: General Correspondence, Circa 1890 to 1947; Hooper, Mrs. Ben; 1927 to 1929. - 1929, 1927. Manuscript/Mixed Material, pages 18, 21, and 24.

[15] "United States Census, 1930," database with images, FamilySearch, accessed 16 January 2021, Alaska P Davidson, Mount Vemon, Fairfax, Virginia, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 18, sheet 18B, line 53, family 404, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 2442; FHL microfilm 2,342,176.

[16] "Virginia, Death Certificates, 1912-1987," database with images, FamilySearch, 16 August 2019), Alaska Packard Davidson, 16 Jul 1934; from "Virginia, Marriage Records, 1700-1850," database and images, Ancestry, 2012; citing Alexandria, , Virginia, United States, entry #15826, Virginia Department of Health, Richmond.

Note: This was originally posted on Jan. 21, 2021 on the main Packed with Packards WordPress blog (it can also be found on the Wayback Machine here). My research is still ongoing, so some conclusions in this piece may change in the future.

© 2021-2022 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#fbi#fuck the fbi#alaska packard#alaska packard davidson#20th century#doj#j. edgar hoover#ohio#warren packard#william doud packard#james ward packard#packard car company#packards#packard#marriage#tuberculosis#pennsylvania#mount vernon#chautauqua#viriginia#surveillance#lesbians#dar#lgbtq

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

May 1945.

President Truman wrote in his diary:

“FBI is ... dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail… This must stop.”

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

J. Edgar Hoover is proof white gays been full of shit

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

The America we don't speak of

#Synarchy#Nazi#oligarchy#assassinations#Otto Skorzeny#Roy Cohn#Dulles brothers#Dallas#military#CIA#Murder Inc.#JFK#RFK#ratlines#FBI#J. Edgar Hoover

0 notes

Text

'The movie "Oppenheimer" is less about the bomb and more about the trials — both moral and political — that beset J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer was the World War II physicist who spearheaded America's race to beat the Nazis before they could invent an atomic bomb.

But to the extent that this is a war story, it’s about the Cold War and the anti-Communist fever that tore through the U.S. even before Germany and Japan surrendered. The movie doesn’t begin with the development of the bomb at a top secret lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico, but in 1954, with Oppenheimer defending his American loyalty before a hostile panel in a cramped Washington, D.C., conference room.

The film shifts back and forth from that conference room to scenes of Oppenheimer’s guiding role in the development of the bomb to a 1959 Senate hearing that reveals the darker forces of Washington. Scriptwriter and director Christopher Nolan drew heavily on the historical record, and in all important ways, he hewed to the facts.

But he did invent a few things, and he simplified others, for the sake of crafting a gripping tale. Fair warning: As we compare what’s in the film with what really happened, we spoil a few surprises.

In the movie: Oppenheimer has a couple of conversations with Albert Einstein about the possibility of the bomb igniting the atmosphere and about the consequences of building it.

In reality: The issues were real, but the conversations are invented.

In one scene, physicist Edward Teller flags the possibility that the bomb will set off a chain reaction that would ignite the atmosphere. Oppenheimer asks Einstein to check it out. That discussion never happened. Oppenheimer did consult a fellow physicist, Arthur Compton.

Nolan acknowledged this in an interview with The New York Times, saying he brought in Einstein, because he was "the personality people know in the audience."

The film accurately shows Los Alamos physicist Hans Bethe run the numbers and declare that the scenario couldn’t happen.

The other invented scene with Einstein comes at the very end. The two men stand by a still pond on the grounds of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. It is set in 1947, when Oppenheimer became institute director, joining Einstein, who had been there for many years.

The conversation is fictional, but the two worked together, and the script tracks with the views they held.

In 1947, Oppenheimer was still riding high, celebrated as the father of the atomic bomb. In the film, Einstein warns Oppenheimer of fame’s fickleness.

"It’s your turn to deal with the consequences of your achievement," Einstein says. "And one day, when they have punished you enough, they’ll … give you a medal. And tell you that all is forgiven."

Einstein had no use for politicians. In 1951, during the years of McCarthyism and anti-Communism run amok, Einstein wrote to an acquaintance, "People acquiesce without resistance and align themselves with the forces of evil."

At the end of the scene by the pond, Oppenheimer recalls the worry before the first test that "we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world." Einstein nods, and Oppenheimer adds, "I believe we did."

Both men feared the power that had been unleashed. Oppenheimer pressed President Dwight D. Eisenhower to minimize the threat of a nuclear arms race and to set the American public straight on atomic weapons’ immense destructive capacity. Einstein was a pacifist who championed nuclear disarmament.

In the movie: Los Alamos is said only to contain a boys’ school and to serve as a site for burial rites for local Indians.

In reality: Homesteaders and owners of two properties were driven away from the land, with unequal compensation.

In the film, Oppenheimer expressed a desire to combine physics and New Mexico, and he found a way to do so when it was time to select a location for the central laboratory code-named Project Y. In real life, he had a ranch in Albuquerque and suggested New Mexico as an option, deeming the Sangre de Cristo mountains remote enough for a secret town. Manhattan Project Director Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves chose Los Alamos, which is about 35 miles from Santa Fe, New Mexico.

While inspecting the site in the film, Oppenheimer said Los Alamos had a boys’ school to commandeer and that the local Native Americans come for burial rites, but "after that, nothing." After Groves made the decision to "build the town," Oppenheimer projected the site would open in two months.

This is a simplification. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, most of the 50,000 acres used for the Manhattan Project already belonged to the government, but about 8,900 acres were privately owned. There were two dozen homesteaders and two larger properties — the Los Alamos Ranch School and the Anchor Ranch.

The Los Alamos Ranch School, started in 1917, trained young men through "rigorous outdoor living and classical education." On Dec. 7, 1942, the school’s director received a letter from U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson that said the U.S. Army was taking over the school’s property. Early arrivals to Los Alamos resided in the school’s buildings.

The owners of both properties negotiated sale prices — the school got paid $225 per acre, while the Anchor Ranch was paid $43 per acre. However, the Hispanic homesteaders were paid only $7 an acre, and their heirs later sought reparations. Some landowners did not receive their payments.

Many Hispano — Mexican or Spanish descendants in northern New Mexico — and Native workers returned to Los Alamos to work for the Manhattan Project.

In the movie: U.S. War Secretary Henry Stimson removed Kyoto from the list of possible Japanese targets because he honeymooned there.

In reality: Even though he visited twice, there is no conclusive evidence that Stimson spent his honeymoon in Kyoto.

James Remar, who portrayed Stimson, improvised the dialogue in which Stimson removes Kyoto from the list of targets because that’s where he had his honeymoon.

According to The New York Times’ interview with Nolan, actors came into the shoot with their own research, allowing them to "improvise" the discussion. When Remar mentioned that Stimson and his wife honeymooned in Kyoto, Nolan told him, "Just add that."

Although Stimson went to great lengths to keep Kyoto from being targeted, records don’t support the claim that he honeymooned there. According to historian Alex Wellerstein, none of the serious, scholarly accounts about the Kyoto incident or Stimson’s writings mentioned that he spent his honeymoon in Kyoto. Wellerstein noted that Stimson and his wife visited Kyoto in 1926, more than 30 years after their wedding. He also visited Kyoto for one night in 1929.

In the movie: Lewis Strauss’ role in orchestrating the attack on Oppenheimer plays a pivotal role in sinking Strauss’ Cabinet confirmation.

In reality: There were several reasons the long knives were out for Strauss, and the Oppenheimer affair was just one of them.

In 1959, Lewis Strauss, a staunch Republican, faced a Democratic majority in his Senate confirmation hearing to be commerce secretary. Watching the movie, you could be forgiven for thinking the Oppenheimer affair was the only hurdle Strauss faced. It was more than that.

The opening attack on Strauss came from Sen. Estes Kefauver, D-Tenn. Kefauver focused not on Oppenheimer, but on a 1955 botched power plant contract that took place on Strauss’ watch as head of the Atomic Energy Commission and that cost the government $1.8 million to settle legal claims.

Sen. Clinton Anderson, D-N.M., accused Strauss of hiding key information on nuclear policies from the Senate. Sen. Eugene McCarthy, D-Minn., said a vote for Strauss amounted to "approval of the unwarranted extension of executive secrecy."

In the final vote, two Republicans joined 47 Democrats to scuttle Strauss’ confirmation.

This leads to one other embellishment in the movie.

An aide tells Strauss there were three holdouts, "led by the junior senator from Massachusetts, young guy, trying to make a name for himself … John F. Kennedy."

Nolan takes poetic license with the politics. The vote margin is correct, but Strauss’ bid cratered thanks to the two Republicans. If they had voted his way, he would have prevailed. And every Democrat who was angling to be president, including Lyndon B. Johnson, Hubert Humphrey and Stuart Symington, voted against Strauss.

In the movie: Strauss masterminds the move to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance, a loss that would cut Oppenheimer out of any policy role.

In reality: Strauss did muscle Oppenheimer out, and his machinations had surprising repercussions today.

A solid paper trail ties Strauss to the attack on Oppenheimer.

"American Prometheus" pinpoints the day that Strauss launched his campaign to topple Oppenheimer: May 25, 1953. That day, Strauss told Eisenhower that Oppenheimer’s communist sympathies were not to be trusted.

Strauss put the wheels in motion to unseat Oppenheimer even earlier. In April 1953, he met with William Borden. Borden ultimately wrote a letter to the FBI that said, "More probably than not, J. Robert Oppenheimer is an agent of the Soviet Union." That letter started Oppenheimer’s downfall.

Soon after his April meeting with Strauss, Borden signed out Oppenheimer’s security file from the Atomic Energy Commission’s secure document vault. Borden was a top congressional staffer on atomic policy and had the proper clearance, but even though he left his job at the end of May, he kept the file until Aug. 18. By then, Strauss was fully installed as the commission’s chair.

After Borden returned the file, Strauss immediately signed it out and didn’t return it to the commission’s security vault until Nov. 4. Three days later, Borden sent his letter to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover that called Oppenheimer a Soviet agent.

Harold Green, counsel to the commission’s security division at the time, wrote that people in the division told him that Strauss had promised Hoover that he would get Oppenheimer out of the way.

The proof of Strauss’ fingerprints on the purge of Oppenheimer grows from there. Strauss handpicked the panel that would prosecute Oppenheimer and set the ground rules that blindsided Oppenheimer’s lawyers. He had access to the FBI’s wiretaps on calls between Oppenheimer and his lawyers.

The hearing itself was as grueling as the movie presents.

Anti-communist fervor’s full force was trained on Oppenheimer, and little artistic embellishment was needed; in 2014, the U.S. Energy Department released the entire transcript, giving the filmmakers ample material to include in the script verbatim.

Despite finding "no evidence of disloyalty," the panel and then later the full Atomic Energy Commission voted to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance, and from then on, he was cut off from the government’s official nuclear policy discussions. He remained head of the institute in Princeton and became a sought-after speaker, writing and lecturing on science’s role in the nuclear age.

Epilogue: The 2022 restoration

There’s not much you can do for someone who’s been dead for more than half a century, but on Dec. 16, 2022, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm vacated the Atomic Energy Commission’s 1954 decision. Oppenheimer’s colleagues had been asking for that for decades, starting immediately after the commission ruled against him.

Indirectly, the Oppenheimer film helped reverse the black mark on his reputation.

In March 2022, filming was underway at Los Alamos. Kai Bird, one of the authors of "American Prometheus," was invited to visit the set and have dinner with Los Alamos National Laboratory Director Thom Mason. As the two spoke, Bird made a simple point about Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing.

"What was done to him was unfair and a complete abuse of the kind of legal authorities under which (security) clearances operate," Mason told PolitiFact.

Seen this way, someone didn’t need to challenge the panel’s findings; what was wrong was the deeply flawed process. Mason took that point to eight previous lab directors, and on April 5, 2022, they sent a letter to Granholm asking her to reverse the commission’s decision.

In August 2022, 43 U.S. senators made a similar request. It was mostly Democrats who signed on, but four Republicans did too, including Sens. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., Marco Rubio, R-Fla., James Inhofe, R-Okla., and Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska.

The push had everything to do with how the deck was stacked against Oppenheimer. This was hardly news. A 1959 internal Atomic Energy Commission review found that "the system failed . . .[(and) that a substantial injustice was done to a loyal American."'

#Oppenheimer#Christopher Nolan#Albert Einstein#Lewis Strauss#Arthur Compton#Edward Teller#Kai Bird#Los Alamos#Atomic Energy Commission#Thom Mason#Jennifer Granholm#American Prometheus#Harold Green#J. Edgar Hoover#William Borden#Eisenhower#James Remar#Henry Stimson#Leslie Groves#The Manhattan Project#Institute for Advanced Study#Princeton

0 notes